Abstract

Cannabis and cannabinoids (such as tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol) are frequently used to relieve gastrointestinal symptoms. Cannabinoids have effects on the immune system and inflammatory responses, as well as neuromuscular and sensory functions of digestive organs, including pancreas and liver. Cannabinoids can cause hyperemesis and cyclic vomiting syndrome, but might also be used to reduce gastrointestinal, pancreatic, or hepatic inflammation, as well as to treat motility, pain, and functional disorders. Cannabinoids activate cannabinoid receptors, which inhibit release of transmitters from pre-synaptic neurons, and also inhibit diacylglycerol lipase alpha, to prevent synthesis of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoyl glycerol. However, randomized trials are needed to clarify their effects in patients; these compounds can have adverse effects on the central nervous system (such as somnolence and psychosis) or the developing fetus, when used for nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Cannabinoid-based therapies can also hide symptoms and disease processes, such as in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. It is important for gastroenterologists and hepatologists to understand cannabinoid mechanisms, effects, and risks.

Keywords: THC, CBD, anandamide, 2-AG, FAAH, DAGL, MAGL

The marijuana plant, Cannabis sativa, has been cultivated by humans for medicinal and other purposes for millennia. Cannabis contains many active compounds—the best characterized are the cannabinoids ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). Cannabis and its derivatives affect many gastrointestinal processes, via the endocannabinoid system. Clinicians encounter patients who ask about, or are already using, cannabinoids for gastrointestinal indications. We review mechanisms of cannabinoids and their therapeutic effects (for previous reviews, see ref 1), focusing on findings from clinical studies, when available.

Cannabinoid Receptors in the Digestive Tract

THC activates the G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1, also called CB1) and cannabinoid receptor 2 (CNR2, also called CB2). Cannabidiol (CBD) is an agonist at CB2. CB1 is expressed throughout the gut, mainly in myenteric and submucosal neurons, and in non-neuronal cells such as epithelial cells.2 CB2 is expressed by inflammatory and epithelial cells and, to a lesser extent, by myenteric and submucosal neurons.3,4 CB1 is also expressed in brain. Endogenous ligands (endocannabinoids) include arachidonic acid-derived lipids anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG).Cannabinoids have effects in the digestive tract5, on cholinergic, tachykininergic, or VIPergic nerves in the myenteric and submucosal plexuses; on nerve fibers in circular and longitudinal muscles; and on crypt epithelial cells. Cannabinoids have indirect effects on smooth muscle cells, via their effects on neurons.5–7 For a review of CB1 and CB2 expression, see ref.8

