Abstract

Background:

Supportive care interventions have demonstrated benefits for both informal/family cancer caregivers and their patients, but uptake is generally poor. Little is known about the availability of supportive care services in community oncology practices, as well as engagement practices to connect caregivers with these services.

Methods:

Questions from the NCI Community Oncology Research Program's (NCORP) 2017 Landscape Survey examined caregiver engagement practices (i.e., caregiver identification, needs assessment, and supportive care service availability). Logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between the caregiver engagement outcomes and practice-group characteristics.

Results:

A total of 204 practice groups responded to each of the primary outcome questions. Only 40.2% of practice groups endorsed having a process to systematically identify and document caregivers, though 76% were routinely using assessment tools to identify caregiver needs and 63.7% had supportive care services available to caregivers. Caregiver identification was more common in sites affiliated with a critical access hospital (OR =2.44, p=.013), and assessments were less common in safety net practices (OR =0.41, p=.013). Supportive care services were more commonly available in the western region, in practices with in-patient services (OR =2.96, p=.012), and in practices affiliated with a critical access hospital (OR =3.31, p=.010).

Conclusions:

Although many practice groups provide supportive care services, less than half systematically identify and document informal cancer caregivers. Expanding fundamental engagement practices such as caregiver identification, assessment, and service provision will be critical to support recent calls to improve caregiver well-being and skills to carry out caregiving tasks.

Keywords: cancer, oncology, caregiving, supportive care, assessment

Precis for use in the Table of Contents:

Although many community oncology practice groups provide supportive care services, less than half systematically identify and document informal cancer caregivers. Expanding fundamental engagement practices such as caregiver identification, assessment, and service provision will be critical to support recent calls to improve caregiver well-being and skills to carry out caregiving tasks.

Background

There are at least 2.8 million informal (unpaid) caregivers in the US, who provide care to adult patients with a primary diagnosis of cancer.1 These caregivers report many unmet needs across psychosocial, medical, daily activity, and financial areas, and those with unmet needs report poorer mental health.2 Despite performing complex care tasks such as administering medications, managing patients’ symptom burden, and coordinating patient care, caregivers are typically not prepared and undertrained.1,3,4 Anxiety and depression are common in cancer caregivers (40% and 39%, respectively)5; compared to population norms, cancer caregivers have worse mental and physical well-being.6

In 2015, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) issued four recommendations for advancing cancer caregiving science: 1) improve the assessment of the prevalence and burden of informal cancer caregiving; 2) improve interventions targeted at cancer patients, caregivers, and patient-caregiver dyads; 3) facilitate further integration of caregivers into formal healthcare settings; and 4) maximize the positive impact of technology on informal cancer caregiving.7 A critical first step to achieving these recommendations, however, is to better understand current caregiver engagement practices in oncology settings, where supportive care has largely focused on patients.

Supportive care services for patients, such as psychosocial oncology care, pain management, integrative medicine, nutrition, and rehabilitation are considered essential comprehensive oncology care components. These services are also critical for caregivers, as supportive care interventions for cancer caregivers decrease burden and depression and improve well-being, satisfaction, knowledge and skills.8 However, little is known about the availability of supportive care interventions for caregivers in general oncology practice. To date, most literature reports unmet supportive care needs and service utilization using caregiver reports.9 There is a paucity of system-level data clarifying service availability and how oncology practices identify caregivers in need of services. This gap is a major barrier to advancing routine integration of supportive care for caregivers. One previous study examined supportive care resource availability for patients and family caregivers at 31 NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers and observed that service quantity and quality improved since 1994. 10 For example, 88% of institutions offered nutritional services for patients and 96% offered spiritual services. Additionally, 65% offered caregiver education programs and 84% offered some type of family caregiver program, but the types and scope of caregiver services were not reported.

