Abstract

Purpose of review

Using case vignettes, we highlight challenges in communication, prognostication, and medical decision-making that have been exacerbated by the coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic for patients with kidney disease. We include best practice recommendations to mitigate these issues and conclude with implications for interdisciplinary models of care in crisis settings.

Recent findings

Certain biomarkers, demographics, and medical comorbidities predict an increased risk for mortality among patients with COVID-19 and kidney disease, but concerns related to physical exposure and conservation of personal protective equipment have exacerbated existing barriers to empathic communication and value clarification for these patients. Variability in patient characteristics and outcomes has made prognostication nuanced and challenging. The pandemic has also highlighted the complexities of dialysis decision-making for older adults at risk for poor outcomes related to COVID-19.

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic underscores the need for nephrologists to be competent in serious illness communication skills that include virtual and remote modalities, to be aware of prognostic tools, and to be willing to engage with interdisciplinary teams of palliative care subspecialists, intensivists, and ethicists to facilitate goal-concordant care during crisis settings.

Keywords: communication, coronavirus, kidney, palliative, prognostication

INTRODUCTION

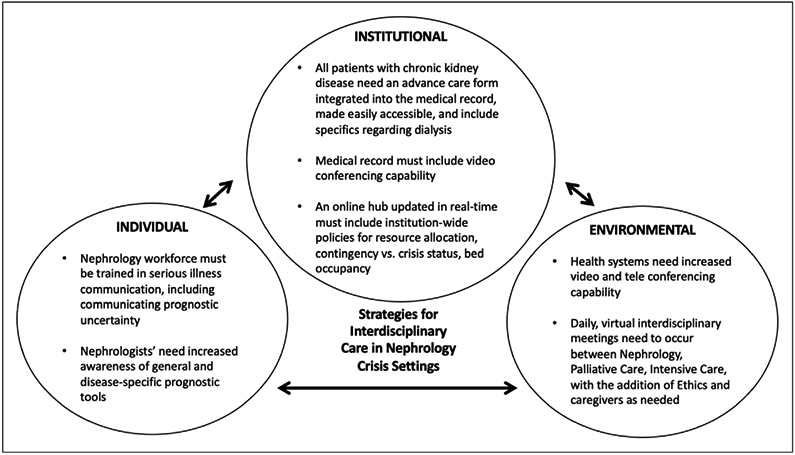

The coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic has thus far resulted in over 300,000 lives lost in the United States [1]. Patients with kidney disease are at greater risk for adverse health outcomes in the setting of COVID-19 [2]. In addition to having to manage medically complex, critically ill patients, nephrologists caring for patients with COVID-19 face novel diagnostic dilemmas and psychological stressors. We describe three case vignettes of patients with kidney disease and COVID-19 to highlight challenges in communication, prognostication, and dialysis decision-making that have been exacerbated by this crisis. We include resources (Table 1) and a framework of suggestions (Fig. 1) to mitigate these challenges with a focus on interdisciplinary collaboration between nephrologists, palliative care subspecialists, intensivists, and ethicists that can be applied to future crisis settings.

Table 1.

Resources to enhance communication, prognostication, dialysis decision-making, and interdisciplinary collaboration in COVID-19 and crisis settings

| Topic | Resource (Reference Number) |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| Serious illness communication resources | Mandel et al. serious illness conversation guide [55] | Multistep guide for patients with kidney disease: Set up conversation Assess illness understanding and information preferences Explore key topics Close conversation Document Includes patient-tested language for each step |

| VitalTalk COVID Ready Communication Playbook [56] | Practical advice with short suggested scripts and ‘talking maps’ on how to discuss difficult topics related to COVID-19 General to all populations and specialties |

|

| VitalTalk COVID-ready communication skills for Nephrology [11] | Practical communication strategies specific to nephrology Table of suggested wording and replies for nephrology specific COVID topics |

|

| The Ask-Tell-Ask approach to conversations with seriously ill patients with kidney disease [57] | Downloadable pocket card with nephrology specific language for guiding goals of care conversations with patients with kidney disease Includes reminder of Medicare billing codes for advance care planning Video demonstration of Ask-Tell-Ask conversation with simulated patient |

|

| Communicating prognostic uncertainty | Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients and Pathways Project [58] | Strategies to respond to difficult questions and emotional distress related to COVID-19 prognosis in the setting of end-stage kidney disease |

