Abstract

The striking imbalance between disease incidence and mortality among minorities across health conditions, including coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) highlights their under-inclusion in research. Here, we propose actions that can be adopted by the biomedical scientific community to address long-standing ethical and scientific barriers to equitable representation of diverse populations in research.

Keywords: health disparities, research representation, research inclusion, health inequities, community engagement

‘Who ought to receive the benefits of research and bear its burdens? This is a question of justice…’ - The Belmont Report

From 1932 to 1972, the US Public Health Service conducted the ‘Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the African American Male’, wherein study leaders convinced local physicians to withhold proven treatment for syphilis from 600 Black men without informed consent. By the end of the study, 128 Black men had lost their lives to syphilis and related complications and 59 spouses and children were infected. Imbued with, and enabled by, systemic racism, study leaders executed a carefully conceived, well-resourced recruitment and retention plan by employing sociologists, field workers, local Black institutions, and other trusted persons.

Nearly 50 years after the end of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, Black Americans are dying of COVID-19 at an age-adjusted rate 3.2 times that of white Americansi, yet comprise just 4% of participants in Moderna’s Phase I/II severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (Sars-CoV-2) vaccine triali, with improvements promised for Phase IIIii [1]. Similar trends exist for Latino and Indigenous Americans, with ~74 Latino deaths per 100 000 and 90 Indigenous deaths per 100 000i. Amid unprecedented urgency to accelerate the development of safe, effective SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, there is growing concern that trials will paradoxically fail to include those at greatest risk for contracting and dying from COVID-19 [2].

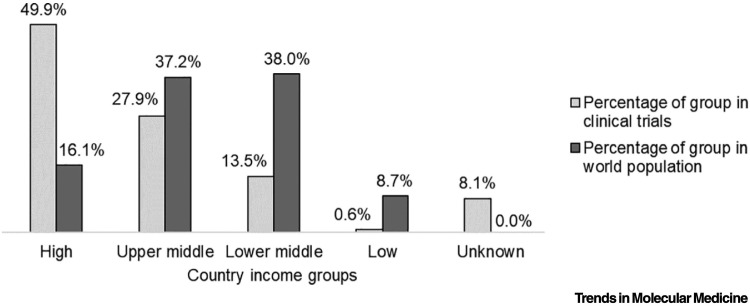

The time is long overdue to fulfill the Belmont Report’s principle of justice: equitable distribution of risks and benefits of researchiii. Despite good intentions, we propagate and maintain a system where non-white populations bear the burden of disease but do not reap the benefits of research advances. This phenomena is evident globally, whereby lower and middle income countries (LMICs), predominantly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, experience higher burdens of disease and lower life expectancy yet remain under-represented in clinical trials [3]. In 2019, there were 27 461 trials registered in high-income countries, which represent 16% of the world’s population, compared with 7743 trials in LMICs, which comprise the remaining 84% (Figure 1 )iv , v. Conversely, therapeutic breakthroughs made possible by trials conducted in LMICs may remain inaccessible to segments of these populations despite their disproportionate disease burden; for example, despite ethically controversial studies on preventative interventions for vertical transmission of HIV conducted during the 1990s in Africa, regional disparities in access to antiretroviral medications persistvi [4]. Shifting demographics, both globally and within the USA, demonstrate that such imbalances are likely to accelerate because non-white US populations are projected to become majority demographics by 2044vii.

Figure 1.

Clinical Trials and Population Density Globally by Country Income Groups in 2019.

The graph compares the share of total clinical trials with the share of the world population across high, upper-middle, lower-middle, low, and unknown country income groups. Lower- and middle-income countries are located predominantly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Clinical trial data were obtained from the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, whereas world population data was obtained from World Bank Open Data.

The exploitation and neglect of non-white populations in biomedical research are not insular phenomena but rather a direct consequence of dominant social forces and the histories that shape them. Effectively addressing inequities in research participation requires us to acknowledge their existence as harmful and unethical, as addressable rather than immutable. We must question the status quo, which imposes an undeserved expectation for non-white populations to trust in, and contribute to, research overseen by systems that have consistently proven themselves inadequate in protecting their safety and promoting their health [5]. Here, we offer crucial first steps to move biomedical research towards the ethical imperative of justice in research.

