Purpose

Oncofertility focuses on providing fertility and endocrine-sparing options to patients who undergo life-preserving but gonadotoxic cancer treatment. The resources needed to meet patient demand often are fragmented along disciplinary lines. We quantify assets and gaps in oncofertility care on a global scale.

Methods

Survey-based questionnaires were provided to 191 members of the Oncofertility Consortium Global Partners Network, a National Institutes of Health–funded organization. Responses were analyzed to measure trends and regional subtleties about patient oncofertility experiences and to analyze barriers to care at sites that provide oncofertility services.

Results

Sixty-three responses were received (response rate, 25%), and 40 were analyzed from oncofertility centers in 28 countries. Thirty of 40 survey results (75%) showed that formal referral processes and psychological care are provided to patients at the majority of sites. Fourteen of 23 respondents (61%) stated that some fertility preservation services are not offered because of cultural and legal barriers. The growth of oncofertility and its capacity to improve the lives of cancer survivors around the globe relies on concentrated efforts to increase awareness, promote collaboration, share best practices, and advocate for research funding.

Conclusion

This survey reveals global and regional successes and challenges and provides insight into what is needed to advance the field and make the discussion of fertility preservation and endocrine health a standard component of the cancer treatment plan. As the field of oncofertility continues to develop around the globe, regular assessment of both international and regional barriers to quality care must continue to guide process improvements.

INTRODUCTION

The primary goal of oncofertility is to increase access for patients with cancer to fertility counseling and fertility preservation options to improve the overall quality of life of cancer survivors.1,2 As the field of oncofertility expands, a need exists to clarify the oncofertility services that are provided on a global scale and to define the challenges faced by providers and patients. Current barriers represent areas for improvement in this growing field and can be addressed through collaboration with professional societies and governments. For these reasons, we conducted a global oncofertility resource assessment survey to document the experiences of existing oncofertility centers within the Oncofertility Consortium (OC) Global Partners Network.

METHODS

Survey Design

A survey was sent to members of the OC Global Partners Network and international experts in the field to collect information about the fertility preservation services offered to patients with cancer and the barriers to oncofertility care at their centers. The survey was written in English because all potential participants were English speaking. Invited study participants were clinicians, researchers, nurses, patient navigators, and psychologists. A pilot survey was generated for attendees of the 2015 Oncofertility Conference and after cognitive debriefing, was subsequently converted to an electronic format through the use of SurveyMonkey software. The final version was e-mailed to 191 contacts of the OC Global Partners Network. The Northwestern University institutional review board determined that the study did not constitute research that involves human subjects; therefore, additional institutional review board review and approval was not required.

Survey Inclusion/Exclusion

Upon receipt of multiple responses from the same center, scores were averaged to generate mean values. All open-ended response data provided by the study participants are reported in the results. Surveys were excluded from the analysis if respondents did not provide contact or identification information, if the survey was left blank, or if duplicate responses were submitted. Appendix Table A1 lists the countries and organizations that participated in the study.

Survey Questions

Respondents were asked a total of 12 questions about organization of referrals, patient access to medical professionals, barriers and challenges faced at centers, and estimated reimbursement of oncologic fertility preservation by governmental entities or insurance companies (Appendix Table A2). Six questions were dichotomous (yes/no), with space provided for open-ended comments (questions 1, 2, 3, 6, 10, and 11). Three questions were multiple choice, where only one answer could be selected (questions 7, 8, and 9). Two questions were multiple response where respondents could select one or more answers (questions 5 and 12). One question contained a matrix of drop-down menus where respondents could select whether a fertility preservation service is offered to specific age ranges of female and male patients (question 4).

Analysis of Survey Results

Survey responses were exported to Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). The dichotomous and multiple response questions were coded with numerical values (yes = 1, no = 2) to facilitate statistical analysis. Graphs were generated with both SPSS for Windows version 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and Microsoft Excel software. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the quantitative data. Two individuals who were blinded to the region analyzed written responses.

RESULTS

A total of 63 responses were received (response rate, 25%), and of those, 47 were valid, which resulted in the inclusion of 40 centers after combining multiple responses from the same center. Appendix Table A1 lists the participating centers by country and continent. Appendix Table A3 lists the frequencies and percentages of responses to dichotomous (yes/no) questions. The denominator for each survey question changed according to the number of responses because not all respondents opted to answer each question.

