Abstract

Purpose:

Neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC) is an aggressive form of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) for which effective therapies are lacking. We previously identified carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 (CEACAM5) as a promising NEPC cell surface antigen. Here we investigated the scope of CEACAM5 expression in end-stage prostate cancer, the basis for CEACAM5 enrichment in NEPC, and the therapeutic potential of the CEACAM5 antibody-drug conjugate labetuzumab govitecan in prostate cancer.

Experimental design:

The expression of CEACAM5 and other clinically relevant antigens was characterized by multiplex immunofluorescence of a tissue microarray comprising metastatic tumors from 34 lethal mCRPC cases. A genetically defined neuroendocrine transdifferentiation assay of prostate cancer was developed to evaluate mechanisms of CEACAM5 regulation in NEPC. The specificity and efficacy of labetuzumab govitecan was determined in CEACAM5+ prostate cancer cell lines and patient-derived xenografts models.

Results:

CEACAM5 expression was enriched in NEPC compared to other mCRPC subtypes and minimally overlapped with PSMA, PSCA, and Trop2 expression. We focused on a correlation between the expression of the pioneer transcription factor ASCL1 and CEACAM5 to determine that ASCL1 can drive neuroendocrine reprogramming of prostate cancer which is associated with increased chromatin accessibility of the CEACAM5 core promoter and CEACAM5 expression. Labetuzumab govitecan induced DNA damage in CEACAM5+ prostate cancer cell lines and marked antitumor responses in CEACAM5+ CRPC xenograft models including chemotherapy-resistant NEPC.

Conclusions:

Our findings provide insights into the scope and regulation of CEACAM5 expression in prostate cancer and strong support for clinical studies of labetuzumab govitecan for NEPC.

Keywords: labetuzumab govitecan, CEACAM5, ASCL1, pioneer transcription factor, neuroendocrine prostate cancer

Introduction:

While androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is initially effective for the treatment of hormone-sensitive prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), resistance is inevitable and leads to a state known as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). CRPC is heterogeneous and comprises multiple molecular phenotypes that diverge from conventional PRAD and include neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC) which is a high-grade, poorly differentiated, and lethal neuroendocrine carcinoma with no effective treatments. NEPC accounts for up to 20% of lethal metastatic CRPC (mCRPC) and exhibits rapid metastatic dissemination, loss of androgen receptor (AR) signaling, and expression of neuroendocrine differentiation markers. NEPC rarely arises de novo and primarily emerges from PRAD through a process of neuroendocrine transdifferentiation as an adaptive response to the selective pressure of ADT (1).

While an understanding of the determinants of neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate cancer remains incomplete, several genetic alterations have been associated with progression to NEPC. These include loss of the tumor suppressor genes RB1 and TP53, amplification or overexpression of MYCN and AURKA, and activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway (2,3). These genetic derangements are also common to poorly differentiated neuroendocrine cancers arising from other epithelial tissues including the lung. In genetically engineered mouse models, combined loss of Rb1, Trp53, and Pten in the prostate promotes the development of tumors displaying castration resistance, lineage plasticity, and a neuroendocrine cancer phenotype (4,5). Human prostate epithelial transformation models have also underscored the importance of these genetic perturbations in the initiation of NEPC (6,7). Yet neuroendocrine transdifferentiation does not appear to be an obligate outcome of these genetic events in human prostate cancer (8), indicating that other factors may be involved.

In general, NEPC represents an epigenetic cancer state distinct from PRAD with unique patterns of DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility, and epigenetic regulator expression (6,9,10). However, NEPC can vary in histologic appearance and neuroendocrine marker expression, likely due to molecular heterogeneity. Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) shares many phenotypic characteristics with NEPC. Recently, four molecular subtypes of SCLC have been identified, of which two are marked by differential expression and activity of the pioneer neural basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors achaete-scute homologue 1 (ASCL1) and neurogenic differentiation factor 1 (NeuroD1) (11). In a mouse model of SCLC driven by Rb1 and Trp53 loss, Ascl1 but not Neurod1 was required for the initiation of SCLC (12). NeuroD1high SCLC appears to progress from an ASCL1high SCLC state through a process mediated by enhanced MYC expression (13). Given the biological parallels between SCLC and NEPC, these lineage-defining transcription factors may also be operative in NEPC.

The expression of cell surface proteins reflects specific cellular lineage programs in normal development and in cancer. The development of targeted therapies directed against prostate cancer cell surface antigens is an active area of research that must account for the heterogeneity of CRPC phenotypes reflecting diverse cancer differentiation states. Using a systematic approach, we previously identified expression of the human carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 (CEACAM5, also known as CEA) in a large subset of NEPC (14). CEACAM5 is a cell surface protein that is upregulated in a variety of other human epithelial malignancies including colorectal cancer (15) and has been functionally associated with tumor differentiation, invasion, and metastasis (16,17). Multiple therapeutic approaches to target CEACAM5 in cancer are in development including vaccines, bispecific T cell engagers, chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapies, and antibody-drug conjugates (ADC). Labetuzumab govitecan (IMMU-130) is a CEACAM5 ADC composed of a humanized CEACAM5 monoclonal antibody named labetuzumab conjugated to the potent topoisomerase I inhibitor 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN-38) via a unique hydrolysable linker (CL2A) (18). SN-38 is the active metabolite of irinotecan which is commonly used as chemotherapy for colorectal and pancreatic cancer (19). Labetuzumab govitecan has demonstrated activity in preclinical models of colorectal cancer (18,20) as well as safety and potential efficacy in a phase I/II clinical trial in patients with treatment-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (21). However, labetuzumab govitecan has yet to be evaluated in the treatment of prostate cancer.

Here we characterize CEACAM5 expression in end-stage mCRPC relative to other cell surface antigens that are the active clinical focus of diagnostic and therapeutic development. We investigate the molecular basis for CEACAM5 expression in NEPC and uncover insights into the cancer differentiation-specific regulation of CEACAM5. Lastly, we evaluate the antitumor activity of labetuzumab govitecan in preclinical models of CEACAM5+ CRPC, including NEPC, to justify the clinical investigation of this therapeutic agent in prostate cancer.

Materials and Methods:

Cell lines.

DU145 (Cat# DU-145, RRID:CVCL_0105), 22Rv1 (Cat# CRL-2505, RRID:CVCL_1045), C4–2B (Cat# CRL-3315, RRID:CVCL_4784), and NCI-H660 (Cat# CRL-5813, RRID:CVCL_1576) cell lines were purchased from the American Tissue Culture collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA) and LNCaP95 were a gift from Dr. Stephen R. Plymate (University of Washington). All cell lines were validated by short tandem repeat analysis after receipt. DU145, 22Rv1, C4–2B, and MSKCC EF1 (derived from the organoid line MSKCC-CaP4) were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 ug/ml streptomycin, and 4 mM GlutaMAX™. NCI-H660 cells were maintained in Advanced DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with B27, 4 mM GlutaMAX™, and 10 ng/ml recombinant human bFGF and EGF. Cell lines were cultured no more than three weeks after thawing prior to use in described experiments.

mIF of TMAs.

UW mCRPC TAN TMA (Prostate Cancer Biorepository Network) and FDA normal organ TMA (US Biomax Inc.) were used for mIF studies (Tables S1, S2, and S3). Slides were stained on a Leica BOND Rx stainer (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) using Leica Bond reagents for antigen retrieval, antibody stripping (Epitope Retrieval Solution 2), and rinsing after each step (Bond Wash Solution). A high stringency wash was performed after the secondary and tertiary applications using high-salt TBST solution (0.05 M Tris, 0.3 M NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.2–7.6). Opal Polymer HRP Mouse plus Rabbit (PerkinElmer, Hopkington, MA) was used for all secondary applications.

H-scoring of CEACAM5 expression.

H-scores were generated from the CEACAM5 mIF data using the CytoNuclear LC v2.0.6 module and HALO software. Briefly, individual cells were classified as having negative, weak, moderate, or strong CEACAM5 staining and assigned intensity scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The intensity score ranges were defined based on CEACAM5 fluorescent intensity values as follows: 0 = 0 – positive CEACAM5 threshold value, 1 = threshold value – 25th quartile median, 2 = 25th quartile median – 75th quartile median, and 3 = 75th quartile median – maximum value reported. Intensity scores were then multiplied by the percentage of stained cells for a range of 0–300.

Serum CEA quantification.

Cryopreserved serum samples obtained at rapid autopsy or a patient visit prior to rapid autopsy were obtained from the UW TAN repository. CEA quantification was performed using a CLIA-licensed Carcinoembryonic Antigen ELISA test (University of Washington Research Testing Services).

Exome sequencing analysis.

Paired-end exome sequencing (NGS) was performed using Illumina HiSeq or Illumina NovaSeq on genomic DNA isolated from rapid autopsy tissue samples. Sequence reads were aligned to the human reference genome hg19 using the BWA aligner (RRID:SCR_010910). GATK (RRID:SCR_001876) best practice was adopted to process all aligned BAM files. Germline and somatic mutation analyses were performed using HaplotypeCaller and Mutect2. All detected mutations were annotated using ANNOVAR hg19 (RRID:SCR_012821) and manual curation was performed before determination of pathogenicity. Copy number was derived following the standardized Sequenza pipeline (RRID:SCR_016662). All copy number calls were manually curated for potentially missed mid-sized structural aberrations (15–50 nt indels).

C4–2B neuroendocrine transdifferentiation assay.

C4–2B cells were seeded in 6-well tissue culture plates at a density of 105 cells per ml in 3 ml of RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 ug/ml streptomycin, and 4 mM GlutaMAX™. Cells were transduced approximately 4–6 hours after seeding at a defined multiplicity-of-infection of 4 for each lentivirus. Seventy-two hours after transduction, cells were trypsinized, washed, and transferred to 100 mm tissue culture plates in 15 ml of Advanced DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with B27, 4 mM GlutaMAX™, and 10 ng/ml recombinant human bFGF and EGF. Media was replenished every 3–4 days. Cells were collected 11 days post-transduction for analysis.

ATAC sequencing.

Briefly, 50,000 cells were lysed in buffer containing NP-40, Tween-20, and digitonin. Nuclei were collected after centrifugation and transposed with Tn5 transposase for 30 minutes at 37°C. DNA was purified by MinElute Reaction Cleanup Kit (Qiagen) followed by PCR amplification to append indices/adapters, library purification, and quality control by Agilent TapeStation and library quantitation by qPCR. ATAC-seq libraries underwent paired-end 50 bp sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Raw reads were processed with the ENCODE ATAC-seq pipeline (22) for quality control, alignment by Bowtie 2 (RRID:SCR_005476), and peak calling by MACS2 (RRID:SCR_013291). Inferred transcription factor activity was determined by HINT-ATAC (23) using HOCOMOCO (RRID:SCR_005409) and JASPAR (RRID:SCR_003030) binding motifs.