| VitalTalk Discussing Prognosis [34] | Multistep process for general populations:s Assess patient understanding Determine what information patient wishes to know Anticipate ambivalence Provide information Track and validate emotion |

|

| Back et al. Oncology conversation guide [32] | Multistep process for cancer populations with ambivalence toward prognostic understanding: Identify cause of ambivalence Acknowledge informational and emotional concerns Assess whether patient’s prognostic understanding will change treatment decision-making Explore pros and cons of prognostic awareness for the patient Acknowledge difficulty of the situation Outline options for knowledge revelation and their consequences |

|

| Prognostic tools for patients with kidney disease | Cohen et al. Six-Month Mortality Predictor for Hemodialysis [27] | Surprise question (would you be surprised if this patient died in the year? Albumin level (g/L) Age (years) Dementia? Peripheral vascular disease? |

| Couchoud et al. Six-Month Mortality Predictor for Adults > 75 years receiving Hemodialysis [28] | Body mass index < 18.5 kg/m2 Diabetes mellitus? Class 3 or 4 congestive heart failure? Stage 3 or 4 peripheral vascular disease? Dysrhythmia? Active malignancy? Severe behavioral disorder? Total dependency for transfers? Unplanned dialysis |

|

| Moss et al. 1-Year Mortality Predictor for Hemodialysis [29] | Surprise question (would you be surprised if this patient died in the year?) | |

| Beddhu et al. Charlson Comorbidity Index predictor for hospital admissions, hospital length of stay, and costs in patients receiving dialysis [30] | Coronary artery disease Congestive heart failure Peripheral vascular disease Cerebrovascular disease Dementia Chronic pulmonary disease Connective tissue disorder Peptic ulcer disease Mild liver disease Diabetes Hemiplegia Moderate or severe kidney disease Diabetes with end-organ damage Any tumor, leukemia, lymphoma Moderate or severe liver disease Metastatic solid tumor Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome |

|

| Health systems strategies to enhance virtual communication between patients and providers | American Medical Association telehealth guide [16] | Step-by-step guide in processes and implementation for telehealth platform that is embedded into health system, including key stakeholder engagement for sustainability |

| American Academy of Family Physicians telemedicine toolkit [17] | ||

| Advance Care Planning resources | National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization list of Advance Directives by state [59] | State-by-state copies of Advance Directives |

| PREPARE [60] | Easy to read advance directive forms available for every state and multiple languages | |

| Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) by State [61] | State-by-state guidance on status of adoption of POLST | |

| Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients [62] | My Way (Make Your Wishes About You) – advance care plan information for people with chronic kidney disease | |

| Shared decision-making resources useful in crisis settings | Colorado Program for Patient-Centered Decisions COVID-specific decision aid [63] | One-page decision aid using simple language and images that focuses on ventilation |

| Individual and institutional crisis action plans | Conservative Kidney Management Crisis Action Plan [64] | Specific to patients with kidney disease; focuses on listing emergency contacts and list of medications including action plans for dosing in the setting of symptom distress |

| Hastings Center Recommendations for Healthcare Institutions responding to COVID-19 [65] | Discusses questions for administrators and clinicians to be considered as part of real-time reflection, review duties of healthcare leaders during a crisis setting, provides detailed guidelines for rapid ethics consultation and collaboration |

FIGURE 1.

Recommendations for Interdisciplinary Model of Care in Nephrology Crisis Settings.

CASE #1: CHALLENGES IN COMMUNICATION

DB is a 60-year-old Spanish-speaking man with hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and morbid obesity who you are caring for in the hospital. He has had three days of fevers and worsening respiratory distress and ultimately tests positive for acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-Co-V-2). His family cannot stay with him due to visitor restrictions. Over the next day, you transfer him to the intensive care unit (ICU) where he is intubated, sedated, proned, and begun on continuous kidney replacement therapy. The team makes daily contact with DB’s family with an interpreter. The family requests the team to do ‘everything to try to save him,’ but emphasizes that long-term dialysis is something he would not have wanted. Due to his persistent multiorgan failure, DB’s chance for survival appears low. His family asks you, ‘Can we see him?’ You work with hospital staff to arrange for DB’s family to see him through an electronic tablet. After ongoing conversations with you both via telephone and video, DB’s family makes the decision to transition him to conservative management. They are only allowed to enter his room during the last few days of his life, and DB soon succumbs to his illness.

