Abstract

Research has shown that Native Hawaiians disproportionately suffer from behavioral disorders and chronic physical diseases, yet they have historically lacked effective and culturally relevant prevention interventions to address their pervasive health disparities. This article systematically reviewed the recent culturally relevant prevention intervention literature focused on Native Hawaiians. In this review, we assessed 14 peer-reviewed articles published between 2015 and 2020 that met inclusion and exclusion criteria pertaining to the development and/or evaluation of prevention interventions for Native Hawaiians. The reviewed studies evaluated 10 different interventions that were developed using deep-structure adaptation or culturally grounded procedures, and primarily focused on prevention of substance use, obesity/diabetes, and pregnancy/sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Compared with prior, related literature reviews, the present review suggests an overall advancement in prevention science for Native Hawaiians, evidenced by an increase in federal funding and randomized controlled clinical trials of prevention interventions for the population. This review provides an update to the state of the science for Native Hawaiian prevention interventions, and points to areas of future research and development.

Keywords: Native Hawaiian, prevention, intervention, health disparities, health promotion

Epidemiological health research has indicated that Native Hawaiians have disproportionately suffered from physical and mental health conditions, such as obesity [1], diabetes [2, 3], chronic kidney disease [4], suicidal behaviors [5, 6], and substance abuse [6–8]. However, research has historically lagged, in terms of developing effective, culturally relevant interventions to address pervasive health disparities of Native Hawaiians [9, 10]. The lack of empirically supported interventions in the scientific literature for Native Hawaiians has been recently addressed through specific requests for research proposals from the National Institutes of Health, such as administrative supplements focused on the inclusion of Native Hawaiians in minority health and health disparities research issued by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NOT-MD-19–023), and the RFA entitled “Intervention Research to Improve Native American Health” or IRINAH [11]. While the latter call for proposals broadly focused on Indigenous U.S. populations, only one of the 35 funded IRINAH projects to date is focused on Native Hawaiians. The dearth of Hawaiian-focused IRINAH projects may indicate that this funding opportunity, and similar large-scale efforts, may not be effective in increasing the amount of intervention research for this population.

In order to examine the impact of broader systemic efforts to expand and develop the intervention literature for Native Hawaiians, the present study systematically examines the culturally relevant prevention intervention literature focused on this population. Specifically, we identified and synthesized recent empirical studies of Hawaiian-focused prevention interventions that were developed using either deep-structure adaptations or culturally grounded methods [12]. Key emergent themes were compared and contrasted across studies, and areas for future prevention research for Native Hawaiians are discussed.

Literature Review

Native Hawaiians: A Brief Background

For this literature review, “Native Hawaiians” are defined as descendants of the original inhabitants of the Pacific Region of Polynesia (e.g., Hawaiʻi, Tonga, and Sāmoa). This population is distinct from the broader contextualized definitions of Hawaiians, which include citizens or residents of Hawaiʻi who are long-term residents or were born on the islands [13]. Numbering over a half-million in the most recent U.S. Census, they reside primarily within the State of Hawaiʻi and in the Western states of the Continental U.S. [14]. Similar to other Indigenous populations, Native Hawaiians have historically experienced colonization, with accompanying adverse effects. Specifically, Native Hawaiians came under U.S. occupation in 1893, when Queen Liliʻuokalani, the sovereign of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, was illegally deposed. Descendants of early missionaries in Hawaiʻi, who became wealthy businessmen and landowners, conspired to overthrow the Hawaiian monarchy [15]. This event was a primary source of significant cultural and political trauma for Hawaiians, impacting them spiritually, physically, economically, socio-politically, and psychologically [16]. The United States eventually annexed Hawaiʻi in 1898, and granted it statehood in 1959. However, by this time, significant adverse population effects were well underway. In terms of population health, early Western settlers in the 1800s brought an influx of diseases to the islands, including tuberculosis, measles, influenza, and syphilis, resulting in a 90 percent decrease of the Native Hawaiian population a century after the settlers’ arrival [13, 17].

As a part of the post-colonial experience, Native Hawaiians have had to balance a transnational identity, navigating social networks and linkages between two communities with distinct worldviews [18]. Specifically, many Native Hawaiians experience stress in balancing conflicting Indigenous and Western norms within their homeland, which is an outgrowth of past colonization [17]. The emotional and physical stress of navigating conflicting, dual cultures can hinder the psychosocial adaptation of Native Hawaiians [19]. For example, the norms of interdependence and collectivism in Hawaiian culture conflict with individualism in Western culture. Collectivism in Hawaiian culture is particularly evident in the interpersonal influence of immediate, extended, and ascribed families within the context of Native Hawaiian communities [18, 20]. The familial relational context within Hawaiian communities profoundly impacts individuals’ social and behavioral norms, values, and worldviews, and intensifies both psychosocial risk of and protection against adverse health consequences [20]. For example, in the area of substance use, Goebert et al. [21] found that family emotional support functioned as a protective factor against Native Hawaiian youths’ substance use in a large (N = 4000) epidemiological study. Conversely, Okamoto et al. [7] found that offers to use drugs from family members were a risk factor for Native Hawaiian youths’ substance use, significantly predicting their use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana in their study. These studies not only highlight the salience of family-based risk and protection for Native Hawaiians, but they also point to the need for culturally relevant substance use prevention programs and services to ameliorate Native Hawaiian health disparities.

