Abstract

For natural transformation to occur, bacterial cells must first develop a programmed physiological state called competence. Competence in Bacillus subtilis, which occurs only in a fraction of cells, is a transient stress response that allows cells to take up DNA from the environment. During natural chromosomal transformation, the internalized linear single-stranded (ss) DNA recombines with the identical (homologous) or partially identical (homeologous) sequence of the resident duplex. The length of the integrated DNA, which can be measured, depends on the percentage of sequence divergence between the donor (internalized) and the recipient (chromosomal) DNAs.

The following protocol describes how to induce the development of competence in B. subtilis cells, how to transform them with donor DNAs representing different percentages of sequence divergence compared with the recipient chromosomal DNA, how to calculate the chromosomal transformation efficiency for each of them, and how to amplify the chromosomal DNA from the transformants in order to measure the length in base pairs (bp) of the integrated donor DNA.

Keywords: Natural chromosomal transformation, Bacillus subtilis competent cells , Divergent DNA sequences, Integration length

Background

Natural transformation is a bacterial programmed mechanism mediated by natural competence systems encoded in the genomes of many bacteria (Chen and Dubnau, 2004; Chen et al., 2005 ; Takeuchi et al., 2014 ; Johnston et al., 2014 ). Competence development allows cells to take up DNA from the environment (Chen and Dubnau, 2004; Chen et al., 2005 ; Thomas and Nielsen, 2005; Kidane et al., 2012 ; Yadav et al., 2012 ; Yadav et al., 2013 ; Takeuchi et al., 2014 ; Johnston et al., 2014 ).

In Bacillus subtilis transient natural competence is induced in a subset of cells by starving them of critical nutrients ( Kidane et al., 2012 ; Chen and Dubnau, 2004). In the competent subpopulation, DNA replication is halted, expression of a set of genes is induced, and the DNA uptake apparatus is built at one cell pole (Chen and Dubnau, 2004; Kidane et al., 2012 ). The DNA uptake apparatus binds environmental double-stranded (ds) DNA, degrades one of the strands, transports the other strand (independently of its nucleotide sequence and polarity) through the cell wall and the membrane into the cytosol. During chromosomal transformation, the incoming single-stranded (ss) DNA is integrated into the recipient dsDNA replacing homologous (or partially homologous) chromosomal sequences ( Kidane et al., 2012 ).

It has been already shown that the divergence between the sequences of the internalized and the recipient DNAs, provides a barrier to chromosomal transformation and decreases the length of integration of donor DNA ( Carrasco et al., 2016 ; Carrasco et al., 2019 ).

In this protocol, we describe how to transform B. subtilis competent cells to finally measure the length of the integrated DNA. The experimental procedure described here to prepare B. subtilis competent cells is an adaptation of the previous described by Dubnau et al., 1973 and Alonso et al., 1988 .

Materials and Reagents

Petri dishes 90 mm (VWR, catalog number: 391-0440)

Sterile wood toothpicks

Sterile pipette tips

50- and 100-ml Flasks (Duran, catalog numbers: 21-216-17 and 21-216-24, respectively)

1.5- and 2-ml tubes (Sarstedt, catalog number: 72.690.001; Fisherbrand, catalog number: 11393613)

Polystyrol/Polystyrene cuvettes 10 x 4 x 45 mm (SARSTEDT, catalog number: 67742)

Semi-log paper

Glass beads 3 mm (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: Z143928-1EA)

Bacillus subtilis cells (wild-type strain [B. subtilis 168] or derivative deletion mutants)

-

Primers (Sigma-Aldrich)

Forward primer: 5′-CATATAATACGCATGATTTGAGGGG

Reverse primer: 5′-GTCCGTCGTAAAGCACTGTTTTG

-

Plasmids: pCB980; pCB981; pCB982; pCB983; pCB984; pCB1054; pCB985; pCB1056

Note: These plasmids have been previously reported in Carrasco et al., 2016 and Carrasco et al., 2019.

