Abstract

Objective:

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is highly comorbid with other substance use disorders (SUDs) as well as other psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). However, studies of persons with AUD rarely account for its comorbidity with other SUDs. Some research suggests that BPD symptoms reflect an important connection between internalizing disorders and SUDs. The current study investigated: 1. The levels of trait anxiety and symptoms of depression and BPD in persons with an AUD as a function of comorbid SUDs (cannabis use disorder – CUD) and other substance use disorder (oSUD), and 2. The influence of BPD on the association between severity of overall lifetime SUD symptoms (AUD + CUD + oSUD) and both trait anxiety and symptoms of depression.

Method:

Trait anxiety and symptoms of depression and BPD were assessed in 671 young adults (351 men; 320 women; mean age 21 years) separated into four groups: Controls (n=185), AUD-only (134), AUD+CUD (n=210), and AUD + oSUD (n=142).

Results:

Trait anxiety and symptoms of depression and BPD were elevated in all AUD groups compared with controls, and in the AUD+oSUD group compared with all other groups as well. Structural models also indicated that BPD symptoms accounted for all of the variance in lifetime SUD symptoms associated with Trait Anxiety, and a significant portion of the variance in lifetime SUD symptoms associated with depression symptoms.

Conclusion.

Results indicate that when AUD is comorbid with oSUD, it is associated with more severe AUD symptoms and higher levels of trait anxiety and symptoms of both depression and BPD. The results also indicate that BPD symptoms account for the majority of the variance in SUD symptoms associated with both trait anxiety and depression, suggesting that a considerable amount of the internalizing symptomatology in AUD /SUDs is associated with BPD psychopathology.

Keywords: Trait Anxiety, Depression, Borderline Personality Disorder, substance use, mental health outcomes, alcohol, cannabis

Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is highly comorbid with other substance use disorders (SUDs) and other psychiatric disorders, such as Borderline Personality Disorder, Major Depression, and Anxiety Disorders (Bailey & Finn, 2019; Bailey, Farmer & Finn, 2019; Eaton et al., 2011; Glass, Williams & Bucholz, 2014; Kessler et al., 1997; Lai et al., 2015; Stinson et al., 2005; Trull et al., 2018). Research also suggests that severe AUD is a risk factor for persistent internalizing disorders (Boschloo et al., 2012). However, studies of the characteristics of persons with AUDs do not always account for its comorbidity with other SUDs and rarely collectively investigate the role of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) symptoms in the comorbid internalizing psychopathology in AUD all in one study. The current study aims to add to the literature by examining the association between comorbid SUDs in individuals with AUD as well as symptoms of internalizing and BPD.

Previous studies show that AUD is strongly associated with depression and anxiety (see Lai et al., 2015 for review), however these studies do not always examine their relation to AUD and comorbid SUDs specifically. To date, one study has examined internalizing psychopathology in persons with AUD as a function of co-occurring other substance use, but not comorbid SUDs (Hedden et al., 2010). Hedden and colleagues (2010) observed that elevated levels of depression and anxiety disorders were associated with nonprescription opiate use or the use of multiple substances, such as marijuana, cocaine, and sedatives. While there are a number of studies of polysubstance use, as opposed to SUDs, that show that the use of more substances tends to be associated with elevated levels of depression, anxiety, or general distress (Connor et al., 2013; Lynskey et al., 2006; Morley. Lynskey, Moran, Borschmann & Winstock, 2015; Quek et al., 2013), there are no other studies of the psychiatric correlates of different patterns of comorbid SUDs in persons with AUD.

Additionally, while studies report high levels of substance use problems in those with BPD (Bailey & Finn, 2019; Eaton et al., 2011; Tomko, Trull, Wood & Sher, 2014; Trull et al., 2018), studies that have examined psychiatric problems as a function of different patterns of co-occurring substance use (i.e., polysubstance) typically do not assess BPD or BPD symptoms (Connor et al., 2013; Hedden et al., 2010; Lynskey et al., 2006; Morley. Lynskey, Moran, Borschmann & Winstock, 2015; Quek et al., 2013). In short, what is missing from this literature is a study that examines the association among AUD, comorbid SUDs, and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and BPD. In addition, although research on comorbidity in BPD consistently shows that BPD is comorbid with AUD and other SUDs (Bailey & Finn, 2019; Eaton et al., 2011; Tomko et al.,, 2014; Trull et al., 2018), there is considerable variation across studies in the percentage of AUD and SUD patients with BPD diagnoses (Trull et al., 2018). There are no studies of the factors associated with varying rates of BPD diagnoses in AUD, and studies typically take a categorical, diagnostic approach to assessing borderline psychopathology, which is less optimal than a dimensional approach (Trull et al., 2018). Thus, the first aim of the current study is to extend this literature by investigating the association between AUD with and without comorbid other SUDs (cannabis use disorder – CUD and other substance use disorder – oSUD) and symptoms of trait anxiety, depression, and borderline personality. We examined these relationships in four different groups that varied in terms of AUD and SUD status. We hypothesized that the AUD/oSUD group would have the most symptoms of depression, anxiety, and borderline personality, followed by more symptom presentation in those with AUD with CUD. We also hypothesized that groups with any SUD would have more severe symptoms than AUD alone.

