Abstract

This paper analyses the choice of subsidy offered to a vaccine supply chain with a risk-averse buyer. We find that for a higher innovation effort and level of social benefits, the per-unit production subsidy is better when there is a low innovation cost coefficient, a low level of risk aversion, or a high potential demand. Otherwise, under the opposite conditions, the R&D innovation effort subsidy should be selected. Furthermore, from an evolutionary game theoretical perspective, we also present the stability performance for the subsidies, and the results show that when the manufacturer’s innovation cost coefficient is relatively low, the more profitable per-unit production subsidy may be abandoned due to its performance instability.

Keywords: Supply chain management, Government subsidy, Accumulated social benefit, Vaccines, Evolutionarily stable strategy

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 has increased the demand for medical products, such as face masks, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and vaccines, which need to be provided in a short timeframe. To motivate self-interested manufacturers to raise production quantities and improve research and development (R&D) innovation, the government may provide several types of subsidies to guide relevant companies to make appropriate decisions and maximize social welfare. The two most common subsidy policies are the per-unit production subsidy and the R&D innovation effort subsidy. Under a per-unit production subsidy policy, the government will provide a per-unit production subsidy for each of the products sold to the market, and the manufacturer’s unit product cost will then decrease. For example, facing the COVID-19 outbreak, the Hong Kong government announced it would provide a HK$30 billion government package to help the city’s healthcare sector combat the deadly coronavirus1 . As part of this package, the mask subsidy scheme offers manufacturers the capacity to expand.

In addition to the per-unit production subsidy, the government may also offer a R&D innovation effort subsidy for emergency-good manufacturers in order to compensate them for the lack of functionality in existing products, improve the quality of the existing products or develop new products. For example, to encourage development of the COVID-19 vaccine R&D, the Philippines government subsidizes vaccine developers and has pledged to provide 10 million Philippine pesos in incentives to companies or individuals who successfully develop vaccines2 . This paper explores the government’s choice between per-unit production subsidies and innovation effort subsidies offered to vaccine manufacturers and analyses the optimal subsidy policy from the perspectives of production quantity, innovation level and social benefits.

In addition, because no one can predict when the virus will spread or when vaccines will be available, there usually exists a mismatch between demand and supply in the vaccine market (Deo and Corbett, 2009). The mismatch arises primarily from the uncertainty in demand. We consider that the vaccine manufacturers distribute the products through a hospital or clinic (buyer); then, the risk will be borne by the buyer, who determines the order quantities before the demand is realized. The buyers, especially the small clinics, hate the risk of market demand fluctuations. The level of risk aversion of the buyer will affect its order strategy and then affect the manufacturer’s strategy and the subsidy policy. Therefore, it is meaningful to consider the uncertainty in demand and to study the impact of risk-averse behaviour on subsidy policies.

Furthermore, in most cases, facing emergencies and unknown viruses, due to the lack of reference and information, the government has to adjust the subsidy policy over time until a stable equilibrium is reached, which means that the government is bounded by rationality (Bischi et al., 1999). Therefore, this paper also contributes to the existing studies by considering the stability performance of the subsidy policy from an evolutionary game theoretical perspective. Specifically, as the government usually provides the subsidy policy before the manufacturers’ make their decision, it does not know how the manufacturer will react after accepting the subsidy. Facing complex conditions and considering consumer surplus, company profits and other specific objectives, it is not easy for the government to determine which subsidy policy is better. Therefore, the government has to adjust the subsidies carefully before reaching equilibrium. In reality, some governments often adjust subsidies by considering changes in the external environment (Anand et al., 2013). For example, Saudi Arabia’s government adjusts subsidies for water, electricity, and petroleum products based on its 2016 budget document3 . Facing COVID-19 challenges, Canada’s government plans to adjust the Canada emergency wage subsidy. If approved by Parliament, the new subsidy policy may help employers protect their jobs4 . Another reason why we consider the government is bounded by rationality is that subsidization may induce adverse effects or opportunistic behaviours, such as cheating and overinvestment (Zhang et al., 2019, Han et al., 2019). For example, a company named “Qingyu goose industry” in Shenyang has been involved in cheating, receiving subsidies for cold chain logistics subsidies of up to 7.87 million yuan5 .

In conclusion, this paper aims to consider a vaccine supply chain consisting of a manufacturer and a buyer and in which the demand is uncertain and the buyer is risk averse. The government may choose a per-unit production subsidy or an innovation effort subsidy to support vaccine R&D and production. The government is motivated by the need to address the following issues:

-

1.

Which type of subsidy will perform better in improving sales, innovation efforts or social benefits?

-

2.

How does the uncertainty in demand and the firm’s sensitivity to the uncertainty affect the choice of subsidy?

-

3.

How does the government choose a subsidy policy that comprehensively considers profitability and performance stability?

To solve these problems, this paper considers three scenarios: a no subsidy case (indexed by superscript NS) as a benchmark model; a per-unit production subsidy case (indexed by superscript PS); and an innovation effort subsidy case (indexed by superscript ES). We first discuss the feasible conditions for these two types of subsidies, which are treated as the primary conditions for the studies in the following sections. Then, by comparing the equilibrium outcomes obtained under the two types of subsidies, we study which subsidy benefits the sales, innovation effort and social benefits more. Finally, we model the dynamic adjustment process of the subsidy from an evolutionary game theoretical perspective and to highlight the importance of system stability, introduce the harmful effects of unstable systems. Considering both stability and profitability performances, we propose a way to choose a suitable subsidy. We find the following.

-

1.

The per-unit production subsidy is better than the innovation effort subsidy in raising the production quantity. Facing an emergency, the government should offer a per-unit production subsidy for the manufacturers in order to increase the production quantity in a short time. Another interesting finding is that in improving the innovation effort, adopting an innovation effort subsidy does not always produce a better performance than does adopting a per-unit production subsidy. When the potential demand is relatively high, the per-unit production subsidy can improve the innovation effort better than the innovation effort subsidy. Only if the innovation cost is sufficiently high should the government subsidize the innovation directly and cover some of the innovation costs, as the direct subsidy to innovation can induce the manufacturer to put forth a higher innovation effort. The subsidy choice for generating a higher innovation effort is consistent with that for providing a higher social benefit.

-

2.

Considering the uncertainty in demand and the risk preference of the decision-maker, we find that the production quantity and innovation effort will decrease in the demand uncertainty and the risk sensitivity of the decision-maker. The government will also provide fewer subsidies under a higher level of demand uncertainty and decision-maker risk sensitivity. Demand uncertainty and risk sensitivity also affect the choice of subsidy for higher innovation effort and social benefits. In particular, with a relatively high level of demand uncertainty and buyer risk sensitivity, the innovation effort subsidy can better promote innovation and social benefits. Otherwise, the per-unit production subsidy is better. In contrast, with a relatively high level of yield uncertainty and manufacturer risk sensitivity, the effect of per-unit production subsidies will increase, and the effect of innovation effort subsidies will decrease.

-

3.

Evaluating the way the stability condition is reached for both types of subsidies, we present evolutionarily stable equilibrium outcomes. We reveal the fact that equilibrium cannot be reached in an unstable system. If the more profitable subsidy is not stable but the less profitable subsidy is stable, the government should select the less profitable subsidy because it can result in higher accumulated social benefits. In general, the innovation effort subsidy should be selected when the innovation effort leads to a high cost of innovation but a low cost of per-unit production. Under the opposite conditions, the per-unit production subsidy should be chosen.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the studies closely related to our investigation. Section 3 describes the models and the corresponding equilibrium outcomes. The analysis of the equilibrium outcomes is presented in Section 4. The analysis is expanded in Section 5. Managerial insights and implications are discussed in Section 6. Section 7 concludes this paper and suggests future research directions. For clarity, the proofs are deferred to the Appendix.

2. Literature review

This paper is related to three streams of literature. The first stream focuses on the vaccine supply chain. The second stream concentrates on subsidy policy, and the last stream is related to the evolutionary game of government policy and supply chain systems.

