Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about oncofertility practice in developing countries that usually suffer from a shortage of health services, especially those related to cancer care.

Materials and Methods

To learn more about oncofertility practice in developing countries, we generated a survey to explore the barriers and opportunities associated with oncofertility practice in five developing countries from Africa and Latin America within our Oncofertility Consortium Global Partners Network. Responses from Egypt, Tunisia, Brazil, Peru, and Panama were collected, reviewed, and discussed.

Results

Common barriers were identified by each country, including financial barriers (lack of insurance coverage and high out-of-pocket costs for patients), lack of awareness among providers and patients, cultural and religious constraints, and lack of funding to help to support oncofertility programs.

Conclusion

Despite barriers to care, many opportunities exist to grow the field of oncofertility in these five developing countries. It is important to continue to engage stakeholders in developing countries and use powerful networks in the United States and other developed countries to aid in the acceptance of oncofertility on a global level.

INTRODUCTION

Because of advances in cancer diagnosis and treatment, the overall survival rates in most young women and men with cancer have significantly increased over the past four decades.1-3 Consequently, the topic of how to prevent the chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced gonadotoxicity and subsequent fertility loss has gained attention. Oncofertility is a new interdisciplinary field at the intersection of oncology and reproductive medicine that expands fertility options for young cancer survivors.4-8 Throughout the past decade, international guidelines were published about oncofertility practice in developed countries.9-11 However, little is known about oncofertility practice in developing countries that usually suffer from a shortage of health services, especially those related to cancer care. In this study, we investigated oncofertility practice in developing countries and explore the unique barriers and opportunities for growth and expansion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

