Abstract

Introduction

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders can be treated by both conservative and surgical approaches. Conservative interventions with predictable benefits can be considered as first-line treatment for such disorders. Dextrose prolotherapy is one of the most promising approaches in the management of TMDs, especially in refractory cases where other conservative management has failed.

Aim

To study the efficacy of prolotherapy and to establish it as an effective procedure in patients with TMJ disorders, to provide long-term solution to chronic TMJ pain and dysfunctions.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a study on 25 patients suffering from various TMJ disorders who were treated with prolotherapy, the solution consisting of 1 part of 50% dextrose (0.75 ml); 2 parts of lidocaine (1.5 ml); and 1 part of warm saline (0.75 ml). The standard programme is to repeat the injections three times, at 2-week interval, which totals four injection appointments over 6 weeks with 3-month follow-up.

Results

There was appreciable reduction in tenderness in TMJ and masticatory muscles with significant improvement in mouth opening. The effect of the treatment in improving clicking and deviation of TMJ was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05). There were no permanent complications.

Conclusion

Our study concluded that prolotherapy is an effective therapeutic modality that reduces TMJ pain, improves joint stability and range of motion in a majority of patients. It can be a first-line treatment option as it is safe, economical and an easy procedure associated with minimal morbidity.

Keywords: Prolotherapy, TMJ, TMD, Dextrose, Refractory

Introduction

According to Task force on Taxonomy of the International Association for the study of pain (IASP), pain has been defined as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage”. The pain can be mainly classified as acute and chronic. Merskey describes chronic pain as persistent pain that is not amenable as a rule, and range of treatments starts from specific remedies to the symptomatic relief from pain by taking non-narcotic analgesics [1]. One of the most common causes of non-odontogenic chronic facial pain is temporomandibular disorders (TMD), an umbrella term, that describes various conditions causing pain and dysfunction of TMJ. Commonly associated symptoms with TMDs include pain at the joint, orofacial pain, chronic headaches and ear aches, including hyper- and hypo-mobility, locking of the jaw, dysfunction of the jaw, clenching or talking difficulty, clicking sounds while opening and closing of the mouth, but occasionally it also presents without any pain [2].

Since surgery is considered as the last resort for TMD, it is common for patients to look for other alternatives and prolotherapy is one of the alternative treatment options, also known as regenerative injection therapy (RIT).

Prolotherapy, as defined by Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, is “the rehabilitation of an incompetent structure, such as a ligament or tendon, by inducing the proliferation of cells”. The word “Proles” means growth. Prolotherapy injections cause stimulation or proliferation of growth of new, normal ligament and tendon tissues [3, 4].

It is a natural, minimally invasive, simple technique that stimulates the body to repair the painful area by assisting natural healing process. Dextrose injection is deposited into the ligament in order to produce a proliferative response of that ligament. The purpose of these injections is to strengthen the ligaments and relieve pain.

It is a promising approach in the management of TMDs, especially in refractory cases where conservative management has failed [5].

The present study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of prolotherapy in TMJ disorders.

Patients and Methods

We studied 25 patients who presented with temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD) to the emergency and outpatient Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, between January 2016 and September 2017. The study protocol for the present study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB). A prior written informed consent was taken from all the participants in the study.

The diagnosis of TMJ disorders was based on previous history and clinical examination. The criteria for inclusion in this study were mainly pain or tenderness in the temporomandibular joints under load during function, pain in and around ear, difficulty in chewing, difficulty in mouth opening, occasional locking of the joint, chronic dislocation with objective evidence of a injury or disorder to tendon or ligament, refractory cases in which conservative management (physical, medical, dietary, home care) therapy has failed and patients in whom surgical management is contraindicated. The exclusion criteria were allergy to the components of prolotherapy solution (Dextrose) or an active state of infection, healing disorder, parafunctional habits (Bruxism), etc.

We used 3 ml of 12.5% dextrose solution as prolotherapy agent, consisting of 1 part of 50% dextrose (0.75 ml); 2 parts of 2% lidocaine (1.5 ml) and 1 part of warm saline (0.75 ml).