2.1. Vaccine supply chain

There are many existing studies considering the mismatch between demand and supply in the vaccine market. Deo and Corbett (2009) studies the competition between manufacturers and the effect of yield uncertainty on the firms’ entry and production decisions. Dai et al. (2016) study a supply chain contracting problem in the presence of uncertainties surrounding the design, delivery, and demand of the influenza vaccine. Chick et al. (2017) consider the optimal procurement contract between the government and a for-profit supplier in a vaccine supply chain, in which the supply is uncertain and the production effort is unverifiable. To guarantee the timely and adequate supply of vaccines, Shamsi G. et al. (2018) adopt an SIR model to establish a contract for sourcing from one main supplier and one backup supplier. Wu et al. (2019) also indicate that the vaccine supply usually uses a multisourcing strategy to address supply uncertainty. Arifoglu and Tang (2020) consider an influenza vaccine supply chain in which both the yield and individual infection cost are uncertain. They design a two-sided incentive program, and the results show that when the realized supply is high, vaccinations become more affordable and demand will increase. Considering the impacts of COVID-19 on the service operations, Choi (2020) compares the “static service operations” and the “bring-service-near-your-home” mobile service operations, and studies the influence of different subsidy policies on the service operations. Westerink-Duijzer et al. (2020) indicate that vaccination usually suffers from delayed deliveries and limited stockpiles, while health agencies can improve the utilization efficiency by cooperating and sharing their doses.

The supply chain risks that decision makers need to face are widespread (Hamdan and Diabat, 2020, Choi et al., 2019, Xie et al., 2020, Zhao et al., 2020). As the epidemic outbreak may cause the supply chain risk, some studies focus on the impacts of the epidemic outbreaks on the supply chain based on the case of COVID-19 (Ivanov, 2020, Govindan et al., 2020, Nikolopoulos et al., 2021). Recently, Duijzer et al. (2018) review the existing studies on the vaccine supply chain and indicate the importance and existence of supply and demand uncertainty on the vaccine production. In particular, they highlight the demand uncertainty that can come from two aspects, one is due to the government procurement policy, the other one is due to the individuals perceived risk and safety of becoming infected. We will focus on the demand uncertainty in the main model and consider both supply and demand uncertainty in the extension. The uncertainties in delivery and demand make the buyer reduce the order size, and then the manufacturer will lose incentive improve its delivery performance, forming a negative feedback loop. Moreover, confronting with the demand uncertainty, the supply chain members may be risk aversion when making decisions (Yu and Zhang, 2018, Zhong et al., 2020, Li et al., 2018). As for the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreaks, Egbendewemondzozo et al. (2013) show that the effectiveness of vaccination depends on flock density in the region and risk aversion preferences of the decision maker. Massin et al. (2015) analyze the impact of risk preference of the general practitioners (GPs) on their decisions, finding that a riskaverse GP will be more likely to be vaccinated and be willing to recommend influenza vaccination more to his patients. Rahimian et al. (2019) indicate that the risk and demand ambiguity in newsvendor models (i.e., vaccine production) can be alleviated by using distributionally robust optimization.

Further, from the perspective of the government, some studies find that the equilibrium demand is always fewer than the socially optimal demand because self-interested individuals do not internalize the social benefit of protecting others via reduced infectiousness. Arifoglu et al. (2012) show that the equilibrium demand can be greater than the socially optimal demand considering the limited supply. Another reason that causes it difficult to reach a socially optimal level of vaccine coverage is the network effects. Focusing on infectious diseases, the existence of a negative network externality makes it difficult for vaccine coverage to reach a socially optimal level. Motivated by this, Adida et al. (2013) consider a monopoly market for an imperfect vaccine and provide a two-part menu of subsidies that successfully leads to a socially efficient level of coverage. Ghosh and Shah (2015) study the way how the government provides subsidy to induce a socially optimal vaccine coverage. Apart from the subsidy, the contract can also promote the social benefits and achieve vaccine supply chain coordination. Chick et al. (2008) design a cost-sharing contract offering to the buyer (governmental public health service) and supplier (vaccine manufacturer) so that the supply chain achieves global optimization and hence improves the supply of vaccines. Dai et al. (2016) provide a contract to incentivize at-risk early production and eliminate double marginalization. Lin et al. (2020) also study a two-echelon vaccine supply chain consisting a distributor and a retailer (hospital or clinic) and study the choice between a cold chain or non-cold chain to transport the vaccines.

Different from the above literature, we extend the vaccine supply chain by considering the government subsidy strategy when examining the manufacturer’s R&D effort and the buyer’s risk averse attitude. In addition, we use an evolutionary game to evaluate the stability performance under two subsidy schemes.

2.2. Subsidy policy

Many governments have established policies on sustainable development, resource use, and energy efficiency. Companies need to move towards sustainability if they wish to survive and remain competitive. Sinayi and Rastibarzoki (2018) study the impact of different government policies (imposing a tax or paying a subsidy on the products) on the supply chain’s sustainability level. They consider the demand to be a function of the price and the green degree of the product. Basiri and Heydari (2017) examine the competition between green products and non-green traditional products. Hafezalkotob (2017) studies the problem of how to subsidize a domestic manufacturer to compete with a foreign supplier for a sustainable development objective. Comparing the cases with and without a government subsidy, Liu et al. (2019) study how to encourage enterprises to undertake corporate social responsibility (CSR) and maintain the sustainable development of society. To improve the use of resources, some subsidies are offered to the closed-loop supply chain. He et al. (2019) consider the impact of a government subsidy on a closed-loop supply chain and present the optimal subsidy level to minimize the environmental impact. Hong et al. (2016) study government subsidies offered to a reverse supply chain. In addition, the government may provide subsidies to support the development of electric vehicles (Gu et al., 2017), desalinated water (Jia et al., 2019) and agricultural products (Peng and Pang, 2019).

Government incentives may take various forms (Chen et al., 2019). For example, the government may directly subsidize the production process for outputs or capacity investment. Sometimes the government supports domestic firms by taxing foreign-made products heavily (Hafezalkotob, 2017). Some studies compare the performance of different subsidy policies. Guo et al. (2016) compare two types of subsidies: one is a subsidy rate for the cost, and the other is a per-unit production subsidy. Considering a situation in which the government provides a single-period procurement decision and a two-period procurement decision, Nielsen et al. (2019) compare the performances of these two incentive policies on the greening level, consumer surplus and environmental improvement. Chen et al. (2019) examine how to choose a better subsidy from a per-unit production subsidy and innovation effort subsidy in order to motivate sustainability innovation.

This paper is most related to Chen et al. (2019), which also compares the performances of a per-unit production subsidy and an innovation effort subsidy. This work differs from that study in the following ways: (1) We study a subsidy offered to the vaccine supply chain, which exhibits a changeable and uncertain demand. (2) We consider the risk preference of the firm and study its impact on the subsidy choice. (3) We model the subsidy adjustment from an evolutionary game theoretical perspective and highlight the importance of system stability in obtaining an equilibrium and accumulated social benefits.

2.3. Evolutionary game in supply chain

Today, more and more research focus on the evolutionary game in the supply chain as it can better describe the decision adjustment process under imperfect information. Especially for the government, it usually makes decisions without sufficient reference (Yang et al., 2018, Sun and Zhang, 2019). Zhang and Li (2018) construct an evolutionary game model of haze cooperative control between the heterogeneity governments and provide evolutionarily stable strategies with compensation and punishment mechanisms. According to a real-world case study, Mahmoudi and Rastibarzoki (2018) model the decision adjustment process for a sustainable supply chain under government subsidy. Considering the government subsidy offered to the green supply chain, Sun et al. (2019) model the evolutionary game between manufacturers and material suppliers and find the evolutionarily stable strategies for suppliers and manufacturers. Jiang et al. (2019) study the government’s choice to balance the pursuit of environmental quality with the economic payoffs. They explore the evolution of different participants’ behavior and their evolutionarily stable strategy. Wang et al. (2019) study the manufacturing service allocation in a cloud manufacturing system. They find the equilibrium obtained in an evolutionary game model, and analyze the stability of evolutionary equilibrium for the manufacturing services game. Johari et al. (2019) examine the pricing decision adjustment of the manufacturers and study the impact of corporate social responsibility on the decisions. Evolutionary game benefits for the long-run performance analysis, Babu and Mohan (2018) identify the sustainability of a supply chain with the equilibrium of the system over a long (but finite) period after integrating the various dimensions such as environment, society, economy, culture, and governance.