Escherichia coli 2,710-bp pUC57 vector

Bi-distilled H2O (ddH2O)

Glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: G6279-4L)

Rifampicin (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: 13292-46-1)

Ampicillin sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: 69-52-3)

Plasmid purification kit (Qiagen plasmid mini kit, catalog number: 27106)

Bacto tryptone pancreatic digest of casein (BD Biosciences, catalog number: 211705)

Bacto yeast extract (Extract of autolyzed yeast cells) (BD Biosciences, catalog number: 211750)

European bacteriological agar (Pronadisa, catalog number: 1800)

NaCl (VWR, catalog number: 7647-14-5)

Agarose D1 medium EEO (Pronadisa, catalog number: 8021)

PCR purification kit (Speedtools PCR clean up kit, Biotools, catalog number: 740609.50.205571)

Na2HPO4 (Calbiochem, Merck, catalog number: 7558-79-4)

KH2PO4 (Calbiochem, Merck, catalog number: 7778-77-0)

K2HPO4 (Calbiochem, Merck, catalog number: 16788-57-1)

D-(+)-Glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: 50-99-7)

Tri-Sodium citrate dihydrate (Na3C6O7·2H2O) (Merck, catalog number: 6132-04-3)

Ammonium sulfate (MP Biomedical, catalog number: 7783-20-2)

Titriplex III (EDTA) (Merck, catalog number: 6381-92-6)

Acetic acid glacial (AppliChem PanReac, catalog number: 141008.1214)

Casein hydrolysate (EMD, catalog number: 65072-00-6)

CaCl2·2H2O (Merck, catalog number: 10035-04-8)

MgSO4·7H2O (Merck, catalog number: 10034-99-8)

Tryptophan (Merck, catalog number: 54-12-6)

Methionine (Merck, catalog number: 63-68-3)

Tris-HCl (AppliChem PanReac, catalog number: A1086)

1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 (see Recipes)

Luria Bertani (LB) broth (see Recipes)

LB-agar (see Recipes)

GM1 (see Recipes)

GM2 (see Recipes)

SBase10x (see Recipes)

TAE 50x (see Recipes)

Equipment

Pipettes

30 and 37 °C incubators

Amersham Biosciences Ultrospec 3100 Pro UV/Visible Spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare)

Heating block

Microcentrifuge

Thermal cycler (VWR, Doppio, catalog number: 732-2551)

NanoDropTM 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

Autoclave

-80 °C freezer

Software

-

Sequence data compilation

Sequences of rpoB genes from different Bacillus species or subspecies need to be downloaded from relevant databases. A recommended database is NCBI. A single C to T transition mutation at codon 482 (position 1,446) in the house-keeping rpoB gene, confers resistance to rifampicin (RifR). To generate the rpoB482 sequence variants, a C to T change is required at the position 1,446 of each sequence (see Figure 1A, asterisk).

Online tool (BLAST) to perform the nucleotide alignment

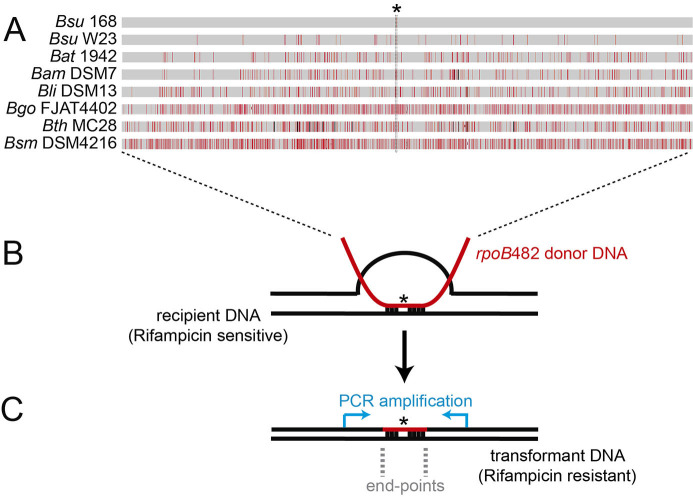

Figure 1. Bacillus subtilis natural chromosomal transformation and detection of mean integration.

A. Distribution of sequence divergence among different Bacillus species. A single C-to-T transition mutation at codon 482 (indicated with an asterisk) in the essential rpoB gene renders the rpoB482 gene, which confers rifampicin-resistant (RifR). The rpoB482 DNA was derived from B. subtilis 168 (Bsu 168), B. subtilis W23 (Bsu W23), B. atrophaeus 1942 (Bat 1942), B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7 (Bam DSM7), B. licheniformis DSM13 (Bli DSM13), B. gobiensis FJAT-4402 (Bgo FJAT4402), B. thuringiensis MC28 (Bth MC28) and B. smithii DSM4512 (Bsm DSM4216). Mismatches between RifR donor and the corresponding rpoB in the rifampicin sensitive recipient strain are indicated by vertical red bars, and insertions/deletions by vertical black bars. Bar thickness represents the number of mismatches in a particular area. B. Chromosomal transformation. RecA-mediated homeologous recombination between the rpoB482 donor DNAs (in red) and the recipient rpoB gene (in black). C. Measurement of the length of the integrated donor DNA into the recipient. PCR amplification of the RifR transformants using DNA primers hybridizing upstream and downstream the rpoB gene (blue arrows). The mean length detection between the first predicted and the first observed mismatch define the end-points region.

