Abstract

Longevity associated neurological disorders have been observed across human and canine aging populations. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome (CDS) represent comparable diseases affecting both species as they age. Translational diagnostic and therapeutic research is needed for these incurable diseases. The amyloid β (Aβ) peptide family are AD-associated peptides with identical amino acid sequence between dogs and humans. Plasma Aβ42 concentration increases with age and decreases with AD in humans, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentration decreases in AD and correlates inversely with the amyloid load within the brain. Similarly, CSF Aβ42 concentrations decrease in dogs with CDS but there is limited and conflicting information on plasma Aβ42 concentrations in aging dogs and dogs with CDS. We measured plasma concentrations of Aβ42 and Aβ40 with an ultrasensitive single-molecule array assay (SIMOA) in a population of healthy aging dogs of different life-stages (n=36) and dogs affected with CDS (n=11). In addition, the ratio of Aβ42/β40 was calculated. The mean plasma concentrations of Aβ42 and Aβ40 increased significantly with age (r2 =0.27, p=0.001 and r2 =0.42, p<0.001 respectively) and with life stage: puppy/junior group, (0.43–2 years): 1.23±0.95 and 38.26±49.43pg/mL; adult/mature group, (2.1– 9 years):10.99±5.45 and 131.05±80.17pg/mL; geriatric/senior group, (9.3–14.5 years):18.65±16.65 and 192.88±146.38pg/mL, respectively. Concentrations of Aβ42 and Aβ40 in dogs with CDS (11.0–15.6 years) were significantly lower than age matched healthy dogs at 11.61±6.39 and 150.23±98.2pg/mL, (p=0.0048 and p=0.001) respectively. Our findings suggest the dynamics of canine plasma amyloid concentrations are analogous to that found in aging humans with and without AD.

Keywords: canine, cognitive dysfunction, Alzheimer’s disease, CDS, amyloid-beta 42, amyloid-beta 40

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome (CDS) are comparable diseases affecting human and canine species as they age [1]. An AD epidemic is evolving across the globe and has been connected to an increased average life-expectancy [2]. Demographic studies have shown that aged pet dogs also suffer from age-associated neuro-degenerative processes [3, 4]. A core pathophysiological feature shared across human and canine species is spontaneously occurring amyloid β (Aβ) plaque deposition within the extracellular space in the brain, along with Aβ-induced neuronal and glial proteotoxicity [5]. The four-stage distribution of Aβ deposits within the cortical grey matter that has been described in people has been also identified in dogs using immunohistochemistry [6]. Importantly, the amino acid sequence of Aβ is identical between humans and dogs [7]. Brain pathology correlates with the severity of cognitive impairment in both species as described in several studies [8–12]. In humans with AD, there is a decrease in concentrations of Aβ within the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) which negatively correlate with amyloid load in the brain [13, 14]. Similarly, in beagle dogs with CDS, the concentrations of Aβ oligomers in the CSF are inversely correlated with Aβ deposition when assessed with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [15] or electrochemiluminescence detection technology [16].

Advances in minimally invasive blood-based biomarkers have enabled early screening for non-AD individuals at greatest risk for the development of AD. These biomarkers can be used as sensitive outcome measures in clinical trials and to analyze the therapeutic effect of experimental drugs [17]. Proteins such as Aβ42 and Aβ40 are a component of AD pathology and can be detected in blood. However ultrasensitive technologies are required for their reliable measurement [18]. Single molecule array assay (SIMOA) technology represents a novel, highly sensitive platform, that can detect thousands of single molecules simultaneously. While traditional ELISA systems require a high number of enzyme labels to generate reader-detectable signals, SIMOA utilizes femtoliter-sized reaction chambers that can isolate and detect single enzyme molecules. In humans, plasma Aβ oligomer concentrations measured with SIMOA decrease several years before a clinical diagnosis of AD [19]. In addition, low plasma concentrations of Aβ42 combined with high plasma concentrations of neurofilament light chain (NfL) are associated with all-cause and AD dementia [19]. These findings confirm that both biomarkers can be used as minimally-invasive tools to predict AD onset in non-AD population. We have recently shown that plasma NfL can be successfully measured in a population of pet dogs with single molecule array assay technology (SIMOA) [20]. In this study, we have used the same SIMOA technology to explore plasma concentrations of the amyloid oligomers, amyloid-β42 (Aβ42) and amyloid-β40 (Aβ40) in healthy dogs at different life-stages and in elderly dogs affected with CDS. In addition, we evaluated the dynamics of the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio. Our findings confirmed that plasma concentrations of Aβ42 and Aβ40 can be successfully measured using SIMOA in pet dogs and that their concentrations increase with age and decrease with the presence of CDS. Our data mirrors recent human literature and suggests that future, large-cohort studies assessing plasma Aβ with SIMOA may provide an important means of monitoring disease state and response to therapy, enhancing the translational potential of this naturally occurring model.

