Abstract

Background and aim:

Medically managed opioid withdrawal (detox) can increase the risk of subsequent opioid overdose. We assessed the association between mortality following detox and receipt of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and residential treatment after detox.

Design:

Cohort study generated from individually linked public health datasets

Setting:

Massachusetts, USA

Participants:

30,681 opioid detox patients with 61,819 detox episodes between 2012–2014

Measurements:

Treatment categories included no post-detox treatment, MOUD, residential treatment, or both MOUD and residential treatment identified at monthly intervals. We classified treatment exposures in two ways: a) ‘On Treatment’ included any month where a treatment was received, b) ‘With Discontinuation’ individuals were considered exposed through the month following treatment discontinuation. We conducted multivariable Cox proportional hazards analyses and extended Kaplan-Meier estimator cumulative incidence for all-cause and opioid-related mortality for the treatment categories as monthly time varying exposure variables.

Findings:

Twelve months after detox, 41% received MOUD for a median of 3 months, 35% received residential treatment for a median of 2 months, and 13% received both for a median of 5 months. In On Treatment analyses for all-cause mortality, compared with no treatment, adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) were 0.33 (95% CI: 0.26–0.43) for MOUD, 0.63 (95% CI: 0.47–0.84) for residential treatment, and 0.11 (95% CI: 0.03–0.42) for both. In With Discontinuation analyses for all-cause mortality, compared with no treatment, AHRs were 0.51 (95% CI: 0.42–0.62) for MOUD, 0.76 (95% CI: 0.59–0.96) for residential treatment, and 0.20 (95% CI:0.08–0.55) for both. Results were similar for opioid-related overdose mortality.

Conclusions:

Among people who have undergone medically managed opioid withdrawal, receipt of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), residential treatment, or the combination of MOUD and residential treatment were associated with substantially reduced mortality compared with no treatment.

Introduction:

In the United States, there were 47,600 opioid-involved overdose deaths in 2017, a 12% increase from 2016.1 The link between underlying opioid use disorder (OUD) and opioid overdose death is strong.2–4 Individuals with OUD often seek treatment through inpatient medically managed withdrawal programs, also known as “detox” programs. Detox programs also treat individuals with alcohol use disorder in similar fashion but using medications for alcohol withdrawal symptoms. Individuals with OUD entering detox are offered either an opioid agonist, such as methadone or buprenorphine, or a combination of non-opioid alternatives, such as clonidine, anti-cholinergics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and benzodiazepines to treat the symptoms of withdrawal. These programs typically conform to the characteristics of Level 3.7 and higher of the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s (ASAM) Criteria.5 Medications are tapered over 5–10 days as withdrawal symptoms subside, resulting in a reduction in physical dependence. Concomitantly there is a reduction in opioid tolerance. Optimally, detox is followed by further treatment with additional inpatient treatment, psychotherapy and/or medications for opioid use disorders (MOUD). However, linkage to further treatment often does not occur, even though most individuals are interested. 6–10

Because detox without further treatment only addresses physical dependence in the short term, but does not address the underlying chronic disease, relapse to opioid use is common.11–13 And because tolerance is reduced by detox, at the time of relapse, risk for overdose and death is high.4,14–18 In Massachusetts, the age and gender standardized mortality ratio for opioid detox patients was extremely high at 66, and the population attributable fraction for detox patients and opioid overdose death was 0.19.19 MOUD, including methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone, are FDA-approved and demonstrated to reduce opioid use, increase engagement in other treatment, and for methadone and buprenorphine, are associated with reduced opioid overdose and all-cause mortality risk. 20–25 Thus, the traditional detox episode presents an irony to patients and providers – while the intention is to engage individuals into treatment, 13–36% of detox patients are linked to further treatment, resulting in high risk for relapse and overdose.7,26,27 Further inpatient treatment, which typically includes less medically intensive clinical stabilization and transitional support programs and long-term residential programs that facilitate the progressive re-engagement in work and community life (half-way houses), may provide the opportunity for patients to engage in cognitive behavioral relapse prevention therapy, stabilize in recovery, and address socio-economic challenges. A 2008 study of Medicaid billing data from 10 states showed that, among patients with a substance use disorder (SUD) who were discharged from either inpatient hospitalization or detox treatment, post-discharge MOUD and inpatient treatment were both associated with reduced hospital or detox readmission for SUD or mental health condition.26 An Italian study showed reduced overdose rates among patients in therapeutic communities, a type of residential care, that was limited to the time in treatment.16

In order to understand better the causes and potential solutions to rising deaths among people using opioids, we used a linked statewide population-level dataset from Massachusetts to: 1) describe medication and inpatient treatment for OUD after inpatient medically managed opioid withdrawal (detox) and 2) determine the association between receiving these treatments for OUD after detox and opioid-related and all-cause and opioid mortality. We hypothesized that MOUD and further inpatient treatment after opioid detoxification treatment would be associated with reduced risk of opioid-related and all-cause mortality.

Methods:

Study design and data source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Massachusetts Public Health Data Warehouse (PHD). This data warehouse was established initially as part of a Massachusetts (MA) legislative mandate and is overseen by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. PHD includes data between 2011 and 2015 on residents ages 11 years or older with health insurance as reported in the MA All-Payer Claims Database (APCD), representing more than 98% of MA residents. Data from APCD were linked at the individual level with records from other datasets using a multistage deterministic linkage technique as described elsewhere.28 This work was mandated by Massachusetts law and conducted by a public health authority where no IRB review was required. The Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board also determined that this study was not human subjects research. The primary research question and analysis plan were not pre-registered on a publicly available platform and thus the results should be considered exploratory.

Cohort selection

We included individuals in the Bureau of Substance Addiction Services (BSAS) dataset with an opioid-related inpatient medically managed withdrawal treatment (detox) episode between January 2012 and December 2014, allowing twelve months observation prior to and following the first recorded detox episode. BSAS is the licensing and regulating agency for addiction treatment services in Massachusetts and contracts with programs to treat the uninsured and to cover services not offered by other payers including Medicaid (i.e.; long term residential). BSAS-contracted inpatient medically managed withdrawal programs, clinical stabilization, transitional support and long-term residential programs are required to report patient level data to BSAS for each treatment episode. These data include an indicator variable of the primary substance which we used to determine whether the detox episodes were opioid-related. In order to ensure that these episodes were distinct, we excluded recurrent detox episodes within 30 days. We restricted the cohort to people 18 years and older because medically managed withdrawal and MOUD treatment access is substantially different in adolescents compared with adults.29 We excluded individuals with evidence of cancer at any time in the five-year study period of the PHD due to high competing mortality risk. Cancer was identified using ICD-9 diagnosis codes in APCD (Supplement) or entry in the state-based cancer registry. We also excluded individuals with unknown date of birth or sex.

Recurrent detox and censoring

Recurrent detox episodes on the same individual were common. Therefore, we included follow-up up to the first five qualifying detox episodes for each individual, which accounted for 93% of the detox episodes within the window. For each detox episode, follow-up started at month of detox and ended at the earliest date of death, recurrent detox episode, or 12 months after detox. Those who were censored at a recurrent detox episode were re-entered into the cohort as a new episode.

