Abstract

Purpose:

Sunscreen use provides ultraviolet radiation (UV) protection but is often limited in school settings because sunscreen is classified as an over-the-counter drug product. Some US states have laws allowing students to carry and self-apply sunscreen. We examined these laws in the context of state UV levels.

Methods:

We obtained legislative information through April 2020 from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association website and UV data for years 2005–2015 from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Environmental Public Health Tracking website.

Results:

Twenty-three states and District of Columbia have sunscreen laws, including 11 states with UV levels above the median UV level across states. There was no significant association between state UV levels and sunscreen laws.

Conclusions:

The presence of state sunscreen legislation has increased but is not associated with UV levels. Future research could examine the implementation and public health effects of these laws.

Keywords: Skin cancer, UV, Sunscreen, Sun-safety, Prevention, Schools

Exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation (UV) is an important skin cancer risk factor [1]. Major health organizations encourage using sunscreen with other protective strategies to minimize UV damage to skin while outdoors [1]. In the United States, the US Food and Drug Administration regulates sunscreen products as over-the-counter drug products [2]. School districts often have policies that limit students’ ability to carry and self-administer these products at school which can create barriers to sunscreen use among students [3,4]. To address this, 23 states have passed legislation permitting students to carry and self-apply sunscreen at school, influenced in large part by the advocacy efforts of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association (ASDSA) and their SUNucate coalition [3–5]. This study examines the presence of such legislation in context of annual average state UV levels.

Methods

The ASDSA website was our primary data source for state-level sunscreen legislation [3,4]. We also checked each state’s legislative website for corresponding legislative records and had 100% confirmation. All legislative data were current as of April 30, 2020. Although there are slight wording differences across states, the main purpose of each law is to allow students to carry and self-apply sunscreen at school. More information about this legislation is in Table 1, a previous content analysis [5], and on the ASDSA website [3,4].

Table 1.

State legislation allowing students to carry and self-apply sunscreen at school in the contiguous United States

Note: States that do not have legislation regarding sunscreen use in school include: Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, and Vermont. Alaska and Hawaii also do not have sunscreen laws in place but are not included in this article or this table because of the lack of available UV data for these states.

If a state has pending legislation, the year provided is the year the legislation was introduced.

Nebraska has a guidance document from the board of education but not passed or pending legislation.

UV data were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network (Tracking Network) website [6]. We used erythemally weighted daily dose of UV irradiance (EDD) (J/m2) for each state in the contiguous United States and the District of Columbia (D.C.) during 2005–2015. EDD is a measure of the accumulated amount of UV that can cause sunburn over the course of the day, which is then averaged for a given year to create the annual average EDD. The methods used to generate UV data were published previously [7]. We calculated the mean annual average EDD during 2005 and 2015 to create a single measure of UV for each state and D.C. We rank-ordered states by the calculated UV levels and coded each state as having a sunscreen law in place, having a sunscreen bill pending decision, or not having a sunscreen law or bill. We used a two-sample t-test to examine whether UV levels are significantly different in states with and without sunscreen legislation. Alaska and Hawaii were excluded because UV data were not available for these states.

