Abstract

Objective:

Our study examines how consistently fall prevention practices and implementation strategies are used by U.S. hospitals.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional, descriptive study of 60 general adult hospital units.

We administered a survey measuring 5 domains of fall prevention practices: visibility and identification, bed modification, patient monitoring, patient safety, and education. We measured 4 domains of implementation strategies including quality management (e.g., providing data and support for quality improvement), planning (e.g., designating leadership), education (e.g., providing consultation and training), and restructuring (e.g., revising staff roles and modifying equipment).

Results:

Of 60 units, 43% were medical units and 57% were medical-surgical units. The hospital units varied in fall prevention practices, with practices such as keeping a patient’s bed in a locked position (73% strongly agree) being used more consistently than other practices, such as scheduled toileting (15% strongly agree). Our study observed variation in fall prevention implementation strategies. For example, publicly posting fall rates (60% strongly agree) was more consistently used than having a multidisciplinary huddle after a fall event (12% strongly agree).

Conclusions:

There is substantial variation in the implementation of fall prevention practices and implementation strategies across inpatient units. Our study found that resource-intensive practices (e.g., scheduled toileting) are less consistently used than less resource-intensive practices and that interdisciplinary approaches to fall prevention are limited. Future studies should examine how units tailor fall prevention practices based on patient risk factors and how units decide, based on their available resources, which implementation strategies should be used.

Keywords: fall prevention, implementation strategies, hospital falls

Hospital falls are a problem worldwide and threaten patient safety, particularly among geriatric patients.1 Geriatric patients are more likely to fall and sustain a fall-related injury.2–4 In the United States, estimated hospital fall rates vary from 3.3 to 11.5 falls per 1000 patient days.3,5–9 Approximately 25% of hospital falls result in injury, increasing a patient’s length of stay, healthcare costs, and liability.9–13 In addition, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will not reimburse hospitals for care when patients experience certain fall-related injuries, creating significant financial pressure for hospitals to prevent falls.14 Unlike other healthcare acquired conditions, there are no agreed-upon, evidence-based interventions for fall prevention,15–23 making it difficult for hospitals to discern which prevention practices have the biggest impact on fall rates.

There are a wide array of fall prevention practices that hospitals can implement, such as patient monitoring tools (e.g., sitters), modifications to a patient’s bed (e.g., alarms), identification practices (e.g., bracelets), safety practices (e.g., clutter free floors), and patient and family education. The evidence for implementing any one of these practices is weak15–21 and, in some cases, negative.24,25 Bed alarms, for example, have been found to be ineffective in preventing falls and harmful (e.g., noise, alarm fatigue) but are still routinely used in hospital settings.18,24,26–28 There is stronger evidence for using multicomponent interventions; however, it is unclear which components yield the greatest impact on falls.2,16,17,19,22,23,29,30 Experts recommend using multicomponent interventions for hospital fall prevention and tailoring the practices based on the unit’s patient population.31 Studies have shown that units vary, however, in the fall prevention practices selected, even when the patient population is similar.32 There is also variability in how fall prevention practices are implemented.17,18,32,33

Hospitals use implementation strategies—methods to promote the implementation of an intervention—to support fall prevention, but these strategies are often under-reported.34,35 In a recent systematic review of hospital, fall prevention interventions reported that only 17% of studies documented implementation strategies.18 Among studies that reported implementation strategies, hospitals most commonly reported using staff education (49%) and quality management strategies (34%), such as posting fall rates or having staff huddles after a fall event.18 However, many of the studies had the primary aim of evaluating the effectiveness of fall prevention practices and did not comprehensively document implementation. Previous research also suggests that lack of consistency in fall prevention implementation may explain null findings of fall prevention interventions.18,36–39 Few studies, however, report data on implementation consistency.18 Furthermore, many of these earlier studies were conducted within a single healthcare organization, which does not provide a comprehensive picture of what hospitals are doing nationally to prevent falls. Additional research is needed to understand what implementation strategies and practices units with similar patient populations use to prevent falls and how consistently the strategies and practices are applied.

To address this gap in the literature, our study examines how consistently fall prevention practices and implementation strategies are used by U.S. general adult hospital units. By better understanding variation in fall prevention practices and implementation, this research will contribute the development of future hospital fall prevention interventions.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional, descriptive study to examine the consistency of fall prevention practices and implementation strategies among general adult hospital units in 2017. The general adult hospital unit was the unit of analysis.

Sample and Setting

The sample was selected from U.S. hospitals participating in the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI). The NDNQI is a national database, owned by Press Ganey, which collects and reports unit level nursing-sensitive indicators. The study included adult medical and medical/surgical units that submitted falls data for the first and second quarter of 2017. To ensure comparability across hospitals, units classified in the sample as medical or medical-surgical have 90% or more patients receiving general care, according to the NDNQI unit type definitions. The study excluded units within federally owned hospitals. Our target sample for this initial descriptive study was 80 units. Press Ganey sent invitations to eligible hospitals (n = 700). One hundred eighty-nine hospitals indicated interest in participating in the first 24 hours. We randomly selected 80 of these initial responders. The sampling strategy was designed to include 20 hospitals in 4 strata based on hospital size (<200 beds, ≥200 beds) and teaching status (yes/no). Among the 80 hospitals selected, 60 nurse managers completed the survey (74% response rate).

