Abstract

Cantharidin is a potent natural protein phosphatase monoterpene anhydride inhibitor secreted by several species of blister beetle, with its demethylated anhydride analogue, (S)-palasonin, occurring as a constituent of the higher plant Butea frondosa. Cantharidin shows both potent protein phosphatase inhibitory and cancer cell cytotoxic activities, but possible preclinical development of this anhydride has been limited thus far by its toxicity. Thus, several synthetic derivatives of cantharidin have been prepared, of which some compounds exhibit improved antitumor potential and may have use as lead compounds. In the present review, the potential antitumor activity, structure-activity relationships, and development of cantharidin-based anticancer drug conjugates are summarized, with protein phosphatase-related and other types of mechanisms of action discussed. Protein phosphatases play a key role in the tumor microenvironment, and thus described herein is also the potential for developing new tumor microenvironment-targeted cancer chemotherapeutic agents, based on cantharidin and its naturally occurring analogues and synthetic derivatives.

Keywords: Cantharidin, Protein phosphatase, Tumor microenvironment, Structure-activity relationship, Mechanisms of action, Anticancer drug conjugates

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Cancers are complex matrices composed of malignant and non-malignant cells, which create a tumor microenvironment (TME), where the non-malignant cells, including immune cells, tumor vasculature and lymphatic cells, fibroblasts, pericytes, and adipocytes, support the survival of the cancer cells.1 The biology and function of these non-malignant cells are not known fully, but it is clear that communication between the stromal and malignant cells enables cancer cells to invade normal adjacent tissues. Thus, fully understanding the supporting stroma is crucial for the development of novel therapies targeting primary and metastatic tumors.2

The TME is characterized by acidity, hypoxia, increased lactate and reduced glucose concentrations, secretome changes, and recruitment of stromal and immune cells. An extracellular acidity is developed by the deregulated energy metabolism of cancer cells, and this acidic TME promotes cancer progression.3 In turn, interactions with the TME contribute critically to the successful treatment of cancer, and several TME-related targets have been used in the design of new anticancer agents.4 For example, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) immunoreactivity was detected in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), an abundant component of TME, and inhibition of IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) or phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt or PKB)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway was proposed to be beneficial prior to the development of cancer cell resistance to cancer chemotherapeutic agents.5 CAFs were also found to secrete Wingless-related integration site 2 (Wnt2), a secretory glycoprotein to support cancer progression, to induce colorectal cancer (CRC) cell migration and invasion,6 and they are also involved in the modulation of many components of the immune system.7

The hypoxic TME and hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) play important roles in the cellular response to tumor hypoxia, for which HIF-1a regulates the switch from pyruvate catabolism and oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis in both hypoxic and normoxic cells.8 Both cancer and stromal cells undergo rapid metabolic adaptations in the TME, and they need to coordinate metabolically or to compete with each other to meet their biosynthetic and bioenergetic demands while escaping immunosurveillance. Thus, metabolic communications between malignant and non-malignant cells are important in order for cancer cell survival.9

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) that can terminally differentiate into cancer cells maintain their stemness in a specific microenvironment, and they acquire drug resistance from interacting with their stromal cells in the TME, while the stromal cells protect CSCs from the effects of anticancer therapeutic agents.10 CSCs also have immunomodulatory capabilities to avoid host anticancer immunity, and thus they show some immunotherapy resistance in cancer patients.11 In this regard, elimination of the stromal cells would lead to support the killing of CSCs, but this may lead to severe side effects on other normal tissues or organs. Alternatively, hypoxia in the TME is a major stimulus factor that induces angiogenesis and regulates the expression of angiogenic cytokines in a variety of immunosuppressive cells. Induction of angiogenesis results in an abnormal tumor vasculature, and further aggravating hypoxia limits the efficacy of cancer chemotherapies.12 Therefore, hypoxia in TME has emerged as a mechanism to repurpose angiogenic molecules, and normalization of the tumor vasculature and targeting the TME could be an essential strategy to overcome multidrug resistance (MDR) to improve cancer therapeutic outcomes.13 In addition, cancer cells escape the host immune system to survive through the expression of their immune checkpoint proteins, among which the programmed death-ligand-1/programmed death-1 (PD-L1/PD-1) protein affects tumor development and cancer therapy tremendously. Various components in the TME are essential for the modification of the PD-L1 levels, and thus the TME has also become important for immunotherapy and PD-L1/PD 1 blockade therapy.14

In the TME, the cancer cells and the stromal cells communicate with each other via cytokines/chemokines, cell-cell contact, and/or metabolic interactions. These signaling pathways involve dysregulation of protein kinases and protein phosphatases, protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), and serine/threonine protein phosphatases (PP).15,16 PTPs function as a super-family of enzymes and play a causative role in human diseases,15 and PPs target the hypoxia-mediated, Wnt, Notch, and cytokine/chemokine signaling pathways and the cell-to-cell communication and immune surveillance in the TME to support cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy.16 Therefore, all of the major components of TME, such as CAFs, CSCs and related protein kinases, including angiogenic and metabolic molecules and PTPs/PPs, as well the HIF-1, IGF-1/IGF-1R, Notch, PD-L1, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, and Wnt2 signaling pathways could be potential targets for TME-driven antitumor agents.

As a tumor driver, the TME plays a critical role in supporting tumor cell survival from therapeutic challenges and the host’s defense systems, while PPs function critically in the TME, and hence inhibition of PPs could contribute to an optimal treatment of cancer. Cantharidin (CTD, 1) as secreted by the insect, Mylabris phalerata Pallas (Meloidae), has been identified as a potent PP inhibitor and found to show potential antitumor activity.17,18 In the present contribution, the PP-related and TME-targeted potential antitumor activity of CTD is reviewed, with the mechanisms of action and synthetic modifications of this compound being discussed.

2. Protein phosphatase inhibitory and anticancer-related activities of cantharidin

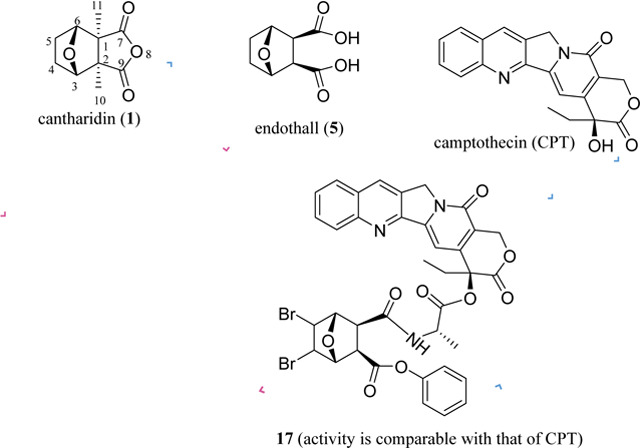

Mylabris, the dried body of the Chinese blister beetle, Mylabris phalerata Pallas (Meloidae), has been used as a traditional Chinese medicine to treat cancer for over 2000 years, with the monoterpene anhydride, cantharidin (CTD, 1), having been characterized as the major active compound (Figure 1). The blister beetle has been found to be toxic, but it does not inhibit bone marrow cell growth, indicating some promise for the development of antitumor leads from the constituents of this organism.19 Interestingly, a mono-demethylated analogue of CTD, (S)-palasonin (2) [(1S,2R,3S,6R)-(S)-palasonin (2)], was isolated from the seeds of the higher plant Butea frondosa Koenig ex Roxb. (Leguminosae),20,21 and this demethylated anhydride (2), along with its enantiomer, (1R,2S,3R,6S)-(R)-palasonin, was also identified from a beetle species, Trichodes apiarius (L.).22 These discoveries represent a very limited case of the isolation of the same general chemical entity from both a plant and insects. Moreover, (1S,2R,3S,6R)-(S)-palasonin (2) and its enantiomer, (1R,2S,3R,6S)-(R)-palasonin, have been synthesized successfully.23

Fig. 1.

Structures and IC50 values (μM) for inhibition of aPP1 and bPP2A of cantharidin (1) and (S)-palasonin (2).

Both CTD (1) and (S)-palasonin (2) were found to inhibit the major serine/threonine-specific protein phosphatases 1 (PP1) and 2A (PP2A), with IC50 values being the range 0.04–0.7 μM, but neither compound showed any activity against PP2C (IC50 >1000 μM) (Table 1 and Figure 1).17 Compounds 1 and 2 exhibited different potencies in terms of the inhibition of PP1 and PP2A, indicating that the C-11 methyl group is important for CTD to interact with PPs. As a potent inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A, CTD was found to be cytotoxic toward human cancer cells,24 but its cantharimide-type analogues isolated also from blister beetles did not show any activity towards the cancer cells utilized (IC50 >10 μM).25–27 This indicated that an intact anhydride unit is important for CTD to mediate its cancer cell cytotoxicity.

Table 1.

Toxicity and PP1 and PP2A inhibition of 1 and selected analogues.

| compound | PP1a | PP2Ab | PP2Cc | LD50d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cantharidin (1)17 | 0.47 | 0.04 | >1000 | 1.0 |

| (S)-palasonin (2) 17 | 0.66 | 0.12 | >1000 | |

| norcantharidin (3)17,93 | 1.9893 | 0.3793 | 4.017 | |

| cantharidic acid (4) 17 | 0.56 | 0.05 | >1000 | 1.8 |

| endothall (5) 17 | 5.0 | 0.97 | >1000 | 14 |

| 9-deoxocantharidin (8)94 | >200 | >200 | ||

| 9-deoxonorcantharidin (9)94 | 62.2 | 99.9 |

IC50 value (μM) for inhibition of aPP1, bPP2A, and cPP2C. dMouse i.p. LD50 (mg/kg).

