Abstract

Decellularized organs have the potential to be used as scaffolds for tissue engineering organ replacements. The mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) following decellularization are critical for structural integrity and for regulation of cell function upon recellularization. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) accumulate in the ECM with age and their formation is accelerated by several pathological conditions including diabetes. Some AGEs span multiple amino acids to form crosslinks that may alter the mechanical properties of the ECM. The goal of this work was to evaluate how sugar-induced modification to the ECM affect the mechanical behavior of decellularized kidney. The compressive and tensile properties of the kidney ECM were evaluated using an accelerated model AGE formation by ribose. Results show that ribose modifications significantly alter the mechanical behavior of decellularized kidney. Increased resistance to deformation corresponds to increased ECM crosslinking, and mechanical changes can be partially mitigated by AGE inhibition. The degree of post-translational modification of the ECM is dependent on the age and health of the organ donor and may play a role in regulating the mechanical properties of decellularized organs.

Keywords: extracellular matrix, elastic modulus, decellularized organ, tissue engineering, advanced glycation end-product, kidney

1. Introduction

End-stage organ failure is a major cause of mortality worldwide. In the United States, loss of vital organ function due to fibrotic disease is estimated to account for 45% of deaths (Wynn, 2004). Organ transplant is a viable option, but the demand far outweighs the supply of transplantable organs. The kidney is one case in which living donor transplant is possible and is the preferred method of treatment for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (Davis and Delmonico, 2005). Even so, only around 30% of ESRD patients receive a transplant. Given this disparity between the need and availability of donor organs for the kidney and other vital organs, new regenerative medicine approaches to tissue replacement have emerged and have the potential to bridge this gap.

Potential strategies to replace kidney function include use of decellularized organs or three-dimensional bio-printed matrices for tissue engineering (Lin et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2020; Uzarski et al., 2014) and development of an artificial kidney (Kim et al., 2014; Salani et al., 2018). Decellularized organs have been explored for tissue engineering of heart, lung, liver, kidney and other vital organs and tissues (Mazza et al., 2015; Ott et al., 2008; Price et al., 2010; Song et al., 2013). Decellularized organs can then be recellularized with either autologous cells or stem cells to replace organ function (Scarritt et al., 2015). While several technical and biological hurdles remain in order to translate these techniques to clinical application, these approaches have the potential to significantly reduce donor organ scarcity.

The mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) following decellularization are important both for maintaining the mechanical integrity of the organ and for providing biophysical signals to cells upon recellularization. Multiple physical and/or chemical methods have been employed for removal of cellular material from tissues or whole organs (Crapo et al., 2011; Gilbert et al., 2006; He and Callanan, 2013). Decellularization with detergents is a commonly used technique for disruption and removal of cellular material. The three-dimensional architecture of organs can be largely retained following decellularization, although the method of tissue processing can have varying effects on tissue structure, composition, and mechanical properties (Chani et al., 2017; Gilbert et al., 2006; Melo et al., 2014; Simsa et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2014). Importantly, the structure of the vascular network can be maintained, a critical step both for facilitating recellularization and for proper organ function (Pellegata et al., 2018; Sullivan et al., 2012). In addition to structural integrity, the mechanics of the matrix are important for regulating the function of the cells upon recellularization. Matrix mechanics regulates cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation, all of which are important for proper function following recellularization (Discher et al., 2005; Hadjipanayi et al., 2009; Scarritt et al., 2015; Wells, 2008; Yeung et al., 2005) . Additionally, deviations from physiological stiffness can induce pathological cell responses (Huang et al., 2012; Lampi and Reinhart-King, 2018; Liu et al., 2010). For approaches employing recellularization of tissue scaffolds with stem cells, the mechanical properties of the ECM are critical regulators of cell stem lineage determination and differentiation (Alsberg et al., 2006; Das et al., 2016; Engler et al., 2006). Giving the multiple effects of matrix mechanics on the potential function of engineered tissues, identifying and characterizing factors that affect matrix mechanics and cellular function upon recellularization is an important step in furthering this potentially transformative technology.

A consideration that may be overlooked, particularly in pre-clinical animal studies, is the age and health status of the donor organ. Long-lived proteins including those in the ECM are particularly susceptible to post-translation modifications. Particularly, formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) is pathologically significant to the aging progress and in chronic diseases such as diabetes (Ramasamy et al., 2005; Sell et al., 2005). AGEs form through the reaction of sugars or other reactive carbonyls with proteins, resulting in a diverse range of biochemical adducts and crosslinks. Formation of AGE crosslinks in the ECM may be one factor that alters cellular behavior by altering the mechanical properties of the decellularized organs. Given the importance of ECM stiffness in regulating cell behavior, understanding the mechanical behavior of decellularized tissue is an important consideration for their use in tissue engineering approaches. Natural and/or disease processes that alter the mechanical properties of the ECM may need to be considered as an important factor in regulating cell differentiation and function in recellularized organs. We previously developed techniques for measuring the microscale mechanical properties of individual kidney glomerular matrix and tubular basement membrane and showed that sugars modify the mechanical response of these functional components of the kidney (Sant et al., 2020). The goal of this study was to evaluate the mechanical behavior of decellularized kidneys to evaluate the role of AGE crosslinking on the mechanical properties of the ECM as they relate to tissue engineering approaches to kidney regeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Decellularization of Kidney Cortex

Porcine kidneys from 6-month-old Yorkshire breed pigs were obtained from Lampire Biologicals (Pipersville, PA). Kidney cortex was cut into uniform sections using a meat slicer. The cortex was incubated in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) with 0.02% sodium azide with gentle agitation. SDS was changed daily until kidneys were translucent and showed no signs of residual cellular material. Decellularized cortex was then washed with deionized water three times for one hour each then overnight for five days with gentle agitation to remove residual SDS. Decellularized kidney cortex was modified by incubation in ribose at varying concentrations (0, 5, 30, and 100 mM) in phosphate buffer for 4 weeks at 37°C. For AGE inhibition studies, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA, Sigma Aldrich) and pyridoxamine (PM, Sigma Aldrich) were added to the incubation buffer at 10 or 20 mM concentrations, respectively.

2.2. Immunofluorescence Staining

To evaluate the structure of the decellularized kidney, ECM was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes on ice followed by three washes in PBS. Decellularized kidney ECM was then embedded in Histogel (Fisher Scientific) at 65°C for 30 minutes to aid in tissue sectioning. Histogel embedded decellularized kidney was then paraffin-embedded and processed by standard histological techniques. Tissue sections were deparaffinized, subjected to antigen retrieval, blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA), and probed with rabbit Collagen IV (1:300, ab6586 Abcam) or rabbit Laminin (1:100 ab11575 Abcam) antibodies. Sections were washed and probed with secondary anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 or 555 and mounted in mounting media with DAPI.