Procedure

-

Preparation of Bacillus subtilis competent cells

Streak B. subtilis cells onto LB-agar plate.

Incubate the plate at 37 °C overnight (O/N) or room temperature (RT) for 2-3 days.

Using a sterile toothpick of wood, inoculate 5 ml of GM1 with a single colony from the O/N plate in a 50-ml flask and incubate the culture O/N without aeration at 30 °C.

Dilute the overgrown culture in 15 ml of GM1 to reach an OD560 of 0.05.

Divide the culture into two parts: 100-ml flask containing 10 ml of culture to measure the OD560 and 50-ml flask containing 5 ml to freeze the cells. The division of the culture in two flasks is recommended to avoid the contamination of the culture that it will be frozen. The possible contamination might occur due to the multiple OD560 measurements.

Incubate the cultures at 37 °C in an incubator for flasks at 250 rpm. Two hours later start measurements (from the 100-ml flask for measurements) at OD560 every 30 min. Plot the data in a semi-log paper to predict the point of inflection between the exponential phase of growth and the stationary phase (OD560 of approximately 1).

-

One hour after having reached the point of inflection in the growth curve, cells have become competent. At this point, there are two options (always use the 5 ml culture from the 50-ml flask that does not stop shaking): transform the cells (see Step B3) or freeze the cells to use them else when. To freeze the cells, add glycerol (20% final concentration) and, as soon as possible, divide the culture into 1 ml aliquots in 2-ml tubes and put them on dry ice. Keep the tubes at -80 °C.

Note: This section of the protocol is an adaptation of the previously described methods by Dubnau et al., 1973 and Alonso et al., 1988.

-

Bacillus subtilis chromosomal transformation (see Figure 1B)

Add the frozen cells (1 ml) into 10 ml GM2 medium (see Recipes) in a 100-ml flask.

Incubate the culture for 1.5-2 h at 37 °C with shaking speed as aforementioned.

-

Transfer 1 ml of competent cells to 2-ml tubes:

Incubate the tubes at 37 °C for 1 h with shaking in a heating block at 250 rpm.

-

Serial dilutions and plating.

Note: Depending on the rpoB482 DNAs (see Table 1) and the mutant competent cells used, preliminary experiments should be performed to determine the range of dilutions required for plating.

For plating the total number of cells, create 1:10 serial dilutions of the “Tube (-)” (negative control without DNA, see Step B3a) to a 10-5 dilution in LB, and plate 100 μl of desired dilutions onto LB-agar plates using glass beads.

-

For plating the transformants (see Figure 1C), create 1:10 serial dilutions of the “Tube (+)” (with DNA, see Step B3b) to a 10-2 dilution in LB and plate 100 μl of desired dilutions onto LB-agar plates supplemented with rifampicin (8 μg/ml) using glass beads.

Note: When the chromosomal transformation efficiency is impaired, 100 and 101 dilutions could be necessary. In this case, harvest cells by centrifugation for 3 min at 900 × g at room temperature (RT). There should be a visible pellet at the bottom of the microfuge tube. Resuspend cells in 100 μl LB and plate the whole volume onto LB-agar plates supplemented with rifampicin (8 μg/ml) using glass beads.

For plating the spontaneous rifampicin resistant (RifR) cells, plate the “Tube (-)” (negative control without DNA, see Step B3a) at the same dilution as the most concentrated dilution of transformants (see Step B5b) onto LB-agar plates supplemented with rifampicin (8 μg/ml) using glass beads.

Incubate plates at 37 °C overnight, or leave at RT for 2-3 days.

-

Count colonies on the most appropriate plate (the one that contains around 100-1000 colonies). The colonies on each plate must be multiplied by their dilution factor to obtain colony forming units (CFUs)/ml.

Note: In order to reduce the variability between different experiments, count 100-500 CFUs per plate from the proper dilution.