The potential antitumor activity of CTD has been investigated extensively,18,28–30 and PP2A has been characterized as its molecular target.31,32 For example, CTD and its analogues were found to inhibit both PP1 and PP2A and human cancer cell growth,33,34 and CTD itself induced mitotic arrest through, in part, the suppression of PP2A,35 while several analogues of CTD were found to inhibit PP2B selectively.36 In addition, CTD binds to PP5 to inhibit the activity of this protein, in which the ether oxygen bridge was found to play an critical role in metal binding.37,38 PP5 regulates negatively 5’-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation and contributes to cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) aggressiveness, and thus CTD was found to suppress cell growth through reducing PP5 activity and enhancing AMPK phosphorylation in CCA cells.38

As summarized previously, CTD (1) exhibits a broad spectrum of activity against human cancer cell lines.27 Using Connectivity Map (CMAP), a tool for the elucidation of disease-gene-drug connections with microarrays, CTD was characterized as a lead for the treatment of glioblastoma, the most common adult brain tumor. Further biological investigations showed that CTD inhibited KS-1, SF126, T98G, YH-13 human glioblastoma cell growth and induced apoptosis through increasing cleaved caspase-3, caspase-9, and poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP1) in T98G cells.39 Also, CTD was found to target primary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) stem and progenitor cells to decrease the levels of hepatic leukemia factor (HLF) protein, which induces apoptosis in AML cells, even though CTD seems not to exhibit any therapeutic promise against leukemia.40 Furthermore, CTD was found to suppress the proliferation of human melanoma cells and consequently has been proposed as a lead compound for the treatment of this type of cancer.41

Interestingly, CTD (1) showed inhibitory effects on cancer cell metastasis. It inhibited the cell viability, migration, and invasion and activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2/−9 (MMP-2/−9) in human NCI-H460 lung and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells.42,43 It produced antimetastatic effects in MDA-MB-231 cells that could be associated with activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway.43 CTD was found to suppress MCF-7 human breast cancer cell adhesion to platelets that protect cancer cells from the host immune system or physical factors, which was mediated through downregulation of the adhesion molecule α2 integrin in the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway.44 Also, CTD inhibited PKB in A549 human lung cancer cells to inhibit MMP-2 selectively, which, in turn, blocked migration and invasion of A549 cells through a phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway.45 Recently, the reversal of metastases in highly metastatic MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells was observed when cells were treated with CTD. This probably resulted from inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) nuclear translocation and the cleavage of the GLUT1/PKM2 glycolytic loop.46 In addition, CTD (1) contributes to the reversal of cancer cell multidrug resistance (MDR). It down-regulated P-glycoprotein (P-gp) expression to reverse MDR observed in human hepatoma HepG2/ADM cells,47 and it also inhibited both imatinib-sensitive and -resistant chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cell growth to overcome the imatinib resistance in these cells.48

Thus far, in vivo investigations that have been reported largely support the antitumor activity of CTD (1). For example, skin tumor formation was inhibited when four–six-week-old male athymic BALB/cnu/nu mice were inoculated with A431 human skin cancer cells, and the tumor volume reached around 200 mm3. Then, mice were treated [intravenously (i.v.), every three days] with CTD (1) (0.2 or 1.0 mg/kg) for two weeks, with no toxic effects observed in the body weights, livers, or spleens of the treated mice.49 The antihepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) efficacy of this monoterpenoid derivative was enhanced by the use of CTD-loaded dual-functional liposomes (DF-Lp/CTD), a novel delivery system prepared by modifying BR2-Lp/CTD with anti-carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX) antibody, when mice were inoculated with HepG2-red-Fluc luciferase-transfected HCC cells (seven days) and treated (tail vein injection, every three days) with CTD (0.4 mg/kg) or DF-Lp/CTD (0.4 mg/kg) for four doses. No obvious toxicity was observed in the test mice used.50 In addition, HCC growth was also delayed significantly when four–six-week-old male BALB/c nude mice were inoculated by human HepG2 HCC cells, and the tumor volume reached around 100 mm3. Mice were then treated orally with CTD (0.1 mg/kg, daily) for two weeks, with no obvious decrease observed in the body weight or splenic index values of the animals tested.51 Also, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) growth was inhibited significantly when four–six-week-old BALB/c nude mice were inoculated by human MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells followed by treatment (i.v.) with CTD (10 mg/kg) every two days for three weeks.52

However, in a recent investigation, CTD (1) was found to accelerate significantly pancreatic tumor xenograft growth when four-week-old female BALB/c athymic nude mice were inoculated with PANC-1 human pancreatic cancer cells followed by treatment [intraperitoneally (i.p.), every three days] with CTD (1.0 mg/kg) for eight doses.53 This unexpected effect could have resulted from the angiogenesis promoted by CTD, as supported by an increased antitumor efficacy observed in the combination treatment of tumor with CTD and other antiangiogenic therapeutics, when compared with the individual treatments. In this in vivo investigation, four-week-old female BALB/c athymic nude mice were inoculated with PANC-1 cells and either treated individually with CTD [i.p., 1.0 mg/kg, every three days], apatinib [10 mg/kg, daily, intragastric (i.g.)], bevacizumab (50 mg/kg, every three days, via the caudal vein), endostar (50 mg/kg, daily, via the caudal vein), ginsenoside Rg3 (20 mg/kg, daily, i.g.), or tamoxifen (0.5 mg/kg, daily, i.g.) for a total of eight doses, or treated with CTD plus apatinib, bevacizumab, endostar, ginsenoside Rg3, or tamoxifen, with the same doses and administration used in the individual treatments. No obvious toxicity was observed in mice in all of these treatments. Thus, CTD could be a promising antivascularization cancer therapeutic agent.53

Mechanistic investigations have shown that CTD (1) targets PP1, PP2A, and PP5 to mediate its antitumor potential,29 and it also inhibits autophagy through suppressing Beclin-1 expression to induce MDA-MB-231 human TNBC cell apoptosis.52 Interestingly, the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor remodeling that is independent of PPs has been characterized recently as an additional molecular target for CTD. GPI is associated with the progression, invasion, and metastasis of malignant cells. Thus, CTD inhibited Cdc1 activity in GPI-anchor remodeling in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to exhibit cytotoxicity against cancer cells.54 In addition, CTD was found to cause oxidative stress to provoke DNA damage and p53-dependent apoptosis,55 and it also targets potentially PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling and promotes autophagy to show antimetastatic and cell proliferation inhibitory effects against A549 human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells.56

In human MGC-803 and BGC-823 gastric cancer (GC) cells, CTD downregulated significantly the expression of colon cancer-associated transcript-1 (CCAT1), also known as cancer-associated region long noncoding RNA 5 (CARLo-5), to inhibit the activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, which may result in inhibition of tumor cell invasion and metastasis.57 CTD was found to bind to and inhibit ephrin type-B receptor 4 (EphB4) to block the downstream Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway and PI3K/Akt signaling, which leads to its antiproliferative activity against HepG2 HCC cells.51 It triggers human osteosarcoma U-2 OS cell apoptosis by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Ca2+ and activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9.58 CTD also induces MNNG/HOS and MG-63 human osteosarcoma cell apoptosis, in which it increases the expression of Bax and PARP and decreases the expression of Bcl-2, p-Akt, and p-Cdc2. This indicated that CTD inhibits the growth of these osteosarcoma cells by activating the mitochondrial pathway.59

Moreover, CTD blocked heat shock factor 1 (HSF1, a protein to enhance the survival of cancer cells under various stresses) and bound to heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) promoter to inhibit Hsp70 and Bcl-2-associated athanogene domain 3 (BAG3) expressions, and it also induced HCT-116 human colorectal cancer cell death in a PP2A-independent manner.60 Heat shock proteins are highly expressed in cancerous cells and promote tumor metastasis formation and resistance to anticancer drugs, and thus Hsps have emerged as promising targets for the discovery of new antineoplastic agents.61,62

In addition, CTD was found to inhibit autophagy in human TNBC cell.52 Autophagy or autophagocytosis, denoting “self eating”, is a non-apoptotic form of cell death and the naturally regulated mechanism of cells, which disassembles unnecessary or dysfunctional components. As an essential protein degradation system of the cell lysosomes, autophagy controls important physiological functions, and the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Dr. Yoshinori Ohsumi for the identification of autophagy-related genes in yeasts (https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2016/press-release). Since mutations in autophagy genes can cause genetic disease, including cancer, autophagy contributes to cancer as both a tumor survival promoter and a tumor suppressor. The early upregulation of autophagy exerts cytoprotective activity, but further upregulation increases autophagic apoptosis. Thus, both induction (enhancing tumor suppression) and inhibition (leading to cell survival and apoptosis) of autophagy may be used as potential anticancer targets.2 In this regard, CTD could be a promising lead, owing to its mediation of a potential antitumor activity by targeting PP, Hsp, and autophagy.

3. Approaches to reducing the toxicity of cantharidin

CTD is one of the major active constituents of the dried body of the Chinese blister beetle (Mylabris phalerata), which has been used as a Chinese traditional medicine to treat cancer for many years.19 However, the clinical use of CTD is limited due to its substantial toxicity. For example, CTD exhibited toxicity to both normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and leukemic stem cells (LSCs), which decreases its promise of use in the treatment of leukemia.40 It is also a skin vesicant and leads to urinary irritation, with the acute median lethal dose (LD50, i.p.) of 1.7 mg/kg in mice being observed.19 A case of fatal poisoning was reported for a 38-year-old person who took a cup of tea laced with three teaspoonsful of powder of cantharides from the blister beetle Cantharis vesicatoria (Lytta vesicatoria or Spanish fly) containing an ingested dose of 26–45 mg of CTD.63 Also, potential CTD poisoning has been observed to be associated with certain patients who have unexplained hematuria.64 Thus, the reduction of toxicity of CTD has become a critical issue for the development of this compound as an anticancer drug.

Previous investigations showed that CTD was less cytoxic toward normal cell lines than Adriamycin (doxorubicin), an anticancer drug used commonly in cancer clinics for the treatment of leukemias, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and other solid tumors (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doxorubicin). The cytotoxicity of CTD against the Chang human normal liver cell line was 13 times less potent than that toward the Hep 3B human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. More importantly, CTD was found to inhibit progression of all phases of the Hep 3B cell cycle, suggesting that this agent may be used with other standard chemotherapeutics to treat cancer effectively.65 Thus, the use of CTD as a possible therapeutic agent has been revisited, with modified formulations and synthetic derivatives being investigated.66

An in vitro investigation demonstrated that cytotoxicity of CTD against human breast cancer MCF-7 cells was found to be reduced drastically when this compound was encapsulated into pegylated liposomes. Further in vivo experiments showed that the liposomal CTD exhibited significantly less systemic toxicity than CTD itself, and the 60-day survival rate of mice injected with these liposomes was increased greatly when four–five-week-old female BALB/cByJNarl mice were treated (i.p.) with CTD or liposomal CTD (5 mg/kg for each) on the first, fifth, and seventh days.67 Also, the breast tumor growth was found to be inhibited significantly by liposomal CTD in the same animal model when the mice were inoculated by human breast cancer MCF-7 cells (11 days) and then treated (i.p.) with CTD or liposomal CTD (5 mg/kg for each) on the first and third days. When the tumor volume was tested on the nineteenth day after the treatment, all of the tumor-bearing mice in the CTD-treatment group died. These in vivo investigations indicate that the pegylated liposomal CTD exhibited antitumor activity while they decreased the mouse toxicity of CTD.67

Following this approach, several new formulations have been developed for the improvement of the antitumor activity of CTD. Of these, liver-targeted and CTD-loaded 3-galactosidase- and 3-succinyl-30-stearyl deoxyglycyrrhetinic acid-modified liposomes (11-DGA-3-O-Gal-CTD-lip and 18-GA-Suc-CTD-Lip) were found to show more potent cytotoxicity toward HepG2 HCC cells and increased the cell migration inhibition, when compared with CTD liposomes.68,69 A cancer cell membrane-camouflaged nanocarrier was developed and loaded with tellurium (Te) and CTD (m-CTD@Te), using 4T1 murine breast cancer cell membrane. These nanoparticles showed synergistic effects on the cancer cells, of which CTD was used as the heat shock response (HSR) inhibitor, Te functioned as the photothermal and photodynamic therapy photosensitizer, and 4T1 cells exhibited tumor targeting ability. Thus, the cytotoxicity of CTD toward 4T1 cells was enhanced greatly by m-CTD@Te.70 In addition, a preparation of CTD-loaded titanium peroxide nanoparticles with YSA peptide, namely, YSA-PEG-TiOX/CTD, improved the cytotoxicity of CTD against ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EphA2) overexpressing A549 NSCLC cells, which was further potentiated by the TiOx generated adequate ROS under X-ray irradiation. Thus, YSA-PEG-TiOX nanoparticles were suggested as a promising formulation for the effective treatment of NSCLC.71