3. The model

This paper considers a vaccine supply chain consisting of a manufacturer (the only manufacturer with independent R&D capabilities for a specific vaccine) and a buyer (a hospital or a clinic) (Chick et al., 2008). The manufacturer exerts an R&D innovation effort to improve the effectiveness of the vaccine; this improvement will attract more customers for the vaccine, even though the vaccine’s selling price may increase (Deo and Corbett, 2009, Chen et al., 2019). Especially in emergencies, most people believe that new technology will bring better effects, and they are willing to pay more for new technology products. For example, when buying masks, people are willing to pay more for N95 masks with breathing valves than for ordinary masks. Therefore, the market demand can be denoted as , where represents the stochastic potential demand, i.e., the reservation price, with a mean and variance . is the quantity elasticity. The manufacturer produces vaccines and provides them to the buyer at a wholesale price of . Further, the inverse demand function can be denoted as , where is the order quantity that is endogenously determined by the buyer and is the contribution coefficient of the innovation effort to the price. For simplicity, we normalize , and the profit function of the buyer can be denoted as .

In addition, as no one can predict when the epidemic will be terminated, the demand for vaccines is filled with uncertainty. In our model, the buyer bears all the uncertain risk because all the vaccine products will be delivered once the order is placed. Thus, the buyer would to some extent have a risk-averse attitude. We follow Tsay, 2002, Gan et al., 2009, Hafezalkotob, 2017 and use the mean–variance method to measure the buyer’s risk-averse behaviour:

| (1) |

where captures the degree of the buyer’s risk averse attitude; i.e., the buyer is more risk averse with a higher .

Consistent with Chen et al., 2019, Ge et al., 2014, to capture the decreasing marginal effect of an effort, we consider the innovation effort cost to be the quadratic form . is the coefficient of the effort cost and measures the rate at which the cost increases with increasing effort. The innovation effort also affects the manufacturer’s unit production cost. Therefore, the per-unit production cost is modelled as , where is the cost when the effort decreases to zero. To simplify the model, we normalize to be zero. measures the rate at which the per-unit production cost increases with increasing effort. We assume to ensure the existence of the per-unit production subsidy. Given the order quantity and the subsidy , the profit function of the manufacturer is given as:

| (2) |

In Eq. (2), denotes the total expenditure on government subsidies. Thus, and represent the expenditure on non-subsidies, per-unit production subsidies and innovation effort subsidies offered to the manufacturer, respectively. The forms of the two subsidies are consistent with those in Chen et al. (2019). Here, we need to explain the effect of different forms of subsidies (i.e., a linear function for the per-unit production subsidy and a quadratic function for the innovation effort subsidy) on the comparability between the two subsidies. First, the different forms of subsidies are consistent with the forms of the costs. It is reasonable that the cost of innovation (innovation investment) is easier to measure than the effect of innovation when the subsidy is provided. Second, and most importantly, the forms of the two types of subsidies are not the main factors that the government needs to consider when making decisions. The government is more interested in which type of subsidy will bring more social benefits or increase the production quantity.

In both cases, to make it easier to express the model with uniform notation, we further define as the government decision, where is the subsidy offered for per-unit production and is the subsidy provided for the effect of the innovation effort.

Following Krass et al., 2013, Raz and Ovchinnikov, 2015, Chen et al., 2019, the government decides on the amount of subsidy to maximize the same objective function (3).

| (3) |

For ease of expression, we name the “social benefit”. The first term of the function (3) denotes the external benefits of the R&D innovation effort ( is a constant marginal benefit in the effort level). For example, during the innovation process of one product, researchers often find other research results. The R&D of one product is conducive to promoting the development of related industries. The second term is the total expenditure on the two types of subsidies provided to the manufacturer. The remaining terms are social welfare, which includes the profits of the manufacturer and the buyer, and the consumers’ surplus , which is given as follows:

| (4) |

The sequence of events is as follows:

-

1.

The government announces the subsidy policy and the amount of subsidy ;

-

2.

The manufacturer determines the innovation effort and the wholesale price ; and

-

3.

The buyer decides the order quantity .

Take the per-unit production subsidy case as an example. With backward induction, the best response function (BRF) of the order quantity can be solved out by the first-order condition after checking . Then, the BRF of the order quantity, which is represented by , is .

Knowing the buyer’s reaction, the manufacturer determines the BRF of and . The Hessian Matrix is:

| (5) |

Then, the first-order principal minor , and the second-order principal minor . The function is jointly concave in if the Hessian Matrix is negative definite. The condition for the Hessian Matrix is negative definite is and . Reducing , we have that ensures the existence of the optimal solutions. The BRFs of and are optimal and unique and are given as:

| (6) |

Substituting and into the utility function of the government, we can check the existence of the optimal

subsidy . Note that . We can see that ensures the existence and uniqueness of the solution . Since , we can obtain the threshold . According to the first-order condition, the optimal can be solved out and given as:

| (7) |

Substituting into , and , we can obtain the optimal solutions , and . Similarly, the optimal solutions under no subsidy and innovation effort subsidy cases can also be solved out. All the results are given in Lemma 1.

Lemma 1

The equilibrium outcomes are given inTable 1.

Corollary 1

Under two types of subsidies, the production quantity, innovation effortand the amount of subsidydecrease inand.

Table 1.

The equilibrium outcomes obtained in three scenarios.

| No subsidy case | Per-unit production subsidy case | Innovation effort subsidy case |

|---|---|---|

Corollary 1 indicates that if the level of demand uncertainty is higher or the buyer is more sensitive to the risk of uncertainty, the buyer will order less from the vaccine manufacturer, and the manufacturer will also input less in innovation. Meanwhile, the government will also provide fewer subsidies. We can see that the uncertain demand and the buyer’s risk sensitivity have a significant negative effect on vaccine production and R&D, which is not good for an anti-epidemic therapy.

4. Results analysis

4.1. Analysis on the equilibrium outcomes

4.1.1. The basic conditions

For ease of writing, we define , and have the following.

Proposition 1

Giventhe subsidy works well when equilibrium exists.

-

(1)

Without any subsidy, equilibrium exists when .

-

(2)

Equilibrium exists under a per-unit production subsidy when .

-

(3)

Equilibrium exists under innovation effort subsidies when .

Proposition 1 indicates that basic conditions exist for the adoption of government subsidies. In general, only when the cost coefficient for R&D innovation is relatively high can the subsidies work well. Otherwise, equilibrium does not exist. For both types of subsidies, if is lower than the thresholds or , we have the second-order principal minor of the Hessian matrix of lower than zero, meaning that the profit function is not jointly concave in and and that there is no equilibrium under either of the subsidies. Proposition 1 also shows that if the cost coefficient is too large, i.e., if , only an innovation effort subsidy is feasible. The upper bound guarantees when . In this case, the basic condition we mention above ensures the existence of the range ; i.e., .

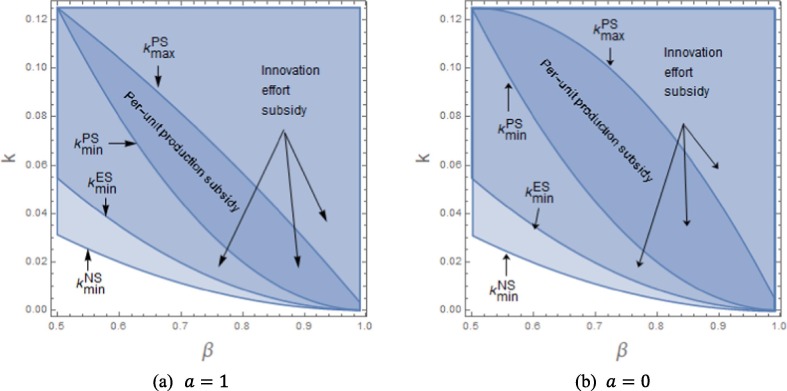

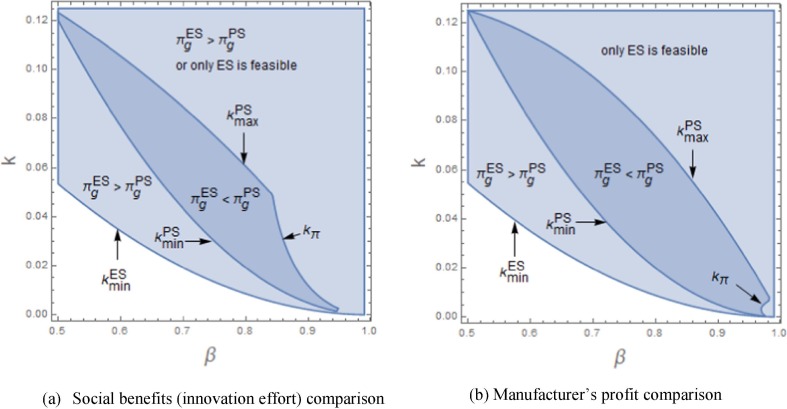

Note that ; we can see that the innovation effort subsidy has a larger scope of application than the per-unit production subsidy. The innovation effort subsidy may be provided to manufacturers with and , while the per-unit production subsidy will not. Setting and , we draw the feasible regions under both types of subsidies with respect to and , as shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

The feasible domains under different scenarios with respect to and .