Native Hawaiians and Prevention Interventions

To date, there have been two systematic literature reviews that have partially captured the nature and extent of prevention interventions for Native Hawaiians. Edwards et al. [10] examined the empirical literature from 1995 to 2009 focused on Native Hawaiian youth and drug use. They identified 32 articles focused on this topic, with the majority of them characterized as epidemiological studies. Only 4 of the articles in their review (13%) focused on empirical evaluations of programs. This subset of studies was comprised of evaluations of grassroots, community-based programs for Hawaiian youth, and as a result, lacked studies that used clinical trial procedures to establish program efficacy. The Edwards et al. study reflected the state of the science for Native Hawaiians and prevention in its early stage of development. The studies included in the review established community-based need for prevention through examining epidemiological rates, and examined community driven, grassroots efforts to combat a pervasive health disparity issue (substance misuse).

Lauricella, Valdez, Okamoto, Helm, and Zaremba [22] conducted a systematic review of empirical literature from 2003–2014 focused on culturally grounded prevention interventions for minority youth populations. They identified 31 empirical articles focused on this topic, with 4 articles (14%) focused on the early-stage development of a culturally grounded, school-based, drug prevention curriculum for rural Native Hawaiian youth (Hoʻouna Pono). The Hoʻouna Pono studies used a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods to develop curriculum content on skills and strategies to resist drugs in difficult social situations with peers and family members. While the Lauricella et al. study was able to identify the emergence of empirically supported, culturally relevant prevention interventions for Native Hawaiians in the scientific literature, none of the Hawaiian-focused studies described in their review were at the phase to employ clinical trial procedures. Thus, while progress appeared to be emerging in the development of prevention interventions for Native Hawaiians since the Edwards et al. [10] study, the state of the science still appeared to reflect a relatively early stage of prevention intervention development for this population.

More recently, specific efforts to develop prevention interventions for Native Hawaiians have been described in the literature. For example, Kaholokula, Ing, Look, Delafield, and Sinclair [23] described the process of developing two culturally focused interventions—KāHOLO and PILI ‘Ohana—that target obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease prevention. PILI ‘Ohana was created through a deep-structure adaptation of an evidence-based intervention (the Diabetes Prevention Program - Lifestyle Intervention) using community-based participatory research principles and practices. KāHOLO used culturally grounded methods to develop a cardiovascular disease prevention program that focused on the traditional cultural dance of Hawaiʻi (hula). These programs highlight the recent growth in the state of Native Hawaiian prevention science, and indicate the future direction of prevention science with the population.

Relevance of the Study

In order to examine the impact of recent Federal efforts to increase intervention research focused on Native Hawaiians, this study systematically examined the recent prevention intervention literature focused on the population. The present review also serves as an update to the prior systematic literature reviews [10, 22], which both suggested early stages of development for the prevention intervention literature for Native Hawaiians. Unlike the prior literature reviews, which focused on interventions for children and adolescents, the present review encompasses prevention literature for Native Hawaiians across the life span. This review also includes deep-structure cultural adaptations to interventions, as well as culturally grounded approaches, in order to address the prevention needs of Hawaiian communities dealing with a wide array of pervasive health disparities. The findings from this literature review have implications for the health promotion of Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and other Indigenous populations, especially those across the Pacific region.

