Abstract

While the “Undetectable=Untransmittable” (U=U) message is widely endorsed, little is known about its breadth and reach. Our study describes socio-demographic characteristics and sexual behaviors associated with having heard of and trusting in U=U in a U.S. national sample of HIV-negative participants. Data were derived from the Together 5,000 cohort study, an internet-based U.S. national cohort of cis men, trans men and trans women who have sex with men. Approximately 6 months after enrollment, participants completed an optional survey included in the present cross-sectional analysis (n = 3286). Measures included socio-demographic and healthcare-related characteristics; questions pertaining to knowledge of and trust in U=U (dependable variable). We used descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic models to identify characteristics associated with these variables and explored patterns in willingness to engage in condomless anal sex (CAS) with regard to trust in U=U. In total, 85.5% of participants reported having heard of U=U. Among those aware of U=U, 42.3% indicated they trusted it, 19.8% did not, and 38.0% were unsure about it. Latinx, Asian, lower income, and Southern participants were less likely to have heard of U=U. Having had a recent clinical discussion about PrEP or being a former-PrEP user were associated with trust in U=U. Willingness to engage in CAS was positively associated with trust in U=U, and varied based on the partner’s serostatus, PrEP use and viral load. Although we found high rates of awareness and low levels of distrust, our study indicated that key communities remain unaware and/or skeptical of U=U.

Keywords: Undetectable, Viral suppression, U=U, People living with HIV, Biomedical prevention

Resumen

Mientras que el mensaje de “Indetectable=Intransmisible” (I=I) es ampliamente respaldado, poco se conoce acerca de su alcance y amplitud. Nuestro estudio describe características sociodemográficas y los comportamientos sexuales asociados con haber escuchado de y confiar en I=I en una muestra nacional Estadounidense de participantes VIH-negativos. Los datos se derivaron de Together 5,000, un estudio cohorte en donde se recopiló datos de un cohorte basado en internet de hombres cis, hombres trans y mujeres trans que tienen sexo con otros hombres. Aproximadamente 6 meses después de la inscripción, los participantes completaron una encuesta opcional cuyos datos son presentados en este análisis transversal (n = 3286). Los instrumentos incluyeron características socio-demografías y relacionadas al cuidado de la salud; preguntas pertinentes al conocimiento de y confianza en I=I (variable dependiente). Usamos estadísticas descriptivas y modelos logísticos multivariables para identificar características asociadas a estas variables y exploramos los patrones en la disposición a participar de sexo anal sin condones (CAS) con respecto a la confianza en I=I. En total, 85.5% de los participantes reportaron haber escuchado de I=I. Entre esos, 42.3% indicó que confiaban en el mensaje, 19.8% no confiaban, y 38.0% estaban inseguros. Los participantes latinx, asiáticos, de bajos recursos y del sur tenían menos probabilidad de haber escuchado de I=I. El haber tenido una discusión clínica reciente sobre PrEP o el ser un ex usuario de PrEP se asociaron con la confianza en I=I. La disposición a participar de CAS se asoció positivamente con la confianza en I=I, y varió en función del estado serológico de las parejas, el uso de PrEP y la carga viral. Aunque encontramos altas tasas de conciencia y bajos niveles de desconfianza, nuestro estudio indicó que comunidades clave siguen sin conocer y/o escépticas de I=I.

Introduction

The use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs to achieve viral suppression in people living with HIV is key to combination prevention strategies (1). Treatment as Prevention (TasP), the term coined to describe using viral load suppression as a prevention strategy, originated from the idea that individuals with undetectable viral concentration would be less infectious, and thus unable to transmit HIV to sexual partners (2). Early empirical data supported this hypothesis (3), and observational studies affirmed the association between viral suppression and unstramittability of infection (2, 4). Two recent randomized control trials among serodiscordant couples, PARTNER and Opposites Attract, proved the underlying hypothesis of TasP empirically (5, 6). In PARTNER, there were no documented cases of within-couple HIV transmission; Opposites Attract confirmed the findings in nearly 35,000 condomless anal intercourse acts among men who have sex with men (MSM) where the HIV-negative partner was not taking pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Based on this evidence, in 2016, the Prevention Access Campaign (PAC) created and disseminated a new public health campaign branded “Undetectable equals Untrasmittable” (U=U) to spread the information and help decrease HIV stigma (7). In 2017, the CDC and the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) endorsed TasP (8), and in 2019, the two institutions explicitly backed the U=U campaign by stating its name and scientific rigor (9). By 2019, over 960 organizations from 99 countries had signed up to share the U=U message with PAC (10); a substantial majority being from the U.S. Despite endorsements from U.S. federal authorities and the wide-spread public health community acceptance of the U=U campaign, very few studies have since investigated the reach of U=U messaging to key populations and their attitudes towards it. In the U.S., support for implementation and dissemination research has traditionally been much lesser that of primary and clinical research, which often can impact the reach and positive effects of newer developments to the larger population (11). In 2018, for example, researchers found that only 55% of MSM of diverse serostatus in the U.S. thought the U=U message was completely or somewhat accurate; acceptance of U=U (i.e. the belief that the message is accurate) was only 54% among HIV-negative MSM (12). Recently, it has been suggested that community-driven dissemination interventions may be more effective than national-level ones (13), however the topic remains understudied.

Given the number of resources devoted to this campaign and its potential to impact HIV-related knowledge and reduce stigma (14, 15); monitoring and surveillance of U=U messaging is of major public health importance. This study aimed to understand the level of awareness of U=U in a national sample of HIV-negative cisgender men, trans men and trans women who have sex with men and not taking pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Additionally, we explored characteristics associated with trusting, not trusting and being unsure of U=U messaging, as well willingness to engage in various sexual behaviors based on a partner’s serostatus, PrEP use, and viral load.