Exposure definition

The exposure of interest in our main analysis was a categorical variable with four mutually exclusive and time-varying event categories: i) no treatment, ii) MOUD, iii) residential treatment, and iv) concomitant MOUD and residential treatment in each month after detox. Because methadone and residential treatment episodes were only available at monthly intervals, we identified MOUD and residential treatment episodes in monthly intervals, meaning if treatment was received for 1 day or more in a month, then the month was a treatment month. MOUD included treatment with methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone in a month. We identified exposure to methadone maintenance treatment in two ways: a medical claim from APCD for methadone administration via Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code H0020, or a record of treatment with methadone from BSAS data. Treatment with buprenorphine was identified via dispensing in the prescription monitoring program (PMP) for buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone. Naltrexone was identified via a pharmacy claim for injectable or oral naltrexone in the APCD. Residential treatment included postdetoxification short-term residential and long-term residential recorded in the BSAS treatment data. To describe the cohort at the individual level, we classified individuals into four mutually exclusive categories of OUD treatment in the 12 months following the index overdose: never received any treatment, ≥1 months of MOUD and no inpatient treatment, ≥1 months of inpatient treatment and no MOUD, and ≥1 months each of MOUD and inpatient treatment.

Outcome

The outcomes of interest, that were examined in separate analyses, were all-cause and opioid-related mortality as identified in death files. Classification of opioid-related death was based on medical examiner determination or standardized assessment by Massachusetts Department of Public Health (Supplement).

Confounders

We recorded the following potentially confounding variables at or in the 12 months before the index detox episode: sex, age (18–29, 30–44, and ≥ 45 years), and diagnosis of anxiety or depression defined using ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnosis codes from APCD (Supplement), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, and other non-Hispanic) from the BSAS treatment dataset, monthly dispensing of opioids and benzodiazepines from the PMP, nonfatal overdoes episode (an ambulance encounter for overdose in the Massachusetts Ambulance Trip Record Information System or hospital encounter in Case Mix) and release from incarceration in either the Department of Correction or House of Correction. For homelessness, we used a previously defined dichotomous variable in the PHD (Supplement).9

Statistical analysis

To describe individual-level cohorts, we compared characteristics recorded at the index detox episode using chi-squared tests. We also calculated the proportion of individuals receiving MOUD and inpatient treatment before and after the index inpatient detox episode, as well as, the median time in months spent on each of these treatments after detox episodes.

Extended Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence was estimated using follow-up after each detox episode where the exposure variable was the four mutually exclusive and time-varying OUD categories.30 To account for follow-up intervals defined by multiple detox episodes on the same individuals, we fit a Cox proportional hazards discrete time model in which the time zero was reset to zero at each new detox episode and stratified by prior number of detox episodes 31, 32 To ensure that there was not substantial interdependence across successive episodes, we ran separate models for each detox episode and we found no substantive changes or trends in the parameter estimates across different episodes. The model was adjusted for the confounders defined above, as well as, MOUD or residential treatment within twelve months before the index detox episode. Receipt of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines in each month after discharge from detox were included as time-varying covariates.

We defined the time-varying exposure variable in two different ways (Supplement Figure). In our primary approach, we defined the “on treatment” exposure variable, in which we considered individuals exposed to OUD treatment only in months OUD treatment was received. Several studies have demonstrated an increased risk of all-cause and opioid-related mortality in the four week period immediately following MOUD discontinuation.16,24,25 Thus, as a sensitivity analysis, we also defined a “with discontinuation” classification to attribute any impact of discontinuation to the last OUD treatment. For the “with discontinuation” classification, we attributed the mortality outcomes that occurred during the first month with “no treatment” to the treatment category received in the prior month.

We calculated the E-value to identify how strong an unmeasured confounder would need to be associated with the treatment and outcome to explain observed associations between OUD treatment and mortality.33 The PHD requires cell suppression of any counts between 1 and 10 to reduce the risk that data will be attributable to particular individuals. We used SAS Studio version 3.6 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for analyses.

Results:

Baseline Characteristics

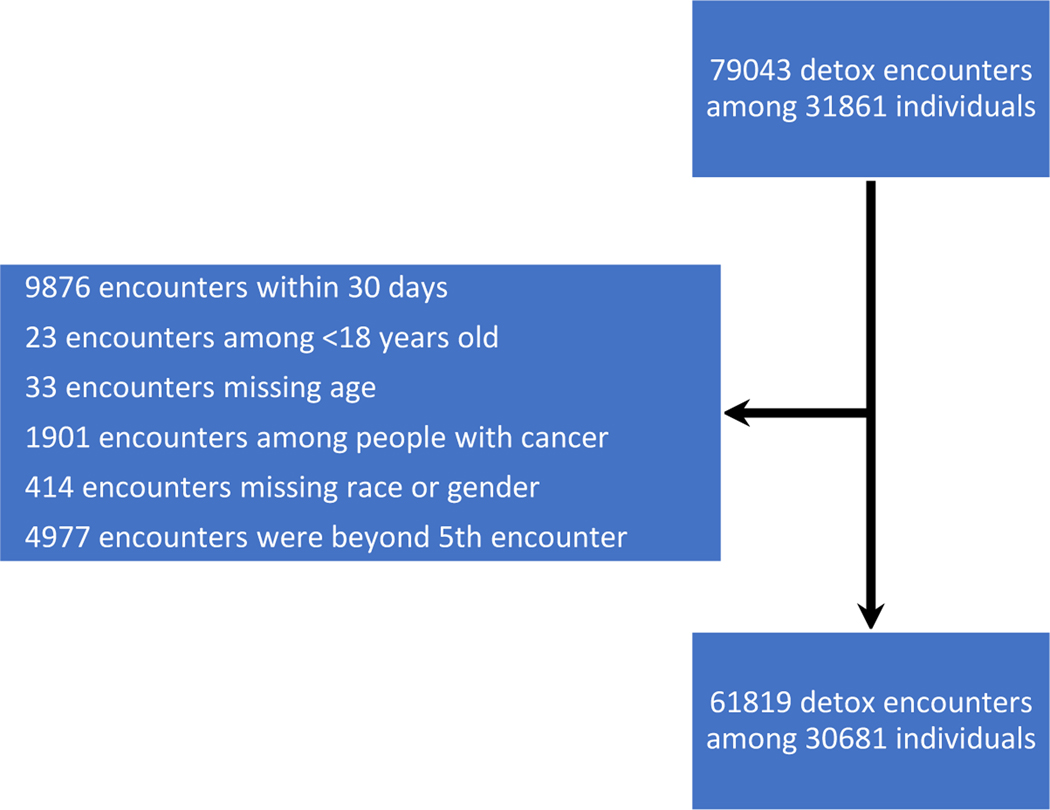

The database included 79,043 detox episodes among 31,861 individuals. Among them, 1940 individuals had 6 or more detox episodes which were excluded, and 57 deaths occurred after these detox episodes which were not included. After exclusions (Figure 1), the analytic cohort consisted of 61,819 detox episodes among 30,681 adult Massachusetts residents who were treated in inpatient detox programs for opioid withdrawal between 2012 and 2014. Two thirds (20,944) were male, 86% (26311) were less than 45 years old, 81% (24,710) were white, and 23% (6,900) were homeless. (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cohort exclusions for detox episodes, Massachusetts, 2012–2014

Table 1.