Data Collection and Measures

We used a 3-phase approach to develop a survey assessing general adult hospital units’ fall prevention practices and implementation strategies. First, we reviewed the literature and expert panel guidelines to identify fall prevention practices and implementation strategies.31,40–42 Second, the survey was reviewed by 10 fall prevention experts (e.g., geriatricians and advanced practice registered nurses in acute care) to assess face validity and review item clarity. Third, the survey was pilot tested at 3 sites and further refined for clarity and ease of completion. The final survey contained 55 items and covered 5 domains of fall prevention practices: visibility and identification, bed modification, patient monitoring, patient safety, and education. These practices were selected to cover a wide range of commonly endorsed fall prevention practices.17,31 The survey also covered 4 domains of implementation strategies including quality management (e.g., providing data and support for quality improvement), planning (e.g., designating leadership), education (e.g., providing consultation and training), and restructuring (e.g., revising staff roles and modifying equipment). These strategies were selected from the ERIC categorization of implementation strategies.34,43

In addition, we obtained hospital-level characteristics (e.g., teaching status, size, ownership, Magnet status, rural or urban location) and unit-level characteristics (type, unit bed size, number of patients) from the NDNQI. Measure definitions are provided hereinafter.

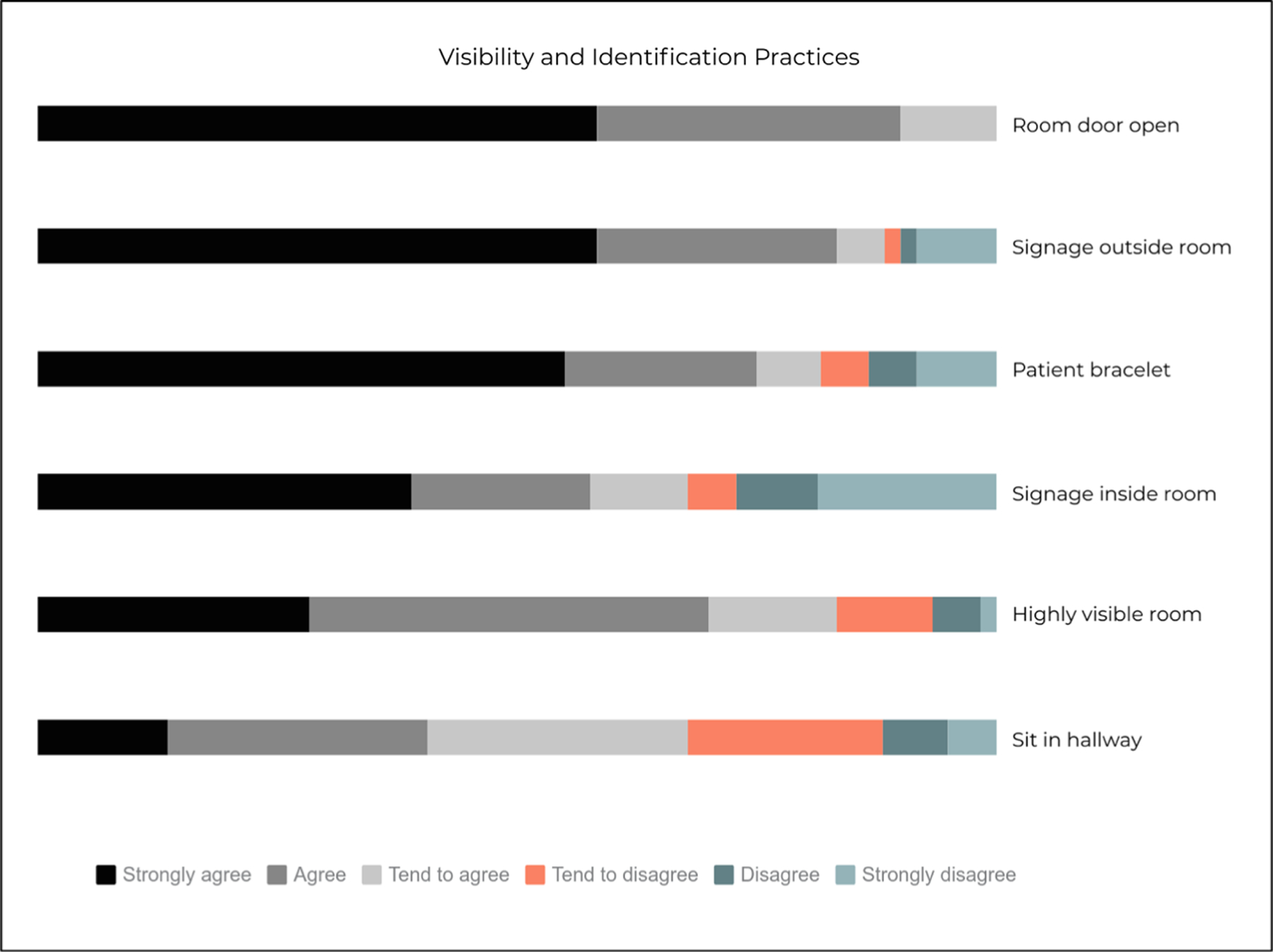

Visibility and identification fall prevention practices were measured using 6 Likert scales. The response options were on a 6-point scale that ranged from strongly agree, agree, tend to agree, tend to disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree. The Likert scales measured unit managers’ level of agreement regarding the extent to which the following practices were used consistently in their unit: keeping a patient’s room door open, having signage outside the room, having the patient wear a fall risk bracelet, having signage inside the room, placing the patient in a highly visible room, and allowing patients to sit in the hallway.

