Abstract

Introduction

Maternal delivery at home without skilled care at birth is a major public health issue. The current study aimed to assess the various contributing and eliminating factors of maternal delivery at home in India. The reasons for not delivering at healthcare facilities were also explored.

Methods

The study used the National Family Health Surveys (NFHS)-4 (2015–2016) data from states and union territories of India for analysis. A national representative sample of 699,686 women of reproductive age group (15–49 years) was used. Cross-tabulation and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed.

Results

The prevalence of home delivery in India was 22%, among which 34% of women believed that institutional delivery was not a necessity. Financial constraints, lack of proper transportation facilities, non-accessibility of healthcare institutions and not getting permission from family members were the main reasons cited by the women for delivering at home. The proportion of home deliveries was much higher among women from more disadvantaged socioeconomic areas than women from less disadvantaged socioeconomic areas. Domestic violence and partner control were essential factors contributing to the prevalence of home delivery. However, the women who owned mobile phones and used a short message service (SMS) facility delivered at home less often.

Conclusion

Policymakers should focus more on the women living in disadvantaged socioeconomic areas and other marginalised populations with less education and low economic levels to provide them with optimum delivery care utilisation. Strengthening of public healthcare facilities and more effective use of skilled birth attendents and their networking are essential steps. Electronic and economic empowerment of women should be emphasised to bring about a significant reduction in the proportion of home deliveries in India.

Keywords: Empowerment, Home delivery, India, Maternal health, Maternal mortality, Socioeconomic neighbourhood disadvantage index, Women’s health

Key Summary Points

| In India, 22% of women deliver at home. |

| In India, 34% of women think that institutional delivery is not necessary. |

| In India, 14% of women face problems because of the high economic costs of institutional delivery. |

| In India, 12% of women are not allowed by their husbands or household members to deliver at a healthcare facility. |

| Women living in socioeconomic disdvantaged areas deliver more often at home. |

| Women who use mobile phones deliver more often at a healthcare facility. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13128536.

Introduction

Maternal death is a severe public health problem where home delivery without skilled care at birth has a significant detrimental impact [1, 2]. Almost 295,000 mothers died from various pregnancy and childbirth-related problems in 2017, accounting for approximately 810 maternal deaths every day [2]. Facility-based delivery care before, during and after childbirth can save thousands of mothers’ lives [3]. Childbirth at home is a major contributing factor to such staggering numbers of maternal deaths in the absence of skilled birth attendants. Most importantly, as women are dying from preventable causes during childbirth, non-institutional or home delivery needs to be eliminated [4]. Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG-3) targets: “reducing the global MMR to less than 70 per 100,000 births, with no country having a maternal mortality rate of more than twice the global average”. During 2000–2017, MMR has decreased 38% worldwide [2]. UN agencies and documents have reiterated the significance of facilty-based delivery and eliminating home delivery in reducing maternal and neonatal deaths in low- and middle-income countries [4].

Almost 94% of maternal deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including India [1]. India reported almost 45,000 maternal deaths in 2015. Different demographic, socioeconomic and policy level factors influence institutional or home delivery without skilled care [2, 3]. Available studies in India have presented local or regional scenarios and mainly focused on access to maternal healthcare facilities [7–12]. A comprehensive national study exploring the background, individual and family level factors, including empowerment and controlling factors, could enrich the existing knowledge and help to better understand the home delivery situation. An in-depth analysis of maternal home delivery and the role of the related factors could extend our knowledge further. Of interest, the current study aimed to assess various contributing and eliminating factors related to maternal delivery at home in India. Also, the causes for not delivering at healthcare facilities were explored.

Methods

The Government of India, in collaboration with Measures DHS, conducted the National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) to produce consistent excellence data on health and sociodemographic issues of both women and men. India has NFHS-1 (1992–1993), NFHS-2 (1998–1999), NFHS-3 (2005–2006) and NFHS-4 (2015–2016) to support policymakers in the health sector.

Sampling and Data Collection

NFHS-4 had two stages of sampling techniques for the rural areas and three stages for the urban areas, using the 2011 population census. Using probability proportional to size (PPS), primary sampling units (PSUs) were used to select villages in rural areas. Households were then randomly selected from the PSUs [13]. Using PPS, municipality wards were selected as PSUs in the urban areas. Then, census enumeration blocks (CEB) were randomly selected from each PSU and households were randomly selected from the CEB.

