Patient presentation: A 52 year-old male construction worker with no medical history presented to the emergency department with one week of fatigue and two days of intermittent substernal chest pain and dyspnea that began at work. On the day of presentation, he had profound generalized weakness and orthopnea. He emigrated from Mexico years earlier and reported drinking 1–3 beers/day. He did not take medications, vitamins or supplements. He had an unremarkable social and family history, and review of systems.

Dr Durstenfeld: This patient presented with subacute fatigue, chest pain and dyspnea concerning for new onset heart failure with exertional symptoms that could be myocardial ischemia from an acute plaque rupture or demand ischemia. The initial differential diagnosis is broad, and the first step is to consider emergencies such as ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), aortic dissection, pericardial tamponade, arrhythmias, and pulmonary embolism.

Patient presentation (continued): Upon arrival to the emergency room, he was hypotensive (85/52 mm Hg), tachycardic (118/min), and tachypneic (28/min) with normal mental status, elevated jugular venous pulsation, normal heart sounds without murmurs or gallops, crackles 3/4 up the lung fields, and warm extremities without edema. His pulses were bounding throughout, blood pressures were symmetric in all four extremities, and neurologic exam was normal.

Abnormal initial laboratory tests included a leukocyte count of 25 ×109 cells/mL, creatinine 2.5 mg/dL, troponin 7.4 ug/mL, anion gap of 29 with lactate of 11 mmol/L, and b-type natriuretic peptide 1924 pg/mL; D-dimer was within normal limits. Electrocardiogram had sinus tachycardia, mild PR segment depression, and T-wave inversions inferiorly. Chest radiograph confirmed multifocal infiltrates consistent with pulmonary edema.

Dr Durstenfeld: His physical exam had evidence of left-sided heart failure, and the most surprising features were warm extremities and bounding pulses throughout; laboratory evidence suggested profound hypoperfusion. After ruling out STEMI, the differential diagnosis for acute heart failure and presumed cardiogenic shock starts with non-STEMI, possibly with mitral regurgitation causing pulmonary edema. As our hospital serves a diverse patient population in San Francisco where endocarditis is not uncommon, aortic regurgitation due to endocarditis also fit despite the lack of obvious risk factors. The murmur may not be evident in acute severe aortic regurgitation with high filling pressures. Cardiomyopathy does not usually present with high cardiac output, but acute myopericarditis with a systemic inflammatory response could explain heart failure and vasodilation resulting in lower vascular resistance and therefore higher cardiac output than expected. We also considered sepsis with a septic cardiomyopathy with pneumonia as a source. Finally, we thought of thyrotoxicosis and other causes of high output failure. To refine the differential diagnosis, the next steps include echocardiography and left and right heart catheterization.

Patient presentation (continued): Echocardiogram demonstrated mildly reduced left ventricular function with an ejection fraction of 40–45% and inferolateral hypokinesis, normal right ventricular function, high cardiac output, elevated pulmonary pressures, and no significant valve disease. After endotracheal intubation, he was taken emergently to the cardiac catheterization laboratory which revealed mild nonobstructive coronary artery disease. Right heart catheterization demonstrated elevated right atrial pressure of 16 mm Hg, post-capillary pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary artery pressure of 35 mm Hg), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 22 mm Hg, pulmonary vascular resistance 1.1 Woods Units, high cardiac output of 12 L/min by thermodilution (index 6.2 L/min/m2) and 23 L/min by Fick (index 11 L/min/m2), low systemic vascular resistance (327 dynes sec cm−5), a pulmonary artery oxygen saturation of 84%, and no left-to-right shunt by oximetry.