Fig. 1 shows the feasible domains of the two types of subsidies with respect to and . As the size relationship of the four thresholds is determined, i.e., , the parameter setting only affects the size of the feasible regions and does not affect the conclusion that the feasible domain of the innovation effort subsidy is greater than that of the per-unit production subsidy. Comparing Fig. 1(a) with (b), we can see that if the external benefits of the innovation () are relatively large, the feasible domain of the per-unit production subsidy will be relatively small. This is because the external benefits affect the wholesale price through the subsidy . The increase in external benefits raises the wholesale price and then prevents buyers with less severe capacity constraints from joining capacity sharing.

4.1.2. The impact of subsidy policy

In this subsection, we will explore the impact of the government subsidy policy on production, R&D innovation and the benefits to all stakeholders. We study this problem by comparing the equilibrium outcomes obtained with and without the subsidies. Then, we have the following.

Proposition 2

Comparing the equilibrium outcomes obtained with and without the subsidies, we can conclude the following.

-

(1)

Both the manufacturer and the buyer can benefit from both types of subsidies. The government can also obtain a higher social benefit by providing subsidies. Formally, we have the following:

-

(2)

The demand and innovation effort can be improved under both types of subsidies. Formally, we have the following:

If the necessary conditions in Proposition 1 hold to ensure the application of the subsidies, all the decision-makers can benefit from both types of subsidies. Regardless of whether the subsidy is provided for the innovation effort or for per-unit production, it can improve both the production quantity and the R&D innovation. This indicates that the equilibrium order quantity without any subsidy is always less than the socially optimal demand. This conclusion is consistent with that raised by the existing literature, as we have mentioned above. The conclusion that the subsidy can improve the buyer and supplier’s profit seems to be intuitive. However, the innovation effort improved by the subsidy may also lead to high fixed and variable costs. The increasing cost may be larger than the profit gain obtained by a high effort e because of the decreasing marginal effect of the effort. Moreover, the government can also benefit from providing subsidies to the manufacturer. This motivates the government to provide the subsidy. Proposition 2 indicates that all decision-makers are willing to provide or accept subsidies.

If we define the gap between and as the advantage of subsidy on the production quantity, we can conclude the following.

Corollary 2

The advantage of the production quantity increases inandand decreases inand. The advantages of both R&D innovation and social benefits increase inandand decrease inand.

This means that if the potential demand is relatively large, both types of subsidies can better promote the production quantities. However, if the uncertainty in potential demand is relatively large or the buyer is relatively sensitive to the risk, the promotion in production quantities may not be so significant. Similarly, the promotion in production and profits will be more significant when the potential demand is larger, the uncertainty in demand is smaller or the buyer is less sensitive to the risk.

As both types of subsidies improve the production quantity, R&D innovation and the profit (social benefits) of all stakeholders, the government should provide subsidies when the necessary conditions shown in Proposition 1 hold. Then, we wonder which subsidy results in better performance in production quantity, R&D innovation and the profits (social benefits) of the stakeholders and how the government chooses a better subsidy when both types of subsidies are feasible .

4.1.3. Comparison on the production quantities

In the face of emergencies, the government hopes to increase the production quantities of vaccines and face masks in a short time. It is very important to find the subsidy that improves the production quantities more. Then, we have the following.

Proposition 3

Given, the production quantityfor vaccines under a per-unit production subsidy is larger than that under an innovation effort subsidy; i.e.,.

Proposition 3 considers the case in which both types of subsidies are feasible. This indicates that the per-unit production subsidy can raise the production quantity more than can the R&D innovation subsidy if the two types of subsidies are feasible. COVID-19 has caused a shortage of some emerging goods, such as face masks, safety goggles, and effective vaccines. Proposition 3 indicates that the government can increase production quantities more by providing a per-unit production subsidy to manufacturers than by providing an R&D innovation effort subsidy when the cost for innovation is relatively large (). As , we can see that the advantage of the per-unit production subsidy in promoting quantity will increase when the potential demand increases. For various vaccines, the quantities of those vaccines with high potential demand can be motivated more by providing per-unit production subsidies than by providing the R&D innovation effort subsidies.

If the cost of innovation effort is relatively low, i.e., if , the only feasible innovation effort subsidy should be selected for its ability to offer a production quantity improvement that is better than that offered by the per-unit production subsidy, which is not feasible to make the system reach equilibrium.

This finding indicates that for a larger production quantity, the subsidy should be selected according to the characteristics of the innovation cost. If the innovation cost is relatively high, the innovation effort subsidy will perform poorly in motivating manufacturers to produce, and the subsidy should therefore be offered directly on production. In contrast, if the innovation cost is relatively low, the innovation effort subsidy can further motivate manufacturers to produce by taking advantage of the low innovation cost.

4.1.4. Comparison on the innovation efforts

In addition to facilitating an increase in sales, the government expects vaccine manufacturers to invest more in R&D in order to ensure the provision of effective vaccine products, especially when the current vaccines are unable to provide protection against the changed virus. Comparing the equilibrium innovation effort with , we have the following.

Proposition 4

The innovation effort e under the per-unit production subsidy will be higher than that under the innovation effort subsidy (i.e.,) if either of the following conditions holds.

(a). (b). (c). .

Proposition 4 considers the case when both types of subsidies are feasible; i.e., . Proposition 4(a) shows that if the cost of innovation is relatively low (lower than the threshold ), the per-unit production subsidy can better promote the R&D innovation effort. If the innovation cost is high, the government should subsidize the innovation directly and help the manufacturer cover some of the innovation costs, thereby motivating the manufacturer to exert a higher innovation effort. This conclusion is consistent with Chen et al. (2019). However, if we further consider the case with , innovation effort is the only choice, although the innovation cost is much lower than .

For vaccines with different potential demands, the government should provide a per-unit production subsidy for those with high potential demand because the subsidy can better increase the order quantity of the buyer to meet the great demand. For vaccines with low potential demand, the subsidy should be offered to the innovation process, and then the innovation effort can be promoted better.

Furthermore, if the buyer is not as sensitive to uncertainty, the government should subsidize the manufacturer’s per-unit production and motivate the buyer to order more. If the buyer is sensitive to uncertainty, the buyer will prefer to order less due to its best response function . Then, the government should not focus on sales improvement. Instead, it should subsidize the innovation directly.

4.1.5. Comparison on the profits (social benefits)

As the government makes decisions about which type of subsidy to offer, while considering the feasible conditions, we compare the social benefits. The decision cannot be made by just comparing and because one subsidy may be the only one selected. Since the feasible conditions of the innovation effort subsidy are more significant than those of the per-unit production subsidy, we can see that only when the per-unit production subsidy results in a larger than the innovation effort subsidy (i.e., satisfying the following condition (8)) will the government offer a per-unit production subsidy.

Otherwise (i.e., satisfying the following condition (9)), the government will (or can only) offer an innovation effort subsidy.

Proposition 5

Comparing the profits (social benefits) obtained under two types of subsidies, we have the following:

-

(1)

Both the buyer and manufacturer can benefit more from per-unit production subsidies than from R&D innovation effort subsidies. Formally,;

-

(2)

For higher social benefit, the government will offer per-unit production subsidies if either of the following conditions holds; otherwise, the government will offer innovation effort subsidies.

(a). (b). (c) .

Proposition 5(1) shows that the manufacturer is more willing to accept the per-unit production subsidy for more profit gaining; the buyer can also benefit more if the government provides a per-unit production subsidy to the manufacturer.

Proposition 5(2) indicates that if the per-unit production subsidy is feasible, the government will provide it rather than the innovation effort subsidy when the R&D innovation cost is relatively low. Otherwise, for vaccines with high R&D innovation costs, the government has to offer subsidies directly to support innovation efforts.