From January 2015 to 4 December 2016, field interviews were conducted by 789 trained field teams, who collected the data from 28,522 clusters in India. Each field team had three female and one male interviewer, two health investigators and the driver under the field supervisor. Initially, the survey selected 628,900 household samples. Among the selected households, 616,346 had prospective respondents. Finally, the study included 601,509 households. All women of reproductive age (15–49 years) who lived the night before the interview day in those selected households were considered as the eligible sample. A total of 699,686 women (15–49 years) were interviewed (97% response rate) using the NFHS questionnaires. A more detailed description of the survey, including sampling, questionnaires, data collection and data handling, is available elsewhere [13].

Dependent Variable

Any maternal delivery at a woman's own home, parents' home or other home constituted the primary variable, called 'home delivery'.

Independent Variables

Individual and family level factors included: age (seven groups: 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44 and 45–49 years); residency (rural and urban); education (no education, primary, secondary and higher education); religion (Hindu, Muslim and others); economic status (poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest); and sex of household head (female and male). The other variables were the husband's education (no education, primary, secondary and higher education), type of cooking fuel (solid or non-solid fuel), health insurance coverage (yes or no) and neighbourhood socioeconomic status (more disadvantaged and less disadvantaged).

Economic status was measured by the validated and widely used wealth index, a composite measure of the cumulative living standard of the household, introduced in India by Rutstein and Johnson [14, 15]. It primarily assesses the respondent’s ability to pay for healthcare facilities and the distribution of the health services among the poor. The wealth index includes ownership of household assets. Principal component analysis puts individual households on a continuous scale (standard normal distribution, mean = 0, SD = 1) of relative wealth. From the standardised scores, five different categories of wealth quintiles are estimated (poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest).

Solid fuel includes wood, charcoal, straw, shrubs, grass, coal, ignited agricultural crops, and cow or buffalo dung. Non-solid fuel is electricity or natural/liquid petroleum gas, biogas or kerosene. Generally, using solid fuel indicates a low socioeconomic status [16].

Neighbourhood socioeconomic (NSE) status is widely used for reviewing the influence of neighbourhood socioeconomic status on health [15, 17, 18]. The NSE index was constructed to assess whether the respondent lived in a less or more disadvantaged socioeconomic neighbourhood. The NSE index included four variables: the proportion of rural respondents, proportion of respondents living below the poverty level, respondents living in slum areas and proportion of illiterate respondents. Using principal component analysis (PCA), the continuous scores were estimated to classify neighbourhoods into two categories: (1) more disadvantaged and (2) less disadvantaged socioeconomic neighbourhood status.

Economic and electronic empowerment factors included working status (working and non-working), employment status (employed year round, seasonal employment, occasional employment), having money that the respondent alone can decide how to spend (yes, no), having a bank account (yes, no), knowledge of a programme in the neighbourhood area that gives loans to women to start or expand a business (yes, no), owning a mobile phone (yes, no) and being able to use SMS (yes, no). Seasonal employment indicated a kind of temporary employment for specific seasons, mostly with some certainty, for example, during monsoon season employment in the paddy field. Occasional labour means great uncertainty about getting any employment when seasonal employment was not available.

Domestic control and violence factors included the experience of emotional violence (yes, no), experience of physical violence (yes, no) and experience of any sexual violence (yes, no). Controlling issues included whether the woman was usually allowed to go to the market and to visit a healthcare facility. Each question had three options: 'not at all', 'can go alone' and 'can go with someone else'.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests were used to examine differences in proportions of exposure to IPV by demographic, socioeconomic and empowerment variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed with all demographic, socioeconomic and empowerment (including electronic) variables to assess their independent contribution in predicting exposure to IPV. IBM SPSS v25 was used for analysis. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

NFHS-4 used all necessary sampling techniques, emphasising consistency and comparability and ensuring the best quality of survey results [13]. The prevalence estimate of home delivery was estimated. For investigating the cross-relationship between home delivery and independent variables, we estimated proportions and conducted tests including adjusted standardised residuals. Multivariate logistic regressions were estimated to determine the possible association between home delivery and independent variables.

Data analysis was done using IBM SPSS v 25.

Ethical Permission

The current study was conducted using secondary data from NFHS-4. NFHS-4 received ethical approval from the Institutional Ethical Review Board (ref. no./IRB/NFHS-4/01_1/2015) of the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, India. No informed consent was required as this study used anonymised secondary data. However, the field staff and NFHS-4 had received informed consent from all participants.