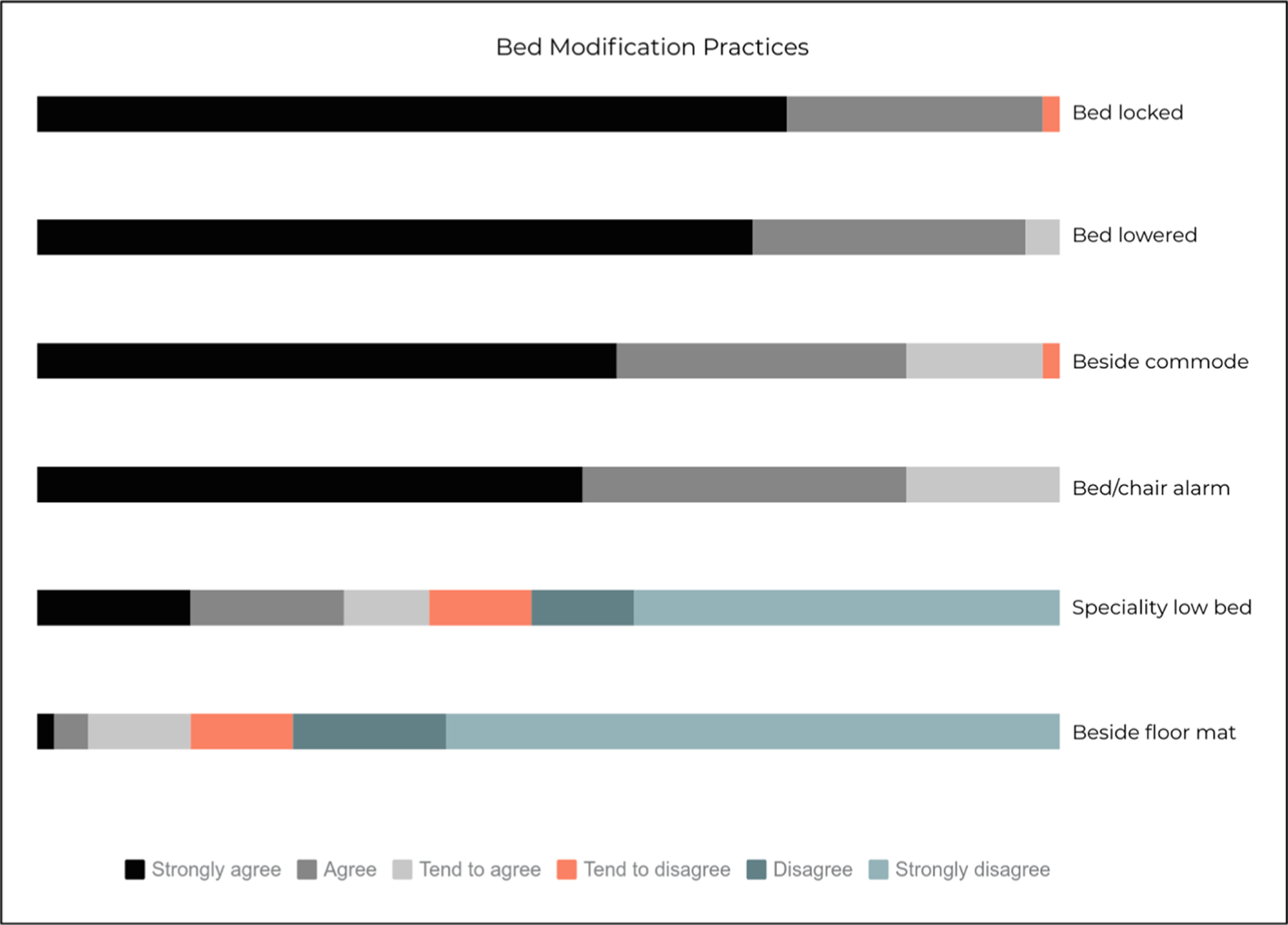

Bed modification practices were measured using 6 Likert scales assessing unit nurse managers’ level of agreement regarding the extent to which the following practices were used consistently in their unit: having the bed locked in place, having the bed lowered, having a bedside commode, using a bed or chair alarm, using a specialty low bed, and using a bedside floor mat.