The second aim of this study is to investigate the nature of the connection between BPD symptoms and the association between anxiety and depression symptoms and SUD severity. While BPD, internalizing disorders, and SUDs are highly comorbid, share common symptomatology, and likely share common etiological processes (Bailey & Finn, 2019; Eaton et al., 2011; Kendler, Prescott, Myers & Neale, 2003; Kendler et al., 2008; Tomoko et al., 2014; Trull et al., 2019), studies have not typically investigated the potential connection between BPD symptoms and internalizing symptomatology in SUDs. Studies suggest that borderline psychopathology may reflect a specific connection between internalizing psychopathology and substance use disorders (Bailey & Finn, 2019; Eaton et al., 2011; Trull et al., 2019). More specifically, BPD is a disorder characterized by both internalizing and externalizing characteristics and the high levels of anxiety and depressive symptomatology in severe SUDs may reflect BPD psychopathology. To explore this hypothesis, using structural equation models (SEMs) we examined the degree to which BPD symptom severity accounted for the variance in SUD severity. In these analyses SUD severity was treated as a single latent variable, or dimension, indexed by lifetime problems with alcohol, cannabis, and any other drug use. We quantified SUD severity as a single latent dimension in these analyses, as research shows that the patterns of problems associated with the use and simultaneous co-use of different substances reflect a single latent spectrum of general substance use and problems (Bailey & Finn, 2020; Derringer et al., 2013).

Materials and Methods

Participants and AUD groups

Recruitment.

The current study analyzed data collected in larger study of behavioral disinhibition in early onset alcohol use disorder that involved the collection of data in multiple domains (e.g., Finn et al., 2009; Finn, Gunn & Gerst, 2015). Participants aged 18 to 30 were recruited through advertisements placed online and around the community in a Midwestern college town. Advertisements targeted a sample that varied in substance use and externalizing problem severity (see Finn et al., 2009; Finn et al., 2015). Advertisements included language targeting heavy drinkers, adventurous and impulsive individuals, social drinkers, and people with a drinking problem with the aim of obtaining a sample with a history of substance use. Other inclusion criteria consisted of the ability to read and speak English, at least a 6th grade education level, no previous history of psychosis or head trauma, and had previously consumed alcohol on at least one occasion. Prior to being interviewed, subjects were administered a breathalyzer to ensure a breath alcohol level of 0.0% and were assessed to determine no drug or alcohol use 12 hours prior to ensure no exclusion criteria were met.

Sample characteristics.

The total sample consisted of 671 participants (320 women, 351 men). The race/ethnicity of the sample was 78.2% Caucasian, 7% African American, 6.1% Asian, 5.5% Hispanic, and 2% other. AUD and other SUD diagnoses were ascertained with the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism – version ii (SSAGA-II) diagnostic interview (Bucholz, Cardoret, & Cloninger, 1994). Individual groups were healthy controls that did not meet any diagnostic criteria (controls, n=185), individuals meeting criteria for an Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) only (AUD only group, n=134), individuals meeting criteria for an AUD + Cannabis Use Disorder only (AUD/CUD group, n=210), and individuals with an AUD and another SUD apart from CUD, referred to as AUD/other Substance Use Disorder (AUD/oSUD) group, n=142). The AUD/oSUD group includes participants with CUD if they had an additional DSM-based diagnosed Stimulant Use Disorder, Opiate Use Disorder, (OUD) Sedative Use Disorder, and Other use disorders. The current study did not break up groups of specific SUDs (e.g., OUD, etc.) due to limited data and power needed to conduct these analyses. Lifetime problems are the total counts of each positive (yes) response to questions in the SSAGA-II diagnostic interview (Bucholz et al., 1994) for each specific substance. Table 1 presents the basic demographic characteristics and the lifetime substance use disorder problems and diagnoses for the sample divided by group. Table 3 (in results) displays the mean lifetime problem counts for alcohol, marijuana and other drugs as well as the percent with lifetime diagnoses of SUD by specific substances.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics and Substance Use Problems and Diagnoses