ATAC quantitative PCR.

ATAC-qPCR targeting the CEACAM5 core promoter peak was performed using ATAC libraries on the QuantStudio5 System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with Applied Biosystems PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mean cycle threshold (Ct) obtained for each promoter region was normalized to the AK5 control primers (24).

Immunoblots.

Whole cell extracts were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using a transfer apparatus according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBST (DPBS + 0.5% Tween 20) for 30 minutes while shaking, then incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C for 16 hours. Membranes were washed three times for 5 minutes with PBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were washed three times for 5 minutes each with PBST and developed with Immobilon™ Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (MilliporeSigma) for three minutes at room temperature. Blot images were acquired with a ChemiDocMP Imaging System (Bio-Rad) or autoradiography film.

CEACAM5 surface protein detection by flow cytometry.

DU145, 22Rv1, and MSKCC EF1 cells were dissociated with Versene-EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) into single cell suspensions. Cells were washed once with monoclonal antibody wash buffer (MW; PBS + 0.1% FBS + 0.1% sodium azide) then resuspended in 100 μl MW and 5 μl of anti-CEACAM5-APC or IgG isotype-APC per 106 cells and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes. Cells were washed once with MW, resuspended in MW, acquired on a BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences), and analyzed with FlowJo (v10) (RRID:SCR_008520).

Labetuzumab cell surface binding.

DU145, 22Rv1, and MSKCC EF1 cell lines expressing empty vector or CEACAM5 vector were dissociated non-enzymatically with Versene-EDTA into single cell suspensions. Cells were washed once with PBS and resuspended in 100 ul of 1 ug/ml of h679 or labetuzumab (Immunomedics, Inc.) and incubated at 4°C on ice for 1 hour. Cells were then washed twice with PBS, incubated with an anti-human IgG- PE-Cy5 secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4°C on ice for 30 minutes, washed with PBS, acquired on a SH800 (Sony), and analyzed with FlowJo (v10).

γH2AX detection of dsDNA breaks.

DU145, 22Rv1, and MSKCC EF1 cells were dissociated non-enzymatically with Versene-EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific), washed with PBS, resuspended in PBS and prechilled on ice at 4°C for 20 minutes, followed by incubation with labetuzumab govitecan or h679-SN-38 (Immunomedics, Inc.), or SN-38 (Sigma) for 30 minutes on ice at 4°C. Cells were then washed six times with cold PBS, and cultured for 16 hours in culture media at 37°C. For extended SN-38 treated conditions, cells were cultured at 37°C in media containing SN-38 for 16 hours. Cells were then dissociated with trypsin 0.25%, washed with MW, fixed with BD Cytofixation Buffer (BD Biosciences), permeabilized with BD Phosflow Perm Buffer II (BD Biosciences), and stained with anti-γH2AX-BV421 or IgG isotype control, as per manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were washed twice with MW, resuspended in MW, acquired on a BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences), and analyzed with FlowJo (v10).

SN-38 dose responses in prostate cancer cell lines.

DU145, 22Rv1, MSKCC EF1, and NCI-H660 cells were seeded at 5 × 103 cells (50 μl) per well in 96-well flat bottom, tissue culture treated, white plates (Corning). Cells were treated with serial dilutions of SN-38 (50 μl) in replicates of 8, diluted in appropriate culture media, at 37°C for 96 hours. Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo 2.0 Assay (Promega).

Immunohistochemistry of LuCaP PDX tumors.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were baked at 65°C for 1–2 hours, deparaffinized in xyline, and rehydrated in 100%, 95%, and 70% ethanol. Tissue sections were heated in antigen retrieval buffer (0.2 M citric acid and 0.2 M sodium citrate) within a pressure cooker followed by PBS wash. Tissue slices were blocked with 2.5% horse serum for 30 minutes and then incubated with primary antibody diluted in 2.5% horse serum overnight at 4°C. HRP was detected with ImmPRESS-HRP anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG peroxidase detection kits (Vector Laboratories) and staining was visualized with DAB peroxidase substrate (Dako). Tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and dehydrated for mounting.

Mouse xenograft studies.

All animal care and studies were performed in accordance with an approved Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol and Comparative Medicine regulations. Six-week old, male NSG (NOD-SCID-IL2Rγ-null, RRID:BCBC_4142) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. 5 × 106 cells from each prostate cancer cell line were suspended in 100 μl of cold Matrigel (Corning) and implanted by injection subcutaneously into NSG mice. For LuCaP PDXs, a 1 mm3 piece of prostate tumor tissue was surgically implanted subcutaneously into NSG mice. Mice were enrolled into a treatment arm when tumors reached 150 mm3 and treated by intraperitoneal injection at the frequency and with the doses described. Labetuzumab govitecan and h679-SN-38 doses were prepared fresh through reconstitution with 0.9% preservative-free sodium chloride (McKesson Medical-Surgical). Cisplatin and etoposide (NIH Developmental Therapeutics Program, RRID:SCR_003057) were prepared and stored at room temperature and 4°C, respectively. Mice were monitored biweekly for tumor growth, weight, and body condition score. A complete response is defined as an undetectable tumor.

Complete blood counts and serum chemistries.

Retro-orbital bleeds yielding ~200 μl of blood were performed on mice prior to receiving the first dose at enrollment on day 0, as well as on days 14 and 28 of the study. Blood was collected into green top lithium heparin microcontainers (Becton Dickinson) and tested within 24 hours (Phoenix Labs, Seattle, WA).

Statistical methods.

All data are shown as mean ± SD. For sample sizes less than 40, normality testing was performed with the D’Agostino-Pearson test. For single comparisons, statistical analyses were performed using a two-sided Student’s t-test. For multiple comparisons, statistical analyses were performed using ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc correction. Data not normally distributed were alternatively analyzed using a two-sided Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test or Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA with Games-Howell nonparametric post hoc correction. For correlation analysis, Pearson correlations or Spearman rank correlations were performed for normal and not normal data, respectively. Best fit curves were generated with linear regression modeling. Significance was defined as p≤0.05.

All studies were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines expressed in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Results:

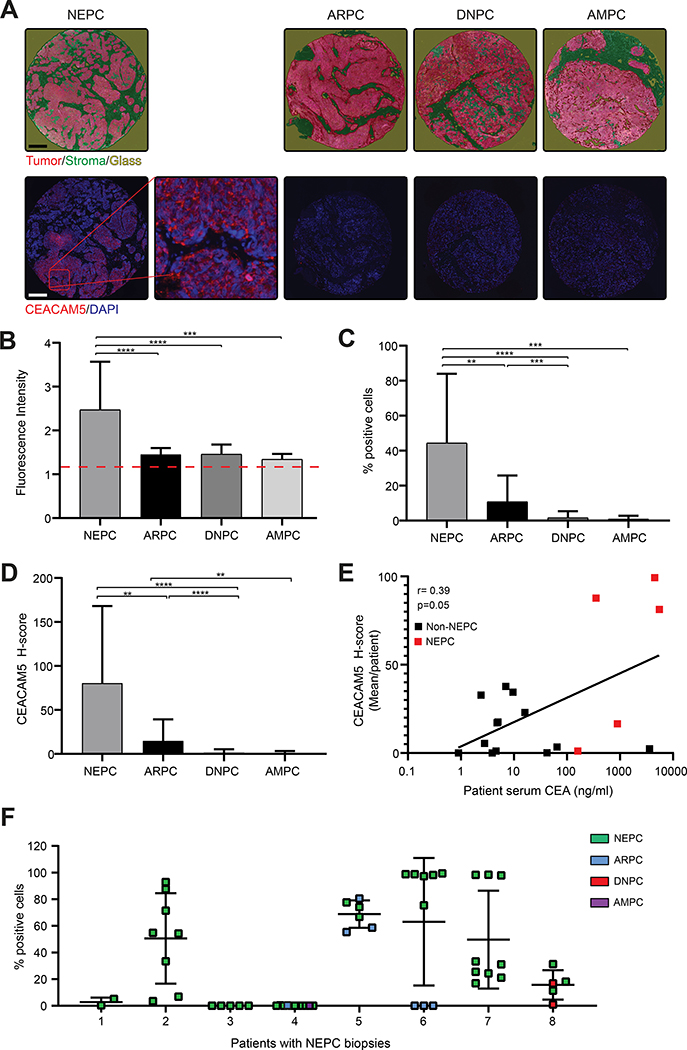

Enrichment of CEACAM5 protein expression in NEPC

To examine CEACAM5 expression across phenotypic subtypes of advanced prostate cancer, we performed immunofluorescence (IF) staining on a clinically and histologically annotated tissue microarray (TMA) of lethal mCRPC tissues from 34 patients collected at rapid autopsy through the University of Washington Tissue Acquisition Necropsy (UW TAN) program (25). Two of 34 patient samples were excluded due to poor quality cores, allowing for the complete analysis of 32 patient tissues. Tissues were classified into four tumor subtypes based on immunohistochemical staining for androgen receptor (AR), prostate-specific antigen (PSA), chromogranin A (ChrA), and synaptophysin (SYP): 1) androgen receptor positive prostate cancer (ARPC: AR+ or PSA+, ChrA−, and SYP−); 2) neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC: AR− and PSA−, ChrA+ or SYP+); 3) double-negative prostate cancer (DNPC: AR−, PSA−, ChrA−, and SYP−); or 4) amphicrine prostate cancer (AMPC: AR+ or PSA+ and ChrA+ or SYP+). Stromal regions of tissue cores were classified based on morphology (Figure 1A) and excluded from all analyses to focus on tumor parenchyma. Image analysis revealed that the overall level of CEACAM5 expression was heightened in NEPC based on fluorescence intensity (Figure 1 B) and that NEPC cores contained significantly more CEACAM5+ cells (44% ± 39.6%) (Figure 1C). Integrated CEACAM5 H-scores (% cells stained x staining intensity) were substantially higher in NEPC (81 ± 87.5) (Figure 1D) compared to other prostate cancer subtypes.

Figure 1. CEACAM5 expression is enriched in the NEPC subtype of mCRPC.

(A) Representative TMA images of individual cores with tumor and stroma annotation as well as fluorescent CEACAM5 (red) and nuclear DAPI (blue) staining (scale bars, 200 μm; original magnification, 20X). (B) Intensity of CEACAM5 staining, (C) percentage of cells with CEACAM5 expression, and (D) H-scores of neuroendocrine (NEPC, n=20), androgen receptor positive (ARPC, n=70), double-negative (DNPC, n=14), and amphicrine (AMPC, n=3) prostate cancers tissue samples. (E) CEA levels in mCRPC patient serum correlated to relative CEACAM5 protein expression (mIF H-score) in corresponding NEPC (n=5) and non-NEPC (ARPC or DNPC) (n=13) patient tumor samples. CEA normal range: 0–5.0 ng/ml. (F) CEACAM5+ cell percentage within the tumor region of cores from all UW mCRPC TAN TMA patient donors with at least one NEPC classified biopsy core. Histograms depict mean + SD. ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001. Red Dash = CEACAM5 staining intensity positive threshold. r=correlation coefficient. Kruskal-Wallis p values are shown for plots C and D. Spearman rank correlation coefficient (r) and p value is shown for plot E.