Biosynthesis and Inactivation

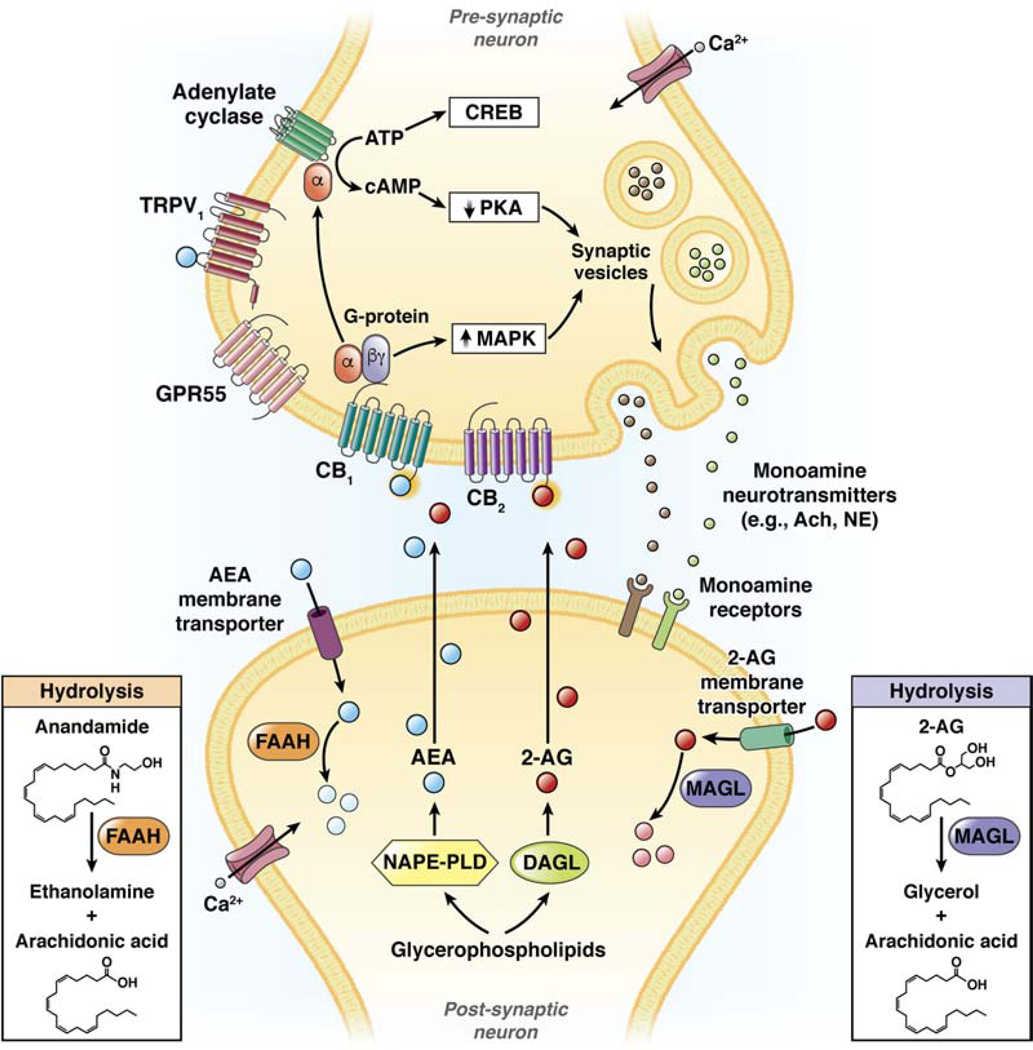

Endocannabinoids are synthesized on demand from membrane phospholipids and are released immediately after their production. For example, AEA and 2-AG are synthesized in postsynaptic neurons by enzymes such as N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D (NAPEPLD) and diacylglycerol lipase alpha (DAGLA), respectively (Figure 1). AEA, released into the synapse, functions as a retrograde messenger, binding to presynaptic CB1, whereas 2-AG binds presynsaptic CB1 and CB2. Through diverse effectors, these endocannabinoids modulate ion channels and reduce release of neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine. In addition to effects on CB1 and CB2, AEA also activates transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) on primary afferent neurons, as well as G protein-coupled receptor 55 (GPR55).9 Following induction, endocannabinoids are inactivated (Figure 1) via reuptake by putative endocannabinoid membrane transporters and degradation, by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) for AEA or monoglyceride lipase (MGLL, also called MAGL) for 2-AG.

Figure 1. Synthesis, action, and hydrolysis of endocannabinoids.

Endocannabinoids such as AEA and 2-AG are synthesized in postsynaptic neurons by synthetic enzymes such as NAPEPLD and DAGLA. Endocannabinoids are released into the synapse and bind to CB1, CB2, GPR55, and TRPV1. Through their effectors, cannabinoids reduce activity of protein kinases (such as PKA), increase activity of MAP kinases, and modulate channels and release of monoamine neurotransmitters, such as acetyl choline or norepinephrine. Endocannabinoids undergo re-uptake into the post-synaptic neuron by membrane transporters and are hydrolyzed by enzymes such as FAAH and MAGL. Reproduced with permission from reference 2.

The endocannabinoid system therefore includes CB1 and CB1, their ligands AEA and 2-AG, and the ligand-inactivating enzymes FAAH and MAGL. Exogenous (administered) cannabinoids can activate the same presynaptic receptors to modulate neurotransmitter release or sensory receptors. Cannabinoids are involved in the regulation of food intake, nausea and emesis, gastric secretion and protection, gut motility, ion transport, visceral sensation, intestinal inflammation, and proliferation of intestinal cells.10

Use and Safety Considerations

Beyond the digestive tract, cannabinoids are used for treatment of chronic pain and spasticity, nausea and vomiting due to chemotherapy, weight gain in patients with HIV infection, sleep disorders, and Tourette syndrome;11 selective cannabinoids appear to be efficacious in patients with chronic neuropathic pain.12 Cannabinoids, including cannabis, which is a partial agonist for CB1 and CB2, are used as medicinal or recreational agents. It was estimated that in 2016, 192 million people worldwide used cannabis at least once per year.13

There is widespread public perception of the efficacy of cannabinoids. However, cannabinoids use is associated with increased risk of short-term adverse events, the most frequent being tachycardia, agitation, and nausea.14 Synthetic cannabinoid products have effects that are somewhat similar to those of natural cannabis, but are more potent and longer lasting than those of THC. Some of these compounds have been linked to psychosis, mania, and suicidal ideation.15 Patients are therefore screened before and during cannabinoid treatment with validated suicide ideation questionnaires.16 Adverse consequences of the liberalization of cannabinoid use are recognized and include unintentional cannabis ingestion by children,17 in utero effects on fetal neural development associated with cannabis use during pregnancy,18 and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS).19 Given the these safety concerns, patients with history of psychosis or cardiovascular disease should not be treated with cannabinoids.20

However, there are synthetic cannabinoids with reasonable safety profiles, such as nabilone, used for nausea and pain,21 and nabiximol, used for neuropathic and malignant pain, but it is not available in the United States.22 They must still be used with caution, because nabilone can cause dizziness, dry mouth, sedation, and hallucinations.21 Nausea and vomiting are associated with use of cannabinoids. In fact, given the widespread use of cannabinoids, their effects should be considered in the differential diagnosis for neuropsychiatric or gastrointestinal signs and symptoms, and particularly when these overlap.

Esophageal Function and Diseases

In the esophagus, transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) are vago–vagally mediated inhibitions of the LES that are independent of swallowing, are triggered by various stimuli (including gastric distention), and lead to esophageal exposure to gastric acid. GABAB receptor agonists potently reduce TLESRs in patients with reflux esophagitis.23

CB1 and CB2, like GABAB receptors, are found in human nodose ganglion (the inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve), brain stem (dorsal motor nucleus and nucleus of the solitary tract), and myenteric plexus of the LES and esophagus. All of these neural elements regulate TLESRs24; given the distribution of CB1 and CB2, they might be involved in control of reflux esophagitis.

To investigate the role of cannabinoids in humans on esophageal physiology, researchers compared the effects of 10 and 20 mg of THC with placebo in 18 healthy volunteers. THC significantly reduced the number of TLESRs, LES pressure, and swallowing events, particularly in the first hour postprandially, without differences in overall esophageal acid exposure.25 However, half of the participants had nausea, confusion, dizziness, and loss of concentration. A subsequent study showed that rimonabant, an inverse agonist (a drug that binds to the same receptor as an agonist but induces a pharmacological response opposite to that of the agonist) of CB1 that is no longer marketed, due to safety issues, increased LES pressures for 2 hours postprandially and decreased TLESRs and acid reflux epiodes.26 More work is needed to characterize the roles of cannabinoids in esophageal health and disease; strategies to modify the activity of CB1 might be developed for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux.27