Strengthen Compliance, Reporting, and Transparency

Research participation inequities persist despite over 25 years of mandated inclusion and reporting policies from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the world’s largest public funder of biomedical research [6,7] (Box 1 ). Major research reports often omit or delay reporting demographics and outcomes by subpopulation [7], contravening NIH requirementsviii , ix. Similar omissions are observed globally and among studies not subject to NIH policies, such as a trial investigating the efficacy of dexamethasone in reducing mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19, which delayed reporting outcomes by race/ethnicity [8]. In a separate report evaluating hydroxychloroquine, all racial/ethnic minorities were grouped into a singular population [9], despite evidence indicating group-specific differences in outcomes across non-white demographicsi [10]. This illustrates the need for both improved engagement and inclusion, as well as broader adoption of transparent reporting and accountability structures, encompassing both appropriate detail and effective enforcement. Inequities often intersect, particularly across geographic and socioeconomic strata, yet measures of inclusivity often overlook socioeconomically disadvantaged or otherwise marginalized populations, such as disabled, unhoused, rural, older, institutionalized, hearing and vision impaired, justice system-involved persons, and sexual and gender minorities, each of which face distinct barriers to research accessibility. We must routinely measure and intervene upon intersecting, overlapping, and interacting dimensions of vulnerability to exclusion. Funding agencies, editors, reviewers, institutional review boards, and researchers all bear this responsibility.

Box 1. Reported Numbers for the Inclusion of Racial and Ethnic Minorities in NIH-Defined Extramural and Intramural Phase III Trials Reported for FY2018 Aggregated across All Institutes or Centers.

Table I reports aggregated racial and ethnic minority enrollment data for Phase III trials as reported by all NIH Institutes and Centers. The data sources for enrollment numbers in Table I are individual NIH institute and center reports available at https://report.nih.gov/recovery/inclusion_research.aspx. The following list outlines the exceptions or missing data not represented in Table I:

-

•

The Clinical Center (CC)/Intramural Research Program and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) only reported overall enrollment numbers by racial/ethnic group without gender distributions for NIH-defined Phase III clinical trials and, therefore, are not represented in Table I. Reported inclusion rates by group were: 2.3% American Indian/Alaska Native, 16.9% Asian, 10.4% Black, 0.0% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 35.9% white, 34.3% unknown or not reported, and 35.6% Hispanic for the CC/Intramural Research Program; and 5.7% American Indian/Alaska Native, 3.3% Asian, 16.8% Black, 0.6% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 64.9% white, 5.1% more than one race, 3.6% unknown or not reported, and 63.1% Hispanic for NIDDK.

-

•

The following institutes or centers did not support NIH-defined Phase III clinical trials for FY2018: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), and National Library of Medicine (NLM). National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) reported zero enrollment of participants in NIH-defined Phase III clinical trials for FY2018. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) reported supporting Phase III clinical trials in FY2018, but did not include the demographic breakdown for enrolled participants.

-

•

Enrollment reports include an ‘unknown’ group, which is not reflected in Table I, because the median percentage for participants designated as gender unknown across each racial and ethnic group is 0%.

Table I.

Aggregated Inclusion Rates for Racial and Ethnic Minorities in NIH-Defined Extramural and Intramural Phase III Trials Reported for FY2018

| Racial or ethnic minority | Female |

Male |

|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | Median (range) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.1% (0.0–0.4%) | 0.2% (0.0–0.7%) |

| Asiana | 1.0% (0.0–5.8%) | 1.3% (0.0–8.0%) |

| Black or African Americanb | 11.9% (4.2–49.8%) | 8.8% (3.7–27.8%) |

| Hispanic | 4.2% (0.0–30.6%) | 4.8% (0.0–22.4%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.1% (0.0–1.1%) | 0.0% (0.0–1.5%) |