A recent systematic review11 concluded cancer caregiver interventions show limited capacity for translation to practice. Intervention delivery required a median time commitment of staff of 180 minutes and the majority of studies failed to include key components to support future implementation (e.g., acceptability, potential adoption).11 Similarly, a meta-analysis highlighting the research to practice gaps suggested that evidenced-based supportive care interventions for caregivers are rarely implemented in practice and identified system and provider-level barriers to implementation of caregiver interventions.12 Cited barriers include insufficient provider awareness of caregivers’ needs, suboptimal provider training, emphasis on medical care, and cost12; these barriers may be particularly evident in community oncology practices where resources are often limited. No studies have assessed caregiver service availability in community oncology clinics or the presence of caregiver identification and assessment practices.

As part of a larger effort to examine cancer care delivery research capacity and priorities, our team conducted the first assessment of cancer caregiver engagement practices in community oncology practices and reports the proportion of oncology practices that: (a) identify and document caregivers, (b) assess caregiver needs, and (3) have supportive care services available for caregivers. This study also examined variation in these caregiver engagement practices by practice-level characteristics. These data will provide a benchmark to monitor future progress in supporting cancer caregivers in the US providing care for patients receiving treatment in the community oncology setting and provide a better understanding of how gaps in caregiver engagement practices vary so that interventions can be targeted appropriately.

Methods

Overview

The NCI-funded Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) supports recruitment of patients to clinical trials from a national network of community oncology clinics.13 Data for the current study were obtained from NCORP’s Cancer Care Delivery Research (CCDR) 2017 Landscape Survey. This survey solicited information on community site infrastructure and capacity for CCDR among NCORP clinics. CCDR is a multidisciplinary science that aims to the health and well-being of cancer patients and survivors by intervening on multi-level factors that influence care delivery.14 Landscape survey development and distribution to NCORP “components/subcomponents” has been previously described.15,16 The term “component/subcomponent” in the NCORP network refers to the specific community oncology practice group. Administrators and research staff at NCORP clinics answered questions via internet-based surveys on topics related to health care delivery and clinical trials. As described previously,15,16 oncology clinics were allowed to respond as a practice group, indicating that multiple clinics shared providers, patients, and infrastructure with a common electronic health record. The current study focused on three independent questions from the Landscape Survey: 1) systematic caregiver identification and documentation; 2) assessment of caregiver needs; and 3) availability of supportive care services for caregivers. This study was determined to be exempt from the Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Measures

Caregiver engagement practice questions used for the current study included: (1) Does your component/subcomponent have a mechanism in place to systematically identify and document a primary family or other informal (unpaid) caregiver for cancer patients? (response options: yes; no; no, but planning in progress); (2) Are assessment tools, such as rating scales or screening questions, used to identify the needs of informal or family caregivers at your component/subcomponent? (response options: yes, routinely collected for the majority of caregivers; yes, sometimes; no, not at all); and (3) Are supportive care services available specifically for family or other informal caregivers at your component/subcomponent? (response options: yes; no; no, but planning in progress). A follow-up question asked participants to specify what caregiver services were offered from a list of services (response options: yes; no). We developed a modified list distinguishing five supportive care service types assessed in prior studies 10,17,18 including: (1) caregiving training or education classes (e.g., assistance with ADLs, medical or nursing tasks); (2) individual psychosocial (e.g., coping support, counseling) or behavioral (e.g., smoking cessation, stress management) services for caregivers; (3) group psychosocial services (e.g., support group, other psychosocial or psychoeducation group) for caregivers; (4) self-care classes (e.g., healthy behaviors, diet/nutrition, exercise, sleep); and (5) respite care (e.g., help in getting access to community resources/services to provide caregiver relief). We additionally included a free-text option allowing respondents to report other supportive care services offered.

