Abstract

We describe the convergent synthesis of a 5-O-β-D-ribofuranosyl-based apramycin derivative (apralog) that displays significantly improved antibacterial activity over the parent apramycin against wild-type ESKAPE pathogens. In addition, the new apralog retains excellent antibacterial activity in the presence of the only aminoglycoside modifying enzyme (AAC(3)-IV) acting on the parent, without incurring susceptibility to the APH(3’) mechanism that disables other 5-O-β-D-ribosfuranosyl 2-deoxystreptamine type aminoglycosides by phosphorylation at the ribose 5-position. Consistent with this antibacterial activity, the new apralog has excellent 30 nM activity (IC50) for the inhibition of protein synthesis by the bacterial ribosome in a cell-free translation assay, while retaining the excellent across-the-board selectivity of the parent for inhibition of bacterial over eukaryotic ribosomes. Overall, these characteristics translate into excellent in-vivo efficacy against E. coli in a mouse thigh infection model and reduced ototoxicity vis à vis the parent in mouse cochlear explants.

Keywords: Antibiotics, Biological Activity, Drug Design, Glycosylation

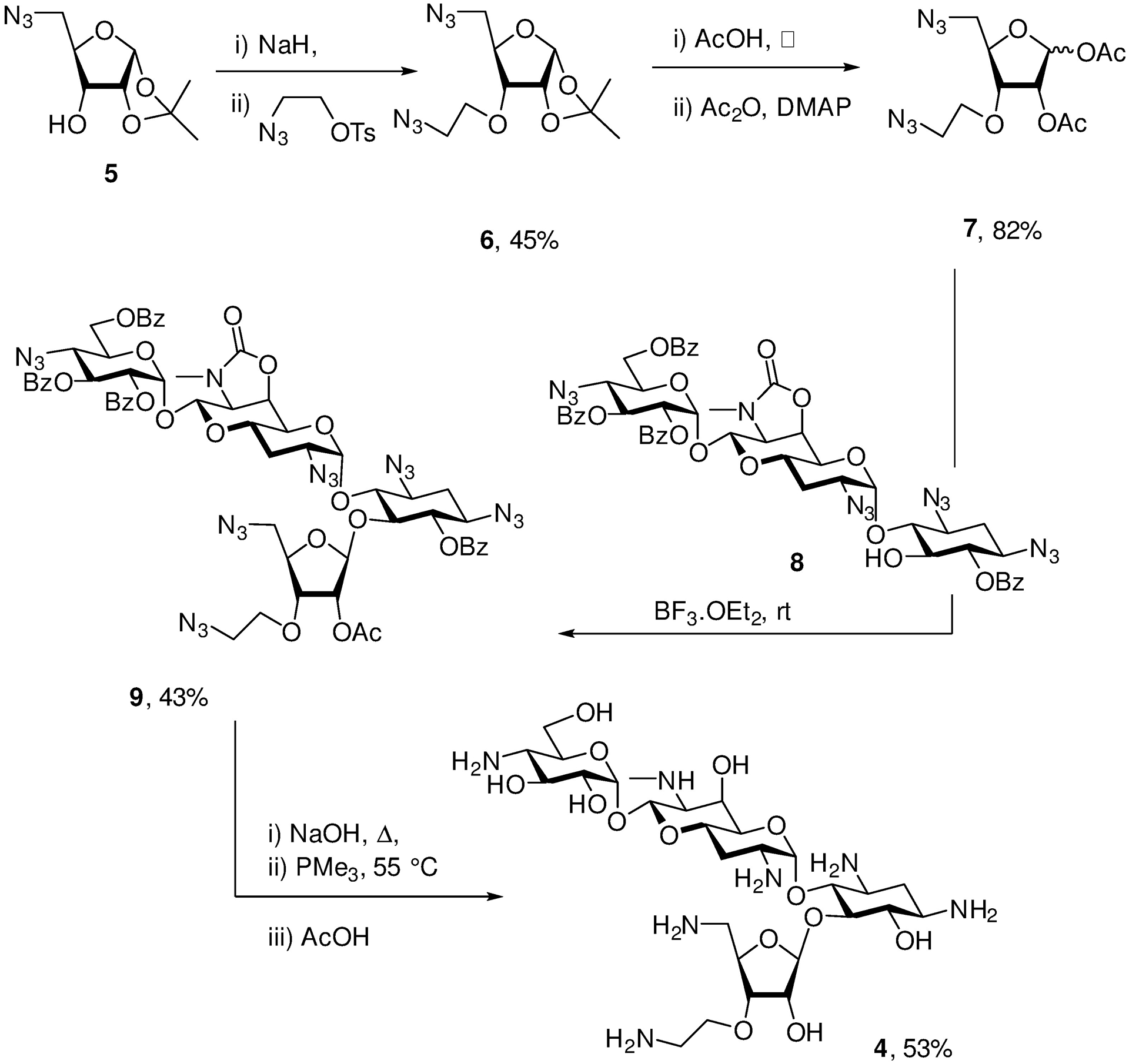

Graphical Abstract

A next generation aminoglycoside antibiotic based on the apralog concept is presented that displays excellent activity in vivo and in vitro, excellent across the board selectivity for the inhibition of bacterial over hybrid eukaryotic ribosomes, minimal ototoxicity in an ex-vivo model, and which circumvents AAC(3)-IV, the only current aminoglycoside modifying enzyme acting on the parent.