METHODS

Animals

This study included 47 dogs recruited from the staff of the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine. There were 36 healthy dogs and 11 suffering from CDS. Dogs were stratified using life stage categories based on the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) canine life stage guidelines [21] combined with breed lifespan by American Kennel Club (AKC). Inclusion criteria included a normal physical examination, normal vision, intact hearing and the ability to walk independently. Dogs were excluded if they had focal neurological deficits on neurological examination indicating an underlying neurological condition distinct from age related dementia, if they had an active neurological condition such as epilepsy that could alter plasma biomarker concentrations, or if they were being treated with behavior modifying medications such as serotonin antagonists/reuptake inhibitors.

All dogs underwent physical, orthopedic and neurological examinations followed by a blood draw. Cognitive status was established using the Canine Dementia Scale (CADES (Fig 1) [22]. This scale is completed by owners and assigns a score based on owner assessment of 17 items, grouped into spatial orientation, social interactions, sleep-wake cycles and house soiling. Cognitive impairment was then classified for each dog as normal, mild, moderate or severe. All owners were provided with details of the study, were given the opportunity to ask questions, and signed an informed consent. All procedures were performed in accordance with the North Carolina State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Data gathered on the dogs included age, breed, sex and health status. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical information for participants grouped according to life stage and disease status.

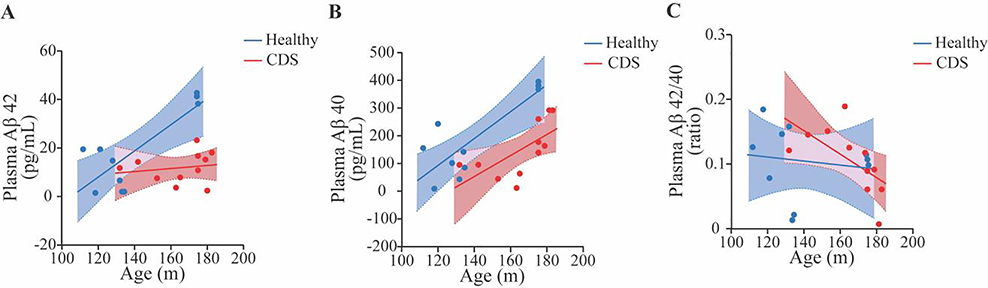

Fig. 1. Plasma amyloid beta 42 (Aβ42) and amyloid beta 40 (Aβ40) concentrations increases with age in the population of healthy pet dogs (A and B). The ratio of Aβ42/40 decreases with age in the same population (C).

A multiple linear regression model was fitted using plasma Aβ42, Aβ40 and Aβ42/40 concentrations as response variable and age, sex and body weight as dependent variables. There was a positive correlation between age and plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40, (r2 =0.27, p=0.001) and (r2 =0.42, p<0.001 ), respectively. There was a negative correlation between age and ratio of Aβ42/40 (r2=0.15, p=0.02).

Table 1. Demographic features of study participants.

Mean (SD) have been used to present plasma concentrations of Aβ42, Aβ40 and ratio of Aβ42/40.

| Number of dogs (n) | Life Stage (AAHA) | Age (years) | Dementia Score (CADES) | Plasma Aβ42 (pg/mL) (Mean SD) | Plasma Aβ40 (pg/mL) (Mean SD) | Plasma Aβ42/40 (pg/mL) (Mean SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Controls | n =12 | puppy/junior | 0.40–2 | Normal | 1.23±0.95 | 38.29±49.43 | 0.19±0.15 |

| n =14 | adult/mature | 2.1– 9 | Normal | 10.99±5.45 | 131.05±80.17 | 0.11±0.03 | |

| n =10 | senior/geriatric | 9.3–14.5 | Normal | 18.65±16.65 | 192.88±146.38 | 0.10±0.05 | |

| Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome (CDS) | n = 11 | senior/geriatric | 11.0–15.6 | Mild, n=4 | 13.78±8.85 | 198.51±94.52 | 0.08±0.05 |

| Moderate, n=2 | 11.34 & 7.19 | 94.26 & 47.84 | 0.12 & 0.15 | ||||

| Severe, n=5 | 10.87±5.78 | 143.26±107.76 | 0.10±0.05 |

Acronyms: CDS – Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome; AAHA – American Animal Hospital Association; CADES – Canine Dementia Scale; plasma Aβ42-amyloid beta 42; plasma Aβ40-amyloid beta 40; plasma Aβ42/40 – ratio of Aβ42 and Aβ40; SD - standard deviation.