We also report on a sub-set of practice characteristics for each component/subcomponent including the number of new cancer cases per year (a proxy for practice group size), the organization of cancer care services (inpatient services, outpatient clinic in or on hospital campus, and free-standing outpatient clinic or private group/ practice), Commission on Cancer (COC) accreditation status, safety-net hospital status, and whether the practice group was affiliated with a critical access hospital. We excluded practice groups serving solely pediatric patients as this group and practice environment have distinct supportive care needs and infrastructure, respectively. Due to sample size restrictions and to preserve respondent anonymity, practice groups were classified into the four United States (US) Census regions including West, Midwest, Northeast, and South19 for analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Frequency statistics summarized practice-group characteristics and prevalence of the following primary outcomes: caregiver identification practices, caregiver assessment practices, and supportive care service availability for caregivers at practice groups. We also calculated the prevalence of practice groups offering each of the five supportive care services (training or education classes; group psychosocial services; individual psychosocial/ behavioral services; respite care; self-care classes) and the most common co-occurring caregiver engagement practices. Logistic regression models were used to examine the relationships between the primary outcomes and practice-group characteristics. For caregiver identification practices and supportive care service availability, answers of “no” and “no, but planning in progress” are combined to compare yes and no in the logistic regression models. For caregiver assessment practices, “routinely collected for the majority of caregivers” is compared to “sometimes” or “not at all”. Backwards selection was used to identify final models for each outcome. A significance level of 0.15 was used for a predictor to stay in the model. All analyses were conducted in SAS (v.9.4, Cary, NC) with a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Practice Group Characteristics

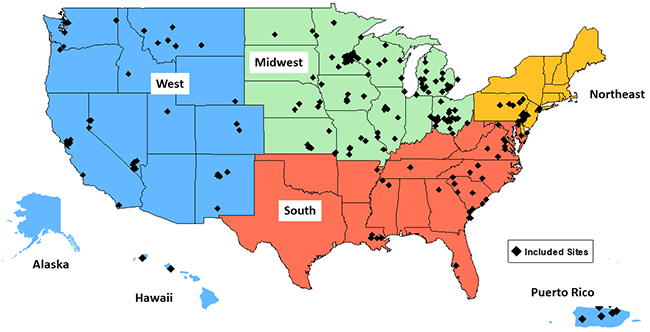

Of the 943 NCORP discrete practice locations, 504 (54%) responded to the survey, corresponding to 227 practice groups; 17 were excluded because they serve pediatric patients only. Of the remaining 210 practice groups, 204 responded to each of the primary outcome questions (See Figure 1). One hundred and six practice groups (52%) were located in the Midwest, 43 (21.1%) were in the West, 42 (20.6%) were in the South, and 13 (6.4%) were in the Northeast. See Table 1 for additional practice group characteristics.

Figure 1.