Results

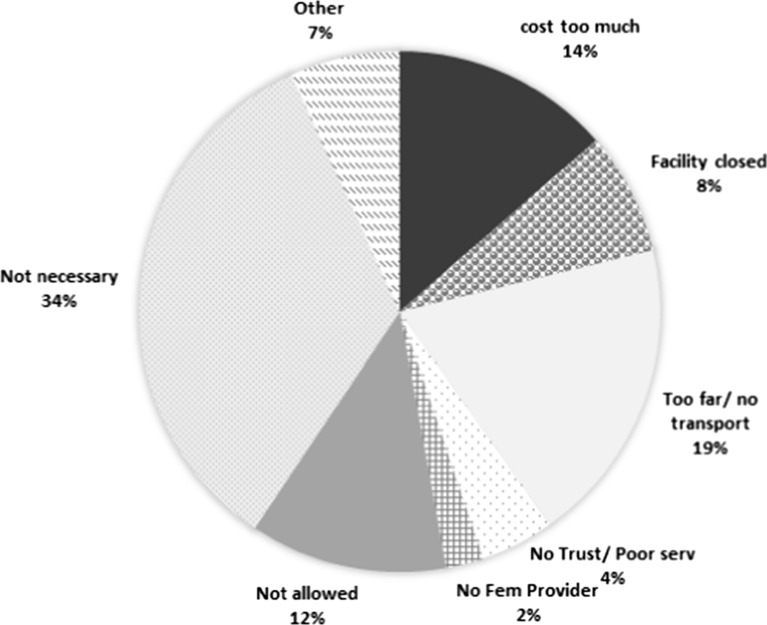

In India, more than one in every five mothers (22%) delivered at home. One in every three mothers (34%) who delivered at home believed that it was not necessary to deliver at a healthcare facility. One in every five mothers (19%) who delivered at home stated that the healthcare facility was too far away or they had no transportation to get to the facility. Among the mothers who delivered at home, 14% stated that this was because of the expense of going to a healthcare facility and 8% said that this was because the facilities were closed. Almost one in every eight mothers (12%) who delivered at home stated that they were not allowed to go to a healthcare facility to deliver their children (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Reasons for not delivering at a health facility

Older women delivered proportionately more at home (15–24 years = 18% vs. 45–49 years = 53%) than younger women. Rural women delivered proportionately more than twice as often at home than the urban women. A considerably high proportion (38%) of uneducated women delivered at home, while only 4% of the more highly educated women delivered at home. Women from other religions (non-Hindu and non-Muslim) delivered at home more often. Half of the poorest women had delivered at home. Women without health insurance coverage delivered more often (23%) at home than women with health insurance coverage (19%). Women from the families who used solid fuel delivered more (28%) at home compared to their peers who used non-solid fuel. Women from the more socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods delivered at home almost three and a half times more than their peers who were from less disadvantaged NSE areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Individual and family factors including neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage index for home delivery

| Respondents (N) | Home delivery (% of N) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | P < 0.001 | |

| 15–19 | 5898 | 18.9% |

| 20–24 | 56,181 | 18.4% |

| 25–29 | 70,162 | 23.8% |

| 30–34 | 37,309 | 23.8% |

| 35–39 | 15,344 | 30.2% |

| 40–44 | 4546 | 41.2% |

| 45–49 | 1357 | 53.3% |

| Residential area | P < 0.001 | |

| Urban | 47,814 | 11.5% |

| Rural | 142,983 | 25.6% |

| Education | P < 0.001 | |

| No education | 55,105 | 38.4% |

| Primary | 26,696 | 28.5% |

| Secondary | 88,847 | 14.1% |

| Higher | 20,149 | 4.1% |

| Religion | P < 0.001 | |

| Hindu | 138,263 | 18.9% |

| Muslim | 29,300 | 28.3% |

| Others | 23,234 | 33.4% |

| Sex of household head | ||

| Female | 167,828 | 22.0% |

| Male | 22,969 | 22.6% |

| Economic status | P < 0.001 | |

| Poorest | 46,753 | 40.7% |

| Poorer | 43,710 | 27.2% |

| Middle | 38,369 | 16.9% |

| Richer | 33,198 | 10.2% |

| Richest | 28,767 | 4.8% |

| Covered by health insurance | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 163,284 | 22.6% |

| Yes | 27,513 | 18.9% |

| Husband's education | P < 0.001 | |

| No education | 5603 | 40.3% |

| Primary | 4622 | 29.5% |

| Secondary | 18,302 | 16.8% |

| Higher | 4753 | 6.4% |

| Type of cooking fuel | P < 0.001 | |

| Non-solid | 58,763 | 8.7% |

| Solid | 132,034 | 28.0% |

| Neighbourhood socioeconomic status | P < 0.001 | |

| More disadvantaged | 106,881 | 31.9% |

| Less disadvantaged | 83,916 | 9.6% |

Seasonal or occasionally employed women delivered more at home than their peers who worked all year round. Women with bank accounts and with knowledge about bank loans or business delivered at home less often. Women who owned mobile phones or were able to use SMS devices delivered notably less at home (Table 2).