Organization of Referrals

In terms of organizational structure, 30 of 40 respondents (75%) reported having an established referral system at their site, and 35 of 40 (88%) reported having a patient registry. The largest group of respondents, 14 of 37 (38%), indicated that the average length of time at their center between cancer diagnosis and fertility preservation consultation is 1 to 2 days. Nine of 37 respondents (24%) reported that the time between consultation and fertility preservation procedures was 1 to 2 days; nine of 37 (24%) also reported the time to be 3 to 5 days between consultation and fertility preservation procedures. Eleven of 36 (31%) indicated the time between fertility preservation and cancer treatment was 3 to 5 days. (Appendix Table A4).

Respondents reported a variety of referral processes. Some centers see patients with cancer for fertility preservation counseling within 24 hours of diagnosis, such as at the IVF Centro de Reproducción in Panama and at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital in South Korea; two sites specified that the referral from cancer diagnosis to fertility consultation can take ≥ 3 weeks.

As indicated in the open-ended survey responses, oncologists refer their patients at the majority of centers (16 of 19). However, at the Centro de Preservação da Fertilidade in Portugal, Huntington Medicina Reprodutiva in Brazil, and McGill University Health Centre Reproductive Centre in Canada, patients may set up their own appointments. The Seoul National University Bundang Hospital attributed referral challenges to discrepancies between the policies that govern oncologists and reproductive physicians. At the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, Australia, the development of written informational support, clear referral pathways, and fertility preservation management protocols within the pediatric setting have doubled the rate of fertility counseling since 2013. The Clinic of Endocrinological Gynecology at the Jagiellonian University Medical College in Poland noted time burden and a lack of awareness among clinicians as its two greatest barriers to care.

Patient Access to Specialized Professionals

Nine of 34 respondents (26%) reported having a nurse navigator, social worker, or specific oncofertility patient navigator for patients with cancer of reproductive age. At the Ceará Blood Center in Fortaleza, Brazil, an oncology nurse navigator (a registered nurse with oncology-specific knowledge) offers individualized assistance to patients and their families. This patient navigator provides the education and resources necessary to expedite stressful decision making for the patient and ensures timely access to quality health and psychosocial care.

With regard to patient counseling, 30 of 40 respondents (75%) provide routine psychological support to patients. At the Centre for Fertility Preservation at the Coimbra Hospital and University Centre in Portugal, a psychologist specializes in helping patients through fertility preservation decision making after a cancer diagnosis. If the patient ultimately decides to undergo a procedure, the psychologist provides support throughout the entirety of the fertility preservation process by gauging the patient’s mental condition and emotional state.