CEACAM5 expressed on the surface of cells is often shed into the bloodstream and can be measured as serum CEA. Serum CEA is a common clinical cancer biomarker but has had a relatively limited role in the clinical management of prostate cancer. Elevation of serum CEA combined with neuroendocrine tumor marker expression has previously been reported as a clinical criterion for aggressive variant prostate cancer, a spectrum of prostate cancers including NEPC that are molecularly characterized by combined defects in TP53, RB1, and PTEN and respond poorly to AR-directed therapies (26). To explore the relationship between serum CEA levels and tumor CEACAM5 expression in lethal mCRPC subtypes, we assayed banked serum samples collected concurrently with tumor tissue from 18 of the 34 patients represented in the UW mCRPC TAN TMA. We found a significant correlation between serum CEA levels and tumor CEACAM5 expression (r=0.40) based on H-score (Figure 1E). The correlation appeared to be driven primarily by patients with NEPC compared to other mCRPC subsets (Figure S1, A and B) but subgroup analysis was not statistically significant potentially due to limited sample size. These data suggest that serum CEA could be a valuable adjunct clinical biomarker of NEPC and should be investigated further as a part of prospective clinical trials.

Genomic profiling of prostate cancer by next-generation sequencing has identified distinct molecular disease subtypes (27). We performed a limited exploratory analysis of whole exome sequencing of 38 prostate cancer tissues (17 CEACAM5+ and 21 CEACAM5−) from 28 of 34 patients represented on the UW mCRPC TAN TMA. Our analysis focused on a subset of genes commonly altered in mCRPC including RB1 and TP53 and genes in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (Table S). Monoallelic or biallelic copy loss of RB1, TP53, and PTEN appeared to be equally common in CEACAM5+ and CEACAM5− mCRPC tissues, at frequencies consistent with prior reports (8,28). Predicted functional mutations were observed in RB1 and TP53, and the mutational frequency was similar in CEACAM5+ and CEACAM5− tissues. Monoallelic or biallelic copy loss of FOXO3, MAP3K7, and RRAGD was enriched in CEACAM5+ samples compared to CEACAM5− samples by a factor of two. MAP3K7 loss has specifically been reported to promote the development of clinically aggressive prostate cancer, and is associated with AR loss and neuroendocrine differentiation (29).

As tissues were collected from multiple metastatic sites (Tables S1 and S2) and variable CEACAM5 expression was identified within tissues, we next characterized the intra-patient phenotypic heterogeneity of mCRPC in the NEPC samples from the UW mCRPC TAN cohort. Four of eight (50%) patients with NEPC had mixed disease based on the presence of additional histologic phenotypes at other tumor sites (Figure 1F). To evaluate CEACAM5 expression in the context of this intra-patient heterogeneity, we examined all cores from each of these eight NEPC patients. Five of eight patients (62.5%) were found to have CEACAM5+ NEPC (Patients 2, 5, 6, 7, and 8). In these five cases, CEACAM5 expression was present at all NEPC tissue sites, albeit with variability in the frequency of CEACAM5+ cells between sites (Figure 1F). Additionally, the metastatic samples within these five patients that lacked CEACAM5 expression exhibited non-NEPC phenotypes (Figure 1F). These data further demonstrate enhanced CEACAM5 expression in NEPC, not only across a diverse series of patients, but also within patients harboring phenotypically heterogeneous mCRPC.

We also profiled CEACAM5 expression by IF in a normal human organ TMA (Tables S1 and S3). Consistent with prior reports, CEACAM5 expression was detectable at low levels in multiple healthy tissues including the lung, stomach, small intestine, and colon (Figure S2, A–C) (14,30,31). However, the intensity of CEACAM5 staining in normal organs was significantly lower than in NEPC samples represented in the UW mCRPC TAN TMA (Figure 1D). This difference in expression could signify a therapeutic window for agents directed at CEACAM5 when applied to NEPC. Collectively, these results provide a comprehensive assessment of CEACAM5 expression in patients with lethal mCRPC, including NEPC, and in healthy human tissues.

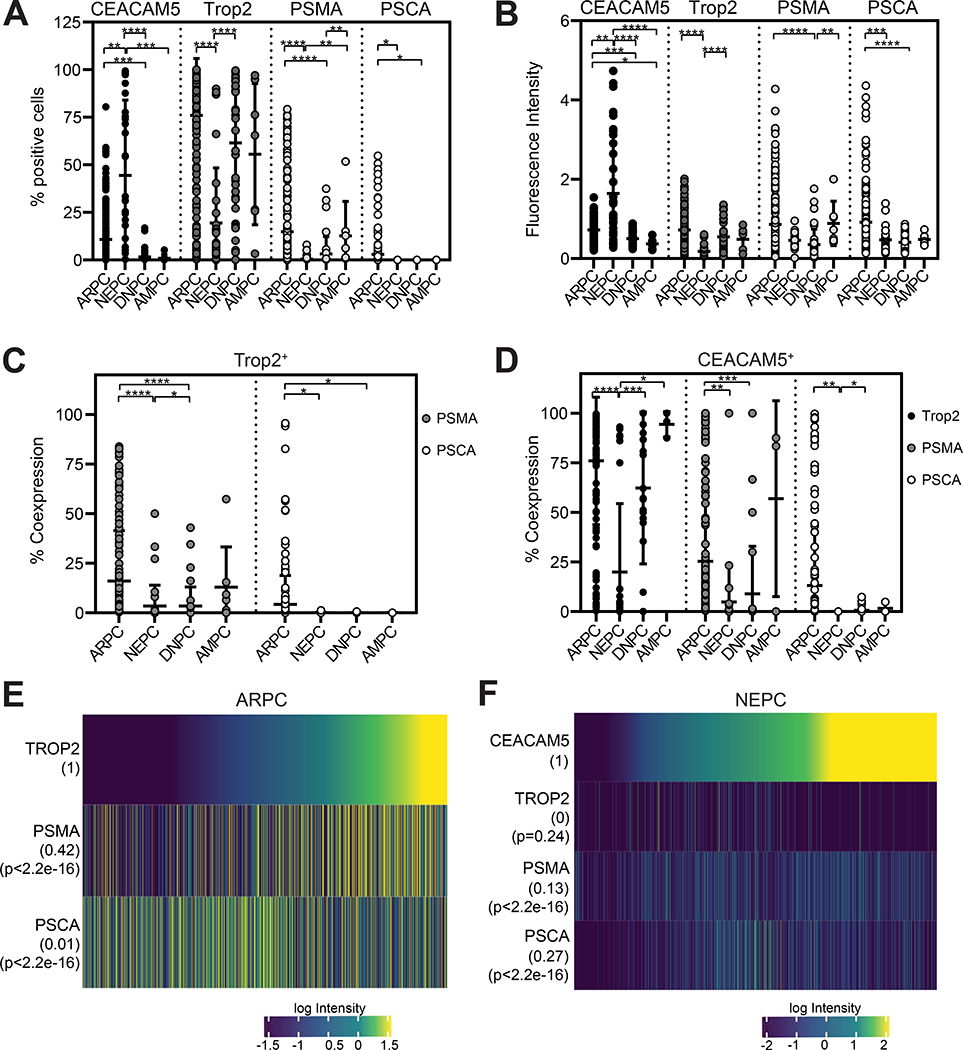

CEACAM5 expression relative to other targetable cell surface antigens in prostate cancer

Multiple clinically relevant prostate cancer antigens including trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (Trop2), prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), and prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA) are the focus of intense clinical development for mCRPC. The Trop2-directed ADC sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132) is currently being evaluated in a phase II study for mCRPC (32). PSMA bispecific T cell engagers, PSMA radioligand therapies, and PSMA and PSCA chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapies are also under clinical investigation for mCRPC. We focused on characterizing the co-expression of CEACAM5 and these prostate cancer antigens in lethal mCRPC using a multiplex IF (mIF) staining panel on the UW mCRPC TAN TMA (Figure S3). mIF image analysis demonstrated inverse patterns of 1) CEACAM5 and 2) Trop2, PSMA, and PSCA staining frequencies and intensities in NEPC and ARPC tissue cores (Figure 2, A and B). Specifically, CEACAM5 expression was enriched in NEPC while Trop2, PSMA, and PSCA expression was heightened in ARPC. Further, PSMA and PSCA were frequently expressed in Trop2+ cores in ARPC but not in NEPC, DNPC, or AMPC (Figure 2C). These results are consistent with the prior characterization of Trop2 as an epithelial marker and the established androgen-regulated nature of PSMA and PSCA expression (33,34). In contrast, Trop2, PSMA, and PSCA were much less frequently expressed in CEACAM5+ cores in NEPC (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. CEACAM5 expression relative to other targetable prostate cancer cell surface antigens.

(A) Percentage of cells expressing CEACAM5, Trop2, PSMA, and PSCA, and (B) staining intensity from mIF of ARPC (n=70), NEPC (n=20), DNPC (n=14), and AMPC (n=3) tissue cores. (C) Co-expression of PSMA and PSCA in Trop2+ cells per core. (D) Co-expression of Trop2, PSMA, and PSCA in CEACAM5+ cells per core. (E) Quantitative single-cell mIF signal intensities of proteins (rows) in cells from ARPC (n=655,676) and (F) NEPC cores (n=113,509). Error bars represent ± SD. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001. Kruskal-Wallis p values are shown for plots A-D. Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and P values for each measured protein is shown numerically next to heatmap rows.

We evaluated mIF data at a single-cell level across all ARPC and NEPC tissue cores to investigate more granular, digital relationships between 1) Trop2, PSMA, and PSCA co-expression in ARPC and 2) CEACAM5, Trop2, PSMA, and PSCA co-expression in NEPC. Trop2 and PSMA (r=0.42) but not PSCA (r=0.01) expression were correlated in ARPC cells (Figure 2E). On the other hand, CEACAM5 did not correlate with Trop2 (r=0) or PSMA (r=0.13) and weakly correlated with PSCA (r=0.27) expression in NEPC cells (Figure 2F). The variable co-expression of Trop2, PSMA, and/or PSCA indicate the presence of highly heterogeneous ARPC cell populations in lethal mCRPC. Further, these findings suggest that diagnostic and therapeutic modalities under investigation to target Trop2, PSMA, and PSCA in prostate cancer may not effectively localize and treat CEACAM5+ NEPC.