Methods

Original study and sample

Data used for this analysis were from the Together 5,000 study, an internet-based, U.S. national cohort of cisgender men, trans men and women who have sex with men. Enrollment procedures for the study are described elsewhere (16, 17). In brief, participants were enrolled via ads on geosocial networking apps between October 2017 and June 2018. Participants clicking on our ads were routed to a secure online survey where eligibility was ascertained, and informed consent was obtained - free of compensation.

To be eligible for enrollment, participants had to self-identify as male, trans male or trans female; be aged 16 to 49; report at least 2 male sex partners in past 90 days; not currently be enrolled in a PrEP clinical study or an HIV-vaccine trial; be living within the U.S. or its territories; not be taking PrEP at the time of enrollment; self-report an HIV status of negative or unknown; and meet at least one additional criteria including several clinically objective as well as self-reported HIV risk, such as recent (i.e., past 12-months) diagnosis of a sexually transmitted infection (STI), self-reported recent CAS with a man (i.e., past 3-months), use of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) (i.e., past 12-months), sharing of needles and/or use of methamphetamine (i.e., past 3-months).

In total, 8755 individuals met out eligibility criteria. These participants were emailed and texted a link to an additional survey which included measures of interest in the present study. Overall, 6267 participants completed this second survey and received a $15 amazon.com gift card. Six months following enrollment, participants were sent a link to an optional follow-up survey that included the remaining measures used in this analysis. For completing the 6-month follow-up survey, participants were entered in a drawing for one of five $200 Amazon gift-cards. In total, 3848 participants—61.4% of those who completed secondary surveys—completed the optional 6-month survey. We excluded participants who self-reported an incident HIV infection or who reported starting PrEP between enrollment and the 6-month follow-up to avoid biased interpretations of risk perceptions measured in the survey items related to U=U. Our final sample consisted of 3286 participants who completed the 6-month optional survey, were not HIV-positive, and were not on PrEP at the time of assessment.

Variables

Demographic characteristics.

Measures of interest for the present study included demographic characteristics that describe the social determinants of health of each participant such as their physical characteristics, wealth and regional area. Age was categorized into four groups (< 25, 25–29, 30–39, and 40+). Race or ethnicity was coded into 5 distinct groups (White, Black/African American, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, multiracial), while sexual identity was coded into three groups (gay/queer, bisexual, straight/other) and gender identity was coded dichotomously (cisgender, transgender/non-binary). Annual income was categorized and recoded into 4 groups based on self-reported income (< $20,000, $20,000 - $50,000, $50,000 - $100,000, $100,000+). Participants provided contact information including ZIP code which was then used to determine their state and U.S. region of residence (Northeast, South, Midwest, and West). Puerto Rico was included in the South, and all other U.S. Territories in the West.

Healthcare Access.

At enrollment, participants were asked whether they had health insurance; a primary care provider (PCP); and whether their PCP were aware of their sexual behavior. Each of these items were coded dichotomously (yes/no). This information was not reassessed on the brief optional 6-month survey, therefore the current analysis uses participant responses recorded at enrollment.

Previous experience with PrEP.

Participants were asked whether they had ever taken PrEP, prior to enrollment or in the six months between enrollment and the follow up survey. We created a dichotomous variable (yes/no) distinguishing those with prior experience to those without. As previously stated, no participants currently taking PrEP were included in the analyses.

Recent discussion of PrEP with a provider.

The 6-month survey asked participants whether they had discussed PrEP with a provider since enrolling in the study, “Since joining this study (in the last 6 months) have you spoken to a medical provider about starting Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)”. Their answers were coded into a dichotomous variable (yes/no).

Undetectable equals Untransmittable (U=U) variables.

The 6-month survey assessed awareness and attitudes towards U=U. First, participants were asked, “Have you heard of the statement HIV Undetectable = Untransmittable or U=U?” (yes/no). Next, participants were presented the following statement:

Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U) is a new HIV prevention initiative. It says that a person living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy (ART) with an undetectable HIV viral load in their blood for at least six months cannot transmit HIV through sex. It has been endorsed by leading HIV researchers as well as the US Centers for Disease Control.

Following this description, participants were asked: “How much do you trust that someone who is HIV undetectable cannot transmit HIV during sex (Undetectable = Untransmittable)” – a 5-item variable ranking from 1- Very Trustworthy to 5 – Very Untrustworthy which was trichotomized into those that “trust U=U” (the first two items), those who “do not trust U=U” (the last two items), and those who were “unsure of U=U” by having answered “3- I am not sure”.

Likelihood of engaging in condomless sex under various scenarios.

Participants were presented a scenario in which each follow up question contained additional information about a potential sexual partner. They were asked about the likelihood they would have CAS with a potential partner either as the insertive partner (top) or the receptive partner (bottom). They were then presented additional information about that partner. For example, participants were presented with the core prompt of “how likely would you be to have condomless anal sex as a top…” followed by,

with a partner who is HIV-negative.

with a partner who is HIV-negative and on PrEP.

with a partner who is HIV-positive.

with a partner who is HIV-positive and undetectable.

