Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this retrospective study was to describe the efficacy of management of bisphosphonate-related maxillary osteonecrosis, which had resulted in an oroantral fistula formation, by performing sequestrectomy, platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and buccal fat pad (BFP) flap.

Patient and Methods

A total of 7 patients diagnosed with stage III maxillary medication-related osteonecrosis according to guidelines of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. All patients complained of persistent pain, swelling and purulent drainage with sinusitis. In order to keep the infection under control, the patients first received an antibiotic combination for 2 weeks. Then, sequestrectomy and bone debridement were performed under general anesthesia. After that, an antrectomy was performed via endoscopic sinus surgery in some cases. And the fistula was closed with BFP after or before the PRF application to the region depending on the size of the fistula.

Results

The fistula was successfully closed. After a mean follow-up of 16 months, no symptoms were seen in the patients.

Conclusions

The patients were successfully managed with a combined treatment consisted of sequestrectomy, PRF and BFP. We suggest that large defects arose from medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw can be managed with such a combined approach in order to lessen the recurrence risk.

Keywords: Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, Bisphosphonates, Oroantral fistula, Sequestrectomy, Buccal fat pad, Platelet-rich fibrin

Introduction

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) is defined as the necrosis occurring in the jaw bone depending on the prolonged use of anti-resorptive and anti-angiogenic medications [1]. For the diagnosis of MRONJ in any patient, the presence of the following criteria is required:

A positive history of anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic agents intake,

Exposed bone or bone that can be probed through an intraoral or extraoral fistula in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for longer than 8 weeks,

No history of radiation therapy in the head and neck region,

No evidence of metastatic disease involving the jaws [1].

Especially, intravenous bisphosphonates (BPs) are widely used as anti-resorptive medications in the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy, osseous metastases of solid tumors such as breast, prostate, lung cancers and management of multiple myeloma containing bone involvement. The oral BPs are commonly used in osteoporosis and osteopenia patients and the mandible is more frequently affected by MRONJ than the maxilla [2, 3]. In advanced cases seen in the maxilla, there is usually diagnosed maxillary sinusitis and an oroantral fistula accompanying it [4, 5]. In these cases, patients complain about pain, swelling and halitosis. Treatment of MRONJ is variable depending on stage. Surgical intervention is recommended in advanced stages such as stages 2 and 3 [1].

The defects that occur after surgery or oroantral communications are usually covered by the local mucosal flap. But it does not provide sufficient coverage in large defects due to the limited size. In such cases, the buccal fat pad (BFP) is also preferred because of vascularity supply and abundantly available (6). As far as we know, BFP flap was first described by Egyedi in 1977 for the closure of oroantral and oronasal communications [7]. Recently, successful closure of oroantral fistulae with BFP is widely reported in the literature [6, 8]. But few cases were reported in the literature about the use of BFP in the management of oral defects after medical related osteonecrosis of the maxilla [9, 10].

Wound healing is a process mediated by various signaling molecules and growth factors. Growth factors in autologous platelets are of great importance in accelerating wound healing [11]. The efficacy of improved wound healing stems from the ability of the wound to continuously release various growth factors throughout the healing process [12]. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) has been shown to stimulate wound healing by collecting cells such as osteoblasts, endothelial cells, chondrocytes and fibroblasts [11]. These specialized cells play a role in wound healing and angiogenesis. As the dissolution of the fibrin matrix is slow, it provides a large part of the factors involved in PRF angiogenesis and neocollagenesis until the 7th day of wound healing [13]. PRF also contains a significant amount of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) that stimulates epithelial healing, tissue vascularizationand soft tissue regeneration [14].

Here we report case series of large defect containing both of oroantral and oronasal fistula caused by medication-related osteonecrosis. Combined techniques with buccal fat pad and PRF consisting of sequestrectomy were performed in these cases.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee of the University. In this study, all the patients (N = 07) affected by stage III posterior maxillary medication-related osteonecrosis presented with sinusitis maxillaris. In 5 cases BPs had been administered for carcinoma and 2 cases for osteoporosis (Table 1). In all cases, intraoral examination revealed swelling, mucosal ulceration, infection and bone exposure (Fig. 1). After clinical examination, maxillofacial computed tomography and medical and oncologic assessment, the patients were treated with sequestrectomy, bone debridement and reconstruction using a BFP and PRF.