Throughout the world, clinicians are experiencing challenges in communication with families in the setting of COVID-19. Family visitation has been either eliminated or restricted to specific circumstances, such as visits at the end of life [3,4]. Surges in patient volume and case complexity have made it difficult for clinicians to regularly communicate with families. To facilitate these challenging conversations, teams have increased engagement with palliative care subspecialists during COVID-19. These providers are specifically trained in empathic communication and value clarification in serious illness [5]. Although palliative care subspecialists provide critical assistance to clinicians and families with regards to assessing prognostic perceptions and forming goals of care decisions, they are a limited workforce [6]. The pandemic has emphasized that now, more than ever, all clinicians caring for patients with complex medical conditions need serious illness communication skills training. Such programs co-developed by nephrologists and palliative subspecialists improve knowledge and self-efficacy in discussing prognosis and delivering bad news, and many nephrology training programs have begun to incorporate serious illness communication skills training into their curriculums [7-10]. Components of these programs are available online and now include COVID-specific communication scripts applicable to patients with kidney disease ([11], Table 1). These scripts emphasize methods to allay fear, communicate uncertainty, and prepare families for the possibility of resource allocation.

An added challenge to DB’s case is his need for a language interpreter. In the United States, ~25 million individuals report limited English proficiency [12]. The Affordable Care Act has mandated that any healthcare system receiving federal assistance must provide individuals with limited English proficiency with a qualified interpreter; however, recent analyses demonstrated that fewer than 70% of hospitals are equipped to provide this type of language-concordant care [13,14]. Utilization of these resources has been more constrained during the COVID-10 pandemic.

Many hospitals have developed methods for telephone and/or video communication that are embedded into the health system that allow providers to speak to patients via secure tablet computers in real-time [15]. Incorporating interpreters into these systems-level strategies may improve barriers to effective communication during the pandemic that can be applied to patients with kidney disease. Healthcare systems have also incorporated virtual, interdisciplinary rounds that consist of Intensivists, pharmacists, social workers, and other allied health professionals that allow for real-time order input into the electronic health record [15]. Nephrologists could engage in these conferences when caring for critically ill patients with COVID-19 and in future crisis settings. Virtual, interdisciplinary conferences with palliative care subspecialists, intensivists, and even caregivers can create a platform for knowledge sharing and collaboration that is scalable within and across health systems. Society recommendations, resources, and guidelines exist for embedding teleconferencing capabilities within a health system ([16,17], Table 1). In DB’s case, due to a lack of teleconferencing capability and availability of a Spanish interpreter, his family was unable to communicate with him when he was still conscious.

CASE #2: CHALLENGES IN PROGNOSTICATION

SP is a 39-year-old woman with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) admitted to an urban safety net hospital for respiratory distress due to COVID-19. Though she was initially doing well, ****SP”s hospital course was complicated by worsening respiratory failure and an acute pulmonary embolism requiring admission to the ICU. When evaluating her, you note that she is requiring high flow nasal cannula and becoming increasingly tearful. ‘I’m scared,’ she admits. SP has no prior documentation of an Advance Directive and asks you to update her brother, her surrogate decision-maker, regarding her clinical condition. SP soon requires mechanical ventilation and is no longer able to communicate for herself. You call SP’s brother, who asks, ‘Do you think my sister will survive?’

SP’s case exemplifies the nuances and challenges of prognostication for patients with kidney disease or acute kidney injury in the setting of COVID-19. Evidence supports that SP’s ESKD, comorbid diabetes, and severity of respiratory distress place her at increased risk for mortality due to COVID-19 pneumonia [18]. Among patients with ESKD and COVID-19, mortality rates approach 31% [19,20], but the considerable clinical heterogeneity and geographic variability of published data have made it challenging for nephrologists to prognosticate meaningfully. Given that SARS-Co-V-2 pathogenesis in humans is still fairly recent, validated prognostic scores for ESKD are likely less relevant. As SP is neither an older adult nor obese, two known risk factors for mortality in COVID-19, her prognosis is uncertain.