2.3. Western Blotting

Western blotting of cellular and ECM fractions was performed to determine the efficiency of decellularization and evaluate the retention of structural proteins in the ECM. Detergent extracted cellular fractions were collected and protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (BioRad). Decellularized ECM was lyophilized and powdered under liquid nitrogen. Cellular and ECM fractions were reduced in sample buffer with 8% β-mercaptoethanol at 70°C for 20 minutes. ECM fractions were centrifuged to pellet insoluble matrix. Cellular and ECM fractions were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in tri-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) and probed with primary antibodies for Laminin, Collagen IV, rabbit Lamin B (ab16048 Abcam), and mouse β-actin (sc47778 Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Membranes were washed three times with TBST and probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and imaged on a ChemiDoc MP imaging system (BioRad).

2.4. Compression Testing

The compressive modulus of native and ribose modified decellularized ECM with and without AGE inhibitors was measured using the Enduratec Electroforce 3100 testing system (Bose, Eden Prairie, MN) in a similar manner to that described previously (Barnes et al., 2007). Following decellularization, ECM samples were cut into circular disk (5 mm radius) using a leather punch. The system was fitted with a 50g load cell with1.5 mm radius indentation tip and measurements were obtained at an indentation depth of 0.4 mm. The indentation was performed for two minutes to damp the viscous component of the response. The average force from the final five data points in the force versus time plots was used to calculate the compressive modulus. The modulus was calculated according to the Stevanocic et al. (Stevanovic et al., 2001) model of contact between a rigid sphere and an elastic layer given by equation 1

| (1) |

where c1, c2, and c3, are correlation constants defined by Stevanocic et al. as c1=−1.73, c2=0.734, and c3=1.04, t is the sample thickness, ρ is the radius of the indenter tip, d is the indentation depth, υ is Poisson’s ratio which was taken as 0.45, E is the elastic modulus, and F is the applied force. ECM sample thickness was generally 3-4 mm, and thickness was measured for each sample using a caliper prior to testing. Measurements were performed on four samples per experimental condition.

2.5. Tensile Testing

Tensile testing was performed using a planar biaxial soft tissue testing system (Instron). Decellularized cortical ECM samples were cut into dog-bone shapes using a biopsy punch to create samples approximately 5 mm long, 2 mm wide, and 3 mm thick. Sample geometries were measured individually to determine the cross-sectional area. Testing was performed in uniaxial tension at a constant displacement rate of 1 mm/min. Measurement were performed on 3-4 experimental replicates per condition.

2.6. Hyperelastic Modeling of Tensile Response

To model the stress-strain response, multiple hyperelastic models were employed. The equations employed for the Neo-Hookean, Mooney-Rivlin, Humphrey, Veronda-Westmann, and Yoeh models were the functional forms described by Martins et al.(Martins et al., 2006) Experimental data were fit to the models using non-linear least squares curve fitting in Excel (Harris, 1998). The quality of the fit was evaluated by calculating the correlation coefficient (Fitzpatrick et al., 2010).

2.7. Biochemical Characterization

ECM fluorescence and pentosidine concentrations were measured in native and ribose-modified ECM. Native and glycated ECM was lyophilized and approximately 5 mg (dry weight) of ECM was hydrolyzed for 20 hours in 6M HCl at 110°C. Hydrolyzed ECM was concentrated on a Speedvac. Dehydrated samples were re-dissolved in deionized (DI) water then filtered through a 0.2 μm syringe filter. Fluorescence analysis was performed on a plate reader (Promega Glomax Discover) with an excitation wavelength of 365 nm and an emission wavelength of 415-445 nm. For pentosidine analysis, samples were analyzed by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)(Creecy et al., 2016). Separations were performed on an Agilent 1200 HPCL system using a C18 column (Phenomenex Widepore 150) at a flow rate of 1.2 ml/min with a column temperature of 40°C. Mobile phase A was 0.22% heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) and mobile phase B was 100% acetonitrile. A linear gradient of mobile phase B was ramped from 5% to 75%. The total run time was 7 minutes. Pentosidine was analyzed using a fluorescence detector with an excitation at 328 nm and an emission at 378 nm. Calibration curves were generated for each sample set using commercially available pentosidine (Cayman Chemicals). Pentosidine concentrations were normalized to the dry mass of ECM. Measurements of ECM fluorescence and pentosidine concentrations were performed on n=3 samples per condition.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data were evaluated by one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Dunnett’s testing to evaluate difference relative to the control. Statistical significance was taken as p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Decellularized Kidney Cortex