204 NCORP practice groups participated.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Practice Groups (n=204)

| Region, n (%) | |

| Midwest | 106 (52%) |

| West | 43 (21.1%) |

| South | 42 (20.6%) |

| Northeast | 13 (6.4%) |

| Number of New Cancer Cases/Year, median (IQR) | 843 (412-1690) |

| Service Organization, n (%) | |

| Inpatient services | 168 (82.8%) |

| Outpatient clinic in or on hospital campus | 168 (82.4%) |

| Free-standing outpatient clinic or private group/ practice | 123 (60.3%) |

| COC Accreditation*, n (%) | 142 (86.1%) |

| Safety-net hospital, n (%) | 48 (23.8%) |

| Affiliated with critical access hospital, n (%) | 43 (21.3%) |

Abbreviations: COM, Commission on Cancer

Only asked for those practices with inpatient services

Caregiver Identification and Needs Assessment Practices

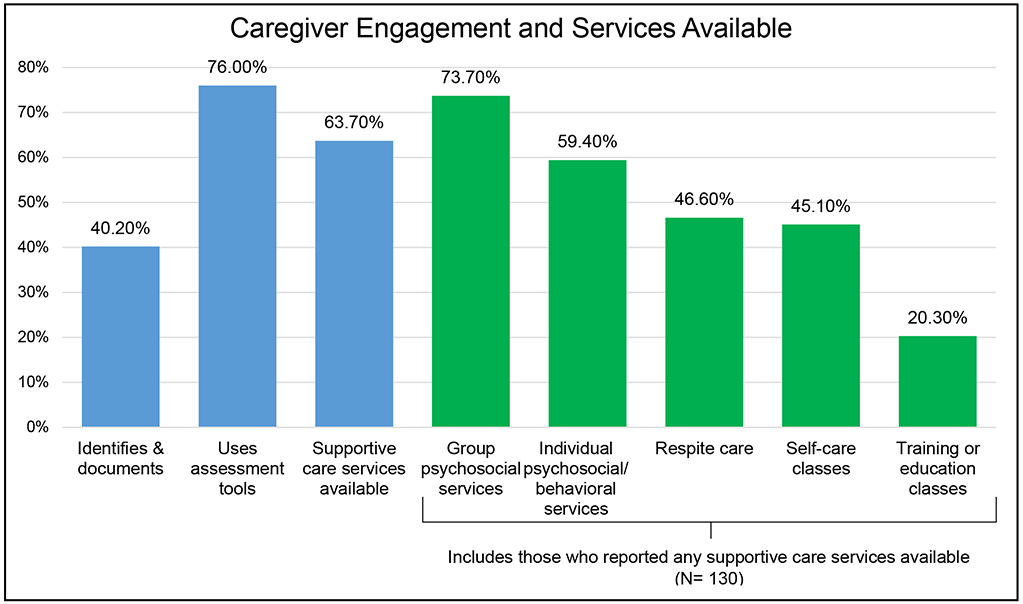

Only 40.2% (n=82) of community oncology practice groups reported they had a process in place to systematically identify and document informal caregivers (Figure 2). The majority of practice groups (76%; n=155) reported routinely using assessment tools to identify caregiver needs (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) practice groups with informal caregiver supportive care services (N= 204).

Caregiver Supportive Care Service Availability

The majority of practice groups (63.7%; n=130) had supportive care services available to caregivers (Figure 2). The most common services included group psychosocial services (73.7%; n=98 practice groups) and individual psychosocial/ behavioral services (59.4%; n=79) (Figure 2). Less than half of practice groups had available respite care programs (46.6%; n=62) and self-care classes (45.1%; n=60); less than a quarter of practice groups had available general training or educational classes for caregivers (20.3%; n=27). Among practice groups with available supportive care services, groups most commonly had two types of services (17.6%; n=36); few practice groups (5.9%; n=12) had all five services and only 2.9% (n=6) reported that they did not have any of the services. Among practice groups “routinely” or “sometimes” using assessment tools for caregivers, an average of 2 (SD=1) services were available. Patterns of caregiver practices varied with only 23.5% (n=48) of practice groups engaging in all three practices (i.e., identifying, assessing, and having available services), while 7.8% (n=16) only identified and assessed needs in caregivers.

Practice Group Differences in Caregiver Practices & Services

As shown in Table 2, caregiver practices varied by practice characteristics. Specifically, caregiver identification practices were more common in sites affiliated with a critical access hospital (OR = 2.44, p = .013). Assessment practices were less likely to be conducted in safety net hospitals (OR = 0.41, p = .013). Finally, supportive care services were more commonly available in the western region of the US, in practices with in-patient services (OR = 2.96, p = .012), and in practices affiliated with a critical access hospital (OR = 3.31, p = .010).

Table 2.