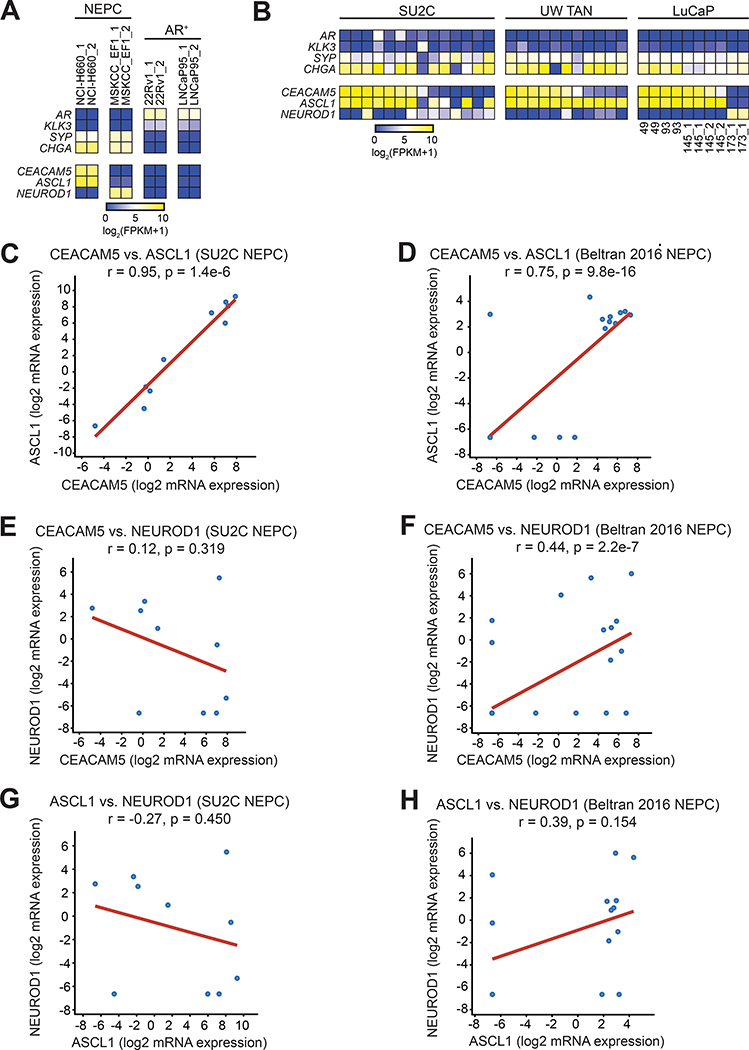

Association between ASCL1 and CEACAM5 expression in NEPC

CEACAM5 is highly expressed in colorectal cancer where prior studies have implicated transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and retinoic acid signaling in CEACAM5 transcriptional regulation (35,36). However, little is known about the regulation of CEACAM5 expression in other cancer types including NEPC. Based on published literature, we discovered that CEACAM5 is expressed in some neuroendocrine carcinomas such as medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) and SCLC but not others like Merkel cell carcinoma (37,38). MTC arises from parafollicular cells which represent calcitonin-secreting neuroendocrine cells of the thyroid that require ASCL1 for their development (39). In SCLC, CEACAM5 expression is specifically enriched in the ASCL1high subtype over other subtypes including NeuroD1high SCLC (Figure S4, A and B). In contrast, Merkel cell carcinoma does not express ASCL1 and instead uniformly expresses NeuroD1 (37,40).

Based on these associations in other neuroendocrine carcinomas, we postulated that ASCL1 may regulate CEACAM5 expression in NEPC. To explore this possibility, we first examined the two available cell line models of NEPC, NCI-H660 and MSKCC EF1. Previously, we have shown that NCI-H660 cells express CEACAM5 and MSKCC EF1 cells do not (14). Transcriptome profiling revealed differential enrichment of ASCL1 in NCI-H660 and NEUROD1 in MSKCC EF1 cells (Figure 3A), consistent with our hypothesis. We further examined gene expression data from Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C) mCRPC biopsies (41), UW mCRPC TAN rapid autopsies (42), and the LuCaP patient-derived xenograft (PDX) series (42) to scrutinize CEACAM5, ASCL1, and NEUROD1 expression in NEPC. Across these three datasets, CEACAM5 expression generally associated with ASCL1 expression but not NEUROD1 expression in NEPC samples (Figure 3B). In the SU2C dataset, CEACAM5 expression was strongly correlated with ASCL1 (r=0.95), but not NEUROD1 (r=0.12) across mCRPC samples demonstrating a neuroendocrine score of >0.4 consistent with NEPC (Figure 3, C and E). The Beltran 2016 NEPC cohort (9) also showed a positive correlation for CEACAM5 and ASCL1 (r=0.75) and interestingly NEUROD1 to a lesser extent (r=0.44) (Figure 3, D and F). The correlation between ASCL1 and NEUROD1 expression was negative (r=−0.27) in the SU2C dataset while the same comparison showed a positive correlation (r=0.39) in the Beltran dataset (Figure 3, G and H). These findings may reflect increased representation of mixed ASCL1high and NeuroD1high NEPC tumors in the Beltran dataset. Of note, Delta-like 3 (DLL3) is a Notch ligand enriched in NEPC (43) that is the target of multiple therapeutics in clinical development for SCLC and is known to be regulated by ASCL1 (44). CEACAM5 expression correlated with DLL3 expression in the SU2C (r=0.54) and Beltran 2016 NEPC (r=0.46) datasets (Figure S5, A and B), suggesting that both genes might be regulated by similar programs.

Figure 3. Association of ASCL1 and CEACAM5 expression in NEPC.

(A) RNA-seq gene expression heatmap of ASCL1 and NEUROD1 in NCI-H660, MSKCC EF1, 22Rv1, and LNCaP95 cell lines. (B) RNA-seq gene expression heatmap of NEPC samples (columns) from the Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C) mCRPC cohort, the University of Washington Tissue Acquisition Necropsy (UW TAN) lethal mCRPC cohort, and LuCaP patient-derived xenograft lines. (C-D) Correlation dot plots of CEACAM5 and ASCL1, (E-F) CEACAM5 and NEUROD1, and (G-H) ASCL1 and NEUROD1 gene expression in NEPC samples defined by a neuroendocrine gene signature score >0.4 in the SU2C dataset (n=10) and the Beltran 2016 NEPC dataset (n=15). Pearson correlation coefficients (r) are shown for correlative gene expression analyses.

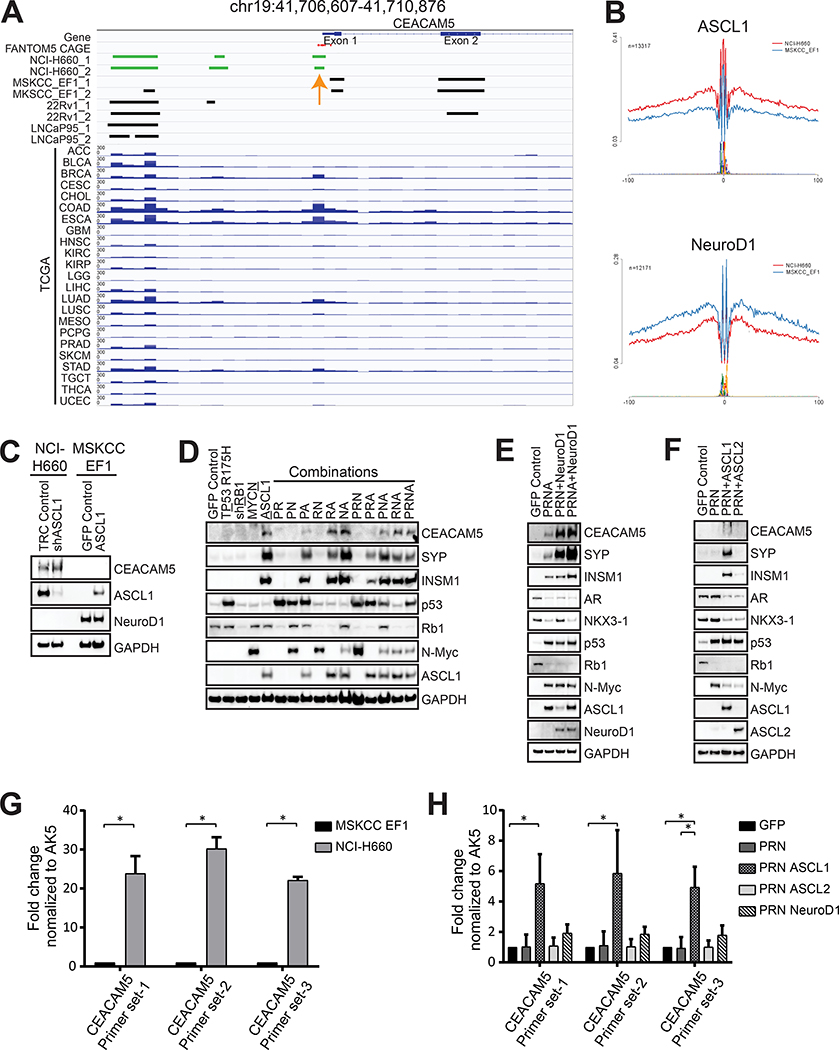

Regulation of CEACAM5 expression during neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate cancer

To uncover possible cis-regulatory elements involved in the transcriptional regulation of CEACAM5 in prostate cancer, we examined chromatin accessibility of the CEACAM5 gene locus using Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) in multiple prostate cancer cell lines, including the NEPC cell lines NCI-H660 and MSKCC EF1 and the AR+ cell lines 22Rv1 and LNCaP95. We identified a differential chromatin accessibility peak located at −191 to −92 upstream of the CEACAM5 transcriptional start site encompassing FANTOM5 Cap Analysis of Gene Expression (CAGE) tags of promoter elements in the CEACAM5+ NCI-H660 cell line but not in the CEACAM5− MSKCC EF1, 22Rv1, or LNCaP95 cell lines (Figure 4A). This peak overlaps with the previously described core promoter region spanning −403 to −124 of the CEACAM5 gene locus (45) and was also prominent in pan-cancer The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) ATAC-seq data (46) in tumor types where CEACAM5 is expressed including colorectal (COAD), esophageal (ESCA), gastric (STAD), and breast cancer (BRCA) (Figure 4A). Consistent with these findings, a coinciding DNase I hypersensitivity site was observed in CEACAM5+ normal colon tissues but not in CEACAM5− normal breast tissues analyzed by the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Project (Figure S6). In addition, the peak heights of the DNase I hypersensitivity site corresponded to reported levels of CEACAM5 expression in colorectal and breast cancer cell lines (Figure S6).

