Abstract

Sex-related differences can influence the outcomes of randomized clinical trials and may jeopardize the effectiveness of management and other therapeutics. Thus, it is essential to understand the mechanistic and translational aspects of sex differences in placebo outcomes. Recently, studies in healthy participants have shed light on how sex-related placebo effects might influence outcomes, yet no research has been conducted in a patient population. Herein, we used a tripartite approach to evaluate the interaction of prior therapeutic experience (eg, conditioning), expectations, and placebo effects in 280 chronic (orofacial) pain patients (215 women). In this cross-sectional study, we assessed sex differences in placebo effects, conditioning as a proxy of prior therapeutic effects, and expectations evaluated before and after the exposure to positive outcomes, taking into account participant–experimenter sex concordance and hormonal levels (estradiol and progesterone assessed in premenopausal women). We used mediation analysis to determine how conditioning strength and expectations impacted sex differences in placebo outcomes. Independent of gonadal hormone levels, women showed stronger placebo effects than men. We also found significant statistical sex differences in the conditioning strength and reinforced expectations whereby reinforced expectations mediated the sex-related placebo effects. In addition, the participant–experimenter sex concordance influenced conditioning strength, reinforced expectations, and placebo effects in women but not in men. Our findings suggest that women experience larger conditioning effects, expectations, and placebo effects emphasizing the need to consider sex as a biological variable when placebo components of any outcomes are part of drug development trials and in pain management.

Introduction

Illness is often sexually dimorphic, warranting unique management between women and men [65]. Globally, nearly 80% of chronic pain syndrome cases occur in women [65] while some psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia and autism are more common in men [3; 88]. In experimental pain studies reporting sex differences, women tend to be more sensitive to pain than men, with the largest differences observed in measures of heat, cold, and pressure pain tolerance [43; 66; 71]. Sexual dimorphism may jeopardize the effectiveness of pain management and other therapeutics [22; 51; 72; 86; 87]. Therefore, it is essential to understand the mechanistic and translational aspects of sex differences in placebo effects.

Placebo studies have emerged as a reliable means of exploring descending endogenous pain modulation [31]. Placebo effects can activate subcortical nuclei in the descending pain inhibitory system (rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) and periaqueductal gray (PAG)) and produce analgesic effects involving the release of endogenous opioids [85]. Although placebo hypoalgesia is one of the most frequently studied phenomena in the placebo field, knowledge regarding sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia is conflicting and scarce [35]. Early reviews and studies designed to elucidate biological and psychosocial determinants of placebo effects have yielded mixed results, reporting placebo hypoalgesia as greater in men [38; 83], greater in women, or equal in both sexes [38; 83]. Surprisingly little research has focused on the influence of sex as a biological variable on placebo effects. No studies have been done on sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia within a chronic pain population [7; 11].

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a disease that has been understudied despite the growing prevalence in young people [62; 76]. Moreover, TMD very often is associated with a variety of pain conditions including cervical pain, migraine, low back pain, irritable bowel syndromes, fibromyalgia, and therefore, has been recognized as a co-existing pain condition [61]. The general prevalence of TMD in the US population ranges from 5% to 12% [76] and disproportionately affects women [37; 78; 79].

Here, we explored sex-related effects on prior therapeutic experience (e.g. conditioning), as well as placebo effects in a cohort of participants with TMD. Use of classical conditioning to elicit placebo effects is commonplace and well-studied [54]. In this cross-sectional study, we used two distinct levels of individually-tailored painful stimuli (high and low pain) in a classical conditioning paradigm with the goal of reinforcing participants’ expectations of pain relief throughout a direct experience of hypoalgesia. In a testing phase, both levels of pain were surreptitiously set at a moderately high pain level to test for placebo effects. Using a tripartite approach, we determined the effects of sex as a biological variable on conditioning strength, expectations and placebo effects. Participant–experimenter sex concordance and female hormone levels (estradiol and progesterone) were taken into account. We also report data replicating previously published sex differences in clinical pain as well as experimental pain threshold and pain tolerance limits.

Methods

Study participants

Study participants were recruited locally through the University of Maryland, Baltimore and in the community via flyers, health fairs, and social media campaigns. A total of 285 TMD participants were recruited from August 2016 to May 2019. Four TMD participants met criteria of exclusion post-enrollment and were removed, with one excluded from analysis due to incomplete data. A total of 280 TMD participants were included in the analyses (Table 1). They were prescreened over the phone to determine potential eligibility before scheduling a clinical diagnostic appointment at the University of Maryland, School of Dentistry, Brotman Facial Pain Clinic, followed by one 3- to 4-hour experimental session at the University of Maryland, School of Nursing. TMD participants were therefore medically screened in person by a dental clinician to confirm a self-reported history of jaw, head, or facial pain for at least the prior three months and to determine the phenotypic classification and eligibility of their orofacial pain condition. Demographic, social-economic, and clinical factors for TMD participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of TMD study participants

| Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/Mean | SD/% | N/Mean | SD/% | p-value | |

| Sex | 65 | 23.2% | 215 | 76.8% | |

| Age Group | 0.798 | ||||

| 18–24 | 10 | 15.4% | 27 | 12.6% | |

| 25–44 | 24 | 36.9% | 94 | 43.7% | |

| 45–65 | 31 | 47.7% | 94 | 43.7% | |

| Education | 0.027* | ||||

| Completed high school | 13 | 20.0% | 26 | 12.1% | |

| Some college | 22 | 33.8% | 54 | 25.1% | |

| College graduate | 21 | 32.3% | 68 | 31.6% | |

| Professional or post-graduate degree | 9 | 13.8% | 67 | 31.2% | |

| Income | 0.131 | ||||

| $0–$19,999 | 20 | 30.8% | 52 | 24.2% | |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 13 | 20.0% | 44 | 20.5% | |

| $40,000–$59,999 | 12 | 18.5% | 26 | 12.1% | |

| $60,000–$79,999 | 5 | 7.7% | 24 | 11.2% | |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 9 | 13.8% | 23 | 10.7% | |

| $150,000 or higher | 5 | 7.7% | 25 | 11.6% | |

| Race | 0.025* | ||||

| Asian | 7 | 10.8% | 16 | 7.4% | |

| Black or African American | 32 | 49.2% | 67 | 31.2% | |

| White | 23 | 35.4% | 119 | 55.3% | |

| More than one race | 3 | 4.6% | 13 | 6.0% | |

| Ethnicity | 0.198 | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 | 3.1% | 13 | 6.0% | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 60 | 92.3% | 199 | 92.6% | |

| Unknown | 3 | 4.6% | 3 | 1.4% | |

| Weight (lbs) | 192.19 | 39.12 | 170.39 | 48.23 | <0.001*** |

| Height (in) | 69.92 | 2.57 | 64.77 | 2.93 | <0.001*** |

| Body Mass Index | 27.67 | 5.27 | 28.47 | 7.51 | 0.981 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 131.29 | 14.22 | 126.51 | 16.77 | 0.008** |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 81.37 | 11.53 | 79.42 | 9.10 | 0.207 |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 70.92 | 11.22 | 76.37 | 63.73 | 0.354 |

| Depressive symptoms (DASS) | 8.29 | 9.38 | 6.44 | 8.05 | 0.159 |

| Anxious symptoms (DASS) | 6.83 | 7.36 | 6.13 | 6.70 | 0.641 |

| Symptoms of stress (DASS) | 10.32 | 8.47 | 10.83 | 7.57 | 0.438 |

| GCPS Pain Intensity Score* | 40.43 | 23.35 | 50.11 | 21.80 | 0.002** |

| Duration of TMD-related pain (months) | 122.83 | 127.14 | 142.26 | 133.05 | 0.143 |