The ever-increasing spread of multidrug resistant infectious diseases demands the continued development of new and improved antibiotics. Next generation aminoglycoside antibiotics (AGAs) have much to offer in this regard in view of their ready availability, extensive and well-described chemistry and documented mechanism of action, broad spectrum activity, and lack of allergic response.[1]

Apramycin 1 is a rare example of a 2-deoxystreptamine-type (DOS) aminoglycoside that carries only a single substituent on the DOS ring in the form of a 4-aminoglucopyranosylated deoxyoctodiosyl moiety.[2] The unusual structure of apramycin prevents the action of all common aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs),[3] by far the most common cause of AGA resistance,[4] except the rare aminoacetyltrasferase isoform AAC(3)-IV.[5] The structure of apramycin also circumvents the action of the increasingly widespread G1405 16S ribosomal RNA methyltransferases,[3a, 3c, 6] whose presence nullifies all AGAs in current clinic practice including the most recently introduced plazomicin.[7] These attributes, coupled with the ready availability of apramycin and its reduced ototoxicity compared to other common AGAs,[3a, 8] have resulted in the development of apramycin as a promising therapeutic for treatment of life-threatening MDR infections, especially Acinetobacter baumannii, Enterobacterales, and other Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens,[3c] culminating in a phase I clinical trial.[9]

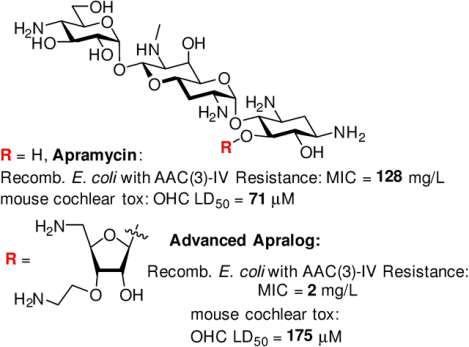

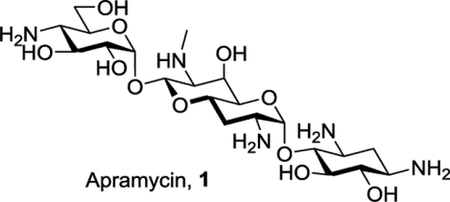

In addition to its own inherent advantages, apramycin also provides an excellent starting point for the development of next-generation AGAs that retain its multiple advantages while exhibiting enhanced levels of antibacterial activity and reduced susceptibility to the remaining resistance determinant – the AAC(3)-IV AME that acts by acetylation of N3.[3e, 5–6, 10] With this in mind, and building on the early promise of 5-O-β-D-ribofuranosyl apramycin,[11] we reported earlier on the synthesis and evaluation of a series of 5-O-furanosylated apramycin derivatives exemplified by 2 and 3 (Figure 1). As anticipated on the basis of work by the Wong group in the ribostamycin series,[12] the β-D-ribofuranosyl derivative 2 carrying a 3-O-(2-aminoethyl) substituent in the ribose ring was more active than the earlier[11] 5-O-β-D-ribofuranosyl derivative and apramycin itself with regards to both the inhibition of the bacterial ribosome (Table 1) and antibacterial activity against wild-type ESKAPE pathogens (Table 2). However, 2 showed a marked reduction in selectivity for the bacterial over the eukaryotic hydrid ribosomes carrying the human mutant mitochondrial (A1555G) decoding A site[13] (Table 1) indicative of potentially increased ototoxicity.[4g, 13] Additionally, the ribofuranosyl moiety of 2 conferred susceptibility to deactivation by the aminoglycoside phosphotransferases (APHs) acting on the ribofuranosyl primary hydroxyl group, the APH(3’,5”) isozymes.[14] Moving the pendant amino group from the ribofuranosyl 3-position of 2 to the primary ribofuranosyl 5-position, as was done in 3, restored across-the-board selectivity for the bacterial over the eukaryotic hybrid ribosomes, and eliminated deactivation by the APH(3’,5”). We now show that incorporation of aspects of both 2 and 3, namely an aminoethyl ether at the 3-position and a deoxyamino modification at 5-position of the ribose ring, into a single compound results in an improved 5-O-β-D-ribofuranosyl apramycin derivative 4.

Figure 1.

Apralogs.

Table 1.

Antiribosomal Activities and Selectivities.

| IC50 [μM] | Selectivity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | wt | Mit13 | A1555G | Cyt14 | Mit13 | A1555G | Cyt14 | |

| Apramycin | 0.15±0.05 | 119±30 | 98±33 | 129±26 | 793 | 653 | 860 | |

| 2 | 0.071±0.015 | 68±20 | 13±3 | 190±105 | 957 | 183 | 2676 | |

| 3 | 0.052±0.026 | 118±34 | 99±22 | 97±14 | 2269 | 1904 | 1865 | |

| 4 | 0.032±0.014 | 43±7 | 21±3 | 40±7 | 1343 | 656 | 1250 | |

Table 2.