Services Offered at the Initial Fertility Preservation Consultation

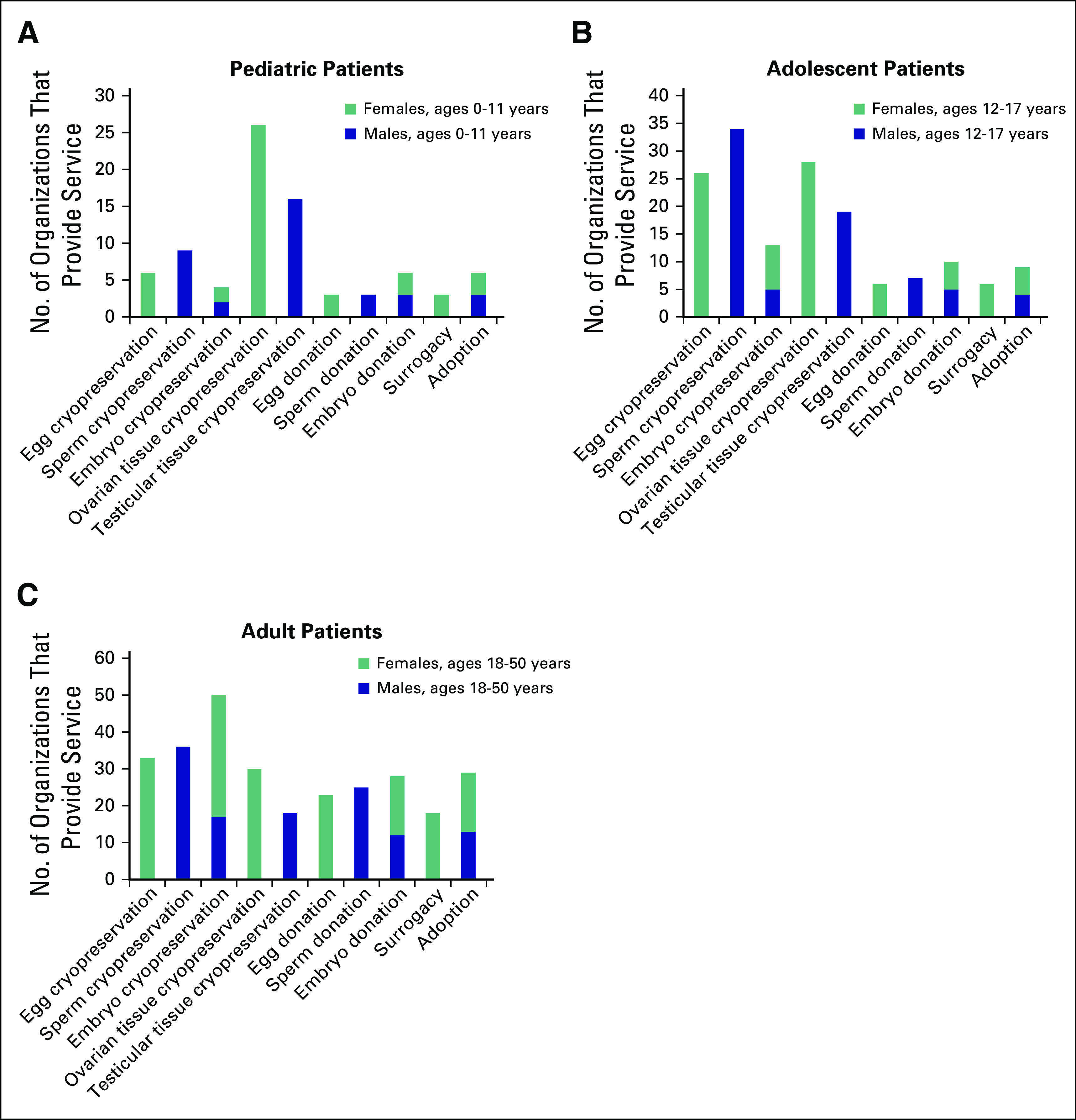

Thirty seven of 40 survey respondents (93%) identified the services offered to patients at their facilities. For pediatric males and females, the services most commonly offered are testicular tissue cryopreservation (n = 16) and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (n = 26), respectively. For adolescent males and females, sperm cryopreservation (n = 34) and egg cryopreservation (n = 26) and ovarian tissue cryopreservation (n = 28) are available options. In the adult age category, more third-party options were discussed with both males and females, including adoption (n = 29) and donation of eggs (n = 23), sperm (n = 25), and embryos (n = 28). Of the 40 respondents, only one stated that gestational surrogacy is mentioned as a future possible consideration to pediatric females; six reported mentioning gestational surrogacy to adolescent females, and 18 reported mentioning the option to adult females (Fig 1).

FIG 1.

Fertility preservation services offered to patients at survey respondent organizations. (A) Pediatric patients. (B) Adolescent patients. (C) Adult patients.