| GCPS Grade | 0.233 | ||||

| 0 | 2 | 3.1% | 5 | 2.3% | |

| I | 34 | 52.3% | 80 | 37.2% | |

| II | 9 | 13.8% | 48 | 22.3% | |

| III | 13 | 20.0% | 49 | 22.8% | |

| IV | 7 | 10.8% | 33 | 15.3% | |

| Pain Medicine | |||||

| NSAIDs | 15 | 23.1% | 57 | 26.5% | 0.579 |

| Muscle relaxants | 0 | 0% | 6 | 2.8% | 0.173 |

| BDZ | 1 | 1.5% | 14 | 6.5% | 0.119 |

| TCA | 0 | 0% | 4 | 1.9% | 0.268 |

| SSRI | 4 | 6.2% | 23 | 10.7% | 0.277 |

| SNRI | 0 | 0% | 19 | 8.8% | 0.013* |

| SARI | 1 | 1.5% | 8 | 3.7% | 0.382 |

| NDRI | 1 | 1.5% | 11 | 5.1% | 0.212 |

| Oxycodone | 5 | 9.6% | 9 | 4.7% | 0.175 |

| Vicodin | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0.5% | 0.602 |

| Morphine | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0.5% | 0.602 |

| Fentanyl | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0.5% | 0.602 |

| Percocet | 0 | 0% | 3 | 1.6% | 0.364 |

| Hydrocodone | 1 | 1.9% | 4 | 2.1% | 0.942 |

| Cocaine | 2 | 3.8% | 0 | 0% | 0.006** |

| Cannabis | 3 | 5.8% | 17 | 8.9% | 0.472 |

| Temperature in the conditioning phase | |||||

| Intensity of pain used (°C) Red | 46.97 | 2.27 | 46.46 | 2.24 | 0.032* |

| Intensity of pain used (°C) Green | 41.3 | 2.17 | 40.70 | 2.25 | 0.043* |

p ,0.05; † p ,0.01; ‡ p ,0.001.

The Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) assessment tool assists in the evaluation of chronic pain for use in general population surveys and studies of primary care pain patients.

Abbreviations: NSAIDs=Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs; BDZ=Benzodiazepine; TCA=Tricyclic antidepressants; SSRI=Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRI=Selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SARI=Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors; NDRI= Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor;

The study was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board (IRB, Protocol # HP-00068315). All methods were performed in in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and local guidelines and regulations for human research. A written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. The entire experimental session lasted approximately four hours, and participants were monetarily compensated for their time ($100).

Criteria of inclusion and exclusion

Participants who met the Diagnostic Criteria for TMDs (DC/TMD)75 and the following criteria were included in the study: 1. History positive for pain in the immediate 30 days prior to exam for both of the following: a. Pain in the jaw, temple, in the ear, or in front of the ear; and b. Pain modified with jaw movement, function, or parafunction; and 2. Exam positive for myalgia and/or arthralgia: a. Confirmation and duplication of pain location(s) in the temporalis, masseter, or other masticatory muscle(s); and/or (b) confirmation and duplication of pain in one or more temporomandibular joints.

TMD participants were excluded based on the following criteria: the presence of degenerative neuromuscular disease; cervical pain (e.g. stenosis or radiculopathy); a diagnosis of cardiovascular, neurological, kidney, or liver disease; pulmonary abnormalities; cancer within the past three years; color-blindness; or uncorrected impaired hearing. In addition to these criteria, individuals that were pregnant or breast-feeding were excluded from participating. A lifetime history of alcohol or drug dependence or a history of alcohol or drug abuse in the past year also excluded the individual from participating. Individuals with any severe psychiatric condition requiring medication (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, autism) or hospitalization in the last three years were excluded. Finally, the occurrence of facial trauma in previous 6 weeks or a history of severe facial trauma in the previous 2–3 months excluded the individual from participating.

Study design

Participants underwent the following protocols during the experimental paradigm: (1) a pain sensitivity assessment, and (2) conditioning and testing phases of the placebo procedure.

Pain sensitivity assessment.

Heat-thermal stimuli were delivered using the Pathway system (Medoc Advances Medical System, Rimat Yishai, Israel) whereby heat stimulations were administered starting at a temperature of 32°C and increasing at a rate of 1.0°C/s to a level that the participant signaled according to instruction, or a maximum temperature of 52°C. To determine the warmth and heat pain threshold, the heat increase rate was set at 0.3°C/s. Heat stimuli were delivered through a probe (30 X 30 mm ATS ATS thermode) held in place on the ventral surface of the participant’s dominant forearm. We assessed the individual pain sensitivity to tailor the level of high and low painful stimuli to each TMD participant using the Methods of Limits with the delivery of an ascending series of contact heat thermal stimuli [39; 69]. We therefore identified heat-warmth detection, heat-pain threshold, and heat-pain tolerance limits for each TMD participant. ‘Warmth detection’ was the minimum degrees Celsius temperature that each participant was able to feel warmth. ‘Painful threshold’ was the degrees Celsius temperature that each participant perceived as minimally painful. Finally, ‘painful tolerance limit’ was the maximum degrees Celsius temperature at which each TMD participant could no longer tolerate the heat-pain stimuli [33; 89].

Each modality was tested four times and participants were invited to press the Pathway remote button for each stimulus pertaining to each modality. An average temperature per sensitivity level was calculated to calibrate the pain modulation assessment. Each time the Pathway remote button was pressed, participants were also asked to confirm their reports verbally using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) from 0 to 100.

These values were used to set the intensities of heat-pain stimuli to be used during the conditioning phase. For example, pain was reported as 20 out of 100 (i.e. low pain) for four trials, (2) 50 out of 100 (i.e. medium pain) for four trials, and (3) 100 out of 100 (i.e. high pain) for four trials. The pain sensitivity assessment provided the average temperatures of maximum, moderate, and minimum levels of painful stimulations used for the subsequent conditioning phase and testing phase. Average temperatures used in conditioning phase and testing phase for each experimental group are reported in Table 1.

Placebo procedure: conditioning phase and testing phase.

Upon completion of the pain sensitivity assessment, participants were instructed about the experimental procedure. At this time, a sham electrode was attached just above the thermode on the participant’s arm and they were informed that the electrode, when active, would deliver a “sub-threshold electrical stimulus” that might be effective for pain reduction. Participants were informed the experimental procedure comprised a series of 36 trials during which painful stimuli would be delivered while the electrode was on (signaled by a green screen) or off (signaled by a red screen) (see Figure 1). Participants were informed that each visual cue would present for 10 seconds, during which the thermode would deliver a painful stimulus for 10 seconds and after which they would be asked to report their pain during that trial (0–100 VAS). The first 24 trials constituted the conditioning phase, during which temperature settings were lowered during green screen trials (6 °C lower than the maximum tolerance) and raised to pain tolerance during red screen trials (2 °C lower than the maximum tolerance). We further confirmed experimental settings by participants’ self-reported pain ratings to verify the temperatures approximately corresponding to 20 (green) and 80 (red) out of 100 on a VAS. Any difference in red-minus-green-associated pain reports during the conditioning phase was operationally defined as a ‘conditioning strength’ whereas the delta between red-minus green-associated pain reports during testing phase was operationally defined as ‘placebo hypoalgesia’ [10; 23; 24; 26].

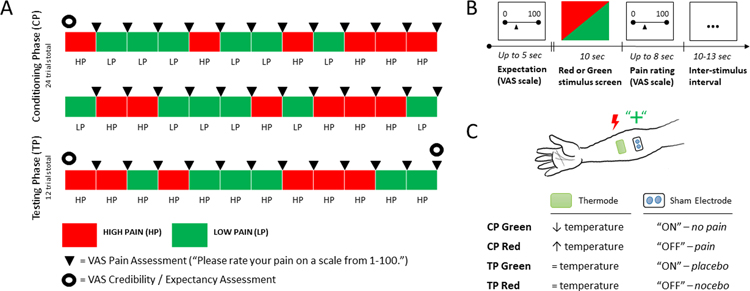

Fig. 1. Experimental paradigm for pain modulation and placebo analgesia.

(A) Overview of conditioning and testing phases of experiment. Placebo analgesia was measured through a testing phase of 12 heat-pain stimuli following a conditioning phase consisting of 24 heat-pain stimuli. A VAS pain assessment was administered after each trial in the conditioning and testing phase. Expectation was assessed verbally on a VAS scale before the conditioning phase, before the testing phase, and at the conclusion of the experiment. (B) Time course of single trial. Each red or green screen stimulus was presented for 10 seconds followed by an 8 second VAS pain rating exercise, concluding with a brief inter-stimulus interval of either 10 or 13 seconds (jitter). (C) Temperature manipulation during experiment. During the conditioning phase, red cues were associated with high-pain heat, while green cues were paired with low-pain heat through deliberate control of elevated temperature during red screens and reduced temperature during green screens. During the testing phase, we evaluated effects of condition by surreptitiously delivering the same temperature during both red and green cues. A VAS pain assessment was administered following each trial in conditioning phase and testing phase. A VAS expectation was also used to assess baseline, reinforced (post-conditioning) and post-test expectations.