Patient characteristics prior to index detox episode by receipt of subsequent inpatient treatment or medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) following initial detox program - Massachusetts 2012–2014

| Baseline Characteristics‡ | Full Cohort (n=30,681) | MOUD and inpatient treatment in the 12 months following index detox episode† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No treatment (n=9,386) | MOUD (n=9,990) | Further inpatient (n=5,829) | Both inpatient and MOUD* (n=5,476) | ||

| Male | 68% (20944) | 74% (6966) | 65% (6511) | 71% (4123) | 61% (3344) |

| Age, in years | |||||

| 18–29 | 46% (14084) | 43% (4027) | 43% (4335) | 49% (2841) | 53% (2881) |

| 30–44 | 40% (12227) | 39% (3661) | 43% (4252) | 38% (2222) | 38% (2092) |

| ≥ 45 | 14% (4370) | 18% (1698) | 14% (1403) | 13% (766) | 9.2% (503) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 81% (24710) | 77% (7190) | 82% (8205) | 90% (4669) | 85% (4646) |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 4.1% (1249) | 5.7% (536) | 2.7% (269) | 5.4% (312) | 2.4% (132) |

| Asian/PI non-Hispanic | 0.39% (121) | 0.54% (51) | 0.30% (30) | 0.41% (24) | 0.29% (16) |

| Hispanic | 12% (3781) | 15% (1399) | 13% (1261) | 11% (636) | 8.9% (485) |

| American Indian or Other | 2.7% (820) | 2.2% (210) | 2.3% (225) | 3.2% (188) | 3.6% (197) |

| Homeless | 23% (6900) | 18% (1684) | 17% (1716) | 28% (1631) | 34% (1869) |

| Anxiety diagnosis before detox | 9.0% (2748) | 7.4% (692) | 9.7% (973) | 7.8% (456) | 12% (627) |

| Depression diagnosis before detox | 11% (3370) | 9.2% (863) | 12% (1210) | 9.9% (576) | 13% (721) |

| Incarceration before detox | 6.0% (1825) | 5.2% (484) | 4.7% (471) | 7.5% (434) | 8.0% (436) |

| Non-fatal overdose before detox | 5.3% (1621) | 4.5% (420) | 4.4% (441) | 6.4% (370) | 7.1% (390) |

| Treatment before detox | |||||

| Methadone maintenance treatment | 13% (3954) | 6.6% (616) | 19% (1868) | 7.8% (457) | 19% (1013) |

| Buprenorphine | 21% (6383) | 9.9% (933) | 31% (3050) | 12% (689) | 31% (1711) |

| Naltrexone | 3.5% (1064) | 2.3% (212) | 3.1% (314) | 4.2% (243) | 5.4% (295) |

| Detox Treatment | 22% (6821) | 17% (1573) | 18% (1804) | 29% (1709) | 32% (1735) |

| Short-term residential§ | 9.2% (2821) | 4.5% (420) | 4.7% (465) | 17% (984) | 17% (952) |

| Long-term residential | 8.2% (2510) | 4.4% (409) | 4.2% (422) | 14% (841) | 15% (838) |

| Opioid prescription | 36% (11030) | 35% (3326) | 40% (3961) | 31% (1829) | 35% (1914) |

| Benzodiazepine prescription | 19% (5857) | 16% (1472) | 23% (2282) | 15% (876) | 22% (1227) |

MOUD and inpatient at some point 12 months after inpatient detox, not necessarily at the same time.

p<0.001 for chi-square comparison of each baseline characteristic category [except receipt of opioid prescription (p=0.003)] by five post-overdose MOUD receipt categories.

Received respective diagnosis, medication, or service in one or more months in the twelve months preceding the index inpatient detox episode.

Clinical Stabilization/Step Down Services (CSS) or Transitional Support Services (TSS)

Receipt of OUD Treatment Before and After Inpatient Detox Episodes

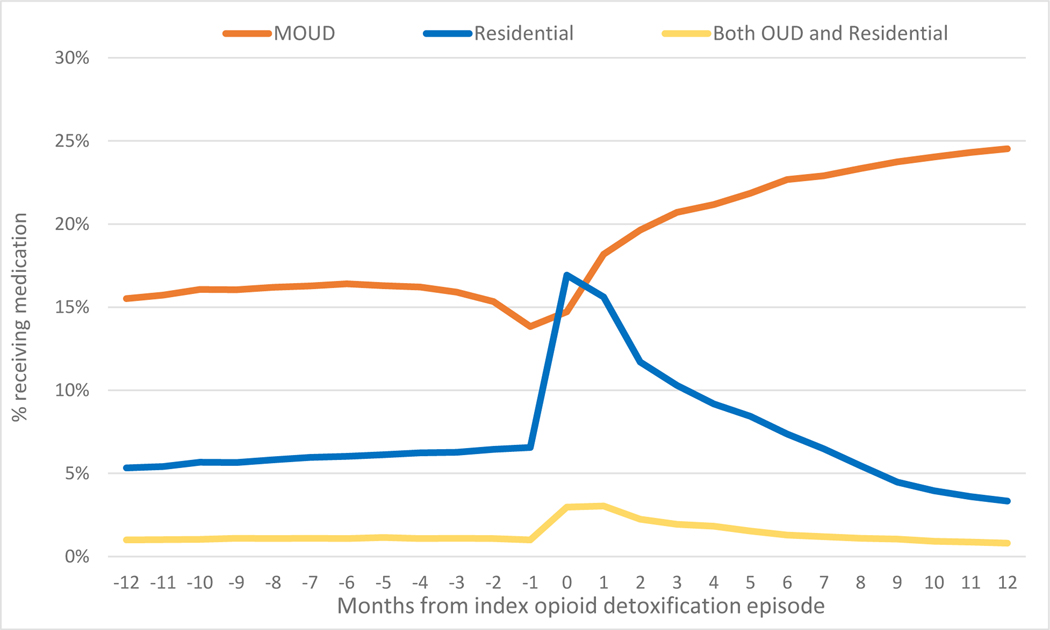

For most of the year prior to a detox episode, 16% of individuals were receiving MOUD. At the month before and month of the detox episode, MOUD dropped to 14%. After detox, the proportion of patients receiving MOUD per month climbed to 25% in month 12. Residential treatment minimally increased from 5.3% over the 12 months prior to the detox episode, until the month of the detox episode when it surged to 17% and then decreased monthly for the next 12 months down to 3.3%. Treatment with concomitant MOUD and residential treatment was especially uncommon before the detox episode at 1%, then increased to almost 3.0% around the time of the detox episode and regressed back to 0.8% (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receipt of treatment for OUD before and after the detox episode - Massachusetts 2012–2014 (n=61,819)