| Control | AUD Only | AUD + CUD | AUD + oSUD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 185 | 134 | 210 | 142 |

| Sex (M/F) | 80/105 | 54/80 | 124/86 | 93/49 |

| Age M(SD) | 20.70 (2.089)a | 21.07 (1.843)a | 20.86 (2.099)a | 22.46 (3.526)b |

| Education years M(SD) | 14.12 (l.823)c | 14.47 (1.435)c | 14.02 (1.5410b | 13.40 (1.910)a |

| LT Problems M(SD) | ||||

| Alcohol | 2.68 (3.13)a | 20.33 (9.25)b | 22.49 (10.65)b | 30.88 (15.68)c |

| Cannabis | 0.00a | 0.00a | 12.68 (7.31)b | 15.90 (9.85)c |

| Other Substances | 0.00a | 0.00a | 1.35 (3.09)a | 32.72 (28.78)b |

| Diagnoses, % of group | ||||

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 0.00 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Cannabis Use Disorder | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100% | 90.1% |

| Stimulant Use Disorder | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 61% |

| Opioid Use Disorder | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 58.5% |

| Sedative Use Disorder | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 45.1% |

| Other SUD | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 35.9% |

AUD= alcohol use disorder, CUD= cannabis use disorder, oSUD= other substance use disorder. Mean lifetime alcohol counts, lifetime marijuana counts, and mean lifetime count for all other substances. LT= lifetime problems from of positive responses to questions on Alcohol Use Disorder, Cannabis Use Disorder, and other Substance Use Disorder section of SSAGA

c > b > a; p < .001 describes any group differences.

Table 3.

Group Means in Trait Anxiety, Depression Symptoms, and BPD symptoms

| Control | AUD Only | AUD + CUD | AUD + oSUD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait Anxiety M(SD) | 35.37a (7.99) | 40.13b (10.21) | 39.9b (8.64) | 42.40c (10.54) |

| BDI M(SD) | 4.20a (4.38) | 7.06b (5.50) | 6.9b (4.74) | 9.04c (5.25) |

| BPD M(SD) | 1.51a (1.99) | 4.08b (3.11) | 4.6b (3.26) | 5.92c (3.57) |

BDI=depression symptom counts from Beck Depression Inventory, BPD=borderline personality disorder symptom counts from SCID. AUD= alcohol use disorder, CUD= cannabis use disorder, oSUD= other substance use disorder. Mean lifetime alcohol counts, lifetime marijuana counts, and mean lifetime count for all other substances

c > b > a; p < .05 describes any group differences.

Measures

Substance Use Disorder Assessment:

Lifetime AUD and SUD diagnoses and problems were assessed using the SSAGA-II (Bucholz et al., 1994) and DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Those meeting criteria for either alcohol (or other substance) abuse or dependence were assigned an AUD or other SUD (e.g., CUD or other SUD) diagnosis.

Borderline, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptoms:

Symptoms of borderline personality (BPD) were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID: First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin,, 1997) administered in a questionnaire format. This self-report version of the SCID-II BPD section dichotomizes the items into yes or no questions asking whether a participant endorses these types of traits/behaviors in the past several years. SCID-II screening questionnaires have been shown to be highly and reliably correlated with symptoms counts obtained directly from the diagnostic interview (Ekselius, Lindström, von Knorring, Bodlund, & Kullgren, 1994; Jacobsberg, Perry, & Frances, 1995). Trait Anxiety was assessed with the Trait Anxiety Scale of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI: Spielberger & Gorsuch, 1983). Symptoms of depression were measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI: Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). All of these measures were part of the extensive assessment battery for a large study of disinhibition and alcohol problems (e.g., Finn et al., 2015).

Data Analysis

Initial analyses were conducted in SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp, 2017). A two-way Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was used to assess differences (group by sex) in Trait Anxiety, depression symptoms, and BPD Symptoms. LSD post-hoc tests were included to determine differences between group means.