Outcome expectation assessment.

Experimenters facilitated an assessment of baseline expectation (“Please rate your expectation about how well the electrode intervention will work”) before conditioning phase, an assessment of “reinforced expectations” before the testing phase (“Please rate how well you think the electrode intervention worked”) and efficacy of intervention after testing phase (“Please rate how well you think the electrode intervention worked this time”).

Personality assessment.

To examine the possible contribution of personality characteristics in explaining sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia, five dimensions of personality (i.e., Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness) were measured through NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) [27].

Hormonal and menstrual data acquisition

As part of female participants’ medical histories, data regarding menstrual cycle, including regularity of menses, date of last menstrual period, length of menses, length of bleeding, and birth control method, was collected (Table S1). To investigate the role of gonadal hormone levels, we calculated days since last menstruation and used this to calculate phase of the menstrual cycle at time of testing, whereby mid-follicular phase was defined as 4–8 days since last menstrual bleed and luteal phase was defined as 18–22 days since last menstrual bleed [34]. To confirm menstrual phase results for all pre-menopausal women in the TMD cohort (N=114), estradiol and progesterone were measured at the Institute for Clinical and Translational Research Core Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University using quantitative competitive ELISAs following the manufacturer’s protocol (ALPCO, Salem, NH). The estradiol assay had a sensitivity of 1.4 pg/ml, an intra-assay coefficient of variance of 6.97%, and an inter-assay coefficient of variance of 4.95%. The progesterone assay had a sensitivity of 0.1 ng/ml, an intra-assay coefficient of variance of 7.30%, and an inter-assay coefficient of variance of 8.72%. Each menstrual phase was biochemically defined in accordance with classifications put forth by Allen et al. (2016) [5]. One participant was excluded due to inconclusive test results.

During the experimental session, one experimenter was working with one participant. Four male experimenters (NRH, BD, LS, CO, mean age=29.33, SD=3.21) and eight female experimenters (TA, MB, CT, NC, NR, LC, ST, EO, mean age=30.86, SD=9.63) were included in the current study. All experimenters were trained by the Principle Investigator using standardized scripts and procedures across experimenters.

Male experimenters collected data from 57 participants with 40 women and 17 men, and female experimenters collected data from 223 participants including 175 women and 46 men. The sex distribution of participants between male experimenters (67.8% women, 32.2% men) and female experimenters (79.2% women, 20.8% men) was similar (Chi-square=3.39, p=0.066), allowing us to determine the participant-experimenter sex concordance’s impact on placebo hypoalgesia.

None of the experimenters was aware of the intention to determine the sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia throughout the experimental procedures. An independent staff member analyzed the data for the current study.

Statistical analysis

Power calculation. We performed a power analysis to determine the minimum number of participants for each cell required to assess sex differences. Given TMD showed higher prevalence in women than men [57], we calculated the statistical power based on unequal sample size between women and men at the allocation ratio of 3:1 [57]. Assuming a moderate effect size of sex differences on placebo hypoalgesia [24], we found a minimal sample size (N) of 280 (215 women and 65 men) would be sufficient to have 0.8 statistical power to observe a moderate sex difference effect size, Cohen’s d=0.4, at the alpha level of 0.05.

Sex differences in conditioning strength and placebo hypoalgesia, and expectations.

No missing data were reported from the participants for the current dataset. Given the unequal sample size of each cell, non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests and Kruskal-Wallis H tests were used to examine the differences in demographic and socioeconomic variables between sexes. Chronic pain severity, education, and race were treated as covariates for all analyses given sex differences were observed for those variables. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were also used to determine sex differences on expectation VAS ratings before conditioning phase and prior to testing phase, respectively. We first conducted an omnibus analysis using a Linear Mixed Model (LMM) to determine that both sexes had significant pain reduction experiences during the conditioning phase, and showed significant placebo analgesic effects during the testing phase. For the omnibus analysis, the VAS pain ratings for each of the trials were treated as the dependent variable while the color of the trials (red vs. green) and sex (women vs. men) were set as the fixed factors. LMM allowed us to compensate for any missing data and was superior to repeated measures ANOVA when dealing with unequal data structure [48]. Next, conditioning strength and placebo hypoalgesia were calculated as the difference between red- and green-associated pain ratings during the conditioning phase (for conditioning strength) and the testing phase (for placebo hypoalgesia). A total of twelve differences (deltas) were obtained from each participant during the conditioning phase, and six differences (delta) were obtained from each participant during the testing phase. A Linear Mixed Model (LMM) was adopted to explore sex differences in conditioning strength and placebo hypoalgesia, whereby the 12-repeated delta measures for each individual were treated as repeated variables for conditioning and the 6-repeated delta measures for each individual were treated as repeated variables for placebo. In addition to chronic pain severity, education and race, the level of heat-pain stimulation in °C during the conditioning phase and the testing phase were also treated as the covariates in the LMM models. Where significant interactions were observed, post-hoc analyses applying Bonferroni corrections were conducted. We calculated Cohen’s d to measure the effect size of placebo hypoalgesia [58]. For the most clinically relevant measures of placebo hypoalgesia, Number Needed to Treat (NNT) was computed using the conversion published by Furukawa and Leucht [40]. A r-to-z transformation test was used to compare the NNT differences between sexes.

We used mediation models to test the influences of pain reduction experiences during the conditioning phase (conditioning strength) and reinforced expectations in driving observed sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia. Sex (women vs. men) was set as the independent variable (X) while placebo hypoalgesia, computed as the average of red-minus-green delta scores of pain ratings during testing phase, was set as the dependent variable (Y). Conditioning strength and the VAS reinforced expectations were modeled as mediators in two separate analyses. Chronic pain severity, education, race and level of heat-pain stimulation used during the testing phase were treated as covariates in the mediation analyses. A bias-corrected bootstrapping method with 5000 times resampling was used to test for indirect effects. An indirect effect was considered to be significant when the 95% bootstrapped confidence interval (BCI) did not contain a zero. The mediation model was tested using the PROCESS macro in SPSS vers. 26 [46].

Conditioning strength and placebo hypoalgesia were slightly skewed based on Shapiro-Wilk test (p<0.001 for conditioning strength, p<0.001 for placebo hypoalgesia). Log transformation was then conducted for the main analyses.

Gonadal hormones and expectations, conditioning strength, and placebo hypoalgesia.

Estradiol and progesterone data from women who self-reported as pre-menopausal (N=114) were obtained. Bivariate correlations were first conducted to explore the associations between the two gonadal hormone levels and reinforced expectations, conditioning strength, and placebo hypoalgesia. We confirmed menstrual phase based on progesterone levels. Women with progesterone levels <2 ng/mL were considered as being in the follicular phase and women with progesterone levels >2 ng/mL were considered as being in luteal phase. A LMM approach was adopted with menstrual phase (luteal vs. follicular) set as a fixed factor to determine the menstrual phase differences in conditioning strength and placebo hypoalgesia.

Participant-experimenter sex effects in conditioning strength and placebo hypoalgesia.

Finally, we conducted additional LMMs to examine how participant sex and experimenter sex jointly influenced conditioning strength and magnitude of placebo hypoalgesia. The repeated delta scores of red-minus-green trials of pain ratings during conditioning phase and testing phase were treated as dependent variables, separately. Sex and participant-experimenter sex (same vs. different) were set as fixed factors.

All statistics were computed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA, vers. 26). The level of significance for all analyses was set at p≤0.05.