Associations between Oncology Practice Group Characteristics and Cancer Caregiver Engagement Practices (N= 204)

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Identifies & Documents Caregivers | ||

| Free-standing outpatient clinic or private group/practice (Yes vs. No) | 1.77 (0.97-3.23) | 0.061 |

| Affiliated with critical access hospital (Yes vs. No) | 2.44 (1.21-4.91) | 0.013 |

| Supportive Care Services Available for Caregivers | ||

| Region | 0.044 | |

| Midwest vs. West | 0.60 (0.26-1.41) | |

| Northeast vs. West | 0.19 (0.05-0.76) | |

| South vs. West | 0.33 (0.12-0.89) | |

| Free-standing outpatient clinic or private group/practice (Yes vs. No) | 1.76 (0.89-3.45) | 0.102 |

| Inpatient services (Yes vs. No) | 2.96 (1.28-6.89) | 0.012 |

| Affiliated with critical access hospital (Yes vs. No) | 3.31 (1.34-8.20) | 0.010 |

| Uses Assessment Tools | ||

| Safety-net hospital (Yes vs. No) | 0.41 (0.20-0.83) | 0.013 |

Discussion

This study is the first to assess the prevalence and correlates of caregiver engagement practices in a national sample of community oncology clinics. Our findings support and advance recommendations from the 2015 NCI/ NINR cancer caregiving meeting to improve caregiver assessment, interventions, and integration within the healthcare setting.7 More than half of practice groups surveyed in the NCORP Landscape Survey reported not identifying/ documenting informal caregivers. Suboptimal identification suggests a critical need for education and technical assistance to implement caregiver-tailored services. Policy support through legislations such as the Caregiver, Advise, Record, and Enable (CARE) Act may further efforts to identify and document caregivers as part of routine cancer care. The CARE Act, sponsored by the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP),20,21 in part mandates hospitals to record family caregivers’ names upon patient hospital admission. Most recent available reports from June 2019 indicate that the CARE Act has become law in 42 states22; however, the timeline for implementation of caregiver identification strategies and relevance for outpatient oncology is unclear. Nevertheless, the CARE Act demonstrates national recognition of the importance of documenting caregivers of inpatients.

One strategy advancing aspirations of NCI/NINR’s recommendation to improve caregiver assessment is to incorporate risk stratification strategies to identify highly stressed patients and caregivers. Although our study observed only 40% of practice groups report systematic caregiver identification and documentation practices, surprisingly, 76% of practice groups reported assessing caregivers’ needs. These findings suggest assessment is not occurring systematically, but rather appears to be carried out in an opportunistic manner. Before providing specific recommendations to implement risk stratification processes, more information is needed about current caregiver assessment processes, specific assessment instruments and their validity, and ultimately the impact of assessment efforts. For example, it is possible caregiver needs assessment tools are only being used for caregivers who present for supportive care services or those who proactively seek services. Whereas patient distress screening has been recognized by the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2008) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN, 2018) as a critical component to high quality comprehensive cancer care delivery and consequently has been largely implemented in the oncology healthcare setting as the 6th vital sign, caregiver distress screening has not.23,24 Implementing routine assessment of cancer caregiver needs may support risk stratification processes targeting the most vulnerable caregivers with the greatest needs and distress.7,12,25,26 One recent study supported the feasibility and acceptability of conducting distress screening among caregivers in a surgical oncology setting.27 Our findings suggest community oncology healthcare may have the infrastructure to support routine caregiver assessment, though further information is needed to guide implementation.

Most practice groups (64%) reported that they have at least one type of supportive care service available for caregivers. Although promising, it is not clear if and how caregivers are being connected to these services, especially since only half of practice groups systematically identified caregivers. Indeed, studies demonstrate caregivers have significant unmet needs and sub-optimally utilize supportive care services. 28-31 Additionally, because patients remain the primary focus in oncology care settings, it is not clear what types of funding support caregiver supportive care services, augmenting caregiver care access concerns. Community organizations may provide caregiver services and national-level resources are often available (e.g., American Cancer Society). However, without education about such services and targeted referrals, caregivers shoulder the burden of seeking services in the midst of juggling patient care, work, and other home obligations. One study demonstrated that among a national sample of informal caregivers, 73% accessed online health-related information for themselves, suggesting caregivers take initiative to seek resources, at least online; however, this study was not cancer caregiver-specific.32 Advocates describe cancer caregiving as a particularly intense and episodic experience with a high prevalence of burden,1 ultimately challenging caregivers’ abilities to meet their own needs.