-

PCR amplification of rpoB482 DNA from the RifR transformants (see Figure 1C)

-

Lyse the transformant cells

-

Pick up a single colony with a sterile toothpick and insert it into a 1.5 ml tube containing 20 μl ddH2O and incubate the tube for 5 min at 95 °C.

Note: It is necessary to amplify by PCR and send for sequencing several examples (several single colonies) resulted from the transformation with each DNA. This is because the recombination point can vary (from one to another) so that the end points and the length of integration also varies. Finally, we determine the length of integration as the average of lengths from different examples of each condition.

Centrifuge for 5 min at 20,000 × g at RT.

Use 2 μl of supernatant per PCR reaction as DNA template.

-

-

Perform a PCR 20 μl per reaction.

-

Set up the PCR, by adding the following component into a PCR tube on ice:

DNase-free ddH2O 11.5 μl

dNTP mix (2.5 μM each) 2 μl

Forward primer (10 μM) (see Table 2) 2 μl

Reverse primer (10 μM) (see Table 2) 1 μl

PCR buffer (10x) 2 μl

Taq DNA polymerase (250 Units) 2 μl

Supernatant lysates (DNA template) 2 μl

-

Run PCR:

1 cycle 94 °C, 10 min

30 cycles 94 °C, 1 min; 55 °C, 1 min and 30 s; 72 °C, 2 min and 45 s

1 cycle 72 °C, 10 min

Load 2 μl of PCR products on a 0.8% agarose gel in 1x TAE stained with EtBr. Run the gel in 1x TAE buffer at 5 to 8 V/Cm for 1 h at RT (bands expected of 2,997 bp). Visualize the gel under UV light.

Purify the PCR products using the PCR purification kit (see Materials and Reagents).

-

-

-

Sequencing

Send for sequencing each PCR product mixed with Forward and/or Reverse primer (see Table 2) (following the instructions of the company).

-

Computational analysis

Run two different nucleotide BLASTs:

-

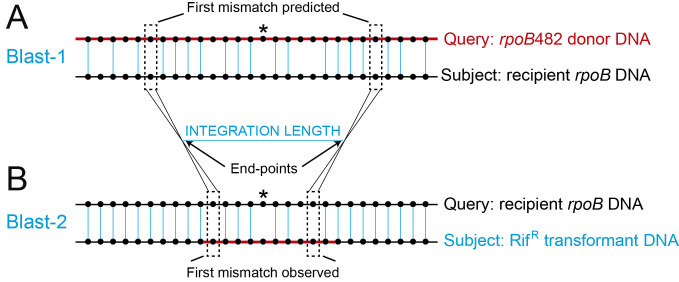

BLAST-1 (see Figure 2A): to visualize the bases that are not aligned (defined here as mismatches) between the RifR donor DNAs (see Table 1) and the corresponding rpoB in the rifampicin sensitive recipient strain, run a nucleotide BLAST using each of the rpoB482 variants sequences (donor DNAs) (see Table 1) as query sequence against the house-keeping rpoB gene sequence (recipient DNA) as subject sequence.

Note: The presence or the absence of the mismatches between the donor and the recipient DNA will be used to determine the overall integration length.

BLAST-2 (see Figure 2B): to visualize the bases from the RifR transformants with donor DNA origin, run a nucleotide BLAST using the house-keeping rpoB gene sequence (recipient DNA) as query sequence against each of the RifR transformants sequences (see Procedure D) as subject sequences.

-

Table 1. Plasmid-borne rpoB482 variants from different Bacillus species or subspecies cloned into E. coli pUC57 vector.

The house-keeping rpoB gene encodes the essential β subunit of RNA polymerase. A single C to T transition at codon 482 (position 1446) in the rpoB gene confers resistance to rifampicin (RifR) (Nicholson and Maughan, 2002). This mutation was introduced in the rpoB region of the indicated Bacillus species or subspecies leading to the rpoB482 mutant variants for selection of the RifR transformants (see Figure 1A). Homologous regions at 5′- and 3′-ends of the different rpoB482 genes were selected to eliminate variants in the PCR amplification efficiencies. The 2,997-bp segment of the different rpoB482 genes was in vitro synthesized and cloned into Escherichia coli 2,710-bp pUC57 vector (Ampicillin resistance). The accuracy of the in vitro synthesized DNAs was confirmed by nucleotide sequence (GeneWiz, London, UK).