Antibacterial Activities Against Wild-Type E. coli and ESKAPE Pathogens (MIC, mg/L)

| Species | E. coli | K. pneu. | Enterob. | A. baum. | P. aerug. | MRSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | AG001 | AG215 | AG290 | AG225 | AG220 | AG038 |

| Apramycin | 4 | 1–2 | 2–4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 1–2 | 1–2 | 4–8 | 16–32 | 2–4 |

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 1–2 | 4–8 | 4–8 | 4 |

| 4 | 1–2 | 0.5–1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

Results and Discussion

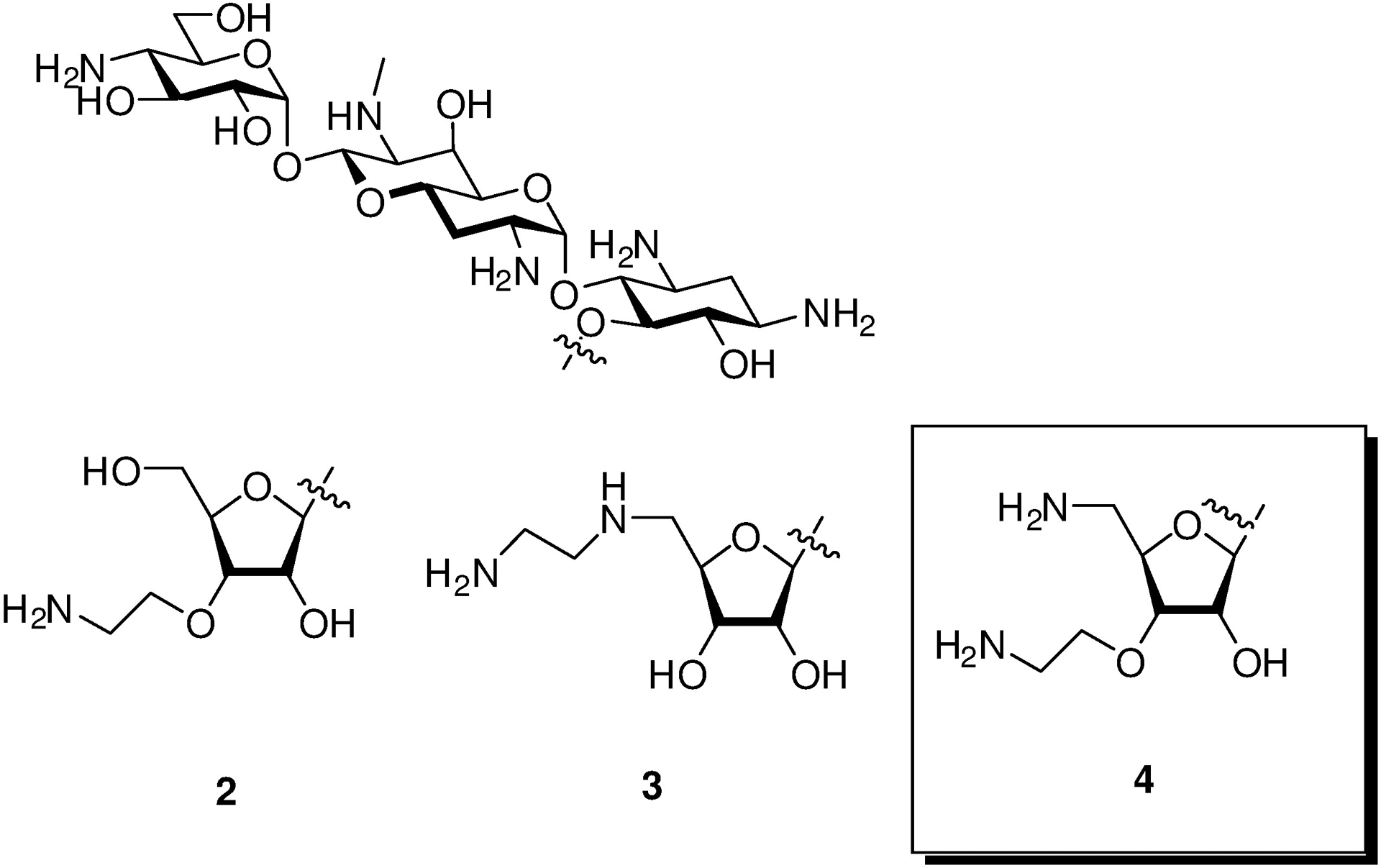

For the synthesis of 4, a donor 7 was prepared in a simple two-pot sequence via 6 from the known ribose derivative 5,[15] and coupled under robust Helferich conditions to the apramycin derivative 8 followed by a one pot deprotection sequence involving saponification and Staudinger reduction of the azido groups (Scheme 1). As 8 is available in four steps from apramycin,[10b] the synthesis of 4 requires only six steps from the parent aminoglycoside 1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis if 4.

