Sir,

The current pandemic situation on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is expanding since its first report on December 2019. To date, 14,667,659 people are infected from SARS-CoV-2 all over the world, and India has reported on July 20, 2020, a total of 1,119,412 SARS-CoV-2 cases1,2. SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded, positive-sense, poly-A-tailed RNA belonging to the family Coronaviridae. Its genome size ranges from 27 to 34 kb, which encodes for non-structural proteins, structural proteins and accessory proteins3. To limit the spread of the virus, guidelines related to preventive measures are published by the World Health Organization as well as the Indian government4,5 as no vaccines or drugs are currently available. Processes for the identification of suitable antiviral drugs and vaccines have been initiated. Vaccine peptides based on the B-cell and T-cell epitope-inactivated6 and attenuated virus vaccines7, subunit vaccine, DNA vaccines and mRNA vaccine8 are some of the approaches that are used for the design of the vaccine candidates for COVID-19. These approaches are implied based on the dominant population of the viral sequences present within the host cells. However, the viral RNA in the host cells is a heterogeneous population depending on the rate of mutations and their adaptation. The dominant population of the virus can be affected by the random mutations, a bottleneck event or changes that destabilize the present equlibrium9.

The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene of the coronaviruses is known to be errorprone, thereby leading to frequent mutation and recombination10. The presence of quasispecies has been reported earlier from both SARS-CoV-111 and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)12. Quasispecies analysis by Xu et al11 from nine individual patient samples infected with SARS-CoV-1 revealed nine recurrent variant sites in a total of 107 variations. Park et al12 studied 35 samples of 24 patients and identified a total of 16 nucleotide variant positions in MERS-CoV. Recently, Capobianchi et al13 analyzed quasispecies in two SARS-CoV-2 patients in Italy. They could identify two nucleotide variations in ORF 1ab gene at positions 2269 and 7388 having AàT and GàA substitutions, respectively. The present study was aimed to look upon the quasispecies in the different SARS-CoV-2 clinical samples sequenced and the consensus sequences for which were discussed in our previous studies14,15,16.

The study was conducted in the ICMR-National Institute of Virology, Pune, India, during March to April 2020 after obtaining prior approval from the Instructional Ethics Committee. The next-generation sequencing data from Italian tourists, contacts of the Italian tourists and the Indian citizens sampled at Iran were used to analyze the quasispecies present within the clinical samples (nasal/throat swab). The samples were analyzed by using the variant detection tool as implemented in the QIAGEN CLC genomics workbench 20.017 (QIAGEN, Aarhus, Denmark). The reference sequence used for deriving variants from the sequenced reads was the SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan HU-1 strain (accession number: NC_045512).