Dr Durstenfeld: High output heart failure is defined as signs or symptoms of heart failure with a cardiac index of ≥4 L/min/m2 and elevated filling pressures or pulmonary hypertension. We considered common etiologies in the differential diagnosis (1). He was not anemic or obese. His thyroid function and liver function (including prothrombin time and platelets) were normal. He did not have evidence of lung disease, myeloproliferative syndrome, or Paget’s disease. The cardiac catheterization did not reveal an intracardiac left-to-right shunt, and he did not have an arteriovenous fistula. The leading diagnosis initially was septic shock of unknown source, so he was treated empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Myopericarditis was also considered due to his electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, and coronary angiogram, but did not explain his high cardiac output.

Patient presentation (continued): The patient was admitted to the Cardiac Care Unit for management of vasodilatory shock and high output heart failure. He was treated empirically for presumed septic shock with septic cardiomyopathy without improvement. He remained mechanically ventilated requiring minimal support. Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) was initiated for anuric renal failure and elevated filling pressures. He developed anisocoria, cranial nerve VI palsy, and cranial nerve III paresis without imaging evidence of acute stroke. A pulmonary artery catheter was placed 24 hours after admission to tailor his therapy. Despite maximal doses of norepinephrine, epinephrine, vasopressin, and phenylephrine, he remained in vasoplegic shock with high filling pressures. His cardiac output and blood pressure decreased and lactate increased. Paralysis, steroids, calcium chloride, hydroxocobalamin, ascorbic acid, and methylene blue had no effect on his hemodynamics. As his cardiac index decreased below 2.2 L/min/m2, dobutamine was cautiously added with close monitoring. Mechanical circulatory support was considered by a multidisciplinary team but thought to be not helpful in vasodilatory shock. By 36 hours, blood cultures remained no growth and pan-CT imaging revealed no source of infection or extracardiac shunt.

Dr Durstenfeld: In summary, this previously healthy man presented with acute high output heart failure, vasodilatory shock, and persistent lactic acidosis. When he did not respond to vasopressors and antibiotics we considered more unusual causes of vasodilatory shock and high output heart failure. Beriberi can present in an acute fulminant form called Shoshin beriberi. Although he had no specific risk factors with only moderate alcohol intake by history, we administered thiamine.