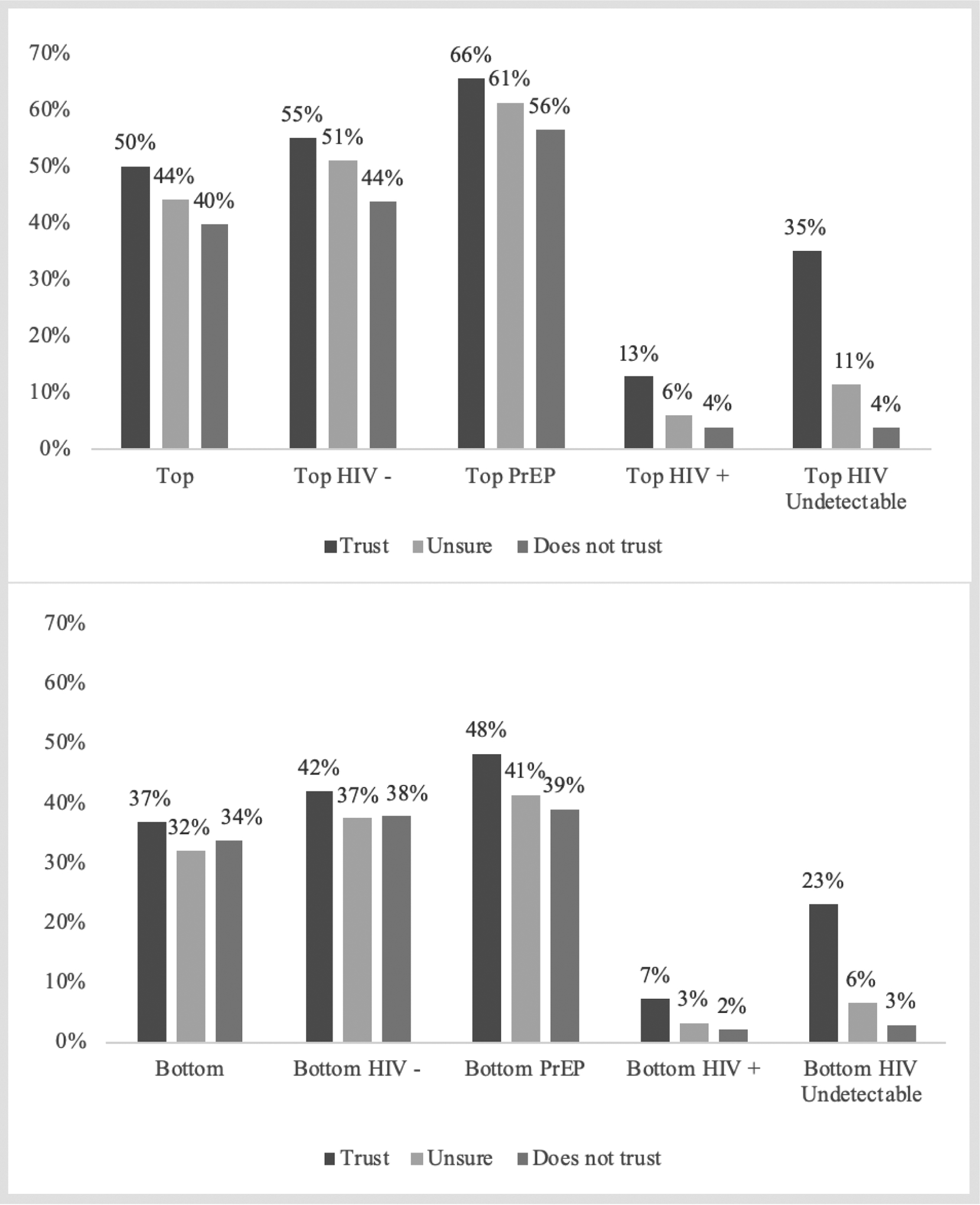

Based on participants answers, ten items were developed, each ranked from 1 Very unlikely to 9 Very likely, with the middle option 5 unsure. Each item contained the participants’ answer for the behavior as top and as bottom for the core prompt, as well as for each of the 4 scenarios listed above. Ten distinct dichotomous variables were developed by grouping participants who ranked five or less under “not likely/unsure” and those who ranked a value greater than five under category “likely”. Figure 1 provides a visual description of the variable construction.

Figure 1.

Distribution of participants attitudes towards engaging in hypothetical CAS with partners of various serostatus, PrEP use and/or viral load - both as top (above) and bottom (below)

Analysis plan

We compared demographic, healthcare- and biomedical prevention-related questions for participants who had heard of U=U and those who had not. We made these same comparisons for the three groups of participants who reported trusting, distrusting or being unsure of U=U. Next, we built two graphs for the distribution of their answers about engaging in CAS with male partners in different scenarios for the three groups- one for top and one for bottom behavior. We then conducted bivariate analyses to assess differences in the distributions of all variables between the two awareness-related groups, as well as among the three trust-related groups using chi-square tests. Additionally, we developed a multivariable logistic model, which included all independent variables, to explore factors associated with having heard of U=U versus not. Finally, we conducted a multivariable, multilevel logistic regression to explore factors associated with trusting, not trusting or being unsure of U=U. We set p < 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance. All analysis were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (18).

Results

Sample Demographics.

Table 1 reports the demographics and biomedical-related characteristics of our participants, as well as baseline healthcare-related variables. Our sample was ethnically and racially diverse with 44% reporting a race other than white; half (50%) were under 30 years old, and overwhelmingly identified as gay/queer (85%), and cisgender male (98%). About three-quarters of our sample reported an income of $50,000 or less. The U.S. South was the region most represented (46%), followed by the West (23%). Eighty-six percent of our participants reported no prior experience with PrEP, however about 30% had conversation about PrEP with a provider in the past six months. At enrollment, about three-quarters (75%) of participants reported having health insurance, about half (53%) reported having a PCP, and among those, 70% said their PCP knew they had sex with men. In total, 85% of participants reported having heard of U=U and, out of those, only 42% indicated they trusted it, the remainder said they did not trust it (20%) or were unsure about it (38%).