The needle insertion points were marked on the skin according to the method suggested by Hemwall-Hackett (Fig. 1). The first target is to locate the posterior joint space. Target area is the depth of the depression that forms immediately anterior to the tragus (approximately 5 mm from middle margin of tragus, over ala tragal line) as the condyle translates forwards and downwards after opening the mouth. After placing a bite block, the injection needle penetrates the skin at the marked point and is directed towards antero-medially to avoid penetration into the ear and 1 ml of prolotherapy solution is deposited.

Fig. 1.

Marked injection sites for dextrose prolotherapy

The second target area is the anterior disc attachment, where superior portion of the lateral pterygoid muscle inserts into the disc. Palpation of this target area is done by taking reference of the posterior joint space and head of condyle. During closing the mouth when the condyle glides back into the fossa, mark the slight depression point just anterior to it. While insertion, direction of the needle is towards medially and angulated slightly anteriorly to its full one-inch length. Another 1 ml of prolotherapy solution is deposited after aspiration.

Most of the patients had some muscular tension and pain with resultant strain on its attachment to the zygomatic arch. The third target is to palpate and address the most rigid, tender area of masseter muscles by asking the patient to clench the teeth. The patient is told to relax the jaw, and final 1 ml of the solution is deposited into this area.

The standard protocol is to repeat the injections three times at an interval of 2 weeks. The patients were asked to visit for follow-up, 1 month and 3 months after last dose of prolotherapy.

At each appointment, we examined tenderness of affected muscles and palpated both joints for pain and clicking. We also measure the range of jaw motion intrinsically and record all these findings. The results were documented under the following findings—(a) tenderness of joint and masticatory muscles (Fig. 2) (b) level of pain, (c) mouth opening and (d) assessment of presence or absence of clicking (Fig. 3) and deviation while opening the mouth (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of tenderness in TMJ at different time intervals

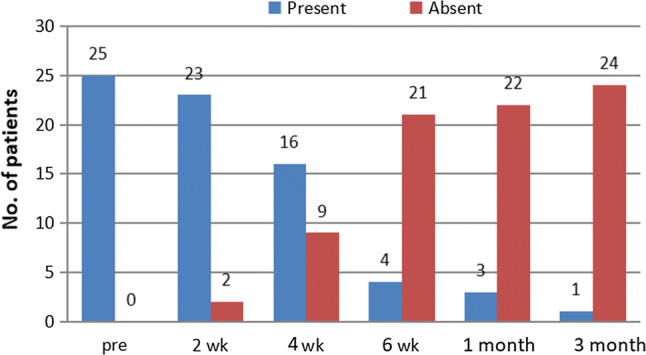

Fig. 3.

Frequency of clicking in TMJ at different time intervals

Fig. 4.

Frequency of deviation in TMJ at different time intervals

The data were analysed to evaluate the efficacy of prolotherapy in TMJ disorders. All the statistical method was carried out through the SPSS for windows (version 22). These descriptive statistics were employed in the present study—mean, standard deviation, frequency and per cent. ‘Crammers v’ formula was used to find significant differences in frequencies between time intervals. Repeated measures ANOVA used to check changes in VAS score, mouth opening at different time intervals. Probabilities of less than or equal to 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant.

Results

In our study, out of the 25 patients, 18 patients (72%) were female and 7 (28%) male with age ranged between 18 and 70 years with a mean age of 38 years. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the patients.

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution

| Age | Sex | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| < 25 | |||

| Frequency | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Per cent | 28.6 | 22.2 | 24.0 |

| 26–50 | |||

| Frequency | 2 | 9 | 11 |

| Per cent | 28.6 | 50.0 | 44.0 |

| 50+ | |||

| Frequency | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Per cent | 42.9 | 27.8 | 32.0 |

| Total | |||

| Frequency | 7 | 18 | 25 |

| Per cent | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Clinical findings were noted down on a proforma for all the patients. Relevant clinical parameters were assessed pre-operatively and during subsequent appointments, i.e. at 2nd week, 4th week, 6th week visit and post-operatively after 1 month and 3 months. The data collected were subjected to statistical analysis comprising of descriptive statistics.