| White | 29.1% (2.4–57.0%) | 27.1% (5.3–62.4%) |

| More than one race | 1.3% (0.1–9.5%) | 0.9% (0.0–6.8%) |

| Unknown or not reported | 1.6% (0.0–18.4%) | 1.3% (0.0–25.8%) |

Fogarty International Center (FIC) reported one Phase III clinical trial for FY2018 with a 100% Asian enrollment rate, which is not included in the calculation for the medians and ranges in the table.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) reported high enrollment rates for Black/African American (AA) participants, at 49.8% Black/AA female, 22.3% Black/AA male, 0.7% Black/AA unknown; and 37.0% Black/AA female, 27.8% Black/AA male, and 0.0% Black/AA unknown, respectively. Excluding these two agencies, the range for Black/AA enrollment is 4.2–23.1% for females, 3.7–20.0% for males, and 0.0–16.8% unknown.

Alt-text: Box 1

Promoting accountability necessitates a shift away from assuming prospective participants as distrustful to assuming researchers and institutions must demonstrate trustworthiness. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study in particular is frequently invoked to rationalize under-enrollment of non-white populations, perpetuating a harmful narrative that blames non-white populations for their under-representation [11]. Less often discussed is the fact that human subject violations continue to occur, such as over-representation of Black Americans in trials that do not require informed consent [12], and a recent large-scale malaria vaccine trial conducted across Africa that failed to obtain informed consent from parents of children who received the experimental vaccine [13]. Beyond these failings, the rhetoric of research participation itself, such as ‘recruiting’, ‘retaining’, and ‘hard to reach’, further objectifies non-white populations, many of whom have a long history of being pursued, retained, and reached at their peril.

Identify, Measure, and Systemically Address Exclusionary Research Practices

Just, rigorous research compels optimal participation from all without undue burden or exclusion. Indeed, many routinely applied statistical tests do not account for any selection bias due to recruitment factors. Yet, participation inequities are often normalized despite being scientifically immaterial, such as requiring English-language proficiency or health insurance. Exclusion criteria based on ever-growing lists of comorbidities may be designed out of an abundance of caution but disproportionately impact under-represented groupsx. Returns of value for participants and communities are rarely considered, including provisions for emergent health needs, compensation, or reimbursement. Assumptions of flexible schedules and easy access to research spaces exacerbate inaccessibility. Clinicians may suffer from inexperience or bias, driving inappropriate diagnosis and failing to refer under-represented patients to research. These practices, designed for the convenience of the researcher, favor privileged populations, demonstrating that social determinants of health unnecessarily and unjustly serve as determinants of research participation.

Invest in Sustained, Reciprocal Relationships with Marginalized Communities

Research is appropriately understood as a form of relationship among researchers, institutions, participants, and their communities. However, researchers and institutional stakeholders typically unilaterally define research goals, questions, participation requirements, and offered benefits, if any. Unlike clinician–patient relationships, there are no standard mechanisms for research participants to offer feedback on their experience. Research relationships must become balanced, reciprocal, and community informed, without centering researcher and institutional priorities. When sustained over time, reciprocal relationships will foster the trust and empowerment needed to rapidly engage time-sensitive research endeavors, such as those imposed by COVID-19.

Beyond Proportional Representation

Proportional representation, or inclusion that parallels population demographics, is frequently referenced as an accepted definitional standard for inclusivity but is not a scientifically derived threshold for success. Proportional representation is often unable to detect meaningful differences across and within subpopulations, which represent heterogeneous cultures, languages, and histories, often violating statistical assumptions of homogeneity between groups [14]. Infectious disease outbreaks, such as COVID-19, where infections do not parallel population demographics, demonstrate the inadequacy of relying on proportional representation as a common rule. Scientific advancements capable of reducing health inequities compel moving beyond proportional representation and comparisons, which often center white populations as a referent group, toward mechanistically informed designs and frameworks that enable robust assessment of differential patterning of underlying exposures that contribute to disparate health outcomes.

Develop Empirically Derived, Applied Sciences of Research Participation and Inclusion

Scientists need evidence-based guidance to reliably inform decisions for individual study design, resource allocation, engagement, and meaningful community involvement. Long-term solutions must move beyond one-off recruitment and retention plans toward an ontologically quantified science of inclusion as a scientifically rigorous, necessary process. Anecdotal understandings of research participation are as inadequate in mitigating research participation barriers as anecdotes are in informing any other scientific process. This evidence base is also needed to guide interventions targeting participation barriers at individual and structural levels.