Nausea and Vomiting

Cannabinoid use can cause CHS and cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS). CHS is characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use.19 In a series of almost 100 patients at Mayo Clinic, approximately 75% patients had used cannabis at least 4 days per week, and approximately 68% for 2 or more years.28 A systematic review of pharmacologic treatments for CHS could not identify an optimal treatment—the review noted that benzodiazepines, followed by haloperidol and capsaicin, were most frequently effective for acute treatment and tricyclic antidepressants for long-term treatment.29

A comprehensive systematic review by Venkatesan et al, 30 from January 2000 through March 2018, identified 271 cases of CHS and elucidated patterns of use and presentation. The mean age of patients was 30.5±7.6 years, 68.6% were male, the mean duration of cannabis use prior to symptom onset was 6.6±4.3 years (with daily use in 68%), and compulsive hot-water bathing was reported for 71.5% of patients. The limited duration of follow up prevented definitive diagnoses of CHS based on Rome IV criteria. For cases with at least 4 weeks of follow up (16.2%), 86% met Rome IV criteria for CHS; 78% of case report subjects (15.7% of CHS case reports from the literature) fulfilled Rome IV criteria. This finding indicates the importance of clinician understanding of CHS and avoidance of over-reliance on diagnostic criteria—particularly in the acute care setting, in which many of these patients are first encountered. Venkatesan et al proposed novel diagnostic criteria for CHS and elements to be identified in patient histories (Table 1).30

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for CHS and Useful Information

| Proposed Diagnostic Criteria | Elements of a patient history useful for diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features: Stereotypical episodic vomiting resembling CVS in terms of onset, with a frequency three or more times annually; | Demographic information | |

| Cannabis use patterns: duration of use in year before symptom onset; frequency greater than 4 times per week, on average; | Description of vomiting episodes (onset, frequency in past year, duration of typical episode, pattern of and response to hot water bathing, duration in inter-episodic symptom quiescence | |

| Cannabis cessation: Resolution of symptoms following a period of abstinence (at least 6 months, or at least equal to the total duration of 3 typical vomiting cycles in that patient) | Description of cannabis use (duration preceding symptom onset, frequency, type and potency, route) | |

| Comorbid conditions (anxiety, depression, pain disorder, migraine) | ||

| Prior treatment and response | ||

| Follow-up periods defined by absolute time (such as at least 6 months) or by a duration of time defined by patient cycle length (for example, at least 3 successive cycles in an individual patient) | ||

| Periods of abstinence confirmed by urine toxicology analysis, when reasonable |

Note: adapted from ref. 30

CVS is prevalent (10.8%) among patients presenting to outpatient gastroenterology clinics with intermittent episodes of nausea and vomiting. CVS is associated with younger age, tobacco smoking, psychiatric comorbidity, and symptoms compatible with other functional gastrointestinal disorders.31 In a cross-sectional study of 140 patients with CVS (72% female; mean age, 37±13 years) at a specialized clinic, 41% were current cannabis users and 21% reported regular use. Regular users were more likely to be male, to report an anxiety diagnosis, and to smoke cannabis with higher THC content, for a longer duration. Most users reported that cannabis helped control CVS symptoms, and abstinence rarely resolved the CVS episodes.32 For patients with CHS and CVS, there are reports of efficacy of the tachykinin receptor 1 (NK1R) antagonist aprepitant.33,34

Cannabis is used to relieve nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP), although there is evidence that cannabis can aggravate NVP. In a study of 220,510 pregnant women (2009–2016), of which 17.6% had a diagnosis of NVP, the rate of cannabis use was about 2-fold higher among the women with nausea and vomiting. Use of marijuana increased over time in the pregnant women with nausea and vomiting, and was higher than in pregnant women without nausea and vomiting.35 Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses found association between marijuana use and adverse perinatal outcomes, especially with heavy marijuana use (such as growth restriction, stillbirth, spontaneous preterm birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission).36 Women are therefore advised to refrain from using marijuana during pregnancy and lactation.36

Gastrointestinal Motility

In addition to the role of cannabinoids in CVS and CHS, gastrointestinal dysmotilities have been associated with altered expression or activity of CB1 and CB2. Decreased enteric activity of FAAH has been associated with colonic inertia in slow transit constipation; conversely, CB1 expression appears to be non-significantly increased.37 The orphan G protein-coupled receptor, GPR55, is a target of AEA and CBD (Figure 1); there was increased expression of GPR55 in a streptozotocin mouse model of gastroparesis, so cannabinoids might inhibit gastric motility.38