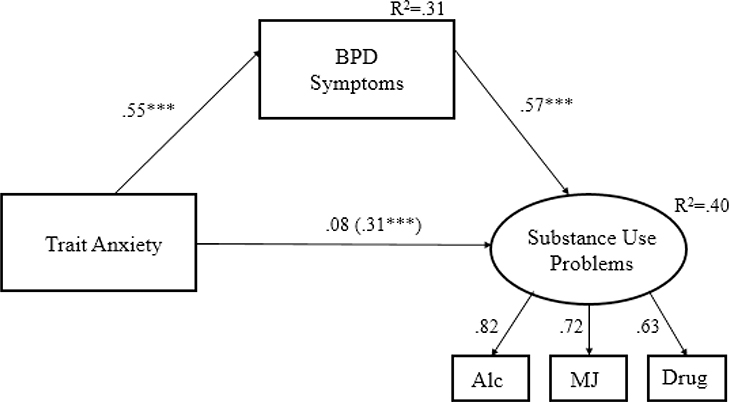

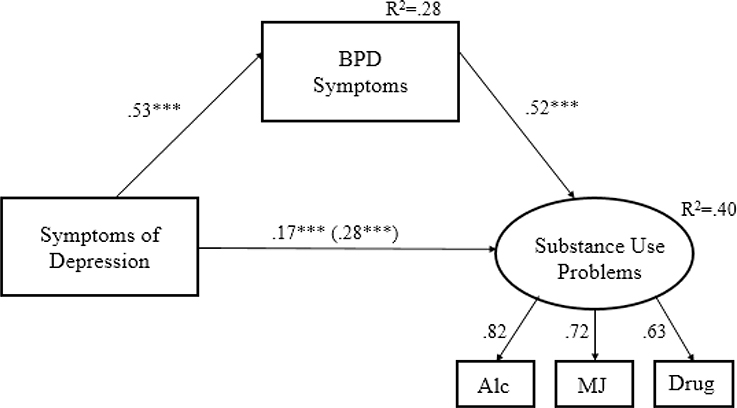

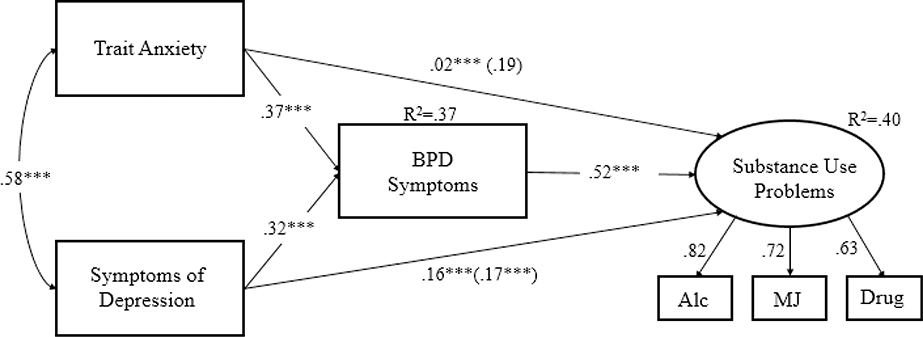

Additional mediation analysis was completed in AMOS version 26 (Arbuckle, 2019). Pearson Product-Moment correlations were conducted to illustrate the significant inter-correlations among all measures and displayed in table 2. Mediation was tested using structural equation modeling (SEMs). Substance use problems were represented as a latent variable, to reflect a general substance use spectrum suggested by previous studies as an appropriate measure of substance use (see Bailey & Finn, 2020), indicated by lifetime problems with alcohol, cannabis, and other substance use. The first model included trait anxiety (exogenous variable), BPD symptoms (as mediator), and lifetime substance use problems (figure 1). The second included depression symptoms as the exogenous variable (figure 2). The third included both trait anxiety and depression symptoms as exogenous variables (figure 3). Each model investigated whether BPD symptoms mediated any of the effects of the exogenous variables on lifetime substance use problems by estimating the direct, indirect, and total effects of each exogenous variable on lifetime substance use problems.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations of Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | - | |||||||

| 2. LT Alc problems | −0.13* | - | ||||||

| 3. LT MJ problems | −0.23*** | 0.57*** | - | |||||

| 4. LT Drug problems | −0.12* | 0.52*** | 0.49*** | - | ||||

| 5. LT Sub problems | −0.18*** | 0.84*** | 0.76*** | 0.87*** | - | |||

| 6. BPD symptoms | −0.04 | 0.53*** | 0.46*** | 0.31*** | 0.50*** | - | ||

| 7. TAI symptoms | 0.06 | 0.33*** | 0.28*** | 0.25*** | 0.34*** | 0.55*** | - | |

| 8. BDI symptoms | 0.09* | 0.37*** | 0.31*** | 0.28*** | 0.38*** | 0.53*** | 0.58*** | - |

= p<.05

= p < .001.