| Plasmid name | Origin of Bacillus DNAs | Number of mismatches |

Donor-recipient sequence divergence (in %) |

| pCB980 | B. subtilis 168 | 1 | 0.03 |

| pCB981 | B. subtilis W23 | 74 | 2.47 |

| pCB982 | B. atrophaeus 1942 | 250 | 8.35 |

| pCB983 | B. amyloliquefaciens DSM7 | 303 | 10.12 |

| pCB984 | B. licheniformis DSM13 | 435 | 14.52 |

| pCB1054 | B. gobiensis FJAT4402 | 510 | 17.0 |

| pCB985 | B. thuringiensis MC28 | 624 | 20.83 |

| pCB1056 | B. smithii DSM4216 | 681 | 22.74 |

Table 2. Primers.

These primers hybridize with the region upstream and downstream of the 2,997-bp rpoB482 DNAs. These primers are used in this protocol for amplifying and sequencing rpoB482 genes from the RifR transformants.

| Primers | Sequences (5′-) |

|---|---|

| Forward primer | CATATAATACGCATGATTTGAGGGG |

| Reverse primer | GTCCGTCGTAAAGCACTGTTTTG |

Figure 2. Analysis of the integrated sequences and measurement of the integration length.

A. Schematic representation of the BLAST-1 using rpoB482 donor DNA (with different Bacillus origins) (red line) as query sequence against the house-keeping rpoB gene sequence (recipient DNA) (black line) as subject sequence. Black dotted lines indicate the “First mismatches predicted”. B. Schematic representation of the BLAST-2 using the house-keeping rpoB gene sequence (recipient DNA) (black line) as query sequence against the PCR product got from the RifR transformants DNA (blue line) as subject. Black dotted lines indicated the “First mismatches observed”. End-points are defined as the average region between the first predicted and first observed mismatches and represent the recombination points. The integration length is calculated as the subtraction between both end-points. Black dots represent DNA bases and blue vertical lines represent the bases that are aligned between both sequences. The mutation that confers resistant to rifampicin is represented with an asterisk.

Data analysis

-

Chromosomal transformation efficiency

Colonies on each plate must be multiplied by their dilution factor to obtain CFUs/ml (see “Step B5e”). For data analysis, transformation efficiency is calculated using the formula: Chromosomal transformation efficiency = T-E/Nf, where “T” corresponds to the transformants (see Step B5b), “E” corresponds to the spontaneous RifR cells (see Step B5c) and “Nf” is the total number of cells (see “Step B5e”).

-

Analysis of the integrated sequences

Go to the resulting BLAST-2 (see Step E2 and Figure 2B) and visualize the fragment of donor DNA that is integrated into the recipient DNA by transformation (see Figures 1C and 2B).

-

Go to the resulting BLAST-2 (see Step E2 and Figure 2B) and search for the first mismatch between the query (recipient DNA) and the subject (RifR transformant DNA) sequences, to identify the “First mismatch observed”.

Note: The bases aligned between these two sequences correspond to the part of the recipient DNA, whereas the mismatches represent the bases with donor origin in the RifR transformant sequence.

-

Map of integration end-points

We define end-points as the borders of the donor DNA sequence integrated into the recipient DNA.

Knowing the position of the “First mismatch observed” (see Data analysis B), go to that position in the resulting BLAST-1 (see Step E1 and Figure 2A) and search upstream into the sequence, the first mismatch between the query sequence (recipient DNA) and the subject sequence of interest (depending on the donor DNA used) to identify the “First mismatch predicted”.

-

Calculate the end-point using the formula: end-point= Fp-Fo/2, where “Fp” corresponds to the “First mismatch predicted” and “Fo” corresponds to the “First mismatch observed”.

Note: We assume that the recombination events have occurred between the end-points at the borders of the donor DNA sequence integrated into the recipient one. It is necessary to identify the “First predicted” and the “First observed” mismatches from both borders for determining the two end-points (see Figure 2).

-

Determination of the integration length

Calculate the integration length as the subtraction between both end-points (see Figure 2).

Recipes

-

1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5

Dilute 121.1 g Tris in 1 L of ultrapure water and adjust pH to 7.4 with HCl

-

Luria Bertani (LB) broth

10 g/L Bacto tryptone

5 g/L Bacto yeast extract

10 g/L NaCl

Sterilize by autoclaving

-

LB-agar

LB medium

12 g/L Agar

Sterilize by autoclaving

-

GM1 (Table 3)

Note: Filter the GM1 medium using vacuum filtration and store at 4 °C.