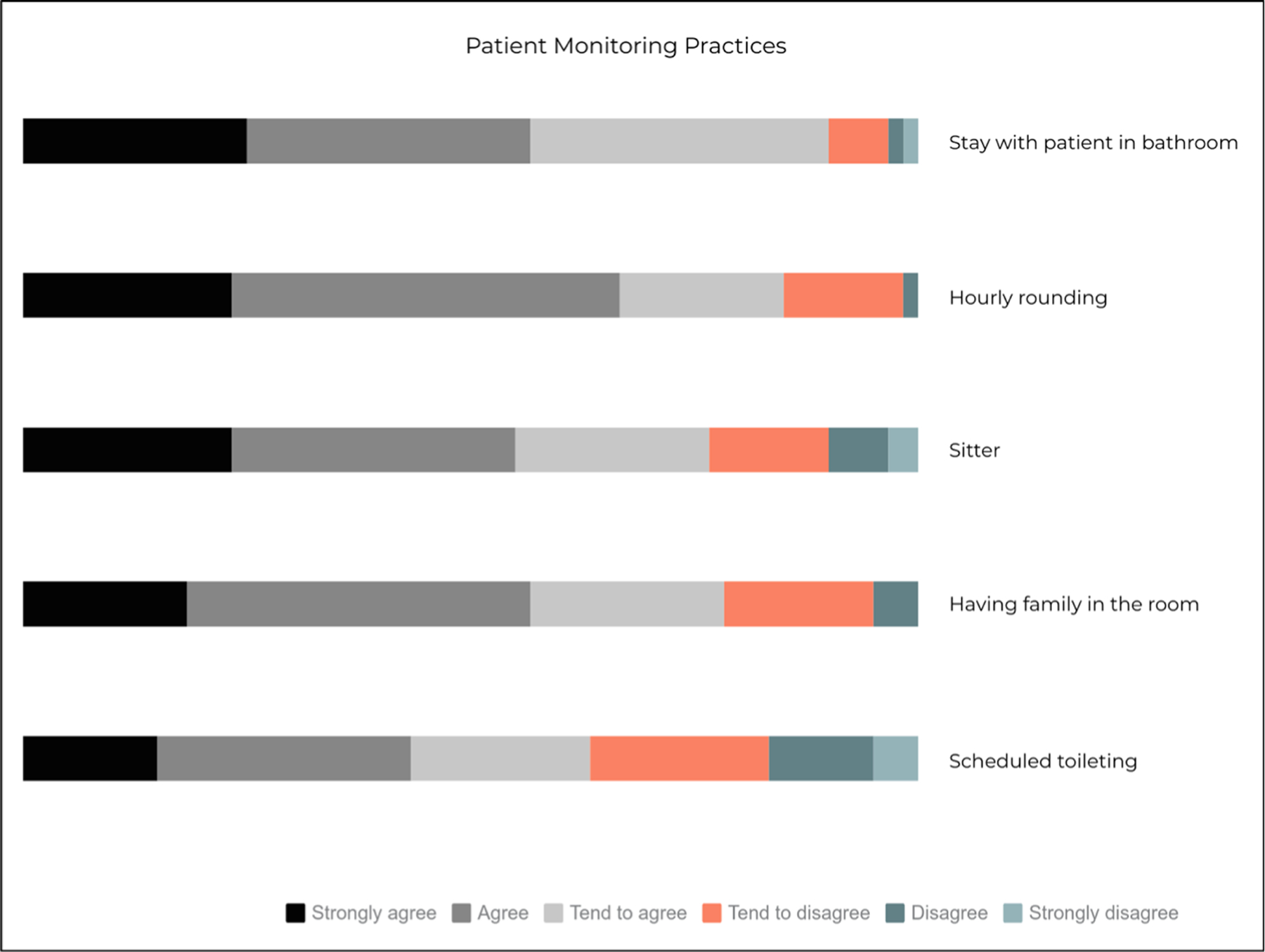

Patient monitoring practices were measured using 5 Likert scales assessing unit nurse managers’ level of agreement regarding the extent to which the following practices were used consistently in their unit: staying with patients in the bathroom, hourly rounding, having sitters for high-risk patients, having family in the room, and scheduled toileting.

Patient safety practices were measured using 4 Likert scales assessing unit nurse managers’ level of agreement regarding the extent to which the following practices were used consistently in their unit: giving patients nonskid socks, having the call light accessible, having a clutter free floor, and making an ambulatory aid accessible.

Education practices were measured using 2 Likert scales assessing unit nurse managers’ level of agreement regarding the extent to which the following practices were used consistently in their unit: educating patients on fall prevention and educating families on fall prevention.