Table 2.

Economic and electronic empowerment factors behind home delivery

| No. of respondents (N) | Home delivery (% of N) | |

|---|---|---|

| Working status | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 27,519 | 19.8% |

| Yes | 5891 | 26.9% |

| Employment status | P < 0.001 | |

| All year round | 4219 | 23.8% |

| Seasonal | 3383 | 30.7% |

| Occasional | 474 | 31.9% |

| Respondent has money for own decision | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 20,418 | 22.9% |

| Yes | 12,992 | 18.1% |

| Bank account | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 17,046 | 27.3% |

| Yes | 16,364 | 14.5% |

| Knowledge of bank loans, start-ups, business | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 21,565 | 24.4% |

| Yes | 11,845 | 14.9% |

| Own mobile phone | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 16,555 | 27.7% |

| Yes | 16,855 | 14.5% |

| Can read SMS | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 4690 | 24.9% |

| Yes | 11,566 | 9.8% |

Women who experienced domestic violence (emotional, physical or sexual violence) delivered more at home than the women who did not face domestic violence. The proportion of home deliveries was higher among women who were not allowed to go shopping (22.5%) than among women who were allowed to go alone (20.3%) or accompanied by someone else (21.6%). Also, women who were not allowed to visit a health facility (23.9%) delivered at home more often than women who were allowed to go alone (19.7%) or accompanied by someone else (21.9%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Domestic control and violence factors behind home delivery

| No. of respondents (N) | Home delivery (% of N) | |

|---|---|---|

| Experienced emotional violence | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 22,128 | 20.9% |

| Yes | 3075 | 27.5% |

| Experienced any physical violence | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 18,051 | 19.4% |

| Yes | 7152 | 27.6% |

| Experienced any sexual violence | P < 0.001 | |

| No | 23,466 | 21.0% |

| Yes | 1737 | 30.8% |

| Allowed to go out for marketing | P < 0.001 | |

| Not at all | 3486 | 22.5% |

| Can go alone | 16,576 | 20.3% |

| Can go with someone else | 13,348 | 21.6% |

| Allowed to visit health facility | P < 0.001 | |

| Not at all | 2358 | 23.9% |

| Can go alone | 15,185 | 19.7% |

| Can go with someone else | 15,867 | 21.9% |

Younger women were less likely to deliver at home than older women. Uneducated women were almost four times more likely to deliver at home than more educated women. The women of non-Hindu and non-Muslim families were twice as likely to deliver at home. Women not having health insurance coverage were more likely to have home deliveries. Women living in more disadvantaged socioeconomic areas were twice as likely to deliver at home as women living in less disadvantaged socioeconomic areas. Women having money, a bank account, business knowledge or a mobile phone were less likely to deliver at home (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression

| OR | Lower interval | Upper interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 15–19 | |||

