Abstract

Existing research adopting a sex positive and intersectional framework for investigating Black women’s sexualities is scarce. We conducted a 46-year (1972–2018) content analysis of sexualities research focused on Black women. It sought to examine which sexualities topics were published most; whether the publications aligned with sex-positive, neutral or negative discourse; what methodologies were used; and differences in how various identities were investigated among Black women. Using human coding, we applied an integrative approach to this content analysis. Results found 245 articles meeting criteria. Approximately one-third of articles within the analysis focused on the topic of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV and sexual risk behaviours among Black women. Only 6.5% of articles utilised a sex-positive discourse. Quantitative articles were the most published methodology, and publications disproportionately overlooked Black women’s intersectional identities. Implications for future research and practice are discussed.

Keywords: Black women, sexuality, content analysis, sex positivity, intimate justice

Introduction

Black women are estimated to represent 52.2 percent of the Black adult population in the USA (U.S. Census Bureau 2018). These nearly 21.5 million Black women embody diverse ethnic, socioeconomic, religious/spiritual and sexual identities, among other aspects of sociocultural within-group differences (Bowleg 2008; Crenshaw 1991). Yet, sex research using samples of Black women often narrowly represents their multifaceted sexual lives. Many studies, informed by public health and medical model perspectives, approach the study of Black women’s sexualities from a risk-based stance (Buzi et al. 2018; Raiford, Seth and Diclemente 2013; Wade et al. 2014). Consequently, there are major gaps in the literature representing Black women’s sex lives comprehensively.

The current study sought to systematically review the way Black women in the USA have been sampled, studied and represented in sex research. In this content analysis, we answer several questions related to discourse on Black women’s sexuality in the literature. Specifically, we examined which sexualities topics were published most; whether existing publications aligned with sex-positive, neutral, or negative discourse; what research methodologies were used; and differences in how intersectional identities were captured among Black women. Expanding the codebook first used by Hargons, Mosley and Stevens-Watkins (2017), we represent the current status of sexology on Black women. We then provide implications and recommendations for the next era of enquiry on Black women’s sexualities.

History of Black Women’s Sexualities

The history of Black women’s sexualities is extensive yet understudied, resulting in an incomplete understanding of Black women’s attitudes and beliefs related to sex, sexual practices and sexual pleasure (Hammonds 2004). History continues to shape conversations and the examination of Black women’s sexualities through controlling racialised gendered stereotypes and messaging rooted in chattel slavery in the USA (Lewis 2005; Lewis et al. 2016; Stephens and Phillips 2003; West 1995). Evidence suggests the widespread use of racialised gendered stereotypes such as the Jezebel, Mammy or Sapphire can lead to either an overemphasis on sexuality or repressed sexual desires and unfulfilled needs, and may impact Black women’s sexual attitudes, beliefs and behaviours (Thomas, Witherspoon and Speight 2004). For example, the antithesis of the desexualised Mammy is the promiscuous and sexually available Jezebel. The Jezebel is arguably the most pervasive stereotype and conserves an oversexed view of Black women’s sexuality (Brown, White-Johnson and Griffin-Fennell 2013). These three historical racialised gendered stereotypes of Black women continue to undergird Black women’s sexualities in a dichotomy of asexual and hypersexual, limiting the ability to view their sexuality in a more positive and holistic manner (Thomas, Crook and Cobia 2009; Ware, Thorpe and Tanner 2019). These stereotypic representations obscure variations in Black women as sexual beings who are not wholly defined by their sexuality and can develop healthy sexual identities.

Black Women’s Sexualities in Research

Recent (Cunningham 2019; Miller-Young 2014; Nash 2014) and classic (Lorde 1984) publications have explored Black women’s sexuality in a manner that critiques dominant sex-negative discourses. Instead, these authors offer radical, healthy, holistic, liberatory and otherwise sex-positive frameworks for considering Black women’s sexualities. Interdisciplinary scholars offer both theoretical (e.g. the “erotic” in Sister Outsider, Lorde 1984; “brown sugar” in A Taste for Brown Sugar: Black Women in Pornography, Miller-Young 2014) and real life (e.g. “Blax-porn-tation,” Nash 2014; and rapper Nicki Minaj, Cunningham 2019) examples of how Black women reappropriate sex-negative discourses and strive toward “the freedoms that ecstasy can bring” (Nash 2014, 151).

However, in the sexual sciences, Black women are typically the subject of sex-negative discourse (Lewis 2005), particularly regarding sexual behaviours that contribute to sexual health disparities (Benard 2016). For example, Black girls and women are targeted for prevention and intervention efforts related to sexual promiscuity and the reduction of sexual infection transmission such as HIV (Jones 2019). It is important to understand how this creates an unbalanced view of Black sexuality.

Intersectionality in sexualities research

Previous research fails to capture where intersectional identity and sexuality converge for Black women. Instead, enquiry is predominantly focused on White women’s sexual development (Crooks, King and Tluczek 2019). Sparse accounts of cultural variation is concerning given the influence of social inequality and intracultural differences on sexual behaviours and wellbeing (Higgins and Hirsch 2007). Intersectionality posits interdependent axes of power including racism, sexism and classism shaping lived experience, meaning-making and life outcomes (Cole 2009). Particularly for Black women, multiple forms of oppression converge (Crenshaw 1991). Intersectionality theory may be used to address how social location informs Black women’s sexualities. Additionally, intersectionality broadens the scope of sexuality research to encourage a more holistic and positive view of sexuality (Jones 2019).

Sexual scripts and behaviour, age of sexual consent and marriage, access to sexual education, and what is categorised as sexual dysfunction can vary based on predominant messages and norms informed by discriminatory systems of power (Brown, Blackmon and Shiflett 2018; Heinemann, Atallah and Rosenbaum 2016). Additionally, some Black women experience interlocking systems of oppression. For example, Black LBTQ women hold a “triple whammy” of intersecting marginalised identities (Bowleg et al. 2003) and tend to be discriminated against not only on racial grounds but also because of their sexuality and sexual behaviour. When researchers fail to consider and capture how interlocking systems of privilege and oppression inform their research (Cole 2009), nuanced differences of Black women’s sexualities are ignored. There is a need to appreciate the complexity of Black women’s social identities and sexualities (and their intersections) to avoid monolithic representations of this group (Jenkins Hall and Tanner 2016).