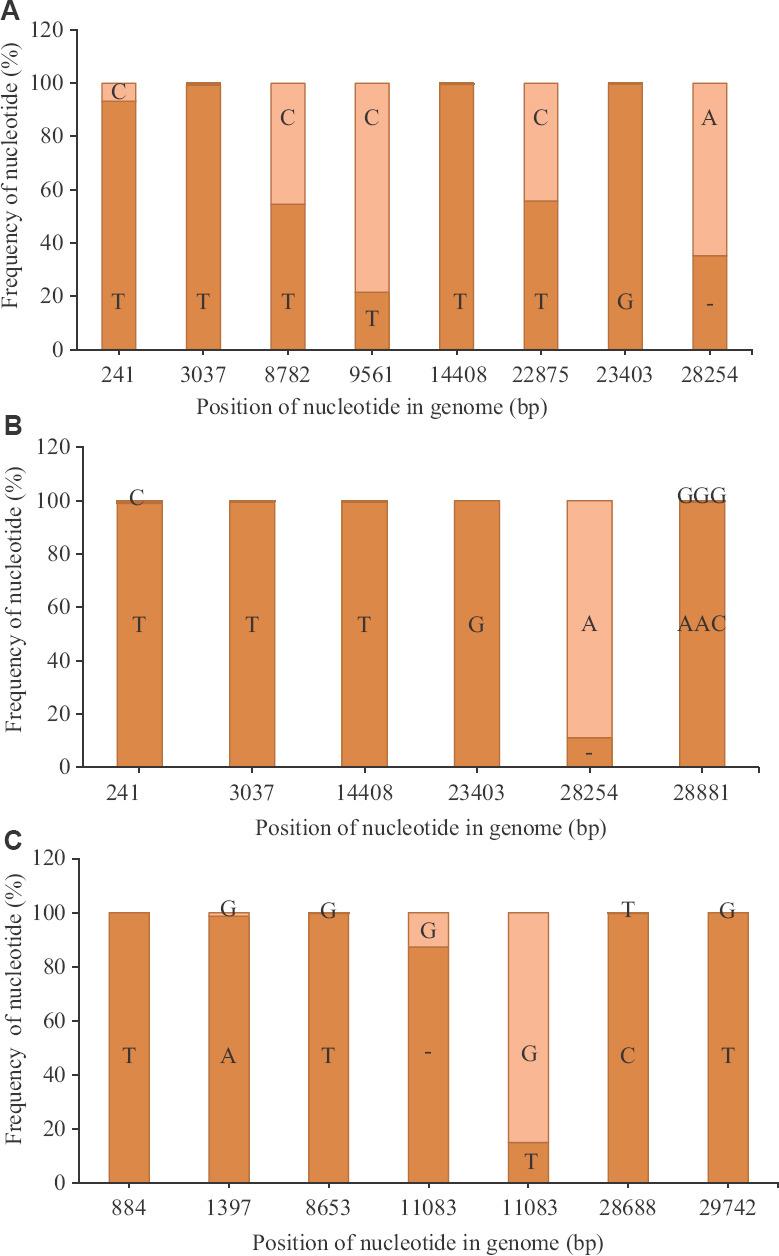

Two different types of SARS-CoV-2 strains are classified depending on the nucleotide present at genomic position (GP) 8782 (gene: ORF1ab) and 28144 (gene: ORF8)18. The nucleotide change in the GP 8782 is a synonymous nucleotide substitution, whereas the GP 28144 has a non-synonymous nucleotide substitution, where Leu is observed when the nucleotide is T and Ser when it is C. The strain is classified as S-type when the nucleotides are T and C at GPs 8782 and 28144, respectively and is considered to be non-virulent. However, when the nucleotides are C and T at those positions, respectively, it is classified as L-type, considered to be virulent in nature18. However, there is no experimental evidence to support the method of classification. The reads of the clinical samples from the Italian tourists demonstrated that the GP 8782, on an average, had 54.6 per cent of T nucleotides in 50 per cent of the dataset analyzed (n=8) and the rest as C (Figure A). In contrast, GP 28144 had T for all the sample sets analyzed. The presence of TT nucleotides at the GP 8782 and 28144, respectively, in 50 per cent of the Italian samples was observed at the quasispecies level. Quasispecies was also observed in 50 per cent of the dataset analyzed (n=8), at GP 9561 and 22875, which led to non-synonymous change at the amino acid level (SeràLeu and SeràPhe, respectively) that had CàT nucleotide change for both positions.

Figure.

Nucleotide variation in SARS-CoV-2 reads: (A) Average percentage of nucleotide variation at different genomic position observed for more than 50 per cent of the sample set, with respect to the SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan HU-1 strain (accession number: NC_045512) for the reads retrieved from the Italian tourists (n=8); (B) their contacts in India (n=7); and (C) the Indian national sampled at Iran (n=11). The dark orange colour depicts the average frequency of the reads that mapped to the sequences in study, whereas the light orange colour depicts the average frequency for the reference allele.

The Indian contacts of the Italian tourists, however, had a different profile wherein the quasispecies observed in the Italian tourists were not observed for all the sample sets analyzed (n=7) (Figure B). The dominant nucleotide changes were reflected in the consensus sequences for the retrieved genome. For example,

GP 241 (5'UTR) had T nucleotide (99.1%) compared to the Italian tourists (93%). The nucleotide deletion at the GP 28254 (ORF8 gene) was reduced by an average of 24 per cent when compared to the Italian tourists. The third sample set was from the Indian citizens sampled in Iran (Figure C), which showed quasispecies in more than 50 per cent of this sample set. This set had a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) deletion in the ORF1ab gene (GP: 11083), with an average of 87.3 per cent, leading to early termination of the ORF1 ab polypeptide (Figure C). The ORF1ab proteins in these cases was encoded by the remaining 12.7 per cent of the intact gene, which is present in minority. The remaining SNPs deletions observed in this set had an average above 98.7 per cent, indicating a lesser variation of the quasispecies population of the analyzed set (n=11). Variant analysis of a few isolates of the clinical specimens was also made, and it was observed that the nucleotide variation was similar to that of the respective clinical specimens (data not shown).