Table 1.

Patients included in the case series

| Patient ID | Age | Gender | Bisphosphonate | Dose | PI | Follow-up (m) | Cmps | Antrectomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KT | 73 | Male | Zoledronate | 4 mg/5 mL (iv) | Prostate CA | 18 | swd | + |

| ZB | 50 | Female | Zoledronate | 4 mg/5 mL (iv) | Breast CA | 18 | − | – |

| BC | 54 | Female | Ibandronate | 150 mg (oral) | Breast CA | 12 | − | − |

| HA | 65 | Female | Zoledronate | 4 mg/5 mL (iv) | Breast CA | 18 | − | + |

| SC | 66 | Female | Ibadronate | 150 mg (oral) | Osteoporosis | 12 | − | − |

| AK | 72 | Female | Risedronate | 5 mg (oral) | Osteoporosis | 12 | − | − |

| MU | 73 | Female | Zoledronate | 4 mg/5 mL (iv) | Breast CA | 12 | swd | − |

PI primary indication, m month, Cmps complications, swd small wound dehiscence

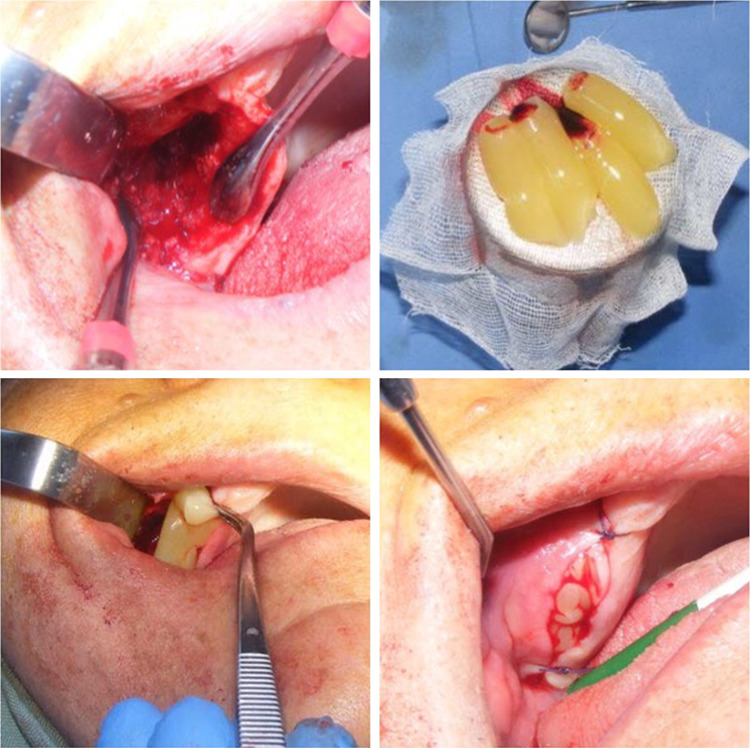

Fig. 1.

Intraoral view of the patient revealed that swelling, mucosal ulceration, infection and bone exposure

Before the surgery medical therapy was applied to all patients with amoxicillin–clavulanate (2 g/day) and ornidazole (1 g/day) for 2 weeks. Mouthwashes with chlorhexidine gluconate were also prescribed. Then, sequestrectomy and bone debridement were performed under general anesthesia (Fig. 2). After that, an antrectomy was performed via endoscopic sinus surgery by otolaryngologists in order to examine the status of the osteomeatal complex in 2 cases. The obstruction of osteomeatal complex was opened to allow air flow to the sinus. After the maxillary sinus was abundantly irrigated with saline solution orally, an incision was made in the superior vestibular sulcus about 8–10 mm from the level of the upper second molar to the second premolar, exposing the maxillary periosteum and the buccal fat pad. Careful manipulation and blunt dissection were carried out to mobilize and advance the flap to the maxillary defect.

Fig. 2.