| 20–24 | 0.354 | 0.15 | 0.835 |

| 25–29 | 0.454 | 0.197 | 1.043 |

| 30–34 | 0.377 | 0.162 | 0.873 |

| 35–39 | |||

| 40–44 | |||

| 45–49 | Ref | ||

| Education | |||

| No education | 3.863 | 2.182 | 6.839 |

| Primary | 2.701 | 1.521 | 4.798 |

| Secondary | 2.087 | 1.33 | 3.276 |

| Higher | Ref | ||

| Religion | |||

| Hindu | Ref | ||

| Muslim | 1.416 | 1.013 | 1.979 |

| Others | 2.422 | 1.86 | 3.154 |

| Sex of household head | |||

| Female | 0.736 | 0.57 | 0.951 |

| Male | Ref | ||

| Type of cooking fuel | |||

| Non-solid | 0.539 | 0.394 | 0.737 |

| Solid | Ref | ||

| Covered by health insurance | |||

| No | 1.4 | 1.049 | 1.868 |

| Yes | Ref | ||

| Neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage | |||

| More disadvantage | 2.212 | 1.652 | 2.96 |

| Less disadvantage | Ref | ||

| Has money for own use | |||

| No | 1.301 | 1.04 | 1.629 |

| Yes | Ref | ||

| Own mobile phone | |||

| No | 2.25 | 2.131 | 2.377 |

| Yes | Ref | ||

A 95% confidence interval. Only significant results are presented in the table

Discussion

International and national agencies have undertaken several interventional strategies for reducing home delivery and enhancing facility-based deliveries using at least skilled care at birth. For example, the Government of India, in 2006, launched the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) framework. The main objective of this scheme was to promote institutional deliveries and to significantly decrease the number of home deliveries among poor women by upgrading the delivery and post-delivery services and providing incentives for food and transport to the pregnant mothers [19, 20]. The National Population Policy [21] indicated the need for promotion of facility-based delivery among Indian women to achieve improvement in the maternal mortality status of the country. Integration of the public healthcare system with the private sector and non-governmental organisations was the central strategy behind this policy [21, 22]. Despite the consistent efforts by the central and state governments in India, the current study revealed that 22% of Indian women still deliver at home. The reality, however, could be much worse. The primary reasons cited by the respondents for home delivery were non-accessibility of the healthcare facility, lack of transport, financial constraints, closed healthcare facilities and not getting permission from the family. Among the women who delivered at home, more than one-third believed that institutional delivery was not a necessity. A recent study from Africa reached the same findings [23]. Socio-cultural issues, religious beliefs, ignorance and incorrect perceptions of the women might be factors behind the notion that institutional delivery is not necessary. Also, low quality of care at the public healthcare facilities, long waiting times, unsuitability of times the facility is open and absence of healthcare providers aggravated their mistrust in the healthcare system, which prevented a group of women in India from seeking institutional delivery [24]. Previous research found that long waiting times indicate a health system's inefficiency and create a feeling of discontent among patients [25]. However, further in-depth qualitative studies are warranted to explore these issues. Another serious issue related to home delivery was getting permission from the family to deliver at a healthcare facility. Further contextual exploration is needed to determine why families are not allowing this. However, the findings of the present study showed that women believed institutional delivery was not necessary and families did not allow them to deliver at the facilities. Some deep-rooted misconceptions as well as social and religious taboos could have an immense influence on the burden of home delivery in India.

The current study indicated various predisposing factors standing in the way of facility-based delivery in India. The demographic factors were older age of women, rural location and Muslim religion, while the socioeconomic factors were lower education level, lower income and lack of health insurance coverage. Through the updated network of healthcare facilities and various government schemes introduced in the recent years, younger women have received better delivery care than older women. Moreover, the younger women, due to advancements in education and empowerment opportunities, were more aware of the adverse effects of home delivery and therefore delivered at the healthcare facilities [26–28]. On the other hand, older women who had given birth to their children almost 20–30 years earlier had no option but to deliver at home because of the lack of technological advancement and patient-centred healthcare. Moreover, they were more likely to have home deliveries during the births of their subsequent children because of their belief that they were at lower risk [22]. It is to be noted that the older women experienced higher proportions of domestic violence, both physical and emotional, as suggested by previous literature [29]. In low- and middle-income countries, neglect of healthcare was higher among women because of imbalance of power and existing health inequalities [30, 31]. The prevalence of domestic violence and abuse, along with its normalisation [32], could have a severe impact on their health-seeking behaviour, especially delivery care, leading to the staggering number of home deliveries among them. Therefore, policymakers must address these issues immediately to comply with national and international policies.

It is an issue of concern that about 1.28% of India's GDP is spent on public health expenditures, which is much lower than the global average and inadequate to serve its vast population [33]. The findings of the present study show a stark difference in the prevalence of home delivery among the households using solid fuels and those using non-solid fuels. Households using solid fuels for cooking are mostly found in poor and marginalised populations residing in the rural areas and urban slums. Women from these households delivered at home more often than women of higher socioeconomic status, indicated by the households using non-solid fuels for cooking. Financial constraints, lack of health insurance coverage and non-accessibility of healthcare facilities were significant barriers to delivery care among the economically weaker sections of society in India. Previous literature indicated that a wide disparity exists in healthcare uptake in general between rural and urban populations in India [24]. Due to the inaccessible geographical location of some villages, inadequate doctor-patient ratios and non-availability of skilled healthcare providers, women living in rural areas were often unable to obtain quality healthcare services for childbirth. A previous study conducted in India stated that the out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure incurred for delivery care was one of the primary reasons for the poor and marginalised population to opt for home deliveries, often unattended by skilled birth attendants (SBAs) or trained Dais [20, 34, 35]. A well-functioning public healthcare system, with the provision of adequate skilled healthcare providers and quality healthcare services, is necessary to address this inequity.