Figure 4. Regulation of CEACAM5 expression during neuroendocrine transdifferentiation.

(A) Integrative Genomics Viewer tracks showing an ATAC-seq peak at the promoter (orange arrow) upstream of the transcriptional start site of CEACAM5. (B) Lineplots demonstrating inferred ASCL1 and NeuroD1 activity in the NCI-H660 and MSKCC EF1 cell lines using differential transcription factor binding motif footprinting of ATAC-seq data. (C) Immunoblots demonstrating CEACAM5 protein expression in NCI-H660 cells with ASCL1 knockdown by shRNA and in MSKCC EF1 cells with ectopic ASCL1 expression. (D) Immunoblots showing CEACAM5 and neuroendocrine differentiation marker expression in C4–2B cells overexpressing ASCL1, (E) NeuroD1, or (F) ASCL2 in the context of p53 R175H, Rb1 knockdown, and/or overexpression of N-Myc. Chromatin accessibility of the CEACAM5 promotor determined by ATAC-qPCR in (G) NCI-H660 cells relative to MSKCC EF1 cells and (H) C4–2B control cells and cells reprogrammed with ASCL1, ASCL2, or NeuroD1. P=p53 R175H; R=shRB1; N=N-Myc; A=ASCL1. Histograms depict means + SD for biological replicates each with two technical replicates. * p<0.05. Student’s T test p values are shown for panel G and Kruskal-Wallis p values are shown for panel H.

Inferred transcription factor binding from ATAC-seq indicated enhanced activity of ASCL1 in NCI-H660 cells and NeuroD1 in MSKCC EF1 cells (Figure 4B) which is in concert with their differential expression in these cell lines. However, functional validation studies with short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of ASCL1 in NCI-H660 cells and ectopic expression of ASCL1 in MSKCC EF1 cells had no discernable effect on CEACAM5 expression (Figure 4C). ASCL1 and NeuroD1 knockdown in the respective NCI-H660 and MSKCC EF1 cells lines was detrimental to cell viability compared to controls (Figure S7, A–C), indicating perhaps that these lines are genetically hardwired and intolerant of perturbations to these transcription factors. The data could also imply that ASCL1 may not regulate CEACAM5 expression through direct transactivation. To corroborate this idea, we examined published ASCL1 chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) data across multiple studies from ASCL1high SCLC cell lines (12,47,48), including the NCI-H889 and NCI-H1755 cell lines which express outlier levels of CEACAM5 (Figure S8A). These analyses indicate the absence of ASCL1 binding peaks near the CEACAM5 gene locus (Figure S8B) but the presence of previously characterized peaks associated with genes bound by ASCL1 such as DLL3 and BCL2 (12,44) (Figure S8, C and D). We therefore hypothesized that ASCL1, as a pioneer neural transcription factor, may epigenetically regulate CEACAM5 by chromatin remodeling. We also reasoned that genetic studies in the hardwired NCI-H660 and MSKCC EF1 NEPC cell lines may not recapitulate dynamic epigenetic regulation of CEACAM5 expression that occurs during the progression of human prostate cancer.

As an alternative approach, we developed a genetically defined system to induce neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate cancer. We introduced ASCL1 and other factors causally associated with neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate cancer including dominant-negative TP53 R175H, shRNA targeting RB1 (shRb1), and MYCN either alone or in combination into the androgen-independent ARPC cell line C4–2B. While C4–2B cells do not express CEACAM5 at baseline, we discovered that all conditions in which ASCL1 was introduced stimulated expression of CEACAM5 and the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin (SYP) and insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1) (Figure 4D). In contrast, all other C4–2B conditions in which ASCL1 was omitted did not exhibit neuroendocrine differentiation (Figure 4D). We discovered that ectopic expression of NeuroD1 within this system also induced CEACAM5, SYP, and INSM1 expression (Figure 4E). Notably, expression of ASCL1 and/or NeuroD1 downregulated AR and AR-dependent NK3 homeobox 1 (NKX3–1) expression (Figure 4E), indicating that these factors may be critical in orchestrating lineage reprogramming from ARPC to NEPC. We also observed that overexpression of NeuroD1 induced ASCL1 expression and the introduction of both ASCL1 and NeuroD1 further enhanced CEACAM5 expression (Figure 4E).

We evaluated a second ASCL family member, ASCL2, in the C4–2B cell line to determine whether these effects may be specific to ASCL1. ASCL2 is also a pioneer transcription factor involved in the specification of multiple lineages including trophectoderm (49), T-helper cells (50), and intestinal stem cells (51). Further, ASCL2 expression is associated with the non-neuroendocrine POU2F3high variant subtype of SCLC (52) and is enriched in multiple cancer types where CEACAM5 is commonly expressed (Figure S9, A–C). Enforced expression of ASCL2, in combination with TP53 R175H, shRB1, and MYCN, in C4–2B cells suppressed AR and NKX3–1 expression, but did not upregulate CEACAM5, SYP, or INSM1 expression (Figure 4F). These data emphasize the differential competence of pioneer transcription factors to effect neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate cancer and induce CEACAM5 expression within this system.

To investigate the epigenetic regulation of the core promoter of CEACAM5 in our C4–2B functional studies, we developed ATAC-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays incorporating universal normalization control primers targeting AK5 and three unique primer pairs targeting the differential chromatin accessible and DNase I hypersensitive site we identified in the core promoter of CEACAM5. The assays were validated using ATAC libraries generated from the NCI-H660 and MSKCC EF1 cell lines (Figure 4G). C4–2B cells reprogrammed with ASCL1 revealed a five-fold enhancement in chromatin accessibility at the core promoter of CEACAM5 relative to control conditions (Figure 4H). In contrast, no increase in chromatin accessibility was associated with ASCL2 and only a minor, non-significant increase was associated with NeuroD1 (Figure 4H). These results point to one mechanism by which neuroendocrine transdifferentiation driven by ASCL1 may be epigenetically linked to CEACAM5 expression in prostate cancer.

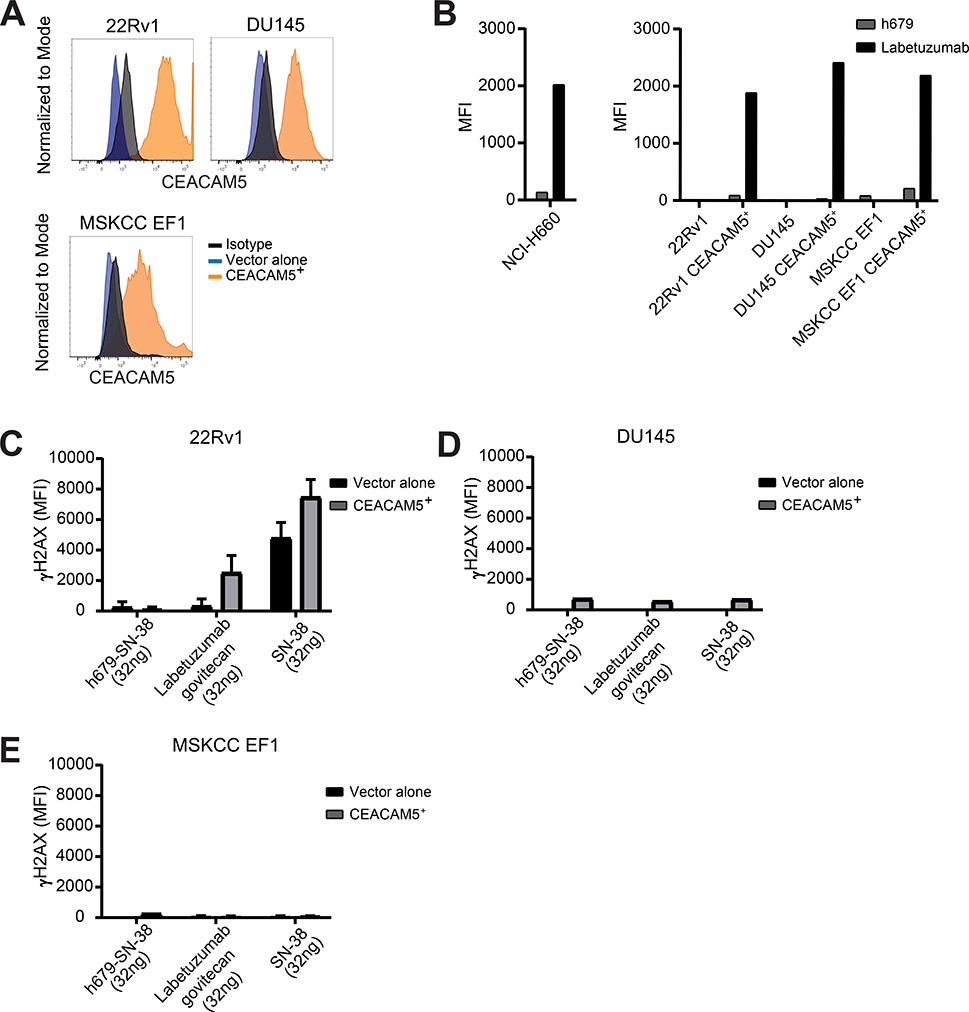

In vitro specificity and cytotoxicity of labetuzumab govitecan in NEPC

We previously reported that a CEACAM5 chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy demonstrates antitumor activity in NEPC cell line models (14). However, we recognized the lengthy time horizon and numerous hurdles to advancing this type of cancer treatment to the clinic. We therefore concentrated on studies to target CEACAM5 in prostate cancer by redirecting the established CEACAM5 ADC labetuzumab govitecan with the anticipation that compelling results could lead to an accelerated path to clinical translation. We first characterized the specific binding of labetuzumab, the humanized antibody component of labetuzumab govitecan, to prostate cancer cell lines with native and engineered expression of CEACAM5. CEACAM5 was stably expressed in three CEACAM5− prostate cancer cell lines: the AR+ line 22Rv1, the AR− line DU145, and the NEPC line MSKCC EF1 (Figure 5A). We detected labetuzumab binding in all four cell lines expressing CEACAM5 as well as the natively CEACAM5+ NCI-H660 cell line, but not in isogenic negative control cell lines (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Labetuzumab govitecan induces dsDNA damage in a CEACAM5-specific manner.

(A) CEACAM5 surface protein expression determined by flow cytometry in prostate cancer cell lines transduced with lentiviral expression constructs. (B) Labetuzumab binding to CEACAM5 in prostate cancer cell lines. Measurement of intracellular γH2AX staining of (C) 22Rv1, (D) DU145, and (E) MSKCC EF1 cells 16 hours after treatment with h679-SN-38, labetuzumab govitecan, or SN-38 for 30 minutes on ice. MFI = Mean fluorescence intensity. Histograms depict means + SD for experimental duplicates.