Table 1.

Demographics and Healthcare variables

| Among those who have heard about U=U (n = 2809) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Heard about U=U | Has not heard about U=U | Trusts U=U | Unsure about U=U | Distrusts U=U | |||||||||||

| 3286 | 2809 | 477 | 1187 | 42.3% | 1067 | 38.0% | 555 | 19.8% | ||||||||

| Demographics | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p-value | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p-value |

| Age | 7.22 | 0.065 | 9.39 | 0.153 | ||||||||||||

| <25 | 750 | 22.8% | 619 | 22.0% | 131 | 27.5% | 271 | 22.8% | 240 | 22.5% | 108 | 19.5% | ||||

| 25–29 | 884 | 26.9% | 768 | 27.3% | 116 | 24.3% | 347 | 29.2% | 274 | 25.7% | 147 | 26.5% | ||||

| 30–39 | 1072 | 32.6% | 925 | 32.9% | 147 | 30.8% | 366 | 30.8% | 356 | 33.4% | 203 | 36.6% | ||||

| 40+ | 580 | 17.7% | 497 | 17.7% | 83 | 17.4% | 203 | 17.1% | 197 | 18.5% | 97 | 17.5% | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 14.86 | 0.005* | 35.75 | <0.001** | ||||||||||||

| White | 1826 | 55.6% | 1589 | 56.6% | 237 | 49.7% | 729 | 61.4% | 587 | 55.0% | 273 | 49.2% | ||||

| Black | 296 | 9.0% | 256 | 9.1% | 40 | 8.4% | 99 | 8.3% | 99 | 9.3% | 58 | 10.5% | ||||

| Latinx | 752 | 22.9% | 621 | 22.1% | 131 | 27.5% | 212 | 17.9% | 251 | 23.5% | 158 | 28.5% | ||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 126 | 3.8% | 98 | 3.5% | 28 | 5.9% | 36 | 3.0% | 40 | 3.7% | 22 | 4.0% | ||||

| Multiracial | 286 | 8.7% | 245 | 8.7% | 41 | 8.6% | 111 | 9.4% | 90 | 8.4% | 44 | 7.9% | ||||

| Income | 23.68 | <0.0001** | 14.85 | 0.02* | ||||||||||||

| < $20,000 | 1019 | 31.0% | 830 | 29.5% | 189 | 39.6% | 361 | 30.4% | 335 | 31.4% | 134 | 24.1% | ||||

| $20,000 – $50,000 | 1386 | 42.2% | 1197 | 42.6% | 189 | 39.6% | 507 | 42.7% | 442 | 41.4% | 248 | 44.7% | ||||

| $50,000 – $100,000 | 668 | 20.3% | 599 | 21.3% | 69 | 14.5% | 248 | 20.9% | 228 | 21.4% | 123 | 22.2% | ||||

| $100,000+ | 213 | 6.5% | 183 | 6.5% | 30 | 6.3% | 71 | 6.0% | 62 | 5.8% | 50 | 9.0% | ||||

| Sexual orientation | 6.83 | 0.03* | 55.05 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Gay | 2801 | 85.2% | 2411 | 85.8% | 390 | 81.8% | 1075 | 90.6% | 906 | 84.9% | 430 | 77.5% | ||||

| Bisexual | 449 | 13.7% | 366 | 13.0% | 83 | 17.4% | 101 | 8.5% | 149 | 14.0% | 116 | 20.9% | ||||

| Straight/Other | 36 | 1.1% | 32 | 1.1% | 4 | 0.8% | 11 | 0.9% | 12 | 1.1% | 9 | 1.6% | ||||

| Gender identity | 0.65 | 0.42 | 4.28 | 0.12 | ||||||||||||

| Cisgender | 3213 | 97.8% | 2749 | 97.9% | 464 | 97.3% | 1154 | 97.2% | 1048 | 98.2% | 547 | 98.6% | ||||

| Transgender/Non-Binary | 73 | 2.2% | 60 | 2.1% | 13 | 2.7% | 33 | 2.8% | 19 | 1.8% | 8 | 1.4% | ||||

| Region | 1.00 | 0.8 | 39.79 | <0.001** | ||||||||||||

| Northeast | 509 | 15.5% | 429 | 15.3% | 80 | 16.8% | 194 | 16.5% | 164 | 15.7% | 71 | 13.1% | ||||

| South (includes PR) | 1513 | 46.0% | 1301 | 46.3% | 212 | 44.4% | 478 | 40.6% | 517 | 49.6% | 306 | 56.5% | ||||

| Midwest | 518 | 15.8% | 444 | 15.8% | 74 | 15.5% | 203 | 17.3% | 170 | 16.3% | 71 | 13.1% | ||||

| West (includes HI,AK, Military Overseas) | 746 | 22.7% | 635 | 22.6% | 111 | 23.3% | 312 | 26.5% | 216 | 20.7% | 107 | 19.7% | ||||

| Prior experience with PrEP | 8.08 | 0.0045* | 38.59 | <0.001** | ||||||||||||

| No | 2817 | 85.7% | 2388 | 85.0% | 429 | 89.9% | 952 | 80.2% | 937 | 87.8% | 499 | 89.9% | ||||

| Yes | 469 | 14.3% | 421 | 15.0% | 48 | 10.1% | 235 | 19.8% | 130 | 12.2% | 56 | 10.1% | ||||