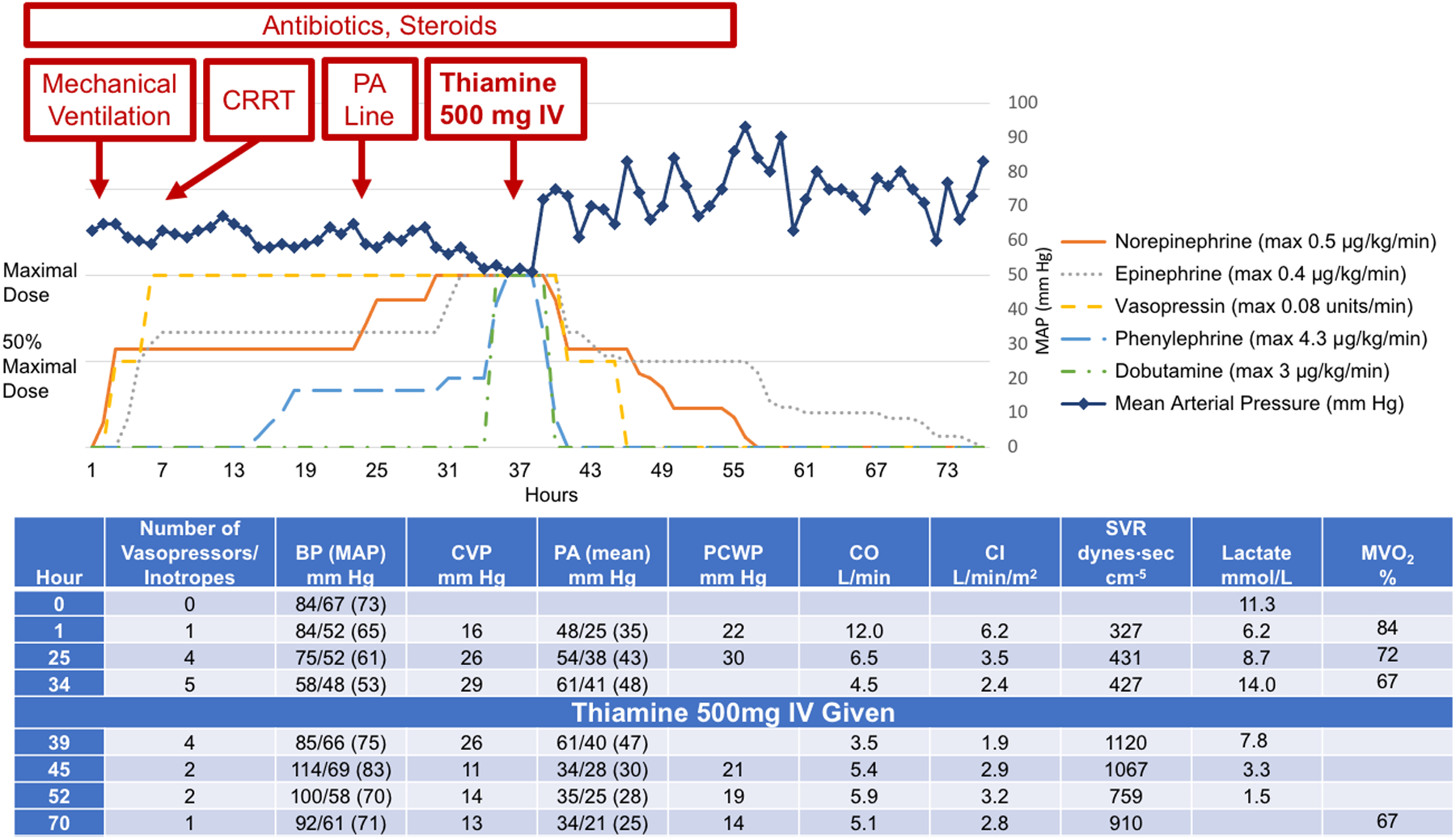

Patient presentation (continued): Thiamine 500mg was administered intravenously. His blood pressure increased dramatically within minutes (Figure 1). His systemic vascular resistance and cardiac index increased, and his lactate decreased. CRRT was restarted and uptitrated to remove fluid. Vasopressors were weaned off within 36 hours. His cranial nerve abnormalities resolved, he was extubated and weaned off CRRT. He was continued on intravenous thiamine 500mg every 8 hours for three days. Blood thiamine levels and red blood cell transketolase activity were ordered from the hospital laboratory but were not performed prior to thiamine administration.

Figure 1. Hemodynamics and vasopressors before and after thiamine administration.

The patient’s blood pressure worsened requiring escalating doses of vasopressors. Within two hours of administration of thiamine, the blood pressure increased, and vasopressors were started to be weaned off. The cardiac output improved, and the lactic acidosis resolved. 36 hours after thiamine initiation, the patient was weaned off all vasopressors. CRRT indicates continuous renal replacement therapy; BP, blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; CVP, central venous pressure; PA, pulmonary artery; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; CO, cardiac output; CI, cardiac index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; MVO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation.

Dr Durstenfeld: The key to diagnosis of beriberi is to have a high index of suspicion, particularly in patients with risk factors, as laboratory testing has poor test characteristics. Recovery within minutes to hours after administration of intravenous thiamine is considered diagnostic. There is little downside to empiric thiamine administration as allergic reactions and adverse effects are very rare.

Patient presentation (continued): During recovery, he developed neuropathic pain in all four extremities, intermittent vertical nystagmus, and delirium. Cardiac MRI performed ten days after he presented showed normal biventricular function with no delayed gadolinium enhancement, and brain MRI revealed punctate enhancement of the left mammary body consistent with thiamine deficiency (Figure 2). He ultimately reported eating less food and drinking more beer in the preceding months due to irregular employment. His hospital course was complicated by an upper gastrointestinal bleed attributed to a stress ulcer, and duodenal biopsy did not reveal a pathologic explanation for poor absorption of dietary thiamine. He was started on lisinopril and metoprolol and transitioned from intravenous to oral thiamine 300mg TID. Repeat echocardiogram one month after discharge was normal. After prolonged rehabilitation due to his neuropathy, likely due to thiamine deficiency with a contribution of critical-illness neuropathy, he is no longer able to work in construction but otherwise made a remarkable recovery.