Our results also highlight variability in the types of supportive care services available in the oncology setting with group psychosocial and individual psychosocial/ behavioral services most commonly available and training or education classes infrequently provided. As psychosocial and self-care challenges are highly prevalent in cancer caregivers,1 it is reassuring that the majority of sites provided some type of psychosocial (e.g., coping support, counseling) or behavioral (e.g., smoking cessation, stress management) services for caregivers to address those needs. A critical next step is to assure a more systematic planning approach in oncology care settings to assure available services match caregivers’ needs. In particular, our findings showed that less than a quarter of practice groups offered training or educational services for caregivers. This is consistent with prior findings revealing caregivers report receiving little to no training, and feeling unprepared for their caregiver role.1,3 These findings are concerning because caregivers frequently endorse a need for or interest in training/ educational resources.33-35 The need for caregiver education is likely increasing, as developments in cancer treatment (e.g., oral agents, immunotherapy) may place an even greater demand on caregivers to understand and manage complex treatment regimens at home, with less frequent clinic visits.36,37 Caregiver support strategies can assist those caregivers monitoring their loved ones’ treatment and disease trajectory. Caregivers overseeing patients on oral agents and immunotherapy may particularly benefit from research testing technology-supported interventions to facilitate caregiving (e.g., self-management, remote symptom monitoring, medication adherence tools).

Our analyses showed some variability in caregiver practices by site characteristics. A clear pattern of caregiver practices according to site characteristics was not evident in this study. In some instances, it was counterintuitive. For example, critical access hospitals were more likely to identify/document caregivers and offer supportive services. Critical access hospitals are often under-resourced, thus it is surprising they were more likely to report caregiver engagement practices. These findings could reflect practice groups’ recognition of the critical role cancer caregivers play in facilitating care with vulnerable populations.38-40 However, additional research is warranted to describe the specific ways practices engage and care for caregivers, including the depth and timing of assessment and services, as well as reimbursements amenable to service provision.

Limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting results. First, although NCORP sites include a wide variety of oncology settings across the country, we lack data to compare participating Landscape practices to non-participating practices. Second, NCORP sites may lack generalizability to oncology practices nationwide. Both the NCORP network and this Landscape’s sub-sample contain fewer practice groups from the Northeast than observed nationally. This limited our ability to draw strong conclusions about regional differences. Third, as these questions were embedded in a larger assessment of cancer care delivery capacity among NCORP practices, we could not collect complementary data from patients or caregivers. Additionally, although we solicited information on several types of common supportive care services, we did not exhaust all possible service types. However, our survey included a free text box allowing respondents to document services our questions failed to capture.

Summary

This study focused on characterizing oncology practices in the oncology setting to assess and address needs in cancer caregivers’ and was strengthened by undertaking a nation-wide assessment of community oncology clinics, where most cancer patients receive care.41 This is the first study to collect these type of data, thus serving as a resource for those invested in advancing cancer caregiving research, particularly within the NCORP network. This study also provides baseline data form which to consider any subsequent practice changes.

Though this study provides the first evidence of caregiver identification/ documentation and assessment practices, as well as supportive care services available to caregivers within community oncology practice groups, additional research is needed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of effective strategies to carry out these engagement practices to guide development of feasible interventions to efficiently link caregivers to needed resources. It will also be important to conduct additional research to characterize provider-, clinic- and policy-level factors and their impact on caregiver engagement practices and provider recommendations, willingness, and barriers for engaging with caregivers. Additional research directions include identification of optimal technology modalities to support caregivers in community oncology practices. 7 A more in depth assessment of barriers and facilitators to reaching caregivers, such as those suggested by Northouse et al. 12 (e.g., provider training, cost for services) would provide key information to guide interventions addressing system-, provider-, and caregiver- barriers, and incorporating technology in alignment with previous recommendations.7 Addressing barriers at multiple levels is critical for successful implementation and sustainability of supportive care services in community oncology practices. System-level approaches42 are needed to comprehensively address caregiver needs over time in the dynamic oncology setting. With a better understanding of current strategies for, and barriers to caregiver identification, assessment, and supportive care service availability, we can develop best practices to reach caregivers in diverse oncology treatment settings. 43