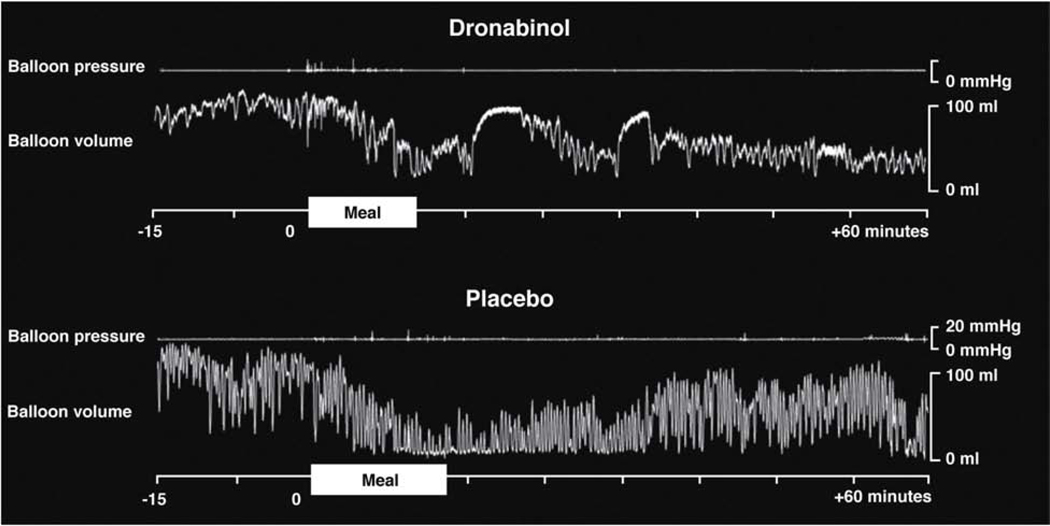

Most observations on the effects of cannabinoids on human gut motility and sensation have come from studies of dronabinol (Marinol), a synthetic THC and non-selective agonist of CB1 and CB2. Dronabinol delays gastric emptying of solids39, predominantly in women, with no significant effects on postprandial gastric accommodation, satiation, or postprandial symptoms during nutrient drink tests. Animal and in vitro studies found that cannabinoids inhibit colonic contractility.40 The DAGL inhibitors orlistat and OMDM-188 (which inhibit synthesis of endocannabinoids) accelerated colonic transit in mice, potentially providing a novel approach to relieve constipation.41 This is consistent with the human studies showing that dronabinol inhibited postprandial colonic motility and tone (Figure 3).42 Activation of CB1 receptors therefore inhibits motility, and can be increased when there is inhibition of degradative enzymes, or reversed by inhibition of endocannabinoid synthesis.

Figure 3. Effect of dronabinol on colonic tone and phasic pressure activity measured with intracolonic device.

Dronabinol inhibits postprandial phasic contractility and tone (reduced volume under barostat conditions. Treatment with dronabinol was associated with reduced reductions in the barostat balloon volume and no changes in phasic pressure responses of the colon following food ingestion. In contrast, the tone (baseline volume reduction) and phasic pressure response to the meal were significantly increased in the participant who received placebo. Reproduced from ref. 42.

On the other hand, a survey study of community-dwelling adults in the United States associated recent use of marijuana with decreased odds of constipation, defined by the Bristol stool form scale types 1 and 2 or less than 3 bowel movements per week.43 Further studies are needed to determine the effects of cannabinoids on constipation, including slow-transit constipation.

Gastroparesis

Fifty-nine of 506 (11.7%) patients with symptoms of gastroparesis (idiopathic or diabetic) in the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium database reported current marijuana use. Patients with severe nausea and abdominal pain were more likely to use marijuana and perceived it to be beneficial for their symptoms.44

A study of 24 patients with gastroparesis and refractory symptoms reported that those who had been prescribed marijuana had statistically significant improvements in every gastroparesis cardinal symptom index subgroup score, as well as in abdominal pain score.45 The possible benefits associated with marijuana use in this study were unlikely related to agonism of CB1, because gastric emptying of liquids in mice was reduced by AEA, and because rimonabant46 and dronabinol slow gastric emptying of solids.39 Placebo-controlled trials are underway to determine the effects of cannabinoids on nausea in patients with gastroparesis or functional dyspepsia (NCT03941288 for dronabinol and NCT03941288 for CBD). Cannabis-related improvement in symptoms in patients with gastroparesis could be unrelated to change in gastric emptying time. Increases in fasting gastric volume observed in healthy volunteers39 and effects on visceral sensation10 indicate that alternative mechanisms could contribute to improvements in symptoms.

Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD)

Changes in activity of CB1 and CB2 have been associated with development of IBD (see ref 47 for a review). There have been many studies of endocannabinoids and CB1 and CB2 human ileum and colon and their associations with IBD (see Table 2). CB1 and CB1 might be targeted for treatment of IBD—these receptors protect against colon inflammation in rodents48 and humans49, stimulate appetite, and relieve visceral pain1. CBD reduces permeability of the human colon, in colonic mucosa studied in vitro and in clinical studies (based on lactulose-mannitol test), compared with controls.49

Table 2.

Changes in Cannabinoid Proteins Associated With Crohn’s Disease or Ulcerative Colitis

| CB1 | CB2 | AEA | 2-AG or Palmitoylet hanolamide | NAPEPLD | FAAH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Colon | ||||||

| Colon | present | present | NA | NA | NA | present |

| Crohn’s disease, colon | ||||||

| Inflamed | present | present | NA | NA | ||

| Inflamed vs non-inflamed | ↑ | no change | ↓ | no change | no change | ↑ |

| Non-inflamed vs healthy | no change | no change | no change | no change | no change | no change |

| Crohn’s disease, ileum | ||||||

| Inflamed vs healthy | ↓ | ↓ | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Non-inflamed vs healthy | ↓ | ↓ | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| ulcerative colitis | ||||||

| Inflamed | present | present | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Inflamed vs non-inflamed | ↑ | no change | ↓ | no change | ↓ | ↑ |

| Inflamed vs healthy # | ↑, ↓, or no change | ↑ or no change | ↑ | ↑ or no change | ↓ | no change |

| Non-inflamed/Quiescent vs. healthy & | ↓ or no change | no change | no change | no change | no change | no change |