Intimate Justice and Critical Sexualities

In many ways, intersectionality and sex positivity influence each other. A combined understanding of intersectionality and sex positivity is offered by McClelland’s (2010) notion of intimate justice. Intimate justice considers how social and political forces affect personal experiences to inform what individuals want, need and believe they deserve related to sexual pleasure and satisfaction (McClelland 2010). Black women and their bodies continue to endure systemic and epistemic constraint, coercion and violence that hinders their experiences of sexual pleasure (Threadcraft 2016). An intimate justice framework suggests the need to provide corrective racial justice for Black women by exploring their most intimate desires (Threadcraft 2016). Such a framework seeks to integrate intersectionality with sex positivity. It supports revolutionary reclamation of exploited, constrained, abused and multiply marginalised sexual selves, which sexual science should apply to the study of Black women. In research, the application of this framework involves a focus on sexual pleasure to promote wellbeing despite societal constraints (McClelland 2010).

Mowatt, French and Malebranche (2013) argue that Black women’s voices and experiences are frequently silenced, deeming them invisible in research and beyond. Paradoxically, however, Black women are also made hyper visible through media representation, pornography and sex work (Jones 2019; Jerald et al. 2017; Mowatt, French and Malebranche 2013). Although Black women have made significant contributions to sexology, gynaecology, reproductive justice and other fields as researchers and participants, the knowledge, skills and experiences of these women continue to be underreported (Flowers 2018). Further, many Black women lack access to research findings, which perpetuates inequity for Black girls and women seeking to learn about sexuality and sexual pleasure (Flowers 2018). Regardless of depictions related to Black women’s hypersexuality, research often suggests they are void of sexual pleasure and satisfaction, which may reflect limited expectations of sexual satisfaction (Holland et al. 1992), a narrow empirical representation absent of Black women’s sexual pleasure, or both.

Methodology

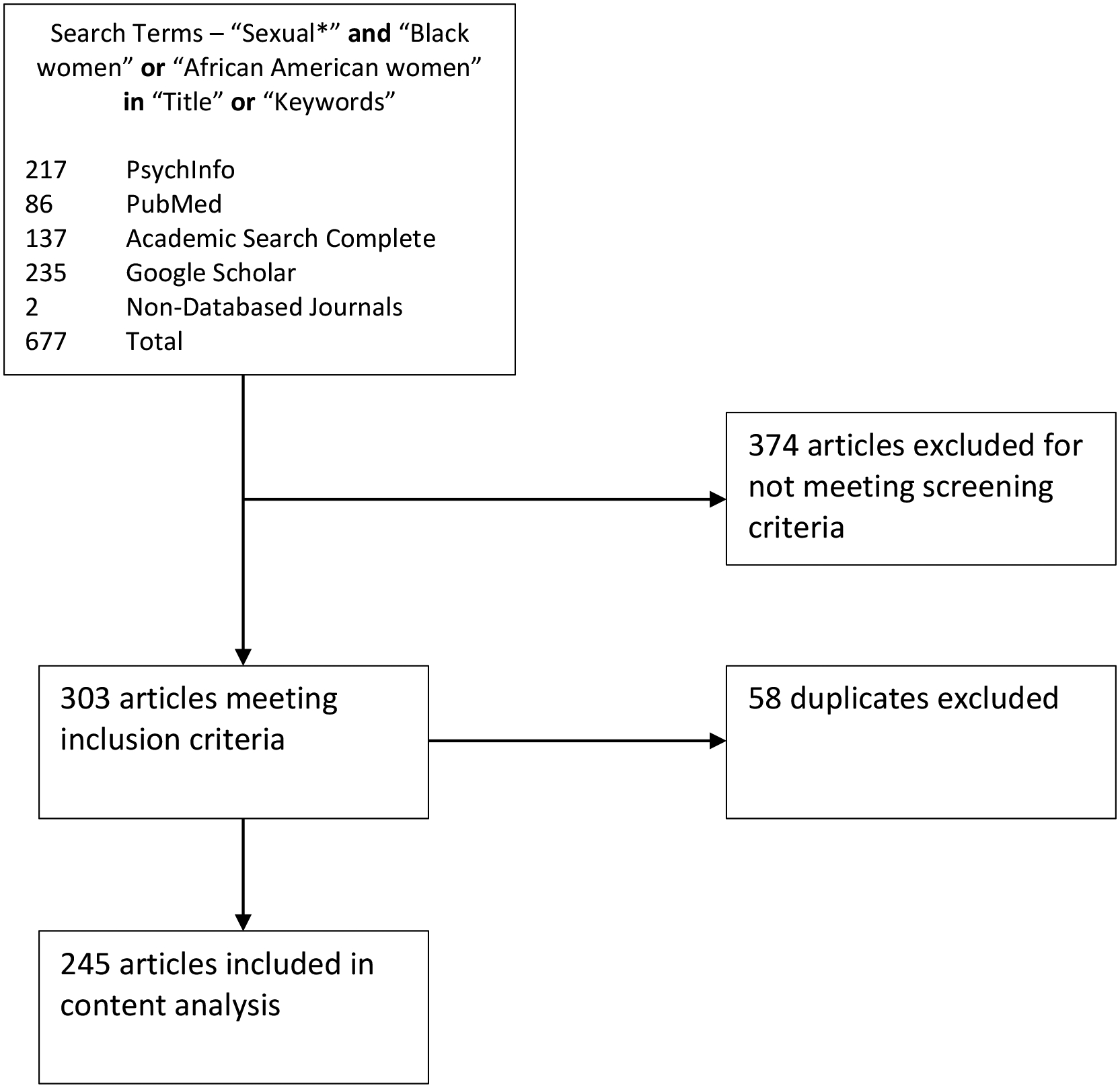

This study took the form of a content analysis examining the research literature published between 1972 to 2018 on the topic of Black women’s sexuality and sexual health. Of special interest were the discourses, methodologies and participant demographics present in the literature. In support of the study, the second author conducted an initial search of the literature using the following databases: PsychInfo, PubMed, Academic Search Complete, Google Scholar, and the Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships in 2018. Due to limited access to international journals, only research published in the USA was included in this analysis. Six hundred seventy-seven articles were found during the initial search. The first three co-authors then excluded articles that focused on anatomical sex rather than sexuality as reflected in identities, behaviours and lifestyles. This left a total of 374 articles for review. In February 2019, the research team conducted a second literature review using the same databases. Search terms for both searches included sexual*, Black women, and African American women in the title or as keywords, which resulted in 303 articles.

Upon review, a total of 58 articles were excluded because they were duplicates of previously identified articles, leaving a total of 245 articles for more detailed analysis. Articles were then organised by relevance and date of publication (See Figure 1). The first three co-authors coded articles based upon the following categories: methods (e.g. quantitative, qualitative, conceptual); discourse (sex positive, neutral, sex negative); research topic; and participant demographics (ethnicity, sample characteristics - All Black women, most, or comparisons, sexual diversity, religious/spiritual affiliation, socioeconomic status).