| Has spoken to a provider about PrEP in the last 6 months | 17.33 | <0.001** | 67.94 | <0.001** | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 944 | 28.7% | 845 | 30.1% | 99 | 20.8% | 456 | 38.4% | 254 | 23.8% | 135 | 24.3% | ||||

| No | 2342 | 71.3% | 1964 | 69.9% | 378 | 79.2% | 731 | 61.6% | 813 | 76.2% | 420 | 75.7% | ||||

| Health insurance at baseline | 2.83 | 0.09 | 1.26 | 0.53 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2451 | 74.6% | 2110 | 75.1% | 341 | 71.5% | 900 | 75.8% | 789 | 73.9% | 421 | 75.9% | ||||

| No | 835 | 25.4% | 699 | 24.9% | 136 | 28.5% | 287 | 24.2% | 278 | 26.1% | 134 | 24.1% | ||||

| Has primary care provider at baseline | 1.59 | 0.21 | 5.34 | 0.07 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1741 | 53.0% | 1501 | 53.4% | 240 | 50.3% | 633 | 53.3% | 549 | 51.5% | 319 | 57.5% | ||||

| No | 1545 | 47.0% | 1308 | 46.6% | 237 | 49.7% | 554 | 46.7% | 518 | 48.5% | 236 | 42.5% | ||||

| Primary care provider knows their sexual orientation at baseline (n =1741) | 13.08 | 0.003** | 23.92 | <0.001** | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1211 | 69.6% | 1068 | 71.2% | 143 | 59.6% | 491 | 77.6% | 374 | 68.1% | 203 | 63.6% | ||||

| No | 530 | 30.4% | 433 | 28.8% | 97 | 40.4% | 142 | 22.4% | 175 | 31.9% | 116 | 36.4% | ||||

p -value < 0.05;

p < 0.001

Sexual Behavior.

Figure 1 illustrates differences in the likelihood of CAS with a male partner under various scenarios among our three trust-related groups: those that trust, do not trust, or were unsure about U=U. Overall, participants were more likely to say they would engage in CAS with HIV-negative partners than with HIV-positive partners; however, notably, a clear gradient can be observed across almost all situations based on their level of trust of U=U. Furthermore, across all scenarios, participants were more willing to engage in insertive CAS than receptive. Participants who reported trusting U=U were more likely to report willingness to engage in CAS regardless of the HIV status of the partner. Nevertheless, more participants who reported trusting U=U were willing to engage in CAS with a partner of unknown status than with a partner who is HIV-positive and undetectable, both for when they were told they would be the insertive (top) partner (50% vs 35%), as well as for when they would be the receptive (bottom) partner (37% vs 23%).

Awareness of U=U.

Regression models are shown in Table 2. Our first model, which explored factors associated with not having heard of U=U (vs. had), showed that both Asian/Pacific islander and Latinx participants were at significantly increased odds of not having heard about U=U compared to whites. Additionally, having an income higher than $20,000 a year or having had a recent conversation with a medical provider about PrEP was significantly associated with having heard of U=U.

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression predicting differences between those who have not heard of U=U and those who do not trust or are unsure about U=U

| Model 1 | Model 2a | Model 2b | Model 2c | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds of not having heard of U=U | Odds of not trusting U=U | Odds of being unsure about U=U | Odds of not trusting U=U | ||||||||||||||

| Reference: Having Heard of U=U | Reference: Trusting U=U | Reference: Trusting U=U | Reference: Unsure about U=U | ||||||||||||||

| Characteristics | aOR | 95% Confidence | aOR | 95% Confidence | aOR | 95% Confidence | aOR | 95% Confidence | |||||||||

| Age (Ref: 18–24) | |||||||||||||||||

| 25 – 29 | 0.88 | 0.66 | -- | 1.17 | 1.18 | 0.86 | -- | 1.63 | 1.04 | 0.81 | -- | 1.34 | 1.14 | 0.82 | -- | 1.57 | |

| 30 – 39 | 0.97 | 0.74 | -- | 1.29 | 1.54 | 1.12 | -- | 2.12 | 1.31 | 1.02 | -- | 1.68 | 1.18 | 0.86 | -- | 1.62 | |

| 40+ | 1.12 | 0.80 | -- | 1.57 | 1.25 | 0.86 | -- | 1.83 | 1.34 | 0.99 | -- | 1.81 | 0.94 | 0.64 | -- | 1.37 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (Ref: White) | |||||||||||||||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.86 | 1.19 | -- | 2.93 | 1.85 | 1.04 | -- | 3.28 | 1.53 | 0.95 | 2.46 | 1.21 | 0.70 | -- | 2.10 | ||

| Multiracial | 1.03 | 0.72 | -- | 1.49 | 1.18 | 0.80 | -- | 1.75 | 1.06 | 0.78 | -- | 1.44 | 1.12 | 0.75 | -- | 1.66 | |

| Black/African American | 0.96 | 0.66 | -- | 1.39 | 1.40 | 0.97 | -- | 2.04 | 1.13 | 0.83 | -- | 1.55 | 1.24 | 0.86 | -- | 1.80 | |

| Latinx | 1.33 | 1.05 | -- | 1.70 | 2.22 | 1.70 | -- | 2.89 | 1.56 | 1.24 | -- | 1.95 | 1.42 | 1.10 | -- | 1.84 | |

| Income (Ref: < $20,000) | |||||||||||||||||

| $20,000 - $50,000 | 0.75 | 0.59 | -- | 0.96 | 1.47 | 1.11 | -- | 1.94 | 1.00 | 0.80 | -- | 1.24 | 1.47 | 1.12 | -- | 1.94 | |