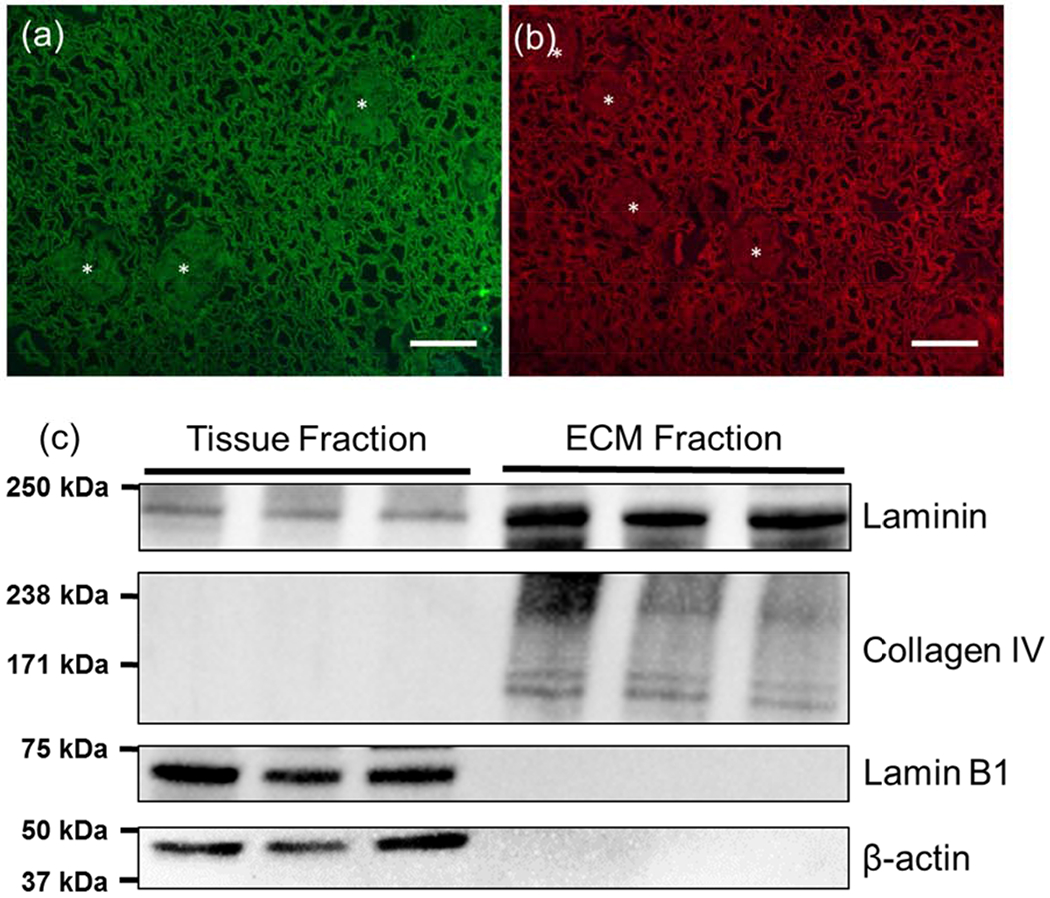

Immunofluorescence (IF) imaging for structural ECM proteins (collagen IV and laminin) in the decellularized kidneys showed the three-dimensional architecture of the matrix was largely retained with well-defined tubules and glomeruli (Figure 1 a–b). Glomeruli are indicated with asterisks and tubular lumens are clearly visible in the images. Counterstaining with DAPI showed minimal residual nuclear material in the decellularized tissue. Western blot analysis of the detergent extracted tissue fraction and the decellularized ECM fraction showed that Lamin B1, a nuclear protein, and β-actin, a cytoskeletal component, were efficiently extracted from the tissue with no detectable cellular proteins in the ECM fraction. Laminin and collagen IV were retained in the ECM with a detectable laminin band in the tissue fraction that was either derived from the cellular compartment or a small amount of mature laminin may have been detergent extracted. No collagen IV was detected in the tissue fraction.

Figure 1.

Characterization of decellularized kidney cortex. (a,b) Collagen IV and laminin immunofluorescence images from decellularized cortex. Matrix showed minimal residual nuclear material based on counterstaining with DAPI. Scale bar=100 μm (c) Western blot analysis of laminin, collagen IV showing that structural ECM proteins are retained in the matrix following decellularization. Some laminin was extracted in the tissue fraction but was largely retained in the insoluble ECM fraction. Nuclear (Lamin B1) and cytoskeletal (β-actin) proteins were found in the tissue fraction but were not detected in the ECM fraction.

3.2. Compression Testing of Decellularized Kidney

Equilibrium compressive modulus was measured at a fixed indentation depth (0.4 mm). Stress relaxation curves showed a reduction in force over time that was largely damped after two minutes (Figure 2). The indentation force was significantly higher in the ribose modified ECM compared to native ECM. This increase in force was partially mitigated using AGE inhibition with DTPA and PM.

Figure 2.

Stress relaxation curves for native and ribose (30 mM) modified kidney ECM at constant indentation depth (0.4 mm). Steady state force was increased in ribose modified ECM. AGE inhibitors DTPA and PM reduced steady state force. Data are shown as mean (solid line) ± SEM (dotted line), n=4 for all conditions.

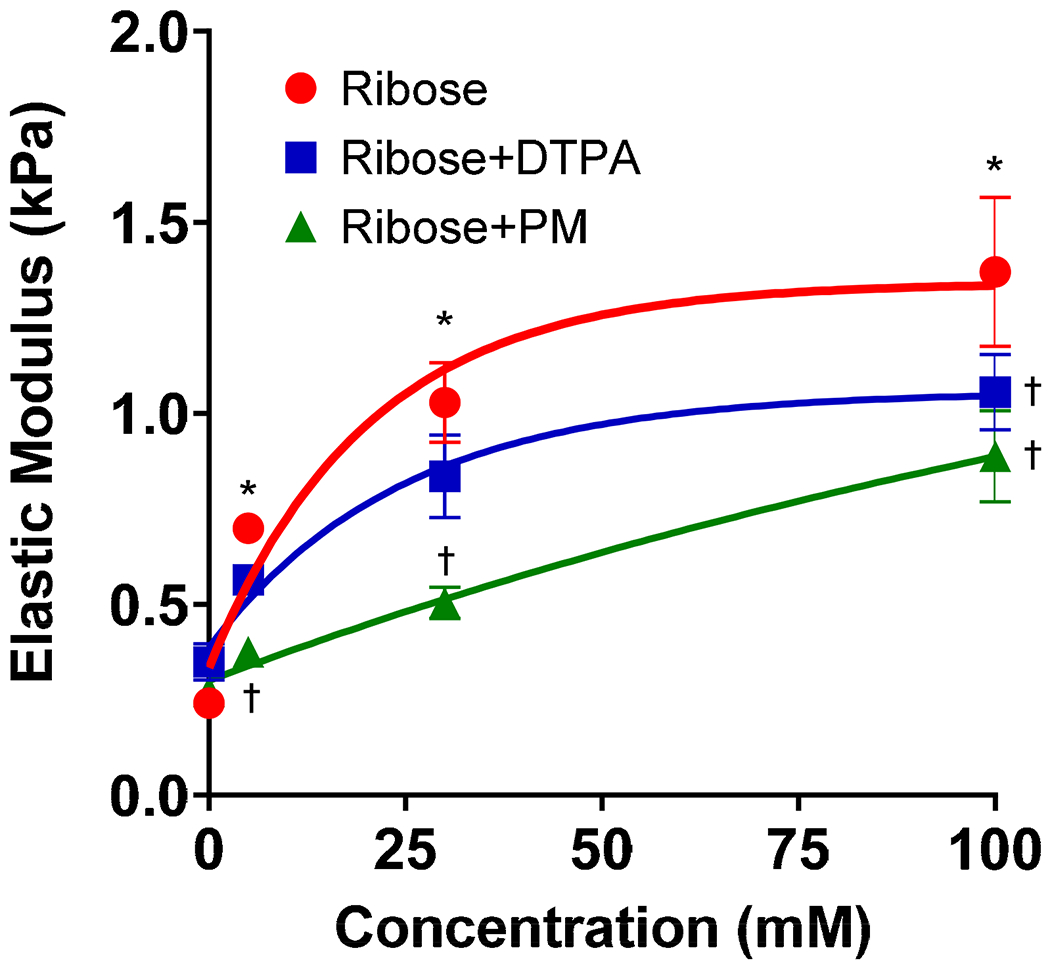

Compressive stiffness was measured at varying ribose concentrations (0-100 mM) in the presence of DTPA and PM. Ribose induced a dose-dependent increase in stiffness (Figure 3) with approximately a doubling of elastic modulus at low ribose concentration (5 mM) and a 4.5 fold increase in stiffness at the highest ribose concentration (100 mM) as compared to native controls. DTPA trended toward reducing ECM stiffness, but only reached a statistically significant difference from ribose modification at the highest ribose concentration (100 mM). PM significantly reduced ECM stiffness at all ribose concentrations.

Figure 3.

Elastic modulus for ribose modified kidney ECM versus ribose concentration with and without AGE inhibitors DTPA (10 mM) and PM (20 mM). Ribose incubation increased ECM stiffness in a dose-dependent manner. Post-hoc Dunnett’s testing for multiple comparisons was used to evaluate differences from the control. * denotes statistically significant differences in elastic modulus induced by ribose relative to control. † denotes statistically significant reductions in stiffness as compared to ribose at a given concentration, n=4 for all conditions. The solid line is the least squares fit of the data to an exponential function of the form y=c1+c2(1-e−c3x). DTPA and PM reduced ribose induced increases in ECM stiffness. PM reduced ECM stiffness at all concentrations. DTPA reduced ECM stiffness in a statistically significant manner at 100 mM ribose. Data are shown at the mean±SEM. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Solid lines are best-fit curves based on an exponential function.