An in vivo study showed that a combination treatment with the cell membrane-coated m-CTD@Te nanoparticles and laser irradiation inhibited tumor growth significantly when six-week-old female BALB/c mice were inoculated by 4T1 murine breast cancer cells, and the tumor volume reached around 50 mm3. Then, mice were treated (i.v., single dose) with m-CTD@Te (0.1 mg/kg CTD) plus laser irradiation (NIR laser for 10 min 24 h post-administration) at the tumor area, and the tumor volume was measured on the sixteenth day. No adverse effects were observed on the normal tissues of mice tested, demonstrating that the m-CTD@Te could target tumors selectively to suppress tumor growth.70 In another in vivo study, the toxicity of CTD was found to be decreased by use of a CA IX-based DF-Lp/CTD delivery system, of which CA IX is a cell surface enzyme over-expressed in many solid tumors vis-à-vis their corresponding normal tissues.50

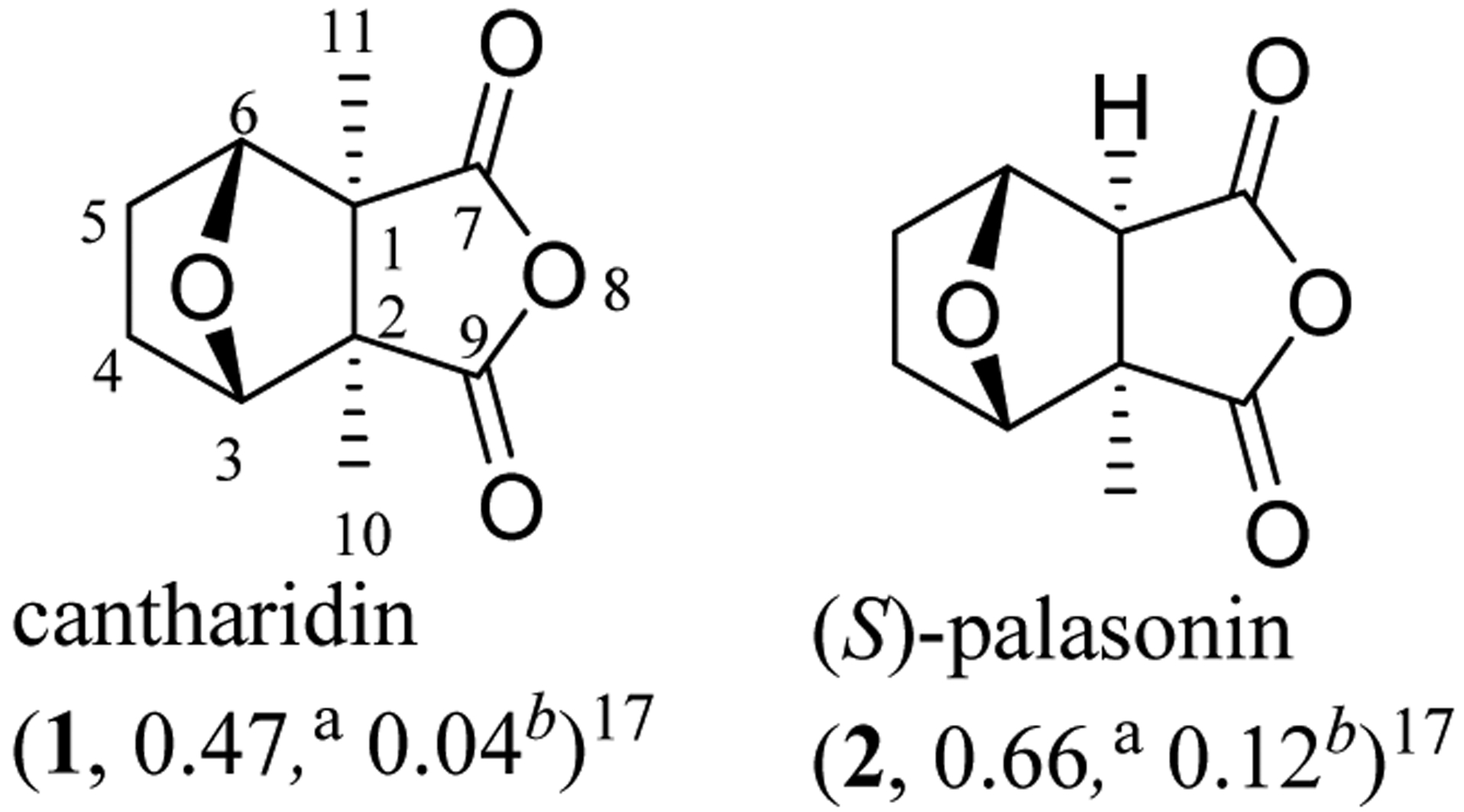

In addition, several semi-synthetic derivatives of CTD were found to be less toxic than the parent compound, including norcantharidin (NCTD, 3), cantharidic acid (4), and endothall (5) (Table 1, Figure 2).17,19,72 Of these, NCTD (3) (median lethal dose LD50 4.0 mg/kg) showed lower mouse intraperitoneal toxicity than CTD (LD50 1.0 mg/kg) (Table 1) and exhibited potential antitumor activity, including induction of cancer cell apoptosis, inhibition of cancer cell adhesion and metastasis and tumor vessel generation, and the elevation of leukocyte levels.17,73,74

Fig. 2.

Structures of cantharidin derivatives (3–10) and IC50 values (μM) toward the human aHepG2 hepatoma and cSMMC-7721 and dBel-7402 HCC cell lines and for the binhibition of PP2A.

When tested against the NCI60 cell line panel, NCTD showed overall less potent activity than CTD, and both compounds exhibited different cytotoxicity profiles. Intriguingly, NCTD was found to mediate its activity against HepG2 human HCC cells through a mechanism different from that proposed for CTD, indicating that the C-10 and C-11 methyl groups of CTD could play important roles in the interaction between this compound and its molecular targets.75 In vitro studies showed that the proliferation and invasion of GBC-SD human gallbladder cancer cells were suppressed when cells were treated by NCTD, and NCTD enhanced the killing effect of cisplatin on bladder cancer stem cell-like cells.76,77 While NCTD induced apoptosis in 22Rv1 and Du145 human prostate cancer cells,78 it reduced the mitochondrial membrane potential and induced mitophagy followed by subsequent cellular autophagy and apoptosis in SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells, which resulted in the inhibition of cancer cell growth.79 In addition, NCTD upregulated family with sequence similarity 46 member C (FAM46C), a tumor suppressor for multiple myeloma, to inhibit HCC cell growth,80 and suppressed the migration and invasion and colony-formation of osteosarcoma cells, which involved autophagy, mitophagy, ER stress, and the c-Met pathways.81 Also, NCTD was found to block vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)/MEK/ERK signaling to inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced cell proliferation, migration, invasion,82 and it inhibited Wnt-β-catenin signaling to prohibit human DAOY medulloblastoma cell growth.83

Aberrant activation of β-catenin signaling contributes to the maintenance of cancer stem cells (CSCs) that sustain tumor formation and growth and has been hypothesized to account for certain forms of cancer chemotherapeutic agent resistance. NCTD prevented the stemness of pancreatic cancer cells in a β-catenin pathway-dependent manner, and thus it was found to enhance the cytotoxicity of gemcitabine and erlotinib.84 A recent mechanistic investigation indicated that autophagy suppression enhanced the pro-apoptotic action of NCTD in its induction of QBC939 CCA cell death, which may involve activation of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).85

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) have an enhanced DNA damage response (DDR) and thus are resistant to DNA-damaging-agents. The expression of chromatin-binding cdc6 that assemble a pre-replication complex to initiate DNA replication is increased in bladder CSCs (BCSCs), in which DDR activity was reduced by NCTD through cdc6 degradation and inhibition of activation of the ATR-Chk1 pathway. Thus, NCTD was found to increase the treatment outcomes of cisplatin (CDDP or DDP, cis-diaminodichloroplatinum) in BCSCs.77 Recently, NCTD was found to suppress the focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/paxillin, which leads to inhibition of the migration and invasion of YD-15 human tongue mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells.86 FAM46C is a non-canonical poly(A) polymerase, of which the expression induces apoptosis and inhibits glycolysis of colorectal cancer cells. Similarly, NCTD inhibited HT-29 human colon cancer cell proliferation and glycolysis, which might be mediated by targeting FAM46C and inhibiting ERK1/2 signaling.87 However, both cytotoxicity toward human cancer cells and inhibition of PP1 and PP2A by NCTD were found to be less potent than those of CTD (1) (Tables 1 and 2), and thus extensive structure-activity relationship (SAR) investigations have been completed on CTD and NCTD to improve their potential antitumor activities.88

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity of compounds 1, 3, 4, and 8–10.

| compound | HT-29a | HCT116b | HepG2c | HL-60d | KB-3-1e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cantharidin (1)93,94 | 6.493 | 9.093 | 19.194 | 2.794 | 2.794 |

| norcantharidin (3)93,94 | 3393 | 2493 | 212.994 | 15.794 | 69.594 |

| cantharidic acid (4)94 | 218.5 | 103.2 | 79.2 | ||

| 9-deoxocantharidin (8)94 | >200 | >200 | >200 | ||

| 9-deoxonorcantharidin (9)94 | >200 | >200 | 112.0 | ||

| cis-5-norbornene-endo-2,3-dicarboxylic anhydride (10)95 | 62 |

IC50 values (μM) toward the human aHT-29 and bHCT116 colon cancer, cHepG2 hepatoma, dHL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia, eKB-3–1 oral cancer cell lines.