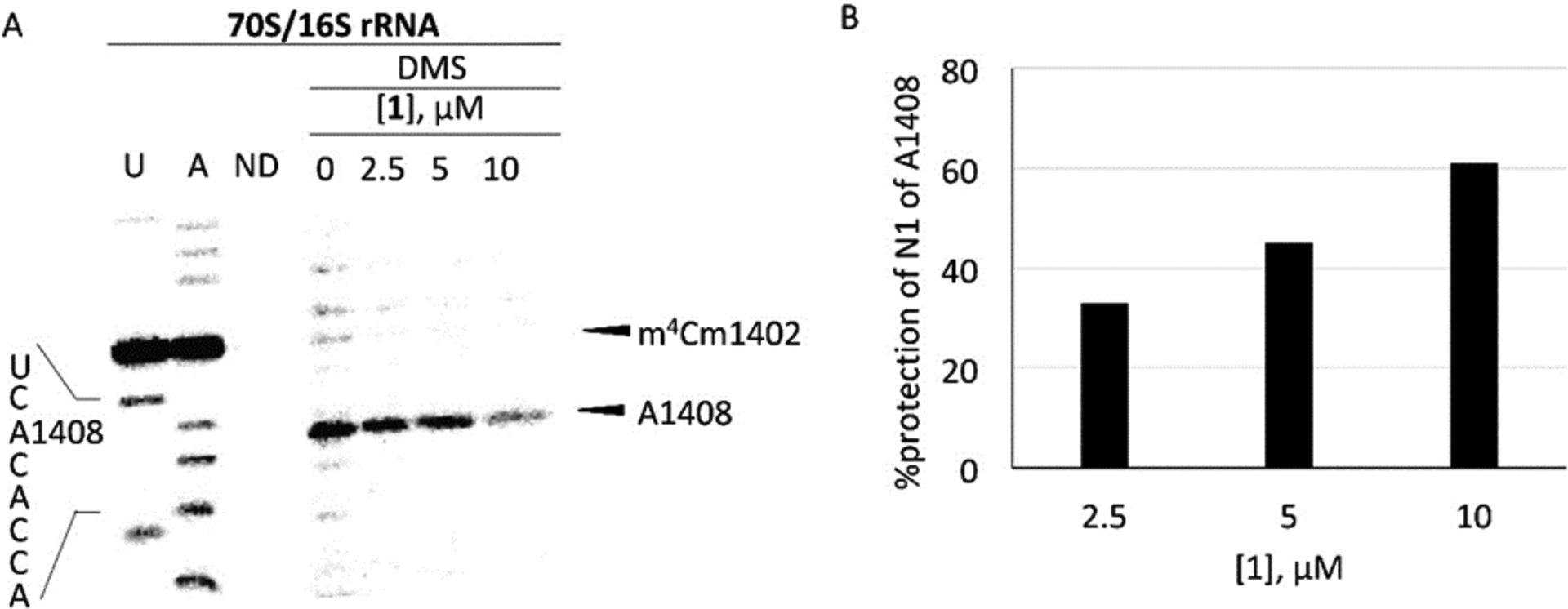

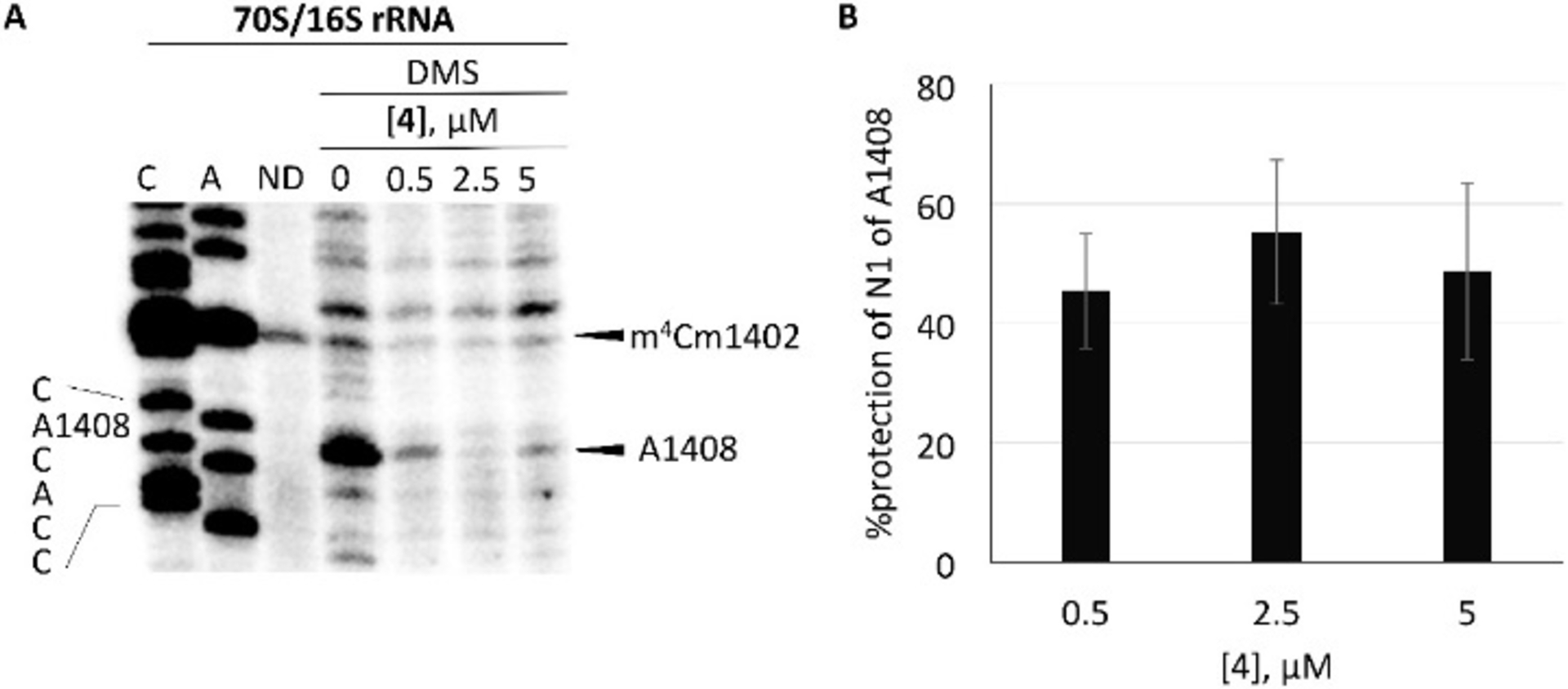

Apralog 4 was an excellent inhibitor of the bacterial ribosome for which it showed good across-the-board selectivity over the hybrid ribosomes mimicking the various eukaryotic drug binding pockets, ie, human mitochondrial (Mit13), mutant mitochondrial (A1555G), and cytoplasmic (Cyt14) decoding A sites (Table 1). We used dimethyl sulfate footprinting[16] of the E. coli 70S ribosome to demonstrate binding to A1408 in the decoding A site and estimate apparent KD values of 5 and 0.5 μM for the parent 1 and apralog 4, consistent with the relative levels of inhibition of the bacterial ribosome (Figs 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Dimethyl sulfate (DMS) footprinting of apramycin (1) binding to the A site (helix 44) region in 70S ribosomes.

