Abstract

Objectives

Determine the validity and reliability of a remote, technician-guided cognitive assessment for MS, incorporating the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) and the California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition (CVLT-II).

Methods

In 100 patients, we compared conventional in-person testing to remote, webassisted assessments, and in 36 patients, we assessed test-retest reliability using two equivalent, alternative forms.

Results

In-person and remote administered SDMT (r=0.85) and CVLT-II (r=0.71) results were very similar. Reliability was adequate and alternative forms of SDMT (r=0.92) and CVLT-II (r=0.81) produced similar results.

Conclusions

Findings indicate remote assessment can provide valid, reliable measures of cognitive function in MS.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, cognitive impairment, CVLT-II, SDMT

INTRODUCTION

Full characterization of cognitive ability in MS requires psychometric assessment using tests that require a human interface that is a neuropsychologist or similarly trained professional. This is not practical for large clinical or epidemiologic studies, which need data collected on several hundreds or thousands of participants. Thus, an easily administered, inexpensive and sensitive assessment tool that could be utilized remotely would facilitate large studies of risk factors for cognitive health in MS. Such a tool could also facilitate clinical management by early identification of cognitive deficits.

Several computerized assessments for cognitive function were validated in MS samples although extent of examiner oversight is debated.1 Further,computer-assistedmethods do not incorporate voice recognition methodology, and as such, memory tests are restricted to recognition, not recall memory. The California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition (CVLT-II)2 and the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)3 are validated performance tests of episodic memory and processing speed that comprise part of the recommended Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS (BICAMS).4 Alternative forms of the SDMT show excellent reliability and equivalence.5

We developed a technician guided, web-based tool to measure cognition using the CVLT-II and the SDMT. Previously, we determined the feasibility of a remote assessment protocol6 by comparing telemedicine CVLT-II data from MS patients to data acquired in person from an independent sample of cases and controls. CVLT-II assessments by conventional in-person and remote assessment yielded indistinguishable results. Herein, we aimed to replicate these results and extend them to the SDMT.

METHODS

MS cases were adult members of the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Plan in Northern California Region (KPNC), an integrated health services delivery system. A total of 100 MS cases were studied for cognitive assessment validation. An independent sample of 36 cases were studied for cognitive assessment reliability. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at UC Berkeley and Kaiser Permanente Division of Research. All study participants provided informed consent. The staff interviewer was formally trained in administering the SDMT, CVLT-II, and multiple equivalent forms of SDMT and CVLT-II, and conducted all remote assessments using the same procedure. For further details, see Supplementary Materials.

To validate remotely administered SDMT and CVLT-II, we assigned 50 participants to receive the in-person assessments followed by remote assessment, and 50 participants to receive the reverse order. Similarly, to test the reliability of two equivalent, alternative forms of remote-administered SDMT and CVLT-II, we assigned 18 participants to receive Version 1 followed by Version 2 (SDMT) and standard followed by alternative forms (CVLT-II), and 18 participants to receive the reverse order, respectively. All in-person and remote assessments were scheduled 1–2 weeks apart.