Barriers and Challenges

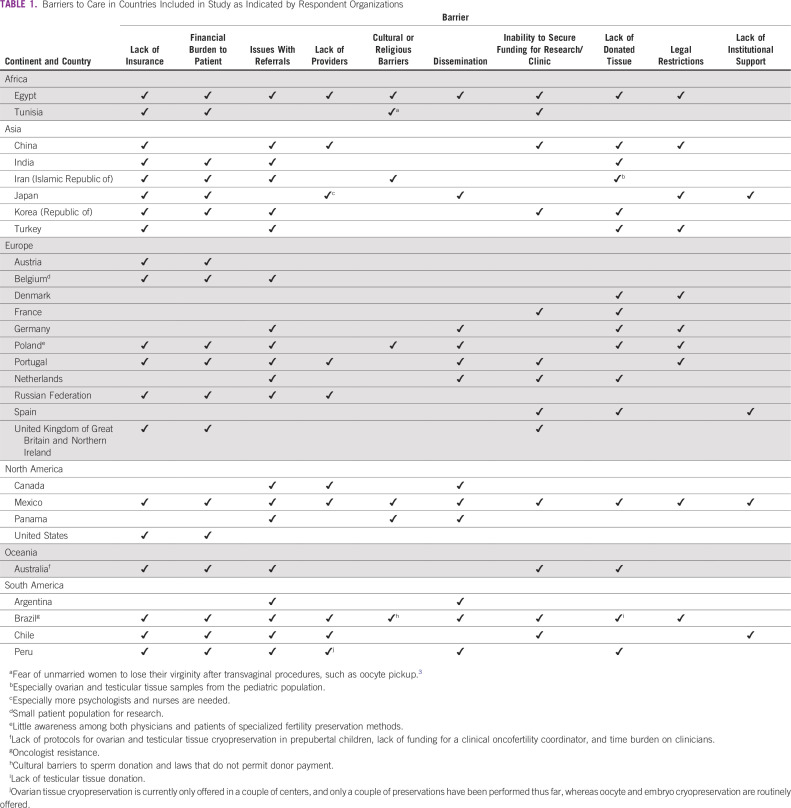

The majority of respondents, 37 of 40 (93%), identified barriers to care (Table 1). Fourteen of 23 respondents (61%) identified religious or cultural restrictions to oncofertility care offered at their sites. However, lack of insurance coverage and significant financial burden to patients were identified most often (both 62%; 23 of 37).

TABLE 1.

Barriers to Care in Countries Included in Study as Indicated by Respondent Organizations

In addition, 9 of 37 respondents (24%) indicated a lack of providers as a challenge their center faces. In Brazil, physicians’ resistance to discuss fertility issues may be one of the greatest challenges, above even the high estimated costs noted (Table 2).

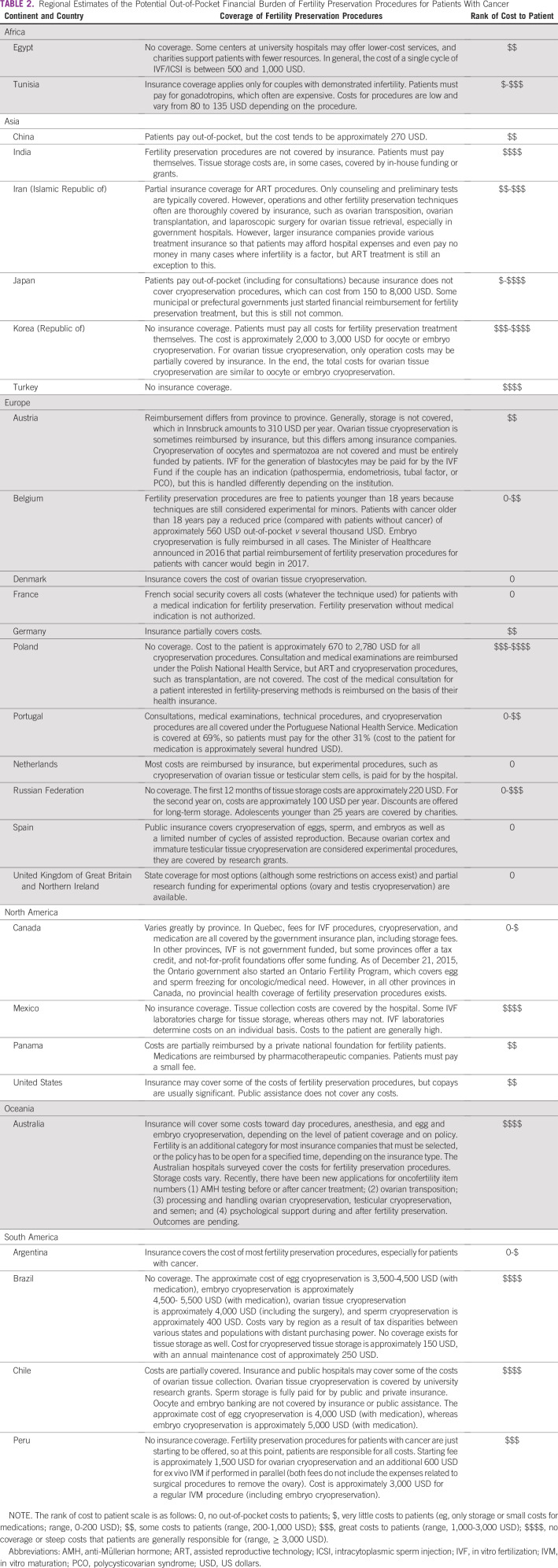

TABLE 2.

Regional Estimates of the Potential Out-of-Pocket Financial Burden of Fertility Preservation Procedures for Patients With Cancer

Eleven of 37 respondents (30%) stated that the costs of fertility preservation procedures are covered by insurance or national or provincial health systems, whereas 26 of 37 respondents, more than two thirds (70%), reported that costs are not covered (Appendix Table A3). The highest costs of oncofertility care were noted in Japan. In Gifu, oncofertility procedure costs were reported to be as high as 5,000 US dollars (USD) per patient for ovarian tissue cryopreservation, with sperm cryopreservation costing only approximately 150 USD and egg and embryo cryopreservation costing from 2,500 to 3,500 USD per patient. Respondents from St Mariana University in Kawasaki reported even higher costs for oncofertility procedures, which range from 6,000 to 8,000 USD. In contrast, at the Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands, all fertility preservation options are reimbursed by insurance or the hospital (Table 2).