LT= lifetime (alcohol problems), MJ=marijuana, drug = substances other than alcohol and MJ; Sub=all substances, BPD=Borderline personality disorder; BDI=Beck Depression Inventory (Depression symptoms)

Figure 1. Mediation structural equation model of the association between trait anxiety, borderline personality, and total substance problems.

Single directional arrows represent standard regression weights. Significant paths are denoted. The indirect effects of symptoms of trait anxiety are presented in parentheses. Directional regression paths do not infer causal direction. BPD=borderline personality disorder. Alc=alcohol problem count, MJ= Marijuana/cannabis problem count, Drug= drug problem count. *** = significance at p<.001

Figure 2. Mediation structural equation model of the association between depression, borderline personality, and total substance problems.

Single directional arrows represent standard regression weights. Significant paths are denoted. The indirect effects of symptoms of depression are presented in parentheses. Directional regression paths do not infer causal direction. BPD=borderline personality disorder. Alc=alcohol problem count, MJ= Marijuana/cannabis problem count, Drug= drug problem count. *** = significance at p<.001

Figure 3. Mediation structural equation model of the association between symptoms of depression and trait anxiety, borderline personality as mediator, on total substance problems.

Single directional arrows represent standard regression weights. Significant paths are denoted. The indirect effects of trait anxiety and symptoms of depression are presented in parentheses. Directional regression paths do not infer causal direction. BPD=borderline personality disorder. Alc=alcohol problem count, MJ= Marijuana/cannabis problem count, Drug= drug problem count. *** = significance at p<.001

Results

Group Characteristics

There were significant group differences in age, (F(3,633) = 16.25, p<.001), and years of education (F(3,633) = 7.32, p<.001). Table 1 displays these data. The AUD+oSUD was significantly older than all other groups (p <.001) and had fewer years of education compared to all other groups (p < .001). The AUD+CUD group also had significantly fewer years of education than the AUD only group (p=.019). Significant group differences also were observed for lifetime AUD problem counts, F(3,663) = 211.25, p<.001). The AUD+oSUD group had significantly more lifetime AUD problems compared with all other groups (p<.001). The AUD+oSUD group had significantly more lifetime problems with cannabis compared with the AUD+CUD group, t(242.9)= −3.331, p<.001. Table 3 displays the group mean values for these effects.

Trait anxiety and symptoms of depression and BPD

A two-way (group by sex) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to assess group differences in symptoms of depression, BPD symptoms, and trait anxiety. The analysis revealed a significant multivariate main effect of group (Pillai’s Trace= .239, F(9, 1980) = 19.027, p<.001, partial eta squared= .080) and a significant main effect of Sex (Pillai’s Trace= .024, F(3, 658) = 5.342, p=.001, partial eta squared= .024). The Group by Sex interaction was non-significant (Pillai’s Trace= .011, F(9, 1980) = .799, p=.617, partial eta squared= .004).

Main effect of Group.

Univariate analyses revealed significant main effects of Group on symptoms of depression (F(3, 665) = 26.703, p<.001, partial eta squared=.108), trait anxiety (F(3, 665)= 17.014, p<.001, partial eta squared=.071), and BPD symptoms (F(3, 665)= 63.877, p<.001, partial eta squared=.224). Post-hoc LSD tests of differences between group means revealed that controls had significantly lower scores on each measure compared with all AUD groups (ps < .001) and the AUD/oSUD group had significantly higher scores on all measures compared with all other groups (ps < .05). There were no significant differences between the AUD only group and AUD/CUD group (p > .05). Table 3 lists the mean values for each group for all three dependent measures and notes the group differences.

Main effects of Sex:

Univariate analyses revealed significant main effects of sex on trait anxiety (F(1,694)=8.211, p=.004) and depression symptoms (F(1,344)=14.362, p<.001). Females had higher scores on the trait anxiety measure (39.86±9.661 versus 38.66±9.459) and the measure of symptoms of depression (7.14±5.195 versus 6.20±5.2). There were no sex differences on the measure of BPD symptoms (F(1,15)=1.739, p=.188; females=4.03±3.314 versus males=3.80±3.509).

Mediation analyses

The first mediation model (trait anxiety, BPD symptoms, and substance use problems) displayed in Figure 1 fit the data adequately, χ2 (4) =20.690, p=.000, CFI = 0.984, RMSEA = .079. The model revealed significant total effects (β=.40; 95% CI [.04, .07] p<.001) and indirect effects (β=.31; 95% CI [.032, .051] p<.001) of trait anxiety on substance use problems via borderline personality. There was an insignificant direct effect (β=.085; 95% CI [.000, .02], p=.053) of trait anxiety. As illustrated in Figure 1, trait anxiety was significantly associated with BPD (p<.001) and BPD symptoms were significantly associated with substance use problems (p <.001). Figure 1 displays the standardized regression coefficients for all paths, with the indirect effect in parentheses. Overall, the model indicates that BPD symptoms accounted for all of the significant effects of trait anxiety on substance use problems.