| $50,000 – $100,000 | 0.54 | 0.39 | -- | 0.76 | 1.47 | 1.04 | -- | 2.08 | 1.04 | 0.79 | 1.36 | 1.42 | 1.01 | -- | 2.00 | ||

| $100,000+ | 0.73 | 0.46 | -- | 1.17 | 2.30 | 1.44 | -- | 3.69 | 0.99 | 0.65 | -- | 1.49 | 2.34 | 1.46 | -- | 3.76 | |

| Sexual Orientation (Ref: Gay/Queer) | |||||||||||||||||

| Bisexual | 1.31 | 1.00 | -- | 1.71 | 2.81 | 2.08 | -- | 3.80 | 1.68 | 1.27 | -- | 2.21 | 1.68 | 1.27 | -- | 2.21 | |

| Straight/Other | 0.64 | 0.22 | -- | 1.86 | 3.04 | 1.20 | -- | 7.73 | 1.55 | 0.66 | -- | 3.63 | 1.96 | 0.80 | -- | 4.83 | |

| Gender Identity (Ref: Cisgender) | |||||||||||||||||

| Transgender | 1.30 | 0.69 | -- | 2.43 | 0.54 | 0.23 | -- | 1.24 | 0.71 | 0.39 | 1.30 | 0.76 | 0.32 | -- | 1.80 | ||

| Region (Ref: Northeast) | |||||||||||||||||

| South | 0.80 | 0.60 | -- | 1.07 | 1.61 | 1.17 | -- | 2.22 | 1.18 | 0.92 | -- | 1.51 | 1.37 | 1.00 | -- | 1.89 | |

| Midwest | 0.91 | 0.64 | -- | 1.29 | 0.96 | 0.65 | -- | 1.43 | 1.00 | 0.74 | -- | 1.34 | 0.97 | 0.65 | -- | 1.44 | |

| West | 0.88 | 0.64 | -- | 1.21 | 0.85 | 0.59 | -- | 1.23 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 0.77 | -- | 1.61 | ||

| Prior experience with biomedical interventions (Ref: Yes) | |||||||||||||||||

| None | 1.20 | 0.84 | -- | 1.72 | 1.60 | 1.12 | -- | 2.29 | 1.21 | 0.92 | -- | 1.58 | 1.33 | 0.92 | -- | 1.93 | |

| Spoke about PrEP to a provider in the past 6 months (Ref: No) | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.67 | 0.51 | -- | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.48 | -- | 0.81 | 0.56 | 0.45 | -- | 0.69 | 1.11 | 0.85 | -- | 1.46 | |

| Had health Insurance at baseline (Ref: No) | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.05 | 0.82 | -- | 1.34 | 1.06 | 0.81 | -- | 1.38 | 1.02 | 0.83 | -- | 1.27 | 1.03 | 0.79 | -- | 1.35 | |

| Had a Primary Care Provider at baseline (Ref: No) | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.81 | -- | 1.24 | 0.78 | 0.62 | -- | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.83 | -- | 1.20 | 0.78 | 0.62 | -- | 0.98 | |

Trust in U=U.

The next models explored factors associated with trusting, not trusting or being unsure of U=U among those who reported having heard of it. Model 2a explored factors associated with not trusting U=U, using trust as reference. People 30–39 years old had higher odds of reporting not trusting compared to participants under 24. Similarly, being Asian/Pacific Islander or Latinx, bisexual, and reporting an annual income greater than $20,000 was associated with greater odds of not trusting U=U. Those who reported prior experience with PrEP were significantly more likely to report trusting U=U. Participants who reported having had a conversation with a medical provider about PrEP in the last six-months, and those who reported having a PCP during baseline were significantly more likely to trust U=U. The next model (2b) reports factors associated with being unsure about U=U, using trust as reference. Participants who were 30–39 year old had significantly higher odds of being unsure about U=U. Latinx had 1.5-fold increased odds of being unsure about U=U; bisexual participants, similarly, had significantly higher odds of being unsure of U=U. Lastly, participants who discussed PrEP with a provider in past six-months had two-fold odds of trusting U=U. The last model used not trusting U=U as the outcome variable and being unsure as reference. Compared to white participants, Latinx had significantly higher odds of not trusting U=U; as did participants who were bisexual and those reporting an annual income greater than $20,000. Reporting a PCP at enrollment was associated with lower odds of not trusting U=U.

Discussion

While the U=U message has gained strong political and community support in the U.S and worldwide, very little has been done to monitor its breadth and reach to key communities. In a large national sample of individuals without HIV, we found that Latinx and Southerners are more likely to be unaware and to distrust or be unsure of U=U. However, having prior PrEP use or a recent discussion about PrEP with a medical provider was associated with increased awareness and trust in U=U. Lastly, we found that trust in U=U was associated with different sexual behaviors depending on the partner’s serostatus, PrEP use and/or viral load. To date, this is one of a few studies exploring factors associated with awareness and knowledge of U=U messaging.

Most participants (85%) indicated being aware of U=U, however less than half of these participants (42.5%) indicated they trusted it. Previous research has showed a similar pattern, with over half of HIV-negative participants indicating they believed the message of U=U to be inaccurate; odds were higher for Latinx and participants not on PrEP (12). While our study found somewhat lower trust in U=U compared to that found by Rendina, et. al. (42.5% vs 55% of participants), both studies highlight the need to better understand gaps in U=U messaging. Neither study collected follow up answers to participants reasonings around trust in U=U, therefore we were unable to tease apart reasons why, despite being aware, individuals would distrust or rate the message inaccurate; however, our findings suggest that there is opportunity to address this gap as 38% of our participants were unsure about their trust in U=U. Future research should seek to understand individuals’ specific concerns about distrusting U=U. For example, it could be that individuals trust the science behind U=U but are less trusting of their partners’ self-reported serostatus and may have answered the questions with that in mind. HIV stigma may also be influencing individual perspectives by continuing to classify people living with HIV as undesirable or infectious sex partners. A better understanding of the precise reasons why someone would distrust a scientific sounding fact is needed to allocate and develop resources in communities impacted by HIV.