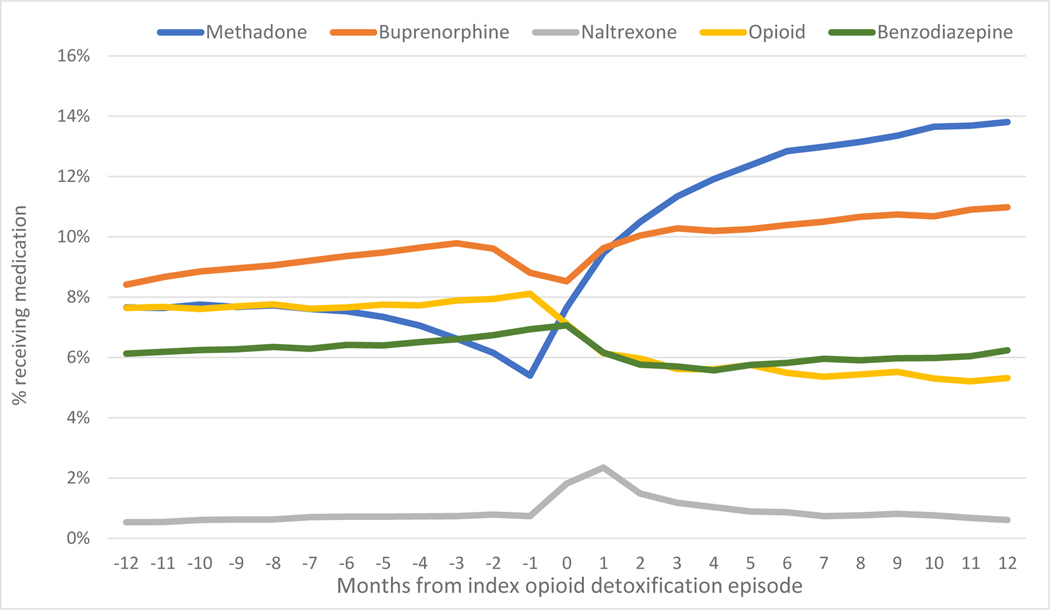

Regarding specific MOUD, methadone treatment frequency decreased before the detox episode from 7.6% to 5.4% and subsequently climbed to 14%. Buprenorphine treatment climbed steadily from 8.4% to 11% across the 12 months before and after detox, with a dip the month before and month of detox. Naltrexone treatment was 0.54% and flat before detox with a bump to 2.4% at the time of detox and then a decreased over the subsequent year. Treatment with opioid pain medication dropped from 8.1% to 5.3%, whereas benzodiazepine remained at 6.1% before and 6.2% after the detox episode. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Receipt of Medication for OUD before and after detox episode - Massachusetts 2012–2014 (n=61,819)

After the detox episode, 41% individuals received any MOUD within 12 months, with buprenorphine being the most common medication (21%). Methadone was the medication with the most median time on treatment at 5 months, and thus the highest cumulative proportion were receiving methadone at 12 months (Figure 3). The median time on naltrexone was one month. The median time in further inpatient treatment was two months for 35% of the cohort. Thirteen percent of the cohort received both MOUD and further inpatient treatment for a median of 5 months. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of detox episodes (n=61,819) followed by medication and/or further inpatient treatment after inpatient detox episode and median months on treatment (not mutually exclusive) – Massachusetts, 2012–2014

| Proportion receiving treatment in at least one month | Median Months on treatment [25th, 75th percentile] | |

|---|---|---|

| Both MOUD and residential* | 13% | 5 [3, 9] |

| Any MOUD | 41% | 3 [1, 8] |

| Methadone | 18% | 5 [2, 10] |

| Buprenorphine | 21% | 3 [1, 6] |

| Naltrexone | 7.2% | 1 [1, 2] |

| Any further residential | 35% | 2 [1, 4] |

MOUD and inpatient at some point 12 months after inpatient detox, not necessarily at the same time.