Method

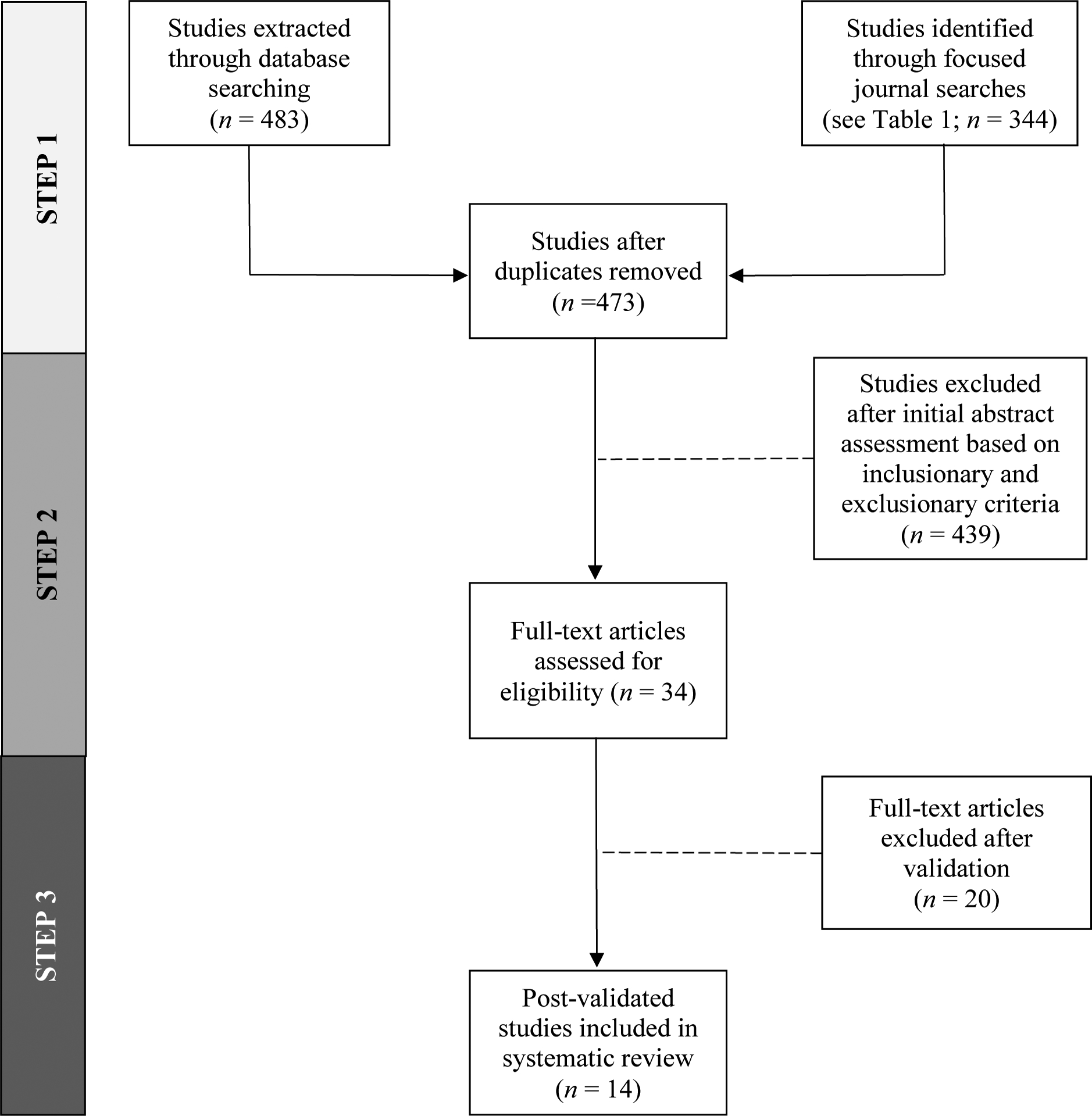

Figure 1 illustrates a PRISMA flow diagram of the process of identifying articles for this review. In Step 1, the three primary authors conducted a computerized search of online databases, including PsycNET, PubMed, and EBSCO. To ensure mutual exclusivity with the Edwards et al. [10] and Lauricella et al. [22] literature reviews and to highlight the most recent empirical research, we focused on studies published between 2015 and 2020. In each database, the primary terms “health”, “Native Hawaiian”, and “prevention” were used. During these searches, we employed other relevant terms, such as “intervention”, “culturally grounded”, and “culturally relevant” to expand the search perimeter. The online database search yielded 483 different articles. We also conducted a focused search of 13 different journals that have a history of publishing research focused on Native Hawaiians (see Table 1). The focused journal search yielded 344 articles. After eliminating duplicate articles between the two search methods, there were 473 unique articles for potential inclusion in this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for Literature Review. This figure illustrates our process for identifying and reducing the number of articles included this review, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.

Table 1.

Focused Journal Searches: Empirical Prevention Articles on Native Hawaiians: 2015–2020*

| Journal | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| American Journal of Community Psychology | 40 |

| Children & Schools | 3 |

| Health & Social Work | 10 |

| Health Education & Behavior | 31 |

| Health Promotion Practice | 33 |

| Journal of Community Psychology | 55 |

| Journal of Health Care for the Poor & Underserved | 25 |

| Journal of Primary Prevention | 13 |

| Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities | 66 |

| Prevention Science | 41 |

| Progress in Community Health Partnerships | 9 |

| Social Work | 6 |

| Social Work Research | 12 |

| Total | 344 |

Search Term: Hawaiian

In Step 2, the three primary authors read and evaluated all abstracts based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study. Articles were included in this study if they (1) focused on Native Hawaiians, either exclusively or in combination with related populations (e.g., Pacific Islanders, other Indigenous groups); (2) focused on the development and/or evaluation of culturally adapted1 or culturally grounded programs; (3) described an empirically driven approach to the development and/or evaluation of the programs; and (4) were published between 2015 and 2020. Articles were excluded in this study if they (1) focused on populations other than Native Hawaiians. These included articles that may have sampled Native Hawaiians, but the focus was on the broader ethnic categorization (e.g., Asian/Pacific Islanders); (2) focused on culturally generic or surface-structure adaptations of interventions; (3) were non-empirical in nature (e.g., descriptive or theoretical articles); (4) were not peer reviewed; and (5) were published prior to 2015. Based on our initial assessment of articles, we reduced the number of articles to 34.