We found noteworthy discrepancies among those who have heard of U=U and either trusted, distrusted or were unsure of it. Latinx were more likely to have not heard of U=U, and across all our regression models there was a positive association between being Latinx and not trusting or being unsure of U=U. Previous research has indicated that HIV-negative or unknown serostatus Latinx across the United States are more likely to be unsure what “undetectable” means (12), further affirming the relevance of this finding. A similar pattern was observed in participants residing in the southern United States, whereby those who reported living in this region were more likely to report not trusting U=U. Both findings present specific areas where efforts and resources can be allocated to increase knowledge and awareness of U=U. This is especially important to communities that are disproportionally impacted by HIV. According to 2016 estimates from the CDC, Latinx MSM have a one-in-four chance of contracting HIV in their lifetime (19), while the U.S. South represents the region with highest incidence of HIV and lowest sero awareness in the country (19). In here we have the opportunity to increase efforts to expand U=U messaging to communities that can directly benefit from decreased stigma and a shift in messaging around an HIV diagnosis. It is important to note that our analysis did not find statistical significance with regards to being Black or African American, despite our measurement of association trending towards the same direction that of Latinx, although smaller in magnitude. It may be that our study had a smaller percentage of Blacks compared to Latinx (9% vs. 23%), and perhaps with a larger sample of Black participants that association would achieve statistical significant.

In our study, a prior use or even a clinical consultation about PrEP was shown to be positively associated with both awareness of and trust in U=U. These findings suggest that learning about biomedical interventions for staying HIV-negative may be associated with also learning about HIV-positive biomedical interventions, such as TasP. It has been reported that HIV-negative cisgender and transgender men on PrEP are more likely to accurately recognize the meaning of “undetectable” (12), which further supports our hypothesis. Although it is often difficult to measure the direct impact of public health messaging, our findings suggest that when individuals consider initiating PrEP (i.e. by talking to their provider about it) they may be exposed to information about other types of biomedical interventions or become primed to notice such information, which may include those targeting HIV-positive people. This finding further supports the case for continued integration of PrEP assessment and care into routine primary care practice.

Lastly, our study showed some dissonance between participants’ trust in U=U relative to the behaviors they would engage in with potential sex partners (Figure 1). Overall, people who trusted U=U would be more likely to have CAS with a partner who was HIV-positive than people who did not trust U=U; these patterns suggest that participants would be more likely to top than to bottom, highlighting some skepticism with regards to trust in U=U and their sexual positioning. Noteworthy, this does recognize that inherent risks to HIV transmission are greater when one bottoms than when one tops, and participants could be referring to the concept known as sero-positioning (i.e. moderating HIV risk by topping instead of bottoming). This pattern was repeated in that participants said they would be more likely to top a partner on PrEP than to bottom for him. Finally, we note that participants were overall more likely to indicate they would have sex with a partner without a condom when they were not given any information about that partner’s HIV status (i.e how likely are you to do the following with a casual male partner? Top/Bottom without a condom?) than when they were told this partner was HIV-positive and virally suppressed (i.e. how likely are you to do the following with a casual male partner? Top/Bottom without a condom with a partner who is HIV-positive and undetectable?). Here too we see the recapitulation of the inherent fear of having sex with someone who is known to be living with HIV, essentially, even when trusting U=U, people may still make a cognitive error in assessing relative risk, assuming that someone living with HIV is somehow a greater threat than someone with an unknown status—who inarguably poses a greater threat with regard to transmission. Thus, these data clearly indicate that the work to reduce HIV stigma is not done.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. Data were self-reported, which can raise concerns related to social desirability—whereas self-administration of surveys (as opposed to face-to-face) can help reduce such biases (20). Next, the timing the survey answers were collected is important since U=U messaging is active and ongoing; our survey answers were collected in 2018, and perhaps we would find different results should the data collection occurred more recently. We also did not confirm the extent to which someone understands the meaning of U=U; simply asking individuals whether they were aware of the concept and then presenting them with a definition. We did not ask individuals who taught them about U=U or when did they learn about it, which did not allow us to verify sources or how long individuals have had access to this information, this information can be a source of confounding which we could not control for during our analysis.

To measure attitudes and sexual preferences towards partners of various status, our study focused on likelihood of engaging in condomless anal sex, and some participants may not engage in such type of sex, although all participants reported sex with men to be eligible for enrollment. While the majority of our sample was composed of cisgender men, there were transgender individuals who may or may not have other receptive body parts (i.e., vagina, neo-vagina) which may carry similar or higher risk for HIV acquisition. Our study did not explore any risk related to vaginal sex. A sensitivity analysis (data not shown), however, indicated that over 96% of the sample (97% of transgender and non-binary participants) said they had anal sex with a male partner in the three-month period prior to enrollment into the study. Similarly, we did not ask participants about potential sexual agreements they may have with regular or primary partners, and therefore could not explore the role of these in our samples risk assessment. Participants may have drawn their answers from their current sexual agreements.

Lastly, we also note that not all participants who were eligible for the study ultimately participated in all study procedures. In a separate publication, we reported that those retained in study procedures were more likely to be white; however, the attrition of people of color, while statistically significant in part because of our large sample size, was not large in magnitude (16). Observed higher attrition among participants of color has been noted in other research studies (21, 22).