Results

Sex differences during the conditioning phase

We observed that all participants demonstrated significantly lower pain ratings for green trials compared to red trials over the course of 24 trials in the conditioning phase, as revealed by the significant main effect of the color of the trials (red vs. green, F1,3208.04=10747.72, p<0.001). Moreover, pair-wise comparisons within each sex indicated the pain ratings for green trials were significantly lower than that for red trials during the conditioning phase for both women (p<0.001) and men (p<0.001), suggesting successful learning in both women and men. The significant sex (women vs. men) by color of the trials (red vs. green) interaction (F1,3199.36=16.68, p<0.001) indicated that women had higher pain ratings for red trials (mean=68.29, sem=1.00, p=0.001) and lower pain ratings for green trials (mean=10.46, sem=0.67, p=0.003) compared to men (red: mean=65.49, sem=2.01; green: mean=11.29, sem=1.28, Figure 2A). Next, we operationalized the differences in red vs. green trials during the conditioning phase as the conditioning strength. We found that the conditioning strength was significantly greater in the last trial of conditioning phase (mean=60.766, sem=1.522) than the first (mean=48.814, sem=1.729, p<0.001). Women (mean=57.834, sem=0.436) exhibited greater conditioning strength as compared to men (mean=54.197, sem=0.793, F1,3230.00=6.06, p=0.014, Figure 2B).

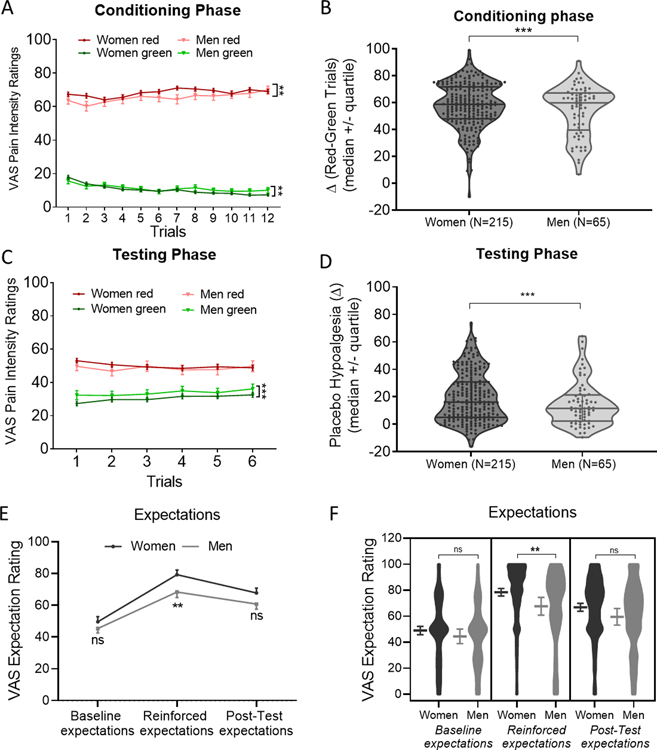

Fig. 2. Both men and women demonstrated learning in the conditioning phase and placebo hypoalgesia in testing phase, though stronger placebo effects were observed in women than men.

(A) Both women and men showed significant differences in pain ratings between red and green trials during conditioning phase (F1,3200.24=7353.62, p<0.001). The significant sex (women vs. men) by colors of the screens (red vs. green) interaction (F1,3199.36=16.68, p<0.001) indicated that women had higher pain ratings for red trials (p=0.001) and lower pain ratings for green trials (p=0.003) compared to men. (B) Delta scores of red-minus-green pain ratings during conditioning phase were presented for each participant. Women displayed significantly larger conditioning strength (pain ratings differences between red and green trials) than men (F1,3230.00=6.06, p=0.014). (C) The significant sex (women vs. men) by colors of the screens (red vs. green) interaction (F1,3007.91=8.41, p=0.004) indicated that women had significantly lower pain intensity ratings for green trials as compared to men (p=0.006). No sex differences in pain ratings were observed for red trials (p=0.279). (D) Delta scores of red-minus-green pain ratings during testing phase were presented for each participant. Women displayed significantly greater placebo hypoalgesia compared to men (F1,1613.49=10.50, p<0.001). (E) Time course of expectations between men and women. Data were presented in mean and SEM. (F) Women displayed significant greater reinforced expectations as compared to men. Women and men did not differ in expectations at baseline and post-testing phase. Data were presented in mean and SEM.

Sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia

For placebo effects (testing phase), both sexes showed evidence of placebo effects (F1,3004.63=520.13, p<0.001), though women (mean=19.4017, sem=0.612) exhibited larger placebo hypoalgesia than men (mean=14.794, sem=1.112, F1,1613.49=10.50, p<0.001, Figure 2C–D). Pair-wise comparisons applying Bonferroni corrections indicated that for both men and women, pain intensity ratings for green trials were significantly lower than red trials (men: p<0.001; women: p<0.001). This indicated that both sexes showed significant placebo hypoalgesia. More importantly, controlling for chronic pain severity, race, educational level, and heat-pain stimulations used in the testing phase, there was a significant sex (women vs. men) by color of the trials (red vs. green) interaction (F1,3007.91=8.41, p=0.004). For green trials, women showed significantly lower pain intensity ratings (mean=30.44, sem=0.59) than men (mean=33.51, sem=1.08, p=0.006), while no sex differences were found in pain ratings for red trials (women: 50.16, sem=0.62; men: mean=48.43, sem=1.13, p=0.279). This indicated that women showed significantly more pain relief for green conditions as compared to men. The sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia were independent from chronic pain severity, race, educational level, as well as the heat-pain stimulations used in the testing phase.”

In both sexes, placebo effects of the first trial of testing phase (mean = 21.524, SEM = 1.597) were significantly greater than the fourth (mean = 14.914, SEM = 1.524, P = 0.027). The remaining trials were not different in placebo effects from the second trial or from each other (all p’s>0.053). These results suggest that the magnitude of placebo effects gradually decreased over the testing phase but did not fully extinguish. There was no sex by trial interaction (F5,476.22=0.584, p=0.712), indicating no sex differences in placebo extinction patterns. We also calculated the number needed to be treated (NNT) within women and men, respectively [40]. The NNT for women (NNT=1.78) did not significantly differ from NNT for men (NNT=2.16, Z=−0.71, p=0.238).

Sex differences in expectations

Expectations regarding the efficacy of the (sham) device were assessed prior to conditioning and prior to testing (“On a scale from 0 to 100%, how likely do you believe this treatment intervention will work?” and “On a scale from 0 to 100%, how well do you believe this treatment worked?”). Though no difference in baseline expectation was observed between women (mean=49.60, sem=1.65) and men (mean=45.38, sem=2.83) at the beginning of the experimental session prior to conditioning (U=7735.500, p=0.182), women (mean=79.32, sem=1.48) reported higher reinforced expectations for treatment success prior to testing than men (mean=68.34, sem=3.44, U=8867.50, p=0.002, Cohen’s d=0.401). After the testing phase, participants rated the efficacy of intervention (“Please rate how well you think the electrode intervention worked this time“) and no significant sex differences in post-testing expectations were observed (U = 5939.5, P = 0.066, Figs. 2E and F).

Mediation approach

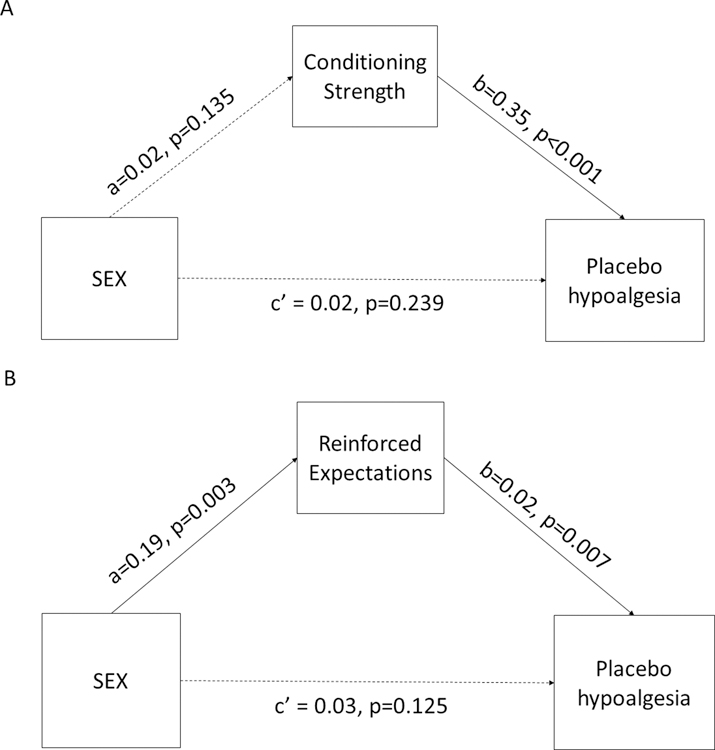

Using the mediation approach, we were able to statistically define the causal effects of prior pain reduction experiences during the conditioning phase (conditioning strength) as well as the role of reinfoced expectations in determining the sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia. Although conditioning strength was associated with greater placebo hypoalgesia (b=0.35, p<0.001), it did not drive the sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia observed (a*b=0.01, 95%BCI=−0.003 to 0.021, Figure 3A). Instead, reinforced expectations emerged as a significant mediator in determining the sex-related placebo effects (a*b=0.01, 95%BCI=0.002 to 0.025, Figure 3B).