3.2. Tensile Testing of Decellularized Kidney

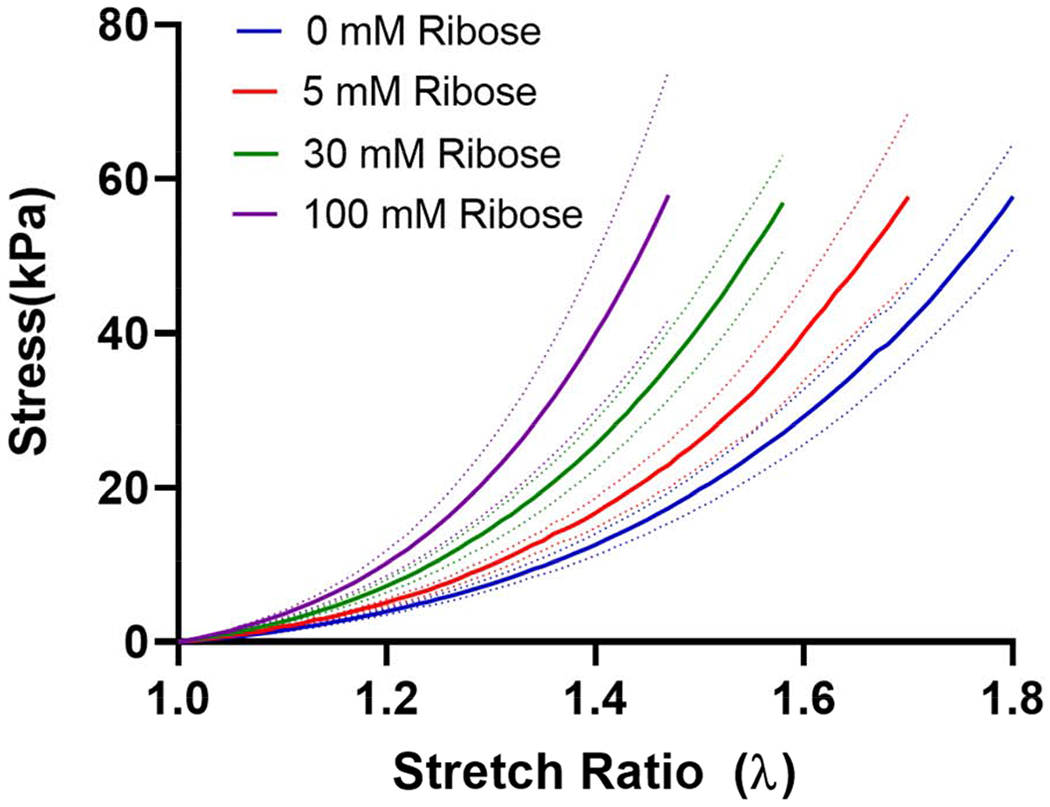

ECM stress-strain response in ribose modified ECM was measured in tension. Stress versus stretch ratio (ratio of deformed to undeformed length) showed that the unmodified ECM exhibited significantly non-linearity in the mechanical response (Figure 4). Ribose modification induced a dose-dependent upward shift in the stress-stretch curve indicating an increase in the stress required to induce an equivalent dimensional change in the matrix.

Figure 4.

Stress versus stretch ratio for kidney ECM at varying ribose concentrations. Increasing ribose concentrations resulted in an upward shift in the stress-stretch ratio curve. Data are shown as the mean (solid line) ± SEM (dotted lines), n=3 for 5 and 30 mM ribose, n=4 for 0 and 100 mM ribose.