The second mediation model (depression symptoms, BPD symptoms, and substance use problems), displayed in Figure 2, adequately fit the data, χ2 (4) =20.226, p=.000, CFI = .984, RMSEA = .078. The model revealed significant total effects (β=.48; 95% CI [.086, .13] p<.001), direct effects (β=.17; 95% CI [.019, .064] p<.001), and indirect effects (β=.28; 95% CI [.052, .085] p<.001) of depression symptoms on substance use. As illustrated in Figure 2 depression symptoms also were significantly associated with BPD symptoms (p < .001) and BPD symptoms were significantly associated with substance use problems (p<.001). This model suggests that BPD partially mediated the association between depression symptoms and substance use problems.

The third model (depression symptoms and trait anxiety, BPD symptoms, and substance use problems) fit the data adequately χ2 (6) =21.34, p=.002, CFI = .989, RMSEA = .062. Essentially, this model (Figure 3) confirms the results of the separate mediation models above. When controlling for depression symptoms, the unique effects of trait anxiety on substance use problems were mediated entirely by BPD symptoms, indirect effect (β = .19, p=.69). In addition, the unique effects of depression symptoms on substance use problems were partially mediated by BPD symptoms with both significant direct effects (β=.16, p<.001) and indirect effects (β=.17, p<.001) of depression symptoms on substance use problems.

Discussion

The overarching goal of the current study was to investigate the relationship between AUDs, comorbid SUD, and internalizing psychopathology and explore the mediating role for BPD symptom severity in the association between internalizing symptoms in SUDs. We first investigated the association between AUDs, trait anxiety, symptoms of depression, and symptoms of BPD, in the context of comorbid SUD. The results indicated that while all AUD groups had elevated levels of trait anxiety, symptoms of depression, and BPD relative to controls, the AUD group with comorbid other substance use disorder (oSUD) had significantly elevated scores in each symptom domain compared with the other two AUD groups (i.e., AUD alone and AUD + CUD). These results are generally consistent with Hedden et al’s (2010) study of the correlates of co-occurring other substance use in AUDs, and other studies of different patterns of polysubstance use (Connor et al., 2013; Lynskey et al., 2006; Morley et al., 2015; Quek et al., 2013). The current study is unique, though, in its inclusion of BPD symptoms. Additionally, we aimed to investigate the role of BPD symptoms in the association between internalizing psychopathology (trait anxiety and symptoms of depression) and overall SUD severity. The results indicate that BPD symptoms account for the majority of the association between both trait anxiety and symptoms of depression on overall SUD symptom severity. This suggests the possibility that elevated trait anxiety and symptoms of depression in persons with substance use disorders may reflect aspects of borderline psychopathology.

Apart from some reports of the co-occurrence of AUD and polysubstance use (Hedden et al., 2010) and the co-occurrence of alcohol use and other substances (Quek et al., 2013), reports rarely investigate the association between psychopathology and comorbidity of AUD with other SUDs. Previous studies focused on the association between measures of psychological distress and different types of illicit drug users derived using latent class analyses of patterns of polysubstance use (e.g., Connor et al., 2013, Lynskey et al., 2006; Morley et al., 2015; Quek et al., 2013). Nonetheless, our results are very similar to the general findings in studies of correlates of polysubstance use. Greater comorbidity among SUDs (i.e., the AUD+oSUD group), or the co-use of additional substances, is associated with higher levels of symptoms of anxiety and depression. Our results extend this literature to include elevated levels of BPD symptoms. Our results and those of the studies of polysubstance use (e.g., Connor et al., 2013, Lynskey et al., 2006; Morley et al., 2015; Quek et al., 2013) suggest that the use, and especially the co-use, of substances such as opiates, cocaine, and benzodiazepines, is indicative of indicate of a more severe type of SUD. In fact, Bailey and colleagues (2019) reported that the co-use of alcohol cannabis, stimulants, sedatives, and opiates, especially the simultaneous co-use of any two substances, was associated with increased addiction severity, overdoses, and negative drug interactions. Of notable interest is the finding that the AUD only and AUD+CUD groups did not differ on measures of anxiety, depression, or borderline personality symptoms. Based on the assumption that more SUD problems are worse than fewer, we expected the AUD+CUD group to have more severe internalizing and borderline symptoms. It could be that the generally young age of participants may be partly responsible for this finding insofar as cannabis use is more prevalent in 20 year-olds (Schulenberg et al., 2018) and, over the longer term, continuing to abuse both alcohol and cannabis into later adulthood may lead to greater psychopathology or reflect more severe psychopathology.