Fig. 3. Mediation model of unconditioned response and reinforced expectation on placebo hypoalgesia.

(A) Although unconditioned response was associated with greater placebo hypoalgesia, it did not mediate the sex-related placebo effects. (B) Higher reinforced expectations drove greater placebo hypoalgesia in women as compared to men.

Role of gonadal hormones in sexually dimorphic placebo effects

To confirm menstrual phase of pre-menopausal women (n=114), we measured levels of estradiol and progesterone (Figure S1). We used these levels as a potential determinants of sex differences in conditioning strength, reinforced expectations, or placebo effects in pre-menopausal women as an explorative approach to elucidate whether the larger placebo effects observed in women were to some extent attributable to differences in hormone levels[34].

Neither estradiol level nor progesterone level was correlated with conditioning strength (estradiol: r=0.13, p=0.162; progesterone: r=0.05, p=0.567), reinforced expectation (estradiol: r=0.11 p=0.252; progesterone: r=0.07, p=0.485), or placebo effects (estradiol: r=−0.10, p=0.281; progesterone: r=−0.06, p=0.533). Interestingly, through an LMM approach, we found a significant main effect of menstrual phase on conditioning strength (F1,1253.99=7.70, p=0.006), with women in luteal phase (mean=63.52, sem=1.06) exhibiting greater conditioning strength than women in follicular phase (mean=60.68, sem=0.592, Cohen’s d=0.522). When comparing groups for placebo effects, however, no significant differences were observed (F1,662.45=0.294, p=0.588). Further, we found no differences in expectations prior to testing (p=0.983).

Role of participant-experimenter sex concordance in sexually dimorphic placebo effects

Previous evidence on the influence of experimenter sex on pain-related outcomes [81], led us to investigate whether or not any observed sexually dimorphic responses to placebo hypoalgesia were related to participant-experimenter sex concordance. Separate LMMs were conducted to determine participant-experimenter concordance’s impact on conditioning strength (12 delta scores of red-minus-green pain ratings during the conditioning phase) and placebo hypoalgesia (6 delta scores of red-minus-green pain ratings during the testing phase). For the LMMs, participant sex (women vs. men) and participant-experimenter sex concordance (same participant-experimenter sex vs. different participant-experimenter sex) were treated fixed factors. Race, educational level, chronic pain severity as well as temperature used during the conditioning/testing phases were treated as covariates.

We found a main effect of same participant-experimenter sex on conditioning strength (F1,3203.30=19.89, p<0.001), with a larger conditioning strength occurring when the sex of the experimenter and participant matched (e.g. man experimenter and man study participant). We also found a significant interaction between participant sex and participant-experimenter sex concordance (F1,3203.30=16.71, p<0.001) for conditioning strength. Further exploring this interaction within each sex, we found no significant effect of same participant-experimenter sex within the men cohort (p=0.811); rather, for women, those with an experimenter of the same sex (mean=61.458, sem=0.519) showed significantly greater conditioning strength than women with an experimenter of the opposite sex (mean=51.719, sem=1.602, p<0.001).

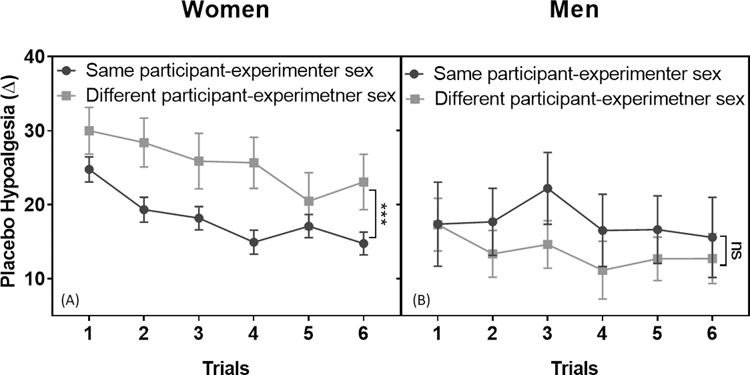

As far as placebo effects are concerned, we found no main effect of participant-experimenter sex concordance (F1,1611.94=1.02, p=0.312). There was, however, a significant interaction between sex and participant-experimenter sex concordance (F1,1611.94=11.32, p=0.001). Among men, no significant difference in placebo effects were found between those with a same-sex experimenter versus an opposite-sex experimenter (p=0.165). Among women, there was however, a significant difference (p<0.001) whereby women with a same-sex experimenter were less responsive (mean=18.067, sem=0.755) to placebo effects than women tested by an experimenter of the opposite sex (mean=25.021, sem=2.333, Figure 4A–B).

Fig. 4. Participant-experimenter sex concordance impact placebo hypoalgesia.

There was a significant participant sex and participant–experimenter sex concordance interaction in placebo hypoalgesia (F1,1611.94=11.32, p=0.001). (A) Post-hoc analyses applying Bonferroni corrections indicated that women with different sex experimenter showed greater placebo effects than women with same experimenter sex (p<0.001). (B) Participant-experimenter sex concordance did not influence placebo effects in men (p=0.165). The data were presented in mean and SEM.

For reinforced expectations, univariate ANCOVA with participant sex and participant-experimenter sex concordance revealed a significant interaction between sex and participant-experimenter sex concordance (F1,273=4.99, p=0.026). We also found significant differences based on participant-experimenter sex concordance within the female (p=0.009) but not the male cohort (p=0.088), whereby women with an experimenter of the same sex reported a higher expectation for treatment success than women with an experimenter of the opposite sex.

Sex differences in personality characteristics

In the current study, women scored higher in agreeableness as compared to men (t=4.18, p<0.001), but did not differ from men in terms of neuroticism (t=1.34, p=0.180), extraversion (t=1.74, p=0.084), openness (t=0.03, p=0.977) or conscientiousness (t=1.44, p=0.152). None of the 5 NEO personality traits were linked to the magnitude of placebo hypoalgesia in the current study (neuroticism: r=0.01, p=0.972; extraversion: r=0.10, p=0.104; openness: r=−0.05, p=0.389; agreeableness: r=−0.01, p=0.953; conscientiousness: r=−0.02, p=0.763), indicating that personality characteristics did not explain the sex differences in placebo hypoalgesia in the TMD participants.

Sex differences in clinical TMD pain and experimental pain threshold and tolerance limit

For sake of replicability, we tested sex differences in clinical TMD pain and experimental heat pain threshold and tolerance limits and confirmed that women were more sensitive to clinical (U=8757.00, p=0.002) and experimental (U=5389.500, p=0.005) pain (see Figure S2).

Discussion

The findings of this translational placebo-based study are three-fold. First, we demonstrated significant expectation-mediated sexual dimorphism in placebo hypoalgesia with larger sex-related placebo effects seen in women that was independent of individual chronic pain severity, pain sensitivity and personality characteristics. Second, in women, we observed a significant difference in the magnitude of placebo effects when women were paired with a same-sex experimenter versus an experimenter of the opposite sex with higher placebo effects being observed in the latter pairing. Third, we reproduced significant sex differences in experimental heat pain sensitivity whereby women exhibited lower pain threshold and tolerance limit than men. Though not a principle finding of this paper, we also echoed previous clinical chronic orofacial pain results indicating sexual dimorphism in severity of TMD.