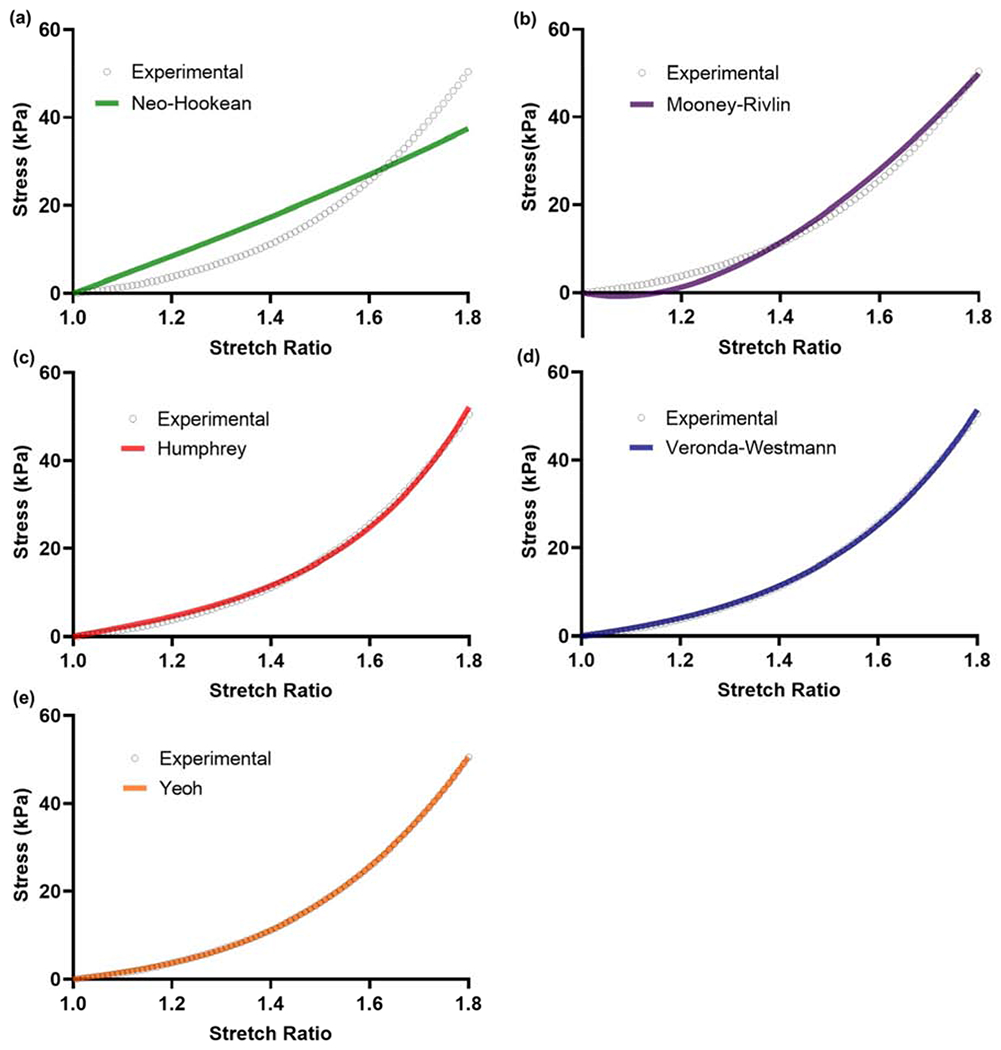

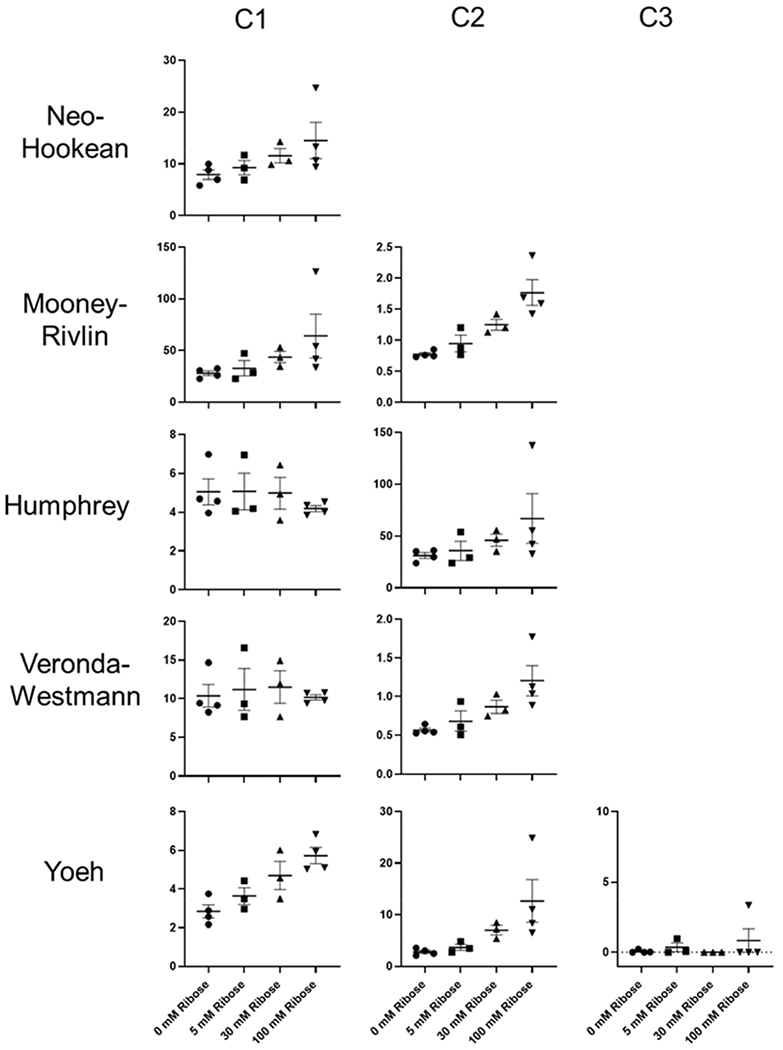

3.3. Hyperelastic models of kidney ECM

Several hyperelastic material models were evaluated to describe the stress-stretch response of the native and ribose modified ECM in tension. Representative model fits to experimental data for each of the hyperelastic models are shown in Figure 5. The Neo-Hookean model showed considerable deviation from the experimental data. The Mooney-Rivlin model deviated from experimental data at low stretch ratio but fit well with the data at higher levels of stretch. All other hyperelastic models were in good agreement with the experimental data. Curve fitting parameters for each of the models for native and ribose modified matrix are given in Figure 6. Data showed a general increase in the value of the fit parameters with increasing ribose concentration, which is consistent with the upward shift in the stress-stretch response. Exceptions to this trend were seen in the models with both non-exponential and exponential terms (Humphrey and Veronda-Westmann). In these two models, the non-exponential term (c1) was largely unchanged while the exponential term (c2) increased as a function of elevated ribose concentration. Additionally, for the Yeoh model, the third term in the model (c3) had little effect on the quality of the fit. The correlation coefficients (C.C.) for each of the hyperelastic models for native and ribose modified ECM are given in Table 1. These data show that the models are similarly good fits to the sugar modified ECM. The Neo-Hookean model gives the lowest C.C. whereas the Humphrey, Veronda-Westmann, and Yeoh models had C.Cs that approached one indicating minimal deviation between the model fits and the experimental data.

Figure 5.

Hyperelastic model fit examples to experimental data for native kidney ECM using least-square error curve fitting. Yeoh, Veronda-Westamnn, and Humphrey models gave excellent fits to the experimental data. The Mooney-Rivlin model was a reasonable fit at higher stretch ratios. The Neo-Hookean model did not fit well with the experimental data. Correlation coefficients for the model fits to native and ribose modified ECM are shown in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Fit parameters for hyperelastic models. In general, the fit parameters increased with increasing ribose concentration. Exceptions were the c1 (non-exponential term) in the Humphrey and Veronda-Westmann models. For these models, the exponential (c2) term in the model increased with increasing ribose concentration. For the Yeoh models, c1 and c2 increased with increasing ribose concentration. The c3 term in the model had little effect on the model fit.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients for the model fits to native and ribose modified kidney ECM.

| Ribose Concentration (mM) | Neo-Hookean | Mooney-Rivlin | Humphrey | Veronda-Westmann | Yeoh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n=4) | 0.9651±.0025 | 0.9965±.0007 | 0.9990±.0002 | 0.9996±.0002 | 0.9999±.0001 |

| 5 (n=3) | 0.9640±.0085 | 0.9960±.0019 | 0.9991±.0003 | 0.9997±.0002 | 0.9997±.0001 |

| 30 (n=3) | 0.9678±.0040 | 0.9978±.0007 | 0.9988±.0003 | 0.9996±.0002 | 0.9998±.0001 |

| 100 (n=4) | 0.9677±.0065 | 0.9979±.0009 | 0.9989±.0002 | 0.9996±.0001 | 0.9998±.0001 |

Data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM)