(A) The autoradiogram of reacted rRNA followed by primer extension using a radiolabeled primer is shown with the A1408 sequencing stop site, DMS methylation of A1408 stop site, and naturally methylated C1402 (m4Cm1402) highlighted (U and A sequencing; ND, no DMS). Note that DMS modification produces a reverse-transcription stop site one nucleotide prior to the modified site (A1408) and dideoxy sequencing stop sites. (B) Calculated % protection of N1 of A1408 is shown with increasing concentration of 1 (single runs only).

Figure 3. Dimethyl sulfate (DMS) footprinting of 4 binding to the A site (helix 44) region in 70S ribosomes.

(A) The autoradiogram of reacted rRNA followed by primer extension using a radiolabeled primer is shown with the A1408 sequencing stop site, DMS methylation of A1408 stop site, and naturally methylated C1402 (m4Cm1402) highlighted (C and A sequencing; ND, no DMS). Note that DMS modification produces a reverse-transcription stop site one nucleotide prior to the modified site (A1408) and dideoxy sequencing stop sites. (B) Calculated % protection of N1 of A1408 is shown with increasing concentration of 4 (standard error is for three independent experiments).

In addition to this high level of inhibition of the bacterial ribosome, 4 showed outstanding activity against wild-type isolates of ESKAPE pathogens (Table 2). Turning to the inhibition of E. coli strains characterized by the presence of AAC(3) and APH(3’,5”) AMEs, we studied recombinant E. coli strains, which expressed the resistance determinants in an isogenic background. This revealed that of the various AAC(3) and APH(3’) isozymes tested only AAC(3)-IV and APH(3’)-Ia affect by apralogs 2 and 3 (Table 3). AAC(3)-IV affects both 2 and 3, but primarily the latter, while APH(3’)-Ia only affects 2. These features were also evident when we screened a panel of E. coli clinical isolates with acquired AAC(3) and APH(3’) resistance (Table 4). Overall, the Achilles heel of apramycin and 3 is AAC(3)-IV, while that of 2 is APH(3’)-Ia. Apralog 4 on the other hand retained high levels of activity in the presence of AAC(3) isozymes including AAC(3)-IV, whether in recombinant or clinical strains. These findings are particularly significant not only as AAC(3)-IV is the only AME known to act on the parent apramycin,[5] but also because they demonstrate the capability of enhancing the activity of the parent by introduction of a modified ribosyl-type substituent without incurring the penalty of susceptibility to APH(3’)-Ia seen in the comparator lividomycin B.

Table 3.

Antibacterial Activities Against Recombinant E. coli Strains Expressing Single Resistance Determinants in an Isogenic Background (MIC, mg/L)

| Resistance Determinant | wt parental | AAC(3)-IV | AAC(3)-II | APH(3’)-Ia | APH(3’)-IIa | APH(3’)-IIb | APH(3’)-VI | armA | rmtB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | EC026 | EC118 | EC200 | EC122 | EC123 | EC125 | EC141 | EC102 | EC103 |

| Apramycin | 2 | 128 | 2–4 | 1–2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0.5–1 | 4 | 0.5–1 | 2–4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 0.5–1 | 8–16 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5–1 |

| 4 | 0.25–0.5 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

Table 4.

Antibacterial Activities (MIC, mg/L) Against E. coli Strains with Acquired AAC(3) and APH(3’) Resistancea

| Resistance Determinant | wt | AAC(3)-II | AAC(3)-IV | APH(3’)-I | APH(3’)-II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | AG001 | AG170 | AG173 | AG163 | AG166 |

| Apramycin | 4 | 4–8 | 256 | 4 | 4–8 |

| Lividomycin B | 4–8 | 4–8 | 16 | >256 | 4–8 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4–8 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 2–4 | 2–4 |

| 4 | 1–2 | 1–2 | 4 | 1–2 | 1–2 |

Finally, we screened apralog 4 for activity against a small panel of clinical isolates of E. coli with two or more relevant resistance determinants (Table 5). It was found that 4 retains strong activity in the combined presence of both AAC(3)-IV and APH(3’)-I, as well as in the presence of combinations of AAC(3) and or APH(3’) isozymes with AAC(6’), the most prevalent resistance mechanism against the clinical AGA gentamicin, and the ribosomal methyltransferase RmtB, which completely abrogates the activity of all 4,6-type AGAs including gentamicin and plazomicin.

Table 5.