Sex differences in placebo effects

We found robust sex effects on placebo responsiveness whereby women demonstrated greater unconditioned response (conditioning strength), higher levels of reinforced expectations and greater placebo effects than men. Previously, some preclinical studies have reported that men exhibit greater placebo effects than women [2; 4; 7; 8; 16], but opposite results have been also described [24; 45; 54; 56], and some have primarily enrolled men leaving no opportunity for comparison [44; 50]. A multitude of theories exist to explain sexual dimorphism in learning and conditioning, with the most popular hypotheses pertaining to brain development [29] and to memories, which are cyclically reinforced as experiences are accumulated [30]. Using a mediation model, we determined that reinforced expectation drove the sexual dimorphism observed in this cohort of TMD patients. Prior pain reduction experiences during the conditioning phase did not mediate the sex-related placebo effects. In line with another study [21], we found that unconditioned responses were associated with greater placebo effects in general, nonspecific to sex.

Notably, women and men did not show full extinction of the placebo effects and sex did not influence the extinction patterns. However, the current study only assessed placebo hypoalgesia within 30 minutes following classical conditioning. This short-term assessment may have impaired the capacity to observe the full extinction processes. Considering the translational relevance of the current findings for clinical trials, we computed the NNT for women and men separately. We found that the NNT for women did not show significant differences from NNT for men, indicating that both women and men may benefit equally from placebo effects in terms of NNT. Men’s and women’s NNTs were comparable to NNTs reported for pharmacological treatments (e.g. anticonvulsants and opioids - NNT from 1.7 to 3) for chronic pain patients [60]. Importantly, participant-experimenter sex concordance influenced unconditioned response (i.e., the response during the acquisition phase), expectations and placebo effects only in women but not in men. Although women in same participant-experimenter sex pairs displayed larger conditioning strength and higher expectation for treatment success, women with opposite sex experimenter showed greater placebo hypoalgesia. This work extends upon recent work in which our laboratory demonstrated that violation of expectations abolished placebo effects [25] and race concordance influenced both self-reported expectations and placebo effects [68].

Estradiol and progesterone influences in learning

Premenopausal women in the luteal and follicular phases did not show any significant differences in placebo effects. However, we found that premenopausal women in the luteal phase, when estradiol and progesterone are both high, exhibited significantly greater conditioning strength than premenopausal women in the follicular phase, when estradiol and progesterone are lower. Interestingly, rodent studies [41] have consistently reported that higher levels of estradiol and progesterone are associated with better Pavlovian learning in a fear extinction paradigm, where a previously conditioned stimuli (CS+) was paired with a ‘no adverse’ unconditional stimuli (no-US). This suggests a potential protective effect of estradiol and progesterone in improving CS+/no-US association. As with animal studies, human studies have also found that women in luteal phase displayed improved CS+/no-US association learning as compared to women in early follicular phase [6]. Brain imaging studies further revealed that higher estradiol is associated with greater brain activation in ventromedial frontal cortex [90], a region considered responsible for modulation of placebo effects via direct projections to the periaqueductal grey area [85]. In line with those previous findings, our results highlighted the important role of gonadal hormones in conditioning phase suggesting that higher estradiol and progesterone levels were associated with improved learning during conditioning. Yet, these hormonal variations, did not change expectations and placebo effects.

Sex differences in experimental and clinical pain

Women with TMD reported lower experimental pain threshold and heat-pain tolerance limits along with greater severity of orofacial pain than their male counterparts. Broadly, previous studies have demonstrated wide sex differences in pain perception, which can at least in part depend on sex-specific pain modulatory systems [53]. For example, specific factors such as vasopressin-receptor-regulator V1AR [67], k-opioid receptor function [19; 20], NMDA-mediated stress induced activity [49], morphine-induced activity[75], gonadal steroid hormones [28; 36; 42], parasympathetic activity [68], expectancy [80; 84] and empathy [64] have all been explored or implicated across studies on sex differences in pain. Here, we replicate findings from an early review on sex differences in pain by Fillingim et al. (2009) reporting a significant interaction between sex and pain threshold, as well as sex and pain tolerance [36]. Women showed increased sensitivity and decreased tolerance to heat pain stimuli in experimental settings compared to men. Differences between sexes in cases of TMD are well documented, with the burden of disease disproportionately affecting women in clinical settings at female-to-male ratios as high as 9:1 [78; 79]. Results from the OPPERA study also indicated that women experience greater clinical pain than men and show larger pain sensitivity [71], with sex-specific effects in genetic variants that affect clinical pain [13; 63].

Limitations

First, our study was conducted on chronic pain patients whose prior exposure to a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) was not assessed as an element that may have varied treatment expectations. Second, given that the sexual dimorphism may be related to sex effects on brain development, it is worth expanding the study population to a broader age range (children and the elderly). Future research should include pre-menstrual ages to discover at what point divergence in brain development begins to yield sexual dimorphism with an effect on placebo effects and descending pain modulation [12]. Lastly, when describing research subjects in a study on “sex difference”, it is important to appreciate a gendered spectrum of “maleness” and “femaleness” that we understand as a function of human biology, including gonadal hormone levels, in addition to social environment. The nuances of these differences are challenging to capture in the laboratory setting and we acknowledge a short-coming of this work lies in the narrow definition we’ve presented for men and women by biological self-reported “sex”. Future study on the female vs. male sociocultural environment and its shaping of self-reported pain (including an individual’s ability to express or talk about pain) is warranted [73].

Placebo effects, clinical trials, and translational value

Clinically, treatment outcomes are also modulated by positive prior experience [17; 18; 52; 59], which may be captured experimentally as conditioning strength in the laboratory setting [21]. A better understanding of how sex effects contribute to the difference between successful and unsuccessful learning is crucial to harness the full potential of conditioning and expectation as therapeutic tools in clinical practice. Placebo effects may be fostered by the words, attitudes, and procedures a clinician employs in their clinical practice. The importance of appropriate expectations for treatment outcomes have become an increasingly attention-gaining element of quality improvement initiatives, such that the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) has already funded over 50 comparative clinical effectiveness research studies related to shared decision making [1]. The impact of a patient’s expectations for change on their own physiology has been studied in the context of hormone secretion [13] and immune responses [81], in addition to specific clinical conditions such as pain [25], Parkinson’s disease [14; 32; 77], and depression [55; 74].

Our findings are the first of their kind to present a statistically significant relationship involving prior experience, reinforced expectations and placebo effects while controlling for the influence of female gonadal hormones and experimenter-participant sex concordance. Our cross-sectional study advances current knowledge in placebo science, adding to existing literature reporting sex differences in studies concerning placebo hypoalgesia in healthy participants [2; 4; 7; 8; 16]. In 2015, the National Institutes of Health (NIH; Bethesda MD, USA) mandated that all grant applications include sex as a biological variable in their experimental plan [47]. As an increasing number of studies incorporate this important advancement, we must remain vigilant about how we explore and explain sex differences in clinical trial outcomes. A rigorous understanding of sexual dimorphism in placebo effects is essential and we believe this work contributes the first of many complexities underlying how women may exhibit stronger placebo effects than their male counterparts, thus demonstrating the relevance of including sex as a factor that can influence the interpretation of trial results and clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank all the study participants for their time and cooperation with this research. We would like to thank Lieven Schenk, Brooks DuBose, Chika Okusogu, Christina Tricou, Nicole Corsi, Sharon Thomas, and Nandini Raghuraman for conducting part of the experiments.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Bethesda, MD, USA (grant # 1R01DE025946; PI: Colloca) and the University of Maryland School of Medicine Program for Research Initiated by Students and Mentors (PRISM, E.M. Olson). The views expressed here are the authors own and do not reflect the position or policy of the National Institutes of Health or any other part of the federal government.

Footnotes

Competing interests: E.O., Y.W., J.P., N.H., T.A., L.C., S.D., M.B., P.M. report no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: The dataset can be shared upon acceptance of this manuscript by contacting the corresponding author.

References and Notes:

- [1].Research spotlight on shared decision making. In: P-COR Institute editor. Topic Spotlight: Shared Decision Making, 2019. Available at: https://wwwpcoriorg/topics/shared-decision-making.