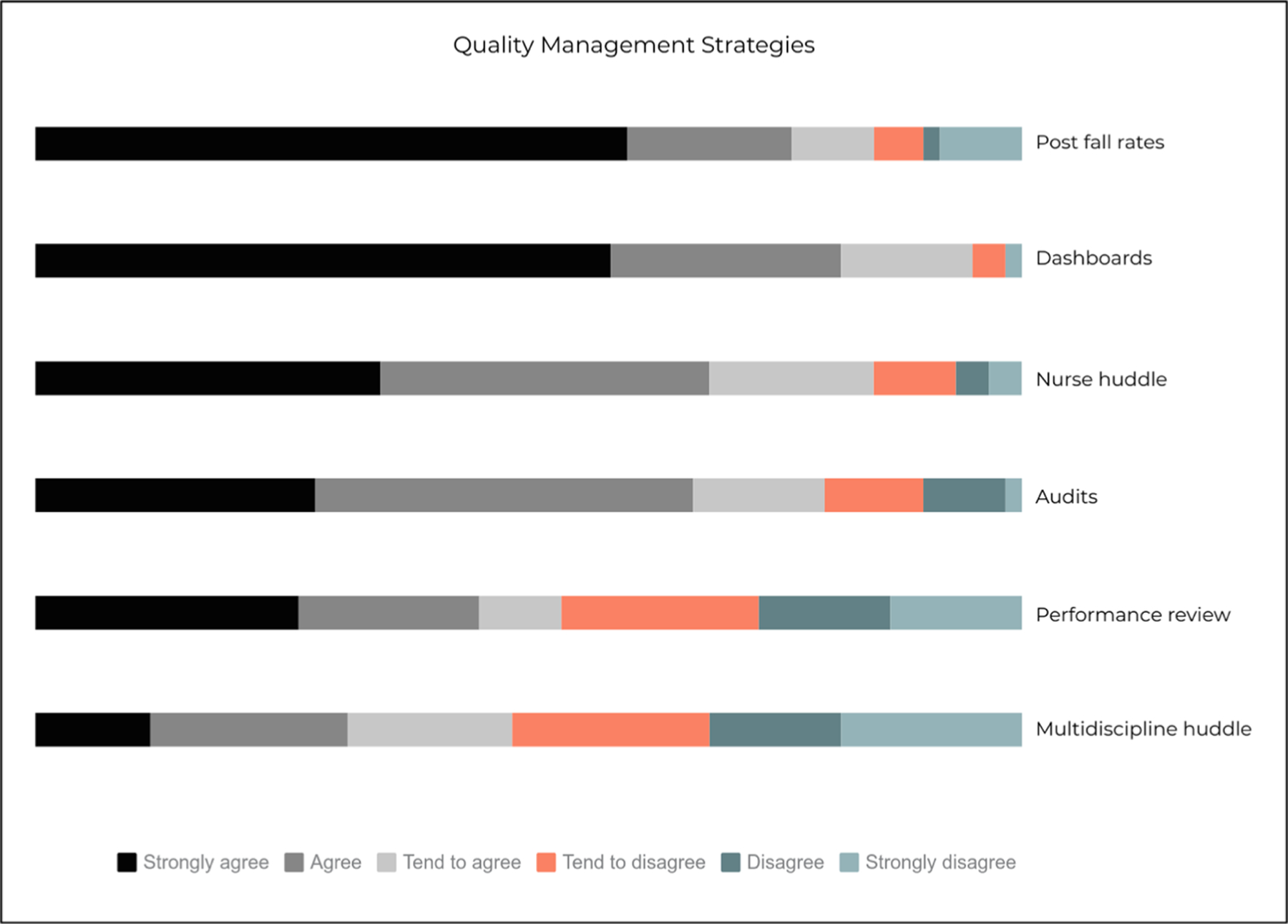

Quality management implementation strategies were measured using 6 Likert scales assessing unit nurse managers’ level of agreement regarding the extent to which the following strategies were used consistently in their unit: posting fall rates, using dashboards, having a postfall huddle among nurses, having a post fall huddle among a multidisciplinary team, post fall audits, and incorporating fall rates into performance reviews.

Planning strategies included whether the unit had a nurse fall prevention champion, a physician leader of fall prevention quality initiatives, and, if a nurse from the unit serves on the hospital-level, fall prevention committee. These items were measured as binary variables because the items measure the presence or absence of a strategy.

Education strategies were measured using a Likert scale assessing unit nurse managers’ level of agreement regarding the extent to which units educate newly hired nurses on fall prevention. In addition, education implementation strategies included whether the unit had access to consultation services from palliative care, psychiatry, geriatrics, or an advanced practice nurse (binary variables). Education implementation strategies also included access to interdisciplinary resources including case managers, social workers, clinical pharmacists, dieticians, physical therapists, quality management specialists, occupational therapists, respiratory therapists, and speech therapists. The interdisciplinary resources variables were categorized based on whether the resource was assigned to the unit, a rotating member of the unit, or not available on the unit.

Restructuring strategies were measured using 4 Likert scales assessing unit nurse managers’ level of agreement about availability of additional staffing and equipment. Availability of additional staffing included how easy it is within the unit to find replacements for nursing personnel who called off for the next work shift and how easy it is to obtain sitters for high-risk fall patients. Availability of equipment included how easy it is to find working bed and chair alarms, specialty low beds, and safety lift and transfer devices for every patient on the unit.

Data Collection Procedure

Press Ganey administered an online survey and sent out 2 reminder e-mails. Every hospital had a designated NDNQI representative responsible for collecting the data and completing the survey. The institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Kansas Medical Center approved the study and hospitals could either accept the University of Kansas Medical Center IRB or apply for their own IRB approval before data collection. Data were collected from October 1, 2017, to December 31, 2017.

Data Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics, using percentages for categorical variables and the median and interquartile range for count variables. The amount of missing data was minimal (4.4%), so we used complete case analysis to handle missing data. The analyses were conducted using Stata Version 13.0 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Of 60 units, 43% were medical and 57% were medical-surgical units (Table 1). Units had a median bed size of 31 (interquartile range [IQR] = 24–36). The median number of patients on the unit was 24 (IQR = 20–30). Most units were located in not-for-profit (98%) and urban hospitals (90%). The sample had an even mix of Magnet designation (53%), small (53%), and teaching (52%) hospitals.

TABLE 1.

Sample Characteristics

| All Units (N = 60) | |

|---|---|

| Unit-level characteristics | |

| Unit type, % | |

| Medical | 43.3 |

| Medical-surgical | 56.7 |

| Unit bed size, median (IQR) | 31 (24–36) |

| No. patients, median (IQR) | 24 (20–30) |

| Hospital-level characteristics | |

| Hospital ownership, % | |

| Not-for-profit | 98.3 |

| For-profit | 1.7 |

| Urban hospital, % | 90.0 |

| Magnet hospital, % | 53.3 |

| Small hospital (<200 beds), % | 53.3 |

| Teaching hospital, % | 51.7 |

Fall Prevention Practices

For visibility and identification practices, unit managers were most likely to strongly agree (58%) or agree (32%) that nursing staff consistently keep patients’ room doors open and place signage outside the patients’ rooms (58% strongly agree, 25% agree; Fig. 1 and Supplemental File 1, http://links.lww.com/JPS/A340). Other consistently used practices included having patients wear a fall-risk bracelet (39% strongly agree, 20% agree) and placing at-risk patients in a highly visible room (28% strongly agree, 42% agree). Giving patients the ability to sit in the hallway was the least consistently used practice (14% strongly agree, 27% agree).

FIGURE 1.

Visibility and identification practices (n = 59).