A monosodium salt of NCTD, namely, sodium demethylcantharidate (6, Na-NCTD), was found to induce apoptosis and to show moderate cytotoxicity against SMMC-7721 and Bel-7402 human HCC cells, with IC50 values being in the range 12.5–25 μM (Figure 2). Liver tumor growth was inhibited when four-week-old male BALB/c nude mice were inoculated by SMMC-7721 cells (a week) and treated (i.p., every other day) with sodium demethylcantharidate (4.3 mg/kg) for 16 days.89 Western blotting showed that ER stress-related proteins, including p-IRE1, GRP78/BiP, CHOP, XBP1, and caspase-12, were all upregulated in both SMMC-7721 and Bel-7402 cells treated by 6, indicating that Na-NCTD induces apoptosis via ER stress.89 Consistently, a disodium salt, disodium demethylcantharidate (7, Na2-NCTD), showed cytotoxicity against a small panel of cancer cell lines, with IC50 values being in the range 15–62 μM. Intriguingly, a new polymeric didemethylcantharidato-bridged Cu(II) phenanthroline complex was more potently cytotoxic than Na2-NCTD against this same panel of cells, with IC50 values observed in the 0.5–4 μM range.90 However, on replacement of one or two of the Na+ ions by K+, Mg2+, or Ba2+ ions, the activity toward cancer cells did not change greatly, indicating that the type of salt present in the modified NCTD molecule did not affect the cytotoxic potency appreciably.91

Furthermore, a series of the dicarboxylic acid analogues was prepared, and all of these derivatives were found to be less potently acutely toxic for mice (i.p.) than their anhydride analogues,92 as represented in order by cantharidin (1, 1.0 mg/kg), cantharidic acid (4, 1.8 mg/kg), norcantharidin (3, 4.0 mg/kg), and endothall (5, 14.0 mg/kg) (Table 1). However, these derivatives showed less potent activities than their parent compounds against cancer cells and PP inhibition.93 On changing the anhydride functionality to a lactone unit [e.g., (9-deoxocantharidin (8) and 9-deoxonorcantharidin (9)], both activities were abolished (IC50 >50 μM) (Tables 1 and 2).94 Also, replacing the bridge ether oxygen with a methylene group and introducing a double bond at the C-4 and C-5 positions [e.g., cis-5-norbornene-endo-2,3-dicarboxylic anhydride (10)] decreased slightly the cytotoxicity of NCTD against HepG2 human hepatoma cells but abrogated activity toward normal rat hepatocytes.95 In addition, cantharidic acid (4) was found recently to induce apoptosis of human leukemic HL-60 cells via the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-regulated caspase-8/−9/−3 activation pathway.96 These results indicate that the synthetic modification of CTD may potentiate its antitumor activity.

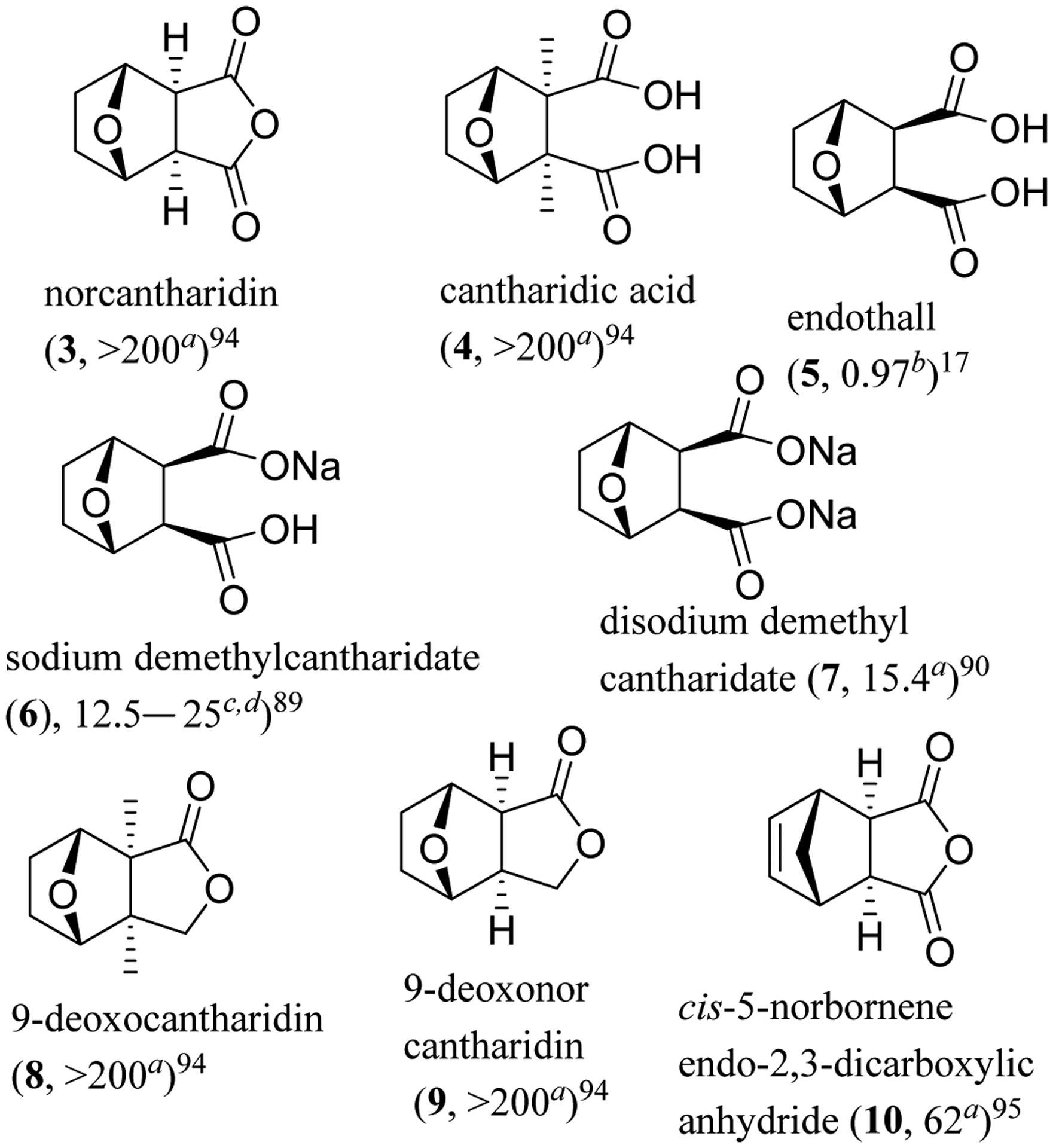

Following this indication, N-methylcantharidinimide (11) that was less toxic than CTD but non-cytotoxic toward Hep3B and SK-Hep-1 human hepatoma cells was modified synthetically.19,97 Several N-thiazolyl and N-thiadiazolylcantharidinimides were prepared and evaluated for their cytotoxicity against these cancer cells, of which N-[2-(5-nitrothiazolyl)]cantharidinimide (12) was found to be active, with IC50 values of 0.4 and 1.25 μM, respectively (Figure 3).97 Further modification of 12 resulted in the production of CAN 032 (13), which showed cytotoxicity against Hep3B and SK-Hep-1 HCC cells, with the potency being comparable with that of CTD. Importantly, in being different from CTD, which showed cytotoxicity toward three non-malignant BM1, BM2, and BM3 human hematological bone marrow cell lines (IC50 values in the range 6.5–12.5 μg/mL), CAN 032 did not show any activity against these normal bone marrow cells (IC50 >12.5 μg/mL).98 CAN 032 also inhibited the growth of KG1a acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and K562 chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells through a caspase-dependent pathway.99 Following this, the most highly cytotoxic NCTD analogues to date were prepared from the synthesis of octahydroepoxyisoindole-7-carboxylic acid and norcantharidin-amide hybrids, of which compound 14 (Figure 3) showed potent cytotoxicity against the HT-29 colon (IC50 15 nM), MCF-7 breast (IC50 27 nM), A431 epidermoid (IC50 45 nM), DU145 prostate (IC50 26 nM), BE2-C neuroblastic (IC50 29 nM), and MIA pancreatic (IC50 56 nM) human cancer cell lines.100

Fig. 3.

Structures of cantharimide derivatives (11–14) and IC50 values toward human aHep3B hepatoma and bHT-29 colon cancer cells.