Note: Adapted from figure in ref. 47

NA, not applicable

DAGLA and MAGL increased and no change in DAGLB

DAGLA and DAGLB no Δ; increased MAGL

Patients with IBD have greater and earlier use of cannabis compared to age- and sex-matched controls;50 6.8% to 17.6% of patients with IBD use cannabis.50 Despite symptom relief, cannabis does not necessarily induce IBD remission; in fact, based on population studies, cannabis appears to be a predictor for need for operative intervention in Crohn’s disease.51 Although descriptive or open-label studies have suggested benefits of cannabinoids (including THC or cannabis) on symptoms and quality of life in IBD, the three prospective randomized, placebo-controlled trials52−54 showed little to no evidence of efficacy (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trials of Cannabinoids for IBD

| IBD | Cannabinoid used and trial duration | Numbers of patients | Primary outcome | Other comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unresponsive Crohn’s disease | Inhaled (cigarettes) containing 115 mg THC for 8 weeks | 21 | ↓ CDAI score <150 not achieved | ↓ CDAI score <100 achieved in 10/11 vs 4/10 with placebo; improved quality of life | 52 |

| Unresponsive, CDAI > 200 | 10 mg CBD Twice daily, oral, for 8 weeks | 20 | No change in DAI of CBD vs placebo at 8 weeks and 2 weeks later | no difference in adverse events between CBD and placebo groups | 53 |

| Left-sided ulcerative colitis on 5-ASA, Mayo score 4–10 | 50 mg CBD-rich botanical extract for 10 weeks | 60 | No change in number achieving Mayo score <2 in ITT analysis | 39 completers; 21 withdrew, 15 due to AEs (10 on CBD); PP analysis of total and partial Mayo ulcerative colitis scores and pain indicated efficacy of CBDrich botanical extract | 54 |

5-ASA, 5-amino salicylic acid; CDAI, Crohn’s disease activity index; ITT = intention to treat; PP = per protocol

Management of pain in particular is a challenge in patients with IBD. Opiates increase risk of death, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can induce bowel strictures and ulcers that mimic IBD. The effects of the CB2 agonist olorinab (25 or 100 mg, 3 times daily for up to 8 weeks) were studied in an open-label, parallel-group, multicenter, phase 2a study of 14 patients with quiescent Crohn’s disease and average weekly abdominal pain. Patients were randomly assigned to groups given the doses of olorinab; average abdominal pain scores were lower at weeks 4 and 8 compared with baseline. Olorinab also increased numbers of pain-free days/week, and reduced daily bowel movements.55 Comparator-controlled studies are awaited.

Pancreas

For a review of cannabinoids in the endocrine pancreas, see ref 56. CB1 and CB2 are expressed by alpha and beta cells of the endocrine pancreas, aiding in the release of insulin.57 There have been few studies of acute pancreatitis in humans. In mice with cerulein-induced pancreatitis, Activation of CB1 increased disease activity, in contrast to the protective effect of CB1 agonists in models of gastritis.58 Conversely, in mice with acute pancreatitis, CB1 and CB2 agonists or selective agonists of CB2 reduced pain, pain-related behavior, inflammation, and tissue damage.59 Further studies are needed in animal models of acute pancreatitis, especially in view of rare cases of acute pancreatitis in humans on THC use; mechanisms resulting in pancreatitis in these cases remain unclear.60

Studies of chronic pancreatitis, in contrast, have provided insight into the roles of cannabinoids in development of pancreatic disease. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study tested namisol (which contains pure, natural THC) in patients with chronic pancreatitis for 50–52 days and showed no change in inflammatory (tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 8 [IL8]) and anti-inflammatory (IL10) cytokines compared to baseline.61 Another study showed that THC did not significantly reduce pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis.62 Data from epidemiology studies indicated the potential of cannabis to reduce opioid use in chronic pancreatitis. Therefore, 53 patients with chronic pancreatitis on opioid therapy who enrolled in state therapeutic cannabis programs showed a trend toward decreased daily average opioid use, decreased hospital admissions, and decreased emergency department visits compared with those not enrolled.63 Further studies in larger cohorts are needed to test the hypothesis that medical cannabis may be an effective adjunctive therapy to replace or minimize chronic opioid therapy for pain in chronic pancreatitis.

Anti-growth and pro-apoptotic properties have been observed in in vitro appraisals of cannabinoids in models of pancreatic cancer.64 There are no clinical studies showing benefits from cannabinoid use in pancreatic malignancy.