We then investigated the genotoxic effects of labetuzumab govitecan on the prostate cancer cell line panel by measuring γH2AX, a marker of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) breaks. Cells were incubated with labetuzumab govitecan for 30 minutes, extensively washed to remove unbound drug, and propagated in cell culture for 16 hours prior to staining and analysis. Labetuzumab govitecan provoked greater γH2AX signal in the CEACAM5+ 22Rv1 cell line relative to the control 22Rv1 cell line and compared to incubation with the non-specific ADC, h679-SN-38 (Figure 5C). In contrast, SN-38 alone induced γH2AX in an antigen-independent manner in both the CEACAM5+ and CEACAM5− 22Rv1 cell lines (Figure 5C). H679-SN-38, labetuzumab govitecan, and SN-38 did not generate substantial γH2AX signal in the DU145 and MSKCC EF1 cell lines, irrespective of CEACAM5 expression status (Figure 5, D and E). To determine the overall susceptibility of the cell lines to SN-38, we assessed γH2AX levels following a longer exposure to SN-38 in culture. After a 16 hour incubation, SN-38 induced γH2AX in all three cell lines (Figure S10, A–C), albeit to different extents consistent with drug sensitivity based on IC50 calculations from dose-response curves in each of the cell lines with the exception of DU145 (Figure S10D). These data confirm the specificity of labetuzumab binding and the genotoxicity of labetuzumab govitecan in CEACAM5+ prostate cancer cell lines which generally correlates with the relative sensitivities of the lines to SN-38.

In vivo antitumor activity of labetuzumab govitecan in NEPC

We first examined the antitumor activity of labetuzumab govitecan in vivo using CEACAM5+ NCI-H660 NEPC cell line xenograft tumors established in NOD-scid IL2rγnull (NSG) mice. Mice were treated with labetuzumab govitecan, h679-SN-38, or vehicle by intraperitoneal injections weekly for a total of four treatments over 28 days. By day 17 and day 24, 100% of tumors in the labetuzumab govitecan treatment arm (n=10) and the h679-SN-38 arm (n=9) were undetectable, respectively (Figure S11A). In contrast, tumors in the vehicle treatment arm demonstrated uncontrolled growth (Figure S11A). No significant changes in mouse weight (Figure S11B) or body condition score (Figure S11C) were observed throughout the study at the 25 mg/kg dose. Four of nine (45%) vehicle-treated mice were sacrificed prior to completion of the study as they exceeded institutional tumor size restrictions (Figure S11D).

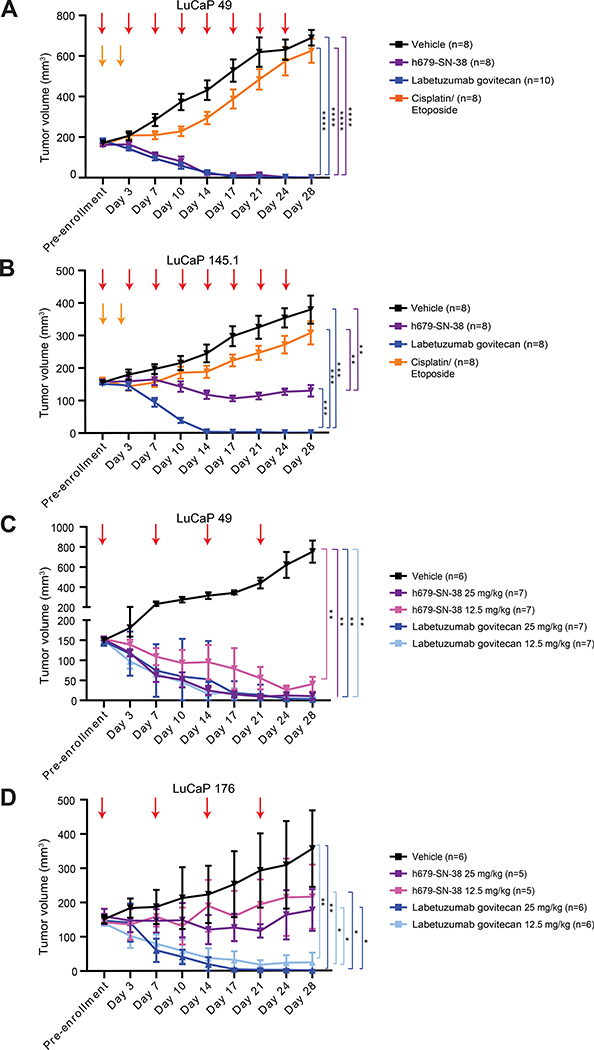

We next tested labetuzumab govitecan treatment in multiple LuCaP PDXs established from lethal mCRPC tissues (53) that express varying levels of CEACAM5. The LuCaP 49 and LuCaP 145.1 NEPC PDXs were classified as CEACAM5low/moderate and CEACAM5high expression models, respectively, based on intensity of immunohistochemical staining (Figure S12). Mice were treated with labetuzumab govitecan or h679-SN-38 at 25 mg/kg or vehicle by intraperitoneal injection every four days. Complete responses were observed in 100% of labetuzumab govitecan (n=10) and h679-SN-38-treated mice (n=8) bearing LuCaP 49 PDX tumors by day 14 (Figure 6A). Complete responses were also observed in 100% of labetuzumab govitecan-treated mice (n=8) with LuCaP 145.1 PDX tumors by day 14, while h679-SN-38 treatment suppressed tumor growth but did not eradicate tumors in any mice (Figure 6B). Importantly, the LuCaP 49 and LuCaP 145.1 tumor models were relatively resistant to cisplatin and etoposide chemotherapy (Figure 6, A and B) which is considered the standard-of-care frontline treatment for extensive stage NEPC.

Figure 6. Labetuzumab govitecan eradicates CEACAM5+ LuCaP PDXs in vivo.

Tumor volumes monitored bi-weekly are shown for (A-B) single dose trials and (C-D) two dose trials. (A-B) Mice received eight treatments (red arrows) over 28 days with vehicle, h679-SN-38 (25 mg/kg), or labetuzumab govitecan (25 mg/kg). Cisplatin (5 mg/kg) was administered on day 0 and etoposide (8 mg/kg) was administered on days 0 and 2 (orange arrows). (C-D) Mice received four treatments (red arrows) over 28 days with vehicle, h679-SN-38, or labetuzumab govitecan at the doses indicated. Line graphs depict means ± SD. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001; **** p<0.0001. Day 28 ANOVA p values are shown for all panels.

In the LuCaP 49 study, the average weight loss in the labetuzumab govitecan group comparing treatment pre-enrollment to day 28 was 10%. However, this weight loss occurred within the first week of treatment and weights otherwise remained stable in all groups for the remainder of the study (Figure S13A). Additionally, no significant changes in body condition scores were observed (Figure S13A). No significant changes in weight or body condition score were observed in mice in the LuCaP 145.1 study (Figure S13B). Adverse effects on liver and kidney function are often reported in association with irinotecan chemotherapy. We performed serum chemistries on days 0, 14, and 28 to assess for these and other toxicities (Figure S14A). Across both studies, three of 18 (17%) labetuzumab govitecan-treated mice exhibited elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels at day 28 that were less than twice the upper limit of the reference range (Figure S14, B and C), indicating mild hepatotoxicity in these animals. Complete blood counts were also performed (Figure S14D). Across both studies, six of 18 (33%) labetuzumab govitecan-treated mice exhibited leukocytosis at day 28 (Figure S14E) with an increase in the neutrophil fraction (Figure S14F). Similar results were observed in the h679-SN-38 and cisplatin and etoposide-treated mice compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure S14D).

Given the striking antitumor effects but mild toxicities associated with labetuzumab govitecan at the 25 mg/kg dose, we tested labetuzumab govitecan at a reduced dose with less frequent dosing. NSG mice bearing CEACAM5low/moderate LuCaP 49 NEPC PDX tumors or CEACAM5high LuCaP 176 ARlow/NE− PDX tumors were treated with labetuzumab govitecan or h679-SN-38 at 25 mg/kg or 12.5 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection weekly. In the LuCaP 49 model, both dose levels of labetuzumab govitecan led to complete responses in 100% of mice (n=7) by day 21. While both dose levels of h679-SN-38 inhibited tumor growth, only the 25 mg/kg dose led to tumor eradication (Figure 6C). The LuCaP 176 model displayed more of a dose-dependent treatment response compared to LuCaP 49. The 25 mg/kg dose of labetuzumab govitecan led to complete responses in 100% of mice (n=6) by day 17. In contrast, tumor eradication was observed in three of six (50%) of mice treated with 12.5 mg/kg of labetuzumab govitecan (Figure 6D). Both dose levels of h679-SN-38 slowed tumor growth but did not diminish tumor volume. No significant changes in weight or body condition score were detected for either study (Figure S13, C and D). These studies highlight the potency and efficacy of labetuzumab govitecan in CEACAM5+ prostate cancer PDX models by demonstrating that a reduced dose and administration schedule are also capable of achieving complete responses.

Discussion:

The development and translation of safe and effective new therapies for NEPC are necessary to alter the course of this highly aggressive and deadly disease. The identification of tumor-restricted cell surface antigens and their targeting with antibodies, ADCs, or adoptive cell therapies has yet to make a clinical impact on the management of NEPC. Recent, substantial efforts have focused on targeting the ASCL1-regulated Notch ligand DLL3, but advanced clinical development of the promising DLL3-targeting ADC rovalpituzumab tesirine was discontinued due to excessive toxicity likely related to the pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer payload (54). Our work indicates that CEACAM5 is a compelling cell surface antigen for therapeutic targeting in NEPC as it is expressed in over 60% of NEPC across multiple cohorts of patients, including those with end-stage disease, and demonstrates limited systemic expression. To accelerate therapeutic development, we redirected the existing CEACAM5-targeted ADC, labetuzumab govitecan, currently being evaluated for metastatic colorectal cancer, to NEPC. In multiple preclinical studies, labetuzumab govitecan treatment of patient-derived CEACAM5-expressing tumors resulted in complete responses. Labetuzumab govitecan is similar in design to the ADC sacituzumab govitecan, which was recently approved for the treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer and has received fast-track designation for metastatic urothelial carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer. Labetuzumab govitecan and sacituzumab govitecan share the same unique hydrolyzable linker, as well as SN-38 as the cytotoxic payload, and have collectively demonstrated manageable toxicities in patients across several clinical studies (21,55,56).