The survey responses indicated various legal challenges about specific procedures. One notable cultural and legal barrier to oncofertility care was related to the use of surrogacy. This topic is explored in the accompanying article.4

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found global trends in the services offered to pediatric, adolescent, and young adult patients with cancer, including some notable regional differences, and learned more about challenges and barriers to care. The information gathered in this analysis would be stronger with a higher response rate and a field-wide study population. The OC Global Partners Network was recently founded in 2013, so the survey respondents were limited to the current members of the group at the time of this study. This cohort of professionals was selected because of their declared commitment to the field of oncofertility and ease of contact. However, it is important to recognize that those surveyed are considered leaders in oncofertility care, and as a result, the findings may highlight the most successful settings. An online survey and the existence of language barriers could have contributed to the relatively low response rate, although the response rate is comparable to other clinical surveys.5

An oncofertility consult ideally occurs in the short window of time between a cancer diagnosis and the start of treatment. A major goal of the field is for this conversation to become routine practice in cancer treatment.6 Timely referral of a patient with a new diagnosis by an oncologist to a reproductive endocrinologist is vital and requires an effective connection between the two medical specialists. Studies show that fewer than one half of reproductive-age patients who undergo cancer treatment are referred to endocrinology specialists despite recommendations from ASCO;7 this is due to a combination of factors, including a lack of knowledge among oncologists, a hesitance of patients to bring up their desire to preserve their fertility, and the inability to delay treatment of aggressive cancers.8 As a result of these obstacles, patient navigators9 and established referral processes are critical to ensure patients receive the best and most efficient fertility preservation care possible. The current results are consistent with this observed disconnect, with only one quarter of survey respondents reporting the use of specialized oncofertility navigators.

In addition, national registries are ideal for collecting population data, which can be useful for evaluating the success of fertility preservation referrals. The majority of centers included in this study confirmed that they have established oncofertility registries. In 2015, the Fertility Understanding Through Registry and Evaluation (FUTURE) research group launched the first Web- and population-based national oncofertility registry in Australia and New Zealand.10 These databases track patient-specific information, including demographic details, cancer stage, and fertility-related issues as a result of cancer or its treatment.11 FUTURE is expected to be a leading model for other countries to highlight their own systems’ assets as well as to identify their unmet needs.

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine and ASCO recommend that psychological counseling be offered before cancer treatment.12,13 Ready access to a psychologist during the fertility preservation counseling process has been shown to help to reduce patient anxiety as well as enhance communication between relevant medical professionals because the patient’s individual needs are more readily identified.14 Moreover, a marked reduction in anxiety and depression is seen in patients who receive structured cognitive behavioral counseling.15 Specialized counseling is associated with higher quality-of-life indications and less regret.1 The fact that 30 of 40 (75%) of the oncofertility centers surveyed provide formal psychological counseling to patients with cancer is encouraging.

The ability to have one’s own biologic children is a priority to patients with cancer, and fertility loss can be a source of significant distress.15 ASCO published updated guidelines in 2013 that recommend that oncologists discuss fertility preservation options with patients at risk for infertility as a result of their treatment.8 Resistance among oncologists to discuss fertility issues may be due to physicians’ desire to treat cancers as quickly as possible and to prioritize discussions about cancer therapy and management. Studies have found that when the prognosis is poor, oncologists are less likely to refer patients to reproductive endocrinology specialists or to bring up fertility discussions at all.8 Physician reluctance to discuss fertility could also be due to a lack of awareness of oncofertility developments, a lack of time, or a lack of site-specific guidelines, especially with regard to treating pediatric patients.8,16,17 Global strides must still be made to educate oncologists about oncofertility, the fertility preservation options available to patients, and the importance of discussing fertility with patients at the time of diagnosis.