In Step 3, the research team screened the full text of the 34 remaining articles using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. During this step, the full-text analysis of articles revealed that several of them were primarily etiological or correlational in nature, or described research initiatives, such as community/university collaborations, rather than prevention programs for Native Hawaiians. These articles were eliminated from inclusion in the study. One particular article was a protocol paper that described a prospective randomized controlled trial of the KāHOLO program [24]. Because this paper did not report on outcome findings from the program, we deemed it non-empirical in nature and eliminated it from the pool of articles. The full text analysis of articles in Step 3 reduced the number of articles to 14.

Results

The 14 peer-reviewed articles which met inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study are outlined in Table 2. The majority of studies in this review focused on substance use prevention (33%), followed by obesity/diabetes (20%) and pregnancy/STI (20%) prevention. The development and/or evaluation of 10 different prevention interventions were described across the reviewed articles. All but one study (Patel et al. [25]) took place exclusively in the State of Hawaiʻi. Of the Hawaiʻi-based studies, 31% took place on multiple islands across the State, 31% took place on the Island of Oʻahu, 31% took place on Hawaiʻi Island, and 7% (1 article) did not disclose its study’s location.

Table 2.

Results from Literature Review

| Study | Program Name | Issue | N Size | Study Type | Age Range | Clinical/ Translational Level | Study Design | Major Finding(s) | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abe et al. [33] | Pono Choices | Pregnancy and STIs | 2,203 | CG | Pre-Adolescent | T2 | RCT | Significant increases in sexual health knowledge; non-significant changes in risky sexual behaviors, attitudes, skills, or intentions 12-months after baseline | OAH |

| Cassel et al. [29] | SunSafe Adaptation | Skin Cancer | 50 (Focus Groups); 250 (Surveys) | DSA | Adolescent | T2 | MIX | Significant increase in knowledge, attitudes and sun protection behaviors, from pre- to post-test | CDC |

| Helm et al. [34] | Puni Ke Ola Photovoice Project | Substance Use | 10 | CG | Adolescent | Tl | QUAL | An emerging framework for a community-based, Native Hawaiian model of drug prevention | NIMHD, SCRA, Queens |

| Ing, Miyamoto, etal. [35] | PILI@Work | Obesity | 217 | DSA | Adult | T2 | RCT | Significant improvements in weight loss and systolic and diastolic blood pressure from baseline to 3-month post-intervention | NCI, NIMHD, Queens |

| Ing, Zhang, et al. [36] | Partners in Care Adaptation | Type 2 Diabetes | 47 | DSA | Adult | T2 | RCT | Significant improvements in HbAlc, diabetes-related self-management knowledge, and behaviors from baseline to 3-month assessment | NIMHD, Queens |

| Ing et al. [37] | PILI@Work | Obesity | 217 | DSA | Adult | T2 | RCT | Participants receiving a face-to-face intervention internalized their locus of weight control and perceived more family support for weight loss from 3-month to 12-month follow up | NCI, NIMHD, Queens |

| Kaholokula et al. [26] | Ola Hou i ka Hula | Hypertension | 55 | CG | Adult | T2 | RCT | Significant reduction in systolic blood pressure in intervention group, compared to control group | NIMHD, NIGMS, Queens |

| Kaʻopua et al. [38] | N/A | HIV and Anal Cancer | 28 | DSA | Adult | Tl | QUAL | Identified risk and reluctance to anal cancer screening, and strategies for destigmatizing anal cancer | NIMHD |

| Okamoto et al. [39] | Hoʻouna Pono | Substance Use | 213 | CG | Pre-Adolescent | T2 | RCT | Significant increases in non-confrontational drug resistance strategies in intervention group; significant increases in fighting in control group | NIDA |

| Okamoto et al. [40] | Hoʻouna Pono | Substance Use | 8 | CG | Adult | Tl | QUAL | Stakeholders validated the cultural validity and educational utility of the curriculum | NIDA |

| Okamoto et al. [41] | Hoʻouna Pono | Substance Use | 486 | CG | Pre-Adolescent | T2 | RCT | Small, significant changes in the intended direction for cigarette/e-cigarette and hard drug use | NIDA |

| Okamoto et al. [30] | Hoʻouna Pono | Substance Use | 24 | CG | Adult | T3 | QUAL | Implementation strategies included cultural validation of the curriculum, and creating flexibility in the curriculum for diverse educational settings | NIDA |

| Patel et al. [25] | STRIVE Project |

Health Disparities | 1.4 mil | DSA | Adult | T2 | MIX | Described culturally adapted, community-based approaches to increase healthy food intake and physical activity | CDC,NIMHD |

| Takishima-Lacasa and Kameoka [27] | Girl Power Hawaiʻi | STI | 13 | DSA | Adolescent | Tl | QUAL | Described deep-structure cultural and content validation of the adapted curriculum using a phased model | N/A |