What perhaps is more interesting is our finding and symptoms of BPD accounted for all the association between trait anxiety and severity of lifetime SUD symptomatology, and a substantial portion of the association between symptoms of depression and lifetime SUD symptoms. The high comorbidity of internalizing disorders with AUD and other SUDs is well documented (e.g., Boschloo, et al., 2012; Briere et al., 2014; Lai et al., 2015) as is the high level of comorbidity among BPD, SUDs, and internalizing psychopathology (Bailey & Finn, 2019; Eaton et al., 2011;Tomko et al., 2014; Trull et al., 2018). The current results suggest that BPD symptoms reflect an important mechanism, or link between severity of substance use problems and both trait anxiety and depression symptoms. This is consistent with Trull et al.’s (2018) argument for the important role that BPD plays in the link between internalizing and externalizing disorders. One possible interpretation of these results is that elevated levels of general anxiety and depressive symptomatology in persons with SUDs may reflect aspects of borderline personality psychopathology. Furthermore, since we assessed BPD symptomatology in a dimensional manner, such individuals may not necessarily meet criteria for a diagnosis of BPD but may show some less severe manifestations of borderline psychopathology.

The clinical relevance of these results is that when clients/patients arrive for AUD treatment, additional SUD diagnoses beyond just CUD may indicate more severe psychopathology in general, including both borderline and internalizing symptoms. This result is generally consistent with the literature on polysubstance use where the use of multiple substances is associated with more severe mental health problems (Connor et al., 2013; Hedden et al., 2010; Lynskey et al., 2006; Morley et al., 2015; Quek et al., 2013). Additionally, these results strongly suggest the value of assessing BPD and considering less severe, sub-diagnostic, manifestations of borderline personality in substance users. The presence of borderline psychopathology may indicate additional treatment interventions.

The present study should be interpreted considering its limitations. First, the sample in this study was comprised of mostly white, young adult college students. Second, the sample was recruited based on AUD status. The original recruitment strategy did not specifically target persons with a CUD or other SUD. Thus, our results are best generalizable to relatively high functioning young adult individuals with an AUD diagnosis. Third, the data are cross-sectional and causal interpretations cannot be made regarding the association between AUD status and trait anxiety, symptoms of depression, and symptoms of BPD. Finally, this study leaves open the question about which aspects of BPD account for the association between internalizing symptoms and SUD symptoms. Future research should include more refined measures of the negative affectivity/emotional instability, impulsivity/risk-taking, identity disturbances, and relationship instability domains of BPD to investigate the nature of the connection between BPD, internalizing psychopathology, and SUDs.

In summary, the results clearly suggest that in young adults the co-occurrence of AUD with other SUDs beyond CUD is associated with more severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, and borderline personality. Although these results are not surprising, there are no studies that specifically investigate the association between AUD and comorbid SUDs and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and borderline personality. Further, this result suggests that persons with the combination of a diagnosis of AUD and SUD beyond a CUD are also likely to suffer from higher levels of anxiety, depression, and borderline personality symptoms. Future work should continue exploring poly-, multiple-, or severe substance use as it relates to internalizing and BPD symptoms in ways not specified here. For example, given the current opioid epidemic, future studies may be interested in exploring high severity substance abuse, such as opioid use disorder or groupings of opioid and other substance use, in those with comorbid internalizing or borderline psychopathology. In conclusion, these results suggest an important role of symptoms of borderline personality in the elevated internalizing symptoms in persons with more severe SUDs.

Highlights.

Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and borderline were investigated in an AUD sample.

Four groups were included: controls, AUD only, AUD/CUD, and AUD/oSUD.

The AUD/oSUD group presented with significantly more symptoms.

BPD accounted for all variance in SUD symptoms associated with trait anxiety.

BPD accounted for some variance in SUD symptoms associated with depression.