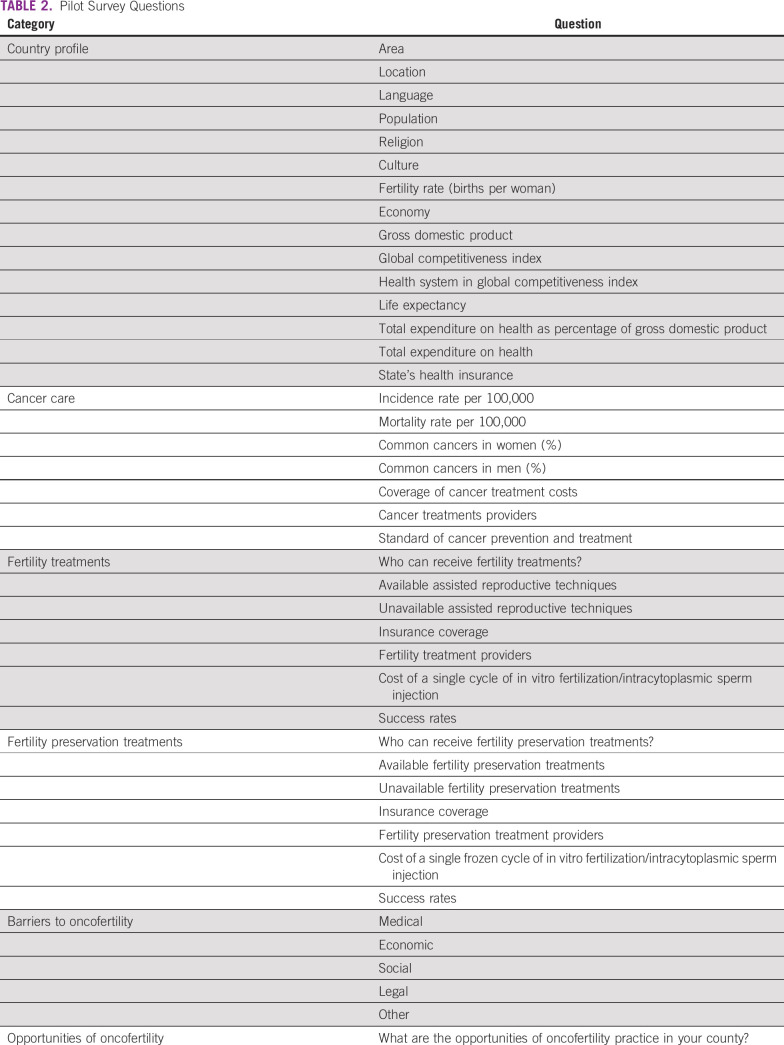

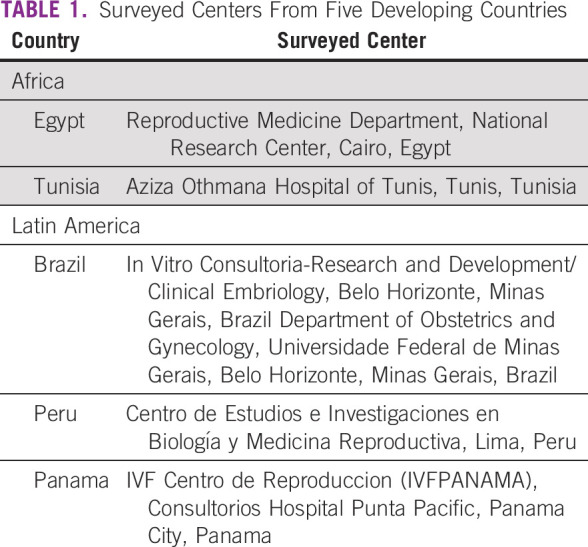

A pilot survey was generated after the panel session Resource Barriers to Oncofertility in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities at the 10th Annual Oncofertility Conference, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, November 1 to 3, 2016. To explore the various barriers and opportunities of oncofertility practice in developing countries, the survey questions were sent by e-mail to five centers from Africa and Latin America within the Oncofertility Consortium Global Partners Network (OCGPN).12 The surveyed centers from Egypt, Tunisia, Brazil, Peru, and Panama are listed in Table 1. The survey questions were grouped into six categories: country profile, cancer care, fertility treatments, fertility preservation treatments, barriers to oncofertility, and opportunities of oncofertility (Table 2). Responses from the surveyed centers were collected, reviewed, and discussed.

TABLE 1.

Surveyed Centers From Five Developing Countries

TABLE 2.