Liver Disease

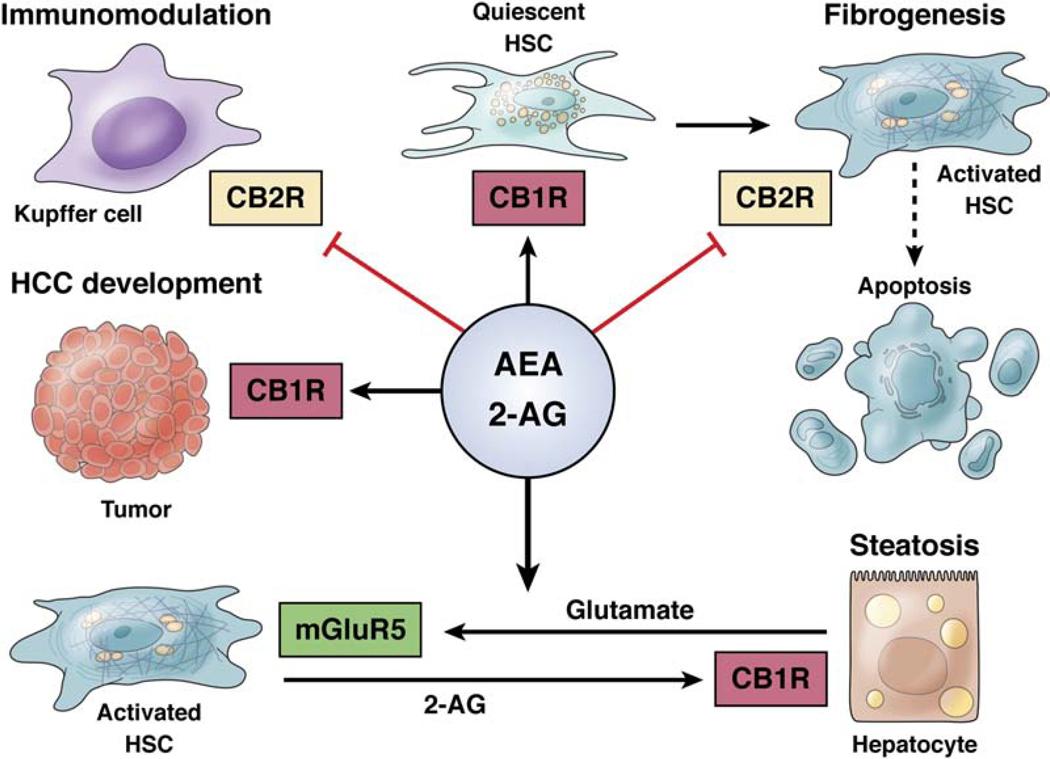

2-AG and AEA have effects on development of liver diseases (see Figure 2).65 CB1 and CB2 are expressed in healthy liver; CB1 is expressed by endothelial cells and hepatocytes and CB2 is expressed by Kupffer cells. Endocannabinoids have multiple effects in the liver 66—they inhibit the inflammatory response mediated by Kupffer cells, by binding to CB2; promote fibrogenesis by activating quiescent hepatic stellate cells (mediated by binding to CB1 and inhibited by binding to CB2); induce apoptotic pathways in hepatocytes via CB1; and increase lipogenesis and hepatic steatosis (due to alcohol), via 2-AG binding to CB1 on hepatocytes.

Figure 2. Pathogenic roles of endocannabinoids in liver diseases.

Reproduced with permission from ref. 66.

Activation of CB1 on hepatocytes promotes liver regeneration and immune tolerance to hepatocellular carcinoma. This occurs via 2-AG synthesis in hepatic stellate cells, activated by hepatocyte-derived glutamate. This findings indicates communication between hepatocytes and stellate cells.67

The effects of cannabinoids have been studied in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) or HCV infection, and autoimmune hepatitis, as well as in animal models of these diseases. Endocannabinoids and their receptors are upregulated in hepatic tissues in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or cirrhosis, compared to patients without liver disease. In rodents, CB2 agonists reduced liver inflammation and fibrosis (for review, see ref 68).

Rimonabant reduced liver regeneration, portal pressure, and ascites in rodents with cirrhosis (reviewed in ref. 69). In patients with chronic HBV infection, levels of CB1 and CB2 increased with the degree of fibrosis70; these receptors were expressed by activated hepatic stellate cells involved in fibrosis.71 Similarly, in patients with chronic HCV infection, increased CB1 expression was associated with fibrosis stage and cirrhosis, as well as increased steatosis, in association with HCV genotype 3 infection.72 Cannabis use (particularly daily use) was also associated with steatosis, fibrosis, and odds of developing encephalopathy.73 Paradoxically, patients with HIV and HCV co-infection had lower risk of insulin resistance and steatosis with daily cannabis use.74,75 Cannabinoids might be manipulated for treatment of autoimmune hepatitis, based on studies from animal models,76 but studies in humans are needed.

Pain, Nausea, and Vomiting Disorders

The cannabinoids approved by the Food and Drug Administration are dronabinol, for treatment of anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS or nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, and CBD (Epidiolex, a selective agonist of CB2), for treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome (in patients 2 years or older). Nabilone (Casamet, a synthetic cannabinoid with a structure similar to that of THC), is used as an antiemetic and an analgesic for neuropathic pain.

Reviewing the information and published data on the role of cannabinoids, CB1 and interactions with sensory neurotransmitters (such as substance P, CGRP, and TRPV1), Sharkey and Wiley proposed that peripherally-restricted cannabinoids and modulators of endocannabinoid synthesis and/or degradation might be effective for short-term treatment of symptoms associated with functional bowel disorders.10 Administration of THC, 3 times daily for approximately 7 weeks, to patients with chronic abdominal pain after surgery did not reduce pain measures, compared with placebo, although THC was safe and well tolerated. Similarly, THC did not reduce post-operative pain compared with placebo.77

Other cannabinoid agents might be used to relieve pain, although the jury is still out regarding the benefit:risk ratio. A systematic review that included 24 randomized, controlled trials and 1334 patients concluded that, although some randomized trials reported significant a decrease in pain scores, most studies did not show an effect on pain,78 possibly indicating an effect on well-being or mood, rather than pain sensation.

A Cochrane review79 concluded that potential benefits of cannabis-based medicines (herbal cannabis, plant-derived or synthetic THC, or a THC and CBD oromucosal spray) in chronic neuropathic pain might be outweighed by their potential harms. A brain imaging study80 showed that different cannabinoid-based drugs had heterogeneous effects on brain images, anxiety, and pain perception. THC increased anxiety and levels of intoxication, sedation, and psychotic symptoms, whereas CBD reduced anxiety and activation in affective (amygdala and the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex), but not sensory, centers associated with perception of pain (such as frontal and somatic cortex).80

Cremon et al 81 examined the effects of 200 mg palmithoylethanolamide, which has structural features of AEA) and 20 mg polydatin (which reduces mast cell activation through synergistic activity with palmithoylethanolamide) on adults subjects with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter, double-blinded pilot study over 12 weeks. Palmithoylethanolamide/polydatin significantly reduced abdominal pain, compared with placebo, with a similar safety profile to that of placebo. In addition, the colonic mucosa of patients with IBS was found to be enriched in CB2 receptor compared to controls, leading to the hypothesis that the endocannabinoid system may influence the mechanisms of IBS.82