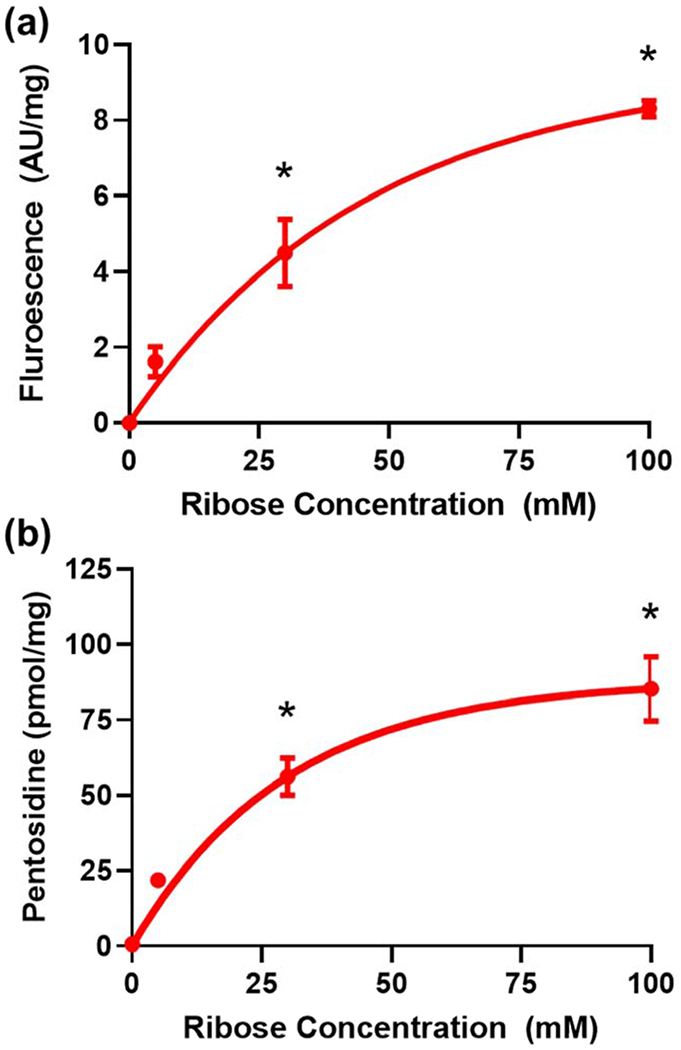

3.4. Biochemical analysis of matrix crosslinking

To evaluate crosslinking of the ECM, biochemical analysis was performed to measure ECM fluorescence and pentosidine concentration (Figure 7). ECM fluorescence increased in a dose-dependent manner with increasing ribose concentration. This is consistent with the formation of acid stable fluorescent AGEs (Nakamura et al., 1997). To evaluate specific crosslink formation, pentosidine was measured by HPLC and showed a similar trend of increased concentration with increasing ribose concentration.

Figure 7.

Biochemical characterization of the ECM showed (a) increased fluorescence as a function of increasing ribose concentration indicating increases in AGE formation. (b) Analysis of pentosidine crosslink concentrations in the matrix showed an increase in pentosidine with increasing ribose concentration. The solid lines are the least squares fit of the data to an exponential function of the form y=c1(1-e−c2x). * denotes statistically significant differences as compared to the native ECM. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s testing, n=3 for all conditions. Solid lines are best-fit curves based on an exponential function

4. Discussion

The extracellular matrix is a critical component of many tissue engineering and regenerative medicine approaches. Particularly for using whole decellularized organs as tissue scaffolds, age or disease-mediated biochemical and biophysical alterations to the ECM may have important consequences for cell differentiation and function. This could be related to receptor-mediated effects in combination with changes in the mechanical properties of the matrix. These properties may vary considerably depending on the age and health of the donor scaffold and this may need to be considered as an important factor regulating how cells respond and function upon recellularization. A better understanding of the many factors that contribute to cell function in tissue scaffolds may help overcome the obstacles to bringing regenerative medicine approaches to clinical application.

Post-translation modifications to the ECM are important regulators of cell behavior and have been implicated in disease progression (Randles et al., 2017). AGEs have long been recognized as pathological contributors to multiple conditions including aging, diabetes, and neurological conditions (Ramasamy et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2001). AGEs act through multiple mechanisms. Receptor-mediated effects include binding the cellular receptor for AGEs (RAGE) to elicit pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cellular pathways that contribute to disease pathology (Ramasamy et al., 2011). Non-receptor effects include a reduction in ECM susceptibility to degradation that reduces ECM turnover and may contribute to ECM accumulation (Mott et al., 1997). AGE-mediated crosslinking and associated stiffening of the ECM may contribute to cellular dysfunction and could represent an additional mechanism by which AGEs exert pathological consequences. These effects may need to be considered in the context of the age and health of donor organs for regenerative medicine.

To evaluate how AGE formation alters the mechanics of decellularized kidney, we modified renal cortical matrix with varying concentrations of ribose (0-100 mM) to model time and/or concentration-dependent formation of AGEs in the ECM. While serum ribose concentrations do increase in diabetes (Yu et al., 2019) and contribute to modification of serum proteins (Yao et al., 2019), concentrations of ribose are significantly lower than glucose. Glucose is likely a more physiologically relevant long-term driver of AGE formation. We chose to modify the kidney matrix with ribose primarily due to the slow reaction rate between glucose and amine groups on proteins. While formation of glucose adducts such as carboxymethyl lysine (CML) can form relatively quickly in vitro (Voziyan et al., 2003), formation of stable glucose derived AGE crosslinks can take months to run to completion in vitro and elevated concentrations of glucosepane crosslinks in vivo require years to be detected in the kidney matrix (Monnier et al., 2014; Sell et al., 2005). As such, it is common in biochemical studies of AGE formation to use similar ribose concentrations to accelerate AGE formation and perform studies in shorter time frames (Khalifah et al., 1996; Valcourt et al., 2006). While ribose is an attractive alternative to glucose for performing in vitro studies in reasonable time frames, it is noteworthy that the biochemical nature of the AGEs that are formed by different sugars are distinct (Sroga et al., 2015). Ribose modification primarily drives pentosidine formation while glucose derived glucosepane crosslinks are prominent in vivo (Sell et al., 2005). While both ribose and glucose derived crosslinks likely alter the physical properties of the ECM (Nash et al., 2019; Vashishth et al., 2001), it is not clear if the biochemical nature of the crosslink is a primary factor in how it affects matrix mechanics or if the ECM concentration of the crosslink is the primary driver of increased stiffness. Additionally, the role of intermolecular versus intramolecular crosslinks in driving changes in matrix mechanics is not clear.

AGE inhibition has shown promise in animal models of diabetic kidney disease. The mechanisms of action of AGE inhibitors are not completely understood. The beneficial effects have been hypothesized to be due to both inhibition of receptor-mediated effects and antioxidant effects (Nagai et al., 2012). We aimed to determine if AGE inhibition also had effects on AGE-mediated stiffening of the matrix. Pyridoxamine, which has shown to reduce kidney damage in animal models of diabetic nephropathy (Anderson et al., 2003; Degenhardt et al., 2002; Voziyan and Hudson, 2005), showed significant inhibition of AGE mediated stiffening of the ECM (Figure 3). While it is not yet clear if this ability to mitigate changes in ECM stiffness is physiologically relevant, these data suggest that reductions in AGE-mediated stiffening of the matrix may represent an additional mechanism by which AGE inhibition reduces the pathological consequences of AGE formation.

Non-linearity in the stress-stretch response for the cortical ECM in tension is clearly demonstrated in Figure 4. This increase in resistance to deformation with increased strain has been demonstrated in biopolymer networks and in both native and decellularized soft tissue (Fitzpatrick et al., 2010; Motte and Kaufman, 2013; Storm et al., 2005; Zhou and Fung, 1997). Little work has focused on hyperelastic mechanical behavior of decellularized kidney. Modeling of the experimental data with well-established hyperelastic theory shows that these models are well-suited for analysis of decellularized organ mechanics. These models have been well established for modeling soft tissue biomechanics (Chagnon et al., 2015; Martins et al., 2006; Mihai et al., 2015) but have not been applied extensively to the evaluation of decellularized organ mechanics. We found that the models were similarly applicable to characterization of decellularized kidney mechanics.