Sequestrotomy and curettage were performed first

The protocol described by Dohan et al. [15] for the PRF preparation was considered. Preoperatively, 20 mL of venous blood was drawn and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to prepare PRF in the machine (DUO® Quattro Centrifuge) (Fig. 3). In this procedure, 10 mL tubes without anticoagulants were used. The prepared PRF was placed under BFP in patients who had small oroantral fistula and adequate bone cavity (Fig. 4). On the other hand, the PRF was placed in the form of membranes over the BFP in patients who had large oroantral fistulas and unfavorable bone cavity (Fig. 5). The overlying mucosa was sutured over the fat pad tension-free flap closure was achieved (Figs. 6, 7). Antibiotic treatment (amoxicillin–clavulanate) was continued for the 5 days following surgery. The antral triad of decongestants, antihistamines and analgesics was prescribed for 5 days. After 2 weeks, 2–3 mm wound dehiscence was seen in some of the patients. But completely closed was achieved in 1 month with repeated irrigations. No dehiscence, infection or necrosis was observed. No new oroantral communication was observed after an average of 18-month follow-up (Fig. 8).

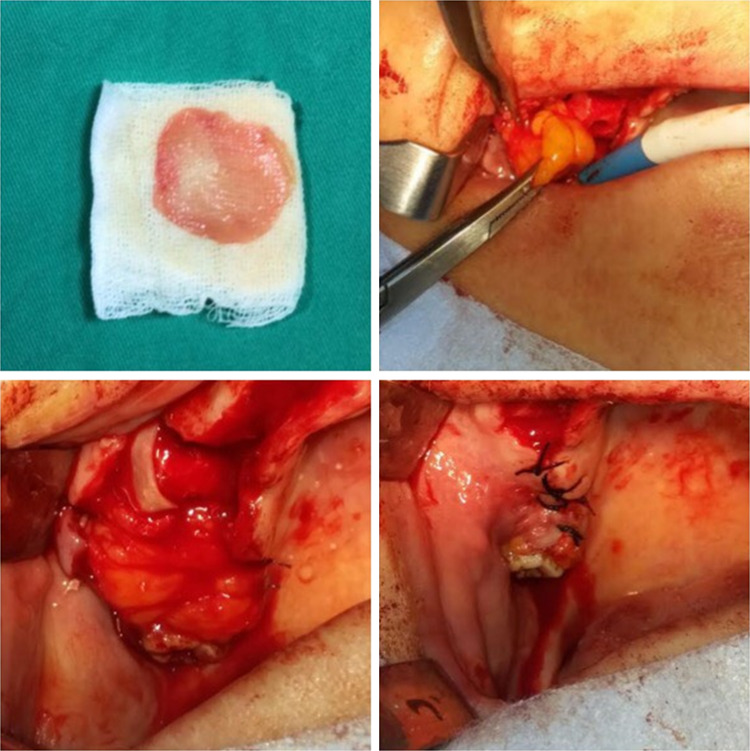

Fig. 3.

Centrifuge machine used in the study is seen. (DUO® Quattro Centrifuge)

Fig. 4.

Otained PRFs were placed in the region by forceps and adapted to the cavity with a sponge. Then, the BFP was covered and the region was primarily closed with sutures

Fig. 5.

In cases with insufficient bone cavity, the PRFs were formed into a membrane and adapted to cover the BFP. And then, the mucosa was sutured

Fig. 6.

Buccal fat tissue was extended on the cavity

Fig. 7.

In this case, because the bone cavity was insufficient, PRF was applied as a membrane. The overlying mucosa was sutured over the fat pad tension-free flap closure was achieved

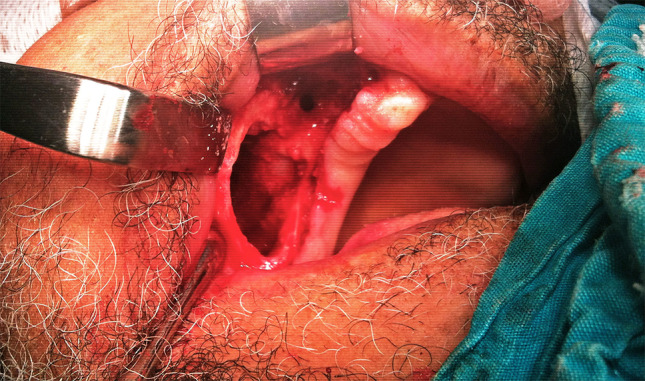

Fig. 8.