NOTE. Issue: STI = Sexually Transmitted Infection, HIV = Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Study Type: CG = Culturally Grounded; DSA = Deep Structure Adaptation. Clinical/Translational Level: T1 = Program Development; T2 = Efficacy/Effectiveness Trials; T3 = Implementation and Dissemination. Study Design: MIX = Mixed Methods; RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; QUAL = Qualitative. Funding: CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; OAH = Office of Adolescent Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health; NIDA = National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health; NCI = National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; NIGMS = National Institute on General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health; SCRA = Society of Community Research and Action; Queens = Queen’s Health Systems.

Half of the studies used culturally grounded methodologies to develop programs or curricula. These methods entailed processes or procedures to develop interventions from the values, beliefs, and worldviews of Native Hawaiian communities. For example, Kaholokula et al. [26] described the social, educational, and cultural components of Ola Hou i ka Hula. A precursor to the KāHOLO program, Ola Hou i ka Hula integrated the traditional dance of Native Hawaiians (hula) as an integral physical activity component of a community-based hypertension prevention program. Researchers employing deep-structure adaptations of evidence-based curricula typically utilized focus groups to meaningfully infuse cultural content and context into their interventions. Takishima-Lacasa and Kameoka [27], for example, described a phased model for their deep-structure adaptation of Girl Power, which included the selection of an evidence-based intervention from the scientific literature, development of an adaptation guide in collaboration with community stakeholders based on the selected intervention, and focus groups with NHPI girls to inform the adaptation of intervention content.

Fishbein, Ridenour, Stahl, and Sussman [28] described a translational spectrum of prevention science, which classifies studies as T0 (basic discoveries), T1 (program development), T2 (efficacy/effectiveness trials), and T3 (implementation and dissemination). Approximately a third of the studies (29%) in this review were classified as T1 studies. They described qualitative methods used to adapt and/or validate prevention programs for Native Hawaiians, thus reflecting the early stages of culturally relevant program development. Nearly two-thirds of the studies in this review (64%) were classified as T2 studies. The majority of T2 studies in this review (78%) used randomized controlled trial designs to evaluate program efficacy and/or effectiveness. Most of these studies reported relatively small sample sizes and/or modest positive program effects. Two T2 studies used a combination of both qualitative and quantitative methods to evaluate program effects. For example, Cassel et al. [29] described their use of focus groups to adapt the SunSafe skin cancer prevention curriculum for NHPI youth, and described the evaluation of their adapted curriculum using randomized controlled trial procedures. Finally, one study in this review was classified as a T3 study. This study focused on the program implementation of a culturally grounded, substance use prevention curriculum for Native Hawaiian youth [30].

Notably, 93% of the studies in this review received some form of federal funding to support the development and/or evaluation of a culturally relevant program for Native Hawaiians. The most commonly cited federal funding source was the National Institutes of Health (NIH; 79%). Within NIH, the most commonly cited institutes funding studies in this review were the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (41%), followed by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (23%). Almost half of the studies (46%) received funding from multiple sources (i.e., federal- and state-level funding sources).

Discussion

This study systematically examined the recent empirical prevention literature focused on Native Hawaiians. Despite its compressed time frame (2015–2020), this review identified 14 articles meeting relatively restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria. This is contrasted with only four intervention articles focused on Native Hawaiian youth and drug use over a 15-year time span (1995–2004) identified by Edwards et al. [10], and four Hawaiian-focused prevention articles over a 12-year time span (2003–2014) identified by Lauricella et al. [22]. While Edwards et al. and Lauricella et al. were more limited in their scope compared to the present study, comparing those findings to the present findings suggest that there has been more intervention research for Native Hawaiians that has been generated in recent years.

In terms of the types of studies, the present review also demonstrates an increase in the number of efficacy and effectiveness trials focused on Native Hawaiians, compared to prior systematic reviews. Specifically, Edwards et al. [10] found that the majority of studies focused on Native Hawaiian youth in their review were epidemiological in nature, suggesting that prevention science for Native Hawaiians was primarily within the T0 (basic discovery) phase in the late 1900s and early 2000s. Further, Edwards et al. indicated that the few intervention studies included in their review were predominantly community grassroots programs that added an a posteriori evaluation component. This is contrasted to the planned, purposeful, T2 clinical trials that were identified and included in the present literature review. The present review even included a recent T3 study on prevention implementation science for Native Hawaiians. Overall, these findings suggest that the state of the science of Native Hawaiian prevention research has been advancing through the translational spectrum of prevention science described by Fishbein et al. [28] over the past decade.