Figure 1.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for Content Analysis

Hargons, Mosley and Stevens-Watkins’ (2017) earlier work on sexuality served as a template for the content analysis, which was also informed by recommendations made by Neuendorf (2011). We focused on message content (Black women’s sexualities) and coded article discourses as sex positive (pleasure focused), neutral, or sex negative (deficit-focused) (Arakawa et al. 2013; Hargons et al. 2018; Lewis 2004). Where differences in coding were identified, the team consulted with the second author to determine the code. The final categorisation of topic codes is listed in the Appendix.

After organising articles by discourse and topic, we coded their methodology as quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods or conceptual. Literature reviews and commentaries were included in the conceptual category, in line with Reimers and Stabb’s (2015) suggestions. All the articles were then reviewed to determine their demographic composition. Because we wanted to distinguish between participants who might identify as African American, African, Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latinx, articles were coded as “yes” or “no” if they included an ethnic breakdown of their samples. Articles with samples of all Black women were coded as All Black (AB). Where more than half, but not all, of the sample was Black, articles received a MOST code. When Black women were compared to women of other races such as White and Latina, articles received a COMP code. Conceptual articles received a Not Applicable (NA) code given they did not include study participants. Lastly, we reported if articles included information about sexual diversity (yes/no), religious background (yes/no), and socioeconomic background (None, All Low, Predominately Low, Predominantly Middle/Upper).

Findings

Black Women’s Identities

The first research question was “How are the ethnic, sexual, religious/spiritual, and socioeconomic identities of Black women reported in sexualities research?”

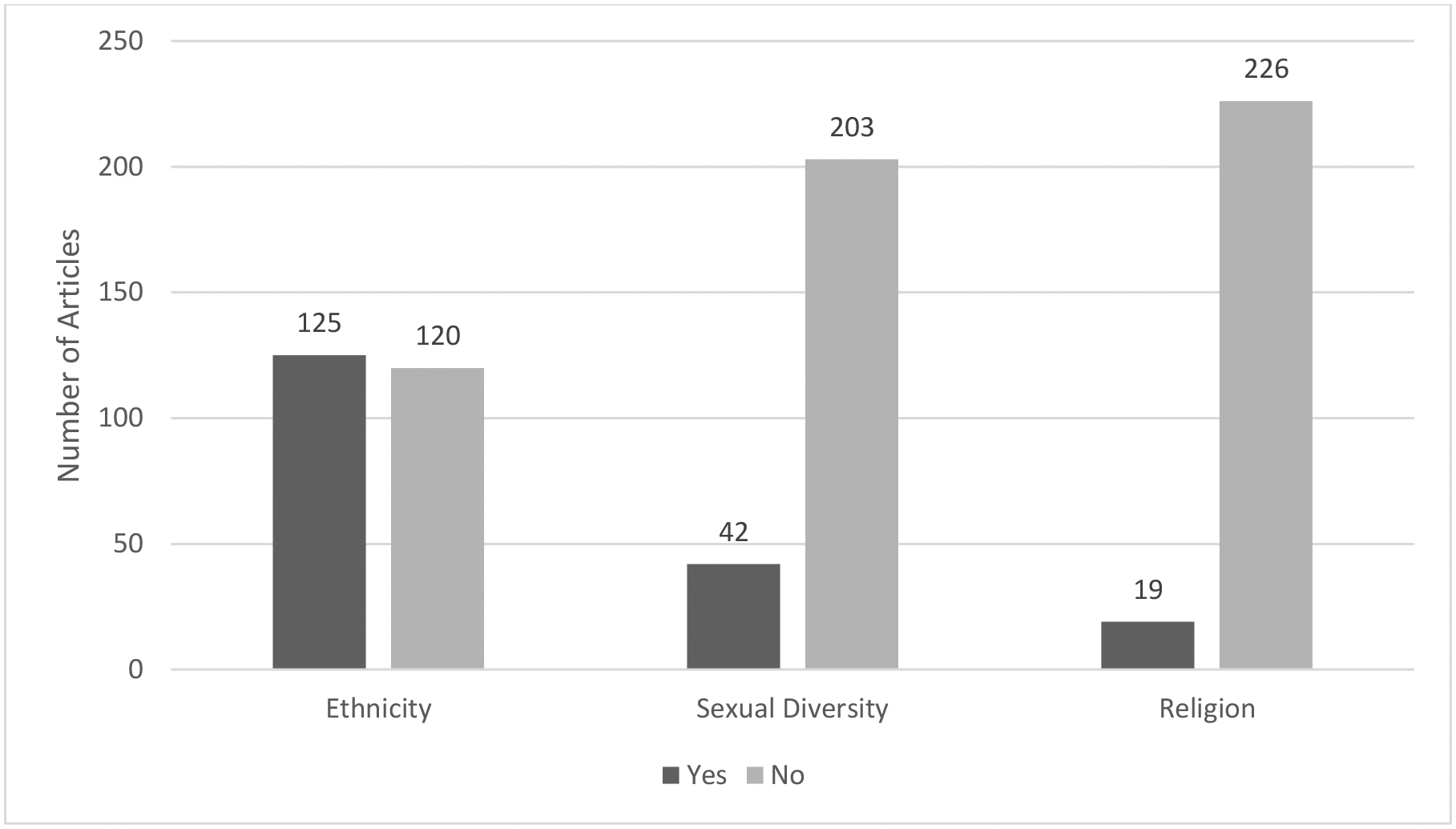

Of the two hundred and forty-five articles, most of the research did not include information on the intersecting identities of participants with respect to sexual diversity, religion and socioeconomic background. An approximately equal number of papers reported on the ethnicity of Black women as did not (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Representation of Ethnic, Sexual and Religious Identity of Black Women in Sexuality Research