Concluding Remarks

The alarming imbalance between the high incidence, morbidity, and mortality among minority communities from COVID-19 and other diseases, and their limited access to research and investigative COVID-19 therapeutics, illustrates a complicated intersection of overlapping and overlooked crises: inequitable under-representation in research and the lack of readily available interventions or infrastructure to strengthen inclusion and ameliorate long-standing mistrust with health care and biomedical research. Unaddressed, research injustices will continue to translate into downstream disparities in the efficacy, safety, and accessibility of treatments and interventions developed with, and, thus, for, predominantly white, privileged populations for conditions that disproportionately impact minorities, as observed across many health conditionsxi , xii [15]. We can and must address these crises to respond to all principles of the Belmont Report and finally, urgently, deliver on the promised principle of justice, by creating a research enterprise that is accessible and equitable for all.

Acknowledgments

These authors acknowledge funding by the National Institutes of Health [K76AG060005 (A.G-B.)], [DP1AG069873 (J.D.J.)], [U54MD010722 (C.H.W.)], and [UL1TR000445 (C.H.W.)]. Dr. J.D.J. also receives funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation under grant number 18881. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Michael J. Fox Foundation.

Resources

iwww.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-raceiiwww.cnbc.com/2020/09/04/moderna-slows-coronavirus-vaccine-trial-t-to-ensure minority-representation-ceo-says.htmliiiwww.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/the-belmont-report-508c_FINAL.pdfivhttps://data.worldbank.org/?locations=XP-XN-XT-XDvwww.who.int/research-observatory/monitoring/processes/clinical_trials_1/en/viwww.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2923_SFSFAF_2017progressreport_en.pdfviiwww.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdfviiihttps://orwh.od.nih.gov/sites/orwh/files/docs/ORWH_BR_MAIN_final_508.pdfixhttps://orwh.od.nih.gov/sites/orwh/files/docs/NIH-Revitalization-Act-1993.pdfxwww.fda.gov/media/134754/downloadxiwww.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2018-10/alzheimers-disease-recruitment-strategy-final.pdfxiiwww.aafa.org/media/2743/asthma-disparities-in-america-burden-on-racial-ethnic-minorities.pdfReferences

- 1.Jackson L.A., et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1920–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borno H.T., et al. COVID-19 disparities: an urgent call for race reporting and representation in clinical research. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2020;19:100630. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2020.100630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weigmann K. The ethics of global clinical trials. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:566–570. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lurie P., Wolfe S.M. Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;337:853–856. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709183371212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scharff D.P., et al. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viergever R.F., Hendriks T.C. The 10 largest public and philanthropic funders of health research in the world: what they fund and how they distribute their funds. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2016;14:12. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0074-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geller S.E., et al. The more things change, the more they stay the same: a study to evaluate compliance with inclusion and assessment of women and minorities in randomized controlled trials. Acad. Med. 2018;93:630–635. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.RECOVERY Collaborative Group et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 - preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. Published online July 17, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.RECOVERY Collaborative Group et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022926. Published online October 8, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lassale C., et al. Ethnic disparities in hospitalisation for COVID-19 in England: the role of socioeconomic factors, mental health, and inflammatory and pro-inflammatory factors in a community-based cohort study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;8:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd R.W., et al. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Aff. 2020 doi: 10.1377/hblog20200630.939347. Published online July 2, 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman W.B., et al. A systematic review of the food and drug administration's 'exception from informed consent' pathway. Health Aff. 2018;37:1605–1614. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doshi P. WHO’s malaria vaccine study represents a ‘serious breach of international ethical standards’. BMJ. 2020;368:m734. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitfield K.E., et al. Are comparisons the answer to understanding behavioral aspects of aging in racial and ethnic groups? J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2008;63:P301–P308. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.5.P301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zavala V.A., et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br. J. Cancer. 2021;124:315–332. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]