Pilot Survey Questions

RESULTS

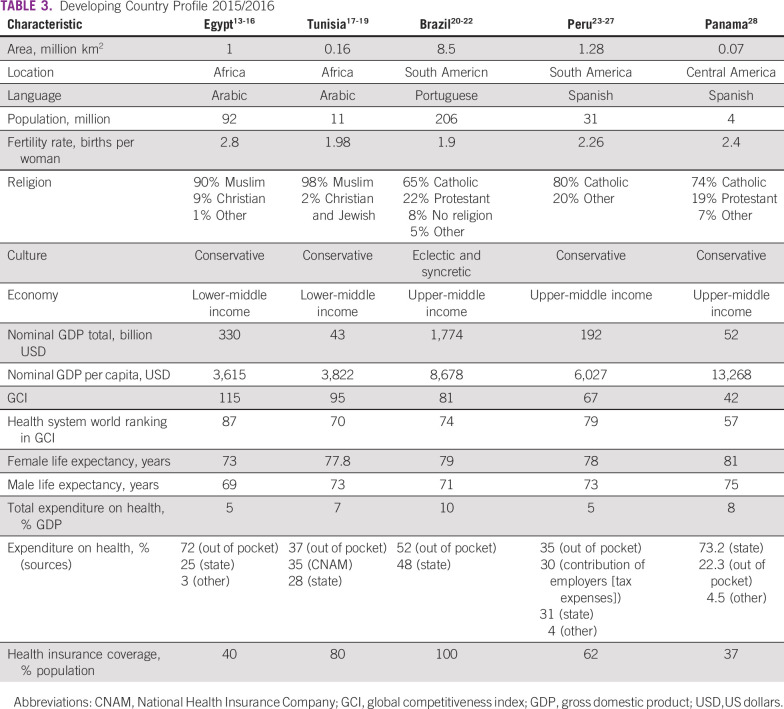

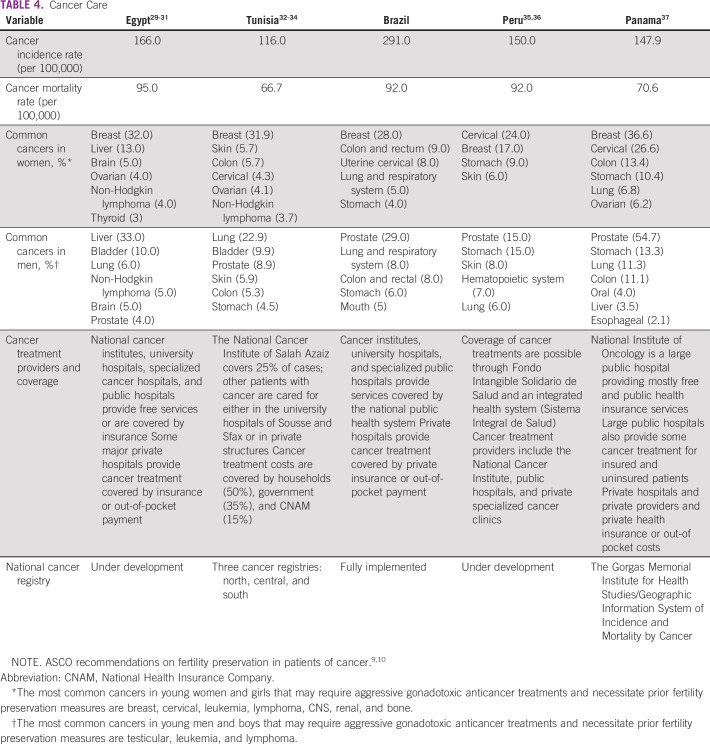

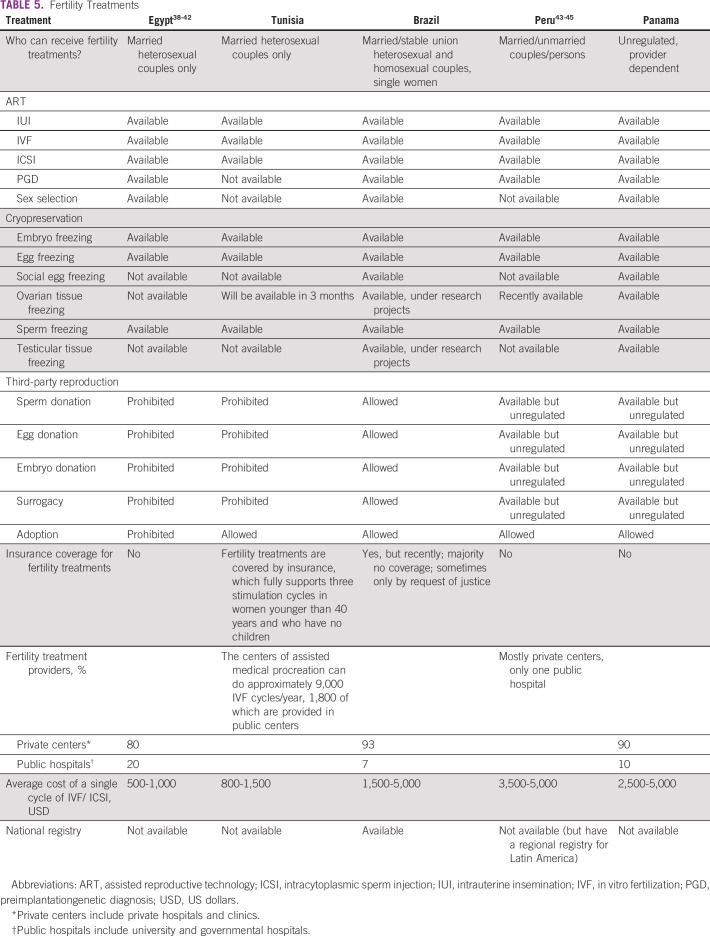

All surveyed centers from the five developing countries (Egypt, Tunisia, Brazil, Peru, and Panama) responded to all questions. Responses are listed in detail in Tables 3 to 8 (developing country profile 2015/2016, cancer care, fertility treatments, fertility preservation treatments, barriers to oncofertility, and opportunities of oncofertility, respectively).