- [2].Abrams K, Kushner MG. The moderating effects of tension-reduction alcohol outcome expectancies on placebo responding in individuals with social phobia. Addict Behav 2004;29(6):1221–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Aleman A, Kahn RS, Selten JP. Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: evidence from meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(6):565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Aletky PJ, Carlin AS. Sex differences and placebo effects: motivation as an intervening variable. J Consult Clin Psychol 1975;43(2):278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Allen AM, McRae-Clark AL, Carlson S, Saladin ME, Gray KM, Wetherington CL, McKee SA, Allen SS. Determining menstrual phase in human biobehavioral research: A review with recommendations. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2016;24(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Antov MI, Stockhorst U. Stress exposure prior to fear acquisition interacts with estradiol status to alter recall of fear extinction in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014;49:106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Aslaksen PM, Bystad M, Vambheim SM, Flaten MA. Gender differences in placebo analgesia: event-related potentials and emotional modulation. Psychosom Med 2011;73(2):193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Aslaksen PM, Flaten MA. The roles of physiological and subjective stress in the effectiveness of a placebo on experimentally induced pain. Psychosom Med 2008;70(7):811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Atlas LY, Wager TD. How expectations shape pain. Neuroscience Letters 2012;520(2):140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Au Yeung ST, Colagiuri B, Lovibond PF, Colloca L. Partial reinforcement, extinction, and placebo analgesia. Pain 2014;155(6):1110–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Averbuch M, Katzper M. Gender and the placebo analgesic effect in acute pain. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 2001;70(3):287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bale TL. Sex matters. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019;44(1):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Belfer I, Segall SK, Lariviere WR, Smith SB, Dai F, Slade GD, Rashid NU, Mogil JS, Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Liu Q, Bair E, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. Pain modality- and sex-specific effects of COMT genetic functional variants. Pain 2013;154(8):1368–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Benedetti F, Colloca L, Torre E, Lanotte M, Melcarne A, Pesare M, Bergamasco B, Lopiano L. Placebo-responsive Parkinson patients show decreased activity in single neurons of subthalamic nucleus. Nat Neurosci 2004;7(6):587–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Benedetti F, Pollo A, Lopiano L, Lanotte M, Vighetti S, Rainero I. Conscious Expectation and Unconscious Conditioning in Analgesic, Motor, and Hormonal Placebo/Nocebo Responses. The Journal of Neuroscience 2003;23(10):4315–4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bjorkedal E, Flaten MA. Interaction between expectancies and drug effects: an experimental investigation of placebo analgesia with caffeine as an active placebo. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;215(3):537–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bjorkedal E, Flaten MA. Expectations of increased and decreased pain explain the effect of conditioned pain modulation in females. J Pain Res 2012;5:289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Butcher BE, Carmody JJ. Sex differences in analgesic response to ibuprofen are influenced by expectancy: a randomized, crossover, balanced placebo-designed study. European journal of pain (London, England) 2012;16(7):1005–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chakrabarti S, Liu NJ, Gintzler AR. Formation of mu-/kappa-opioid receptor heterodimer is sex-dependent and mediates female-specific opioid analgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107(46):20115–20119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Clemente JT, Parada CA, Veiga MC, Gear RW, Tambeli CH. Sexual dimorphism in the antinociception mediated by kappa opioid receptors in the rat temporomandibular joint. Neurosci Lett 2004;372(3):250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Colloca L, Akintola T, Haycock NR, Blasini M, Thomas S, Phillips J, Corsi N, Schenk L, Wang Y. Prior therapeutic experiences, not expectation ratings, predict placebo effects: an experimental study in chronic pain and healthy participants. Psychother Psychosom 2020; 10.1159/000507400 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [22].Colloca L, Barsky AJ. Placebo and Nocebo Effects. N Engl J Med 2020;382(6):554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Colloca L, Benedetti F. How prior experience shapes placebo analgesia. Pain 2006;124(1–2):126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Colloca L, Pine DS, Ernst M, Miller FG, Grillon C. Vasopressin Boosts Placebo Analgesic Effects in Women: A Randomized Trial. Biol Psychiatry 2016;79(10):794–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Colloca L, Schenk LA, Nathan DE, Robinson OJ, Grillon C. When expectancies are violated: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2019;106(6):1246–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Colloca L, Tinazzi M, Recchia S, Le Pera D, Fiaschi A, Benedetti F, Valeriani M. Learning potentiates neurophysiological and behavioral placebo analgesic responses. Pain 2008;139(2):306–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Costa PT Jr, McCrae RR. The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO- PI-R): Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Craft RM, Mogil JS, Aloisi AM. Sex differences in pain and analgesia: the role of gonadal hormones. European journal of pain (London, England) 2004;8(5):397–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dalla C, Shors TJ. Sex differences in learning processes of classical and operant conditioning. Physiol Behav 2009;97(2):229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dalla C, Shors TJ. Sex differences in learning processes of classical and operant conditioning. Physiology & Behavior 2009;97(2):229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Damien J, Colloca L, Bellei-Rodriguez CE, Marchand S. Pain Modulation: From Conditioned Pain Modulation to Placebo and Nocebo Effects in Experimental and Clinical Pain. Int Rev Neurobiol 2018;139:255–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].de la Fuente-Fernandez R, Ruth TJ, Sossi V, Schulzer M, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ. Expectation and dopamine release: mechanism of the placebo effect in Parkinson’s disease. Science 2001;293(5532):1164–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Defrin R, Ohry A, Blumen N, Urca G. Sensory determinants of thermal pain. Brain 2002;125(Pt 3):501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dreher JC, Schmidt PJ, Kohn P, Furman D, Rubinow D, Berman KF. Menstrual cycle phase modulates reward-related neural function in women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104(7):2465–2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Enck P, Klosterhalfen S. Does Sex/Gender Play a Role in Placebo and Nocebo Effects? Conflicting Evidence From Clinical Trials and Experimental Studies. Front Neurosci 2019;13:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL 3rd. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society 2009;10(5):447–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Fillingim RB, Slade GD, Diatchenko L, Dubner R, Greenspan JD, Knott C, Ohrbach R, Maixner W. Summary of findings from the OPPERA baseline case-control study: implications and future directions. J Pain 2011;12(11 Suppl):T102–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Franconi F, Campesi I, Occhioni S, Antonini P, Murphy MF. Sex and gender in adverse drug events, addiction, and placebo. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2012;214:107–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fruhstorfer H, Lindblom U, Schmidt WC. Method for quantitative estimation of thermal thresholds in patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1976;39(11):1071–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Furukawa TA, Leucht S. How to obtain NNT from Cohen’s d: comparison of two methods. PloS one 2011;6(4):e19070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Garcia NM, Walker RS, Zoellner LA. Estrogen, progesterone, and the menstrual cycle: A systematic review of fear learning, intrusive memories, and PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev 2018;66:80–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Greenspan JD, Craft RM, LeResche L, Arendt-Nielsen L, Berkley KJ, Fillingim RB, Gold MS, Holdcroft A, Lautenbacher S, Mayer EA, Mogil JS, Murphy AZ, Traub RJ, Consensus Working Group of the Sex G, Pain SIGotI. Studying sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia: a consensus report. Pain 2007;132 Suppl 1:S26–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Greenspan JD, Traub RJ. Gender differences in pain and its relief In: McMahon S, Klotzenburg M, Tracey I, Turk DC, editors. Wall & Melzack’s Textbook of Pain: Expert Consult - Online and Print. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013. pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hadamitzky M, Sondermann W, Benson S, Schedlowski M. Placebo Effects in the Immune System. Int Rev Neurobiol 2018;138:39–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Haltia LT, Rinne JO, Helin S, Parkkola R, Nagren K, Kaasinen V. Effects of intravenous placebo with glucose expectation on human basal ganglia dopaminergic function. Synapse 2008;62(9):682–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford publications, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [47].National Institutes of Health. Inclusion of women and minorities as participants in research involving human subjects—policy implementation page. National Institutes of Health: Grants & Funding; 2018. Available at: https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities.htm. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hesselmann G Applying linear mixed effects models (LMMs) in within- participant designs with subjective trial-based assessments of awareness-a caveat. Front Psychol 2018;9:788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ivkovic N, Racic M, Lecic R, Bozovic D, Kulic M. Relationship Between Symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders and Estrogen Levels in Women With Different Menstrual Status. Journal of oral & facial pain and headache 2018;32(2):151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Keller A, Akintola T, Colloca L. Placebo Analgesia in Rodents: Current and Future Research. Int Rev Neurobiol 2018;138:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Keogh E, McCracken LM, Eccleston C. Do men and women differ in their response to interdisciplinary chronic pain management? Pain 2005;114(1–2):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kessner S, Wiech K, Forkmann K, Ploner M, Bingel U. The effect of treatment history on therapeutic outcome: an experimental approach. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(15):1468–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Khan HS, Stroman PW. Inter-individual differences in pain processing investigated by functional magnetic resonance imaging of the brainstem and spinal cord. Neuroscience 2015;307:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Klosterhalfen S, Kellermann S, Braun S, Kowalski A, Schrauth M, Zipfel S, Enck P. Gender and the nocebo response following conditioning and expectancy. J Psychosom Res 2009;66(4):323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Krimmel SR, Zanos P, Georgiou P, Colloca L, Gould TD. Classical conditioning of antidepressant placebo effects in mice. Psychopharmacology 2020;237:93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Krummenacher P, Kossowsky J, Schwarz C, Brugger P, Kelley JM, Meyer A, Gaab J. Expectancy-induced placebo analgesia in children and the role of magical thinking. J Pain 2014;15(12):1282–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Landi N, Lombardi I, Manfredini D, Casarosa E, Biondi K, Gabbanini M, Bosco M. Sexual hormone serum levels and temporomandibular disorders. A preliminary study. Gynecol Endocrinol 2005;20(2):99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Lenhard WL, A. Hypothesis Tests for Comparing Correlations. Bibergau (Germany): Psychometrica, 2014.