Mortality, Cumulative Incidence and Adjusted Hazards, On Treatment analyses

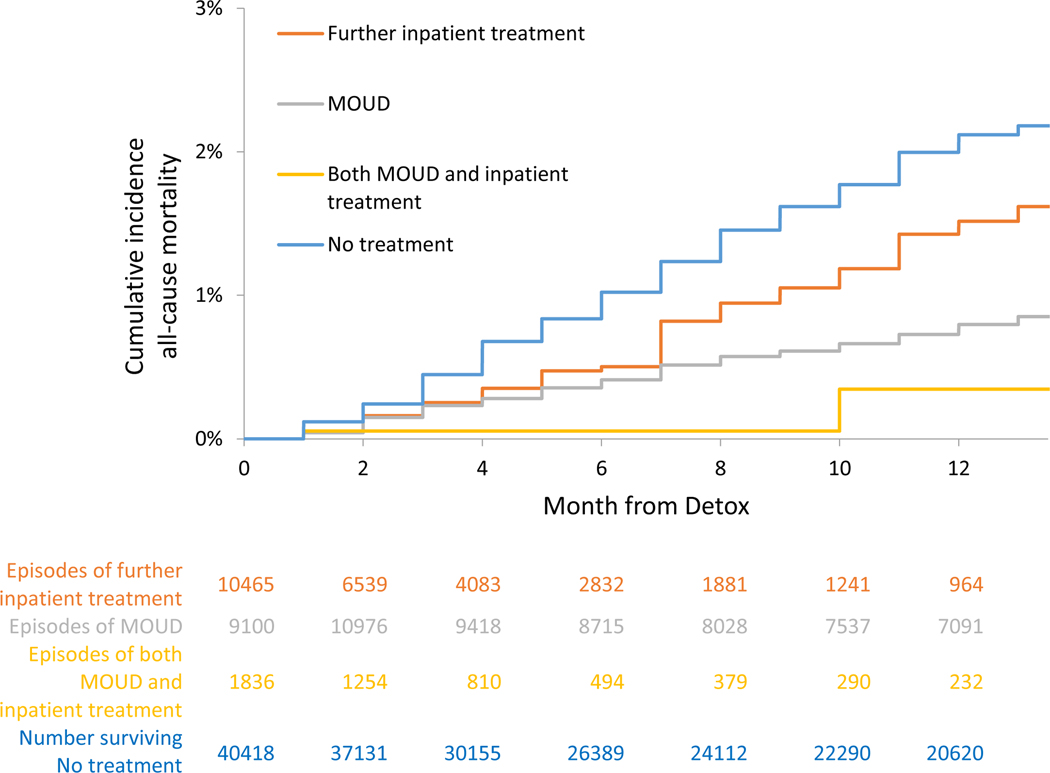

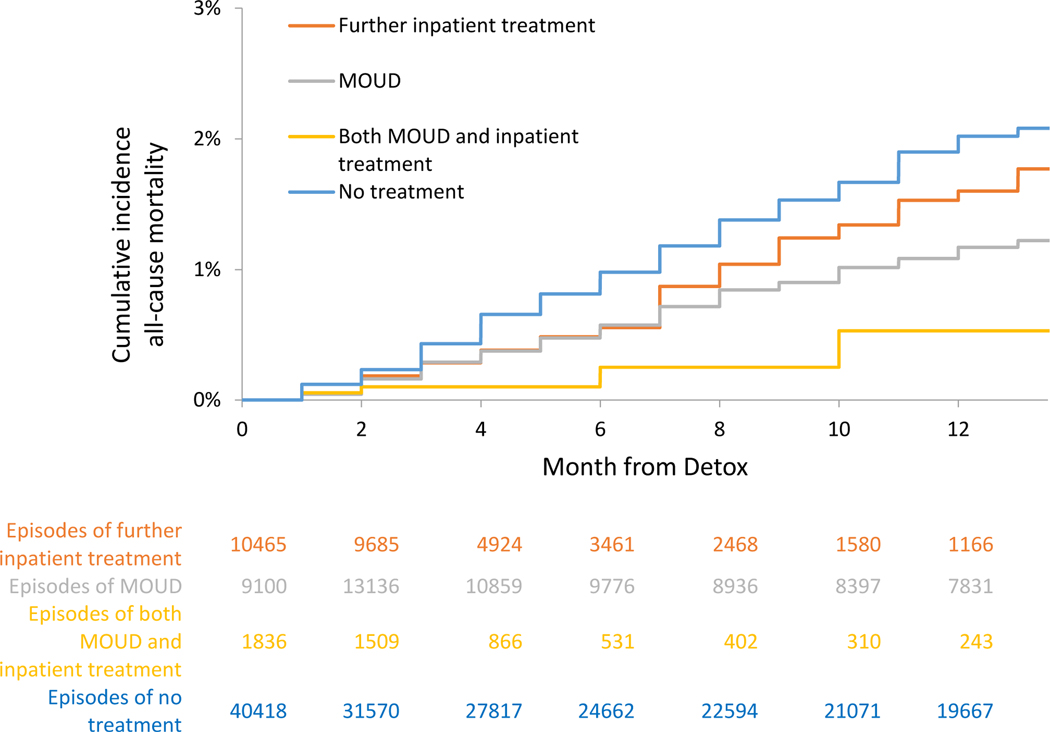

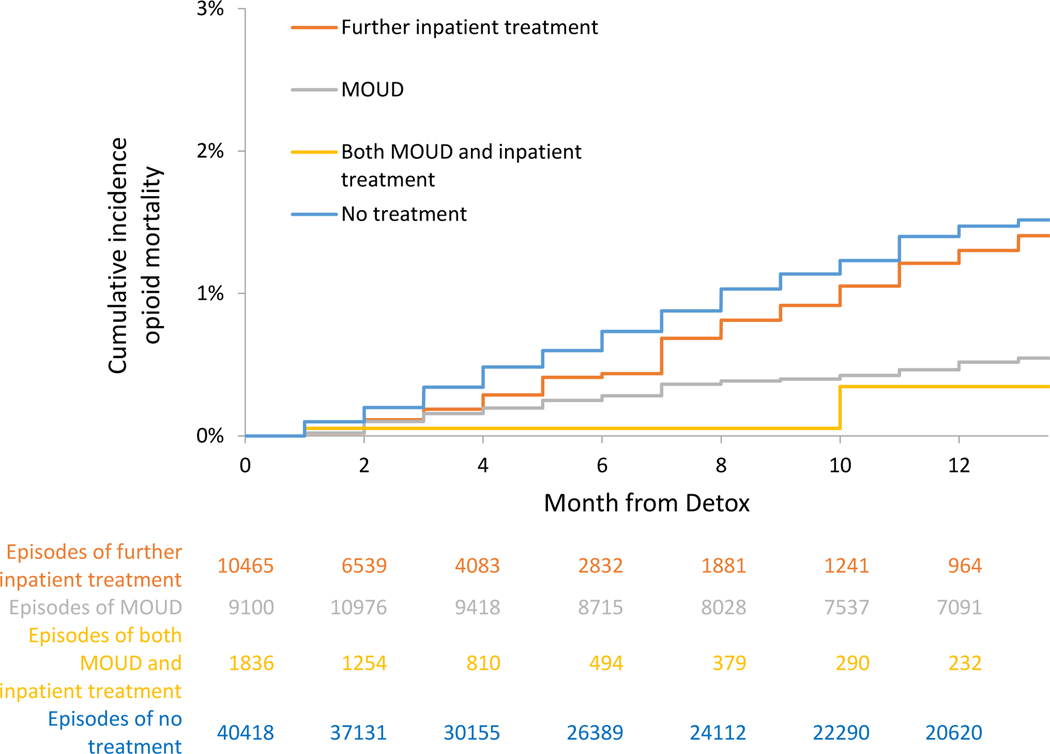

For those receiving no further treatment, the crude mortality rates were 2.04 (95% CI: 1.9–2.2) all-cause deaths per 100 person-years and 1.42 (95% CI: 1.3–1.6) overdose deaths per 100 person-years in the On Treatment analyses. In extended Kaplan-Meier estimator for time-varying exposure to OUD treatment, cumulative incidence for all-cause and opioid mortality at 12 months was lower for time receiving MOUD, further inpatient treatment, or both, than time receiving no treatment (See Figure 4a and 5a and Table 3a). In multivariable Cox proportional hazards models for the On Treatment analyses, all-cause mortality was reduced with MOUD (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR], 0.33 (95% CI: 0.26–0.43), further inpatient (AHR: 0.63 (95% CI: 0.47–0.84)), and combined MOUD and further inpatient (AHR: 0.11 (95% CI: 0.03–0.42)). Opioid mortality was similar with MOUD (AHR: 0.30 (95% CI: 0.22–0.41), further inpatient (AHR: 0.69 (95% CI: 0.50–0.94)), and combined MOUD and further inpatient (AHR: 0.14 (95% CI: 0.03–0.54)). For all-cause mortality, e-value estimates (confidence limit) were 5.51 (4.1), 2.55 (1.7), and 17.67 (4.2) for MOUD, further inpatient treatment and both MOUD and inpatient treatment respectively, with similar results for opioid mortality.

Figure 4a.

Cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality, On Treatment analyses - Massachusetts 2012–2014

Figure 5a.

Cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality, With Discontinuation analysis - Massachusetts 2012–2014

Table 3a.

Crude incidence rates and multivariable Cox proportional hazards analyses for all-cause and opioid-related death by receipt of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and further inpatient addiction treatment, On Treatment – Massachusetts, 2012–2014

| OUD treatment in 12 months following inpatient detox episode* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure Classification – On Treatment† | No treatment | MOUD | Further inpatient treatment | Both MOUD and inpatient treatment |

| Person-years exposure | 30893.5 | 9550.3 | 4254.3 | 815.6 |

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| Number of deaths | 629 | 77 | 54 | ≤10 |

| Crude incidence rate per 100 person-years (95% CI) | 2.04 (1.9,2.2) | 0.81 (0.63,0.99) | 1.27 (0.93,1.6) | ≤1.23 |

| Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡(95% CI) | 1.0 (REF) | 0.34 (0.27,0.43) | 0.63 (0.47,0.84) | 0.11 (0.03,0.43) |

| E-value, estimate (confidence limit)§ | NA | 5.33 (4.08) | 2.66 (1.67) | 17.67 (4.08) |

| Opioid-related mortality | ||||

| Number of deaths | 440 | 50 | 45 | ≤10 |

| Crude mortality rate (95% CI) | 1.42 (1.3,1.6) | 0.52 (0.38,0.67) | 1.06 (0.75,1.4) | ≤1.23 |

| Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡(95% CI) | 1.0 (REF) | 0.31 (0.23,0.41) | 0.69 (0.50,0.94) | 0.14 (0.03,0.55) |

| E-value, estimate (confidence limit)§ | NA | 5.91 (4.31) | 2.26 (1.32) | 13.77 (3.04) |

Index inpatient detox encounter defined as an individual’s first opioid-related inpatient detox encounter between January 2012 and December 2014.

MOUD and inpatient treatment variables are binary time-varying monthly indicators of receipt of treatment. Exposure is limited to months treatment is received.