Intensity of pain was evaluated using VAS (visual analogue scale). We observed that the mean pre-operative pain was 7.04 and after first dose of prolotherapy (2 weeks after) mean pain was 5.28, after second dose of prolotherapy (4 weeks after) mean pain was 4.28, and after third dose of prolotherapy (6 weeks after) mean pain was 3.64. After 1 month post-operatively mean pain was 3.40, after 3 months’ post-operatively mean pain was 3.16. Average decrease in pain level was 3.88, which indicates that there is a substantial reduction in pain after the therapy. There was statistically significant difference in decrease in mean pain level from pre- to post-therapy periods at the end of 3 months (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Mean pain value (VAS) at different time intervals

The mean maximum mouth opening pre-operatively was 22.88 mm. After first dose of prolotherapy (after 2 weeks) it was 25.84 mm, after second dose of prolotherapy (after 4 weeks) it was 29.68 mm, after third dose of prolotherapy (after 6 weeks) it was 31.12 mm, and after 1 month post-operatively (after fourth dose of prolotherapy) it increased to 31.92 mm. These subjects were reviewed after 3 months of prolotherapy, and the mouth opening had substantially increased to 32.88 mm by the end of the therapy. The mean increase in mouth opening was found to be 10 mm. There was a statistically significant difference in the increase in mouth opening from pre-operative to post-operative period at the end of 3 months (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Mean mouth opening (mm) at different time intervals

The effect of the treatment for clicking (Fig. 3) and deviation (Fig. 4) was decided on the basis of the proportion of improvement at the end of the treatment by noting their presence or absence. Significant (P < 0.05) association was observed from pre-operative to post-operative follow-up (3 months after last dose of prolotherapy).

All patients accepted the prolotherapy injection well with no serious complications. There were considerably low number of incidents of dizziness and facial palsy. Out of 25 patients, three patients felt mild dizziness which is most likely because of anxiety about the procedure and they recovered within an hour. Ten patients reported transient facial palsy which diminished within 2 h post-operatively. Mild extra oral preauricular swelling was noted in four patients which disappeared within an hour.

Discussion

There is a widespread use of various injection therapies for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions by medical practitioners. The material most commonly injected is often a combination of a corticosteroid and an anaesthetic into joints and peritendinous areas. However, there are several other techniques and agents that are currently being used, including prolotherapy, platelet-rich plasma, autologous whole blood, dry needling and acupuncture [6, 7].

Various pathologies involving the TMDs including joint subluxations, disc displacements, as well as muscle spasms and myofascial pain patterns cause weakening of the TMJ capsule and ligament. TMJ sounds such as clicking, popping, or crepitation, pain, restricted jaw movement and irregular jaw movement are obvious symptoms of TMDs.

While the exact cause of chronic temporomandibular dysfunction is still debated, our study demonstrated that the Hemwall-Hackett technique of dextrose prolotherapy not only reduces the pain level for those having chronic TMDs, but also improves overall quality of life. Dextrose prolotherapy involves injections in and around the joint, in the fibro-osseous junction of the ligament and capsular attachments on the zygomatic arch and condyle of mandibular. Clearly, the fundamental goal of this therapy is to improve the stability of the TMJ by improving capsular and ligament strength [2, 8, 9]

In our study, the main ingredient in the active solution was dextrose, the most common proliferant used in prolotherapy compared to others. It is easily available, economic with high safety profile. Though more than 10% dextrose concentration partially works by inflammation, it may utilize both inflammatory and non-inflammatory mechanisms.

In a prospective study, Refai et al. evaluated the efficacy of dextrose prolotherapy for the treatment of TMJ hypermobility. They demonstrated that 10% dextrose prolotherapy seemed promising for the treatment of symptomatic TMJ hypermobility [10, 11].

The most common cause of TMJ pain is myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome which primarily involves the muscles of mastication. Conventional treatment modalities such as intraoral orthosis, physiotherapy, pain medications, home exercises and dietary restrictions offer temporary relief; they rarely cure the condition. Underlying laxity is mostly responsible for persistent muscle spasm which will cause myofascial pain and TMJ dysfunction. Prolotherapy acts by stimulating ligament and capsular repair thus providing a more permanent and long-lasting relief.

Prolotherapy reinitiates the inflammatory response, enhances the natural healing process of the body by stimulating fibroblast proliferation which consequently results in strengthening the joints, tendons and ligaments, and thus reduces pain.

The improvement of mouth opening was assessed by recording the maximum interincisal distance. The mouth opening of these subjects improved successively by the last dose of the therapy. There was statistically significant difference in increase in mouth opening from pre-operative to post-operative period at the end of 3 months.