For a given , the government should provide the R&D innovation effort subsidy if the buyer is relatively sensitive to uncertainty (a larger ). In this situation, the buyer, who may be cautious, may place a low order according to its best response function . When the buyer is not sensitive to uncertainty, the government should provide a per-unit production subsidy, which can directly induce the buyer to order more according to Proposition 3.

From the perspective of the potential demand , the government should provide per-unit production subsidies for “expensive” vaccines with higher potential demand and provide R&D innovation effort subsidies for those with lower potential demand. Facing a greater potential demand, the subsidy on per-unit production can better raise the production quantities to meet the greater demand. On the other hand, vaccines with relatively low potential demand may be developed during the development process. They should be subsidized in the R&D innovation process.

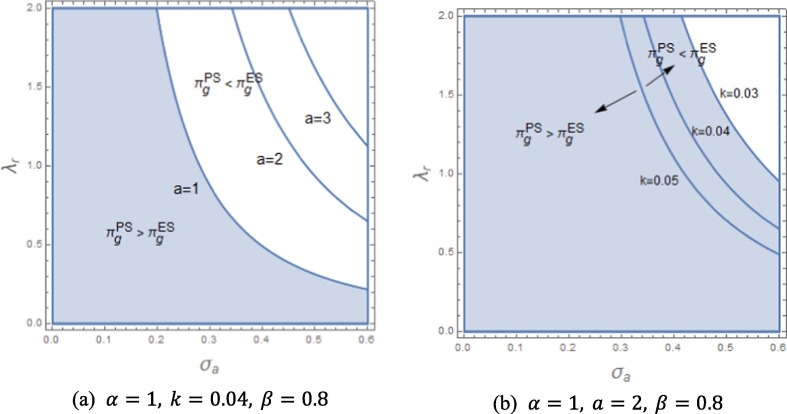

To better show the government’s choice for a higher social benefit, we show the impacts of cost coefficients ( and ) and uncertain factors ( and ) on the government’s choice of subsidy, as shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 , respectively.

Fig. 2.

Profitability comparison with respect to the cost coefficients and .

Fig. 3.

The social benefit comparison with respect to the uncertainty factors and .

Fig. 2 shows the social benefit comparison with respect to the cost coefficients and . The dark colour region with represents , in which the government will provide a per-unit production subsidy to the manufacturer. Otherwise, the R&D innovation effort subsidy will be provided.

Fig. 3 shows that the government can obtain more social benefits by providing a per-unit production subsidy than an R&D innovation effort subsidy when the uncertainty level in demand is relatively low (a lower ), and the buyer is not sensitive to uncertainty (a lower ). The potential demand and cost coefficient also affect the threshold between the two regions. More specifically, an increasing or a decreasing will enlarge the region of , which proves the conclusions of Proposition 5 (2).

4.2. Stability analysis

The high degree of uncertainty makes it difficult for governments to suggest an optimal way to subsidize manufacturers in a short period of time. Because of its long distance from the market, the government can sometimes only infer information about the market by constantly observing the decision-making behaviour of manufacturers and gradually adjusting the amount of subsidy until a short-term equilibrium is reached (Bischi et al., 1999). Therefore, governments often adjust subsidies to better fulfil their role in promoting the development of an industry. For example, China’s subsidy policy for new energy vehicles was adjusted on the eve of New Year’s Day 2017. The adjustment raised the technical thresholds for subsidies and lowered the subsidy standards appropriately6 . In most cases, the virus spreads rapidly and creates high uncertainty. Hence, we consider the government to keep adjusting its decisions following a nonlinear discrete-time decision-making rule, which is given as follows:

| (10) |

In Eq. (10), the index represents the subsidy decision under the per-unit production subsidy and innovation effort subsidy cases, respectively. represents the subsidy decision in the next period ; this decision is made based on the adjustment of the decision in the current period . The direction of adjustment is determined by the marginal social benefit . Specifically, the government will increase (decrease) the decisions at period t if the marginal social benefit at period t is positive (negative). The parameter gI controls the speed of adjustment. It is not difficult to see that the adjustment stops when . Then, we have and obtain the fixed points including the boundary equilibrium and Nash equilibrium points . Obviously, the adjustment speed does not affect the equilibrium. It only influences the time and the number of iterations reaching equilibrium. As the government will provide a positive subsidy, we only study the Nash equilibrium points obtained when . Based on Ma and Xie (2018), we can obtain the conditions for the asymptotic stability of a first-order system:

Lemma 2

The equilibriumis locally stable when, where.

In Section 4.1, we have discussed the choice of subsidies considering their profitability performances. However, equilibrium can only be reached in a stable decision-making system. The lemma presents the stability criterion, which will be applied to judge the stability condition for the system under different types of subsidies. Based on Lemma 2, we can solve the condition to ensure system stability.

Proposition 6

Under two types of subsidies, we can find an upper bound ofensuring the existence of evolutionarily stable strategies in system I. More specifically, we observe the following:

-

(1)

The system PS reaches an evolutionarily stable strategy under a per-unit production subsidy when;

-

(2)

The system ES reaches an evolutionarily stable strategy under the innovation effort subsidy when.

Proposition 6 indicates that for both systems, lowering the speed of decision adjustment is better for system stability. Moreover, a larger threshold means a better stability performance for the system . The reason is that although the parameter does not affect the equilibrium outcomes, it will affect the number of iterations to reach equilibrium. A low ensures stability but delays the time that the decision-maker obtains the optimal solutions. As a result, if the decision can be adjusted with a larger under control of the system, it can obtain the optimal decision as quickly as possible and obtain a higher accumulated social benefit. Based on this, we can study how other parameters affect the stability of the system by checking the sensitivity analysis of these parameters on . For example, note that , we can see that a larger leads to a larger and a better stability performance of system PS.

As it can prove that the necessary conditions shown in Proposition 1 are sufficient to guarantee and , we can see that the system can always be stable if the decision-maker is willing to choose a sufficiently low speed of adjustment . As we have explained the negative effect of a low on the social benefit gaining, we consider a given and check other parameters’ influences on the system stability. Ensuring the stability of the system , the thresholds (such as ) of other parameters can be solved out by the equation , where J has been defined in Lemma 2.

To better show the stable condition with respect to different parameters, we introduce the stable region diagrams. To show the harmful effects of the unstable system, we present the time series of the decisions and accumulated social benefits under the stable and unstable system and compare them.

4.2.1. Stable region

Fig. 4(a) shows the stable regions covering the feasible regions of the per-unit production subsidy. In general, the parameter combination results in a stable system when is sufficiently high (i.e., when ), as represented by the dark region shown in Fig. 4(a). We can also see the regions with , where the per-unit production subsidy is suitable but will lead to an unstable system. Similar conclusions can be made according to Fig. 4(b).

Fig. 4.

Stable regions with respect to the cost coefficients and .

Setting , we study how the uncertainty factors affect the system stability, as shown in Fig. 5 .

Fig. 5.

Stable regions with respect to the uncertainty factors and .

From the perspective of the risk preference and uncertainty level, Fig. 5 shows the impact of uncertainty factors on the stability of systems PS and ES. The uncertainty factors’ impacts on the stability of system PS are not as obvious as those of system ES. Fig. 5(a) implies that within the feasible region, the uncertainty factor combination makes the system stable. Fig. 5(b) shows that the system ES can be stable when the buyer is not as sensitive to the risk and when the uncertainty level is low.

4.2.2. Time series of the decisions

By introducing the negative effect of the chaos system, we further highlight the importance of keeping the system stable. Under a per-unit production subsidy with , Fig. 6 shows the time series of the subsidy in different states of the system PS. Take Fig. 6(a) for example. According to the stable region diagram, we set to simulate the stable system, the doubling-period bifurcation system, and the chaotic system, respectively. Since does not affect the optimal equilibrium outcomes, three lines should converge to one line. However, we can see that after the preliminary adjustment, the decision presents different states. In a stable system with , the subsidy reaches equilibrium after several adjustments. If , the system goes into the doubling-period state, where the decision will shock around the equilibrium point but never reach it. In a chaotic system with , we cannot see any pattern or rule about how the subsidy changes. Similar conclusions can be made according to Fig. 6(c) and (d), which illustrate the time series of the subsidy offered for the R&D innovation effort.

Fig. 6.