The majority of the studies included in this review were supported by federal funding, and several of them were supported by multiple federal sources (e.g., NIMHD, NIGMS, and NIDA). The majority of the calls for research proposals from these federal sources are topical in nature (e.g., suicide, substance use, prevention), and those that are population based, such as IRINAH [11], have been more broadly focused on Indigenous groups in general, including American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians. This demonstrates that most of the studies in this review were funded by federal mechanisms that did not specifically target the Native Hawaiian population. The number of extramurally funded prevention studies focused on Native Hawaiians in this review is in stark contrast with anecdotal and empirical accounts from 10 years ago that indicated a scientific bias against research focused on the population [31, 32]. Okamoto [31], for example, described common critiques against research focused on Native Hawaiians. Studies with the population were described as “non-generalizable” or “limited” in their reach, suggesting they had a low scientific impact because they did not serve to inform the larger ethnic rubric (i.e., Asian/Pacific Islanders). We would argue that the emerging prevalence of funded prevention studies in recent years focused on Native Hawaiians represents a paradigmatic shift over the past decade. It suggests that the scientific community increasingly recognizes the importance of culturally relevant prevention research for Native Hawaiians, and the implications of this research for Indigenous and Pacific Islander health.

Recent advances in Native Hawaiian prevention science can largely be attributed to the earlier contributions of Native Hawaiian researchers, such as Marjorie Mau and Keawe Kaholokula, who have advocated over the years to fund more research focused on Native Hawaiian health from federal funding agencies and to recognize Native Hawaiians as Indigenous people. However, despite these scientific advances, this review points to areas of future prevention research that are needed for Native Hawaiians. While studies in this review addressed health disparity issues relevant to Native Hawaiians (e.g., youth substance misuse, obesity, diabetes, and STIs), there were a lack of culturally relevant prevention studies related to mental health (e.g., suicidality), and some chronic physical conditions (e.g., kidney disease). Further, the majority of the studies in this review took place in the State of Hawaiʻi. As a result, much is still not known about the prevention intervention needs of Native Hawaiians living in the Continental U.S., where nearly 50% of all Native Hawaiians reside. Future research should address these gaps in the science.

Finally, it is worth noting that, of the 14 studies included in this review, only two were written by self-identified Native Hawaiian researchers as lead authors. This highlights the fact that the scientific workforce lacks Native Hawaiian prevention researchers to contribute to culturally relevant prevention development and evaluation [15]. Future federal efforts should work toward advancing both Native Hawaiian prevention science and the Native Hawaiian scientific workforce, in order to address the specific needs of Hawaiian communities and to continue to move the field forward.

Limitations of the Study

There were several limitations to this study. First, this review focused on a narrow (5 year) time period. This decision was made to avoid overlap with related systematic literature reviews [10, 22], thereby reducing redundancies in the included studies with prior reviews, as well as focusing the review on the most up-to-date published prevention research on Native Hawaiians. However, this decision left out several adult-focused prevention studies published prior to 2015 in our review. Second, because this review focused on the published, peer-reviewed literature, culturally relevant prevention programs for Native Hawaiians that were in the early (pre-publication) stages of development or were unpublished were not included in this review. Future literature reviews could incorporate the “grey” literature to identify unpublished interventions for Native Hawaiians, although these types of articles are often difficult to find.

Conclusions

Despite its limitations, this study identified recent advances in the prevention intervention literature focused on Native Hawaiians. The findings suggest that recent federal efforts to expand and develop prevention interventions for Native Hawaiians have resulted in advancing the translational spectrum of prevention science for the population. Although progress has been made, there still exists an overall lack of research in the recent prevention literature focused on Native Hawaiians. As a result, there are several health disparity areas for the population that need future research. More T3 studies focused on the dissemination and implementation of efficacious prevention programs for Native Hawaiians need to be conducted. This could be achieved through federal investments in funding opportunities intended to move the translational spectrum of prevention science for Native Hawaiians into the realm of T3 studies, and a focused effort in training new and/or early-stage investigators in conducting T3 studies with Native Hawaiian communities. Finally, more studies are needed that are led by an expanded cadre of Native Hawaiian prevention researchers. Future related systematic literature reviews might focus on culturally relevant prevention interventions for other Pacific Islanders, such as Samoans, Tongans, and Marshallese, in order to establish the need for research with these related, yet distinct, populations. These groups collectively comprise the majority of the Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander categorization, yet have received less federal health research funding than Native Hawaiians. By continuing to advance the field of prevention for Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders, pervasive health disparities will be addressed and alleviated for these populations.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse.