Effective prognostication requires two steps. The first involves estimating a patient’s prognosis, and the second involves communicating this estimate to patients and families in language that is meaningful [21]. Physicians often prognosticate inaccurately and report discomfort in discussing their conclusions with patients and families, thus hindering both steps in this process [22]. These concerns are amplified in situations of prognostic uncertainty. Discomfort with communicating uncertainty is cited as justification to forgo engagement of patients and families in discussions of prognosis. This has been characterized as a ‘collusion of silence,’ in which physicians avoid discussing prognosis entirely, or speak in jargon with use of vague terms that are often unclear to patients and families [23]. Patients with kidney disease and their families yearn for these conversations and appreciate transparency and early preparation for possible end-of-life situations, but nephrologists have been shown to have significant discordance between their prognostic estimates and that of their patients [24,25]. In a survey of 584 Canadian patients with advanced CKD, 90% of respondents expressed a desire know about their prognosis, yet <10% reported having a conversation with their nephrologist about their prognosis [26].

Clinicians are accustomed to practicing with a large amount of data to formulate a prognosis, but nephrologists caring for patients with COVID-19 often do not have these resources. Currently, no disease-specific predictive models exist that estimate the chance of survival or need for kidney replacement therapy among adults with kidney disease and COVID-19, leaving nephrologists without the usual tools they bring to bedside care ([27-30], Table 1). Existing communication frameworks in nephrology and other chronic diseases outline the following steps to communicating prognostic uncertainty: naming that uncertainty exists, recognizing one’s own emotional response, validating patients’ emotional responses, addressing whether patients have concerns about their uncertain futures, providing information in small portions, and using ‘teach-backs,’ or communication strategies used to confirm patients’ understanding of information that was just provided to them [31-38]. To answer SP’s brother, one must validate his distress, express empathy regarding her clinical condition, and provide assurance that medical team will strive to meet her goals. SP ultimately decompensated overnight and experienced a cardiac arrest. Though she had remained ‘full code,’ she was unable to be resuscitated. SP’s brother, though devastated, appreciated the team’s consistent communication and had felt prepared for the possibility of a poor outcome.

CASE #3: CHALLENGES IN DIALYSIS DECISION-MAKING FOR OLDER ADULTS

HS is an 82-year-old man with mild cognitive impairment followed in your nephrology clinic for CKD over the past four years. He lives at home with his wife of 60 years and had been independent in all activities of daily living until a fall six months ago. Since then, HS has required a walker and needs assistance with dressing and toileting, all provided by his wife. At his last visit to the clinic, his estimated glomerular filtration rate had fallen to 12 mL/min/1.73m2. HS had found the Advance Directive forms specific to his state of residence confusing to interpret and thus has not formalized an advance care plan. During the visit, HS’s wife preferred to ‘not give up quite yet.’ HS emphasized that he wishes to ‘die peacefully in my own bed when the time comes.’ More recently, HS has become more dyspneic and visibly distressed. He has refused to present to the Emergency Department due to a fear of being exposed to COVID-19. HS’s wife calls you for advice on what to do. You manage to arrange a three-way call with HS’s son, who states that his father ‘would not want to be hooked up to machines.’ HS’s wife, however, makes it clear that she can’t bear to see her husband struggle to breathe. Throughout this time, HS has been too exhausted to participate in discussions to make his current wishes known.

HS’s case highlights a number of challenges related to dialysis decision-making magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic. HS’s difficulty in formalizing an advance care plan due to perceptions of the complexity of existing advance directives has been described in patients with other chronic medical conditions, and these forms continue to be completed at low rates in the United States [39]. Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) and Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) forms, usually briefer than an Advance Directive, may facilitate timely goal concordant care in nephrology crisis settings [40,41]. According to the state in which the form is being used, a POLST or MOLST may contain instructions related to dialysis decision-making that physicians can adhere to, even in the absence of a formalized Advance Directive. Nephrologists should make every effort to ensure that a POLST or Advance Directive care plan is easily accessible and integrated into the medical record of any outpatient they care for with advanced CKD.

HS’s prior ambivalence regarding chronic dialysis, lack of a formalized Advance Directive, and discordance between his desires and that of his loved ones highlight the need to fully facilitate exploration of his options and development of a realistic plan for dealing with likely escalation of care needs. Sending HS directly to the Emergency Department places him at the risk of being started on emergent dialysis and other life-sustaining measures that may not align with his goals and values. Furthermore, like HS, many older adults have purposely avoided accessing medical care in the COVID-19 pandemic, either in the hospital or through in-home services [42]. The key to caring for patients like HS is providing services that are responsive to their preferences, which may require development of care models not currently available in many communities. These include palliative care telehealth consultation to provide an in-home management plan for breathlessness, enhanced by further telehealth discussion to discuss conservative kidney management or a time-limited trial of dialysis.