TABLE 3.

Developing Country Profile 2015/2016

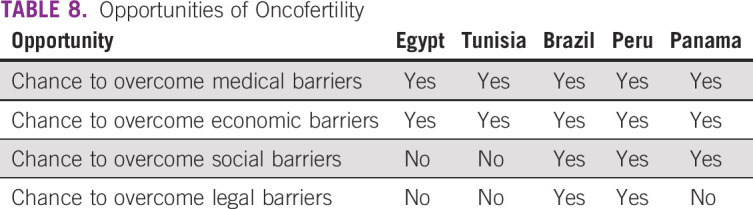

TABLE 8.

Opportunities of Oncofertility

TABLE 4.

Cancer Care

TABLE 5.

Fertility Treatments

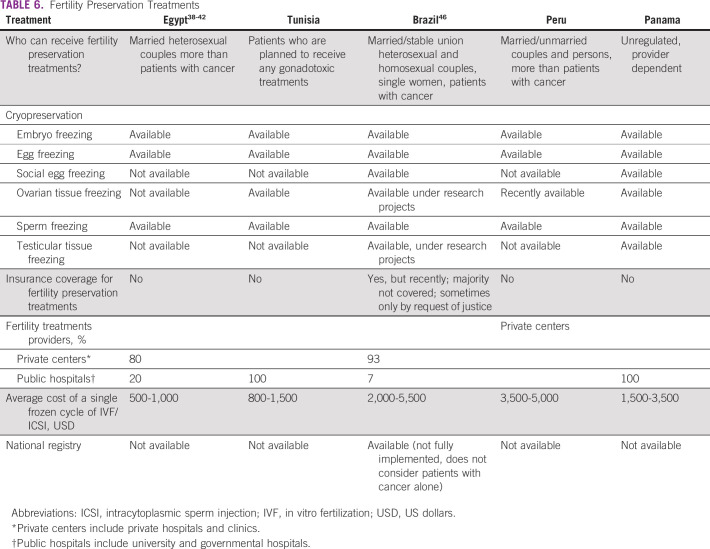

TABLE 6.

Fertility Preservation Treatments

TABLE 7.