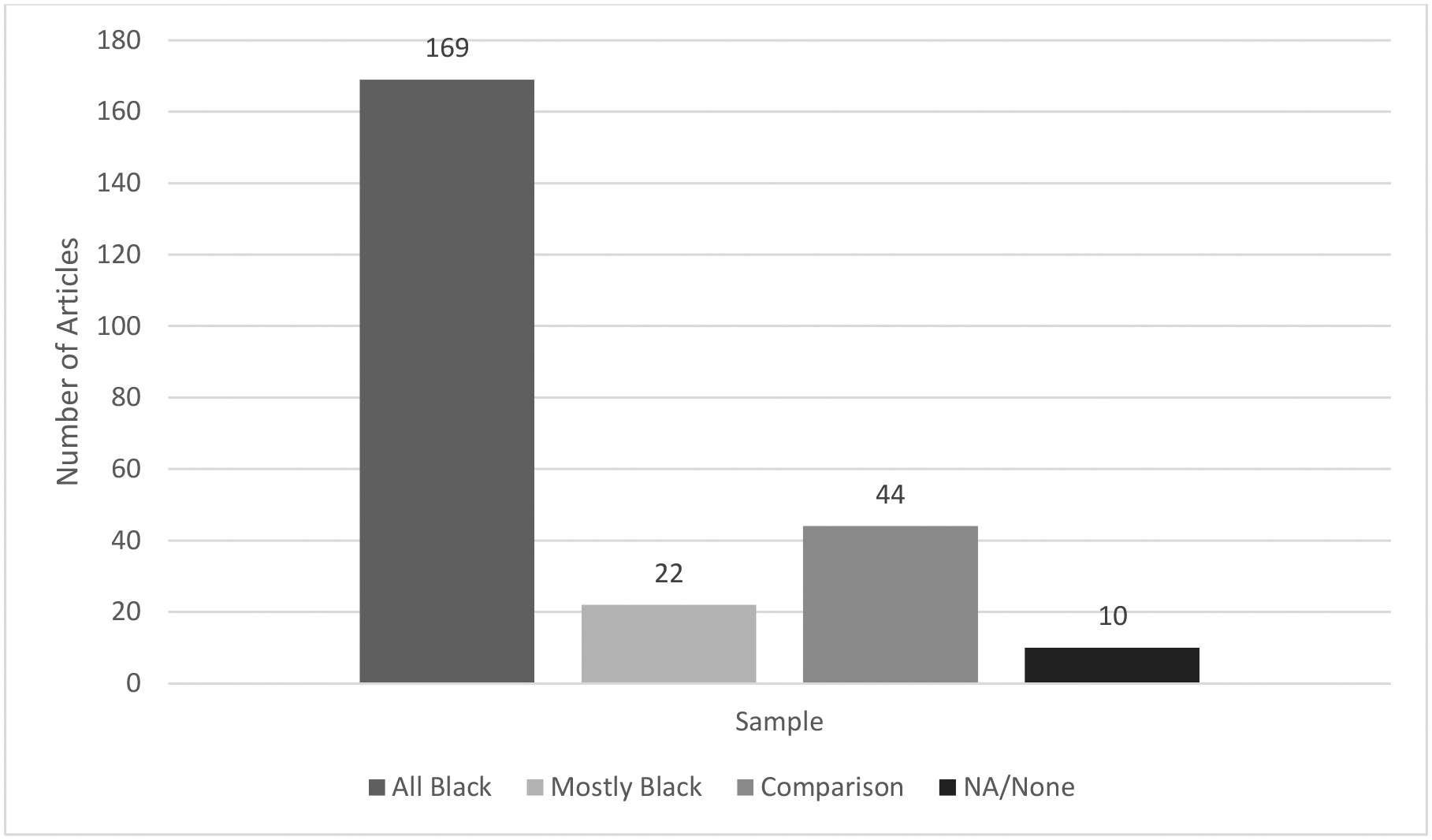

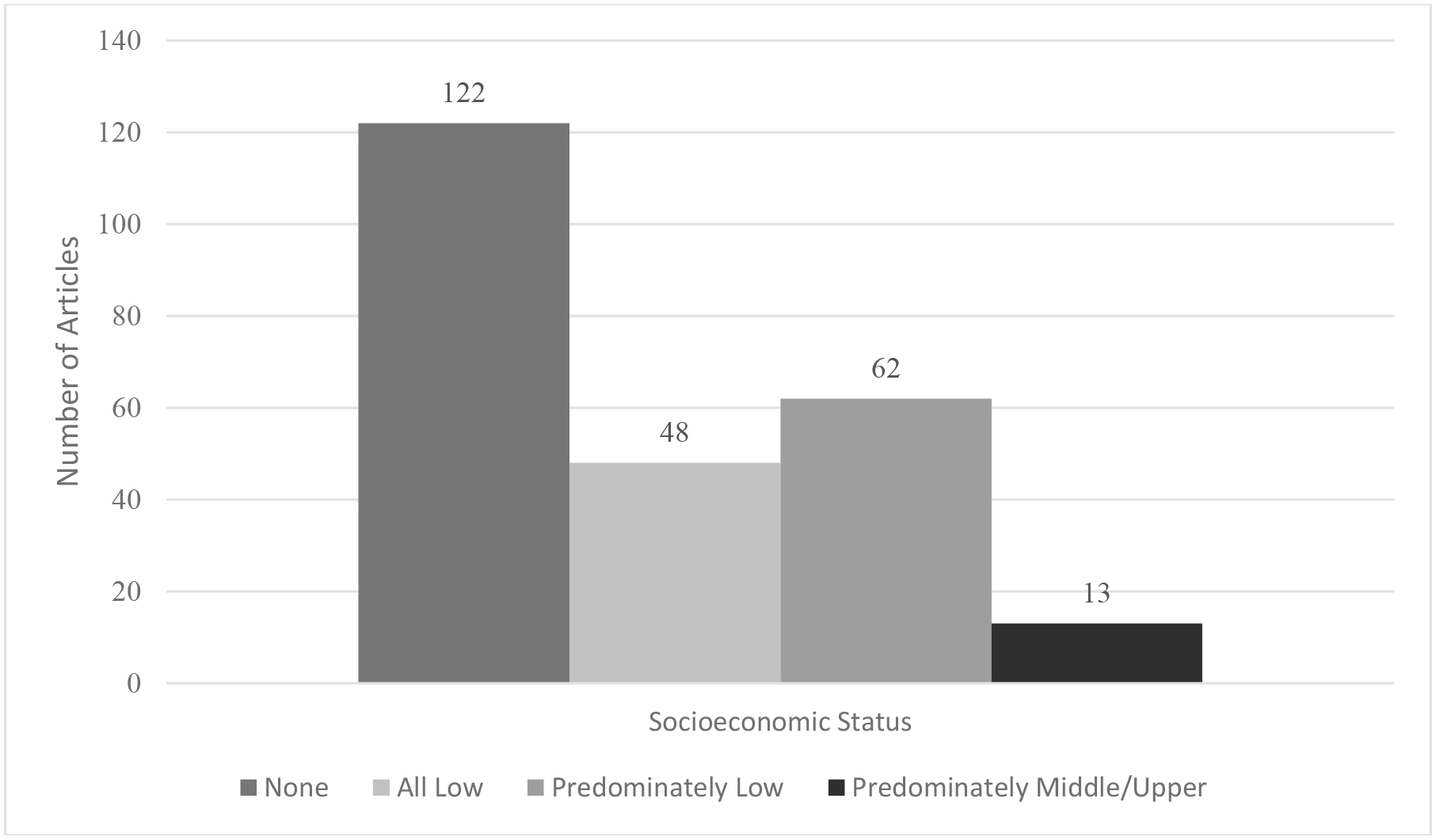

Additionally, most of the articles included an all-Black sample (see Figure 3). Last, the majority of articles did not report the socioeconomic status of the Black women in their samples. However, when socioeconomic background (e.g. in terms of annual income, education level and/or employment status) was captured, more of the samples comprised low-income Black women compared to middle- or upper-SES Black women (see Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Composition of Samples of Black Women in Sexuality Research

Figure 4.