- [59].Lorber W, Mazzoni G, Kirsch I. Illness by suggestion: expectancy, modeling, and gender in the production of psychosomatic symptoms. Ann Behav Med 2007;33(1):112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lynch ME, Watson CP. The pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a review. Pain Res Manag 2006;11(1):11–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA, Smith SB, Slade GD. Overlapping Chronic Pain Conditions: Implications for Diagnosis and Classification. J Pain 2016;17(9 Suppl):T93–T107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Mazzetto MO, Rodrigues CA, Magri LV, Melchior MO, Paiva G. Severity of TMD related to age, sex and electromyographic analysis. Braz Dent J 2014;25(1):54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Meloto CB, Bortsov AV, Bair E, Helgeson E, Ostrom C, Smith SB, Dubner R, Slade GD, Fillingim RB, Greenspan JD, Ohrbach R, Maixner W, McLean SA, Diatchenko L. Modification of COMT-dependent pain sensitivity by psychological stress and sex. Pain 2016;157(4):858–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Mikosz M, Nowak A, Werka T, Knapska E. Sex differences in social modulation of learning in rats. Sci Rep 2015;5:18114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Mogil JS. Sex differences in pain and pain inhibition: multiple explanations of a controversial phenomenon. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012;13(12):859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Mogil JS, Bailey AL. Sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia. Progress in brain research 2010;186:141–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Mogil JS, Sorge RE, LaCroix-Fralish ML, Smith SB, Fortin A, Sotocinal SG, Ritchie J, Austin JS, Schorscher-Petcu A, Melmed K, Czerminski J, Bittong RA, Mokris JB, Neubert JK, Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Campbell JN, Crawley JN, Lariviere WR, Wallace MR, Sternberg WF, Balaban CD, Belfer I, Fillingim RB. Pain sensitivity and vasopressin analgesia are mediated by a gene-sex-environment interaction. Nat Neurosci 2011;14(12):1569–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Nahman-Averbuch H, Dayan L, Sprecher E, Hochberg U, Brill S, Yarnitsky D, Jacob G. Sex differences in the relationships between parasympathetic activity and pain modulation. Physiol Behav 2016;154:40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Nielsen CS, Price DD, Vassend O, Stubhaug A, Harris JR. Characterizing individual differences in heat-pain sensitivity. Pain 2005;119(1–3):65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Okusogu C, Wang Y, Akintola T, Haycock NR, Raghuraman N, Greenspan JD, Phillips J, Dorsey SG, Campbell CM, Colloca L. Placebo hypoalgesia: racial differences. PAIN 2020;161:1872–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Ostrom C, Bair E, Maixner W, Dubner R, Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Slade GD, Greenspan JD. Demographic Predictors of Pain Sensitivity: Results From the OPPERA Study. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society 2017;18(3):295–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Pieh C, Altmeppen J, Neumeier S, Loew T, Angerer M, Lahmann C. Gender differences in outcomes of a multimodal pain management program. Pain 2012;153(1):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Robinson ME, Riley JL 3rd, Myers CD, Papas RK, Wise EA, Waxenberg LB, Fillingim RB. Gender role expectations of pain: relationship to sex differences in pain. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society 2001;2(5):251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Rutherford BR, Wall MM, Brown PJ, Choo TH, Wager TD, Peterson BS, Chung S, Kirsch I, Roose SP. Patient Expectancy as a Mediator of Placebo Effects in Antidepressant Clinical Trials. Am J Psychiatry 2017;174(2):135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Saloman JL, Niu KY, Ro JY. Activation of peripheral delta-opioid receptors leads to anti-hyperalgesic responses in the masseter muscle of male and female rats. Neuroscience 2011;190:379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP, List T, Svensson P, Gonzalez Y, Lobbezoo F, Michelotti A, Brooks SL, Ceusters W, Drangsholt M, Ettlin D, Gaul C, Goldberg LJ, Haythornthwaite JA, Hollender L, Jensen R, John MT, De Laat A, de Leeuw R, Maixner W, van der Meulen M, Murray GM, Nixdorf DR, Palla S, Petersson A, Pionchon P, Smith B, Visscher CM, Zakrzewska J, Dworkin SF, International Rdc/Tmd Consortium Network IafDR, Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group IAftSoP. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Groupdagger. Journal of oral & facial pain and headache 2014;28(1):6–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Schmidt L, Braun EK, Wager TD, Shohamy D. Mind matters: placebo enhances reward learning in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci 2014;17(12):1793–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Scrivani SJ, Keith DA, Kaban LB. Temporomandibular disorders. The New England journal of medicine 2008;359(25):2693–2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Shaefer JR, Khawaja SN, Bavia PF. Sex, Gender, and Orofacial Pain. Dental clinics of North America 2018;62(4):665–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Smith YR, Stohler CS, Nichols TE, Bueller JA, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Pronociceptive and antinociceptive effects of estradiol through endogenous opioid neurotransmission in women. J Neurosci 2006;26(21):5777–5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Sorge RE, Martin LJ, Isbester KA, Sotocinal SG, Rosen S, Tuttle AH, Wieskopf JS, Acland EL, Dokova A, Kadoura B, Leger P, Mapplebeck JC, McPhail M, Delaney A, Wigerblad G, Schumann AP, Quinn T, Frasnelli J, Svensson CI, Sternberg WF, Mogil JS. Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents. Nat Methods 2014;11(6):629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Tekampe J, van Middendorp H, Sweep F, Roerink S, Hermus A, Evers AWM. Human Pharmacological Conditioning of the Immune and Endocrine System: Challenges and Opportunities. Int Rev Neurobiol 2018;138:61–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Vambheim SM, Flaten MA. A systematic review of sex differences in the placebo and the nocebo effect. J Pain Res 2017;10:1831–1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].van Wijk G, Veldhuijzen DS. Perspective on diffuse noxious inhibitory controls as a model of endogenous pain modulation in clinical pain syndromes. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society 2010;11(5):408–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Wager TD, Atlas LY. The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015;16(7):403–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Weimer K, Colloca L, Enck P. Age and sex as moderators of the placebo response - an evaluation of systematic reviews and meta-analyses across medicine. Gerontology 2015;61(2):97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Weimer K, Colloca L, Enck P. Placebo eff ects in psychiatry: mediators and moderators. Lancet Psychiatry 2015;2(3):246–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Werling DM, Geschwind DH. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Neurol 2013;26(2):146–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Yarnitsky D, Ochoa JL. Studies of heat pain sensation in man: perception thresholds, rate of stimulus rise and reaction time. Pain 1990;40(1):85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Zeidan MA, Igoe SA, Linnman C, Vitalo A, Levine JB, Klibanski A, Goldstein JM, Milad MR. Estradiol modulates medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala activity during fear extinction in women and female rats. Biol Psychiatry 2011;70(10):920–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.