For bed modification practices, unit managers were most likely to strongly agree (73%) or agree (25%) that units keep patient beds in the locked and lowered position (70% strongly agree, 27% agree; Fig. 2 and Supplemental File 1, http://links.lww.com/JPS/A340). Other consistently used practices included having a bedside commode (57% strongly agree, 28% agree) and having a bed or chair alarm (53% strongly agree, 32% agree). Using a specialty low bed (15% strongly agree, 15% agree) and having a bedside floor mat (2% strongly agree, 3% agree) were the least consistently used practices.

FIGURE 2.

Bed modification practices (n = 60).

For patient monitoring practices, unit managers were most likely to strongly agree (25%) or agree (32%) that staff stay with patients in bathroom, complete hourly rounding (23% strongly agree, 43% agree), or use sitters (23% strongly agree, 32% agree; Fig. 3 and Supplemental File 1, http://links.lww.com/JPS/A340). Having family in the room (18% strongly agree, 38% agree) or having scheduled toileting (15% strongly agree, 28% agree) were the least consistently used practices.

FIGURE 3.

Patient monitoring practices (n = 60).

For patient safety practices, unit managers were most likely to strongly agree (72%) or agree (25%) that units provided nonskid socks to patients or an accessible call light (58% strongly agree, 35% agree; Supplemental File 1, http://links.lww.com/JPS/A340). Units also consistently maintained a clutter-free floor (30% strongly agree, 50% agree) and provided an accessible ambulatory aid (27% strongly agree, 37% agree).

For education practices, units consistently educated patients on fall prevention (43% strongly agree, 38% agree) and families (30% strongly agree, 40% agree; Supplemental File 1, http://links.lww.com/JPS/A340).

Fall Prevention Implementation Strategies

For quality management implementation strategies, unit managers were most likely to strongly agree (60%) or agree (17%) that units posted fall rates or used dashboards to display fall rates (58% strongly agree, 23% agree; Fig. 4). Units consistently performed nurse huddles (35% strongly agree, 33% agree) and audits of fall rates (28% strongly agree, 38% agree). Including fall rates in performance reviews (27% strongly agree, 18% agree) and using multidisciplinary huddles (12% strongly agree, 20% agree) were the least consistently used strategies.

FIGURE 4.

Quality management strategies (n = 60).

For planning implementation strategies, approximately half of units reported designating a nurse as a fall champion (49%) or having a nurse from the unit serve on the hospital falls committee (47%; Supplemental File 2, http://links.lww.com/JPS/A340). Units less commonly reported designating a physician to serve as a leader of falls improvement initiatives (22%).

For education implementation strategies, most units reported having access (i.e., yes) to consultation from palliative care specialists (93%) or reported having access to consultation from psychiatry specialists (85%) for falls prevention. Less than half of units reported access to consultation from geriatric specialists (43%) or an advanced practice nurse (27%). Most unit representatives strongly agreed (59%) or agreed (24%) that newly hired nurses were required to receive education on falls prevention.

Units varied in access to interdisciplinary resources. Most units had a case manager (82%) and social worker (78%) assigned to the unit (Table 2). Units were less likely to have clinical pharmacists (37%), dieticians (35%), physical therapists (28%), quality management specialists (22%), occupational therapists (22%), respiratory therapists (22%), or speech therapists (13%) assigned to the unit.

TABLE 2.

Access to Interdisciplinary Resources for Fall Prevention (n = 59)

| Interdisciplinary Resource | Assigned to the Unit | Rotating Member of the Unit | Not Available on the Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case manager | 83.1 | 17.0 | 0.0 |

| Social worker | 79.7 | 18.6 | 1.7 |

| Clinical pharmacist | 37.3 | 56.0 | 6.8 |

| Dietician | 35.6 | 62.7 | 1.7 |

| Physical therapists | 28.8 | 71.2 | 0.0 |

| Quality management specialists | 22.4 | 39.7 | 37.9 |

| Occupational therapists | 22.0 | 71.2 | 6.8 |

| Respiratory therapists | 22.0 | 78.0 | 0.0 |

| Speech therapists | 13.6 | 83.1 | 3.4 |

For restructuring implementation strategies, approximately third of representatives strongly agreed (8%) or agreed (22%) that it is easy to find replacements for nursing personnel who called off for the next shift (Supplemental File 1, http://links.lww.com/JPS/A340). Similarly, approximately 1 in 5 representatives strongly agreed (7%) or agreed (13%) that it is easy to find sitters for high-risk patients. Nearly all representatives strongly agreed (72%) or agreed (22%) that bed and chair alarms are easily available for every patient on the unit. Most representatives also strongly agreed (62%) or agreed (18%) that safety lift and transfer devices were readily available on the unit. Unit representatives were less likely to strongly agree (27%) or agree (5%) that specialty low beds were easily available on the unit.

DISCUSSION

The goal of our study was to examine how consistently fall prevention practices are used by U.S. general adult hospital units and how they are implemented. Our study found that units with similar patient populations still vary in their use of fall prevention practices, with some practices such as keeping a patient’s bed in a locked position (73% strongly agree) being used more consistently than other practices, such as scheduled toileting (15% strongly agree). Similarly, our study observed variation in fall prevention implementation strategies. For example, publicly posting fall rates (60% strongly agree) was more consistently used than having a multidisciplinary huddle after a fall event (12% strongly agree). We also observed that units varied in access to resources, such as consultation from specialists. We discuss implications for practice and future research below.