Time series of the subsidy under different system states.

4.2.3. Accumulated social benefits

In an unstable system, the subsidy decision cannot reach the optimal value after a period of adjustment. Instead, it will oscillate around the optimal value or even appear to be in chaos. As a result, social benefit cannot be maximized. The accumulated social benefit diagrams clearly show that the accumulated social benefit can be much higher in a stable system than in an unstable system. As discussed before, does not affect the equilibrium outcomes. However, in Fig. 7 (a), a different leads to different accumulated social benefits due to the different states of the systems. In Fig. 7(b), although a higher leads to a lower equilibrium , the accumulated social benefit under a higher is much higher than that with a lower . This is because a higher results in a stable system, in which the relatively lower equilibrium can be achieved. The lower leads to the instability of the system and then hurts the accumulated social benefits. Similar conclusions can be made according to Fig. 7(c) and (d).

Fig. 7.

Accumulated social benefits under different system states.

4.2.4. A time-varying adjustment parameter

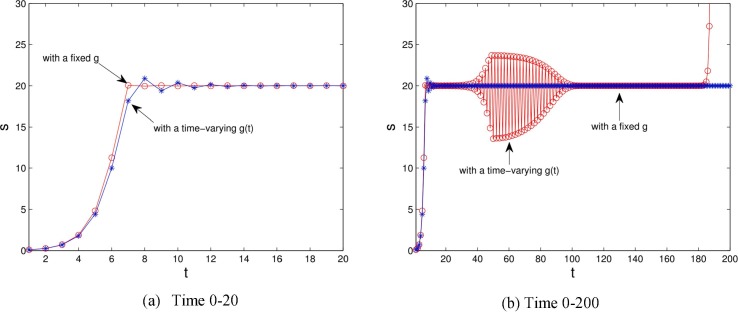

As far as we know, almost all the existing papers assume the adjustment speed to be fixed. When the government comes to understand the market in the process of subsidy policy adjustment, it will get more information to draw on in decision adjustments. In this subsection, we consider a time-varying adjustment parameter to model the learning effect of the government in adjusting subsidies. To model the diminishing marginal effects, we need to satisfy and. Therefore, we set , where . Setting , we compare the time series for subsidies under a fixed (by setting ) and a time-varying in Fig. 8 .

Fig. 8.

The comparison on time series of the subsidies with a fixed and a time-varying .

Obviously, the time-varying adjustment parameter does not change the optimal solution . However, it will shorten the time to reach equilibrium. This depicts how government can adjust subsidies to optimal levels more quickly as it gains market information. On the other side, a relatively large will cause chaos and affect the stability performance for the subsidies according to Proposition 6. As shown in Fig. 8 (a), a time-varying shortens the time to reach equilibrium. When the speed of adjustment continues to increase, the system will enter the state of period-doubling bifurcation ( in Fig. 8 (b)) and eventually go into chaos state ( in Fig. 8 (b)).

4.3. The subsidy choice considering profitability and stability performance

Setting , and , Fig. 9 (a) integrates the stable regions of two systems, which are shown in Fig. 4(a) and (b). The subregions in Fig. 9 are numerous and complex. For clarity and simplicity of presentation, each subregion is assigned a number . The line in Fig. 9 (b) divides the subregions and into two parts. We name these subregions and , where and . In Fig. 9(a), region () and region () are the stable regions under per-unit production subsidies and innovation effort subsidies. In the coincident region (), both subsidy policies can keep the system stable.

Fig. 9.

The choice of subsidy considering profitability and stability.

As only in a stable system can the decision-maker reach the optimal decision, the government should consider stability performance to be much more important than profitability performance. Fig. 9(b) integrates the profitability comparison and stability comparison. According to the stability performance of the two systems, we can divide the regions shown in Fig. 9(b) into 4 groups.

Group 1 includes Regions () and (). These are regions in which no subsidy can ensure the system will be stable, although the system satisfies the necessary condition for the adoption of subsidies. The government should slow down the adjustment speed of and to make the system stable.

Group 2 includes Regions () and (). These are regions in which only the innovation effort subsidy can keep the system stable. The government can only choose innovation effort subsidies, although in region (), the equilibrium social benefits cannot be obtained in a chaotic system.

Group 3 includes Region (). These are regions in which only the per-unit production subsidy can keep the system stable. The government can only choose a per-unit production subsidy, although in region (), the equilibrium social benefits because the social benefit cannot be obtained in a chaotic system.

Group 4 includes Region (). In this region, both subsidy policies make the system stable. Then, the government can choose a subsidy according to its profitability performance. In region (), we have , and the per-unit production subsidy will be offered. In region (), we have , and the innovation effort subsidy will be selected.

We provide the subsidy selections in Table 2 considering all the scenarios above.(See Table 3 )

Table 2.

The selection of subsidy policy considering the stability and profitability performances.

| Group | Region | Sub-region | System PS | System ES | Profitability | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unstable | Unstable | Slow down | |||

| Unstable | Unstable | Slow down | ||||

| Unstable | Unstable | Slow down | ||||

| Unstable | Unstable | Slow down | ||||

| 2 | Unstable | Stable | innovation effort subsidy | |||

| Unstable | Stable | innovation effort subsidy | ||||

| Unstable | Stable | innovation effort subsidy | ||||

| Unstable | Stable | N/A | innovation effort subsidy | |||

| 3 | Stable | Unstable | per-unit production subsidy | |||

| Stable | Unstable | per-unit production subsidy | ||||

| 4 | Stable | Stable | per-unit production subsidy | |||

| Stable | Stable | innovation effort subsidy |

Table 3.

The equilibrium outcomes under a relatively stringent quality standard.

| Per-unit production subsidy case | Innovation effort subsidy case |

|---|---|

In Group 1, both the systems are unstable. The government should slow down the adjustment speed to achieve a stable system. In Group 2, the innovation effort subsidy is the only choice because another subsidy policy leads to an unstable system, although the combination may be located in region R3, where and the per-unit production subsidy may reach a higher equilibrium social benefit. A similar conclusion can be made in Group 3, where the per-unit production subsidy is the only option. In Group 4, both systems can be stable, and the subsidy policy is determined by comparing the equilibrium social benefits. This rule is followed by most of the existing studies.

Take the subregion in Group 3 as an example. Following the set and of Fig. 9, we can select a combination in region R71. Without loss of generality, we select , and then we have and . According to the equilibrium social benefit , the innovation effort subsidy should be selected. However, the final decision should be the per-unit production subsidy because of the stability performance. In other words, the accumulated social benefit under the per-unit production subsidy is much higher than that under the innovation effort subsidy, as shown in Fig. 10 .

Fig. 10.

Accumulated social benefit comparison under the case for region R71.

5. Extensions

In this section, the analysis is expanded to consider the impacts of an uncertain yield and a strict quality standard on the main findings of this paper. We also consider the case in which both types of subsidies are offered simultaneously, and we compare the effect of such a combined subsidy to that of a separately provided subsidy. The extended research helps check the robustness of the findings.

5.1. The uncertain yield

In our main model, we focus on exploring the demand uncertainty in the vaccine supply chain. In this subsection, we make a robustness check to confirm that both the demand and supply are uncertain (Chick et al., 2008, Deo and Corbett, 2009, Cho, 2010). Consequently, when the buyer places an order of , it will be the production quantity targeted by the manufacturer. Due to the existence of unexpected factors such as the defective rate, the actual quantity produced is , where is a random variable reflecting the random yield for the manufacturer. We assume the random variable to have the mean and variance . Because of the importance of vaccine products, shortages are not allowed. Therefore, the manufacturer needs to find ways to make up for the defective product . The manufacturer can purchase from foreign manufacturers while also temporarily expanding its capacity to cover shortages. Further, the per-unit production cost (represented by ) is assumed to be larger than the cost of normal production. Then, the profit function of the buyer is given as follows:

| (11) |

The manufacturer is also assumed to be risk averse and maximizes the following utility model (12):

| (12) |

where represents the manufacturer’s sensitivity to the variance of the yield rate.