The improvement in mouth opening could be a result of reduction in pain or reduction in surface friction or viscosity of synovial fluid. It was satisfactory to assess the patients post-operatively as there was a drastic improvement noted.

Post-operative review of these patients treated with prolotherapy demonstrated significant therapeutic benefits and showed a significant reduction in symptoms after prolotherapy. Statistics confirmed a significant difference in post-treatment outcome in pain and tenderness in joint, masticatory muscles and also in interincisal mouth opening with reduction in clicking and deviation. The results of this study therefore suggest that Hackett-Hemwall dextrose prolotherapy has many indisputable advantages and can play a significant role in decreasing pain, improving mobility and range of motion. It also reduces the use of medications, thus improving the quality of life in the patients with unresolved temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs).

Prolotherapy can be considered as a great alternative prior to long-term narcotic therapy or surgical intervention. It represents a more permanent solution by repairing joint ligaments and capsules, thus relieving persistent and refractory problems associated with the TMJ [10–12].

In our study, prolotherapy was done mainly in refractory patients, who had been previously treated with various alternatives like intraoral soft splints, physical therapy, dietary restrictions and home care. Final result of our study revealed that prolotherapy can be very effective treatment even in patient with long-standing history of TMJ pain. However, we speculate that the success of prolotherapy would be all the better when used in milder cases of TMDs, but we do not yet have the statistics to support this hypothesis. Continued research on the effectiveness of prolotherapy in patient populations with varying histories, set of symptoms and levels of TMD severity is needed.

Conclusion

Our study concluded that prolotherapy is a simple and minimally invasive procedure, with little or no risk of complications; it has also revealed promising benefits in terms of significant pain reduction levels, stiffness, crunching sensation, disability, depression, anxiety, clicking and deviation. They also reported with improved interincisal mouth opening. The study is compatible with the findings of similar work done worldwide.

In our descriptive study, dextrose prolotherapy used on patients presented with TMJ pain and dysfunction showed an improved quality of life. The result supports that it can be considered as an alternative treatment for people suffering with unresolved temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction.

However, the success of prolotherapy and the requirement for additional therapy necessitates a judicious approach with patience.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Saubhik Dasukil, Email: souvikdasukil@gmail.com.

Sujeeth Kumar Shetty, Email: shettymaxfax@gmail.com.

Geetanjali Arora, Email: geetanjaliarora28@gmail.com.

Saikrishna Degala, Email: degalasaikrishna@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. Task force on taxonomy. International Association for the Study of Pain. 2. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. pp. 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein RG, Eek BC, DeLong WB, Mooney V. A randomized double blind trial of dextrose-glycerine-phenol injections for chronic, low back pain. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:23–33. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeelani S, Krishna S, Reddy J, Reddy V. Prolotherapy in temporomandibular disorders: an overview. Open J Dent Oral Med. 2013;1:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Distel LM, Best TM. Prolotherapy: a clinical review of its role in treating chronic musculoskeletal pain. PM&R. 2011;3(6 Suppl 1):S78–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauser RA, Hauser MA, Blakemore BA. Dextrose prolotherapy and pain of chronic TMJ dysfunction. Pract Pain Manag. 2007;7:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milaro M, Ghali GE, Larsen PE, Waite PD. Petersons principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vankdoth S, Reddy S, Adamala, Talla H. Prolotherapy—a venturing treatment for temporomandibular joint disorder. IJSS Case Rep Rev. 2014;1(7):27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakala RV, Ledermann KM. The use of prolotherapy for temporomandibular joint dysfunction. J Prolother. 2010;2:435–446. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauser RA, et al. A systemic review of dextrose prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;9:139–159. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S39160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majumdar SK, et al. Single injection technique prolotherapy for hypermobility disorders of TMJ using 25% dextrose: a clinical study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2016;16(2):226–230. doi: 10.1007/s12663-016-0944-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Refai H. Long-term therapeutic effects of dextrose prolotherapy in patients with hypermobility of the temporomandibular joint: a single-arm study with 1–4 years’ follow up. BJOMS. 2017;55:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou H, Ding Y, Hu K. Modified dextrose prolotherapy for the treatment of recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52(1):63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]