Results of multivariable cox proportional hazards models adjusting for: age, sex, race/ethnicity, homelessness, anxiety diagnoses, depression diagnoses, opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions, nonfatal overdose episode, release from incarceration, MOUD or residential treatment within 12 months prior to index inpatient detox encounter, and time-varying receipt of opioid prescription, benzodiazepine prescription. (full model results included in Appendix Table 3). All values are adjusted hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

The E-value represents the minimum strength of association between an unmeasured confounder with both the treatment and outcome to explain observed associations between MOUD and mortality. E-values presented for the AHR and 95% confidence limit closest to the null. If the confidence interval includes the null, the E-value is 1.

Data suppressed due to small cell size: <10 indicates a count of 1–9 for that cell. Other cells suppressed to prevent calculation of small cells.

Mortality, Cumulative Incidence and Adjusted Hazards, With Discontinuation analyses

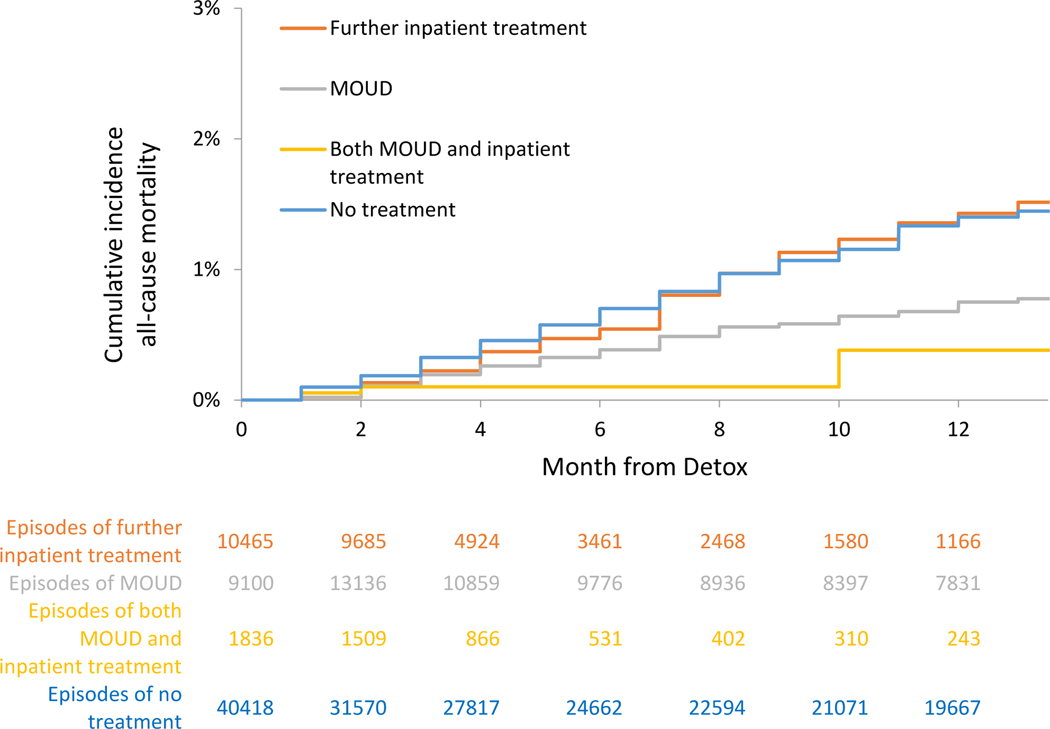

For those receiving no further treatment, the crude mortality rates were 1.94 (95% CI: 1.8–2.1) all-cause deaths per 100 person-years and 1.35 (95% CI: 1.2–1.5) overdose deaths per 100 person-years in with Discontinuation analyses. In extended Kaplan-Meier estimator for time-varying exposure to OUD treatment, cumulative incidence for all-cause and opioid mortality at 12 months was attenuated for receiving MOUD, further inpatient treatment, or both, than time receiving no treatment (See Figure 4b and 5b and Table 3b). In multivariable Cox proportional hazards models for the With Discontinuation analyses, associations were similar. There was a reduction in all-cause mortality with MOUD (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR], 0.51 (95% CI: 0.42–0.62) for MOUD, further inpatient (AHR: 0.76 (95% CI: 0.59–0.96)), and combined MOUD and further inpatient (AHR: 0.20 (95% CI: 0.08–0.55)). Opioid mortality was similar for MOUD (AHR: 0.46 (95% CI: 0.36–0.58) and combined MOUD and further inpatient (AHR: 0.20 (95% CI: 0.06–0.61)). For all-cause mortality, e-value estimates (confidence limit) were 3.33 (2.61), 1.96 (1.25), and 9.47 (3.04) for MOUD, further inpatient treatment and both MOUD and inpatient treatment respectively, with similar results for opioid mortality. For further inpatient and overdose mortality, the hazard ratio was not statistically significant (AHR: 0.84 (95% CI: 0.64–1.10)). (Full models in Supplement Table 3).

Figure 4b.

Cumulative incidence of opioid-related mortality, On Treatment analyses - Massachusetts 2012–2014

Figure 5b.

Cumulative incidence of opioid-related mortality, With Discontinuation analysis - Massachusetts 2012–2014

Table 3b.

Crude incidence rates and multivariable Cox proportional hazards analyses for all-cause and opioid-related death by receipt of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and further inpatient addiction treatment, With Discontinuation – Massachusetts, 2012–2014

| OUD treatment in 12 months following inpatient detox episode* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure Classification – With Discontinuation† | No treatment | MOUD | Further inpatient treatment | Both MOUD and inpatient treatment |

| Person-years exposure | 28527.7 | 10799.2 | 5300.5 | 886.3 |

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| Number of deaths | 553 | 126 | 79 | ≤10 |

| Crude cumulative incidence per 100 person-years (95% CI) | 1.94 (1.80,2.10) | 1.17 (0.96,1.37) | 1.49 (1.16,1.82) | ≤1.13 |

| Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡(95% CI) | 1.0 (REF) | 0.52 (0.42,0.63) | 0.75 (0.59,0.96) | 0.21 (0.08,0.55) |

| E-value, estimate (confidence limit)§ | NA | 3.26 (2.55) | 2.00 (1.25) | 8.99 (3.04) |

| Opioid-related mortality | ||||

| Number of deaths | 386 | 81 | 67 | ≤10 |

| Crude mortality rate (95% CI) | 1.35 (1.22,1.49) | 0.75 (0.59,0.91) | 1.26 (0.96,1.57) | ≤1.23 |

| Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡(95% CI) | 1.0 (REF) | 0.46 (0.36,0.59) | 0.84 (0.64,1.10) | 0.20 (0.06,0.62) |

| E-value, estimate (confidence limit)§ | NA | 3.27 (2.78) | 1.67 (1.43) | 9.47 (2.61) |

Index inpatient detox encounter defined as an individual’s first opioid-related inpatient detox encounter between January 2012 and December 2014.

MOUD and inpatient treatment variables are binary time-varying monthly indicators of receipt of medication. Exposure is extends through the month after treatment discontinuation.

Results of multivariable cox proportional hazards models adjusting for: age, sex, race/ethnicity, baseline anxiety diagnosis, depression diagnosis, opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions in 12 months prior to index inpatient detox encounter, and time-varying receipt of opioid prescription, benzodiazepine prescription. (full model results included in Appendix Table 2a). All values are adjusted hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

The E-value represents the minimum strength of association between an unmeasured confounder with both the treatment and outcome to explain observed associations between MOUD and mortality. E-values presented for the AHR and 95% confidence limit closest to the null. If the confidence interval includes the null, the E-value is 1.