Consistent with previous studies, we found that general adult hospital units consistently use fall prevention practices that are considered of low value, such as bed and chair alarms (53% strongly agree), although organizations such as the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research and Quality and Joint Commission have cited concerns about the overreliance of bed and chair alarms as a hospital fall prevention strategy.23,28,31,40 in addition, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid recently restricted the use of bed and chair alarms in long-term care facilities citing concerns, such as decreased mobility and sleep disturbances among patients.44 Despite guidance and regulations, a recent study found that healthcare providers report bed and chairs alarms as a highly effective strategy for fall prevention.33 Therefore, additional guidance may be needed that identifies the current level of evidence for available fall prevention practices.

We also observed that time-intensive interventions, such as sitters, scheduled toileting, and hourly rounding, were less consistently used than other fall prevention practices. This is in contrast to a prior study that found that hourly rounding (70%) and sitters (68%) were the most common fall prevention practices.32 It is possible that the difference is due to item wording; the prior study assessed whether a practice was used (e.g., yes/no) and our study assessed nurse managers’ perceptions about whether a practice was consistently used by nursing personnel. Prior studies have reported substantial implementation barriers for patient-monitoring practices, such as increased workload, competing priorities, lack of staff buy-in, and cost.45–50 For example, one study reported that a sitter intervention increased cost by more than US $1 million annually.48 Despite recommendations for these practices, few of these practices have been evaluated rigorously through a randomized design or have been evaluated for cost-effectiveness.25,45 Future studies should test patient monitoring fall prevention practices using randomized designs with a cost-effectiveness evaluation.

Our study found that fall prevention was implemented in diverse ways. Quality management strategies aimed at increasing awareness of fall rates (e.g., posting fall rates, using dashboards) were used more consistently than strategies to provide feedback to healthcare providers (e.g., audits and performance reviews). A prior study reported similar results—15% of nurses reported that fall prevention was included in their annual reviews.32 Including safety practices in performance reviews and auditing and delivering feedback to healthcare providers can be an effective implementation strategy for provider behavior change.51 Future studies should test the effectiveness of strategies, such as audit and feedback, for fall prevention and determine the ideal conditions for implementation.

Our study also found variation in units’ implementation strategies for educating staff on fall prevention and restructuring resources to support fall prevention efforts. For example, a small percentage of participants strongly agreed (8%) that it was easy to find personnel replacements for nursing staff who called off for the next shift, suggesting that some units may not have sufficient staffing. Prior studies suggest that adequate staffing can affect implementation of fall prevention practices and ultimately fall rates.52 Our study also found that many units did not have access to consultations from specialists for falls prevention; less than half of units had access to geriatric specialists (43%) or advance practice nurses (27%). Future studies should explore whether restructuring strategies (e.g., adequate staffing) and education strategies (e.g., access to fall prevention consultation) reduce fall rates.

Limitations

Our study had a few limitations. First, our study sought to describe how consistently fall prevention practices and implementation strategies are used and did not capture the quality with which these practices and strategies are implemented. For example, a unit may use postfall huddles consistently but if the unit does have an effective process for information sharing, the postfall huddles may fail to reduce fall rates. Prior studies suggest that evaluation of implementation quality regarding fall prevention practices is limited.18,21 Therefore, additional research is needed to examine the implementation quality of hospital fall prevention practices. Another limitation is that our study sought to identify the various practices and strategies used by inpatient units, and as a result, it was beyond the scope of the study to explore in depth how each strategy is used. Further studies should explore how units select prevention practices and implementation strategies based on patient risk and local context (e.g., available staffing, available resources). In addition, our study assessed the perceptions of nurse managers rather than nurses who provide direct patient care. We chose to sample nurse managers to obtain perspectives about unit-wide fall prevention practices and strategies, an approach used in other hospital fall studies32,53; however, nurse manager perceptions may differ from frontline nursing staff. Future studies should evaluate the degree of concordance between nurse manager (leader) and frontline nursing staff perceptions about fall prevention practices. Furthermore, although the survey was reviewed for face validity and pilot tested, we did not assess other psychometric properties, such as convergent and discriminant validity. Further work is needed to conduct psychometric testing of these measures. Finally, this was an exploratory study with a small sample (n = 60 units) that was not representative of certain hospital types (e.g., rural hospitals). Larger and more representative studies are needed to see whether the findings in this study are replicated in a larger and more diverse sample of hospitals.

CONCLUSIONS

Preventing hospital falls is an important priority for patient safety, particularly for geriatric patients. There is substantial variation in the implementation of fall prevention practices and implementation strategies across inpatient units. Future studies should examine how units tailor fall prevention practices based on patient risk factors and how units decide, based on their available resources, which implementation strategies should be used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R56 1R56AG051799-01).