4. Development of anticancer drug conjugates of cantharidin

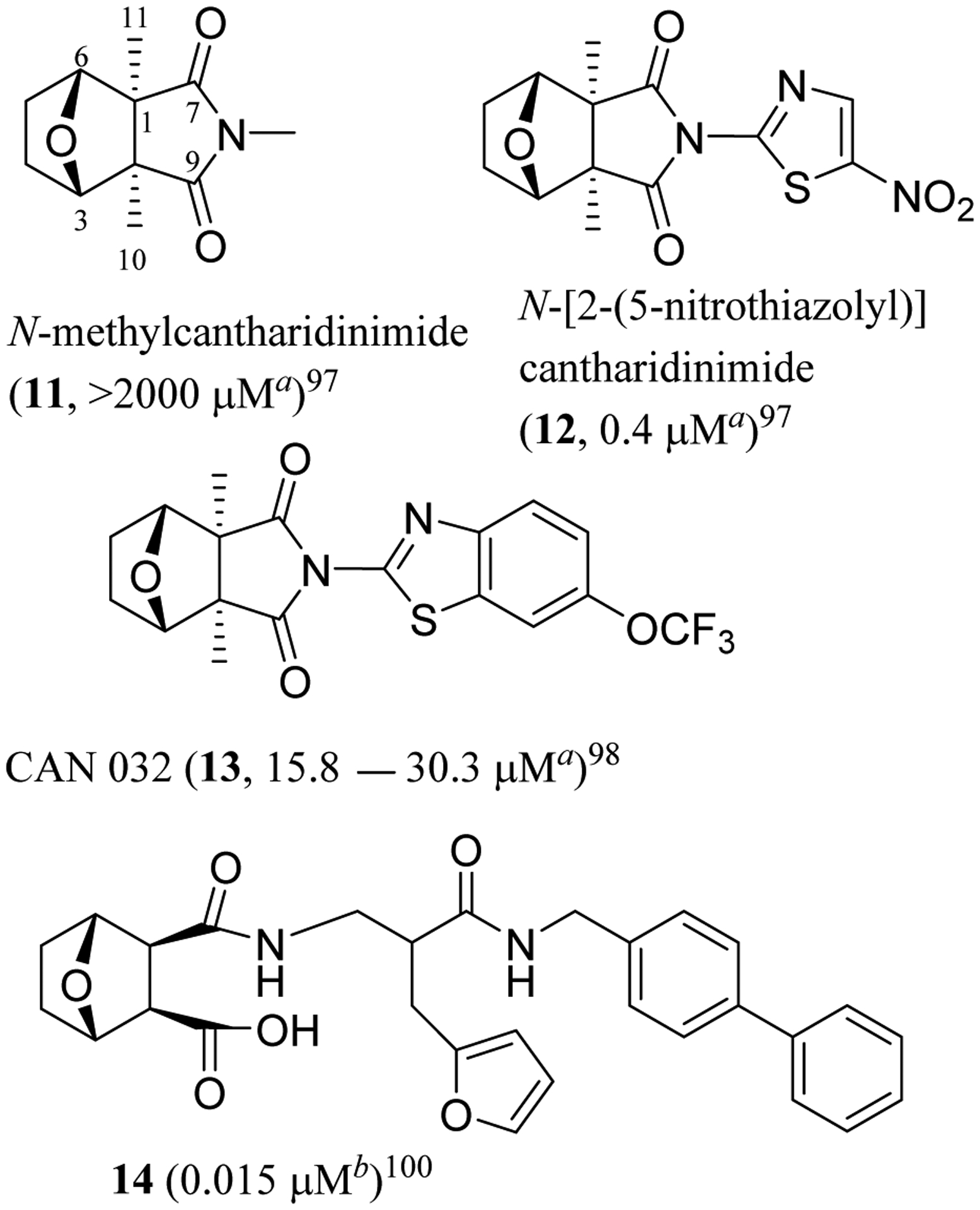

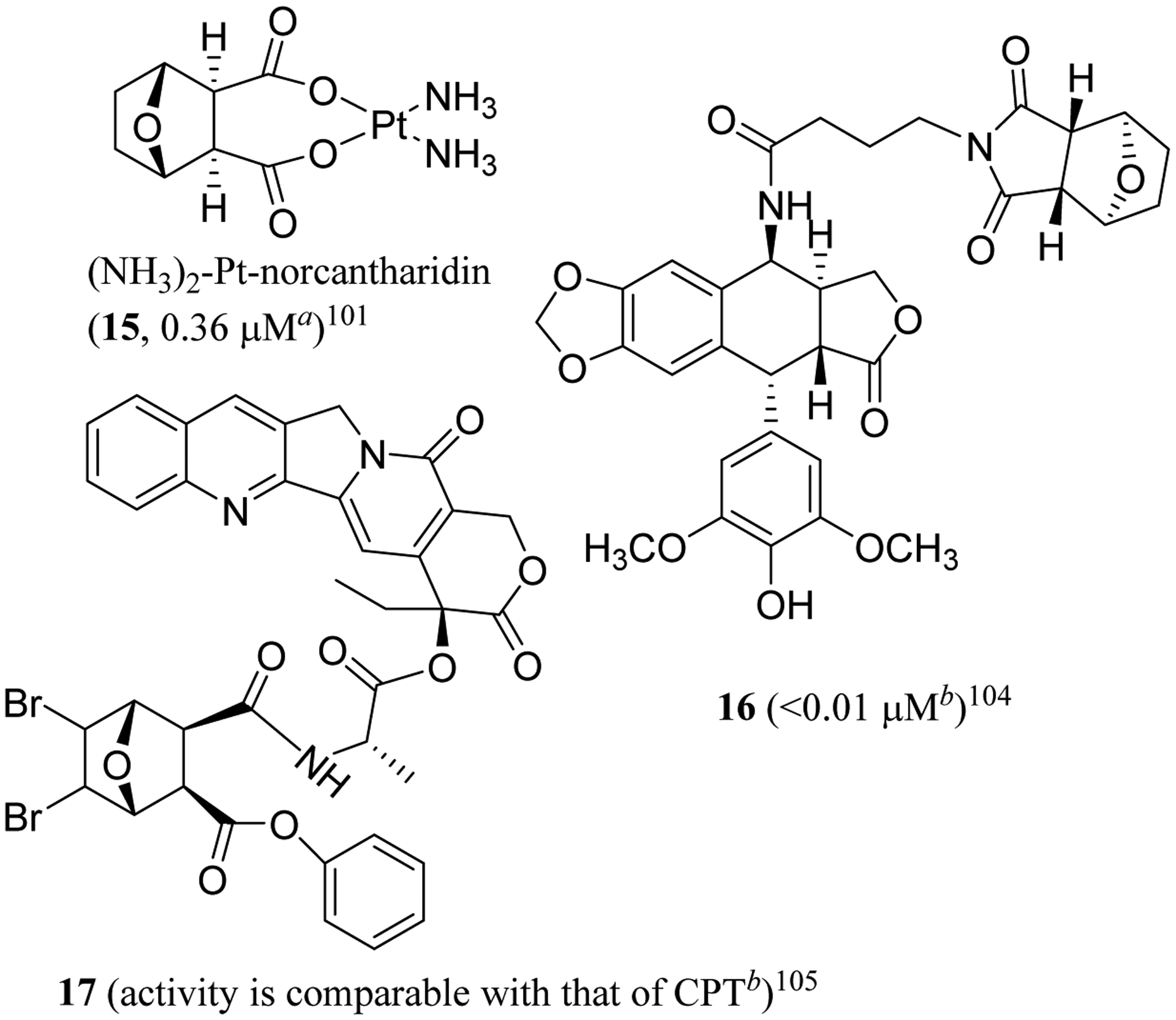

Additional progress has been made on the development of CTD derivatives through an innovative complexation process. A series of NCTD-based platinum (Pt) analogues, including (NH3)2-Pt-norcantharidin (15) (Figure 4), were prepared from the incorporation of a Pt atom into NCTD. These Pt-containing NCTD derivatives exhibited cytotoxicity toward a small panel of human cancer cells, with the potency being comparable to that of cisplatin.101 In addition, these novel complexes inhibited PP1 and PP2A and were cytotoxic against cisplatin-resistant L1210 mouse leukemia and NCI H460 human non-small cell lung cancer cells,102 with DNA damage being observed in HCT116 colorectal cancer cells treated with 15.103

Fig. 4.

Structures of norcantharidin drug conjugates (15–17) and IC50 values toward human aNTERA-Scl-D1 testicular cancer and bHepG2 hepatoma cells.

Significantly, these novel derivatives showed more potent in vivo antitumor efficacy than cisplatin when athymic male nude mice were inoculated by SK-Hep-1 cells and treated (i.p.) with Pt-NCTD complexes (25 mg/kg, once four days) for 60 days, with considerably less toxicity than cisplatin being observed in mice.101 The potential dual mechanism of action targeting inhibition of PP2A and Pt platination of DNA, the lack of cross-resistance, the higher potency, and lower toxicity make these novel demethylcantharidin-integrated platinum anticancer complexes promising as potentially effective antitumor agents.101

Following this development, several novel conjugates were synthesized by coupling 4’-demethylepipodophyllotoxin with N-amino acid norcantharimides, and their cytotoxic effects were evaluated against a small panel of human tumor and a normal WI-38 human diploid fibroblast cell lines. Most of these synthetic products showed more selective potent cytotoxicity than their parent compounds, etoposide (VP-16), or NCTD. Of these, compound 16 was the most potent against HepG2 human hepatoma cells (IC50 <0.01 μM), but it was non-cytotoxic toward WI-38 cells (IC50 >100 μM). This conjugate (16) inhibited topoisomerase (topo II) and PP2A and induced cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase, indicating the possibility of the development of 16 as anticancer agent with a topo II/PP2A dual mechanism.104 Similarly, conjugates of camptothecin (CPT) and norcantharidin (17) linked by alanine were found to suppress cancer cell growth through the inhibition of topo I and CDC 25 B protein phosphatase simultaneously, with the cytotoxic potency being comparable to that of camptothecin (Figure 4). This indicates that NCTD could be a valuable bifunctional target drug candidate for the development of novel cancer chemotherapy.105

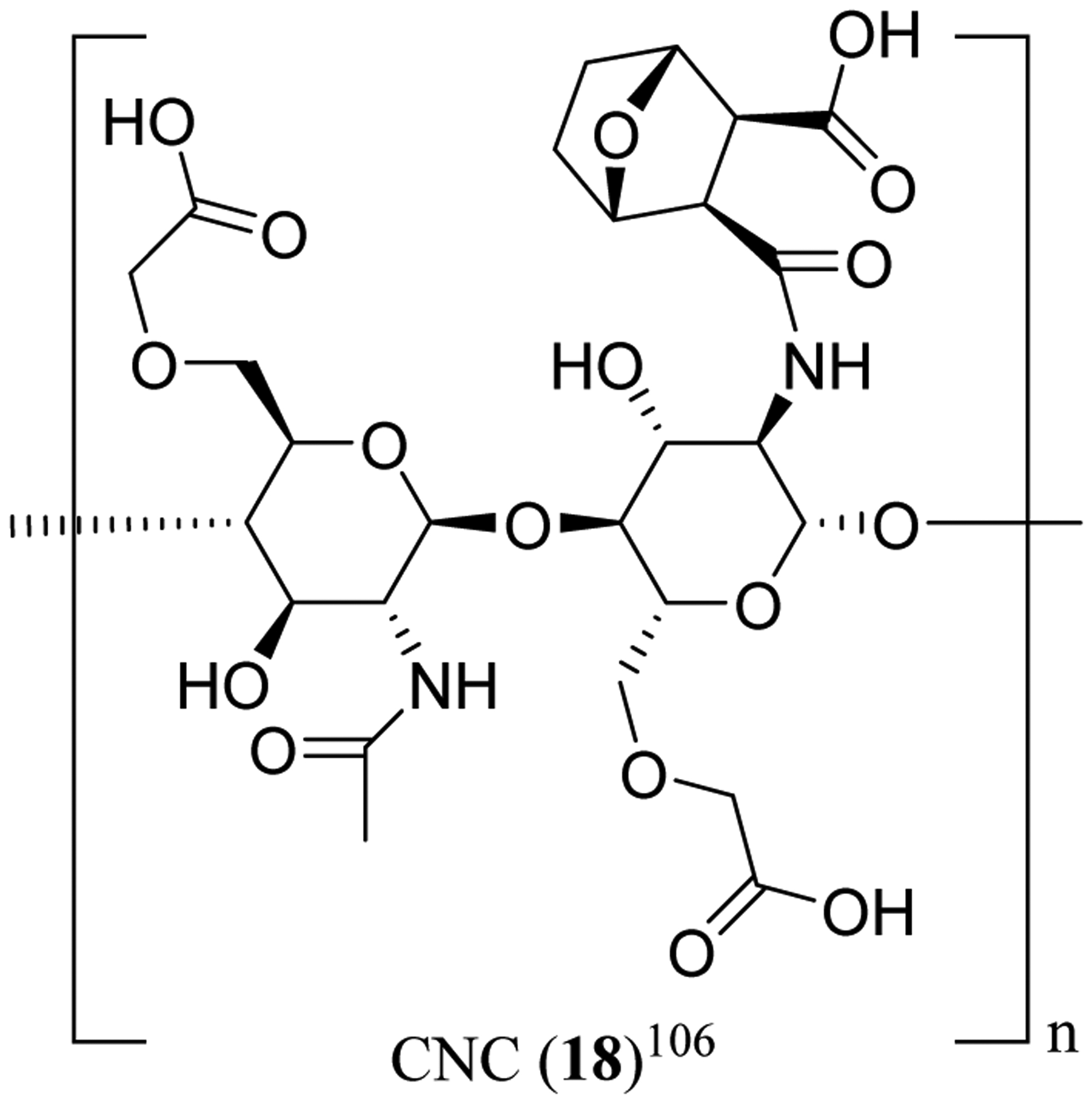

Furthermore, a series of novel polymeric drug conjugates (CNC, 18) (Figure 5) was prepared from carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS) and norcantharidin (NCTD). These CNC conjugates inhibited significantly the proliferation of SGC-7901 human gastric cancer cells and suppressed the migration and tube formation of HUVECs, and they were more effective than NCTD in triggering SGC-7901 cell apoptosis. CNC enhanced antitumor efficacy of NCTD and reduced the toxicity of this parent compound when female BALB/c nude mice were inoculated by SGC-7901 cells followed by treatment (tail vein injection) with NCTD (6.524 mg/kg) or CNC (16.31 or 32.62 mg/kg) every other day for 24 days.106 Mechanistically, CNC were found to upregulate the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and Bax and to downregulate the expression of VEGF, Bcl-2, MMP-2 and MMP-9, and they also induced apoptosis and inhibited tumor metastasis. Thus, these CNC conjugates seem worthy of further investigation for the treatment of gastrointestinal tumors.106

Fig. 5.

Structures of the norcantharidin drug conjugate CNC (18).