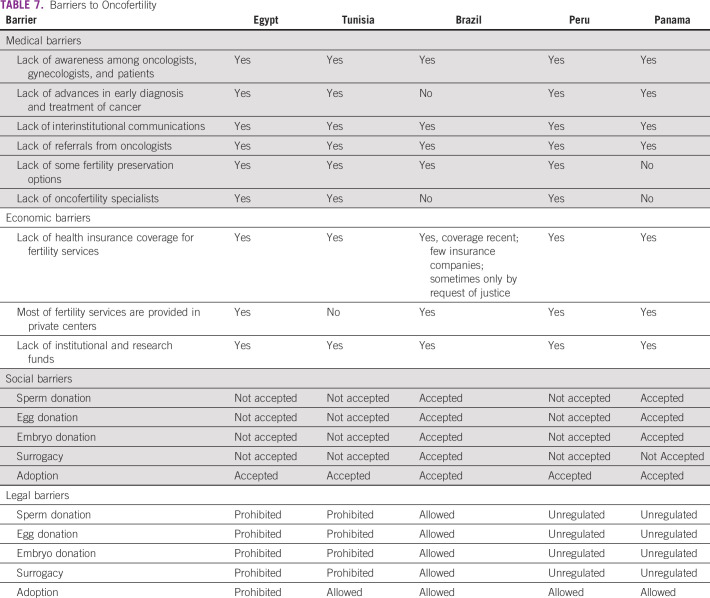

Barriers to Oncofertility

DISCUSSION

As survival rates continue to rise, the need for oncofertility services in developing countries has become increasingly apparent. Although the mortality rate remains relatively higher in developing countries than in developed ones, quality of life matters for all patients, including future fertility of adult cancer survivors. Because approximately 50% of cancer in developing countries occurs in individuals younger than 65 years,many patients are of reproductive age, and their reproductive health, including endocrine health, should be considered before treatment starts. However, with limited resources, including significant financial burdens to patients and their families such as high out-of-pocket expenses and limited insurance coverage, oncofertility services are not viewed as a necessity and are disproportionally available to affluent patients with the means to pay for these additional services. Furthermore, many providers and patients are focused on eliminating cancer and do not consider that fertility can be an important quality-of-life concern later on.

Respondents identified a number of barriers to oncofertility care in their countries. Common barriers are a lack of awareness among oncologists, lack of funds, high costs, and cultural and religious constraints that result in negative attitudes toward assisted reproduction technology and fertility preservation and oncofertility services. This general lack of awareness among providers may result in a reluctance to accept new technologies and practice.

Although survey respondents identified a number of barriers to care, these barriers can be positively viewed as opportunities for expansion, growth, and development. To facilitate collaborations and reduce duplicative efforts, the OCGPN was formed in 2012.8 The OCGPN works with reproductive specialists from 33 countries around the globe in an effort to better serve children, adolescents, young adults, and adults with cancer and other fertility-threatening diseases. It acts as an organizing center and fosters interaction among groups that can share resources, methodologies, and other experiences in the field. The establishment of a strong global network not only drives the collaborative nature of the consortium but also helps global partners to build their own programs and fertility preservation networks, as with the Brazilian Oncofertility Consortium, the Peruvian Oncofertility Network, and the Latin American Oncofertility Network. These networks were born out of the work of the OCGPN and are now models of success for future networks.

The OCGPN assists these developing countries as their programs develop and grow. All the survey respondents are current members of the consortium (Table 1), and members from both Brazil and Tunisia have adapted existing oncofertility materials to their native languages for their communities. For example, Brazil, one of the first countries to join the OCGPN, translated materials from Northwestern University’s Save My Fertility online fertility preservation toolkit47 to Portuguese so that their providers receive information in the native language. Furthermore, the group published an oncofertility textbook in Portuguese: Preservação da Fertilidade: Uma Nova Fronteira Entre Medicina Reprodutiva e Oncologia.48 This book is intended for health professionals to increase their understanding of fertility preservation in patients with cancer. Members from Aziza Othmana Hospital of Tunis, Tunisia, also translated Save My Fertility materials to French. These translation projects engage partners in consortium-wide activities, but more importantly, they bring utility to providers, patients, other health professionals in their home countries. Members of the OCGPN have hosted a number of conferences, meetings, and seminars in their home countries to educate their communities about oncofertility and fertility preservation in patients with cancer. Furthermore, the group has worked collectively on three publications that assist developing programs with justifying their program with local governmental or clinical governing bodies and with increasing awareness about oncofertility throughout their home institutions, countries, and regions.8,49,50 The goal is to reduce duplicative efforts and ease the burden of setting up an oncofertility practice in a country that may have limited resources.

Collaborations are imperative to the success of oncofertility centers in developing countries. However, networking is only one of the characteristics of a successful program. Persistence is key. With limited resources and lack of institutional support, oncofertility advocates easily could become discouraged with the process of setting up their own practice. These challenges are faced even in developed nations, and many people in the oncofertility community experience similar barriers. Even in a challenging environment, oncofertility champions must continue their work to increase awareness and advocate for increased access to fertility preservation services for cancer survivors.