Results suggest comorbidity of AUD+SUD, and BPD, is associated with more problems.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), R01 AA13650, to Peter R. Finn and by a training grant fellowship to Lindy K. Howe from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) T32 DA024628.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors of this paper declare that they have no conflict of interest relating to the study reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL (2019). Amos (Version 26.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago: IBM SPSS. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AJ, Farmer EJ, & Finn PR (2019). Patterns of polysubstance use and simultaneous co-use in high risk young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AJ, & Finn PR (2020). Examining the utility of a general substance use spectrum using latent trait modeling. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 212, 2020,107998 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A, Finn PR. (2019). Borderline personality disorder: relationship to the internalizing-externalizing structure of common mental disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 33, 1–1430355018 [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, & Erbaugh J (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, van den Brink W, Smit JH, Veltman DJ, Beekman AT, & Penninx BW (2012). Alcohol use disorders and the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(6), 476–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein D, & Lewinsohn PM (2014). Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(3), 526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Schuckit MA (1994). A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 55(2), 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JP, Gullo MJ, Chan G, Young RM, Hall WD, & Feeney GFX . (2013). Polysubstance use in cannabis users referred for treatment: drug use profiles, psychiatric comorbidity and cannabis beliefs. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4, 1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derringer J, Krueger RF, Dick DM, Agrawal A, Bucholz KK, Foroud T, et al. , 2013. Measurement invariance of DSM IV alcohol, marijuana and cocaine dependence between community sampled and clinically overselected studies. Addiction 108, 1767–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Keyes KM., Skodol AE, Markon KE, Grant BF, & Hasin DS (2011). Borderline personality disorder co-morbidity: relationship to the internalizing-externalizing structure of common mental disorders. Psychological Medicine, 41(5), 1041–1050. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekselius L, Lindstrom E, von Knorring L, Bodlund O, & Kullgren G (1994). SCID II interviews and the SCID Screen questionnaire as diagnostic tools for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90(2), 120–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Rickert ME, Miller MA, Lucas J, Bogg T, Bobova L, & Cantrell H (2009). Reduced cognitive ability in alcohol dependence: examining the role of covarying externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(1), 100–116. doi: 10.1037/a0014656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Gunn RL, & Gerst KR (2015). The effects of a working memory load on delay discounting in those with externalizing psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(2), 202–214. doi: 10.1177/2167702614542279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, & Benjamin LS (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV® Axis II Personality Disorders SCID-II. American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Glass JE, Williams EC, & Bucholz KK (2014). Psychiatric comorbidity and perceived alcohol stigma in a nationally representative sample of individuals with DSM 5 alcohol use disorder. Alcohol: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38(6), 1697–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden SL, Martins SS, Malcolm RJ, Floyd L, Cavanaugh CE, & Latmer WW (2010) Patterns of illegal drug use among an adult alcohol dependent population: results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 106, 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsberg L, Perry S, & Frances A (1995). Diagnostic agreement between the SCID—II Screening Questionnaire and the Personality Disorder Examination. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(3), 428–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Czajkowski N, Roysamb E, Tambs K, Torgersen S, Neale MC, & Reichborn-Kjennerud T (2008). The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for DSM-IV personality disorders: a multivariate twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 1438–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, & Neale MC (2003). The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J Anthony JC (1997). Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lai HMX, Cleary M, Sitharthan T, & Hunt GE (2015). Prevalence of comorbid substance use, anxiety and mood disorders in epidemiological surveys, 1990–2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Agrawal A, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Madden PA, Todorov AA, Grant JD, Martin NG, & Heath AC (2006). Subtypes of illicit drug users: a latent class analysis of data from an Australian twin sample. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 9(4), 523–530. doi: 10.1375/183242706778024964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley KI, Lynskey MT, Moran P, Borschmann R, & Winstock AR (2015). Polysubstance use, mental health and high-risk behaviours: Results from the 2012 Global Drug Survey. Drug Alcohol Review, 34(4), 427–437. doi: 10.1111/dar.12263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quek LH, Chan GC, White A, Connor JP, Baker PJ, Saunders JB, & Kelly AB (2013). Concurrent and simultaneous polydrug use: latent class analysis of an Australian nationally representative sample of young adults. Frontiers in Public Health, 1, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, & Goodwin FK (1990). Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA, 264(19), 2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, & Gorsuch RL (1983). State-trait anxiety inventory for adults: sampler set: manual, test, scoring key. Mind Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Huang B, & Saha T (2005). Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 80(1), 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomko RL, Trull TJ, Wood PK, & Sher KJ (2014). Characteristics of borderline personality disorder in a community sample: comorbidity, treatment utilization, and general functioning. Journal of Personality Disorders. 28, 734–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Freeman LK, Vebares TJ, Choate AM, Helle AC, & Wycoff AM (2018). Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: an updated review. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 5, 15. doi: 10.1186/s40479-018-0093-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]