Our studies examining the expression of CEACAM5 and other relevant cell surface antigens in a large cohort of lethal mCRPC samples provide significant biological insights and have important clinical implications. We identified a correlation between serum CEA levels and CEACAM5 expression in tumor tissues across a small series of end-stage mCRPC patients, which appears most prominent in cases of NEPC. The measurement of serum CEA in the appropriate prostate cancer context (e.g. disease progression with a low prostate-specific antigen) might have value for diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes in the identification, treatment selection, and disease monitoring of patients with CEACAM5+ NEPC. Further investigation of serum CEA as a biomarker in clinical trials for NEPC will be necessary to determine its utility. While expression of Trop2, PSMA, and PSCA has been reported to be relatively homogeneous in early stages of prostate cancer, our results indicate that there is significant heterogeneity in their expression in end-stage mCRPC. Our results show that CEACAM5 expression marks a biologically distinct subset of prostate cancer that has relatively minor overlap with Trop2, PSMA, or PSCA expression. The clinical implication is that CEACAM5+ NEPC will not be detected by emerging imaging modalities and may be impervious to treatment approaches directed at Trop2, PSMA, or PSCA.

We also established the functional relevance of ASCL1 and NeuroD1 expression in driving neuroendocrine lineage reprogramming of prostate cancer. These transcription factors appear to induce a simultaneous reduction in AR expression, AR-dependent NKX3–1 expression, and the acquisition of neuroendocrine differentiation markers. Global epigenetic reprogramming of prostate cancer induced by these pioneer transcription factors may coordinately silence the AR-enforced epithelial cancer program and engender neuroendocrine cancer programs. Studies are underway to characterize the contributions of ASCL1 and NeuroD1 to the process of neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate cancer through the integration of genetic, transcriptomic, and epigenetic approaches. Our findings indicate that the biology of NEPC may parallel that of SCLC in that they share ASCL1high and NeuroD1high disease subtypes. However, whether the tuft cell variant POU2F3high or YAP1high subtypes found in SCLC (11) also exist in NEPC has yet to be determined. A recent publication suggests potential biological divergence of NEPC from SCLC in that YAP1 expression is de-enriched in NEPC compared to other subsets of mCRPC (57).

A mechanistic understanding of the regulation of CEACAM5 expression and its specificity to certain cancers has generally been lacking. Previous studies have shown that the wide-ranging modulation of cancer cell differentiation states by retinoic acid or sodium butyrate treatment impacts CEACAM5 expression (36). Our work demonstrates that ASCL1 promotes neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate cancer which results in increased chromatin accessibility of the core promoter of CEACAM5. We suspect that this mechanism of CEACAM5 regulation by ASCL1 may be conserved in other neuroendocrine carcinomas including SCLC, but additional functional studies will be necessary for confirmation. An interesting question arising from our findings is whether additional pioneer transcription factors may similarly modulate the epigenomes of other tumor types to permit CEACAM5 expression in non-neuroendocrine cancer cell contexts.

The diversity of prostate cancer phenotypes that emerge with castration-resistance and their coexistence in late-stage patients indicate that single-targeted therapies may be ineffective. The existence of multiple subtypes of NEPC that may impact expression of target antigens like CEACAM5 and DLL3 in NEPC further compound this issue. Targeted prostate cancer therapies with multiple mechanisms of action or combinations of treatments may be necessary to conquer such diversity. Our in vivo studies demonstrate strong antitumor activity of labetuzumab govitecan and, to a lesser extent, the non-specific h679-SN-38 ADC which is likely a consequence of linker hydrolysis and systemic release of SN-38. Labetuzumab govitecan therefore represents a monotherapy that delivers both regional, antigen-specific and systemic, non-specific tumor killing. The benefit of a moderately stable ADC linker may be increased efficacy in patients with inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity, such as that observed in cases of mixed NEPC which occurs in up to 50% of cases. This bystander effect has also been demonstrated in a number of other tumor types for the sister molecule sacituzumab govitecan (58,59).

The results of these studies have led to planning for a forthcoming phase I/II clinical trial of labetuzumab govitecan for patients with CEACAM5+ NEPC. CEACAM5 is also expressed in other neuroendocrine carcinomas including SCLC and MTC. More than half of SCLC are ASCL1high (11) with the majority expressing CEACAM5, while advanced MTC are almost uniformly ASCL1high and express CEACAM5 (38). Investigation of whether labetuzumab govitecan is effective in these and other CEACAM5+ neuroendocrine carcinomas may also be warranted.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance:

Neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC) is an aggressive subtype of castration-resistant prostate cancer without effective treatments. Here we examined the expression of CEACAM5 compared to other relevant prostate cancer antigens in a series of lethal, metastatic prostate cancers. CEACAM5 is preferentially expressed in NEPC and tumor expression appears to correlate with serum CEA levels in NEPC cases. Through functional genomics studies, we illustrate the potential role of the pioneer transcription factor ASCL1 in the epigenetic regulation of CEACAM5 expression and neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate cancer. Lastly, we redirect the anti-CEACAM5-SN38 antibody-drug conjugate, labetuzumab govitecan, for preclinical studies in prostate cancer and demonstrate tumor eradication in multiple xenograft models of CEACAM5+ prostate cancer including NEPC. Overall, we describe the scope of CEACAM5 expression in end-stage prostate cancer, report a mechanism of CEACAM5 gene regulation by ASCL1, and provide evidence to support imminent clinical investigation of labetuzumab govitecan in men with CEACAM5+ NEPC.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to first and foremost thank the patients and their families for their contributions, without which this research would not have been possible. We acknowledge Celestia Higano, Evan Yu, Heather Cheng, Bruce Montgomery, Elahe Mostaghel, Andrew Hsieh, Daniel Lin, Funda Vakar-Lopez, Xiaotun Zhang, Martine Roudier, Lawrence True, and the rapid autopsy teams for their contributions to the University of Washington Medical Center Prostate Cancer Donor Rapid Autopsy Program. We also thank Serengulam Govindan (Immunomedics, Inc.) for his constructive review of the manuscript. Additionally, we thank Fred Hutch Comparative Medicine for their support and assistance with animal trials, as well as Fred Hutch Experimental Histopathology for their assistance with mIF acquisition and analysis.

Funding: This work was funded by a Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program Awards W81XWH-17-1-0129 (J.K. Lee), W81XWH-18-1-0347 (P.S. Nelson, C. Morrissey), Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award (J.K. Lee), and Immunomedics, Inc. D.C. DeLucia is supported by a Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program Early Investigator Research Award W81XWH-20-1-0119 and a Movember Foundation-Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award. J. K. Lee is also supported by Department of Defense W81XWH-19-1-0758 and W81XWH19-1-0569, a Movember Foundation-Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award, NIH 2P50CA092131 and 5P50CA097186, and Swim Across America. N. De Sarkar is supported by a Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program Early Investigator Research Award W81XWH-17-1-0380. The tissue collection, analysis, and xenograft development was supported by the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Biorepository Network (PCBN) Award W81XWH-14-2-0183 (C. Morrissey, E. Corey, L.D. True), Idea Development Award-Partnering-PI W81XWH-17-1-0414 (C. Morrissey, P.S. Nelson); W81XWH-17-1-0415, the Pacific Northwest Prostate Cancer SPORE award P50CA97186 (P.S. Nelson), an NIH PO1 award PO1 CA163227 (E. Corey, L.D. True, C. Morrissey), the Richard M. LUCAS Foundation, and the Institute for Prostate Cancer Research (IPCR).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: D.C.D. and J.K.L. received research funding from Immunomedics, Inc. T.M.C. was employed by Immunomedics, Inc., and holds stock or stock options in Immunomedics. Inc.

Data and material availability: Raw and analyzed RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data are available at GEO accession number GSE154576. All other materials will be available upon request and completion of a Material Transfer Agreement.

References:

- 1.Beltran H, Hruszkewycz A, Scher HI, Hildesheim J, Isaacs J, Yu EY, et al. The Role of Lineage Plasticity in Prostate Cancer Therapy Resistance. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2019;25(23):6916–24 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-19-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beltran H, Rickman DS, Park K, Chae SS, Sboner A, MacDonald TY, et al. Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine prostate cancer and identification of new drug targets. Cancer Discov 2011;1(6):487–95 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan HL, Sood A, Rahimi HA, Wang W, Gupta N, Hicks J, et al. Rb loss is characteristic of prostatic small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20(4):890–903 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Z, Flesken-Nikitin A, Corney DC, Wang W, Goodrich DW, Roy-Burman P, et al. Synergy of p53 and Rb deficiency in a conditional mouse model for metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2006;66(16):7889–98 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ku SY, Rosario S, Wang Y, Mu P, Seshadri M, Goodrich ZW, et al. Rb1 and Trp53 cooperate to suppress prostate cancer lineage plasticity, metastasis, and antiandrogen resistance. Science 2017;355(6320):78–83 doi 10.1126/science.aah4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JW, Lee JK, Sheu KM, Wang L, Balanis NG, Nguyen K, et al. Reprogramming normal human epithelial tissues to a common, lethal neuroendocrine cancer lineage. Science 2018;362(6410):91–5 doi 10.1126/science.aat5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JK, Phillips JW, Smith BA, Park JW, Stoyanova T, McCaffrey EF, et al. N-Myc Drives Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer Initiated from Human Prostate Epithelial Cells. Cancer Cell 2016;29(4):536–47 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyquist MD, Corella A, Coleman I, De Sarkar N, Kaipainen A, Ha G, et al. Combined TP53 and RB1 Loss Promotes Prostate Cancer Resistance to a Spectrum of Therapeutics and Confers Vulnerability to Replication Stress. Cell Rep 2020;31(8):107669 doi 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beltran H, Prandi D, Mosquera JM, Benelli M, Puca L, Cyrta J, et al. Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Med 2016;22(3):298–305 doi 10.1038/nm.4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clermont PL, Lin D, Crea F, Wu R, Xue H, Wang Y, et al. Polycomb-mediated silencing in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Clinical epigenetics 2015;7:40 doi 10.1186/s13148-015-0074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudin CM, Poirier JT, Byers LA, Dive C, Dowlati A, George J, et al. Molecular subtypes of small cell lung cancer: a synthesis of human and mouse model data. Nat Rev Cancer 2019;19(5):289–97 doi 10.1038/s41568-019-0133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borromeo MD, Savage TK, Kollipara RK, He M, Augustyn A, Osborne JK, et al. ASCL1 and NEUROD1 Reveal Heterogeneity in Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Tumors and Regulate Distinct Genetic Programs. Cell Rep 2016;16(5):1259–72 doi 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mollaoglu G, Guthrie MR, Bohm S, Bragelmann J, Can I, Ballieu PM, et al. MYC Drives Progression of Small Cell Lung Cancer to a Variant Neuroendocrine Subtype with Vulnerability to Aurora Kinase Inhibition. Cancer Cell 2017;31(2):270–85 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JK, Bangayan NJ, Chai T, Smith BA, Pariva TE, Yun S, et al. Systemic surfaceome profiling identifies target antigens for immune-based therapy in subtypes of advanced prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115(19):E4473–E82 doi 10.1073/pnas.1802354115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blumenthal RD, Leon E, Hansen HJ, Goldenberg DM. Expression patterns of CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 in primary and metastatic cancers. BMC Cancer 2007;7:2 doi 10.1186/1471-2407-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashino J, Fukuda Y, Oikawa S, Nakazato H, Nakanishi T. Metastatic potential of human colorectal carcinoma SW1222 cells transfected with cDNA encoding carcinoembryonic antigen. Clin Exp Metastasis 1994;12(4):324–8 doi 10.1007/BF01753839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell E, Shao J, Picon HM, Bristow C, Ge Z, Peoples M, et al. A functional genomic screen in vivo identifies CEACAM5 as a clinically relevant driver of breast cancer metastasis. NPJ Breast Cancer 2018;4:9 doi 10.1038/s41523-018-0062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govindan SV, Cardillo TM, Moon SJ, Hansen HJ, Goldenberg DM. CEACAM5-targeted therapy of human colonic and pancreatic cancer xenografts with potent labetuzumab-SN-38 immunoconjugates. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15(19):6052–61 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weekes J, Lam AK, Sebesan S, Ho YH. Irinotecan therapy and molecular targets in colorectal cancer: a systemic review. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15(29):3597–602 doi 10.3748/wjg.15.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Govindan SV, Cardillo TM, Rossi EA, Trisal P, McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, et al. Improving the therapeutic index in cancer therapy by using antibody-drug conjugates designed with a moderately cytotoxic drug. Mol Pharm 2015;12(6):1836–47 doi 10.1021/mp5006195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dotan E, Cohen SJ, Starodub AN, Lieu CH, Messersmith WA, Simpson PS, et al. Phase I/II Trial of Labetuzumab Govitecan (Anti-CEACAM5/SN-38 Antibody-Drug Conjugate) in Patients With Refractory or Relapsing Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(29):3338–46 doi 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.9011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jinwook Lee DK, Grey Cristoforo, Chuan-Sheng Foo, Chris Probert, Nathan Beley, & Anshul Kundaje. . ENCODE ATAC-seq pipeline (Version 1.5.4). Zenodo 2019. doi 10.5281/zenodo.3564813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Schulz MH, Look T, Begemann M, Zenke M, Costa IG. Identification of transcription factor binding sites using ATAC-seq. Genome Biol 2019;20(1):45 doi 10.1186/s13059-019-1642-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yost KE, Carter AC, Xu J, Litzenburger U, Chang HY. ATAC Primer Tool for targeted analysis of accessible chromatin. Nat Methods 2018;15(5):304–5 doi 10.1038/nmeth.4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roudier MP, True LD, Higano CS, Vesselle H, Ellis W, Lange P, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity of end-stage prostate carcinoma metastatic to bone. Hum Pathol 2003;34(7):646–53 doi 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aparicio AM, Harzstark AL, Corn PG, Wen S, Araujo JC, Tu SM, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy for variant castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19(13):3621–30 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell 2015;163(4):1011–25 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quigley DA, Dang HX, Zhao SG, Lloyd P, Aggarwal R, Alumkal JJ, et al. Genomic Hallmarks and Structural Variation in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cell 2018;174(3):758–69 e9 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodrigues LU, Rider L, Nieto C, Romero L, Karimpour-Fard A, Loda M, et al. Coordinate loss of MAP3K7 and CHD1 promotes aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2015;75(6):1021–34 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klaile E, Klassert TE, Scheffrahn I, Muller MM, Heinrich A, Heyl KA, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-related cell adhesion molecules are co-expressed in the human lung and their expression can be modulated in bronchial epithelial cells by non-typable Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, TLR3, and type I and II interferons. Respir Res 2013;14:85 doi 10.1186/1465-9921-14-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terada T An immunohistochemical study of primary signet-ring cell carcinoma of the stomach and colorectum: III. Expressions of EMA, CEA, CA19–9, CDX-2, p53, Ki-67 antigen, TTF-1, vimentin, and p63 in normal mucosa and in 42 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2013;6(4):630–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lang JM, Kyriakopoulos C, Slovin SF, Eickhoff JC, Dehm S, Tagawa ST. Single-arm, phase II study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of sacituzumab govitecan in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who have progressed on second generation AR-directed therapy. 2020;38(6_suppl):TPS251–TPS doi 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.6_suppl.TPS251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain A, Lam A, Vivanco I, Carey MF, Reiter RE. Identification of an androgen-dependent enhancer within the prostate stem cell antigen gene. Mol Endocrinol 2002;16(10):2323–37 doi 10.1210/me.2002-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright GL Jr., Grob BM, Haley C, Grossman K, Newhall K, Petrylak D, et al. Upregulation of prostate-specific membrane antigen after androgen-deprivation therapy. Urology 1996;48(2):326–34 doi 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han SU, Kwak TH, Her KH, Cho YH, Choi C, Lee HJ, et al. CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 are major target genes for Smad3-mediated TGF-beta signaling. Oncogene 2008;27(5):675–83 doi 10.1038/sj.onc.1210686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niles RM, Wilhelm SA, Thomas P, Zamcheck N. The effect of sodium butyrate and retinoic acid on growth and CEA production in a series of human colorectal tumor cell lines representing different states of differentiation. Cancer Invest 1988;6(1):39–45 doi 10.3109/07357908809077027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corella AN, Cabiliza Ordonio MVA, Coleman I, Lucas JM, Kaipainen A, Nguyen HM, et al. Identification of Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in Small-cell Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26(7):1667–77 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mendelsohn G, Wells SA Jr., Baylin SB. Relationship of tissue carcinoembryonic antigen and calcitonin to tumor virulence in medullary thyroid carcinoma. An immunohistochemical study in early, localized, and virulent disseminated stages of disease. Cancer 1984;54(4):657–62 doi . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanigan TM, DeRaad SK, Russo AF. Requirement of the MASH-1 transcription factor for neuroendocrine differentiation of thyroid C cells. J Neurobiol 1998;34(2):126–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chteinberg E, Sauer CM, Rennspiess D, Beumers L, Schiffelers L, Eben J, et al. Neuroendocrine Key Regulator Gene Expression in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Neoplasia 2018;20(12):1227–35 doi 10.1016/j.neo.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abida W, Cyrta J, Heller G, Prandi D, Armenia J, Coleman I, et al. Genomic correlates of clinical outcome in advanced prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116(23):11428–36 doi 10.1073/pnas.1902651116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Labrecque MP, Coleman IM, Brown LG, True LD, Kollath L, Lakely B, et al. Molecular profiling stratifies diverse phenotypes of treatment-refractory metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Invest 2019;130:4492–505 doi 10.1172/JCI128212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puca L, Gavyert K, Sailer V, Conteduca V, Dardenne E, Sigouros M, et al. Delta-like protein 3 expression and therapeutic targeting in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Sci Transl Med 2019;11(484) doi 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson BR, Hartman BH, Ray CA, Hayashi T, Bermingham-McDonogh O, Reh TA. Acheate-scute like 1 (Ascl1) is required for normal delta-like (Dll) gene expression and notch signaling during retinal development. Dev Dyn 2009;238(9):2163–78 doi 10.1002/dvdy.21848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hauck W, Stanners CP. Transcriptional regulation of the carcinoembryonic antigen gene. Identification of regulatory elements and multiple nuclear factors. J Biol Chem 1995;270(8):3602–10 doi 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corces MR, Granja JM, Shams S, Louie BH, Seoane JA, Zhou W, et al. The chromatin accessibility landscape of primary human cancers. Science 2018;362(6413) doi 10.1126/science.aav1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Augustyn A, Borromeo M, Wang T, Fujimoto J, Shao C, Dospoy PD, et al. ASCL1 is a lineage oncogene providing therapeutic targets for high-grade neuroendocrine lung cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(41):14788–93 doi 10.1073/pnas.1410419111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hokari S, Tamura Y, Kaneda A, Katsura A, Morikawa M, Murai F, et al. Comparative analysis of TTF-1 binding DNA regions in small-cell lung cancer and non-small-cell lung cancer. Mol Oncol 2020;14(2):277–93 doi 10.1002/1878-0261.12608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bogutz AB, Oh-McGinnis R, Jacob KJ, Ho-Lau R, Gu T, Gertsenstein M, et al. Transcription factor ASCL2 is required for development of the glycogen trophoblast cell lineage. PLoS Genet 2018;14(8):e1007587 doi 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu X, Chen X, Zhong B, Wang A, Wang X, Chu F, et al. Transcription factor achaete-scute homologue 2 initiates follicular T-helper-cell development. Nature 2014;507(7493):513–8 doi 10.1038/nature12910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Flier LG, van Gijn ME, Hatzis P, Kujala P, Haegebarth A, Stange DE, et al. Transcription factor achaete scute-like 2 controls intestinal stem cell fate. Cell 2009;136(5):903–12 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang YH, Klingbeil O, He XY, Wu XS, Arun G, Lu B, et al. POU2F3 is a master regulator of a tuft cell-like variant of small cell lung cancer. Genes Dev 2018;32(13–14):915–28 doi 10.1101/gad.314815.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang X, Coleman IM, Brown LG, True LD, Kollath L, Lucas JM, et al. SRRM4 Expression and the Loss of REST Activity May Promote the Emergence of the Neuroendocrine Phenotype in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21(20):4698–708 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poirier JT. IA24 Targeting DLL3 in Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Novel Modalities. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2020;15(2):S8 doi 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bardia A, Mayer IA, Diamond JR, Moroose RL, Isakoff SJ, Starodub AN, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Trop-2 Antibody Drug Conjugate Sacituzumab Govitecan (IMMU-132) in Heavily Pretreated Patients With Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(19):2141–8 doi 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.8297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bardia A, Mayer IA, Vahdat LT, Tolaney SM, Isakoff SJ, Diamond JR, et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy in Refractory Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;380(8):741–51 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1814213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng S, Prieto-Dominguez N, Yang S, Connelly ZM, StPierre S, Rushing B, et al. The expression of YAP1 is increased in high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma but is reduced in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2020. doi 10.1038/s41391-020-0229-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perrone E, Lopez S, Zeybek B, Bellone S, Bonazzoli E, Pelligra S, et al. Preclinical Activity of Sacituzumab Govitecan, an Antibody-Drug Conjugate Targeting Trophoblast Cell-Surface Antigen 2 (Trop-2) Linked to the Active Metabolite of Irinotecan (SN-38), in Ovarian Cancer. Front Oncol 2020;10:118 doi 10.3389/fonc.2020.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeybek B, Manzano A, Bianchi A, Bonazzoli E, Bellone S, Buza N, et al. Cervical carcinomas that overexpress human trophoblast cell-surface marker (Trop-2) are highly sensitive to the antibody-drug conjugate sacituzumab govitecan. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):973 doi 10.1038/s41598-020-58009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.