Food insecurity (the economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food) has been associated with cardiovascular health in prior cross-sectional studies.1 Understanding the relationship between changes in food insecurity and the cardiovascular health of communities may help devise interventions that could improve community cardiovascular health. This is particularly important given reports of increasing food insecurity due to the coronavirus pandemic, and the stagnation of the decline in cardiovascular mortality rates among the non-elderly adult population in the U.S.

This analysis was considered exempt from review by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board as all data used are routinely collected and publicly available. All statistical code used will be made available on request. Using data from the National Center for Health Statistics, we determined county-level, annual, age-adjusted (to the 2000 U.S. census) cardiovascular mortality rates for non-elderly (20–64 years old) adults in the U.S. from 2011 to 2017. Annual, county-level food insecurity rates were obtained from the Map the Meal Gap project, which estimates county-level rates by using state-level rates and county-level economic and demographic factors.2 These food insecurity estimates are considered less reliable for the elderly population, therefore this population was not included. The following county-level variables were obtained for each year from 2011 to 2017: median household income, poverty rate, unemployment rate, high school graduation rate, housing vacancy rate, health insurance coverage rate, density of primary care providers, and density of hospital beds, and proportion of residents by gender, race, and ethnicity from publicly available sources (US Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Services, Health Resources and Services Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). We compared annual, age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality rates by quartiles of mean annual percent change in food insecurity. A Poisson fixed effects estimator with robust standard errors was used to estimate the longitudinal association between changes in food insecurity and cardiovascular mortality after adjusting for changes in the other time-varying covariates listed above. A fixed effects (or within) estimator analyzes longitudinal change in the dependent (the number of age-adjusted deaths from cardiovascular disease) and independent variables (food insecurity rate and all other time-varying covariates) within each subject and therefore controls for any observed and unobserved time-invariant confounders between subjects (counties in this analysis).3 We also performed an analysis stratified by baseline (2011) food insecurity quartiles. All mortality rates are per 100,000 individuals. All analyses were conducted using STATA 15.0. S.Y.W. and S.A.M.K. had full access to all data and are responsible for its integrity.