Socioeconomic Status of Black Women in Sexuality Research

The second research question was as follows: “What percentage of studies represent Black women’s identities narrowly versus comprehensively?” We defined narrowly as meaning that one or two aspects of identity were focused on in a study as opposed to the comprehensive coverage of three or more identities. Given the focus on intersectionality within our content analysis, nearly all (n= 221; 99%) studies narrowly represent the converging identities of Black women in sexualities research by focusing on two or fewer aspects of identity.

Topics focused upon

To better understand how Black women’s sexualities were examined in existing literature, the third research question was, “What topics have been published in Black women’s sexualities research?” We identified seven main topic areas, with the majority focusing on STIs, HIV and sexual risk (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency and Percentage of Black Women’s Sexuality Topics Published

| Topics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual orientation and identity | 21 | 6.15 |

| Sexual abuse, objectification, and victimisation | 74 | 21.7 |

| Sexually transmitted infections, HIV, and sexual risk | 123 | 36.0 |

| Sexual counselling, education, and therapy | 5 | 1.46 |

| Sexual functioning, satisfaction, and pleasure | 17 | 4.98 |

| Sexual health communication, attitudes, and values | 26 | 7.62 |

| Sexual development, socialisation, and behaviours | 75 | 21.9 |

Note. N = 341 because some articles related to more than one category.

Methodologies used

The fourth research question was “What methods have been used to facilitate this research?” A total of 147 (60%) of the studies included in our analysis utilised quantitative methods, while 59 (24%) used qualitative methods and 5 (2%) were mixed-methods studies. There were 34 conceptual articles, which included literature reviews, commentaries and descriptions of sexual health interventions that focused on Black women. Of the 34 conceptual articles, 10 articles made reference to study samples, but did not focus in on participants’ social identities.

Sexualities Discourse

The fifth and last research question was “Do the studies embody a sex positive, neutral, or negative perspective?” Most (n= 203; 83%) articles adopted a sex-negative perspective, focusing on issues such as STIs, HIV and sexual risk behaviours; sexual development and socialisation; and sexual abuse, objectification and victimisation. Neutral articles, on topics about sex counselling, education and therapy or sexual health communication, attitudes, and values, comprised a mere 10.6% of the sample (n = 26). Articles containing sex-positive discourses on Black women were few in number (n=16, 6.5%) and reported mostly on sexual function, satisfaction and pleasure.

Discussion

Despite a recent surge in research exploring tenets of Black sexualities, facilitated by the founding of the Association of Black Sexologists and Clinicians, and its accompanying journal and conferences, there is a need for more sex-positive research that attends to Black women’s intersecting identities. For example, the first sex positive empirical article focused on Black women was published in 2003 (Shulman and Horne 2003), nearly thirty years into our 46-year content analysis about Black women’s sexualities. Furthermore, June Dobbs Butts (1977), a foremother in sex positive Black research, called for a more comprehensive examination of Black sexualities over four decades ago.

This content analysis revealed that sexualities research is not immune to the focus on deficit discourses that plagues the social sciences more broadly, particularly in the study of People of Colour and Indigenous peoples (Fogarty et al. 2018; Tuck and Yang 2012). To promote the healthy sexual development and well-being of Black women, a strengths-based, intimate justice perspective would be beneficial (McClelland 2010). Incorporating positive aspects into discourse concerning Black women’s sexualities draws attention to eudaemonic sexual health, which emphasises elements of sex-positivity (e.g. sexual satisfaction, pleasure, consent). Taken together, our findings suggest Black women’s sexualities are largely portrayed through a sex negative lens in the literature reviewed for this study. Furthermore, existing research is often void of an intersectional framework that would allow a more nuanced understanding of Black women’s experiences. In her essay regarding sexuality and African traditions, Ifi Amadiume (2006) argues for the need for critical discourse on responsible sexuality without projecting guilt, fear and warnings of negative health consequences. The published research reviewed in this content analysis misses the opportunity to do this.

Many (60%) of the studies examined used quantitative methodology. Quantitative research often focuses on sexual behaviours, STIs and HIV, pregnancy, contraceptive use and age of sexual debut all of which are used to inform and support a sex-negative narrative (Lamb, Roberts and Plocha 2016). Findings signal the extent to which epistemologies that are valued in White, Western cultures are utilised on Black women, raising questions about their appropriateness for advancing knowledge about Black women’s sexuality and sexual health. More research is needed that goes beyond examination of Black women in dire need of protection from STIs and pregnancy. Additionally, sex-positive qualitative or mixed-methods research with an intersectional framework may provide a more in-depth account of Black women’s experiences. In a society where Black women are denied access to wellness in myriad ways (e.g. living wages, Kim 2009; wealth, Brown 2012; interpersonal safety, Norwood 2018; good quality health care, Moaddab et al. 2018), understanding what sexual pleasure might mean to Black women is a radical intervention sexual scientists can make.

To develop a counternarrative of sex-positive research, there needs to be more research focusing on sexual pleasure and satisfaction, as well as sexual counselling and education among Black women (Jones 2019). These areas are gravely underinvestigated. Despite pleasure being accepted as a key part of sexual health by the World Health Organization (2006), studies have continued to primarily focus on sexual pleasure among White samples, although scholars argue that sexual pleasure has been understudied broadly (Higgins and Hirsch 2007). This is problematic because it maintains historical legacies in which Black sexualities are linked to labour-and-loss and White sexualities to pleasure-and-profit (Miller-Young 2014). Furthermore, since “representations shape the world in which Black women come to know themselves” (Miller-Young 2014, 5), the lack of focus on pleasure among Black women is psychologically, physically and spiritually oppressive. Developing new research with a focus on sexual pleasure and satisfaction is key to having a more comprehensive understanding of Black women’s sexuality (Ware, Thorpe and Tanner 2019) and advancing discourse on Black sexology (Hargons, Mosley and Stevens-Watkins 2017).