Antibacterial Activities (MIC, mg/L) Against E. coli Strains with Two or More Acquired Resistance Determinants.a

| Resistance Determinant | AAC(3)-IV, APH(3’)-I | AAC(3)-IV, APH(3’)-I | AAC(6’)-Ib, AAC(3)-IId | APH(3’)-Ia, AAC(3)-IId | AAC(3)-IIa, AAC(6’)-Ib, RmtB | AAC(3)-II, APH(3’)-II, RmtB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | AG182 | AG183 | AG157 | AG180 | AG341 | AG153 |

| Apramycin | >256 | >256 | 8 | 4 | 2–4 | 8 |

| 2 | 16 | 16–32 | 4 | 4 | 1–2 | 4 |

| 3 | 32 | 32–64 | 4 | 4 | 1–2 | 4 |

| 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 2–4 | 4 |

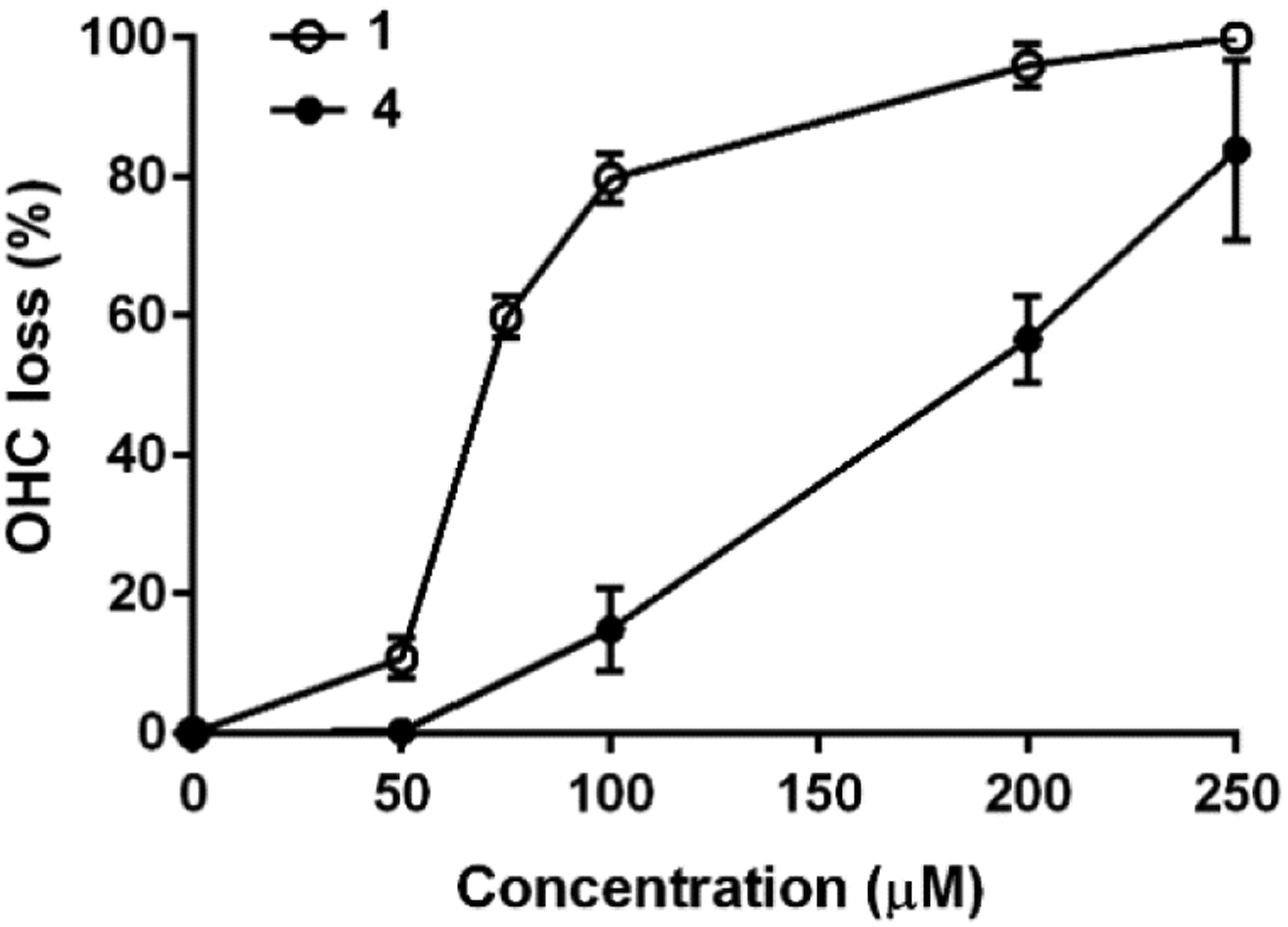

To assess potential ototoxicity, increasing concentrations of apralog 4 and the parent apramycin were incubated with cochlear explants from postnatal 3 day FVB/NJ mice for 72 h before staining and counting of outer hair cells (OHCs).[7c] Plotting the percentage of OHC loss against AGA concentration (Figure 4) then allowed the determination of the LD50 values. Apralog 4 showed an approximate of 2-fold reduction in cochleotoxicity (LD50 = 175 ± 19.2 μM) compared to apramcyin (LD50 = 71 ± 1.8 μM). This reduction of cochleotoxicity was achieved with only minor enhancement in mitoribosomal selectivity with respect to the parent (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Dose–response plots of the percentage of outer hair cell loss (OHC) versus concentration of aminoglycoside. Data are presented as mean values ± σ, n = 6–7 per point.