To our knowledge, the costs and legal restrictions to care in the field of oncofertility have never been systematically identified or analyzed by region or center. This information should be readily accessible to patients and providers. Specifically, egg, sperm, and embryo donation often may not be accessible and for this reason, not discussed as a future option at the initial consultation because of financial, cultural, and legal restraints. Specifically, the respondents from the Banco de Sêmen do Rio de Janeiro in Brazil stated that the lack of compensation for sperm donors is a huge barrier to providing this service to their patients. Cultural customs play a significant role in the regulation of third-party assisted reproductive technologies, which are explicitly observed in two surveyed countries, Egypt and Tunisia. Both countries outlaw egg, sperm, and embryo donation.18

Lack of insurance coverage poses a great barrier to patient access to oncofertility care.19,20 Of note, insurance in Tunisia only covers costs of fertility preservation procedures in cases where a couple has demonstrated infertility. Infertility is difficult, if not impossible, for pediatric and unmarried patients to prove, which imposes an undue financial challenge to this proportion of oncofertility patients. Costs for fertility preservation procedures in Tunisia remain lower than at other sites, but only approximately 50% of patients follow through with procedures because of the high cost of gonadotropins.

In the United States, a paradox exists about insurance coverage of fertility preservation procedures. Insurance generally covers the costs of iatrogenic conditions that result from cancer treatment, such as mastectomy and wigs for alopecia.21 However, despite the fact that infertility as a result of cancer is iatrogenic, fertility preservation procedures are considered an exception and often are not covered by government-subsidized national insurance or private companies.21 Insurance companies require burden of proof for infertility; therefore, couples must demonstrate 1 year of unsuccessful attempts to conceive before they receive the diagnosis of infertility. This policy is unacceptable because fertility preservation addresses the potential future infertility of currently fertile individuals.21 Changes in policy are needed to ensure that all iatrogenic conditions after cancer treatment are covered by national health insurance systems, and hopefully, private insurers will follow suit.

As of 2016, 31 countries are part of the surveyed OC Global Partners Network. This list is not exhaustive, and oncofertility practicing organizations in other countries were not included in this analysis. That said, this study represents a first attempt to quantify services in this emerging discipline. Fertility management is complex and must take into account culturally sensitive attitudes within each region of the world, and reanalysis of the services provided is important as this field expands.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank all members of the OC Global Partners Network for their hard work and dedication to oncofertility.