Most of the samples in the publications reviewed were either all Black or majority Black. Researchers should continue to utilise a non-comparative approach to further examine within-group differences of Black women with other marginalised intersecting identities, because comparing Black women with White women in sexualities research amplifies the sex-negative narrative, considers Black women as a race-gendered monolith with limited within-group differences, and limits empirical perspectives of the diversity of their sexuality. Our findings also demonstrated that very few studies took a comprehensive approach to investigate Black women’s sociodemographic factors such as socioeconomic status (SES), sexual identity, religion and ethnicity. Research focused on Black women’s sexualiys disproportionately relies on samples of Black women from lower-SES backgrounds, who are often viewed as at highest risk for sexual health disparities due to economic constraints, access barriers to care, and limited comprehensive sexualities education (Sales et al. 2014). However, Black middle- and upper- income women should also be the focus of sex research, because Black women of different socioeconomic status may not experience their sexuality in the same way (Townsend 2008). In particular, very few studies have explored queer Black women’s sexuality, regardless of discourse. This stands in stark contrast to the extent to which queer Black men have been sampled and studied, so an opportunity to holistically examine the sexualities of queer Black women, especially the positive, protective components, is a necessary direction for future research.

Religiosity, another factor that shapes Black women’s sexuality, was minimally reported in the literature. Religious adherence has been linked to sexual shame and guilt among Black women (Harris-Perry 2011). Some religious messages teach that the expression of any form of sexuality is deviant and focus on abstinence until marriage, which ignores the right to varied sexual beliefs, desires, behaviours and pleasures (Murray, Ciarrocchi and Murray-Swank 2007). Religiosity also provides the underpinning for respectability politics, which establishes how Black women should act and which behaviours are deserving of dignity and respect (Collins 2004; Lamb, Roberts and Plocha 2016). Feelings of shame and guilt from religiosity and respectability politics may deter Black women from exploring the desires that shape their sexual experiences, pleasure and satisfaction, therefore future research should examine how religiosity and spirituality impact Black women’s sexualities.

It is also important to examine ethnic differences among Black women (Morgan, Mwegelo and Turner 2002). Although half of the studies reported ethnicity, the ethnicities were often African American or African. Race, a socially defined concept, and ethnicity, linked to a distinctive ancestry and cultural customs, are often and erroneously used interchangeably (Cokley 2007). Ethnocultural factors may influence African American women’s sexualities differently from Black women from African, Caribbean, and Latin-American countries. The interplay of multiple systems of oppression and privilege shapes Black women’s worldviews and sexual experiences (Collins 1998, 2004; Crenshaw 1991). Such a perspective aligns with an intimate justice framework (McClelland 2010; Threadcraft 2016). Therefore, it is critical for sexuality researchers to explore these experiences and promote the sexual wellness of Black women holding the above and other identities from an intersectional and sex-positive framework.

Finally, more research on sex therapy and sex positive sex education specific to Black women is needed to gain insight into their needs, experiences, perceived barriers, and sexual health outcomes resulting from those interventions (e.g. improvements in their overall sexual well-being and other dimensions of health). Despite the existence of many sex therapists and educators of colour (e.g. those identifiable through Afrosexology; the Association of Black Sexologists; The Minority Sex Report; and the Women of Color Sexual Health Network), publications relevant to Black women’s sex counselling, education and therapy represented less than 2% of the studies identified.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study paper that warrant discussion. First, although there was potential for human error during the coding process, efforts were made to avoid this by team-based coding with multiple checks. Second, the research covered in the analysis was conducted only in the USA. Future research would benefit from partnership with scholars in universities in other parts of the African diaspora to identify a larger pool of articles to analyse. Third, the search terms used in the content analysis (e.g. sexual*, Black women and African American women) were limited to the title and keyword database fields. The use of additional fields such as medical subject headings (MeSH), and a focus on additional aspects of sexuality and gender identities (e.g. womxn, AFAB) might have broadened the scope of our analysis.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to explore how Black women’s sexuality is represented in existing sex and sexuality research literature. Overall, Black women are narrowly presented with a negative discourse regarding sex, sexuality and sexual behaviour. A greater emphasis on sex positivity and intersectionality will lead to a better understanding of how worldviews, culture and identity influence the sexuality and sexual behaviours of Black women. Sexualities are culturally mediated; therefore, this paper calls for more attention to culture and ideology in sex research, with greater thoughtfulness regarding the research questions, methodologies and purpose of research with populations who members may hold multiple marginalised identities. For Black women specifically, their shared background but unique experiences deserve a more thorough, holistic and just investigation in future research.

Acknowledgments

The second author is a US National Institute on Drug Abuse T32 trainee at the University of Kentucky under NIDA Grant T32DA035200 (PI: Rush). The funding agency had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, or the preparation and submission of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Institutes of Health.

Appendix. Content Analysis Codebook

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| STI – Sexually transmitted infections and sexual risk | These articles include research on HIV, AIDS, and other STIs, as well as pregnancy prevention. Sexual behaviours identified as influencing the risk to contract STIs or unwanted pregnancy, such as condom use, are included. |

| SO – Sexual orientation, identity, and minorities | These articles include research on people who identify as LGBTQIA, as well as heterosexual identity development and issues associated with conversion counselling or attempts to change sexual orientation. |

| SA – Sexual abuse, objectification, or victimisation | These articles include research on survivors of sexual abuse, incest, and sexual assault. Also included are articles on sexual objectification, aggression, rape, and molestation, perceived or perpetuated. |

| SF – Sexual functioning, satisfaction, and pleasure | These articles include research on sexual functioning, including sexual dysfunction disorders found in the DSM-5, sexual satisfaction, and sexual pleasure. Reproduction-related topics are also included. |

| SH – Sexual health communication, attitudes, and values | These articles include research on sexual communication among partners and attitudes and values people hold or share about sexuality. |

| SC – Sexual counselling, education, and therapy | These articles include research on sex counselling and therapeutic interventions for sexual issues, as well as sex education prevention interventions and outreach. |

| SD – Sexual development, socialisation, and behaviours | These articles include research on the influences (developmental changes, familial and social (e.g. music) messages, and drug use) on sexual scripts and behaviour. |

| E – Sex-Positive discourse | These articles include topics related to sexual pleasure, satisfaction, improving sexual functioning, and advocating for the sexual rights of LGBTQIA and other marginalised groups. They align with the elements of a sex-positive framework. |

| P – Sex-Negative discourse | These articles include topics that relate to prevention of sexual health risks, such as contracting an STI, treating an STI, preventing sexual victimisation, and preventing unwanted pregnancy. |

| N – Neutral discourse | These articles relate to describing or evaluating sexual health interventions without a positive or negative valence. |

| Qual – Qualitative Research | These articles include studies that employ qualitative methodologies, such as consensual qualitative research, grounded theory, and case studies. |

| Quant – Quantitative Research | These articles include studies that employ quantitative methodologies, such as quasi-experimental design, cross-sectional survey research, and scale development. |

| Mixed – Mixed Methods Research | These articles include studies that employ a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. |

| Conc – Conceptual Research | These articles include literature reviews, commentary, and introductions to special issues. |

| Narrow Identity Representation Comprehensive Identity Representation | Articles that explored one or two social identities (e.g. race, SES, gender, sexual orientation, religion) of study participants Articles that explore three or more identities (e.g. race, SES, gender, sexual orientation, religion) of study participants. |

| AB – All Black Women | These articles have samples that comprise only Black women. |

| Most – Mostly Black Women | These articles have samples that comprise more than 50% Black women. |

| Comp – Comparison with Other races | These articles compare samples of Black women to samples of women from other races/ethnicities. |

| N/A – Not Applicable | These articles do not have a sample because they are conceptual or theoretical. |