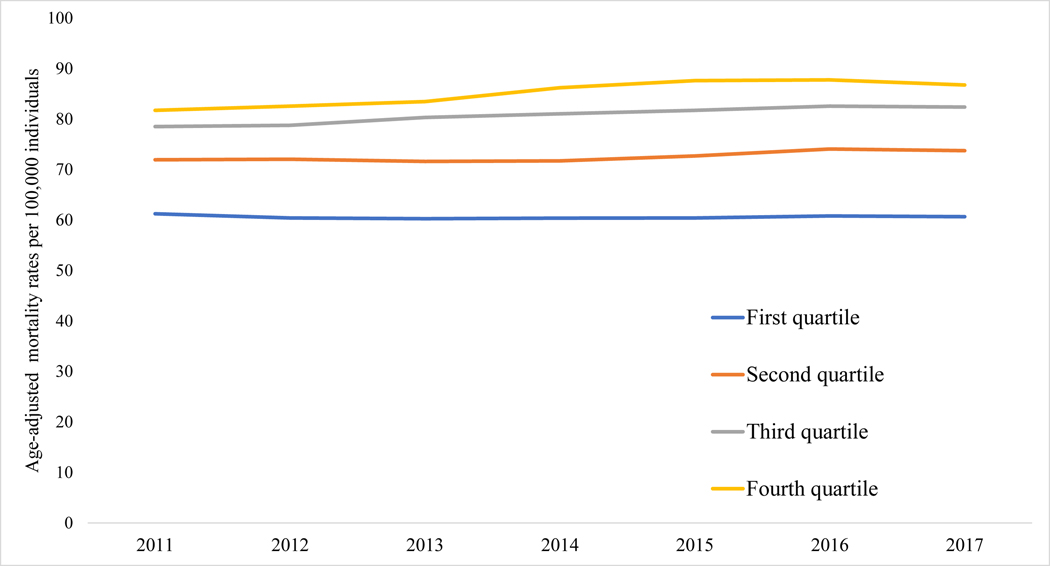

A total of 3,142 counties across all 50 states and Washington D.C. in the U.S. were included. Between 2011 and 2017, mean county-level food insecurity rates decreased from 14.7% to 13.3%. Mean annual percent change in food insecurity was −4.6% (SD=1.8) in the first (lowest) quartile, −2.1% (SD=0.4) in the second quartile, −0.85% (SD=0.4) in the third quartile, and 1.2% (SD=1.4) in the fourth (highest) quartile. Age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality rates did not change significantly between 2011 and 2017 in counties in the lowest quartile for mean annual percent change in food insecurity [61.2 (SD=21.8) to 60.7 (SD=22.6), p=0.97] (Figure 1). Mortality rates increased significantly in the other three quartiles: 72.0 (SD=28.6) to 73.4 (SD=31.0), p=<0.001 in the second quartile, 78.5 (SD=30.7) to 82.4 (SD=35.0), p=<0.001 in the third quartile, and 81.7 (SD=34.8) to 86.7 (SD=38.0), p<0.001 in the highest quartile. The multivariable Poisson fixed effects model estimated that a 1 percentage point increase in food insecurity was independently associated with a 0.83% (95% CI 0.43% to 1.25%, p<0.001) increase in age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality rates for non-elderly adults. When stratified by baseline food insecurity quartiles, this association was not statistically significant in the first [0.50% (95% CI −0.66% to 1.67%, p=0.41)] or second quartile [0.94% (95% CI −0.05% to 1.94%, p=0.06)] of baseline food insecurity, but was significant in the third [0.92% (95% CI 0.03% to 1.82%, p=0.04)] and fourth quartiles [0.76% (95% CI 0.23% to 1.31%, p=0.01)].

Figure 1: Annual age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality rates for 20 to 64 year old adults by quartile of mean annual percent change in county food insecurity rates between 2011 and 2017.

Estimated county-level food insecurity rates were obtained from the Map the Meal Gap project. Mean annual percent change in food insecurity is the mean of the annual percent change in food insecurity between each year over the study period.

From 2011 to 2017, an increase in food-insecurity in U.S. counties was associated with an increase in cardiovascular mortality rates for non-elderly adults, independent of changes in demographic, economic and healthcare access factors. Food insecurity may be associated with higher cardiovascular mortality by influencing the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension in a population, as well as by making medication adherence more difficult.4, 5 Our study’s limitations include possible unmeasured time-varying confounders, such as changes in other important economic factors, not accounted for in the longitudinal model. Due to the ecologic design, individual level inferences cannot be made.

County-level changes in food insecurity, independent of changes in other economic factors, may help identify counties at risk for worsening community level cardiovascular health. Whether interventions that improve food insecurity lead to improvements in community cardiovascular mortality needs to be further studied.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: Dr. Khatana is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1K23HL153772–01).

Footnotes

Disclosures: There are no other relevant financial disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article is published in its accepted form; it has not been copyedited and has not appeared in an issue of the journal. Preparation for inclusion in an issue of Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes involves copyediting, typesetting, proofreading, and author review, which may lead to differences between this accepted version of the manuscript and the final, published version.

References

- 1.Leung C, Tester J and Laraia B. Household Food Insecurity and Ideal Cardiovascular Health Factors in US Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:730–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gundersen C, Engelhard E and Waxman E. Map the meal gap: exploring food insecurity at the local level. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 2014;36:373–386. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunasekara FI, Richardson K, Carter K and Blakely T. Fixed effects analysis of repeated measures data. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seligman HK, Laraia BA and Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. The Journal of nutrition. 2010;140:304–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverman J, Krieger J, Kiefer M, Hebert P, Robinson J and Nelson K. The Relationship Between Food Insecurity and Depression, Diabetes Distress and Medication Adherence Among Low-Income Patients with Poorly-Controlled Diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1476–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]