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the heart and brain after recovery.

Cardiac MRI demonstrated normal cardiac size and function without delayed gadolinium enhancement (left). Brain MRI (right) demonstrated punctate enhancement of the left mammillary body, indicated by the arrow, consistent with thiamine deficiency.

Dr Durstenfeld: His dramatic recovery with treatment is consistent with reports of Shoshin beriberi (2). His development of neurologic symptoms corroborated with brain MRI imaging consistent with Wernicke encephalopathy confirms a unifying diagnosis of thiamine deficiency. This patient lacked the degree of malnutrition or alcohol abuse typically implicated in beriberi, but perhaps his alcohol intake was more than reported, and he may have confabulated about his alcohol intake and the time course of symptoms.

Discussion

Thiamine (vitamin B1) is an important cofactor in aerobic metabolism in the Krebs cycle and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway, and its deficiency causes beriberi. First described in ancient China, beriberi became epidemic in 19th century East Asia as milling white rice removes thiamine from the outer husk. By randomizing ships to rice alone versus a varied diet, Takaki Kanehiro studied and eliminated the disease in the Japanese navy in 1885. Christaan Eijkman shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1929 for discovering thiamine deficiency caused beriberi.

The global incidence of thiamine deficiency is unknown, but up to 30% of patients with heart failure and sepsis are thiamine deficient, and dietary thiamine deficiency remains prevalent in Southeast Asia (3). Risk factors include severe malnutrition, chronic alcoholism, incarceration, refugee status, social isolation, bariatric surgery, and loop diuretics. Testing for thiamine deficiency remains challenging; blood thiamine levels do not reflect total body stores and are low in acute illness. The erythrocyte transketolase activity or thiamine pyrophosphate effect tests have poor sensitivity, specificity, and require special specimen processing. The gold standard, high performance liquid chromatography, is expensive and rarely available clinically.

Adults with thiamine deficiency may present with neurologic symptoms, called “dry beriberi” with either peripheral neuropathy or Wernicke encephalopathy, or cardiac symptoms called “wet beriberi” with high-output heart failure or hemodynamic collapse and multiorgan failure (Shoshin beriberi). Published in 1945, Marion Blankenhorn’s diagnostic criteria of beriberi heart disease remain relevant and include the following: enlarged heart with normal rhythm, dependent edema, elevated venous pressure, peripheral neuritis or pellagra, nonspecific alterations in the electrocardiogram, no other evident cause for heart disease, thiamine deficiency for three months, and improvement of symptoms and reduction of heart size after thiamine replacement (4). In 1960, Paul Wolf and Murray Levin reported two cases of Shoshin beriberi in the New England Journal of Medicine: one diagnosed on autopsy and the other recovered an hour after intravenous thiamine (5). Autopsy findings include myocardial edema, central necrosis of muscle fibers, and mitochondrial lesions. Patients with Shoshin beriberi typically recover within minutes to hours after administration of thiamine, and the dramatic response is considered diagnostic given the limitations in thiamine testing.

In beriberi, thiamine deficiency blocks the Krebs cycle, shifting from aerobic to anerobic metabolism with buildup of lactate and pyruvate (2) (Figure 3). This results in an increase in adenosine monophosphate, which is released as adenosine in skeletal muscle resulting in vasodilation and low vascular resistance via shunt physiology. Arterial underfilling leads to decreased renal perfusion resulting in renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation and plasma volume expansion. Lactic acidosis and increased tissue demand for oxygen increases cardiac output, and the heart shifts metabolism to free fatty acids, bypassing the Krebs cycle. At the same time, mitochondria cannot utilize oxygen delivered, leading to reduced oxygen extraction, high venous saturations and overestimation of Fick cardiac output, which explains the discrepancy between the thermodilution and Fick cardiac outputs in this case.