The government then provides subsidies for maximizing the following utility model (13):

| (13) |

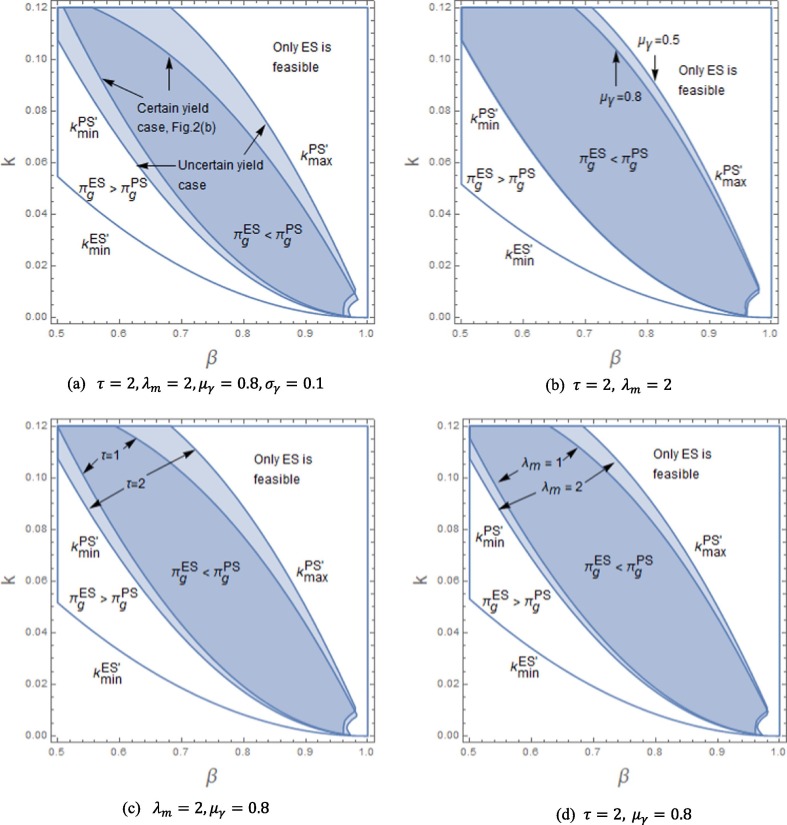

The equilibrium outcomes are given in the Appendix. Following the same value settings () and letting to simulate the uncertain yield and the risk-averse manufacturer, we can obtain the choice of subsidy and make a comparison with the preceding situation, as shown in Fig. 11 (a).

Fig. 11.

Profitability comparisons considering uncertain yield.

Comparing the “Certain yield case (Fig. 2(b))” with the “Uncertain yield case” in Fig. 11(a), we find that the region where enlarges. This means that when considering the uncertain yield and the risk-averse manufacturer, the odds of the per-unit production subsidy being selected increases. Given the default values we can further check the impacts of , and on the choice of subsidies, as shown in Fig. 11(b)-(c).

Fig. 11(b) shows that the region where the per-unit production subsidy is better will enlarge when the yield uncertainty becomes severe (a lower mean ). This reveals that if the manufacturer cannot control the yield well enough, the per-unit production subsidy can better encourage the manufacturer to produce more.

Fig. 11(c) shows that the region where the per-unit production subsidy is better will enlarge when the backup production cost increases. This indicates that when the losses caused by yield uncertainty are significant, the per-unit production subsidy will be more likely to cut the manufacturer’s losses.

Fig. 11(d) shows that the region where the per-unit production subsidy is better will enlarge when the manufacturer’s coefficient of risk aversion increases. The choice of the subsidy varies by target manufacturers with different levels of risk aversion.

According to the numerical simulation, the region in which is larger with a larger and a lower . The more severe the yield uncertainty or the more sensitive the manufacturer is to the uncertain risk, the more likely the per-unit production subsidy is to be selected.

5.2. The strict quality standard

In this subsection, we consider that the government has a clear requirement for quality standards (i.e., a lower bound for the quality ) for vaccine products. The quality is assumed to be linearly related to the innovation effort of the manufacturer; i.e., . Then, the constrained extreme-value problem of the manufacturer is:

| (14) |

The optimal solutions can be made by the Lagrange multiplier method. The Lagrange function is . Take the per-unit production subsidy case as an example. Table 1 shows the equilibrium solutions for and when the innovation effort makes the quality meet the requirement. If , the requirement for quality will not bind the manufacturer’s decision on , and the equilibrium outcomes are the same as those in Table 1. If the quality standard is relatively high, i.e., , the constraint binds, and the optimal innovation effort is . Similarly, for the innovation effort subsidy case, if , the quality constraint will not bind the manufacturer’s decision, and the equilibrium outcomes are the same as those in Table 1. On the contrary, if , the constraint binds, and the optimal innovation effort is . Interestingly, we find that the innovation effort subsidy will not motivate the manufacturer and has nothing to do with .

Considering the relatively stringent quality standard , the optimal solutions are as follows:

Lemma 3 indicates that if the government requires a relatively stringent quality standard for the vaccine, it does not need to subsidize the innovation effort. The requirement for quality drives the manufacturer to make efforts to improve quality voluntarily.

Proposition 7

The per-unit production subsidy can better improve quantities and social welfare and will benefit both the manufacturer and the buyer. More specifically,.

Proposition 7 indicates that if the government has a relatively high requirement for vaccine quality, the per-unit production subsidy has a better performance not only in production quantity but also in the level of benefits realized by the buyer, manufacturer and the government. This is because the high quality level required by the government has already driven the improvement of innovation; therefore, the innovation effort subsidy will not be as effective.

5.3. Both types of subsidies are provided

In this subsection, we consider that the government can provide per-unit production and innovation effort subsidies simultaneously to the manufacturer (Chen et al., 2019). Using superscript PES to index the parameters and variables in this combined subsidy case, the amount of subsidy is modelled as , where and represent the subsidy for per-unit production and the innovation effect, respectively.

Lemma 4

With both types of subsidies offered,ensures the existence and uniqueness of equilibrium solutions. The equilibrium outcomes are given as:

.

Note that the lower bound is , and the upper bound is represented with . We can prove the following:

| (15) |

In the preceding paragraphs, we have assumed . Therefore, we have , meaning that the combined subsidy has a broader feasible domain than the per-unit production subsidy. This is very important when determining which subsidy policy to select. In addition, we can also obtain some interesting findings comparing the performances of combined subsidies and separately provided subsidies.

Proposition 8

Comparing the performance of the combined subsidy and separately provided subsidies, we observe the following:

-

(1)

The amount of the unit subsidy under the combined subsidy is less than that when the two subsidies are applied separately; i.e., ;

-

(2)

In improving the innovation effort, the combined subsidy is better than the per-unit production subsidy, better than the innovation effort subsidy when, and worse than the innovation effort subsidy when;

-

(3)

In improving the production quantity, there is no difference between the combined subsidy and per-unit production subsidy; the combined subsidy is better than the innovation effort subsidy whenand worse than the innovation effort subsidy when;

-

(4)

In improving social benefits, the combined subsidy is better than the per-unit production subsidy, better than the innovation effort subsidy when, and worse than the innovation effort subsidy when;

-

(5)

In improving the manufacturer’s profit, the combined subsidy is worse than the per-unit production subsidy, better than the innovation effort subsidy when, and worse than innovation effort subsidy when;

-

(6)

In improving the buyer’s utility, there is no difference between the combined subsidy and the per-unit production subsidy; the combined subsidy is better than the innovation effort subsidy whenand worse than the innovation effort subsidy when.

Therefore, the combined subsidy is better than the innovation effort subsidy when is relatively large, i.e., when , but worse than the innovation effort subsidy when is relatively small; i.e., in improving the innovation effort, production quantity, social benefits, the manufacturer’s profit, and the buyer’s utility. The combined subsidy does not differ from the per-unit production subsidy in terms of production quantity and buyer’s utility improvement. The combined subsidy is better than the per-unit production subsidy in improving the innovation effort and social benefits but worse than the per-unit production subsidy in improving the manufacturer’s profit.

Fig. 12 shows the choice of subsidy policy including the combined subsidy. Fig. 12(a) shows that when , in improving social benefit, the combined subsidy performs better than the two separately offered subsidies. If , the separately offered innovation effort subsidy is the best choice. Fig. 12(a) can also be used to show the innovation effort comparison. Fig. 12(b) describes the performances of different subsidy policies on the manufacturer’s profit gains. When , the per-unit production subsidy benefits the manufacturer more than it does others. If , the innovation effort subsidy benefits the manufacturer more.

Fig. 12.

The performance comparisons among different subsidy policies.