Acknowledgments:

We thank the NCORP investigators and staff at NCORP Community and Minority/Underserved Community Sites that participated in the Landscape Assessment data collection.

Funding: This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP), including Awards 1UG1 CA189824 (Wake Forest Health Sciences NCORP Grant), 2UG1 CA189828 (ECOG-ACRIN NCORP Research Base), UCA189972B (NCORP of the Carolinas). Chandylen Nightingale’s work on this manuscript was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), of the NIH (UL1TR001420). Laurie McLouth’s work was supported by the NCI of the NIH (R25CA122061).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Cancer Caregiving ∣ National Alliance for Caregiving. Accessed July 8, 2016 http://www.caregiving.org/cancer/

- 2.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Spillers RL, Evans TV. Needs assessment of family caregivers of cancer survivors: three cohorts comparison. Psychooncology. 2009;19(6):573–582. doi: 10.1002/pon.1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashemi-Ghasemabadi M, Taleghani F, Yousefy A, Kohan S. Transition to the new role of caregiving for families of patients with breast cancer: a qualitative descriptive exploratory study. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(3):1269–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2906-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mollica MA, Litzelman K, Rowland JH, Kent EE. The role of medical/nursing skills training in caregiver confidence and burden: A CanCORS study. Cancer. 2017;123(22):4481–4487. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. Hidden Morbidity in Cancer: Spouse Caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(30):4829–4834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butow PN, Price MA, Bell ML, et al. Caring for women with ovarian cancer in the last year of life: a longitudinal study of caregiver quality of life, distress and unmet needs. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(3):690–697. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–1995. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sörensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(3):356–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent EE, Dionne-Odom JN. Population-Based Profile of Mental Health and Support Service Need Among Family Caregivers of Adults With Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2018;15(2):e122–e131. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammer SL, Clark K, Grant M, Loscalzo MJ. Seventeen years of progress for supportive care services: A resurvey of National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(4):917–925. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ugalde A, Gaskin CJ, Rankin NM, et al. A systematic review of cancer caregiver interventions: Appraising the potential for implementation of evidence into practice. Psychooncology. 2019;28(4):687–701. doi: 10.1002/pon.5018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Northouse L, Williams A-L, Given B, Mccorkle R. Psychosocial Care for Family Caregivers of Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NCORP :: NCI Community Oncology Research Program. Accessed January 27, 2017 https://ncorp.cancer.gov/

- 14.Kent EE, Mitchell SA, Castro KM, et al. Cancer Care Delivery Research: Building the Evidence Base to Support Practice Change in Community Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(24):2705–2711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.6210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cathcart-Rake EJ, Zemla T, Jatoi A, et al. Acquisition of sexual orientation and gender identity data among NCI Community Oncology Research Program practice groups. Cancer. 2019;125(8):1313–1318. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlos RC, Sicks JD, Chang GJ, et al. Capacity for Cancer Care Delivery Research in National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program Community Practices: Availability of Radiology and Primary Care Research Partners. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14(12):1530–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosher CE, Champion VL, Hanna N, et al. Support service use and interest in support services among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2013;22(7):1549–1556. doi: 10.1002/pon.3168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dionne-Odom JN, Applebaum AJ, Ornstein KA, et al. Participation and interest in support services among family caregivers of older adults with cancer. Psychooncology. Published online December 11, 2017. doi: 10.1002/pon.4603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Census.gov. Accessed November 22, 2019 https://census.gov/