RESULTS

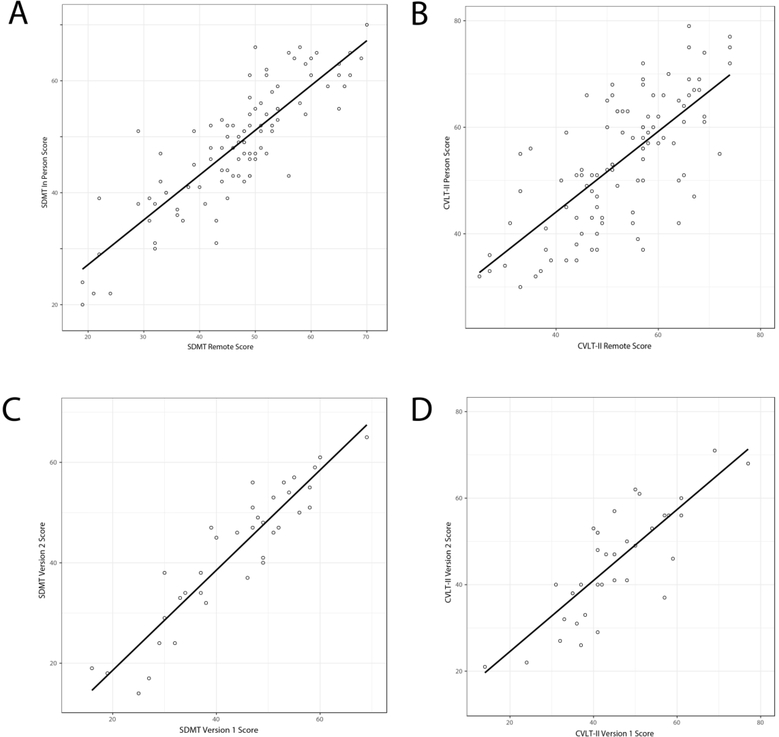

Subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. Remote and in-person assessments of SDMT were strongly and significantly correlated (r=0.85, p<1.0×10−28) (Figure 1A). Similar results were observed for CVLT-II testing (r=0.71, p<1.0×10−15) (Figure 1B). Correlations did not significantly change depending on order of assessment: in-person (SDMT p<1.0×10−13, CVLT-II p<1.0×10−8) or remote (SDMT p<1.0×10−12, CVLT-II p<1.0×10−8) administered first (data not shown). Parallel versions of SDMT (r=0.92, p<1.0×10−14) and CVLT-II (r=0.81, p<1.0×10−10) were highly correlated (Figures 1C and 1D).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Kaiser Permanente Northern California Region (KPNC) MS casesin validation and reliability study samples

| Mean (SD) or Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Validation Sample | Reliability Sample |

| Number of individuals | 100 | 36 |

| Age at assessment (years) | 58.2 (9.4) | 56.8 (9.2) |

| Sex (Female) | 81 (81%) | 25 (69.4) |

| Disease subtype (RRMS and SPMS) | 86 (86%) | 28 (77.8) |

| Education (any college) | 93 (93%) | 31 (86.1) |

| Race and ethnicity (White, non-Hispanic/Black/Other) | 86 (86%)/13 (13%)/1 (1%) | 36 (100%)/0/0/0 |

| Disease duration (years) | 25.5 (10.0) | 22.9 (9.4) |

| PHQ-9 score | 16.8 (5.6) | 16.7 (4.8) |

| MSNQ score | 18.9 (11.7) | 19.0 (12.0) |

Figure 1.

Comparison of remote and in-person A) SDMT assessments and B) CVLT-II assessments, and comparison of remote administered equivalent, alternative forms of C) SDMT and D) CVLT-II. Pearson correlations were used to assess relationships between remote and in-person administrations of the SDMT and CVLT-II (validation study) and alternative forms of the remote-administered SDMT and CVLT-II (reliability study). Statistical analyses were conducted using R.

Linear regression results showed that males and individuals with no college education had worse CVLT-II scores (ß=−7.36, p=0.003; ß=-7.92, p=0.03, respectively) compared to female and college educated individuals (Supplementary Table 1). A self-reported history of recent relapse was associated with worse CVLT-II (ß=−6.32, p=0.02) and SDMT (ß=−5.36, p=0.06) scores. Longer disease duration was associated with worse SDMT scores (ß=−0.29, p=0.02).

DISCUSSION

Results indicate SDMT and CVLT-II data collected through remote, web-based, technician-guided administration yield similar results to standard, validated in-person measures of the same assessments. Further, two alternative, parallel forms of remotely assessed SDMT and CVLT-II show high reliability, indicating either form can be used to obtain equivalent SDMT or CVLT-II results. These web-based assessments show promise for appraisal of cognition when circumstances prevent patient attendance in the neurology clinic.