6. Managerial insights and implications

In the face of outbreaks such as COVID-19, there is an urgent need for R&D departments to develop effective vaccine products as soon as possible. Due to the rapid spread of the epidemic, the market also has higher demands to produce vaccines. Only by getting more people vaccinated as soon as possible can the government more effectively stop the further spread of the epidemic. Governments often provide subsidies to promote the production and innovation of vaccine products to better control the spread of a disease. Motivated by this, to provide a reference for the government to select a better subsidy policy, this paper analyses the effects of different government subsidies (the per-unit production subsidy and the innovation effort subsidy) in terms of vaccine production quantity and innovation effort level and considers the effects of market demand and supply uncertainty, as well as the risk preference of vaccine manufacturers and buyers and the strict quality requirements of vaccine products.

Consider the case where both subsidy options are feasible. The first insight is that, faced with a reliable vaccine, the government should give a direct per-unit subsidy if it wants the production of the vaccine to ramp up quickly. If the government wants to better promote vaccine innovation, it should give innovation effort subsidies when the cost of innovation is high and should indirectly promote vaccine innovation through per-unit subsidies when the cost of vaccine innovation is relatively low. Similarly, if the government targets an aggregate social benefit as a decision goal, it also needs to provide innovation effort subsidies when innovation costs are high and per-unit subsidies when innovation costs are low.

Consider the uncertainty in demand and the risk preferences of the buyer. The second insight is that the government is more likely to use per-unit production subsidies when there is less uncertainty in market demand or when the buyer is less risk averse; conversely, when there is more uncertainty and the buyer is more risk averse, the government is more likely to use innovation effort subsidies. This is because the per-unit production subsidy directly reduces production costs and promotes higher output. The subsidy works better only if the buyer is insensitive to risk. Otherwise, a sensitive buyer tends to order fewer products, rendering the per-unit production subsidy useless in terms of yield improvement. Conversely, the per-unit production subsidy will be more likely to be optimal if there is greater supply uncertainty or if manufacturers are more risk averse. This is because this subsidy method directly subsidizes production costs and promotes higher output. This can be a good way to compensate or mitigate supply shortages caused by quality and other problems in the production process.

The third insight is that for government departments that have insufficient access to market information or in situations in which manufacturers and buyers have more market information, government departments can only adjust the reduction in a subsidy until equilibrium is reached. The problem is that interference supplementation may affect the adjustment process of government compensation. Especially when the subsidy amount is about to be equalized, outside interference may cause the adjustment of the subsidy to go back to the beginning. In this case, the government needs to incorporate the ability to withstand external disturbances into its decision-making process for the subsidy program and prioritize the stability and profitability of the subsidy to achieve a higher cumulative social benefit.

The fourth insight is that if the government imposes strict quality standards on vaccine products, then the innovation effort subsidy will be ineffective and the per-unit production subsidy will be strictly superior to the innovation effort subsidy in terms of yield, as well as the benefit to all parties. This is because government mandates make manufacturers voluntarily invest in innovation resources, and in this situation, it is more effective for governments to use per-unit subsidies.

7. Conclusions

The outbreak of COVID-19 has increased the demand for medical products such as face masks and vaccines. As self-interested firms will not make decisions considering social benefits, the government should provide subsidies to motivate production quantity and R&D innovation. Inspired by this, this paper studies a vaccine supply chain consisting of a manufacturer and a risk-averse buyer under government subsidies. It finds that both types of subsidies can promote production quantities, R&D innovations, and social benefits for all stakeholders. For vaccines with higher potential demand, both types of subsidies can better promote production quantities, R&D innovations, and social benefits. However, if the uncertainty in potential demand is relatively larger or the buyer is more intensive to the risk, the promotions in production quantities, R&D innovations and the social benefits will be less significant. Comparing the two types of subsidies, we find that per-unit production subsidies should be selected if the needs for vaccines greatly increase in a short time. If the government focuses on R&D innovation or the total social benefits, the per-unit production subsidy should be chosen when the cost of innovation is relatively low, the potential demand is relatively high, or the buyer is not as sensitive to the risk from uncertain demand. Otherwise, the subsidy should be provided to the R&D innovation.

Considering the imperfect information referred to by the government, we model the subsidy adjustment process for the government from an evolutionary game perspective. Providing a way to find an evolutionarily stable strategy, we highlight the importance of stability performance in decision-making by introducing the time series of the decisions and accumulated social benefits in different states of the system. We prove that the stable subsidy is better off than the profitable subsidy with respect to the accumulated long-run social benefits.

Regarding future research directions, we can further study the impact of yield uncertainty on the firms’ equilibrium strategies and the choice of government subsidy. Also, it will be interesting to study the oligopoly buyers and manufacturers competing in the market. The competition will change the way the firms make decisions and may lead to double marginalization. Then the supply chain coordination will be a future research direction.

Funding

The first author acknowledges support from the Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China [Grant No. 20YJC630166], the Social Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China (Grant No. 20DGLJO10) and the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University.

The second author acknowledges support from the Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China [Grants No. 20YJC630037] and support from the Science and Technology Program of Tianjin, China [Grants No. 19ZLZXZF00290].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lei Xie: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Pengwen Hou: Conceptualization, Supervision, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition. Hongshuai Han: Writing - review & editing, Formal analysis.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive, helpful and insightful comments which led to a major improvement of this paper. This work was supported by the Project of Humanities and Social Sciences for Young Scholars, the Chinese Ministry of Education, [No. 20YJC630166, No. 20YJC630037], Social Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China [No. 20DGLJO10] and the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, [No. 71802145].

Footnotes

Appendix A.

Proof of Corollary 1:

The conclusions can be made based on the followings. The impact of uncertain demand and risk aversion on:

The production quantities:

The R&D innovation efforts:

The amounts of subsidy

Proof of Proposition 1:

For ease of writing, we define the thresholds:

and , and we have due to: . The basic condition ensures , i.e., the existence of the per-unit subsidy.

Proof of Proposition 2:

The results in Proposition 2 can easily get by the “Reduce” function of the Wolfram Mathematica software.

Proof of Corollary 2:

The conclusions are made based on the followings. The impacts of parameters on the advantages in:

Productions quantities

R&D innovation efforts:

Social benefits:

Proof of Proposition 3:

We can prove with because only when will the condition holds. When k,we have and , and

Proof of Proposition 4:

The thresholds can be obtained by making We provide the thresholds as , where

can be solved out by making and the existence of it can be proved by the numerical simulation in this paper.

Proof of Proposition 5:

-

(1)

The conclusions obtain by the “Reduce” function of the Wolfram Mathematica software.

-

(2)

The thresholds can be obtained by making We provide the thresholds as:

, where

=, where

Implications of government subsidy on the vaccine product R&D when the buyer is risk averse

, where .

Proof of Proposition 6:

The threshold can obtain by making. Given the expression of below, we have:

, and

Then the system I is stable with

It is not difficult to prove that guarantees ,and

guarantees .

To check the impacts of the parameters on the system stability (i.e.,), we have

, and

There exists a threshold satisfying:

The threshold can be solved out as:

where

Implications of government subsidy on the vaccine product R&D when the buyer is risk aversewhere

, where

To check the impacts of parameters on the stability performance, we have:

Proof of Proposition 7:

The corresponding profits and utilities can be given as:

The equilibrium outcomes of the model in Section 5.1.

Proof of Lemma 4:

Substituting into the basic model, the BRF of in the third step is given as , with can be proved easily.

In the second step, the Hessian Matrix should be negative definite. Hence, the first- and second-order principal minors should satisfy , where .

We first assume the condition achieves and get the BRFs of and to be and .

In the first step, the Hessian Matrix should be negative definite and first- and second-order principal minors should satisfy , where

We also assume the condition achieves and get the optimal and to be:

Substitute and back to the above BRFs and principal minors. The optimal solutions can be solved out and shown in Lemma 4. Reducing , we can get , being the basic condition for the existence and uniqueness for the optimal solutions. To further ensure all the decision variables to be larger than 0, should further satisfy .

Proof of Proposition 8:

The amount of unit subsidy:

Improving the innovation effort:

Improving the production quantity:

Improving social benefits:

Improving the manufacturer’s profit

when ,

,

, where

Improving the buyer’s utility:

References

- Adida E., Dey D., Mamani H. Operational issues and network effects in vaccine markets. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013;231(2):414–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2013.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]