Lower education level of women is an essential factor contributing to the burden of home deliveries in India. Previous research conducted in African countries advocated the importance of female education for reducing the prevalence of home delivery by changing their preconceived notions and increasing their health awareness [23]. The present study stated that women owning bank accounts or having knowledge about bank loans and business delivered at home less often, probably because of their better decision-making power in the family. More educated and economically empowered women believed that institutional delivery was necessary, which increased their likelihood of facility-based deliveries [22]. Also, the present study revealed that women who owned mobile phones and used SMS devices had a lower prevalence of home deliveries. Electronic empowerment, in terms of usage of mobile phones and SMS facility, increased the awareness of women regarding various healthcare issues and thereby contributed to their further sensitisation [36–38]. By using mobile phones, the women living in rural India were able to stay in contact with healthcare workers such as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and received important updates, thereby helping them to seek proper delivery care. Further in-depth qualitative studies are warranted in this regard to fully understand the role of electronic empowerment in reducing the prevalence of home deliveries in India.

The effect of neighbourhood socioeconomic (NSE) status on health is an exciting factor that was analysed in the current study. The NSE index, indicating the effect of socioeconomic status on health, is a useful tool to differentiate between more and less disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Women in more disadvantaged socioeconomic areas, such as rural respondents, those living below the poverty level, respondents living in slum areas and illiterate respondents [17, 18], reported considerably higher proportions of home deliveries. Therefore, this could have a firm policy implication in the Indian context, with renewed focus and targeted interventions aimed at these vulnerable groups. The study could argue for setting up more healthcare facilities, including delivery services, at least in the vicinity of the more disadvantaged socioeconomic neighbourhoods. Increased strengthening of the public healthcare system in India, along with reinforcement of public-private partnership and alleviation of out-of-pocket expenditure, is the greatest current need to improve the facilty-based delivery status. Low- and middle-income countries in Africa, Bangladesh and Vietnam have fostered effective partnerships with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) for the provision of high-quality maternal and child health services [39–43]. In the Indian context, the role of NGOs in ensuring quality delivery care, especially to women in disadvantaged socioeconomic areas, must be considered for policy formulation. Furthermore, rigorous training of healthcare workers and diversification of their roles could bring about a considerable reduction in the proportion of home deliveries. Birth preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) interventions should be well implemented at the community level to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality by increasing facility-based deliveries [44–46].

Domestic violence and partner control were predisposing factors for home delivery in India. The current study indicated that women who were victims of domestic violence delivered at home more often than women who were not abused. Lack of freedom to go out alone or to visit a healthcare facility could have predisposed women to have more home deliveries. The inherent patriarchal nature of the society, along with the controlling behaviour of men, was reflected here, which denied women decision-making power and prevented them from accessing the healthcare facilities. This could be further explained by the “feminist theory”, which states that gender inequality and men’s entitlement over women are the root causes of domestic violence, which is responsible for poor health among women [31, 47]. Lower status of women in the society as well as in the family could increase the existing burden of home deliveries in India [33]. Therefore, the independence of women, in terms of education, income and decision-making power, is an urgent necessity. A study conducted among the rural women in Rajasthan, India, stated that women who delivered at home experienced higher proportions of severe maternal morbidities in the postpartum period [48, 49]. Interventions to address the staggering number of maternal deaths must be aimed at providing optimum care to the mothers before, during and after childbirth. Provision of incentives to the pregnant mothers and health workers, reduction of out-of-pocket expenditures, transportation facilities and awareness generation must be emphasised. There should be a particular focus on the vulnerable populations, including the women living in more disadvantaged socioeconomic areas to make significant progress towards the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG-3) targets.

The current study incorporated the nationally representative NFHS-4 (2015–2016) data from the states and union territories of India, thereby allowing generalisability of the results. The sampling methodology and data collection instruments used in the study follow the ethical standards for research on women and their health issues, which is asserted by the institutional ethical review boards. Nevertheless, being a cross-sectional study, it is difficult to draw any causal inference. Further longitudinal studies could be carried out in this regard for assigning causality. To know more about why a group of women are delivering at home, several qualitative explorative studies are warranted. The study findings indicated that the prevalence of home deliveries was lower among the women using mobile phones and SMS devices. In-depth qualitative studies are warranted to fully understand this factor for policy formulation.