Nausea and Vomiting Syndromes

The effects of chronic stress on peripheral endocannabinoid pathways in visceral primary afferent neurons and in the brain, including mechanisms involved in nausea and vomiting, are reviewed elsewhere.10 The effects of cannabinoids have been studied in people with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) who respond poorly to commonly used antiemetic agents. In systematic review of 23 randomized trials,83 researchers found no differences between treatment with cannabinoids and prochlorperazine, although the quality of evidence was graded as low. In addition, a higher proportion of patients receiving cannabinoids withdrew from the study, due to adverse events or lack of efficacy. Cannabinoid use was associated with dizziness, dysphoria, euphoria, feeling high, and sedation.83 Analysis of the use of cannabinoids for CINV in patients younger than 18 years old concluded that cannabinoids were probably effective, but produced frequent side effects84 including drowsiness and cognitive impairment.85

In patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiotherapy, there was no difference in the incidence of nausea, loss of appetite, or quality of life between those who received nabilone vs placebo.86 A randomized, placebo-controlled trial showed no difference in the efficacy and safety of single-dose nabilone for post-operative nausea and vomiting in patients who underwent general anesthesia for elective surgery.87 Unfortunately, most of these studies did not compare the efficacy of cannabinoids with 5-HT3 or antagonists of NK1R. Therefore, authoritative bodies recommended against the use of medical cannabinoids as first- or second-line treatment of CINV, although nabilone can be considered in the treatment of refractory CINV.88

Future Directions

Given widespread expression of CB2 in brain, peripheral nervous system, and gastrointestinal tract, selective agonists are being evaluated for analgesia; these would not have the centrally mediated effects of non-selective cannabinoids such as THC or dronabinol. Olorinab (formerly APD371) is a highly selective full agonist of CB2 and a visceral analgesic, based on studies of animal models and preliminary findings from clinical studies. Olorinab reduced pain in a rat model of pancreatitis (ref 92) and also reduced visceral hypersensitivity and the visceromotor response to colorectal distension in rats with 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis 89 and in mice with visceral hypersensitivity.73

A dose-escalation study reported that olorinab (10 mg to 400 mg oral daily) was safe and tolerable in 36 healthy adult volunteers.90 The most commonly reported adverse events were headache (7.4%) and nausea (7.4%). In patients with quiescent Crohn’s disease and average weekly abdominal pain scores of 4 or more, out of 10, there was relief of pain, daily coping, daily life, emotional effects.55 A phase 2 trial (CAPTIVATE) is underway to examine the effect of olorinab on abdominal pain in patients with IBS (NCT04043455). Non-psychotropic plant cannabinoids, including CBD, activate and rapidly desensitize TRPV1, in a dose-dependent manner, as well as TRPV2, based on patch clamp studies of transfected HEK293 cells.91

CBD acts as a direct agonist for serotonin 5-HT1A receptors as well as TRPV1 and glycine channels and is an indirect agonist at adenosine receptors and reduces pain in mice following spinal cord injury.91 Palmitoylethanolamide is an endogenous fatty acid amide that binds to a nuclear receptor and has diverse biological functions related to chronic pain and inflammation. Palmitoylethanolamide/polydatin, 20 or 200 mg twice daily, was more effective than placebo in reducing the severity of abdominal pain and discomfort in 54 patients with IBS and 12 healthy controls.81 LY3038404 HCl, a potent agonist of CB2 with analgesic properties but without effects on higher brain functions, attenuated pain in a rat model of pancreatitis.92 The oral CB2 agonist, PF-03550096 (3 and 10 mg/kg) increased the colonic pain threshold in a rat model of visceral hypersensitivity.93

Given the heterogeneity of gastrointestinal disorders that might be treated with cannabinoids, as well as the heterogeneity in cannabinoid ligand and receptor structures, a systematic approach is needed. This approach would improve the study quality, concordance, and generalizability. Studies should exclude patients with polymorphisms in CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 that significantly affect CBD metabolism (ultrafast metabolizers) and could confound assessment of its effects.94,95

In addition, when feasible, standardized, validated measurements of gastrointestinal functions96 should be included in studies of gastrointestinal diseases and cannabinoid pharmacology. These include gastric emptying (measured by scintigraphy) and gastric accommodation (measured by single-photon emission-computed tomography) in treatment of upper gut symptoms. Measurements should also include colonic transit, determined by radiopaque markers or scintigraphy, and colonic tone and sensation, measured by intracolonic balloon under barostat control, for studies of pharmacodynamics in relation to lower gastrointestinal diseases. More data are needed from humans, including appropriately processed biopsy specimens for measurement of biosynthetic enzymes, AEA, 2-AG, degradation enzymes, and CB1 and CB2. It is a technical challenge to measure these proteins in biopsy specimens, but these are important studies to perform, because few data are available.

Cannabinoids control inflammatory, motor, sensory, regenerative, and neoplastic functions in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. Gastroenterologists and hepatologists encounter the effects of cannabinoid use in patients with disorders such as CVS and CHS. Cannabinoids might be used to treated diseases including viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, or chronic pancreatitis. In addition, nausea and vomiting syndromes may be modified by self-medication or recreational use of cannabinoids. We need to understand more fully the effects of cannabinoids on gastrointestinal functions, as well as their potential roles in therapy. With the development of novel, more specific agonists and antagonists, cannabinoids might be included in pharmacologic approaches to relieve symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, inflammation, and pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Mrs. Cindy Stanislav for excellent secretarial support.