5. Concluding remarks

The signaling pathways for cancer cells and stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) to communicate involve dysregulation of protein phosphatases, which are thus essential in order for the TME to undergo cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy.16 In addition, protein phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) is encoded by the PTEN gene, for which mutations are required for the development of cancers. PTEN deficiency is linked to tumor promotion by the dysregulation of PI3K/Akt and DNA damage and contributes to immunosuppression of the TME.107 Ppp2r2d, a regulatory subunit of the PP2A phosphatase family, directs PP2A to Cdk1 substrates to inhibit entry into mitosis and to induce exit from mitosis. The Ppp2r2d shRNA induces accumulation of OT-I CD8 T cells and CD4 T cells and enhances antitumor responses when introduced into T cells, which are able to specifically detect and eliminate cancer cells and hence play a critical role in immune-mediated control of cancer. Thus, Ppp2r2d has been identified as a target gene for immunotherapy in the complex TME.108

Several classes of CSC-targeted drugs have been developed, including stem cell-targeting, stemness inhibitory, and stemness-promoting drugs, with the TME-modulating drugs that target selectively CSC niche being investigated. However, the complex cellular heterogeneity of cancers limits the clinical use of these drugs, and better understanding of CSC biology and of the TME could be helpful for the development of more effective cancer treatment regimens.109

Cantharidin (CTD) was isolated for the first time in 1810 from the green Spanish fly, Lytta vesicatoria (L.) [Cantharis vesicatoria (Canth.)] (Meloidae), by the French chemist, Pierre Robiquet (https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol17/iss4/1.), and it is secreted by many species of blister beetle.110,111 The proposed structure of CTD was confirmed by total synthesis of cis-1,2-dimethylcyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylic anhydride in 1941, and the complete molecular structure with the (1S,2R,3S,4R) absolute configuration of cantharidin has been established by analysis of its single-crystal X-ray diffraction data, inclusive of a value of 1(3) defined from the Flack parameter for CTD.112–114

CTD exhibits both potent PP2A inhibitory activity (IC50 0.04 μM) and promising antitumor activity,17,18 and several new CTD derivatives and formulations with improved antitumor potential have been developed. As shown in Table 3, the activity against liver cancer cells of CTD and its derivatives has been investigated extensively, indicating that CTD may be developed as a novel agent to treat lethal liver cancer. Of these, a topo I and PP2A dual-targeted CPT-alanine-NCTD (17) conjugate was found to show a comparable cytotoxicity against HCC with CPT.105 Importantly, CTD itself and several of its derivatives modulate their antitumor activity by targeting either the TME components, including CSCs, angiogenic and metabolic molecules, and HIF-1α, or the TME-related signaling pathways, including IGF-1/IGF-1R, Notch, PD-L1, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, VEGFR2/MEK/ERK, and Wnt2. Thus, it could be promising to develop CTD as a TME-targeted liver cancer chemotherapeutic agent or some novel dual-targeted cancer drug conjugates.

Table 3.

Potential antitumor activity of cantharidin and its analogues or derivatives.

| compound | antitumor potential | refs. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | colon, liver, lung, and oral cancer and leukemia cells (IC50 2–20 μM), targeting mainly p53, PP, and PI3K/Akt | 17,51,55,56,60,93,94 |

| 2 | PP inhibitory (IC50 <1 μM) | 17 |

| 3 | colon, liver, and oral cancer and leukemia cells (IC50 >15 μM), targeting mainly PP, ROS, and VEGF | 17,82,83,85,93,94 |

| 4 | liver and oral cancer and leukemia cells (IC50 >50 μM), targeting mainly PP | 17,94 |

| 5 | PP inhibitory (IC50 >0.9 μM) | 17 |

| 6 | liver cancer cells (IC50 12–25 μM), targeting mainly ER | 89 |

| 7 | liver cancer cells (IC50 around 15 μM) | 90 |

| 8 | inactive | 94 |

| 9 | inactive | 94 |

| 10 | liver cancer cells (IC50 around 60 μM) | 95 |

| 11 | inactive | 97 |

| 12 | liver cancer cells (IC50 <1 μM) | 97 |

| 13 | liver cancer cells (IC50 6.5–12.5 μM) | 98 |

| 14 | colon cancer cells (IC50 0.015 μM) | 100 |

| 15 | testicular cancer cells (IC50 0.36 μM), targeting mainly PP and DNA damage | 101–103 |

| 16 | liver cancer cells (IC50 <0.01 μM), targeting mainly PP and topo II | 104 |

| 17 | liver cancer cells (similar with CPT), targeting mainly PP and topo I | 105 |

| 18 | gastric cancer cells (more potent than 3), targeting mainly Bcl-2, MMP, and VEGF | 106 |

Moreover, CTD exhibits potential PP-mediated antitumor properties and the ability to increase the number of leucocytes, which is highly desired clinically,19 and SAR investigations suggest the importance of the anhydride unit in the mediation of its antitumor activity. For example, changing the anhydride moiety to a 1,2-dicarboxylic acid unit results in the acute toxicity, cancer cell cytotoxicity, and PP2A inhibitory potency of CTD all being weakened, and these activities are abolished if the anhydride group is altered to a lactone unit.92–94 Also, several drug conjugates of NCTD were found to exhibit an improved antitumor potency, including NCTD-cisplatin, NCTD-CPT, and NCTD-4’-demethylepipodophyllotoxin.101,104,105 Following these observations, more interesting agents may be produced from further modifications at the anhydride unit of CTD, and some of these compounds may better contribute to cancer treatment by improving their stimulatory effects on leucocytes.

A mono-demethylated analogue of CTD, (S)-palasonin (2), was isolated from both the seeds of plant Butea frondosa and a beetle species, Trichodes apiarius,20–22 indicating that some novel PP inhibitory analogues of CTD may be produced by both plants and insects. Accordingly, a continued search for CTD analogues from other natural sources, introducing an anhydride unit to an existing lead compound, or alteration of a lactone unit that exists in many active natural products to an anhydride moiety, could all be supportive of the discovery of further novel protein phosphatase inhibitors to contribute to the control of cancer.

Thus far, many effective drugs for the treatment of a variety of human diseases have been discovered and developed from natural products,115 and natural sources, including tropical plants, aquatic and terrestrial cyanobacteria, and filamentous fungi, have been proved to be valuable for the discovery of promising anticancer agents.116,117 Thus, the specific search for novel natural product protein phosphatase inhibitors, along with their further structural modification by chemical synthesis, could represent a reasonable strategy for the improvement of the TME-targeted cancer chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

The completion of this review article was supported by program project P01 CA125066 funded by the National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA. We thank Dr. David J. Hart, Emeritus Professor, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The Ohio State University, for many helpful comments about the structure and synthetic modifications of cantharidin (CTD).

Abbreviations

- Akt or PKB

protein kinase B

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- AMPK

5’ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- BAG3

Bcl-2-associated athanogene domain 3

- CAF

cancer-associated fibroblast

- CA IX

carbonic anhydrase IX

- CCA

cholangiocarcinoma

- CCAT1

colon cancer-associated transcript-1

- CDDP or DDP

cis-diaminodichloroplatinum (cisplatin)

- CML

chronic myeloid leukemia

- CPT

camptothecin

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CSC

cancer stem cells

- CTD

cantharidin

- EphA2

ephrin type-A receptor 2

- EphB4

ephrin type-B receptor 4

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- GC

gastric cancer

- GLUT

glucose transporter

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HIF

hypoxia inducible factor

- HLF

hepatic leukemia factor

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cells

- HSF1

heat shock factor 1

- Hsp70

heat shock protein 70

- HSR

heat shock response

- IC50

the concentration required for 50% inhibition of cell viability

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor

- i.p.

intraperitoneally

- i.v.

intravenously

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LSC

leukemic stem cell

- LD50

median lethal dose, the dose required to kill half the members of a tested population