Data suppressed due to small cell size: <10 indicates a count of 1–9 for that cell. Other cells suppressed to prevent calculation of small cells.

Discussion:

Among a population cohort of adults mostly under age 45 and treated for opioid withdrawal in inpatient detox programs, all-cause and opioid mortality were very high in the next twelve months, particularly among those who received no further treatment. Over the subsequent 12 months, 41% of detox patients received an FDA-approved medication for OUD and 35% received any further inpatient treatment. As has been shown in other cohorts, MOUD was strongly associated with 49% or more reduction in all-cause and opioid mortality rates.24,25 Individuals who received further residential treatment had reduced mortality while in that treatment and were treated for a median of 2 months. Few patients received combined treatment with MOUD and inpatient treatment, but when they did, their risk of all-cause and opioid mortality was reduced by 80–90% compared to no treatment.

While our study is unprecedented in its use of a state population cohort that links MOUD, inpatient addiction treatment, and mortality, our findings of high all-cause mortality rates without further treatment of about 2 per 100 person-years are consistent with previous research on detoxification and mortality. A study among 137 detoxification patients in England which found 2.2% (3/137) died of overdose within 4 months after release.14 A study of 10,454 Italian people who inject drugs recruited in treatment found 1 overdose death per 100 person-years overall, but 2.3 overdose deaths per 100 person-years among those in the 30 days after leaving treatment.16 A study that followed 32,322 people in California with opioid dependence initiating either detoxification or maintenance treatment found 0.80 drug-related deaths per 100 person-years among those who left treatment compared to 0.23 drug-related deaths per 100 person-years among those during maintenance treatment.4

People seeking care for opioid withdrawal through inpatient detoxification programs are a high-risk group because of the severity of their opioid use disorder, high risk of opioid relapse, and likely reduced opioid tolerance if MOUD is not initiated or continued. While some transition from detox to further treatment with MOUD or inpatient care, most do not.6,7,26,27 In a Massachusetts study that analyzed addiction treatment episodes between 1996 and 2002, multiple detox admissions without further treatment was the most common utilization pattern among people who injected drugs. 6 Methadone treatment or outpatient counseling after detox was much less common. Our findings of improved survival among high risk individuals who receive MOUD echo similar findings from our study of Massachusetts residents at another healthcare encounter, those who survive an opioid overdose.25 Inpatient detox episodes are high yield health system encounters during which much is to be gained by initiating and engaging patients in evidence-based care. These system encounters are opportunities to mobilize our best treatments and harm reduction efforts for the highest risk individuals. At the patient-provider level, detox programs and their providers have the responsibility to educate their patients and solicit informed consent about the elevated mortality risk when patients do not access further treatment. Overdose education and naloxone rescue kit distribution should be included in every medically managed withdrawal care episode for individuals with OUD. A promising reform would be to convert opioid “detox” programs to programs focused on the initiation and retention on MOUD, where, rather than “opting in” to further treatment, detox patients would have to “opt out” of further treatment. Recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated reduced opioid use among patients initiating buprenorphine or naltrexone during initial inpatient opioid use disorder treatments.22,23 The survival benefits of MOUD are limited to the time retained on MOUD.16,24,25 Thus, intervention development should focus on both how to initiate detox patients on MOUD and how to increase retention on MOUD.

In this cohort, median duration of residential treatment was shorter than MOUD and associated with less reduction in mortality than MOUD, but when combined with MOUD, the reduction in risk may be synergistically reduced. Therefore, for high-risk individuals for whom MOUD is not sufficient treatment, combining it with further residential is warranted. Individuals who are neither interested in nor have access to MOUD likely benefit from further residential while participating, but residential treatment is time limited. Thus, overall overdose morality risk reduction from further residential treatment alone may be marginal; discontinuation analyses for opioid mortality did not achieve statistical significance.

Factors other than OUD treatment were included in the mortality models to reduce confounding (Supplement Table 3). As expected, younger age was associated with reduced hazard of all-cause mortality, but it was also associated with reduced hazard of overdose mortality. Previous treatment with methadone maintenance, baseline anxiety or depression diagnoses, and prescriptions for opioids for pain and benzodiazepines either before or after the index detox episode were associated with either increased overdose mortality or both overdose and all-cause mortality. Previous non-fatal overdose and incarceration were both associated with increased mortality. Concomitant mental illness and exposure to prescription opioids and benzodiazepines are known risks for overdose and indicators of worse overall health and thus higher all-cause mortality. However, pre-detox episode methadone maintenance may mark a special group of individuals who are either recently discharged from MMT or being treated with methadone, but not doing well.

Detox patients who are homeless may be especially likely to benefit from further inpatient treatment. Individuals who are homeless are at high risk of overdose mortality.34 Homelessness is more common among residential treatment patients than outpatient treatment patients.35 Detox patients who are homeless have a stronger preference for further inpatient care than non-homeless patients.9 Among detox patients, persistent homelessness is a strong risk factor for subsequent mortality.36 However, in our models homelessness was unexpectedly associated with lower all-cause and overdose mortality in the adjusted models. Our measure of homelessness was specific, with face validity, but it did not distinguish chronic from acute homelessness, and we could not analyze it as a time-varying exposure variable. More study is warranted in a cohort with more detail about homelessness to understand the interplay between homelessness, MOUD, inpatient treatment and mortality among people with OUD.

Our analyses had strengths and limitations. We employed a first of its kind dataset that drew from the almost complete population of one state with universal healthcare coverage. The dataset individually linked multiple statewide databases allowing for the identification of the state population cohort with inpatient opioid detoxification treatment, the tracking of exposures before and after treatment episodes and the determination of opioid overdose and all-cause mortality. A limitation in any observational study is the potential for confounding, and in particular confounding by indication where individuals that receive different treatment modalities have inherent differences in their risk for the outcome. We controlled for several known confounders, including demographic, medical, mental health, and addiction treatment variables, but the potential for unmeasured confounding persists. Calculated E-values were 3 or greater for the MOUD treatment exposures and about 2 or greater for the residential treatment exposures, indicating that unmeasured confounders would need to be highly associated with the exposure and outcome to account for these findings. We also note the potential for misclassification bias with exposures and outcomes. Only treatment episodes reported by state-licensed and contracted treatment facilities were included. While these facilities likely include a majority of detox and residential treatment programs in Massachusetts, some programs might have not been included. Further work is needed to clarify how many programs or treatment episodes were not captured in our data. Missing episodes of detox would have resulted in fewer individuals being included in the study. Missing residential treatment would have resulted in some individuals being misclassified as not receiving residential treatment when they did, which would likely have resulted in biasing results towards the null hypothesis. Methadone treatment classification also relied on this BSAS data, but we bolstered the methadone data by crossing and merging it with APCD data for methadone. Buprenorphine from the PMP and naltrexone from the APCD were complete because they represent prescription filling at the dispensing pharmacy. Because methadone, naltrexone, and residential treatment exposure was only measurable at the month level, analyses were conducted using monthly exposure, rather than daily exposure. Finally, claims for naltrexone in this dataset did not distinguish between oral and injectable naltrexone, so we were not able to analyze these formulations separately.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrated that among a state population cohort of individuals treated with inpatient opioid detox, the mortality rate was high. Treatment with MOUD or further inpatient care was accessed by fewer than half, rarely combined, and typically not sustained. Those who were treated with MOUD or further residential treatment had better survival while receiving those treatments. Our best understanding of the evidence is that patients treated in inpatient detox should not be “detoxed,” but should be started on an MOUD that they are likely to continue and connected with further residential treatment. The combination of MOUD and residential may be particularly protective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge Ryan Bernstein for his data management work on earlier aspects of this study and Mary Tomanovich for formatting the manuscript. We acknowledge the Massachusetts Department of Public Health for creating the unique, cross-sector database used for this project and for providing technical support for the analysis.