Funding: Michael Camilleri is supported by NIH grants R01-DK115950 and R01-DK122280 for studies on irritable bowel syndrome and cannabidiol respectively.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Michael Camilleri serves as an unpaid adviser to Arena Pharmaceuticals (compensation to Mayo Clinic not to him personally) and is starting single center research study of pharmacodynamics effects of olorinab in patients with irritable bowel syndrome funded by Arena. Daniel B. Maselli has no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goyal H, Singla U, Gupta U, et al. Role of cannabis in digestive disorders. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;29:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camilleri M Cannabinoids and gastrointestinal motility: Pharmacology, clinical effects, and potential therapeutics in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;30:e13370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan M, Mouihate A, Mackie K, et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors in the enteric nervous system modulate gastrointestinal contractility in lipopolysaccharide-treated rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2008;295:G78–G87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright KL, Duncan M, Sharkey KA. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors in the gastrointestinal tract: a regulatory system in states of inflammation. Br J Pharmacol 2008;153:263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan M, Davison JS, Sharkey KA. Endocannabinoids and their receptors in the enteric nervous system. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;22:667–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright K, Rooney N, Feeney M, et al. Differential expression of cannabinoid receptors in the human colon: cannabinoids promote epithelial wound healing. Gastroenterology 2005;129:437–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinds NM, Ullrich K, Smid SD. Cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptors coupled to cholinergic motorneurones inhibit neurogenic circular muscle contractility in the human colon. Br J Pharmacol 2006;148:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y, Jo J, Chung HY, et al. Endocannabinoids in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol 2016;311:G655–G666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown AJ. Novel cannabinoid receptors. Br J Pharmacol 2007;152:567–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharkey KA, Wiley JW. The role of the endocannabinoid system in the brain-gut axis. Gastroenterology 2016;151:252–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;313:2456–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng H, Johnston B, Englesakis M, et al. Selective cannabinoids for chronic neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2017;125:1638–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Drug Report 2016: Cannabis. [May;2019]; https://www.unodc.org/wdr2016/en/cannabis.html 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tait RJ, Caldicott D, Mountain D, et al. A systematic review of adverse events arising from the use of synthetic cannabinoids and their associated treatment. Clin Toxicol 2016;54:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinstein AM, Rosca P, Fattore L, et al. Synthetic cathinone and cannabinoid designer drugs pose a major risk for public health. Front Psychiatr 2017;8:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/210365lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards JR, Smith NE, Moulin AK. Unintentional cannabis ingestion in children: a systematic review. J Pediatr 2017;190:142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant KS, Petroff R, Isoherranen N, et al. Cannabis use during pregnancy: pharmacokinetics and effects on child development. Pharmacol Ther 2018;182:133–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R,et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut 2004;53:1566–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark AJ, Lynch ME, Ware M, et al. Guidelines for the use of cannabinoid compounds in chronic pain. Pain Res Manag 2005;10(Suppl.A):44A–46A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsang CC, Giudice MG. Nabilone for the management of pain. Pharmacotherapy 2016;36:273–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nabiximols for multiple sclerosis. Aust Prescr 2018;41:203–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Q, Lehmann A, Rigda R, et al. Control of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux by the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut 2002;50:19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohof WO, Aronica E, Beaumont H, et al. Localization of mGluR5, GABAB, GABAA, and cannabinoid receptors on the vago-vagal reflex pathway responsible for transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation in humans: an immunohistochemical study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:383.e173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaumont H, Jensen J, Carlsson A, et al. Effect of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, a cannabinoid receptor agonist, on the triggering of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations in dogs and humans. Br J Pharmacol 2009;156:153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scarpellini E, Blondeau K, Boecxstaens V, et al. Effect of rimonabant on oesophageal motor function in man. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gotfried J, Kataria R, Schey R. Review: The role of cannabinoids on esophageal function - what we know thus far. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2017;2:252–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simonetto DA, Oxentenko AS, Herman ML, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: A case series of 98 patients. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:114–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards JR, Gordon BK, Danielson AR,et al. Pharmacologic treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A systematic review. Pharmacotherapy 2017;37:725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Li BUK, et al. Role of chronic cannabis use: Cyclic vomiting syndrome vs cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2019;31 Suppl 2:e13606. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sagar RC, Sood R, Gracie DJ, et al. Cyclic vomiting syndrome is a prevalent and under-recognized condition in the gastroenterology outpatient clinic. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;30(1). doi: 10.1111/nmo.13174. Epub 2017 July 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkatesan T, Hillard CJ, Rein L,et al. Patterns of cannabis use in patients with cyclic vomiting syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019July25. pii: S1542–3565(19)30783–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.039. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cristofori F, Thapar N, Saliakellis E, et al. Efficacy of the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant in children with cyclical vomiting syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parvataneni S, Varela L, Vemuri-Reddy SM, et al. Emerging role of aprepitant in cannabis hyperemesis syndrome. Cureus 2019;11:e4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young-Wolff KC, Sarovar V, Tucker LY, et al. Trends in marijuana use among pregnant women with and without nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, 2009–2016. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;196:66–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metz TD, Borgelt LM. Marijuana use in pregnancy and while breastfeeding. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:1198–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang SC, Wang WL, Su PJ, et al. Decreased enteric fatty acid amide hydrolase activity is associated with colonic inertia in slow transit constipation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin XH, Wei DD, Wang HC, et al. Role of orphan G protein-coupled receptor 55 in diabetic gastroparesis in mice. Sheng Li Xue Bao 2014;66:332–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esfandyari T, Camilleri M, Ferber I, et al. Effect of a cannabinoid agonist on gastrointestinal transit and postprandial satiation in healthy human subjects: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2006;18:831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hornby PJ, Prouty SM. Involvement of cannabinoid receptors in gut motility and visceral perception. Br J Pharmacol 2004;141:1335–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bashashati M, Nasser Y, Keenan CM, et al. Inhibiting endocannabinoid biosynthesis: a novel approach to the treatment of constipation. Br J Pharmacol 2015;172:3099–3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Esfandyari T, Camilleri M, Busciglio I, et al. Effects of a cannabinoid receptor agonist on colonic motor and sensory functions in humans: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Physiol 2007;293:137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adejumo AC, Flanagan R, Kuo B, et al. Relationship between recreational marijuana use and bowel function in a nationwide cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:1894–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.