Results

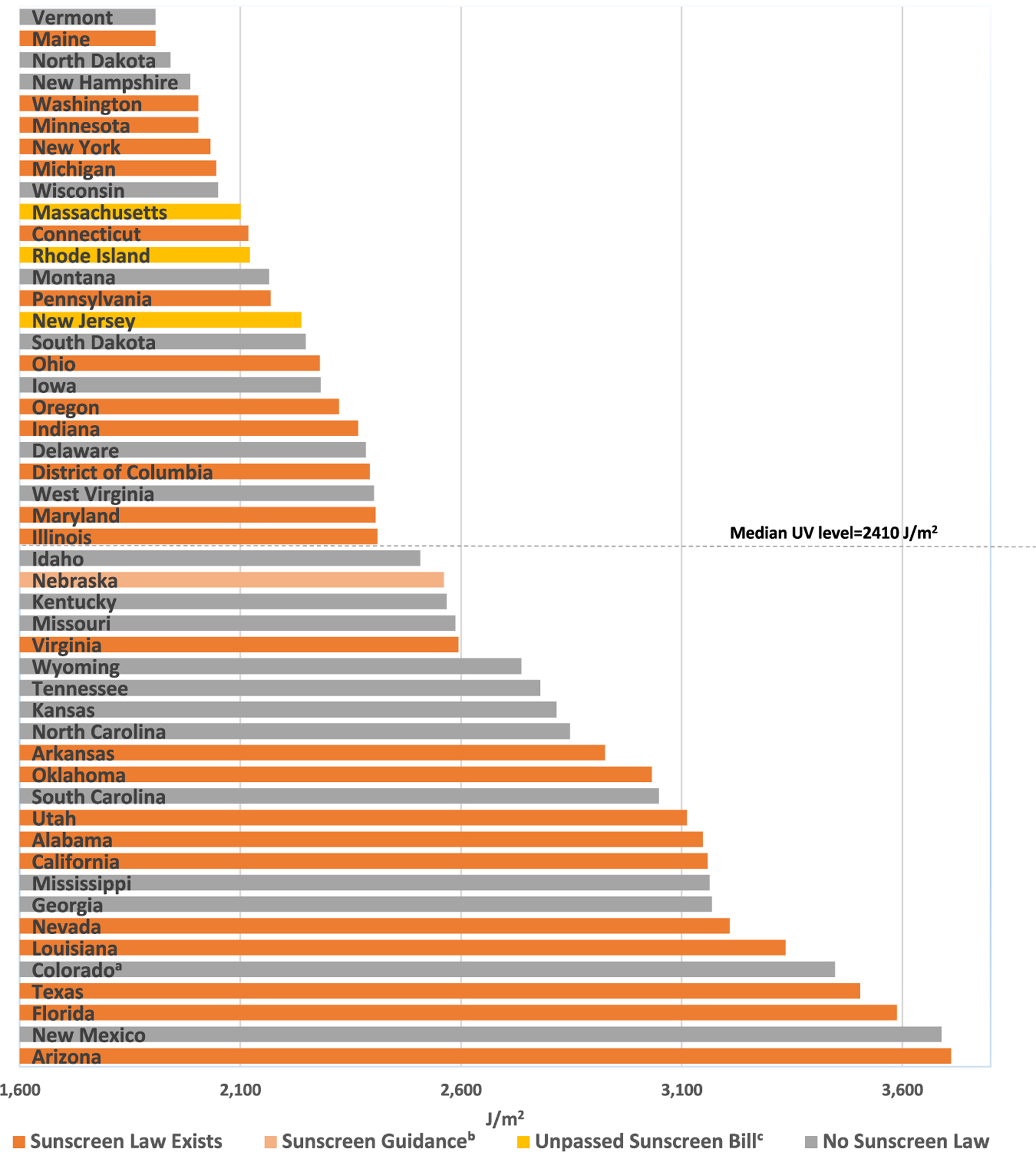

Twenty-three states and D.C. had passed sunscreen laws; three states had introduced sunscreen bills (Table 1). California was the first state to pass sunscreen legislation in 2002, and no states passed sunscreen legislation during 2002–2012. During 2013-April 2020, 22 other states and D.C. passed sunscreen legislation, and Nebraska’s State Board of Education provided guidance allowing sunscreen use in schools. Annual average UV levels ranged from 1908 J/m2 to 3710 J/m2 (Figure 1). Among the 24 states with UV levels above the median (as shown by the dotted line in Figure 1), 11 had sunscreen laws, and one had a guidance document. Among the 24 states with UV levels below or at the median, 12 states and D.C. had sunscreen laws, and three states had bills pending decision. There was no statistically significant association between state UV levels and sunscreen laws (p = .736).

Figure 1.