HS’s case also highlights one ethical principle relevant to the care of patients with kidney disease in the COVID-19 pandemic: respect for autonomy. Patient autonomy allows for an individual to make decisions that align with his or her moral framework, unencumbered by the needs or perspectives of others [43,44]. Nephrologists aim to preserve patient autonomy by engaging with their patients in shared decision-making [45], but the pandemic has limited in-person ambulatory care provision frequency of ambulatory visits that may have otherwise made these conversations more feasible [46].

Creative models allowing for increased availability of palliative care consultation in emergency department and hospitals have been established during the initial COVID-19 surge [47-49]. Virtual modes of shared decision-making, as highlighted in HS’s case, may be the way forward in nephrology crisis settings during which in-person conversations cannot occur. Shared decision-making via telemedicine for individuals with other chronic medical conditions and limited healthcare access is feasible, acceptable, and reduces healthcare costs [50]. Depending on specific circumstances and the acuity of the situation, virtual shared decision-making may also allow for the assignment of a surrogate decisionmaker and a team-based approach to care between nephrologists, palliative care subspecialists, intensivists, and even ethicists. Older patients with kidney disease and COVID-19 may lack decision-making capacity due to cognitive impairment and critical illness, complicating efforts to determine plans of care that align with patient values [51,52]. The removal of restrictions on telemedicine services by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services may continue to spur the use of virtual modalities to foster timely and potentially rapid shared decision-making. Providers can waive Medicare copayments for telehealth services, including behavioral health counseling and occupational therapy [53]. In HS’s case, a shared decision to forgo dialysis was made via a video conferencing call with his wife and son.

CONCLUSION

Nephrologists have faced extraordinary challenges in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2013, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a toolkit for health systems leaders involved in a crisis setting [54]. Strategies for success included engagement of provider stakeholders across multiple subspecialties, clear assignments of responsibility and leadership roles, evidence-based clinical operations, quality metrics for sustained implementation, and culture change. Informed by the IOM toolkit, we conclude with suggestions for specific strategies to address these challenges at the individual, environmental, and institutional level (Fig. 1). Engaging in serious illness communication skills training, finding creative ways to circumvent physical barriers to goal-directed communication, communicating prognostic uncertainty, documenting advance directives in a timely fashion, using telemedicine for virtual shared decision-making, and collaborating with interdisciplinary teams to uphold goal concordant care are difficult but worthy challenges to overcome for patients living with kidney disease during times of crisis.

KEY POINTS.

Health systems can consider increasing the availability of modes of virtual communication for hospitalized, critically ill patients with kidney disease that include language interpreters.

Nephrologists may benefit from serious illness communication skills training, including strategies to communicate prognostic uncertainty.

Nephrologists may benefit from continued awareness of existing prognostic tools to help them provide prognostic information to families in language that is meaningful.

Forms related to advance care planning in nephrology may benefit from including specifics related to dialysis decision-making and made accessible in the electronic medical record of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease.

Daily interdisciplinary virtual conferences between nephrologists, palliative care specialists, intensivists, and ethicists and caregivers may facilitate goal concordant care and communication.

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)/Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Learning Health Systems K12HS026395 to DN

National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) K23125840 to JSS

National Kidney Foundation (NKF) Young Investigator Grant to JSS

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Grant to DL

Patrick And Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation Grant to DL

Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients Grant to DL

This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any funding institution.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Provisional death counts for Coronavirus Disease 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/index.htm. [Accessed 9 September 9 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajaimy M, Melamed ML. COVID-19 in patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 15:1087–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hospital Visitation Guidelines for 2020. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-hospital-visitation-phase-ii-visitation-covid-negative-patients.pdf. [Accessed 1 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Workplace personal protective equipment and supply chain issues. National Safety Council. Available ****at” https://www.nsc.org/Portals/0/Documents/NSCDocuments_Advocacy/Safety%20at%20Work/covid-19/safer/qh-supply-chain2.pdf. [Accessed 1 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruera E, Billings JA, Lupu D, et al. AAHPM position paper: requirements for the successful development of academic palliative care programs. J Pain Symptom Manag 2010; 39:742–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lupu D. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manag 2010; 40:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schell JO, Arnold RM. NephroTalk: communication tools to enhance patient-centered care. Semin Dial 2012; 25:611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Combs SA, Culp S, Matlock DD, et al. Update on end-of-life care training during nephrology fellowship: a cross-sectional national survey of fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 65:233–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelfand SL, Schell JO, Eneanya ND. Palliative care in nephrology: the work and the workforce. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2020; 27:350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair D, El-Sourady M, Bonnet K, et al. Barriers and facilitators to discussing goals of care among nephrology trainees: a qualitative analysis and novel educational intervention. J Palliat Med 2020; 23:1045–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sciacca K, Tulsky J, Lakin J. COVID-ready communication skills for nephrology. VitalTalk. Available at: https://www.vitaltalk.org/wp-content/uploads/Nephrology-COVID-Communication_KidneyPal-1.pdf. [Accessed 20 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Language data. United States Census Bureau. Available at: https://www.census.gov/topics/population/language-use/data.html. [Accessed 1 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Limited English proficiency. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/special-topics/limited-english-proficiency/index.html. [Accessed 20 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiaffino MK, Al-Amin M, Schumacher JR. Predictors of language service availability in U.S. hospitals. Int J Health Policy Manag 2014; 3:259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwamm LH, Estrada J, Erskine A, Licurse A. Virtual care: new models of caring for our patients and workforce. Lancet Digital Health 2020; 2:e282–e285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Telehealth quick guide. American Medical Association. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/ama-telehealth-quick-guide. [Accessed 25 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 17.A toolkit for building and growing a sustainable telehealth program in your practice. American Academy of Family Physicians. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/telehealth/2020-AAFP-Telehealth-Toolkit.pdf. [Accessed 25 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller LE, Bhattacharyya R, Miller AL. Diabetes increases the mortality of patients with COVID-19. Medicine 2020; 99:e22439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guangchang P, Zhiguo Z, Peng J, et al. Renal involvement and early prognosis in patients with COVID-19 and pneumonia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 31:1157–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robbins-Juarez SY, Qian L, King KL, et al. Outcomes for patients with COVID-19 and acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. KI Rep 2020; 5:1149–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwashyna TJ, Christakis NA. Physicians, patients, and prognosis. West J Med 2001; 174:253–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krawczyk M, Gallagher R. Communicating prognostic uncertainty in potential end-of-life contexts: experiences of family members. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han PK. The need for uncertainty: a case for prognostic silence. Perspect Biol Med 2016; 59:567–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: a systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important. Palliat Med 2015; 29:774–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:1206–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen LM, Ruthazer R, Moss AH, Germain MJ. Predicting six-month mortality for patients who are on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Couchoud C, Labeeuw M, Moranne O, et al. A clinical score to predict 6-month prognosis in elderly patients starting dialysis for end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24:1553–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the ‘surprise’ question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3:1379–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beddhu S, Bruns FJ, Saul M, et al. A simple comorbidity scale predicts clinical outcomes and costs in dialysis patients 2000; 108:609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parvez S, Abdel-Kader K, Song MK, Unruh M. Conveying uncertainty in prognosis to patients with ESRD. Blood Purific 2015; 39:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Back AL, Arnold RM. Discussing prognosis: ‘how much do you want to know?’ talking to patients who do not want information or who are ambivalent. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24:4214–4217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorsteinsdottir B, Germain MJ. The role of estimating and communicating prognosis in kidney supportive care. In: Palliative care in nephrology. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; c2020. 127–36. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Discussing Prognosis. Vital Talk. Available at: https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/discussing-prognosis/. [Accessed 25 September 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, et al. Discussing conservative management with older patients with CKD: an interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis 2018; 71:627–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor LJ, Nabozny MJ, Steffens NM, et al. A framework to improve surgeon communication in high-stakes surgical decisions: best case/worst case. JAMA Surg 2017; 152:531–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grubbs V. Time to recast our approach for older patients with ESRD: the best, the worst, and the most likely. Am J Kidney Dis 2018; 71:605–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibbon LM, GrayBuck KE, Buck LI, et al. Development and implementation of a clinician-facing prognostic communication tool for patients with COVID-19 and critical illness. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020; 60:e1–e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff 2017; 36:1244–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guidance for health professionals to identify appropriate patients for POLST. National Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST). Available at: https://polst.org/professionals-page/?pro=1. [Accessed 24 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MOLST Form. Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment. Available at: https://molst.org/how-to-complete-a-molst/molst-form/. [Accessed 29 October 2020]