Our work represents an initial effort to address the challenges of cognitive testing in MS by measuring episodic memory and processing speed remotely. While the MS data indicate the remote and conventional data are roughly equivalent, it remains to be seen whether new normative data are needed for clinical utilization. Notably, the BICAMS recommended visual memory test, the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test Revised, was not included in this study because a manual response (drawing figures from memory) is required. While one can envisage how current videoconference technology might overcome this limitation, we have not pursued such a course, to date. We acknowledge that the BVMTR is recognized as a sensitive test in MS. Furthermore, this research was supported by national funding. It remains to be seen if the work will translate to an insurance-based, routine clinical practice, that can retain adherence to these protocols to maintain reliability.

Experiencing a self-reported recent relapse was associated with worse CVLT-II and SDMT scores. Notably, ~18% of MS cases reported having a relapse within 4 weeks prior to cognitive testing; ~75% of these individuals were relapsing at time of study (overall ~13% of all participants). Cognitive decline occurs in relapses and can be missed by routine neurological care. In a recent study, SDMT scores significantly declined from baseline when MS patients experienced a relapse and recovered to slightly below baseline levels three months later.7 CVLT-II scores had similar but trending results. Our results strongly agree with these findings; however, more work is need. Assessing patients in a guided, remote manner ensures reliable assessment of cognition on an as-needed basis and could detect cognitive relapses.

By assessing memory in patients prior to a clinic visit using a web-based approach, we may be able to meet the goal of routine neurocognitive monitoring of MS patients, as recently suggested.8 A positive test could identify individuals with early cognitive impairment who are at increased risk of job loss, acute disease activity and rapid disease progression. MS clinic staff could be alerted prior to patient visits. Patients who are at greatest risk for cognitive impairment or who present with cognitive impairment could be targeted for intervention strategies to improve cognitive function.

RHBB received honoraria or speaking fees from Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono and Novartis, provided consultancy for Biogen, Celgene, Medday, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, and Verasci, and has received research support from Biogen, Genentech, Genzyme, Mallinckrodt, and Novartis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [R01 ES017080], the National Institute of Nursing Research [R01 NR017431], and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society [RG 1607-25181].

REFERENCES

- 1.Wojcik CM, Beier M, Costello K,et al.Computerized neuropsychological assessment devices in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. Epub ahead of print 2019. 10.1177/1352458519879094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delis DC,Kramer JH, Kaplan E,et al. California Verbal Learning Test - second edition. Adult version. Manual. 2000.

- 3.Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test(SDMT) Manual(revised). Los Angeles: Westerrn Psychological Services, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langdon DW, Amato MP, Boringa J, et al. Recommendations for a brief international cognitive assessment for multiple sclerosis(BICAMS). Multiple Sclerosis Journal. Epub ahead of print 2012. 10.1177/1352458511431076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedict RHB, Smerbeck A, Parikh R, et al.Reliability and equivalence of alternate forms for the Symbol Digit Modalities Test: Implications for multiple sclerosis clinical trials. Mult Scler J. Epub ahead of print 2012. 10.1177/1352458511435717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barcellos LF, Bellesis KH, Shen L, et al. Remote assessment of verbal memory in MS patients using the California Verbal Learning Test. Mult Scler J 2018; 24: 354–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benedict RHB,Pol J,Yasin F, et al.Recovery of cognitive function after relapse in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Epub ahead of print 2020. 10.1177/1352458519898108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langdon D.A useful annual review of cognition in relapsing MS is beyon dmost neurologists - NO. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. Epub ahead of print 2016. 10.1177/1352458516640610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL,Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. Epub ahead of print 2001. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benedict RHB, Munschauer F,Linn R, et al. Screenin gformultipl esclerosis cognitive impairment using a self-administered 15-item questionnaire. Mult Scler. Epub ahead of print 2003. 10.1191/1352458503ms861oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.