Note. Black = individuals of African descent to include African American, African, Caribbean and Latinx identified women; LGBTQIA = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual; DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

References

- Amadiume Ifi. 2006. “Sexuality, African Religio-cultural Traditions and Modernity: Expanding The Lens.” Codesria Bulletin 1 (2): 26–28. http://www.arsrc.org/downloads/features/amadiume.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa DR, Flanders CE, Hatfield E, and Heck R. 2013. “Positive Psychology: What Impact Has It Had on Sex Research Publication Trends?” Sexuality and Culture 17 (2): 305–20. 10.1007/s12119-012-9152-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benard AF 2016. “Colonizing Black Female Bodies Within Patriarchal Capitalism.” Sexualization, Media, & Society 2 (4): 1 11. 10.1177/2374623816680622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair CM 2014. “African American Women’s Sexuality.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 35 (1): 4–10. 10.5250/fronjwomestud.35.1.0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L 2008. “When Black + Lesbian + Woman ≠ Black Lesbian Woman: The Methodological Challenges of Qualitative and Quantitative Intersectionality Research.” Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 10: 87–108. 10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L 2012. “The Problem with the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—An Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health.” American Journal of Public Health 102 (7): 1267–1273. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Huang J, Brooks K, Black A, and Burkholder G. 2003. “Triple Jeopardy and Beyond: Multiple Minority Stress and Resilience Among Black Lesbians.” Journal of Lesbian Studies 7 (4): 87–108. 10.1300/J155v07n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T 2012. “The Intersection and Accumulation of Racial and Gender Inequality: Black Women’s Wealth Trajectories.” The Review of Black Political Economy 39 (2): 239–258. 10.1007/s12114-011-9100-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL, White-Johnson RL, and Griffin-Fennell FD. 2013. “Breaking the Chains: Examining the Endorsement of Modern Jezebel Images and Racial-Ethnic Esteem among African American Women.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 15 (5): 525–539. 10.1080/13691058.2013.772240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL, Blackmon S, and Shiflett A. 2018. “Safer Sexual Practices among African American Women: Intersectional Socialisation and Sexual Assertiveness.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (6): 673–689. 10.1080/13691058.2017.1370132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne J and Russell S. 2005. “My Home, Your Workplace: People with Physical Disability Negotiate their Sexual Health without Crossing Professional Boundaries.” Disability & Society 20 (4): 375–388. 10.1080/09687590500086468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butts JD 1977. “Inextricable Aspects of Sex and Race.” Contributions in Black Studies 1 (5): 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Buzi RS, Weinman ML, Smith PB, Loudd G, and Madanay FL. 2018. “HIV Stigma Perceptions and Sexual Risk Behaviors among Black Young Women.” Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services 17 (1): 69–85. 10.1080/15381501.2017.1407726 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Case KA, Iuzzini J, and Hopkins M. 2012. “Systems of Privilege: Intersections, Awareness, and Applications.” Journal of Social Issues 68 (1): 1–10. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01732.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cokley K 2007. “Critical Issues in the Measurement of Ethnic and Racial Identity: A Referendum on the State of the Field.” 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER 2009. “Intersectionality and Research in Psychology.” American Psychologist 64 (3): 170–180. 10.1037/a0014564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH 1998. Contradictions of Modernity, Vol. 7. Fighting Words: Black Women and the Search for Justice. Minneapolis, MN, US: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH 2004. Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism. New York City, NY, US: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks N, King B, and Tluczek A. 2019. “Protecting Young Black Female Sexuality.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 1–16. 10.1080/13691058.2019.1632488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham A 2019. “Make it Nasty: Black Women’s Sexual Anthems and the Evolution of the Erotic Stage.” Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships 5 (1): 63–89. 10.1353/bsr.2018.0015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers SC 2018. “Enacting Our Multidimensional Power: Black Women Sex Educators Demonstrate the Value of an Intersectional Sexuality Education Framework.” Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 16 (2): 308–25. 10.2979/meridians.16.2.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty W, Lovell M, Langenberg J, and Heron MJ. 2018. “Deficit Discourse and Strengths-Based Approaches: Changing the Narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Wellbeing.” Canberra, Australia: National Centre for Indigenous Studies, Australian National University and Lowitja Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Guy-Sheftall B 1992. “Black Women’s Studies: The Interface of Women’s Studies and Black Studies.” Phylon (1960-) 49 (1/2): 33–41. 10.2307/3132615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammonds E 2004. “Black (W)Holes and the Geometry of Black Female Sexuality.” The Black Studies Reader 6 (2–3): 313–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hargons C, Mosley DV, and Stevens-Watkins D. 2017. “Studying Sex: A Content Analysis of Sexuality Research in Counseling Psychology.” The Counseling Psychologist 45 (4): 528–46. 10.1177/0011000017713756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargons CN, Mosley DV, Meiller C, Stuck J, Kirkpatrick B, Adams C, and Angyal B. 2018. “‘It Feels So Good’: Pleasure in Last Sexual Encounter Narratives of Black University Students.” Journal of Black Psychology 44 (2): 103–27. 10.1177/0095798417749400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Perry MV 2011. Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann J, Atallah S, and Rosenbaum T. 2016. “The Impact of Culture and Ethnicity on Sexuality and Sexual Function.” Current Sexual Health Reports 8: 144–50. 10.1007/s11930-016-0088-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, and Hirsch JS. 2007. “The Pleasure Deficit: Revisiting the “Sexuality Connection” in Reproductive Health.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 39 (4): 240–247. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30042982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J, Ramazanoglu C, Scott S, Sharpe S, and Thomson R. 1992. “Risk, Power and the Possibility of Pleasure: Young Women and Safer Sex.” AIDS Care 4 (3): 273–83. 10.1080/09540129208253099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins Hall W and Tanner AE. 2016. “US Black College Women’s Sexual Health in Hookup Culture: Intersections of Race and Gender.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 18 (11): 1265–1278. 10.1080/13691058.2016.1183046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerald MC, Ward LM, Moss L, Thomas K, and Fletcher KD. 2017. “Subordinates, Sex Objects, or Sapphires? Investigating Contributions of Media Use to Black Students’ Femininity Ideologies and Stereotypes About Black Women.” Journal of Black Psychology 43 (6): 608–35. 