Biochemical analysis of AGE formation following ribose modification showed that increased ECM stiffness correlated with an increase in both matrix fluorescence and elevated concentrations of pentosidine crosslinks. Tissue fluorescence is often used as a general measure of AGE formation due to the simplicity of the measurement. Fluorescence data is consistent with a dose response in AGE formation with increasing ribose concentration. However, fluorescence is a non-specific measure of AGE formation and does not reflect levels of any particular crosslink. To specifically analyze a known physiologically relevant crosslink (Sell et al., 1992), pentosidine concentrations were measured. Ribose modified ECM gave a similar dose-dependent response, suggesting that AGE-mediated crosslinking contributes to the observed changes in ECM mechanical behavior in sugar modified matrix.

5. Conclusions

The mechanical properties of the ECM are critical to proper cell function in many tissue engineering scaffolds, including decellularized organs. Understanding the factors that modify matrix properties is important for predicting and understanding how cells will function in natural ECM scaffolds. One factor that regulates matrix mechanics is advanced glycation, which results in matrix crosslinking. Here we show that sugar-induced modification of the ECM increases matrix stiffness in a dose-dependent manner. This response can be partially mitigated by AGE inhibition, suggesting that AGEs mediate this stiffening process and inhibiting AGE formation may normalize matrix mechanical properties. This work further shows that the hyperelastic models of materials behavior are effective in modeling the tensile properties of native and sugar modified ECM.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) K01 DK092357, R03 DK110399, Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar Award from the American Society of Nephrology, and a pilot and feasibility grant from the Vanderbilt Center for Kidney Disease. The authors would like to thank Dr. Michael Miga and Dr. Jared Weis (Vanderbilt University, Department of Biomedical Engineering) for use of the Electroforce measurement system. We would also like to thank David Nedrelow (University of Minnesota, Tissue Mechanics Laboratory) for technical assistance with the Instron Biaxial Tension Tester and Sylvia Verhoven for technical assistance with HPLC analysis of pentosidine concentrations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Alsberg E, Recum H.A.v., Mahoney MJ, 2006. Environmental cues to guide stem cell fate decision for tissue engineering applications. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 6, 847–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NL, Chachich ME, Youssef NN, ettie RJ, Nachtigal M, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW, 2003. The AGE inhibitor pyridoxamine inhibits lipemia and devlopement of renal and vascular disease in Zucker obese rats. Kidney Int 63, 2123–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes SL, Lyshchik A, Washington MK, Gore JC, Miga MI, 2007. Development of a mechanical testing assay for fibrotic murine liver. Med. Phys 34, 4439–4450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagnon G, Rebouah M, Favier D, 2015. Hyperelastic energy densities for soft biological tissues: a review. J. Elast 120, 129–160. [Google Scholar]