The quasispecies identified by Capobianchi et al13 were different from those observed in our study. The quasispecies present in the three sets of the clinical samples analyzed revealed the presence of variation in the nucleotide positions and virus evolution to adapt towards the new host. This study also indicates that a quasispecies may vary depending on the location and indicates the further exploration of more massive dataset to identify variability among different clinical samples. Hence, it is vital to consider the heterogeneous virus population present within the host, when designing antiviral stratergies19. RNA viruses are known to have a higher mutation rate compared to their hosts20, which leads to quasispecies formation in them. A higher mutation rate provides the virus an opportunity to expand its quasispecies population to adapt either to the same host or to the others under the influence of selection/environmental pressure and generate into different clades. However, the other mechanisms, such as random mutations, changes due to RNA editing or error in proofreading mechanisms that can lead to changes in the nucleotides cannot be neglected. Such changes increase the likelihood of generating an escape mutant21,22, which may be predominately influenced by selection/environmental pressure.

In brief, this study points towards the variations observed in the SARS-CoV-2 quasispecies sampled from different locations and indicates the need of analyzing a larger set of population from varied locations, which is also the limitation of this study.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the technical support given by Ms Pranita Gawande, Servshri Yash Joshi, Annasaheb, Hitesh Dighe and Shrimati Ashwini Waghmare.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: Financial support was provided by the Department of Health and Research, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Reports. [accessed on April 7, 2020]. Available from: https://wwwwhoint/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports .

- 2.Worldometer. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic - Coronavirus cases: 14,667,659; Deaths: 609,508. [accessed on July 20, 2020]. Available from: https://wwwworldometersinfo/coronavirus/

- 3.Chan JF, Kok KH, Zhu Z, Chu H, To KK, Yuan S, et al. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:221–36. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1719902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. [accessed on May 20, 2020]. Available from: https://wwwwhoint/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public .

- 5.MyGov. IndiaFightsCorona COVID-19. [accessed on May 20, 2020]. Available from: https://mygovin/covid-19/

- 6.Feng Y, Qiu M, Zou S, Li Y, Luo K, Chen R, et al. Multi-epitope vaccine design using an immunoinformatics approach for 2019 novel coronavirus in China (SARS-CoV-2) bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 101101/20200303962332. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shang W, Yang Y, Rao Y, Rao X. The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia calls for viral vaccines. NPJ Vaccines. 2020;5:18. doi: 10.1038/s41541-020-0170-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodgson J. The pandemic pipeline. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:523–32. doi: 10.1038/d41587-020-00005-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domingo E, Sheldon J, Perales C. Viral quasispecies evolution. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76:159–216. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05023-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of 2019-nCoV - A quick overview and comparison with other emerging viruses. Microbes Infect. 2020;22:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu D, Zhang Z, Wang FS. SARS-associated coronavirus quasispecies in individual patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1366–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc032421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park D, Huh HJ, Kim YJ, Son DS, Jeon HJ, Im EH, et al. Analysis of intrapatient heterogeneity uncovers the microevolution of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2016;2:a001214. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a001214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capobianchi MR, Rueca M, Messina F, Giombini E, Carletti F, Colavita F, et al. Molecular characterization of SARS-CoV-2 from the first case of COVID-19 in Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:954–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yadav PD, Potdar VA, Choudhary ML, Nyayanit DA, Agrawal M, Jadhav SM, et al. Full-genome sequences of the first two SARS-CoV-2 viruses from India. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:200–9. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_663_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkale P, Patil S, Yadav PD, Nyayanit DA, Sapkal G, Baradkar S, et al. First isolation of SARS-CoV-2 from clinical samples in India. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:244–50. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1029_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potdar V, Cherian SS, Deshpande GR, Ullas PT, Yadav PD, Choudhary ML, et al. Genomic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 strains among Indians returning from Italy, Iran & China, & Italian tourists in India. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:255–60. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1058_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CLC Genomics Workbench 20.0 (QIAGEN) [accessed on April 7, 2020]. Available from: http://resources.qiagenbioinformatics.com/manuals/clcgenomicsworkbench/current/index.php?manual=Introduction_CLC_Genomics_Workbench.html .

- 18.Tang X, Wu C, Li X, Song Y, Yao X, Wu X, et al. On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Natl Sci Rev. 2020;7:1012–23. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domingo E, Baranowski E, Ruiz-Jarabo CM, Martín-Hernández AM, Sáiz JC, Escarmís C. Quasispecies structure and persistence of RNA viruses. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:521–7. doi: 10.3201/eid0404.980402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffy S. Why are RNA virus mutation rates so damn high? PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e3000003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novella IS, Domingo E, Holland JJ. Rapid viral quasispecies evolution: Implications for vaccine and drug strategies. Mol Med Today. 1995;1:248–53. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(95)91551-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Presloid JB, Novella IS. RNA viruses and RNAi: Quasispecies implications for viral escape. Viruses. 2015;7:3226–40. doi: 10.3390/v7062768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]