Conclusion

An interplay of factors such as socio-cultural issues, religious beliefs, lack of knowledge and awareness, and incorrect perceptions of the women could be responsible for the notion that institutional delivery is not necessary. Policymakers should focus more on the women living in more disadvantaged socioeconomic areas and other marginalised populations to provide them with optimum delivery care. Electronic and economic empowerment of women could bring about a remarkable reduction in the proportion of home deliveries in India by increasing their health awareness and decision-making power in the family.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

All the authors wrote and approved the paper. CYO: Drafting, literature support and writing. MY: literature support, review and writing. GU: analysis, writing and critical review. MSL: analysis, writing and critical review. KD: conceptualize, planning, analysis, writing and critical review.

Disclosures

Chung-Ya Ou, Masuma Yasmin, Gainel Ussatayeva, Ming-Shinn Lee and Koustuv Dalal have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The current study was conducted using secondary data from NFHS-4. NFHS-4 had conducted the received ethical approval from the Institutional Ethical Review Board (ref. no./IRB/NFHS-4/01_1/2015) of the IIPS, Mumbai, India. No informed consent was required as this study used anonymized secondary data. However, the field staff and NFHS-4 had received informed consent from all participants.

Data Availability

The study has used NFHS-4 data. Interested readers can contact NFHS-4 for data availability and necessary permission.

References

- 1.Mishra V, Retherford R. The effect of antenatal care on professional assistance at delivery in rural India. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2008;27(3):307–320. doi: 10.1007/s11113-007-9064-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality.

- 3.Efendi F, Ni’mah AR, Hadisuyatmana S, Kuswanto H, Lindayani L, Berliana SM. Determinants of facility-based childbirth in Indonesia. Sci. World J. 2019 (ID 9694602). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kifle MM, Kesete HF, Gaim HT, Angosom GS, Araya MB. Health facility or home delivery? Factors influencing the choice of delivery place among mothers living in rural communities of Eritrea. J Health Popul Nutr. 2018;37(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s41043-018-0153-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gage AD, Carnes F, Blossom J, Aluvaala J, Amatya A, Mahat K, Malata A, Roder-DeWan S, Twum-Danso N, Yahya T, Kruk ME. In low- and middle-income countries, is delivery in high-quality obstetric facilities geographically feasible? Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38(9):1576–1584. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO (2016) World Health Statistics 2016: monitoring health for the SDGS sustainable development goals. World Health Organization, Geneva. https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2016/en/.

- 7.Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–1110. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aday LA, Andersen RM. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Victora CG, Barros AJ, Franca GV, Silva IC, Carvajal-Velez L, Amouzou A. The contribution of poor and rural populations to national trends in reproductive, maternal, new born, and child health coverage: Analyses of cross-sectional surveys from 64 countries. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(4):e402–e407. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30077-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph G, da Silva IC, Wehrmeister FC, Barros AJ, Victora CG. Inequalities in the coverage of place of delivery and skilled birth attendance: analyses of cross-sectional surveys in 80 low and middle-income countries. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0192-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahoo J, Singh S, Gupta V, Garg S, Kishore J. Do socio-demographic factors still predict the choice of place of delivery: a cross-sectional study in rural North India? J Epidemiol Global Health. 2015;5(S1):S27. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yadav AK, Jena PK. Maternal health outcomes of socially marginalised groups in India. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2020;33(2):172–188. doi: 10.1108/IJHCQA-08-2018-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IIPS and ICF . National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index. In: DHS comparative reports no. 6. (Calverton: ORC Macro, 2004).