Success is not defined by 100% of patients with cancer pursuing oncofertility services; success is defined simply as increased awareness among both patients and providers. Even in the United States and other developed nations, not all patients choose to pursue fertility preservation options, but the goal of the oncofertility community is to ensure that these conversations take place and that providers are empowered to navigate the complex fertility issues patients with cancer face.

This study had some limitations, including a lack of data on pediatric and adolescent and young adult cancer incidence in these countries. This patient population and their parents, guardians, and providers should be aware of the effects of cancer and cancer treatments on future fertility, reproductive health, and quality of life throughout survivorship. In the future, a similar study could examine the state of pediatric and adolescent and young adult oncofertility services in developing countries and implement strategies for increasing awareness.

Even with structural and financial limitations, there are many opportunities to expand oncofertility in developing countries. An increase of awareness about available fertility preservation options is the collective goal of the community. Continued tenacity, network building, and advocacy can accomplish this goal. The use of the services offered by the existing OCGPN will reduce duplicative efforts in developing countries. As a consequence of the unmet needs identified by survey respondents, the OCGPNC will use this survey as a baseline for developing countries to evaluate their own programs within the context of their country profile. This exercise will not only force sites to provide thorough self-evaluations, but also help them to identify shortcomings and opportunities for future development and success.

In conclusion, common barriers were identified by each country that responded to this survey. These barriers were lack of insurance coverage and high out-of-pocket costs for patients, lack of awareness among providers and patients, cultural and religious constraints, and lack of funding to help to support oncofertility programs. Despite these barriers, many opportunities exist to grow the field of oncofertility in these five developing countries. Continuing to engage stakeholders in developing countries and the use of powerful networks in the United States and other developed countries will aid in the acceptance of oncofertility on a global level.

Footnotes

Supported by the Center for Reproductive Health After Disease (P50HD076188) from the National Center for Translational Research in Reproduction and Infertility.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and Design: Mahmoud Salama, Lauren Ataman, Teresa K. Woodruff

Provision of study materials or patients: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Mohamed Khrouf

Consulting or Advisory Role: Abbott Laboratories

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck, IBSA Institut Biochimque SA

Fernando M. Reis

Honoraria: UCB (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Politec (I)

Speakers’ Bureau: Politec (I)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Politec (I)

Sergio Romero

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Oocyte maturation project, which derived into a patent application by The Free University of Brussels; the status of the patent currently is pending (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. : Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 136:E359-E3862015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66:7-302016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al. : Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64:83-1032014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodruff TK: The emergence of a new interdiscipline: Oncofertility. Cancer Treat Res 138:3-112007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodruff TK: Oncofertility: A grand collaboration between reproductive medicine and oncology. Reproduction 150:S1-S102015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeruss JS, Woodruff TK: Preservation of fertility in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 360:902-9112009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vos M, Smitz J, Woodruff TK: Fertility preservation in women with cancer. Lancet 384:1302-13102014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ataman LM, Rodrigues JK, Marinho RM, et al. : Creating a global community of practice for oncofertility. J Glob Oncol 2:83-962016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 24:2917-29312006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. : Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 31:2500-25102013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine : Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: A committee opinion. Fertil Steril 100:1214-12232013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Oncofertility Consortium : Global Oncofertility Partners. https://oncofertility.northwestern.edu/resources/global-oncofertility-partners

- 13.World Health Organization : Egypt. http://www.who.int/countries/egy/en

- 14.United Nations Development Programme : Human development reports: Egypt: Human development indicators. http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/EGY

- 15.International Monetary Fund : Arab Republic of Egypt. http://www.imf.org/external/country/EGY/index.htm

- 16.World Economic Forum : Global competitiveness index: Egypt. http://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-report-2015-2016/economies/#indexId=GCI&economy=EGY

- 17.Central Intelligence Agency : The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ts.html

- 18.World Health Rankings : Health profile: Tunisia. http://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/country-health-profile/tunisia

- 19.Oxford Business Group : Tunisian health sector to undergo overhaul. https://www.oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/annual-check-solid-foundation-sector-ready-overhaul