Appendix

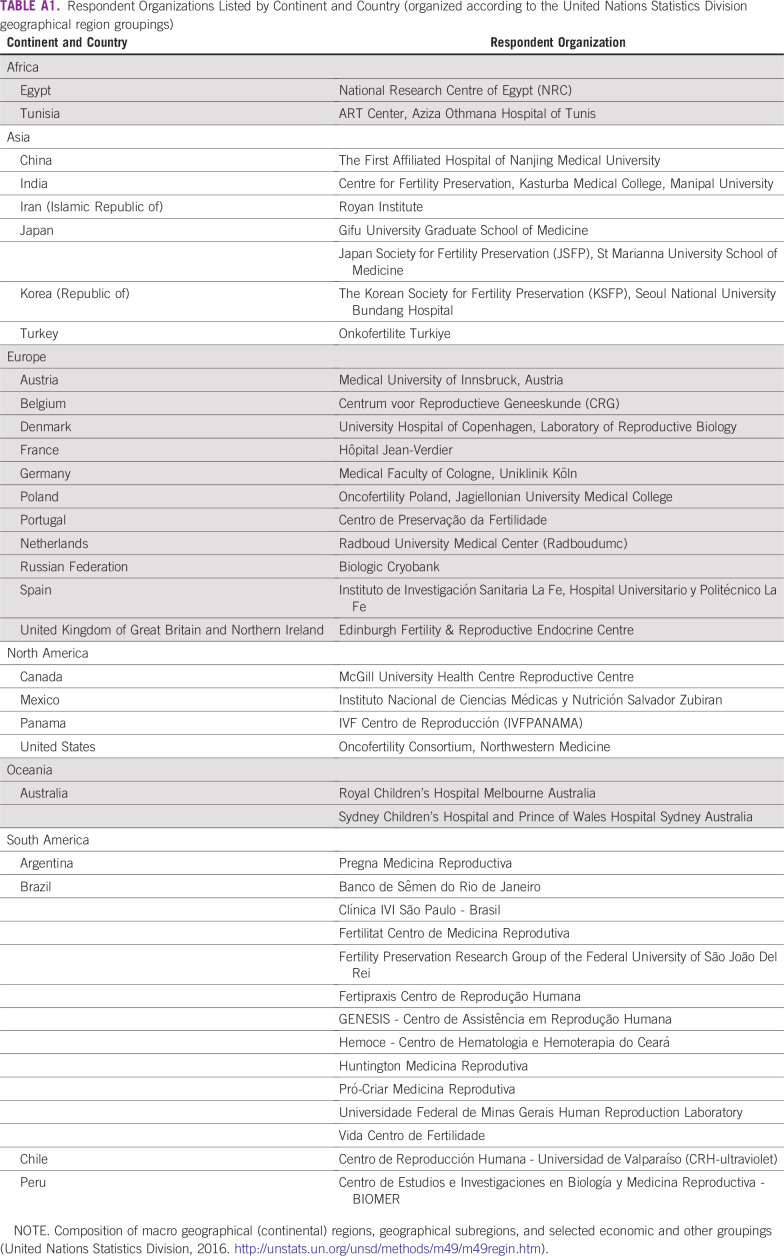

TABLE A1.

Respondent Organizations Listed by Continent and Country (organized according to the United Nations Statistics Division geographical region groupings)

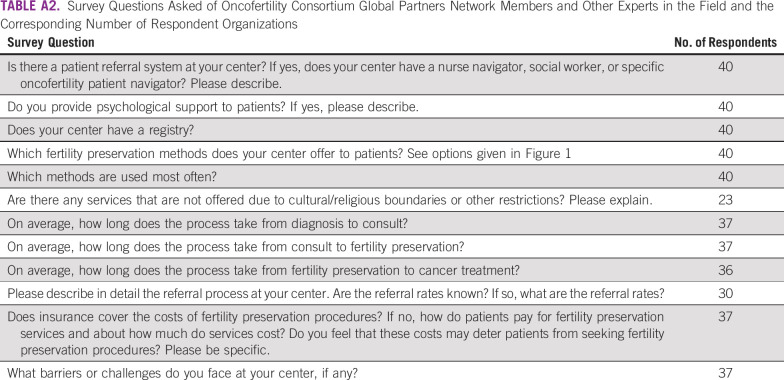

TABLE A2.

Survey Questions Asked of Oncofertility Consortium Global Partners Network Members and Other Experts in the Field and the Corresponding Number of Respondent Organizations

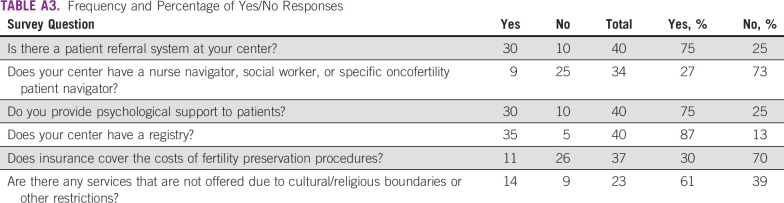

TABLE A3.

Frequency and Percentage of Yes/No Responses

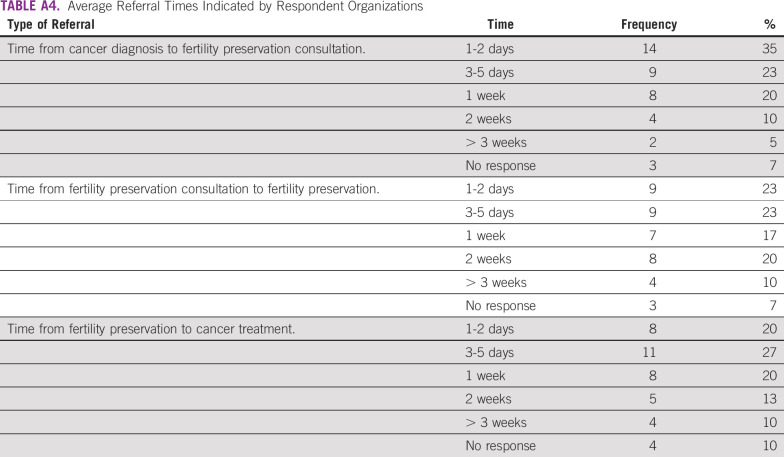

TABLE A4.