- 20.The CARE Act Implementation: Progress and Promise - AARP Spotlight. Accessed March 16, 2020 https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:yQtgX1P2vtcJ:https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/03/the-care-act-implementation-progress-and-promise.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

- 21.The CARE Act: Identifying and Supporting Family Caregivers From Hospitals to Home. Dimens Crit Care Nurs DCCN. 2018;37(2):59–61. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AARP. The Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable (CARE) Act. Published June 2019. Accessed March 16, 2020 https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/09/care-act-map.pdf

- 23.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Published October 5, 2017. Accessed October 5, 2017 https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp

- 24.Ehlers SL, Davis K, Bluethmann SM, et al. Screening for psychosocial distress among patients with cancer: implications for clinical practice, healthcare policy, and dissemination to enhance cancer survivorship. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(2):282–291. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambert SD, Ould Brahim L, Morrison M, et al. Priorities for caregiver research in cancer care: an international Delphi survey of caregivers, clinicians, managers, and researchers. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(3):805–817. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4314-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaffer KM, Benvengo S, Zaleta AK, et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of Distress Screening for Family Caregivers at a Cancer Surgery Center. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2019;46(2):159–169. doi: 10.1188/19.ONF.159-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Applebaum AJ, Farran CJ, Marziliano AM, Pasternak AR, Breitbart W. Preliminary study of themes of meaning and psychosocial service use among informal cancer caregivers. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12(2):139–148. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lichtenthal WG, Nilsson M, Kissane DW, et al. Underutilization of mental health services among bereaved caregivers with prolonged grief disorder. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2011;62(10):1225–1229. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.10.pss6210_1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, et al. When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121(9):1513–1519. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litzelman K, Reblin M, McDowell HE, DuBenske LL. Trajectories of social resource use among informal lung cancer caregivers. Cancer. Published online October 18, 2019. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaffer KM, Chow PI, Cohn WF, Ingersoll KS, Ritterband LM. Informal Caregivers’ Use of Internet-Based Health Resources: An Analysis of the Health Information National Trends Survey. JMIR Aging. 2018;1(2):e11051. doi: 10.2196/11051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nightingale CL, Sterba KR, Tooze JA, et al. Vulnerable characteristics and interest in wellness programs among head and neck cancer caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3437–3445. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3160-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nightingale CL, Steffen LE, Tooze JA, et al. Lung Cancer Patient and Caregiver Health Vulnerabilities and Interest in Health Promotion Interventions: An Exploratory Study. Glob Adv Health Med. 2019;8:2164956119865160–2164956119865160. doi: 10.1177/2164956119865160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Longacre ML. Cancer caregivers information needs and resource preferences. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):297–305. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0472-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall VK, Cairns PL. Challenges of Caregivers of Cancer Patients who are on Oral Oncolytic Therapy. Caregiving Pers Cancer. 2019;35(4):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudnitzki T, McMahon D. Oral agents for cancer: safety challenges and recommendations. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:41–46. doi:doi: 10.1188/15.S1.CJON.41-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Distel E, Casey M, Prasad S. Reducing Potentially-Preventable Readmissions in Critical Access Hospitals.; 2016.

- 39.Casillas A, Cemballi AG, Abhat A, et al. An Untapped Potential in Primary Care: Semi-Structured Interviews with Clinicians on How Patient Portals Will Work for Caregivers in the Safety Net. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(7):e18466. doi: 10.2196/18466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: a meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):823–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfister DG, Rubin DM, Elkin EB, et al. Risk Adjusting Survival Outcomes in Hospitals That Treat Patients With Cancer Without Information on Cancer Stage. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(9):1303–1310. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quillin JM, Tracy K, Ancker JS, et al. Health care system approaches for cancer patient communication. J Health Commun. 2009;14 Suppl 1:85–94. doi: 10.1080/10810730902806810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Northouse L, Williams A -l., Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial Care for Family Caregivers of Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]