Annual average UV levels measured in erythemally weighted daily dose (EDD) (J/m2) from 2005 to 2015 in the contiguous United States, by state. aAlthough Colorado does not have a law in place allowing students to use sunscreen at schools, there is a regulation in place allowing children to possess and use sunscreen in child care centers and day camps (https://www.sos.state.co.us/CCR/GenerateRulePdf.do?ruleVersionId=973). bSunscreen Guidance refers to the guidance document produced by the Nebraska State Board of Education promoting sunscreen use in schools. cUnpassed sunscreen bills are proposed laws pending decision in the state legislature. dAlaska and Hawaii are not included in this graph because the National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network did not include their data.

Discussion

The number of US states with school sunscreen laws has increased substantially since 2013. Half of the states we examined did not have sunscreen legislation or guidance in place, including some states with UV levels above the median. The presence of sunscreen legislation was not significantly associated with state UV levels. Cumulative UV exposure throughout life, including during childhood, increases skin cancer risk. Given children are in school for many years, the exposure experienced while at school has potential to play an important role in their overall risk.

UV data provided by the Tracking Network could be useful when planning and prioritizing skin cancer–prevention interventions at state or local level. It is worth noting that UV levels sometimes vary greatly within a given state, and county-level UV data available in the Tracking Network could be used for more tailored risk assessment. Previous research findings associated county-level solar UV levels with melanoma incidence among non-Hispanic white US adults [1,8]. EDD data for UV levels include summer months, when students are not in school and are potentially less hindered by school regulations. In addition, sunscreen is most effective when used in combination with other sun-safety strategies (e.g., shade, protective clothing, scheduling outdoor activities to avoid times of peak UV.)

Findings from a recent survey from Minnesota suggest parents may be particularly supportive of laws allowing sun-safe behaviors such as sunscreen use at school [9]. Future research could further examine awareness of school sunscreen policies among students, parents, and school staff and explore variations in the policy implementation within and between states. It would also be informative to explore if and when districts are able to make exceptions to the existing state policies, as this is a gap in the understanding of this policy.

The national Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) monitors general sunscreen use (not specific to school settings) among high school students [10]. The most recent national YRBS data (from 2013) indicated that only about one in 10 high school students regularly wore sunscreen with an sun protection factor of 15 or higher when outside for more than 1 hour on a sunny day [10]. The 2019 national YRBS will provide new data on general sunscreen use among US high school students, allowing for comparisons before and after most laws were passed. Future research could also investigate the relationship between the presence of sunscreen laws and indoor tanning age restrictions within states.

In conclusion, less than half of US states had sunscreen legislation or guidance in place as of April 2020. The presence of sunscreen legislation was not significantly associated with UV levels. Future research could examine awareness, implementation, and potential public health effects of state laws to improve sunscreen access in schools.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

This article examines the presence of sunscreen legislation in the context of state ultraviolet radiation levels. Findings suggest opportunities for additional efforts to facilitate sunscreen access in school settings. Research on awareness, implementation, and the potential public health impact of state sunscreen laws could inform policy and practice.

Funding Sources

B.P.’s work on this project was funded by the Jeff Metcalf Internship Program and First-Year Odyssey Career Program at the University of Chicago. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent skin cancer. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Sunscreen. How to help protect your skin from the sun Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/understanding-over-counter-medicines/sunscreen-how-help-protect-your-skin-sun. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- [3].SUNucate protecting the public from skin cancer. Available at: https://sunucate.org/about/. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- [4].American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association. SUNucate website. Available at: https://www.asds.net/asdsa-advocacy/advocacy-activities/sunucate. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- [5].Patel RR, Holman DM. Sunscreen use in schools: A content analysis of US state laws. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;79:382–4. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network. Data explorer Available at: https://ephtracking.cdc.gov/DataExplorer. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- [7].Zhou Y, Meng X, Belle JH, et al. Compilation and spatio-temporal analysis of publicly available total solar and UV irradiance data in the contiguous United States. Environ Pollut 2019;253:130–40. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Richards TB, Johnson CJ, Tatalovich Z, et al. Association between cutaneous melanoma incidence rates among white US residents and county-level estimates of solar ultraviolet exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;65: S50–7. 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kozlowski A, Dodd E, Hanson B, et al. Parental support for sun-protection policies in schools: A cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 81:1420–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. Youth risk behavior Surveillance – United States, 2013. MMWR 2014;63:41–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]