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA037836, R01 DA037836-04S1, R34 DA046735, and R34 DA046735-02S1). The authors do not claim any conflicts of interests or competing interests in the publication of this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests/Competing Interests

The authors do not claim any conflicts of interests or competing interests in the publication of this study.

Ethics Approval

Not Applicable

Consent to Participate

Not Applicable

Consent for Publication

Not Applicable

Availability of Data and Material

This study identified and synthesized published and/or publicly available scientific literature.

Code Availability

Not Applicable

For cultural adaptations, the programs were required to use deep-structure adaptations, which entailed processes or procedures to infuse cultural values, beliefs, worldviews, and behaviors into an intervention. These approaches were opposed to surface-structure adaptations, which entailed minor changes to an intervention through replacing universal concepts with their cultural equivalents, such as “family” to “‘ohana”. See Okamoto et al. [12] for details.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies that were included in this literature review.

- 1.Bacog AM, Holub C, Porotesano L. Comparing obesity-related health disparities among Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, Asians, and Whites in California: Reinforcing the need for data disaggregation and operationalization. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2016;75(11):337–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grandinetti A, Kaholokula JK, Theriault AG, Mor JM, Chang HK, Waslien C. Prevalence of diabetes and glucose intolerance in an ethnically diverse rural community of Hawaiʻi. Ethn Disease. 2007;17(2):250–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aluli NE, Jones KL, Reyes PW, Brady SK, Tsark JU, Howard BV. Diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors in Native Hawaiians. Hawaii Med J. 2009;68(7):152–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mau MK, West MR, Shara NM, Efird JT, Alimineti K, Saito E, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical factors associated with chronic kidney disease among Asian Americans and Native Hawaiians. Ethn Health. 2007;12(2):111–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Else IRN, Andrade NN, Nahulu LB. Suicide and suicidal-related behaviors among indigenous Pacific Islanders in the United States. Death Stud. 2007;31(5):479–501. doi: 10.1080/07481180701244595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subica AM, Wu L-T. Substance use and suicide in Pacific Islander, American Indian, and multiracial youth. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6):795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Edwards C, Giroux D. The social contexts of drug offers and their relationship to drug use of rural Hawaiian youths. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2014;23(4):242–52. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2013.786937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong MM, Klingle RS, Price RK. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among Asian American and Pacific Islander Adolescents in California and Hawaii. Addict Behav. 2004;29(1):127–41. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(03)00079-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamoto SK. Current and future directions in social work research with Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. J Ethnic Cultur Divers Soc Work. 2011;20(2):93–7. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2011.569979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards C, Giroux D, Okamoto SK. A review of the literature on Native Hawaiian youth and drug use: Implications for research and practice. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2010;9(3):153–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Intervention Research to Improve Native American Health (IRINAH): National Institutes of Health; 2020. [Available from: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/nativeamericanintervention/.