Footnotes

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

The funder did not play a role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. 2007. Available at: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WHo-Global-report-on-falls-prevention-in-older-age.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- 2.Oliver D, Healey F, Haines TP. Preventing falls and fall-related injuries in hospitals. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26:645–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krauss MJ, Nguyen SL, Dunagan WC, et al. Circumstances of patient falls and injuries in 9 hospitals in a midwestern healthcare system. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lakatos BE, Capasso V, Mitchell MT, et al. Falls in the general hospital: association with delirium, advanced age, and specific surgical procedures. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hitcho EB, Krauss MJ, Birge S, et al. Characteristics and circumstances of falls in a hospital setting: a prospective analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19:732–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer ID, Krauss MJ, Dunagan WC, et al. Patterns and predictors of inpatient falls and fall-related injuries in a large academic hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:822–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quigley PA, Hahm B, Collazo S, et al. Reducing serious injury from falls in two veterans’ hospital medical-surgical units. J Nurs Care Qual. 2009; 24:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chelly JE, Conroy L, Miller G, et al. Risk factors and injury associated with falls in elderly hospitalized patients in a community hospital. J Patient Saf. 2008;4:178–183. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouldin EL, Andresen EM, Dunton NE, et al. Falls among adult patients hospitalized in the United States: prevalence and trends. J Patient Saf. 2013;9:13–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR. The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:141–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates DW, Pruess K, Souney P, et al. Serious falls in hospitalized patients: correlates and resource utilization. Am J Med. 1995;99:137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brand CA, Sundararajan V. A 10-year cohort study of the burden and risk of in-hospital falls and fractures using routinely collected hospital data. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong CA, Recktenwald AJ, Jones ML, et al. The cost of serious fall-related injuries at three Midwestern hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011; 37:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HHS. Proposed Changes to the Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems and Fiscal Year 2008 Rates. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haines TP, Bennell KL, Osborne RH, et al. Effectiveness of targeted falls prevention programme in subacute hospital setting: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328:676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coussement J, De Paepe L, Schwendimann R, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in acute- and chronic-care hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Ganz DA, et al. Inpatient fall prevention programs as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hempel S, Newberry S, Wang Z, et al. Hospital fall prevention: a systematic review of implementation, components, adherence, and effectiveness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:483–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver D, Connelly JB, Victor CR, et al. Strategies to prevent falls and fractures in hospitals and care homes and effect of cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2007;334:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliver D, Daly F, Martin FC, et al. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital in-patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2004;33:122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliver D, Hopper A, Seed P. Do hospital fall prevention programs work? A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1679–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiBardino D, Cohen ER, Didwania A. Meta-analysis: multidisciplinary fall prevention strategies in the acute care inpatient population. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cameron ID, Dyer SM, Panagoda CE, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9:CD005465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shorr RI, Chandler AM, Mion LC, et al. Effects of an intervention to increase bed alarm use to prevent falls in hospitalized patients: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:692–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeLaurin JH, Shorr RI. Preventing falls in hospitalized patients: state of the science. Clin Geriatr Med. 2019;35:273–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoen MW, Cull S, Buckhold FR. False bed alarms: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:741–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sendelbach S, Funk M. Alarm fatigue: a patient safety concern. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2013;24:378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shivers JP, Mackowiak L, Anhalt H, et al. “Turn it off!”: diabetes device alarm fatigue considerations for the present and the future. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:789–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley A, et al. Fall prevention in acute care hospitals: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1912–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill AM, McPhail SM, Waldron N, et al. Fall rates in hospital rehabilitation units after individualised patient and staff education programmes: a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2592–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.AHRQ. Fall prevention toolkit. 2008; Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/hospital/fallpxtoolkit/index.html. Accessed September 19, 2019.

- 32.Shever LL, Titler MG, Mackin ML, et al. Fall prevention practices in adult medical-surgical nursing units described by nurse managers. West J Nurs Res. 2011;33:385–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tzeng HM, Yin CY. Perceived top 10 highly effective interventions to prevent adult inpatient fall injuries by specialty area: a multihospital nurse survey. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;28:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powell WW, DiMaggio PJ. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The Joint Commission. Preventing falls and fall-related injuries in health care facilities. Sentinel Event Alert. 2015;1–5. [PubMed]

- 37.Nelson E, Reynolds P. Inpatient falls: improving assessment, documentation, and management. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015; 4:u208575.w3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendriks MR, Bleijlevens MH, van Haastregt JC, et al. Lack of effectiveness of a multidisciplinary fall-prevention program in elderly people at risk: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56: 1390–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krauss MJ, Tutlam N, Costantinou E, et al. Intervention to prevent falls on the medical service in a teaching hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Commission J. National patient safety goals. 2018. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/NPSG_Chapter_CAH_Jan2018.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2019.

- 41.Boushon B, Nielsen G, Quigley P, et al. Transforming Care at the Bedside How-to Guide: Reducing Patient Injuries From Falls. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tzeng HM, Yin CY. Patient engagement in hospital fall prevention. Nurs Econ. 2015;33:326–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69:123–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.CMS. Frequently asked questions related to long term care: regulations, survey process, and training. 2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/GuidanceforLawsAndRegulations/Downloads/LTC-Survey-FAQs.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- 45.Christiansen A, Coventry L, Graham R, et al. Intentional rounding in acute adult healthcare settings: a systematic mixed-method review. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(9–10):1759–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toole N, Meluskey T, Hall N. A systematic review: barriers to hourly rounding. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24:283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deitrick LM, Baker K, Paxton H, et al. Hourly rounding: challenges with implementation of an evidence-based process. J Nurs Care Qual. 2012; 27:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spiva L, Feiner T, Jones D, et al. An evaluation of a sitter reduction program intervention. J Nurs Care Qual. 2012;27:341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salamon L, Lennon M. Decreasing companion usage without negatively affecting patient outcomes: a performance improvement project. Medsurg Nurs. 2003;12:230–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryan L, Jackson D, Woods C, et al. Intentional rounding - an integrative literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:1151–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He J, Staggs VS, Bergquist-Beringer S, et al. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes: a longitudinal study on trend and seasonality. BMC Nurs. 2016;15:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Effken JA, Verran JA, Logue MD, et al. Nurse managers’ decisions: fast and favoring remediation. J Nurs Adm. 2010;40:188–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.