10.1177/0095798416665967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A 2019. “Sex Is Not A Problem: The Erasure of Pleasure in Sexual Science Research.” Sexualities 22 (4): 643–668. 10.1177/1363460718760210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M 2009. “Race and Gender Differences in the Earnings of Black Workers.” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 48 (3): 466–488. 10.1111/j.1468-232X.2009.00569.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb S, Roberts T, and Plocha A. 2016. Girls of Color, Sexuality, and Sex Education. Girls of Color, Sexuality, and Sex Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 10.1057/978-1-137-60155-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D 2005. “Against the Grain: Black Women and Sexuality.” Agenda 2 (63): 11–24. 10.1080/10130950.2005.9674561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Mendenhall R, Harwood SA, and Huntt MB. 2016. “‘Ain’t I a Woman?’: Perceived Gendered Racial Microaggressions Experienced by Black Women.” The Counseling Psychologist 44 (5): 758–80. 10.1177/0011000016641193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis LJ 2004. “Examining Sexual Health Discourses in a Racial/Ethnic Context.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 33 (3): 223–34. 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000026622.31380.b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorde A 1984. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland SI 2010. “Intimate Justice: A Critical Analysis of Sexual Satisfaction.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4 (9): 663–80. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00293.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Young M 2014. A Taste for Brown Sugar: Black Women in Pornography. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moaddab A, Dildy GA, Brown HL, Bateni ZH, Belfort MA, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, and Clark SL. 2018. “Health Care Disparity and Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States.” Obstetrics and Gynecology 131 (4): 707–712. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RM, Mwegelo DT, and Turner LN. 2002. “Black Women in the African Diaspora Seeking Their Cultural Heritage Through Studying Abroad.” NASPA Journal 39 (4): 333–53. 10.2202/1949-6605.1175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mowatt RA, French BH, and Malebranche DA. 2013. “Black/Female/Body Hypervisibility and Invisibility: A Black Feminist Augmentation of Feminist Leisure Research.” Journal of Leisure Research 45 (5): 644–60. 10.18666/jlr-2013-v45-i5-4367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KM, Ciarrocchi JW, and Murray-Swank NA. 2007. “Spirituality, Religiosity, Shame and Guilt as Predictors of Sexual Attitudes and Experiences.” Journal of Psychology and Theology 35 (3): 222–34. 10.1177/009164710703500305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel J 2000. “Ethnicity and Sexuality.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 107–33. 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nash JC 2014. The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf KA 2011. “Content Analysis-A Methodological Primer for Gender Research.” Sex Roles 64 (3): 276–89. 10.1007/s11199-010-9893-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norwood CR 2018. “Mapping the Intersections of Violence on Black Women’s Sexual Health Within the Jim Crow Geographies of Cincinnati Neighborhoods.” Frontiers 39 (2): 97–135. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/698454 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CA 2000. “Defining and Studying the Modern African Diaspora.” The Journal of Negro History 85 (1–2): 27–32. 10.1086/JNHv85n1-2p27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raiford JL, Seth P, and Diclemente RJ. 2013. “What Girls Won’t Do for Love: Human Immunodeficiency Virus/ Sexually Transmitted Infections Risk Among Young African-American Women Driven by a Relationship Imperative.” Journal of Adolescent Health 52 (5): 566–71. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers FA, and Stabb SD. 2015. “Class at the Intersection of Race and Gender: A 15-Year Content Analysis.” The Counseling Psychologist 43 (6): 794–821. 10.1177/0011000015586267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Perkovich B, and Mimiaga MJ 2010. “A Mixed Methods Study of the Sexual Health Needs of New England Transmen Who Have Sex with Nontransgender Men.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 24 (8): 501–513. 10.1089/apc.2010.0059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Smearman EL, Swartzendruber A, Brown JL, Brody G, and DiClemente RJ. 2014. “Socioeconomic-Related Risk and Sexually Transmitted Infection among African-American Adolescent Females.” Journal of Adolescent Health 55 (5): 698–704. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakour M, Salehi K, and Yamany N. 2018. “Reproductive Health Needs Assessment in the View of Iranian Elderly Women and Elderly Men.” Journal of Family & Reproductive Health 12 (1): 34–41. 10.26719/2018.24.7.637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman JL, and Horne SG. 2003. “The Use of Self-Pleasure: Masturbation and Body Image among African American and European American Women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 27 (3): 262–69. 10.1111/1471-6402.00106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DP, and Phillips LD. 2003. “Freaks, Gold Diggers, Divas, and Dykes: The Sociohistorical Development of Adolescent African American Women’s Sexual Scripts.” Sexuality and Culture 7 (1): 3–49. 10.1007/BF03159848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, and Speight SL. 2004. “Toward the Development of the Stereotypic Roles for Black Women Scale.” Journal of Black Psychology 30 (3): 426–42. 10.1177/0095798404266061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CM, Crook TM, and Cobia DC. 2009. “Counseling African American Women: Let’s Talk About Sex!” The Family Journal 17 (1): 69–76. 10.1177/1066480708328565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend TG 2008. “Protecting Our Daughters: Intersection of Race, Class and Gender in African American Mothers’ Socialization of Their Daughters’ Heterosexuality.” Sex Roles 59 (5–6): 429–42. 10.1007/s11199-008-9409-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Threadcraft S 2016. Intimate Justice: The Black female body and the body politic. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck E, and Yang KW. 2012. “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. 1: 1–40. https://www.ryerson.ca/content/dam/aec/pdfs/Decolonization-is-not-a-metaphor.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. 2018. American Community Survey (ACS) 1-year estimates. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/summary-file.html

- Wade I, Miles I, Le B, and Paz-Bailey G. 2014. “Correlates of HIV Infection among African American Women from 20 Cities in the United States.” AIDS & Behavior 18 (3): 266–75. 10.1007/s10461-013-0614-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware S, Thorpe S, and Tanner AE. 2019. “Sexual Health Interventions for Black Women in the United States: A Systematic Review of Literature.” International Journal of Sexual Health 31 (2): 1–20. 10.1080/19317611.2019.1613278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- West CM 1995. “Mammy, Sapphire, and Jezebel: Historical Images of Black Women and Their Implications for Psychotherapy.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 32 (3): 458–66. 10.1037/0033-3204.32.3.458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (WHO) 2006. Working Definition of Sexual Health. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/defining_sexual_health.pdf