Funding support: By grant 1UL1TR001430 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Larochelle was supported by award K23 DA042168 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and a Boston University School of Medicine Department of Medicine Career Investment Award. By Office of National Drug Control Policy’s Combatting Opioid Overdose through Community-level Intervention grant program through a subcontract with University of Baltimore (G1799ONDCP06B).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interests: Not applicable

Clinical trial registration: Not applicable

References:

- 1.Scholl L, Seth P, Mbabazi K, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019. January 4;67(5152):1419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hser Y-I, Mooney LJ, Saxon AJ, Miotto K, Bell DS, Zhu Y, et al. High Mortality Among Patients With Opioid Use Disorder in a Large Healthcare System. J Addict Med. 2017. August;11(4):315–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B, Briegleb C, Ali H, Hickman M, et al. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction. 2011. January;106(1):32–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans E, Li L, Min J, Huang D, Urada D, Liu L, et al. Mortality among individuals accessing pharmacological treatment for opioid dependence in California, 2006–10. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2015. June;110(6):996–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mee-Lee D, Shulman GD, Fishman MJ, Gastfriend D, Miller MM, Provence SM. The ASAM Criteria: Treatment Criteria for Addictive, Substance-Related, and Co-Occuring Conditions [Internet]. The Change Companies; 2013. [cited 2019 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.americanhealthholding.com/Content/Pdfs/asam%20criteria.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundgren LM, Sullivan L, Amodeo M. How do treatment repeaters use the drug treatment system? An analysis of injection drug users in Massachusetts. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006. March;30(2):121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mark TL, Vandivort-Warren R, Montejano LB. Factors affecting detoxification readmission: analysis of public sector data from three states. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006. December;31(4):439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spear SE. Reducing Readmissions to Detoxification: An Interorganizational Network Perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014. April 1;137:76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein MD, Anderson BJ, Bailey GL. Preferences for Aftercare Among Persons Seeking Short-Term Opioid Detoxification. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015. December;59:99–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein MD, Flori JN, Risi MM, Conti MT, Anderson BJ, Bailey GL. Overdose history is associated with postdetoxification treatment preference for persons with opioid use disorder. Subst Abuse. 2017. December;38(4):389–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins ED, Kleber HD, Whittington RA, Heitler NE. Anesthesia-assisted vs buprenorphine- or clonidine-assisted heroin detoxification and naltrexone induction: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005. August 24;294(8):903–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smyth BP, Barry J, Keenan E, Ducray K. Lapse and relapse following inpatient treatment of opiate dependence. Ir Med J. 2010. June;103(6):176–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey GL, Herman DS, Stein MD. Perceived relapse risk and desire for medication assisted treatment among persons seeking inpatient opiate detoxification. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013. September;45(3):302–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strang J, McCambridge J, Best D, Beswick T, Bearn J, Rees S, et al. Loss of tolerance and overdose mortality after inpatient opiate detoxification: follow up study. BMJ. 2003. May 3;326:959–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wines JD, Saitz R, Horton NJ, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Samet JH. Overdose after detoxification: a prospective study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007. July 10;89(2–3):161–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davoli M, Bargagli AM, Perucci CA, Schifano P, Belleudi V, Hickman M, et al. Risk of fatal overdose during and after specialist drug treatment: the VEdeTTE study, a national multi-site prospective cohort study. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2007. Dec;102(12):1954–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravndal E, Amundsen EJ. Mortality among drug users after discharge from inpatient treatment: an 8-year prospective study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010. April 1;108(1–2):65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walley AY, Cheng DM, Quinn EK, Blokhina E, Gnatienko N, Chaisson CE, et al. Fatal and non-fatal overdose after narcology hospital discharge among Russians living with HIV/AIDS who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;39:114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larochelle MR, Bernstein R, Bernson D, Land T, Stopka TJ, Rose AJ, Bharel M, Liebschutz JM, Walley AY. Touchpoints–Opportunities to predict and prevent opioid overdose: A cohort study. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2019. November 1;204:107537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD002207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD002209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JD, Nunes EV, Novo P, Bachrach K, Bailey GL, Bhatt S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2018. January 27;391(10118):309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanum L, Solli KK, Latif Z-E-H, Benth JŠ, Opheim A, Sharma-Haase K, et al. Effectiveness of Injectable Extended-Release Naltrexone vs Daily Buprenorphine-Naloxone for Opioid Dependence: A Randomized Clinical Noninferiority Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017. 01;74(12):1197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017. April 26;357:j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, Stopka TJ, Wang N, Xuan Z, et al. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder After Nonfatal Opioid Overdose and Association With Mortality: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2018. August 7;169(3):137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reif S, Acevedo A, Garnick DW, Fullerton CA. Reducing Behavioral Health Inpatient Readmissions for People With Substance Use Disorders: Do Follow-Up Services Matter? Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2017. August 1;68(8):810–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu H, Wu L-T. National trends and characteristics of inpatient detoxification for drug use disorders in the United States. BMC Public Health. 2018. August 29;18(1):1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massachusetts Department of Public Health. An Assessment of Fatal and Nonfatal Opioid Overdoses in Massachusetts (2011–2015) [Internet]. 2017. Aug. Available from: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/08/31/legislative-report-chapter-55-aug-2017.pdf

- 29.Wu L-T, Zhu H, Swartz MS. Treatment utilization among persons with opioid use disorder in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016. December 1;169:117–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snapinn SM, Jiang QI, Iglewicz B. Illustrating the impact of a time-varying covariate with an extended Kaplan-Meier estimator. The American Statistician. 2005. November 1;59(4):301–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amorim LD, Cai J. Modelling recurrent events: a tutorial for analysis in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2015. February 1;44(1):324–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trujols J, Guàrdia J, Peró M, Freixa M, Siñol N, Tejero A, de los Cobos JP. Multi-episode survival analysis: an application modelling readmission rates of heroin dependents at an inpatient detoxification unit. Addictive behaviors. 2007. October 1;32(10):2391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med. 2017. August 15;167(4):268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baggett TP, Hwang SW, O’Connell JJ, Porneala BC, Stringfellow EJ, Orav EJ, et al. Mortality Among Homeless Adults in Boston: Shifts in Causes of Death Over a 15-year Period. JAMA Intern Med. 2013. February 11;173(3):189–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarty D, Fuller B, Kaskutas LA, Wendt WW, Nunes EV, Miller M, et al. Treatment programs in the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008. January 1;92(1–3):200–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saitz R, Gaeta J, Cheng DM, Richardson JM, Larson MJ, Samet JH. Risk of mortality during four years after substance detoxification in urban adults. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2007. March;84(2):272–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.