Conclusion

U=U messaging can boost HIV prevention efforts by neutralizing the stigma associated with being HIV-positive which, in turn, may increase uptake in HIV testing and treatment (i.e. viral load and thus infectiousness toward partners). By knowing of and understanding U=U, LGBTQ and minority communities can shift the messaging around HIV statuses by encouraging testing and seroawareness. To be successful as an initiative, however, those affected or impacted by HIV need to be familiar with U=U messaging and trust it. Our findings underscore the need to continue developing strategies to spread community awareness and build trust around the message of U=U.

We found important demographic differences in populations who have heard and haven’t heard of U=U, as well as differences in those who trust, distrust or are unsure about U=U. Our findings showed that despite important strides being done to launch the U=U campaign across the country, there are still significant gaps in knowledge and trust across key populations. Future research should focus on the specific reasons why someone would distrust U=U and how to foster more trust in U=U.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to additional members of the T5K study team: Denis Nash, David Pantalone, Sarit A. Golub, Gregorio Millett, Don Hoover, Sarah Kulkarni, Matthew Stief, Alexa D’Angelo, Chloe Mirzayi, Corey Morrison, Fatima Zohra, & Javier Lopez-Rios. Thank you to the members of our Scientific Advisory Board: Adam Carrico, Michael Camacho, Demetre Daskalakis, Sabina Hirshfield, Jeremiah Johnson, Claude Mellins, and Milo Santos. And thank you to the program staff at NIH: Gerald Sharp, Sonia Lee, and Michael Stirratt. While the NIH financially supported this research, the content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect official views of the NIH.

We also like to thank the anonymous reviewer who provided indispensable commentary that helped shape the interpretation of our results

Funding: Together 5,000 was funded by the National Institutes for Health (UG3 AI 133675 - PI Grov). Viraj Patel was supported by a career development award (K23MH102118). Other forms of support include the CUNY Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health, the Einstein-Rockefeller-CUNY Center for AIDS Research (ERC CFAR, P30 AI124414).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Collaboration H-C. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS (London, England). 2010;24(1):123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernazza P, Hirschel B, Bernasconi E, Flepp M. Les personnes séropositives ne souffrant d’aucune autre MST et suivant un traitement antirétroviral efficace ne transmettent pas le VIH par voie sexuelle. Bulletin des médecins suisses| Schweizerische Ärztezeitung| Bollettino dei medici svizzeri. 2008;89(5):165–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(9):830–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, Van Lunzen J, et al. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Jama. 2016;316(2):171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bavinton BR, Pinto AN, Phanuphak N, Grinsztejn B, Prestage GP, Zablotska-Manos IB, et al. Viral suppression and HIV transmission in serodiscordant male couples: an international, prospective, observational, cohort study. The lancet HIV. 2018;5(8):e438–e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prevention Access Campaign. Risk of Sexual Transmission of HIV from a Person Living with HIV Who Has an Undetectable Viral Load: Messaging Primer & Consensus Statement 2016. [Available from: https://www.preventionaccess.org/consensus.

- 8.McCray E, Mermin JH. Dear Colleague: September 27, 2017. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisinger RW, Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. HIV viral load and transmissibility of HIV infection: undetectable equals untransmittable. Jama. 2019;321(5):451–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prevention Access Campaign. Community Partners 2020. [Available from: https://www.preventionaccess.org/community.

- 11.Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National Institutes of Health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. American journal of public health. 2012;102(7):1274–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rendina HJ, Parsons JT. Factors associated with perceived accuracy of the Undetectable=Untransmittable slogan among men who have sex with men: Implications for messaging scale-up and implementation. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2018;21(1):e25055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrato EH, Rabin B, Proctor J, Cicutto LC, Battaglia CT, Lambert-Kerzner A, et al. Bringing it home: expanding the local reach of dissemination and implementation training via a university-based workshop. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baltimore City Health Deparment. Our Stories - UU 2020 [Available from: https://www.uequalsumaryland.org/our-stories/.

- 15.The Well project. Undetectable Equal Unstrasmittable: Building Hope and Ending HIV Stigma 2020. [Available from: https://www.thewellproject.org/hiv-information/undetectable-equals-untransmittable-building-hope-and-ending-hiv-stigma.

- 16.Grov C, Westmoreland DA, Carneiro PB, Stief M, MacCrate C, Mirzayi C, et al. Recruiting vulnerable populations to participate in HIV prevention research: findings from the Together 5000 cohort study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nash D, Stief M, MacCrate C, Mirzayi C, Patel VV, Hoover D, Pantalone DW, Golub S, Millett G, D’Angelo AB, Westmoreland DA. A web-based study of HIV prevention in the era of pre-exposure prophylaxis among vulnerable HIV-negative gay and bisexual men, transmen, and transwomen who have sex with men: Protocol for an observational cohort study. JMIR research protocols. 2019;8(9):e13715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAS Institute Incorporated. SAS 9.4 ed. Cary, NC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC. Trends in US HIV diagnoses, 2005–2014. Fact Sheet. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.King MF, Bruner GC. Social desirability bias: A neglected aspect of validity testing. Psychology & Marketing. 2000;17(2):79–103. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khosropour CM, Sullivan PS. Predictors of retention in an online follow-up study of men who have sex with men. Journal of medical Internet research. 2011;13(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma A, Sullivan PS, Khosropour CM. Willingness to take a free home HIV test and associated factors among internet-using men who have sex with men. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2011;10(6):357–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]