- 42.Bianchetti A, Bellelli G, Guerini F, et al. Improving the care of older patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020; 32:1883–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of biomedical ethics: marking its fortieth anniversary. Am J Bioeth 2019; 19:9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin DE, Parsons JA, Caskey F, et al. Ethics of kidney care in the era of COVID-19. Kidney Int 2020; 98:1424–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eneanya ND, Goff SL, Martinez T, et al. Shared decision-making in end-stage renal disease: a protocol for a multicenter study of a communication intervention to improve end-of-life care for dialysis patients. BMC Palliat Care 2015; 14:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaker MS, Oppenheimer J, Grayson M, et al. COVID-19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8:1477–1488e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ankuda CK, Woodrell CD, Meier DE, et al. A beacon for dark times: palliative care support during the coronavirus pandemic. New Engl J Med Catalyst 2020; 1–9; Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0204. [Accessed 29 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakagawa S, Berlin A, Widera E, et al. Pandemic palliative care consultations spanning state and institutional borders. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020; 68:1683–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shalev D, Nakagawa S, Stroeh OM, et al. The creation of a psychiatry-palliative care liaison team: using psychiatry to extend palliative care delivery and access during the COVID-19 crisis. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020; 60:e12–e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE, et al. Enhanced support for shared decision-making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Heal Aff 2013; 32:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parsons JA, Johal HK. Best interests vs. resource allocation: could COVID-19 cloud decision-making for the cognitively impaired? J Med Ethics 2020; 46:447–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Opinions on consent, communication, and shared decision-making. American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-2.pdf. [Accessed 25 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-19-physicians-and-practitioners.pdf. [Accessed 25 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crisis Standards of Care: A toolkit for indicators and triggers. The national academics of sciences, engineering, and medicine. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18338/crisis-standards-of-care-a-toolkit-for-indicators-and-triggers. [Accessed 25 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mandel EI, Bernacki RE, Block SD. Serious illness conversations in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12:854–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.COVID Ready communication playbook. VitalTalk. Available at: https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/covid-19-communication-skills/. [Accessed 25 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ask-Tell-Ask. Coalition of Supportive Care for Kidney Patients and Pathways Project. Available at: https://gwu.app.box.com/s/g8sbwmgr60hjgyu5n48wkp0fd3zgp0l9. [Accessed 25 October 2020]

- 58.Lupu D, Anderson E, Moss A. Responding to hard questions and emotional distress about COVID-19 from dialysis patients or their families: maintaining balance in an unbalancing time. Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients. Available at: https://gwu.app.box.com/s/qof0kg83knuoorwv6r-x4iq6flr0rxc44. [Accessed 25 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Downloading your state’s advance directive. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Available at: https://www.nhpco.org/advancedirective/. [Accessed 25 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prepare Advance Directive. Prepare for your care. Available at: https://pre-prepareforyourcare.org/advance-directive-library. [Accessed 26 October 2020]

- 61.Adoption of national POLST form. National Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST). Available at: https://polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2020.10.19-National-POLST-Form-Adoption.pdf. [Accessed 24 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 62.My Way Project. George Washington University Nursing. Available at: https://nursing.gwu.edu/my-way-project. [Accessed 27 October 2020]

- 63.Life support during the COVID pandemic. Colorado Program for Patient-Centered Decisions. Available at: https://patientdecisionaid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/10.12.2020-COVID19-life-support-machine-V10-1.pdf. [Accessed 22 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patient crisis action plan. Conservative Kidney Management. Available at: https://www.ckmcare.com/Resources/Details/33. [Accessed 25 October 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ethical framework for healthcare institutions and guidelines for institutional ethics services responding to the coronavirus pandemic. The Hastings Center; 2020; Available at: https://www.thehastingscenter.org/ethicalframeworkcovid19/. [Accessed October 25, 2020] [Google Scholar]