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinases

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NCTD

norcantharidin

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- PARP1

poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase 1

- PD-L1/PD-1

programmed death-ligand-1/programmed death-1

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKM2

pyruvate kinase M2

- PP

serine/threonine protein phosphatase

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatases

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- STAT3

signal transducers and activators of transcription 3

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- Wnt

Wingless-related integration site

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Balkwill FR; Capasso M; Hagemann T The tumor microenvironment at a glance. J. Cell Sci 2012, 125, 5591–5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D; Weinberg RA Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boedtkjer E; Pedersen SF The acidic tumor microenvironment as a driver of cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol 2020, 82, 103–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anari F; Ramamurthy C; Zibelman M Impact of tumor microenvironment composition on therapeutic responses and clinical outcomes in cancer. Future Oncol. 2018, 14, 1409–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakagawa S; Miki Y; Miyashita M; Hata S; Takahashi Y; Rai Y; Sagara Y; Ohi Y; Hirakawa H; Tamaki K; Ishida T; Watanabe M; Suzuki T; Ohuchi N; Sasano H Tumor microenvironment in invasive lobular carcinoma: Possible therapeutic targets. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 2016, 155, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aizawa T; Karasawa H; Funayama R; Shirota M; Suzuki T; Maeda S; Suzuki H; Yamamura A; Naitoh T; Nakayama K; Unno M Cancer-associated fibroblasts secrete Wnt2 to promote cancer progression in colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 6370–6382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu T; Han C; Wang S; Fang P; Ma Z; Xu L; Yin R Cancer-associated fibroblasts: An emerging target of anticancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol 2019, 12, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng W; Liu P; Pan W; Singh SR; Wei Y Hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factors in tumor metabolism. Cancer Lett. 2015, 356, 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li F; Simon MC Cancer cells don’t live alone: Metabolic communication within tumor microenvironments. Devel. Cell 2020, 54, 183–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kise K; Kinugasa-Katayama Y; Takakura N Tumor microenvironment for cancer stem cells. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2016, 99, 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khosravi N; Mokhtarzadeh A; Baghbanzadeh A; Hajiasgharzadeh K; Shahgoli VK; Hemmat N; Safarzadeh E; Baradaran B Immune checkpoints in tumor microenvironment and their relevance to the development of cancer stem cells. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 118005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schito L Bridging angiogenesis and immune evasion in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 2018, 315, R1072–R1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun Y Tumor microenvironment and cancer therapy resistance. Cancer Lett. 2016, 380, 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khandani NK; Ghahremanloo A; Hashemy SI Role of tumor microenvironment in the regulation of PD-L1: A novel role in resistance to cancer immunotherapy. J. Cell. Physiol 2020, 235, 6496–6506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendriks WJAJ; Elson A; Harroch S; Pulido R; Stoker A; den Hertog J Protein tyrosine phosphatases in health and disease. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 708–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruvolo PP Role of protein phosphatases in the cancer microenvironment. BBA Mol. Cell Res 2019, 1866, 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y-M; Mackintosh C; Casida JE Protein phosphatase 2A and its [3H]cantharidin/[3H]endothall thioanhydride binding site. Inhibitor specificity of cantharidin and ATP analogues. Biochem. Pharmacol 1993, 46, 1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng LP; Dong J; Cai H; Wang W Cantharidin as an antitumor agent: A retrospective review. Curr. Med. Chem 2013, 20, 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang G-S Medical uses of mylabris in ancient China and recent studies. J. Ethnopharmacol 1989, 26, 147–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raj RK; Kurup PA Isolation & characterization of palasonin, an anthelmintic principle of the seeds of Butea frondosa. Indian J. Chem 1967, 5, 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bochis RJ; Fisher MH The structure of palasonin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968, 1971–1974. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fietz O; Dettner K; Görls H; Klemm K; Boland W (R)-(+)-Palasonin, a cantharidin-related plant toxin, also occurs in insect hemolymph and tissues. J. Chem. Ecol 2002, 28, 1315–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dauben WG; Lam JYL; Guo ZR Total synthesis of (–)-palasonin and (+)-palasonin and related chemistry. J. Org. Chem 1996, 61, 4816–4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chun J; Park MK; Ko H; Lee K; Kim YS Bioassay-guided isolation of cantharidin from blister beetles and its anticancer activity through inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated STAT3 and Akt pathways. J. Nat. Med 2018, 72, 937–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng Y-B; Liu X-L; Zhang Y; Li C-J; Zhang D-M; Peng Y-Z; Zhou X; Du H-F; Tan C-B; Zhang Y-Y; Yang D-J Cantharimide and its derivatives from the blister beetle Mylabris phalerata Palla. J. Nat. Prod 2016, 79, 2032–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng Y-Y; Zhang W; Lei X-P; Zhang D-M; He J; Wang L; Ye W-C Four new cantharidin derivatives from the Chinese blister beetles, Mylabris phalerata. Heterocycles 2017, 94, 1573–1581. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng Y-Y; Zhang W; Li N-P; Lei X-P; Gong X-Y; Zhang D-M; Wang L; Ye W-C Cantharidin derivatives from the medicinal insect Mylabris phalerata. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 5932–5939. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang G; Chengkai; Wang W; Wu C; Hu C; Deng L The new developments of cantharidin and its analogues. J. Chem. Soc. Pak 2017, 39, 599–609. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang G; Dong J; Deng L Overview of cantharidin and its analogues. Curr. Med. Chem 2018, 25, 2034–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dutta P; Sahu RK; Dey T; Lahkar MD; Manna P; Kalita J Beneficial role of insect-derived bioactive components against inflammation and its associated complications (colitis and arthritis) and cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact 2019, 313, 108824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y-M; Casida JE Cantharidin-binding protein: Identification as protein phosphatase 2A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 11867–11870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou H; Xu J; Wang S; Peng J Role of cantharidin in the activation of IKKα/IκBa/NF-κB pathway by inhibiting PP2A activity in cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. Mol. Med. Rep 2018, 17, 7672–7682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCluskey A; Ackland SP; Gardiner E; Walkom CC; Sakoff JA The inhibition of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A: A new target for rational anticancer drug design? Anticancer Drug Des. 2001, 16, 291–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakoff JA; Ackland SP; Baldwin ML; Keane MA; McCluskey A Anticancer activity and protein phosphatase 1 and 2A inhibition of a new generation of cantharidin analogues. Invest. New Drugs 2002, 20, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonness K; Aragon IV; Rutland B; Ofori-Acquah S; Dean NM; Honkanen RE Cantharidin-induced mitotic arrest is associated with the formation of aberrant mitotic spindles and lagging chromosomes resulting, in part, from the suppression of PP2Aα. Mol. Cancer Ther 2006, 5, 2727–2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baba Y; Hirukawa N; Sodeoka M Optically active cantharidin analogues possessing selective inhibitory activity on Ser/Thr protein phosphatase 2B (calcineurin): Implications for the binding mode. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2005, 13, 5164–5170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertini I; Calderone V; Fragai M; Luchinat C; Talluri E Structural basis of serine/threonine phosphatase inhibition by the archetypal small molecules cantharidin and norcantharidin. J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 4838–4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu M-H; Huang T-T; Chao T-I; Chen L-J; Chen Y-L; Tsai M-H; Liu C-Y; Kao J-H; Chen K-F Serine/threonine protein phosphatase 5 is a potential therapeutic target in cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 2248–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qiao Z; Kondo T Identification of cantharidin as a drug candidate for glioblastoma by using a Connectivity Map-based approach. J. Electrophor 2019, 63, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dorn DC; Kou CA; Png KJ; Moore MAS The effect of cantharidins on leukemic stem cells. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 124, 2186–2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mu Z; Sun Q Cantharidin inhibits melanoma cell proliferation via the miR-21-mediated PTEN pathway. Mol. Med. Rep 2018, 18, 4603–4610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsia T-C; Yu C-C; Hsiao Y-T; Wu S-H; Bau D-T; Lu H-F; Huang Y-P; Lin J-G; Chang S-J; Chung J-G Cantharidin impairs cell migration and invasion of human lung cancer NCI-H460 cells via UPA and MAPK signaling pathways. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 5989–5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gu X-D; Xu L-L; Zhao H; Gu J-Z; Xie X-H Cantharidin suppressed breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell growth and migration by inhibiting MAPK signaling pathway. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res 2017, 50, e5920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shou L-M; Zhang Q-Y; Li W; Xie X; Chen K; Lian L; Li Z-Y; Gong F-R; Dai K-S; Mao Y-X; Tao M Cantharidin and norcantharidin inhibit the ability of MCF-7 cells to adhere to platelets via protein kinase C pathway-dependent downregulation of α2 integrin. Oncol. Rep 2013, 30, 1059–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim YM; Ku MJ; Son Y-J; Yun J-M; Kim SH; Lee SY Anti-metastatic effect of cantharidin in A549 human lung cancer cells. Arch. Pharm. Res 2013, 36, 479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan Y; Zheng Q; Ni W; Wei Z; Yu S; Jia Q; Wang M; Wang A; Chen W; Lu Y Breaking glucose transporter 1/pyruvate kinase M2 glycolytic loop is required for cantharidin inhibition of metastasis in highly metastatic breast cancer. Front. Pharmacol 2019, 10, 590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng LH; Bao YL; Wu Y; Yu CL; Meng XY; Li YX Cantharidin reverses multidrug resistance of human hepatoma HepG2/ADM cells via downregulation of P-glycoprotein expression. Cancer Lett. 2008, 272, 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun X; Cai X; Yang J; Chen J; Guo C; Cao P Cantharidin overcomes imatinib resistance by depleting BCR-ABL in chronic myeloid leukemia. Mol. Cells 2016, 39, 869–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li C-C; Yu F-S; Fan M-J; Chen Y-Y; Lien J-C; Chou Y-C; Lu H-F; Tang N-Y; Peng S-F; Huang W-W; Chung J-G Anticancer effects of cantharidin in A431 human skin cancer (epidermoid carcinoma) cells in vitro and in vivo. Environ. Toxicol 2017, 32, 723–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang X; Lin C; Chan W; Liu K; Lu A; Lin G; Hu R; Shi H; Zhang H; Yang Z Dual-functional liposomes with carbonic anhydrase IX antibody and BR2 peptide modification effectively improve intracellular delivery of cantharidin to treat orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma mice. Molecules 2019, 24, 3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu M; Shi X; Gong Z; Su Q; Yu R; Wang B; Yang T; Dai B; Zhan Y; Zhang D; Zhang Y Cantharidin treatment inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma development by regulating the JAK2/STAT3 and PI3K/Akt pathways in an EphB4-dependent manner. Pharmacol. Res 2020, 158, 104868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H-C; Xia Z-H; Chen Y-F; Yang F; Feng W; Cai H; Mei Y; Jiang Y-M; Xu K; Feng D-X Cantharidin inhibits the growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells by suppressing autophagy and inducing apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Cell. Physiol. Biochem 2017, 43, 1829–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu M-D; Liu L; Wu M-Y; Jiang M; Shou L-M; Wang W-J; Wu J; Zhang Y; Gong F-R; Chen K; Tao M; Zhi Q; Li W The combination of cantharidin and antiangiogenic therapeutics presents additive antitumor effects against pancreatic cancer. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahu PK; Tomar RS The natural anticancer agent cantharidin alters GPI-anchored protein sorting by targeting Cdc1-mediated remodeling in endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem 2019, 294, 3837–3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Efferth T; Rauh R; Kahl S; Tomicic M; Böchzelt H; Tome ME; Briehl MM; Bauer R; Kaina B Molecular modes of action of cantharidin in tumor cells. Biochem. Pharmacol 2005, 69, 811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Y-P; Li L; Xu L; Dai E-N; Chen W-D Cantharidin suppresses cell growth and migration, and activates autophagy in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol. Lett 2018, 15, 6527–6532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song M; Wang X; Luo Y; Liu Z; Tan W; Ye P; Fu Z; Lu F; Xiang W; Tang L; Yao L; Nie Y; Xiao J Cantharidin suppresses gastric cancer cell migration/invasion by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway via CCAT1. Chem. Biol. Interact 2020, 317, 108939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen C-C; Chueh F-S; Peng S-F; Huang W-W; Tsai C-H; Tsai F-J; Huang C-Y; Tang C-H; Yang J-S; Hsu Y-M; Yin M-C; Huang Y-P; Chung J-G Cantharidin decreased viable cell number in human osteosarcoma U-2 OS cells through G2/M phase arrest and induction of cell apoptosis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem 2019, 83, 1912–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng S; Zhu J; Xia K; Yu W; Wang Y; Wang J; Li F; Yang Z; Yang X; Liu B; Tao H; Liang C Cantharidin inhibits anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins and induces apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cell lines MG-63 and MNNG/HOS via mitochondria-dependent pathway. Med. Sci. Monit 2018, 24, 6742–6749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim JA; Kim Y; Kwon B-M; Han DC The natural compound cantharidin induces cancer cell death through inhibition of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) and Bcl-2-associated athanogene domain 3 (BAG3) expression by blocking heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) binding to promoters. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 28713–28726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu J; Liu T; Rios Z; Mei Q; Lin X; Cao S Heat shock proteins and cancer. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2017, 38, 226–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Calderwood SK Heat shock proteins and cancer: Intracellular chaperones or extracellular signalling ligands? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2018, 373, 20160524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Polettini A; Crippa O; Ravagli A; Saragoni A A fatal case of poisoning with cantharidin. Forensic Sci. Int 1992, 56, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Worthley LIG Clinical toxicology: Part II. Diagnosis and management of uncommon poisonings. Crit. Care Resuscit 2002, 4, 216–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang C-C; Wu C-H; Hsieh K-J; Yen K-Y; Yang L-L Cytotoxic effects of cantharidin on the growth of normal and carcinoma cells. Toxicology 2000, 147, 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moed L; Shwayder TA; Chang MW Cantharidin revisited: A blistering defense of an ancient medicine. Arch. Dermatol 2001, 137, 1357–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chang C-C; Liu D-Z; Lin S-Y; Liang H-J; Hou W-C; Huang W-J; Chang C-H; Ho F-M; Liang Y-C Liposome encapsulation reduces cantharidin toxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol 2008, 46, 3116–3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou L; Zou M; Zhu K; Ning S; Xia X Development of 11-DGA-3-O-gal-modified cantharidin liposomes for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecules 2019, 24, 3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu K; Zhou L; Zou M; Ning S; Liu S; Zhou Y; Du K; Zhang X; Xia X 18-GA-Suc modified liposome loading cantharidin for augmenting hepatic specificity: Preparation, characterization, antitumor effects, and liver-targeting efficiency. J. Pharm. Sci 2020, 109, 2038–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guo Z; Liu Y; Cheng X; Wang D; Guo S; Jia M; Ma K; Cui C; Wang L; Zhou H Versatile biomimetic cantharidin-tellurium nanoparticles enhance photothermal therapy by inhibiting the heat shock response for combined tumor therapy. Acta Biomater. 2020, 110, 208–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zheng K; Chen R; Sun Y; Tan Z; Liu Y; Cheng X; Leng J; Guo Z; Xu P Cantharidin-loaded functional mesoporous titanium peroxide nanoparticles for non-small cell lung cancer targeted chemotherapy combined with high effective photodynamic therapy. Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 1476–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Graziano MJ; Casida JE Comparison of the acute toxicity of endothall and cantharidic acid on mouse liver in vivo. Toxicol. Lett 1987, 37, 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang S-Y; Cao K-Y The antitumor activity and clinical application of norcantharidin. Int. J. Lab. Med 2007, 28, 235–237. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pan M-S; Cao J; Fan Y-Z Insight into norcantharidin, a small-molecule synthetic compound with potential multi-target anticancer activities. Chin. Med 2020, 15, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ma Q; Feng Y; Deng K; Shao H; Sui T; Zhang X; Sun X; Jin L; Ma Z; Luo G Unique responses of hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma cell lines toward cantharidin and norcantharidin. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 2183–2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fan Y-Z; Fu J-Y; Zhao Z-M; Chen C-Q Effect of norcantharidin on proliferation and invasion of human gallbladder carcinoma GBC-SD cells. World J. Gastroenterol 2005, 11, 2431–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shi X; Chen S; Zhang Y; Xie W; Hu Z; Li H; Li J; Zhou Z; Tan W Norcantharidin inhibits the DDR of bladder cancer stem-like cells through cdc6 degradation. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 4403–4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang P-Y; Hu D-N; Kao Y-H; Lin I-C; Chou C-Y; Wu Y-C Norcantharidin induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells through both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Pharmacol. Rep 2016, 68, 874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Han Z; Li B; Wang J; Zhang X; Li Z; Dai L; Cao M; Jiang J Norcantharidin inhibits SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell growth by induction of autophagy and apoptosis. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat 2017, 16, 33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang Q-Y; Yue X-Q; Jiang Y-P; Han T; Xin H-L FAM46C is critical for the anti-proliferation and pro-apoptotic effects of norcantharidin in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mei L; Sang W; Cui K; Zhang Y; Chen F; Li X Norcantharidin inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis via c-Met/Akt/mTOR pathway in human osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 582–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang L; Ji Q; Liu X; Chen X; Chen Z; Qiu Y; Sun J; Cai J; Zhu H; Li Q Norcantharidin inhibits tumor angiogenesis via blocking VEGFR2/MEK/ERK signaling pathways. Cancer Sci. 2013, 104, 604–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cimmino F; Scoppettuolo MN; Carotenuto M; De Antonellis P; Dato VD; De Vita G; Zollo M Norcantharidin impairs medulloblastoma growth by inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. J. Neurooncol 2012, 106, 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang W-J; Wu M-Y; Shen M; Zhi Q; Liu Z-Y; Gong F-R; Tao M; Li W Cantharidin and norcantharidin impair stemness of pancreatic cancer cells by repressing the β-catenin pathway and strengthen the cytotoxicity of gemcitabine and erlotinib. Int. J. Oncol 2015, 47, 1912–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang Y; Jiang W; Li C; Xiong X; Guo H; Tian Q; Li X Autophagy suppression accelerates apoptosis induced by norcantharidin in cholangiocarcinoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res 2020, 26, 1697–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hong K-O; Ahn C-H; Yang I-H; Han J-M; Shin J-A; Cho S-D; Hong SD Norcantharidin suppresses YD-15 cell invasion through inhibition of FAK/paxillin and F-actin reorganization. Molecules 2019, 24, 1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang S; Yang Y; Hua Y; Hu C; Zhong Y NCTD elicits proapoptotic and antiglycolytic effects on colorectal cancer cells via modulation of Fam46c expression and inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling. Mol. Med. Rep 2020, 22, 774–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 88.Puerto Galvis CE; Vargas Méndez LY; Kouznetsov VV Cantharidin-based small molecules as potential therapeutic agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des 2013, 82, 477–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ye M; Zhu X; Yan R; Hui J; Zhang J; Liu Y; Li X Sodium demethylcantharidate induces apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via ER stress. Am. J. Transl. Res 2019, 11, 3150–3158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yin FL; Zhu JJ; Hao J; Cui JR; Yang JJ Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure and antitumor activities of a novel demethylcantharidato bridged copper(II) phenanthroline complex. Sci. Chin. Chem 2013, 56, 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhao C; Jia J; Wang X; Luo C; Wang Y Synthesis of norcantharidin complex salts. J. Heterocyclic Chem 2019, 56, 1567–1570. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kawamura N; Li Y-M; Engel JL; Dauben WG; Casida JE Endothall thioanhydride: Structural aspects of unusually high mouse toxicity and specific binding site in liver. Chem. Res. Toxicol 1990, 3, 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McCluskey A; Bowyer MC; Collins E; Sim ATR; Sakoff JA; Baldwin ML Anhydride modified cantharidin analogues: Synthesis, inhibition of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A and anticancer activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2000, 10, 1687–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shan H-B; Cai Y-C; Liu Y; Zeng W-N; Chen H-X; Fan B-T; Liu X-H; Xu Z-L; Wang B; Xian L-J Cytotoxicity of cantharidin analogues targeting protein phosphatase 2A. Anticancer Drugs 2006, 17, 905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yeh C-B; Su C-J; Hwang J-M; Chou M-C Therapeutic effects of cantharidin analogues without bridging ether oxygen on human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2010, 45, 3981–3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang S-C; Chow J-M; Chien M-H; Lin C-W; Chen H-Y; Hsiao P-C; Yang S-F Cantharidic acid induces apoptosis of human leukemic HL-60 cells via c-Jun N-terminal kinase-regulated caspase-8/−9/−3 activation pathway. Environ. Toxicol 2018, 33, 514–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lin P-Y; Shi S-J; Shu H-L; Chen H-F; Lin C-C; Liu P-C; Wang L-F A simple procedure for preparation of N-thiazolyl and N-thiadiazolylcantharidinimides and evaluation of their cytotoxicities against human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Bioorg. Chem 2000, 28, 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kok SHL; Chui CH; Lam WS; Chen J; Lau FY; Cheng GYM; Wong RSM; Lai PPS; Leung TWT; Tang JCO; Chan ASC Apoptotic activity of a novel synthetic cantharidin analogue on hepatoma cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Med 2006, 17, 945–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kok SHL; Chui CH; Lam WS; Chen J; Lau FY; Wong RSM; Cheng GYM; Tang WK; Cheng CH; Tang JCO; Chan ASC Mechanistic insight into a novel synthetic cantharidin analogue in a leukemia model. Int. J. Mol. Med 2006, 18, 375–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hizartzidis L; Gilbert J; Gordon CP; Sakoff JA; McCluskey A Synthesis and cytotoxicity of octahydroepoxyisoindole-7-carboxylic acids and norcantharidin-amide hybrids as norcantharidin analogues. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 1152–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ho Y-P; To KKW; Au-Yeung SCF; Wang X; Lin G; Han X Potential new antitumor agents from an innovative combination of demethylcantharidin, a modified traditional Chinese medicine, with a platinum moiety. J. Med. Chem 2001, 44, 2065–2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.To KKW; Wang X; Yu CW; Ho Y-P; Au-Yeung SCF Protein phosphatase 2A inhibition and circumvention of cisplatin cross-resistance by novel TCM-platinum anticancer agents containing demethylcantharidin. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2004, 12, 4565–4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pang S-K; Yu C-W; Au-Yeung SCF; Ho Y-P DNA damage induced by novel demethylcantharidin-integrated platinum anticancer complexes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2007, 363, 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tang Z-B; Chen Y-Z; Zhao J; Guan X-W; Bo Y-X; Chen S-W; Hui L Conjugates of podophyllotoxin and norcantharidin as dual inhibitors of topoisomerase II and protein phosphatase 2A. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2016, 123, 568–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhao CK; Xu L; Wang XH; Bao YJ; Wang Y Synthesis of dual target CPT-ala-nor conjugates and their biological activity evaluation. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem 2019, 19, 502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chi J; Jiang Z; Qiao J; Zhang W; Peng Y; Liu W; Han B Antitumor evaluation of carboxymethyl chitosan based norcantharidin conjugates against gastric cancer as novel polymer therapeutics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2019, 136, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cetintas VB; Batada NN Is there a causal link between PTEN deficient tumors and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment? J. Transl. Med 2020, 18, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhou P; Shaffer DR; Alvarez Arias DA; Nakazaki Y; Pos W; Torres AJ; Cremasco V; Dougan SK; Cowley GS; Elpek K; Brogdon J; Lamb J; Turley SJ; Ploegh HL; Root DE; Love JC; Dranoff G; Hacohen N; Cantor H; Wucherpfennig KW In vivo discovery of immunotherapy targets in the tumor microenvironment. Nature 2014, 506, 52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yakisich JS Challenges and limitations of targeting cancer stem cells and/or the tumour microenvironment. Drugs Ther. Studies 2012, 2, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Young DK Cantharidin and insects: An historical review. Great Lakes Entomologist 1984, 17, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ghoneim K Cantharidin toxicosis to animal and human in the world: A review. Stand. Res. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci 2013, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Woodward RB; Loftfield RB The structure of cantharidin and the synthesis of desoxycantharidin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1941, 63, 3167–3171. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zehnder M; Thewalt U Structure of cantharidin, C10H12O4. Helv. Chim. Acta 1977, 60, 740–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Verma AK; Prasad SB; Kaliyappan RK; Arjun J Crystal structure of cantharidin (2,6-dimethyl-4,10-dioxatricyclo-[5.2.1.02,6] decane-3,5-dione) isolated from red headed blister beetle, Epicauta hirticornis. Int. J. Bioassays 2013, 2, 527–530. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Newman DJ; Cragg GM Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod 2020, 83, 770–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kinghorn AD; Carcache de Blanco EJ; Chai H-B; Orjala J; Farnsworth NR; Soejarto DD; Oberlies NH; Wani MC; Kroll DJ; Pearce CJ; Swanson SM; Kramer RA; Rose WC; Fairchild CR; Vite GD; Emanuel S; Jarjoura D; Cope FO Discovery of anticancer agents of diverse natural origin. Pure Appl. Chem 2009, 81, 1051‒1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kinghorn AD; Carcache de Blanco EJ; Lucas DM; Rakotondraibe HL; Orjala J; Soejarto DD; Oberlies NH; Pearce CJ; Wani MC; Stockwell BR; Burdette JE; Swanson SM; Fuchs JR; Phelps MA; Xu L; Zhang X; Shen YY Discovery of anticancer agents of diverse natural origin. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 5623‒5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]