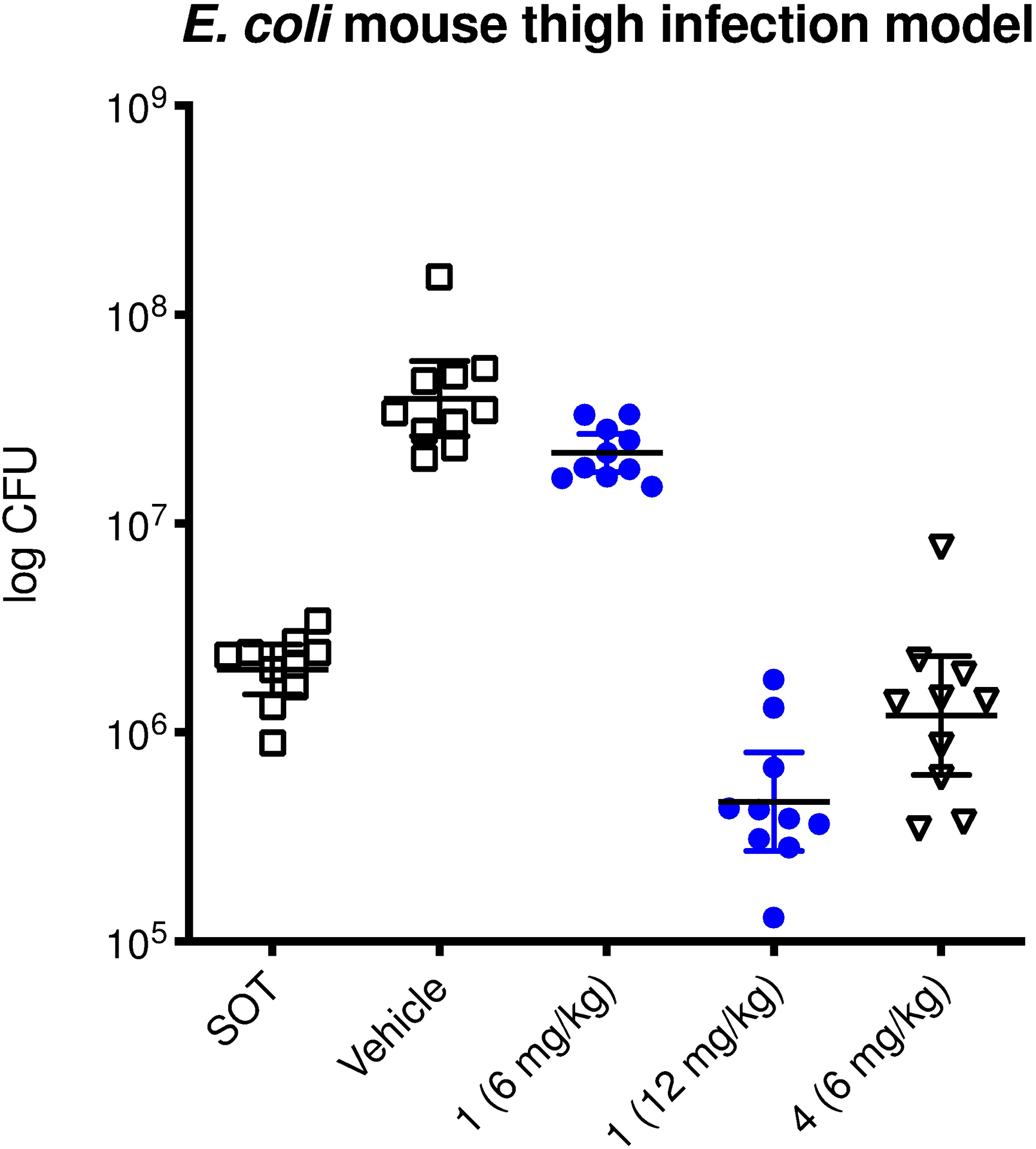

Finally, we turned to in-vivo efficacy for which we employed an E. coli mouse thigh infection model. At a dose of 6 mg.kg−1 apralog 4 reduced the bacterial burden in the blood by approximately 1 log unit, comparable to the parent at double the dose and significantly more than the parent at the same dose level (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

In-vivo efficacy of apralog 4 in comparison to apramycin (1) in a neutropenic mouse thigh infection model.

In conclusion, apralog 4 carrying a doubly modified β-D-ribofuranosyl substituent at the apramycin 5-position is obtained by a robust, convergent synthesis in only six steps from readily available apramycin. It displays significantly improved affinity for the bacterial decoding A site and similarly improved inhibition of the bacterial ribosome over the parent apramycin. This increased affinity and activity at the target level is reflected in significantly improved activity against multiple wild-type ESKAPE pathogens and both recombinant and clinical isolates of E. coli carrying one or more relevant resistance determinants. Thus, apralog 4 is not affected by the APH(3’)-Ia class of AMEs despite the presence of the ribofuranosyl ring and shows excellent activity in the presence of the AAC(3)-IV resistance determinant that constitutes the only known[5] mechanism of resistance to the parent. The increased levels of antibacterial activity are reflected in the increased efficacy in the E. coli mouse thigh model. Albeit for reasons that are not yet clear, apralog 4 shows reduced levels of toxicity toward mouse cochlear explants compared to the parent with its already low ototoxicity. These multiple attributes combine to make apralog 4 an ideal candidate for further development as a next generation aminoglycoside for the treatment of MDR Gram-negative and other bacterial infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the NIH (AI123352) for support of this work, Rabiul Islam, Wayne State University for assistance with the RNA footprinting, and Evotec for the in-vivo efficacy study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

SNH, AV, ECB, and DC are cofounders of and equity holders in Juvabis AG, a biotech start-up developing aminoglycoside antibiotics.

Supporting information for this article can be found under: https://doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.202000726.