- 12.Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Holleran Steiker LK, Dustman PA. A continuum of approaches toward developing culturally focused prevention interventions: From adaptation to grounding. J Prim Prev. 2014;35(2):103–12. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0334-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCubbin LD, Marsella A. Native Hawaiians and psychology: The cultural and historical context of indigenous ways of knowing. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2009;15(4):374–87. doi: 10.1037/a0016774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hixson L, Hepler BB, Kim MO. The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander population: 2010. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. p. 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaholokula JK, Okamoto SK, Yee BWK. Special issue introduction: Advancing Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander Health. Asian Am J Psychol. 2019;10(3):197–205. doi: 10.1037/aap0000167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams IL, Laenui P, Makini GK, Rezentes WC. Native Hawaiian culturally based treatment: Considerations and clarifications [published online ahead of print, 2020]. J Ethn Subst Abuse. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2019.1679315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mokuau N, DeLeon PH, Kaholokula JK, Soares S, Tsark JU, Haia C. Challenges and promise of health equity for Native Hawaiians. Washington, D.C.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godinet MT, Vakalahi HO, Mokuau N. Transnational Pacific Islanders: Implications for social work. Soc Work. 2019;64(2):113–21. doi: 10.1093/sw/swz003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vakalahi HO, Godinet MT, Fong R. Pacific Islander Americans: Impact of colonization and immigration. In: Fong R, McRoy R, Hendricks CO, editors. Intersecting child welfare, substance abuse, and family violence. Washington, D.C.: Council on Social Work Education Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamoto SK, Helm S, Poʻa-Kekuawela K, Chin CIH, Nebre LRH. Community risk and resiliency factors related to drug use of rural Native Hawaiian youth: An exploratory study. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2009;8(2):163–77. doi: 10.1080/15332640902897081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goebert D, Nahulu L, Hishinuma E, Bell C, Yuen N, Carlton B, et al. Cumulative effect of family environment on psychiatric symptomatology among multiethnic adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauricella M, Valdez JK, Okamoto SK, Helm S, Zaremba C. Culturally grounded prevention for minority youth populations: A systematic review of the literature. J Prim Prev. 2016;37(1):11–32. doi: 10.1007/s10935-015-0414-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaholokula JK, Ing CT, Look MA, Delafield R, Sinclair KA. Culturally responsive approaches to health promotion for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islander. Ann Hum Biol. 2018;45(3):249–63. doi: 10.1080/03014460.2018.1465593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaholokula JK, Look MA, Wills TA, de Silva M, Mabellos T, Seto TB, et al. Kā-HOLO Project: A protocol for a randomized controlled trial of a native cultural dance program for cardiovascular disease prevention in Native Hawaiians. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4246-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Patel S, Kwon S, Arista P, Tepporn E, Chung M, Chin KK, et al. Using evidence-based policy, systems, and environmental strategies to increase access to healthy food and opportunities for physical activity among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl. 3):S455–S8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *26.Kaholokula JK, Look M, Mabellos T, Zhang G, de Silva M, Yoshimura S, et al. Cultural dance program improves hypertension management for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders: A pilot randomized trial. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(1):35–46. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0198-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *27.Takishima-Lacasa JY, Kameoka VA. Adapting a sexually transmitted infection prevention intervention among female adolescents in Hawaiʻi. Health Promot Pract. 2018;20(4):608–15. doi: 10.1177/1524839918769592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fishbein DH, Ridenour TA, Stahl M, Sussman S. The full translational spectrum of prevention science: Facilitating the transfer of knowledge to practices and policies that prevent behavioral health problems. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0376-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *29.Cassel KD, Tran A, Murakami-Akatsuka L, Tanabe-Hanzawa J, Burnett T, Lum C. Adapting a skin cancer prevention intervention for multiethnic adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2018;42(2):36–49. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.42.2.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Okamoto SK, Helm S, Chin SK, Hata J, Hata E, Okamura KH The implementation of a culturally grounded, school-based, drug prevention curriculum in rural Hawaiʻi. J Community Psychol. 2020;48(4):1085–99. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okamoto SK. Academic marginalization? The journalistic response to social work research on Native Hawaiian youths. Soc Work. 2010;55(1):93–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mokuau N, Garlock-Tuialiʻi J, Lee P. Has social work met its commitment to Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders? A review of the periodical literature. Soc Work. 2008;53(2):115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *33.Abe Y, Barker LT, Chan V, Eucogco J. Culturally responsive adolescent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection prevention program for middle school students in Hawaiʻi. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(Suppl. 1):S110–S6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *34.Helm S, Lee W, Hanakahi V, Gleason K, McCarthy K, Haumana. Using photovoice with youth to develop a drug prevention program in a rural Hawaiian community. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2015;22(1):1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *35.Ing CKMT, Miyamoto RES, Antonio M, Zhang G, Paloma D, Basques D, et al. The PILI@Work Program: A translation of the Diabetes Prevention Program to Native Hawaiian-serving worksites in Hawaiʻi. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6:190–201. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0383-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *36.Ing CT, Zhang G, Dillard A, Yoshimura SR, Hughes C, Palakiko D-M, et al. Social support groups in the maintenance of glycemic control after community-based intervention. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *37.Ing CT, Miyamoto RES, Fang R, Antonio M, Paloma D, Braun KL, et al. Comparing weight loss-maintenance outcomes of a worksite-based lifestyle program delivered via DVD and face-to-face: A randomized trial. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(4):569–80. doi: 10.1155/2016/7913258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *38.Kaʻopua LSI, Cassel K, Shiramizu B, Stotzer RL, Robles A, Kapua C, et al. Addressing risk and reluctance at the nexus of HIV and anal cancer screening. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17(1):21–30. doi: 10.1177/1524839915615611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *39.Okamoto SK, Kulis S, Helm S, Lauricella M, Valdez JK. An evaluation of the Hoʻouna Pono curriculum: A pilot study of culturally grounded substance abuse prevention for rural Hawaiian youth. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(2):815–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *40.Okamoto SK, Helm S, Ostrowski LK, Flood L. The validation of a school-based, culturally grounded drug prevention curriculum for rural Hawaiian youth. Health Promot Pract. 2018;19(3):369–76. doi: 10.1177/1524839917704210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *41.Okamoto SK, Kulis SS, Helm S, Chin SK, Hata J, Hata E, et al. An efficacy trial of the Hoʻouna Pono drug prevention curriculum: An evaluation of a culturally grounded substance abuse prevention program in rural Hawaiʻi. Asian Am J Psychol. 2019;10(3):239–48. doi: 10.1037/aap0000164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]