Table 3. GM1 medium recipe.

Compound Amount Final concentration SBase 10x 10 ml 1x Glucose 10% 5 ml 0.5 % Yeast extract 2% 5 ml 0.1 % Casein hydrolysate 2% 2 ml 0.02 % MgSO4 1 M 80 μl 0.8 mM D/L tryptophan 1.25 mg/ml 2 ml 0.025 % L-Methionine 10 mg/ml 200 μl 0.02 % ddH2O top up to 100 ml -

GM2 (Table 4)

Note: GM2 medium should be prepared before use.

Table 4. GM2 medium recipe.

Compound Amount Final concentration GM1 medium 10 ml MgSO4 1 M 33 μl 3.3 mM CaCl2 0.5 M 10μμl 0.5 mM -

SBase 10x (Table 5)

Table 5. SBase 10x recipe.

Compound Amount Final concentration Ammonium sulfate 20 g 150 mM K2HPO4 140 g 610 mM KH2PO4 60 g 440 mM Sodium citrate 10 g 34 mM -

TAE 50x (Table 6)

Table 6. TAE 50x recipe and preparation.

Compound Amount Final concentration Tris-HCl 121 g 1 M Acetic acid glacial 28.5 ml Titriplex III 18.6 g 50 mM ddH2O top up toSterilize by autoclaving1 L

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MICINN)/ FEDER PGC2018-097054-B-I00 to J. C. Alonso. ES thanks MINECO (BES-2013-063433) for the fellowship and B.C thanks Programa Centros de Excelencia Severo Ocho-CNB for fellowship.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest or competing interests with respect to this work.

Citation

Readers should cite both the Bio-protocol article and the original research article where this protocol was used.

References

- 1. Alonso J. C., Tailor R. H. and Luder G.(1988). Characterization of recombination-deficient mutants of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 170(7): 3001-3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carrasco B., Serrano E., Martin-Gonzalez A., Moreno-Herrero F. and Alonso J. C.(2019). Bacillus subtilis MutS modulates RecA-mediated DNA strand exchange between divergent DNA sequences. Front Microbiol 10: 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carrasco B., Serrano E., Sanchez H., Wyman C. and Alonso J. C.(2016). Chromosomal transformation in Bacillus subtilis is a non-polar recombination reaction. Nucleic Acids Res 44(6): 2754-2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen I., Christie P. J. and Dubnau D.(2005). The ins and outs of DNA transfer in bacteria. Science 310(5753): 1456-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen I. and Dubnau D.(2004). DNA uptake during bacterial transformation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2(3): 241-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dubnau D., Davidoff-Abelson R., Scher B. and Cirigliano C.(1973) Fate of transforming deoxyribonucleic acid after uptake by competent Bacillus subtilis: phenotypic characterization of radiation-sensitive recombination-deficient mutants. J Bacteriol 114(1): 273-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnston C., Campo N., Berge M. J., Polard P. and Claverys J. P.(2014). Streptococcus pneumoniae, le transformiste. Trends Microbiol 22(3): 113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kidane D., Ayora S., Sweasy J. B., Graumann P. L. and Alonso J. C.(2012). The cell pole: the site of cross talk between the DNA uptake and genetic recombination machinery. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 47(6): 531-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nicholson W. L., and Maughan H.(2002). The spectrum of spontaneous rifampin resistance mutations in the rpoB gene of Bacillus subtilis 168 spores differs from that of vegetative cells and resembles that of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of bacteriology. 184(17): 4936-4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takeuchi N., Kaneko K. and Koonin E. V.(2014). Horizontal gene transfer can rescue prokaryotes from Muller's ratchet: benefit of DNA from dead cells and population subdivision. G3(Bethesda) 4(2): 325-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomas C. M. and Nielsen K. M.(2005). Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 3(9): 711-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yadav T., Carrasco B., Hejna J., Suzuki Y., Takeyasu K. and Alonso J. C.(2013). Bacillus subtilis DprA recruits RecA onto single-stranded DNA and mediates annealing of complementary strands coated by SsbB and SsbA. J Biol Chem 288(31): 22437-22450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yadav T., Carrasco B., Myers A. R., George N. P., Keck J. L. and Alonso J. C.(2012). Genetic recombination in Bacillus subtilis: a division of labor between two single-strand DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 40(12): 5546-5559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]