Average Referral Times Indicated by Respondent Organizations

Footnotes

Supported by the Center for Reproductive Health After Disease (P50HD076188) from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Translational Research in Reproduction and Infertility.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Alexandra S. Rashedi, Lauren M. Ataman, Catharina C.M. Beerendonk, Teresa K. Woodruff

Administrative support: Alexandra S. Rashedi, Lauren M. Ataman

Provision of study materials: Teresa K. Woodruff

Collection and assembly of data: Alexandra S. Rashedi, Saskia F. de Roo, Lauren M. Ataman, Teresa K. Woodruff

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Alexandra S. Rashedi

Employment: Cigna (I)

Stock or Other Ownership: Cigna (I)

Antoinette Anazodo

Research Funding: Merck Serono

Cassio Sartorio

Employment: Vida Centro de Fertilidade

Leadership: Vida Centro de Fertilidade

Stock or Other Ownership: Vida Centro de Fertilidade

Catharina C.M. Beerendonk

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Goodlife

Ellen M. Greenblatt

Consulting or Advisory Role: Ferring Pharmaceuticals, EMD Serono

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: EMD Serono

Fernando M. Reis

Honoraria: Politec Saúde (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Politec Saúde (I)

Speakers’ Bureau: UCB (I)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Abbott Laboratories (I)

Johan Smitz

Speakers’ Bureau: Ferring Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Ferring Pharmaceuticals

Maria T. Bourlon

Leadership: Medivation, Astellas Pharma

Honoraria: Medivation, Astellas Pharma

Speakers’ Bureau: Asofarma

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen Pharmaceuticals

Michel De Vos

Honoraria: Cook Medical

Research Funding: Cook Medical

Richard A. Anderson

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, HRA Pharma, NeRe Pharmaceuticals

Speakers’ Bureau: Roche, Beckman Coulter, IBSA Institut Biochimque

Research Funding: Ferring Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: IBSA Institut Biochimque

Roberto de A. Antunes

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck Serono

Speakers’ Bureau: Merck Serono

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck Serono, MSD

Teresa Almeida-Santos

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, MSD

Research Funding: Merck

Teresa K. Woodruff

Research Funding: Ferring Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Letourneau JM; Ebbel EE Katz PP et al. : Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer. Cancer 118:1710-1717, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Vos M, Smitz J, Woodruff TK: Fertility preservation in women with cancer. Lancet 384:1302-1310, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khrouf M, Bouyahia M, Berjeb K, et al: Perurethral transvesical route for oocyte retrieval: An old technique for a new indication. Fertil Steril 106:e129, 2016 (suppl 3) [Google Scholar]

- 4. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2017.009944. Rashedi AS, de Roo SF, Ataman LM, et al: Survey of third-party parenting options associated with fertility preservation available to patients with cancer around the globe. J Glob Oncol doi: 10.1200/JGO.2017.009944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, et al. : Exploring physician specialist response rates to Web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 15:32, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonçalves V, Sehovic I, Quinn G: Childbearing attitudes and decisions of young breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 20:279-292, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, Lee JH, et al. : Physician referral for fertility preservation in oncology patients: A national study of practice behaviors. J Clin Oncol 27:5952-5957, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonçalves V, Tarrier N, Quinn G: Thinking about white bears: Fertility issues in young breast cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns 98:125-126, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262. Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL: History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 117:3539-3542, 2011 (suppl 15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ataman LM, Rodrigues JK, Marinho RM, et al. : Creating a global community of practice for oncofertility. J Glob Oncol 2:83-96, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anazodo AC, Stern CJ, McLachlan RI, et al. : A study protocol for the Australasian Oncofertility Registry: Monitoring referral patterns and the uptake, quality, and complications of fertility preservation strategies in Australia and New Zealand. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 5:215-225, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ethics Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine : Fertility preservation and reproduction in patients facing gonadotoxic therapies: A committee opinion. Fertil Steril 100:1224-1231, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. : Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 31:2500-2510, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Razzano A, Revelli A, Delle Piane L, et al. : Fertility preservation program before ovarotoxic oncostatic treatments: Role of the psychological support in managing emotional aspects. Gynecol Endocrinol 30:822-824, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 24:2917-2931, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McQuillan SK, Malenfant D, Jayasinghe YL, et al. : Audit of current fertility preservation strategies used by individual pediatric oncologists throughout Australia and New Zealand. J Pediatr Oncol 1:112-118, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knight S, Lorenzo A, Maloney AM, et al. : An approach to fertility preservation in prepubertal and postpubertal females: A critical review of current literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62:935-939, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Center for Ethics and Law in Biomedicine: Annual Report. Budapest, Hungary, 2006.

- 19.Berg Brigham K, Cadier B, Chevreul K: The diversity of regulation and public financing of IVF in Europe and its impact on utilization. Hum Reprod 28:666-675, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambers GM, Sullivan EA, Ishihara O, et al. : The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: A review of selected developed countries. Fertil Steril 91:2281-2294, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campo-Engelstein L: Consistency in insurance coverage for iatrogenic conditions resulting from cancer treatment including fertility preservation. J Clin Oncol 28:1284-1286, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]