No new oroantral communication was observed after an average of 18-month follow-up

Discussion

The first definitions of MRONJ were reported in 2003 by several authors [16–18]. But, why the anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic medications cause osteonecrosis in the jaw bone and pathogenesis of this condition is poorly understood so far. However, some theories have been suggested include altered bone remodeling or over suppression of bone resorption, inhibition of angiogenesis, soft tissue toxicity, inflammation or infection [19]. Recently, Otto et al. suggest a theory that local infections and infection-related pH changes play an important role in the pathogenesis of MRONJ [20]. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates are released and activated in the acidic environment [21]. Because of the alveolar bone which is most prone to infections this situation may explain why the MRONJ are seen in the jaw bones. The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons also reported that although tooth extraction was performed in most initial reported cases of osteonecrosis of jaws, and these teeth commonly had the existing periodontal or periapical disease [1]. In our case, the patient presented a history of mobile teeth in the same region before 2 years. So, we suggest that a periodontal infection could have triggered the MRONJ.

In the clinical and radiological examination, if exposed necrotic bone extending beyond the region of alveolar bone such as maxillary sinus and resulting in oroantral or oronasal communication, these clinical conditions are defined stage III. Treatment strategies include antibacterial mouth rinse, antibiotic therapy and surgical debridement or resection [1]. In a multicenter study [4], clinically active maxillary sinusitis was found 43.6% (23 patients) in the 53 cases of maxillary MRONJ. And an oroantral fistula was detected in 35.8% (19/53). The authors did not give detailed information about the treatment methods in the oroantral fistula cases. In another clinical study [5], 10 patients diagnosed with stage III MRONJ presented with concomitant sinusitis maxillaris and eight of the ten patients underwent an antrectomy. The defect was closed with a local mucosal flap in seven cases and with a BFP in one case. The authors reported recurrences in four cases. But the authors did not mention any oroantral fistula in their article. Few studies are outstanding in the literature about the treatment of bone defects caused by MRONJ with BFP [9, 10]. However, there is no mention of the treatment of large oroantral fistula with BFP in these clinical cases.

The osteomeatal complex (OMC), including the ostium of the maxillary sinus, has been shown to be an important anatomical structure for the formation of sinusitis. The obstruction of osteomeatal complex causes chronic sinusitis. The opening of a closed OMC could result in improvements in the symptoms of sinusitis [22]. In recent years, functional endoscopic sinus surgery has been used successfully to open the obstruction of the ostium [23]. We think that edema and thickening of the sinus mucosa caused by an infection related to MRONJ may obstruct the OMC. We performed an antrectomy in order to prevent a recurrence. We have not seen any recurrence in our patients. Nevertheless, Maurer et al. [5] reported that recurrences of sinusitis maxillaries in three of eight antrectomy cases. But in these cases, the defect was closed with a local mucosal flap.

BFP has been successfully used to close oroantral fistulas, to reconstruct the defects occurred after trauma or excision of pathological masses. It has also been reported that this technique could be employed in mandibular deficiencies [9, 10]. Because of the fat tissue is highly vascularized, it provides an adequate blood supply to the MRONJ site. This is considered a positive contribution, which could be a good treatment option in osteonecrosis cases.

Growth factors lead to mitosis of cells by inducing stem cells in the wound area and promote angiogenesis and osteogenesis [24]. These growth factors have shown that after activation from the platelets moving into the fibrin matrix, they stimulate a mitogenic response of the periosteum cells to provide bone healing [25]. Furthermore, cytokines are released from the platelets and are responsible for regulating platelet activation. Cytokines also have important roles such as proliferation and differentiation of leukocytes, immunology and functioning of the mechanisms of inflammation [24]. Hence, the PRF increases tissue vascularization, catalyzes the healing of epithelial wounds and improves soft tissue regeneration. Because of these reasons, we believe that in our cases we experienced better recovery and recoverable dehiscence in the postoperative period because we applied both PRF and BFP.

Limitations of this study include the difficulty in stabilizing PRF in very large bone defects. In addition, this study included only a limited number of patients, as it included only cases of MRONJ with maxillary sinusitis. Therefore, the efficacy of PRF and BFP can be investigated in larger patient series involving the same patient group.