- 20.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica : IBGE Apresenta Nova Área Territorial Brasileira: 8.515.767,049 km2. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/2013-agencia-de-noticias/releases/14318-asi-ibge-apresenta-nova-area-territorial-brasileira-8515767049-km.html

- 21.United Nations . http://data.un.org/Country Profile.aspx?crName=BRAZIL

- 22. Dominguez J, Kim BK: Between Compliance and Conflict - East Asia, Latin America and the “New” Pax Americana. New York, NY: Routledge; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica : Principales indicadores. https://www.inei.gob.pe

- 24.The World Bank : Peru. http://data.worldbank.org/country/peru

- 25.The World Bank : GDP ranking. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/GDP-ranking-table

- 26.World Bank Group : Peru’s comprehensive health insurance and new challenges for universal coverage. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/13294

- 27.Ministerio de Salud Direccion General De Epidemiologia : Analisis de Situacion de Salud del Peru 2013. http://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/intsan/asis2012.pdf

- 28.World Health Organization : Panama. http://www.who.int/countries/pan/en

- 29.Ibrahim AS, Khaled HM, Mikhail NN, et al. : Cancer incidence in Egypt: Results of the national population-based cancer registry program. J Cancer Epidemiol 2014:437971.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egypt National Cancer Registry : Welcome. http://cancerregistry.gov.eg

- 31.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. : Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65:87-1082015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ministere De La Sante Publique: Registre Des Cancers Nord-Tunisie Donnees 2004-2006.

- 33.Societe Francaise De Parmacie Oncologique : http://sfpo.com

- 34.International Cancer Control Partnership : http://www.iccp-portal.org

- 35.Salazar MR, Regalado-Rafael R, Navarro JM, et al. : The role of the National Institute of Neoplastic Diseases in the control of cancer in Peru [in Spanish]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 30:105-1122013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peru Ministerio de Salud Direccion General de Epidemiologia : Analisis de la situación del cáncer en el Perú. Ministerio de Salud del Perú; Lima, Peru. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ministerio de Salud . https://www.ministeriodesalud.go.cr

- 38.El Gelany S, Moussa O: Reproductive health awareness among educated young women in Egypt. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 120:23-262013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serour GI: Ethical issues in human reproduction: Islamic perspectives. Gynecol Endocrinol 29:949-9522013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inhorn MC: Global infertility and the globalization of new reproductive technologies: Illustrations from Egypt. Soc Sci Med 56:1837-18512003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishihara O, Adamson GD, Dyer S, et al. : International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies: World report on assisted reproductive technologies, 2007. Fertil Steril 103:402-4132015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dyer S, Chambers GM, de Mouzon J, et al. : International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies world report: Assisted Reproductive Technology 2008, 2009 and 2010. Hum Reprod 31:1588-16092016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.SciELO : La infertilidad como problema de salud pública en el Perú 2012. http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2304-51322012000200003

- 44.Contraloria General de la República : Censos de población y vivienda. http://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/Redatam/censospma.htm

- 45.Zegers-Hochschild F, Schwarze JE, Crosby JA, et al. : Assisted reproductive techniques in Latin America: The Latin American Registry, 2013. JBRA Assist Reprod 20:49-582016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Carvalho BR, Rodrigues JK, Campos JR, et al. : Strategies to preserve the reproductive future of women after cancer. JBRA Assist Reprod 18:16-232017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Northwestern University : Save My Fertility. http://www.savemyfertility.org

- 48.Marinho RM: Preservação Da Fertilidade: Uma Nova Fronteira Em Medicina Reprodutiva E Oncologia Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Medbook Editora Cientifica; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rashedi A, de Roo SF, Ataman L, et al. : Survey of fertility preservation options available to cancer patients around the globe. J Glob Oncol 10.1200/JGO.2016.008144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rashedi A, de Roo SF, Ataman L, et al. : Survey of third-party parenting options associated with fertility preservation available to patients with cancer around the globe. J Glob Oncol 10.1200/JGO.2017.009944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]