- 15.Dalal K. Does economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence? J Injury Violence Res. 2011;3(1):35–44. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v3i1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews J, Biswas A, Gifford M, Eriksson C, Dalal K. Identifying households with low immunisation completion in Bangladesh. Health. 2012;4(11):1088–1097. doi: 10.4236/health.2012.411166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aremu O, Lawoko S, Dalal K. Neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage, individual wealth status and patterns of delivery care utilisation in Nigeria: a multilevel discrete choice analysis. Int J Women’s Health. 2011;3:1–8. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S21783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wight RG, Cummings JR, Miller-Martinez D, Karlamangla AS, Seeman TE, Aneshensel CS. A multilevel analysis of urban neighbourhood socioeconomic disadvantage and health in late life. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(4):862–872. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vora K, Mavalankar D, Ramani K, Upadhyaya M, Sharma B, Iyengar S. Maternal health situation in India: a case study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009; 27(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mohanty S, Srivastava A. Out-of-pocket expenditure on institutional delivery in India. Health Policy Plan. 2012;28(3):247–262. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Population Policy New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. 2000;2000:39. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thind A, Mohani A, Banerjee K, Hagigi F. Where to deliver? Analysis of choice of delivery location from a national survey in India. BMC Public Health. 2008; 8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Uthman OA, Amouzou A. Why some women fail to give birth at health facilities: a comparative study between Ethiopia and Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0196896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagchi T, Das A, Dawad S, Dalal K. Non-utilization of public healthcare facilities during sickness: a national study in India. J Public Health. 2020.

- 25.Das J, Hammer J, Leonard K. The quality of medical advice in low-income countries. J Econ Perspect. 2008;22(2):93–114. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mpembeni RN, Killewo JZ, Leshabari MT, Massawe SN, Jahn A, Mushi D. Use pattern of maternal health services and determinants of skilled care during delivery in Southern Tanzania: implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanton C, Blanc AK, Croft T, Choi Y. Skilled care at birth in the developing world: progress to date and strategies for expanding coverage. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39:109–120. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakraborty N, Islam MA, Chowdhury RI, Bari W, Akhter HH. Determinants of the use of maternal health services in rural Bangladesh. J Health Promotion. 2003;18:327–337. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dag414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalal K, Lindqvist K. A national study of the prevalence and correlates of domestic violence among women in India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2010;24(2):265–277. doi: 10.1177/1010539510384499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO . World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalal K. Causes and consequences of violence against child labour and women in developing countries. Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krantz G. Violence against women. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2002;56:242–243. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.4.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keelery S. Estimated public health expenditure in India FY 2017–2020. Health and Pharmaceuticals. 2020.

- 34.Puthuchira Ravi R, Athimulam KR. Does socio-demographic factors influence women’s choice of place of delivery in rural areas of Tamil Nadu state in India? Am J Public Health Res. 2014;2(3):75–80. doi: 10.12691/ajphr-2-3-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra S, Mohanty S. Out-of-pocket expenditure and distress financing on institutional delivery in India. Int J Equity Health. 2019; 18(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Rowland J. Questioning empowerment: working with women in Honduras. Oxford: OXFAM; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Risling T, Martinez J, Young J, Thorp-Froslie N. Evaluating patient empowerment in association with eHealth technology: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(9):e329. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calvillo J, Román I, Roa L. How technology is empowering patients? A literature review. Health Expect. 2013;18(5):643–652. doi: 10.1111/hex.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widmer M, Betran A, Merialdi M, Requejo J, Karpf T. The role of faith-based organisations in maternal and new born health care in Africa. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114(3):218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leonard K. When both states and markets fail: asymmetric information and the role of NGOs in African health care. Int Rev Law Econ. 2002;22(1):61–80. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8188(02)00069-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El Arifeen S, Christou A, Reichenbach L, Osman F, Azad K, Islam K. Community-based approaches and partnerships: innovations in health-service delivery in Bangladesh. Lancet. 2013;382(9909):2012–2026. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehrotra S, Jarrett S. Improving basic health service delivery in low-income countries: ‘voice’ to the poor. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(11):1685–1690. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duong D, Binns C, Lee A. Utilisation of delivery services at the primary health care level in rural Vietnam. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(12):2585–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agarwal S, Sethi V, Srivastava K, Jha P, Baqui A. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among slum women in Indore City, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2010; 28(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Soubeiga D, Gauvin L, Hatem M, Johri M. Birth preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) interventions to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014; 14(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Kesterton A, Cleland J, Sloggett A, Ronsmans C. Institutional delivery in rural India: the relative importance of accessibility and economic status. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010; 10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Keel R. Power-control and feminist theories, 2005. https://www.umsl.edu/~rkeel/200/powcontr.html.

- 48.Iyengar S, Iyengar K, Suhalka V, Agarwal K. Comparison of domiciliary and institutional delivery-care practices in rural Rajasthan, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009; 27(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Iyengar K. Early postpartum maternal morbidity among rural women of Rajasthan, India: a community-based study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012; 30(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The study has used NFHS-4 data. Interested readers can contact NFHS-4 for data availability and necessary permission.