Conclusion

In this study, oroantral fistulas that caused by MRONJ were successfully managed with a combined treatment consisted of an antibiotic regimen, sequestrectomy, PRF and BFP. We suggest that bone defects arose from MRONJ can be managed with such a combined approach in order to lessen the recurrence risk.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Agbaloo T, Mebrotra B, O’Ryan F. American Association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72(10):1938–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, Moulopoulos LA, Melakopoulos I, Bozas G, Koutsoukou V, Gika D, Anagnostopoulos A, Papadimitriou C, Terpos E, Dimopoulos M. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8580–8587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, Engroff SL. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(5):527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mast G, Otto S, Mucke T, Schreyer C, Bissinger O, Kolk A, Wolff KD, Ehrenfeld M, Stürzenbaum SR, Pautke C. Incidence of maxillary sinusitis and oro-antral fistulae in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40(7):568–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurer P, Sandulescu T, Kriwalsky MS, Rashad A, Hollstein S, Stricker I, Hölzle F, Kunkel M. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the maxilla and sinusitis maxillaris. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40(3):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolanmaz D, Tuz H, Bayraktar S, Metin M, Erdem E, Baykul T. Use of pedicled buccal fat pad in the closure of oroantral communication: analysis of 75 cases. Quintessence. 2004;35(3):241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egyedi P. Utilization of the buccal fat pad for closure of oro-antral and/or oro-nasal communications. J Maxillofac Surg. 1977;5(4):241–244. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0503(77)80117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poeschl PW, Baumann A, Russmueller G, Poeschl E, Klug C, Ewers R. Closure of oroantral communications with Bichat’s buccal fat pad. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(7):1460–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallego L, Junquera L, Pelaz A, Hernando J, Megias J. The use of pedicled buccal fat pad combined with sequestrectomy in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the maxilla. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17(2):e236–e241. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotaru H, Kim MK, Kim SG, Park YW. Pedicled buccal fat pad flap as a reliable surgical strategy for the treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(3):437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy S, Driggs J, Elgharably H, Biswas S, Findley M, Khanna S, Gnyawali U, Bergdall VK, Sen CK. Platelet-rich fibrin matrix improves wound angiogenesis via inducing endothelial cell proliferation. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19:753–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJJ, Mouhyi J, Gogly B. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second generation platelet concentrate part II: platelet related biologic features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e45–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He L, Lin Y, Hu X, Zhang Y, Wu H. A comparative study of platelet rich fibrin (PRF) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on the effect of proliferation and differentiation of rat osteoblasts in vitro. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gülşen U, Şentürk MF, Mehdiyev I. Flap-free treatment of an oroantral communication with platelet-rich fibrin. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54:702–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, Gogyl B. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(9):1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Goodger NM, Pogrel MA. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with cancer chemotherapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(9):1104–1107. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Migliorati CA. Bisphosphanates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(22):4253–4254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen MR, Burr DB. The pathogenesis of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: so many hypotheses, so few data. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(5 suppl):61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otto S, Hafner S, Mast G, Tischer T, Volkmer E, Schieker M, Stürzenbaum SR, Tresckow EV, Kolk A, Ehrenfeld M, Pautke C. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: is pH the missing part in the pathogenesis puzzle? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(5):1158–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato M, Grasser W, Endo N, Akins R, Simmons H, Thompson DD, Golub E, Rodan GA. Bisphosphonate action. Alendronate localization in rat bone and effects on osteoclast ultrastructure. J Clin Invest. 1991;88(6):2095–2105. doi: 10.1172/JCI115539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell GW, Joshi BB, Macleod RI. Maxillary sinus disease: diagnosis and treatment. Br Dent J. 2011;210(3):113–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa F, Emanuelli E, Robiony M, Zerman N, Polini F, Politi M. Endoscopic surgical treatment of chronic maxillary sinusitis of dental origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(2):223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta V, Bains BK, Singh GP, Mathur A, Bains R. Regenerative potential of platelet rich fibrin in dentistry: literature review. Asian J Oral Health Allied Sci. 2011;1:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gassling V, Douglas T, Warnke PH, Açil Y, Wiltfang J, Becker ST. Platelet-rich fibrin membranes as scaffolds for periosteal tissue engineering. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:543–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]