Figure 3. Pathophysiology of high output heart failure and vasodilatory shock in Shoshin Beriberi.

Beriberi blocks the Krebs cycle since thiamine is an essential co-factor for the Krebs cycle. This results in shift to anaerobic metabolism, lactic acidosis, and adenosine release in skeletal muscle resulting in vasodilation and a low systemic vascular resistance. There is a compensatory activation of the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system. Together this pathophysiology results in high output heart failure. There is a downward spiral of low perfusion pressure leading to escalation of vasopressors which deplete acetyl-CoA resulting in a loss of vasopressor response, ultimately resulting in vasodilatory shock. ATP indicates adenosine triphosphate; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; Acetyl-CoA, acetyl coenzyme A; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; Art, arterial; Ven, venous.

How does Shoshin beriberi progress so rapidly from chronic thiamine deficiency? As in any shock, there can be a rapid downward spiral. In this case, deprivation of alcohol, a thiamine-independent source of acetyl-coA for the Krebs cycle, may have shifted this individual further to anaerobic metabolism while increasing metabolic demands from alcohol withdrawal (4). Low perfusion pressure due low arterial pressures and high venous pressures may have additionally worsened organ perfusion. Administration of vasopressors and glucose, which was noted to cause a depletion of acetyl-CoA reserves in the 1930s, may have exacerbated the metabolic derangement. Lastly, vasopressor responsiveness requires acetyl-Co-A. All of these factors collectively create a cycle of worsening hypotension and shock.

Conclusion

Although the diagnosis and treatment have not changed in 75 years, Shoshin beriberi remains underrecognized. In particular, clinicians should consider beriberi early in patients with high output heart failure, vasodilatory shock, and lactic acidosis despite resuscitation, and treat with empiric intravenous thiamine. Shoshin beriberi is easily reversible with administration of thiamine, and deadly if not diagnosed and treated promptly.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patient for his willingness to share his story, as well as the team of doctors, nurses, and ancillary support that cared for him at Zuckerberg San Francisco General.

Funding Sources

There were no sources of funding for this research. Dr Durstenfeld is supported by US National Institutes of Health grant no. 5T32HL007731-28. Dr. Hsue is supported by NIH grant 2K24AI112393-06.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Presented as a Laennec Young Clinician Award Finalist at the Scientific Sessions of the American Heart Association, Philadelphia, PA, November 16, 2019

References

- 1.Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Redfield MM, Nishimura RA and Borlaug BA. High-Output Heart Failure: A 15-Year Experience. J Am Col Cardiology. 2016;68:473–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attas M, Hanley HG, Stultz D, Jones MR, McAllister RG. Fulminant beriberi heart disease with lactic acidosis: presentation of a case with evaluation of left ventricular function and review of pathophysiologic mechanisms. Circulation. 1978;58:566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitfield KC, Bourass MW, Adamolekun B, Bergeron G, Bettendorff L, Brown KH, Cox L, Fattal-Valevski A, Fischer PR, Frank EL, Hiffler L, Hlaing LM, Jefferds ME, Kapner H, Kounnavong S, Mousavi MPS, Roth DE, Tsaloglou M, Wieringa F, Combs GF. Thiamine Deficiency Disorders: Diagnosis, Prevalence, and a Roadmap for Global Control Programs. Ann New York Acad Sci. 2018;1430:3–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blankenhorn MA. The Diagnosis of Beriberi Heart Disease. Ann Intern Med. 1945;23:398–404. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf PL and Levin MB. Shoshin Beriberi. New England J Med. 1960; 262: 1302–1306. [Google Scholar]