References

- [1].a) Böttger EC, Crich D, ACS Infect. Dis 2020, 6, 168–172; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brennan-Krohn T, Manetsch R, O’Doherty GA, Kirby JE, Translational Res 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Takahashi Y, Igarashi M, Antibiotics J 2018, 71, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- [2].O’Connor S, Lam LKT, Jones ND, Chaney MO, J. Org. Chem 1976, 41, 2087–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Matt T, Ng CL, Lang K, Sha S-H, Akbergenov R, Shcherbakov D, Meyer M, Duscha S, Xie J, Dubbaka SR, Perez-Fernandez D, Vasella A, Ramakrishnan V, Schacht J, Böttger EC, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA 2012, 109, 10984–10989; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ryden R, Moore BJ, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 1977, 3, 609–613; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Juhas M, Widlake E, Teo J, Huseby DL, Tyrrell JM, Polikanov Y, Ercan O, Petersson A, Cao S, Aboklaish AF, Rominski A, Crich D, Böttger EC, Walsh TR, Hughes DE, Hobbie SN, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2019, 74, 944–952; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Galani I, Nafplioti K, Chatzikonstantinou M, Giamarellou H, Souli M, ECCMID 2018, P 0096; [Google Scholar]; e) Smith KP, Kirby JE, Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis 2016, 86, 439–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Magnet S, Blanchard JS, Chem. Rev 2005, 105, 477–497; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yang L, Ye XS, Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2010, 10, 1898–1926; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bacot-Davis VR, Bassenden AV, Berghuis AM, Med. Chem. Commun 2016, 7, 103–113; [Google Scholar]; d) Garneau-Tsodikova S, Labby KJ, Med. Chem. Commun 2016, 7, 11–27; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zárate SG, De ML, Claure la Cruz, Benito-Arenas R, Revuelta R, Santana AG, Bastida A, Molecules 2018, 23, 284, doi: 210.3390/molecules23020284; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Armstrong ES, Kostrub CF, Cass RT, Moser HE, Serio AW, Miller GH, in Antibiotic Discovery and Development (Eds.: Dougherty TJ, Pucci MJ), Springer Science+Business Media, New York, 2012, pp. 229–269; [Google Scholar]; g) Jospe-Kaufman M, Siomin L, Fridman M, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2020, 30, 127218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Plattner M, Gysin M, Haldimann K, Becker K, Hobbie SN, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2020, 21, 6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Brennan-Krohn T, Kirby JE, Antimicrob. Agent. Chemother 2019, 63, e01374–01319; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Doi Y, Wachino JI, Arakawa Y, Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am 2016, 30, 523–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Livermore DM, Mushtaq S, Warner M, Zhang J-C, Maharjan S, Doumith M, Woodford N, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2011, 66, 48–53; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cox G, Ejim L, Stogios PJ, Koteva K, Bordeleau E, Evdokimova E, Sieron AO, Savchenko A, Serio AW, Krause KM, Wright GD, ACS Infect. Dis 2018, 4, 980–987; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sonousi A, Sarpe VA, Brilkova M, Schacht J, Vasella A, Böttger EC, Crich D, ACS Infect. Dis 2018, 4, 1114–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ishikawa M, García-Mateo N, Čusak A, López-Hernández I, Fernández-Martínez M, Müller M, Rüttiger L, Singer W, Löwenheim H, Kosec G, Fujs S, Martínez-Martínez l., Schimmang T, Petković H, Knipper M, Duran-Alonso MB, Sci. Rep 2019, 9, 2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].https://www.imi.europa.eu/projects-results/project-factsheets/enable; accessed Feb 12, 2019.

- [10].a) Mandhapati AR, Shcherbakov D, Duscha S, Vasella A, Böttger EC, Crich D, ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 2074–2083; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Quirke JCK, Rajasekaran P, Sarpe VA, Sonousi A, Osinnii I, Gysin M, Haldimann K, Fang Q-J, Shcherbakov D, Hobbie SN, Sha S-H, Schacht J, Vasella A, Böttger EC, Crich D, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 530–544; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hu Y, Liu L, Zhang X, Feng Y, Zong Z, Front. Microbiol 2017, 8, 2275, doi: 2210.3389/fmicb.2017.02275; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kang AD, Smith KP, Eliopoulos GM, Berg AH, McCoy C, Kirby JE, Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis 2017, 88, 188–191; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zada SL, Baruch BB, Simhaev L, Engel H, Fridman M, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 3077–3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Abe Y, Nakagawa S, Naito T, Kawaguchi H, Antibiotics J 1981, 34, 1434–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Alper PB, Hendrix M, Sears P, Wong C-H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Hobbie SN, Akshay S, Kalapala SK, Bruell C, Shcherbakov D, Böttger EC, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA 2008, 105, 20888–20893; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hobbie SN, Bruell CM, Akshay S, Kalapala SK, Shcherbakov D, Böttger EC, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA 2008, 105, 3244–3249; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hobbie SN, Kalapala SK, Akshay S, Bruell C, Schmidt S, Dabow S, Vasella A, Sander P, Böttger EC, Nucl. Acids Res 2007, 35, 6086–6093; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Huth ME, Ricci AJ, Cheng AG, Int. J. Otolaryngol 2011, 937861; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Prezant TR, Agapian JV, Bohlman MC, Bu X, Öztas S, Qiu W-Q, Arnos KS, Cortopassi GA, Jaber L, Rotter JI, Shohat M, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Nat. Genetics 1993, 4, 289–294; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Böttger EC, Schacht J, Hearing Res 2013, 303, 12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wright GD, Thompson PR, Front. Biosci 1999, 4, d9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Raluy E, Pàmies O, Diéguez M, Adv. Synth. Catal 2009, 351, 1648–1670. [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Moazed D, Noller HF, Nature 1987, 327, 389–394; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Waduge P, Sakakibara Y, Chow CS, Methods 2019, 156, 110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.