- Chani B, Puri V, Sobti RC, Jha V, Puri S, 2017. Decellularized scaffold of cryopreserved rat kidney retains its recellularization potential. PLoS One 12, e0173040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crapo PM, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF, 2011. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials 32, 3233–3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creecy A, Uppuganti S, Merkel AR, O’Neal D, Makowski AJ, Granke M, Voziyan P, Nyman JS, 2016. Changes in the fracture resistance of bone with the progression of type 2 diabetes in the ZDSD rat. Calcif. Tissue Int 99, 289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das RK, Gocheva V, Hammink R, Zouani OF, Rowan AE, 2016. Stress-stiffening-mediated stem-cell commitment switch in soft responsive hydrogels. Nat. Mater 15, 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CL, Delmonico FL, 2005. Living-donor kidney transplantation: A review of the current practices for the live donor. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 16, 2098–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt TP, Alderson NL, Arrington DD, Beattie RJ, Basgen JM, Steffes M.w., Thorpe SR, Baynes JW, 2002. Pyridoxamine inhibits early renal disease and dyslipidemia in the streptozotocin-diabetic rat. Kidney Int 61, 939–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang Y.-l., 2005. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science 310, 1139–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE, 2006. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126, 677–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick JC, Clark PM, Capaldi FM, 2010. Effect of decellularization protocol on the mechanical behavior of porcine descending aorta. Int. J. Biomater 2010, 620503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert TW, Scllaro TL, Badylak SF, 2006. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials 27, 3675–3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjipanayi E, Mudera V, Brown RA, 2009. Close dependence of fibrobalst proliferation on collagen scaffold matrix stiffness. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med 3, 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris DC, 1998. Nonlinear least-squares curve fitting with Microsoft Excel solver. J. Chem. Educ 75, 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- He M, Callanan A, 2013. Comparison of methods for whole-organ decellularization in tissue engineering of bioartificial organs. Tiss. Eng. Part B 19, 194–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Yang N, Fiore VF, Barker TH, Sun Y, Morris SW, Ding Q, Thannickal VJ, Zhou Y, 2012. Matrix stiffness-induced myofibroblast differentation is mediated by intrinsic mechanotransduction. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 47, 340–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifah RG, Todd P, Booth AA, Yang SX, Mott JD, Hudson BG, 1996. Kinetics of nonenzymatic glycation of ribonuclease A leading to advanced glycation end products. Paradoxial inhibition of ribose leads to facile isolation of protein intermediates for rapid post-Amadori studies. Biochemistry 35, 4645–4654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Fissell WH, Humes HD, Roy S, 2014. Current strategies and challenges in engineering a bioartificial kidney. Front. Biosci 7, 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampi M, Reinhart-King CA, 2018. Targeting extracellular matrix stiffness to attenuate disease: From molecular mechanisms to clinical trails. Sci. Trans. Med 10, eeo0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin NYC, Homan KA, Robinson SS, Kolesky DB, Duarte N, Moisan A, Lewis JA, 2019. Renal reabsorption in 3D vasculared proximal tubule models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5399–5404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Mih JD, Shea BS, Kho AT, Sharif AS, Tager AM, Tschumperlin DJ, 2010. Feedback amplification of fibrosis through matrix stiffness and COX-2 suppresion. J. Cell Biol 190, 693–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins PALS, Jorge RMN, Ferreira AJM, 2006. A comparative study of several material models for prediction of hyperelastic properties: Application to silicone-rubber and soft tissues. Strain 42, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza G, Rombouts K, Hall AR, Urbani L, Loung TV, Al-Akkad W, Longato L, Brown D, Maghsoudlou P, Dhillon AP, Fuller B, Davidson B, Moore K, Dhar D, Coppi PD, Malago M, Pinzani M, 2015. Decellularized human liver as a natural 3D-scaffold for liver bioengineering and transplantation. Sci. Reports 5, 13079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo E, Garreta E, Luque T, Cortiella J, Nichols J, Navajas D, Farre R, 2014. Effects of the decellularization method on the local stiffness of acellular lungs. Tiss. Eng. Part C 20, 412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihai LA, Chin L, Janmey PA, Goriely A, 2015. A comparison of hyperelastic constitutive models applicable to brain and fat tissue. J. R. Soc. Interface 12, 20150486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier VM, Sun W, Sell DR, Fan X, Nemet I, Genuth S, 2014. Glucosepane: a poorly understood advanced glycation end product of growing importance for diabetes and its complications. Clin. Chem. Lab Med 52, 21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JD, Khalifah RG, Nagase H, III CFS, Hudson JK, Hudson BG, 1997. Nonenyzmatic glycation of type IV collagen and matrix metalloproteinase suseptibility. Kidney Int 52, 1302–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motte S, Kaufman LJ, 2013. Strain stiffening in collagen I networks. Biopolymers 99, 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai R, Murray DB, Metz TO, Baynes JW, 2012. Chelation: A fundamental mechanism of action of AGE inhibitors, AGE breakers, and other inhibitors of diabetes complications. Diabetes 61, 549–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Nakazawa Y, Ienaga K, 1997. Acid-stable fluorescent advanced glycation end products: Vesperlyines A,B, and C are formed as crosslinked products in the Maillard reaction between lysine or proteins with glucose. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 232, 227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash A, Notou M, Lopez-Clavijo AF, Bozec L, Leeuw N.H.d., Birch HL, 2019. Glucosepane is associated with changes to structural and physical properties of collagen fibrils. Matrix Biol. Plus 4, 100013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh S-K, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, Taylor DA, 2008. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature’s platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat. Med 14, 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegata AF, Tedeschi AM, Coppi PD, 2018. Whole organ tissue vascularization: engineering the tree to develop the fruits. Font. Bioeng. Biotechnol 6, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AP, England KA, Matson AM, Blazer BR, Panoskaltsis-Martari A, 2010. Development of a decellularized lung bioreactor system for bioengineering the lung: The matrix reloaded. Tiss. Eng. Part A 16, 2581–2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy R, Vannucci SJ, Yan SSD, Herold K, Yan SF, Schmidt AM, 2005. Advanced glycation end products and RAGE: a common thread in aging, diabetes, neurodegeneration, and inflammation. Glycobiology 15, 16R–28R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy R, Yan SF, Schmidt AM, 2011. Receptor for AGE (RAGE): signaling mechanisms in the pathogenesis of diabetes and its complications. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 1243, 88–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randles MJ, Humphries MJ, Lennon R, 2017. Proteomic definitions of basement membrane composition in health and disease. Matrix Biol 57-58, 12–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salani M, Roy S, Fissell WH, 2018. Innovations in wearable and implantable artificial kidneys. Am. J. Kidney Dis 72, 745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant S, Wang D, Agarwal R, Dillender S, Ferrell N, 2020. Glycation alters the mechanical behavior of kidney extracellular matrix. Matrix Biol. Plus in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarritt ME, Pashos NC, Bunnell BA, 2015. A review of cellularization strategies for tissue engineering of whole organs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 3, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell DR, Biemel KM, Reihl O, Lederer MO, Strauch CM, Monnier VM, 2005. Glucosepane is a major protein cross-link of the senescent human extracellular matrix: Relationship with diabetes. J. Biol. Chem 280, 12310–12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell DR, Lapolla A, Odetti P, Fogarty J, Monnier V, 1992. Pentosidine formation in skin correlates with severity of complications in individuals with long-standing IDDM. Diabetes 41, 1286–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simsa R, Padma AM, Heher P, Hellstrom M, Teuschl A, Jenndahl L, Bergh N, Fogelstrand P, 2018. Systematic in vitro comparison of decellularization protocol for blood vessels. Plos One 13, e0209269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NK, Han W, Nam SA, Kim JW, Kim JY, Kim YK, Cho D-W, 2020. Three-dimensional cell-printing of advanced renal tubular tissue analogue. Biomaterials 232, 119734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Barden A, Mori T, Beilin L, 2001. Advanced glycation end-products: a review. Diabetologia 44, 129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JJ, Guyette JP, Gilpin SE, Gonzalez G, Vacanti JP, Ott HC, 2013. Regenertion and experimental orthotopic transplantation of a bioengineered kidney. Nat. Med 19, 646–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroga GE, Siddula A, Vashishth D, 2015. Glycation of human cortical and cancellous bone captures differences in the formation of Maillard reaction products between glucose and ribose. PLOS One 10, e0117240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevanovic M, Yavanovich MM, Culham JR, 2001. Modeling contact between rigid sphere and elastic layer bonded to rigid substrate. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Technol 24, 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Storm C, Pastore JJ, MacKintosh FC, Lubensky TC, Janmey PA, 2005. Nonlinear elasticity in biological gels. Nature 435, 191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan DC, Mirmalek-Sani S-H, Deegan DB, Baptista PM, Aboushwareb T, Atala A, Yoo JJ, 2012. Decellularization methods of porcine kidneys for whole organ engineering using a high-throughput system. Biomaterials 33, 7756–7764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzarski JS, Xia Y, Belamonte JCI, Wertheim JA, 2014. New strategies in kidney regeneration and tissue engineering. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens 23, 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcourt U, Merle B, Gineyts E, Viguet-Carrin S, Dalmas PD, Garnero P, 2006. Non-enzymatic glycation of bone collagen modifies osteoclastic activity and differentation. J. Biol. Chem 282, 5691–5703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashishth D, Gibson GJ, Khoury JI, Schaffler MB, Kimura J, Fyhrie DP, 2001. Influence of non-enzymatic glycation on biomechanical properties of cortical bone. Bone 28, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voziyan PA, Hudson BG, 2005. Pyridoxamine as a multifunctional pharmaceutical: targeting pathogenic glycation and oxidative damage. Cell Mol Life Sci 62, 1671–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voziyan PA, Khalifah RG, Thibaudeau C, Yildiz A, Jacob J, Serianni AS, Hudson BG, 2003. Modification of proteins in vitro by physiological levels of glucose. J. Biol. Chem 278, 46616–46624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells RG, 2008. The role of matrix stiffness in regulating cell behavior. Hepatology 47, 1394–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn TA, 2004. Fibrotic disease and the TH1/TH2 paradigm. Nat. Rev. Immunol 4, 583–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Xu B, Yang Q, Li X, Ma X, Xia Q, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Wu Y, Zhang Y, 2014. Comparison of decellularization protocols for preparing a decellularized porcine annulus fibrosus scaffold. Plos One 9, e86723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Chen Y, Yu L, Wang Y, Wei Y, Xu Y, He T, He R, 2019. D-Ribose contributes to the glycation of serum protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Basis Dis 1865, 2285–2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung T, Georges PC, Flanagan LA, Marg B, Ortiz M, Funaki M, Zahir N, Ming W, Weaver V, Janmey PA, 2005. Effects of stubstrate stiffness of cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 60, 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Chen Y, Xu Y, He T, Wei Y, He R, 2019. D-ribose is elevated in T1DM patients and can be involved in the onset of encephalopathy. Aging 11, 4943–4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Fung YC, 1997. The degree on nonlinearlity and anisotropy of blood vessel elasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 14255–14260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]