Measurement of plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40 concentrations

Blood samples were taken into EDTA tubes and centrifuged at 2000 × g at 4 °C for 8 min within 2 h of collection. Plasma supernatant was collected, divided into aliquots, and frozen at − 80 °C until further use. Samples were thawed on ice before analysis and the concentration of plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40 was measured using Single Molecule Array Assay kit (AB40 and AB42, Quanterix, Lexington, MA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Intra-assay coefficient of variation has been described to vary between 0.1% and 8%, and inter-assay coefficient of variation between 2% and 8%. The limit of detection for Aβ42 assay was 0.034 pg/mL (range 0.014–0.052 pg/mL) and for Aβ40 assay was 0.17 pg/ml (range 0.092–0.28 pg/ml).

Statistical Analysis

Summary data were prepared on age, weight, sex, breed, CADES score and Aβ42, Aβ40 and Aβ42/40 ratio with dogs grouped according to life stage. In the first analysis, the relationship between age, weight and sex on Aβ42, Aβ40 and Aβ42/40 was examined in healthy dogs using linear regression. Plasma Aβ42, Aβ40 and ratio of Aβ42/40 concentration were compared between the life stage groups of healthy dogs using the Wilcoxon test for each pair. The relationship between CDS and plasma Aβ42, Aβ40 and ratio of Aβ42/40 concentrations was examined in two different ways. Firstly, a model was built to examine the effect of disease status (healthy versus CDS) on plasma Aβ42, Aβ40 and Aβ42/40 concentration with age as a covariate. Finally, logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between CADES score and Aβ42, Aβ40 and Aβ42/40 concentrations in senior/geriatric dogs only, both with and without CDS. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP14 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All reported p values were considered to be statistically significant at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p< 0.001 and p<0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics

Forty-seven pet dogs (26 males and 21 females) of various breeds (Beagle n=8, Boxer n=3, Border Collie n=4, Cairn Terrier n=2, German Shepherd Dog n=3, Golden Retriever n=1, Hound n=1, Jack Russell Terrier n=2, Labrador Retriever n=7, Mix Breed n=12, Pembroke Welsh Corgi n=2, Rottweiler n=2) were enrolled in this study. Of these, 36 were healthy and 11 were diagnosed with CDS. The ages of dogs ranged from 0.40–15.6 years. The population of healthy pet dogs included puppy/junior dogs (0.40– 2 years, n=12), adult/mature dogs (2.1– 9 years, n=14) senior/geriatric dogs (9.3–14.5 years, n=10). All dogs with CDS were senior/geriatric (11.0–15.6 years). Demographic features of study participants and CADES dementia scores are presented in Table1.

Plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40 concentrations in 36 healthy pet dogs increase with age

Plasma concentrations of Aβ42, Aβ40 and the Aβ42/β40 ratio is shown in Table 1. Plasma Aβ42 concentrations increased with age (r2 =0.27, p=0.001) (Fig. 1A) and were not affected by body weight (r2=0.038, p=0.25) and/or sex (r2 = 0.14, p=0.07). Similarly, plasma Aβ40 concentrations increased with age (r2 =0.42, p<0.001) (Fig. 1B) and were not affected by body weight (r2 =0.05, p=0.17) and/or sex (r2 =0.16, p=0.055). The ratio of Aβ42/β40 decreased with age (r2=0.15, p=0.02) and was not affected by body weight (r2= 0.02, p=0.41) nor sex (r2=0.01, p=0.49) in the population of healthy pet dogs (Fig. 1C). With dogs grouped according to life stage, the plasma concentrations of both peptides were significantly different between each group as illustrated in Fig 2. Both Aβ42 and Aβ40 increase in concentration with increasing maturity of life stage, while there was a decrease in the Aβ42/β40 ratio.

Fig. 2. Plasma amyloid beta 42 (Aβ42) and amyloid beta 40 (Aβ40) concentrations increased in an age-dependent manner in the population of healthy pet dogs stratified into different life stage groups (A and B). The ratio of amyloid beta 42/amyloid beta 40 (Aβ42/40) decreased with age (C) between life-stage group.

P/J: puppy/junior (n=12); A/M: adult/mature (n=14); S/G: senior/geriatric (n=10). There were statistically significant differences between the groups and when each group was compared pairwise with the Wilcoxon Test: (A) P/J vs A/M (p<0.0001), P/J vs S/G (p=0.006), A/M vs S/G (p=0.006); (B) P/J vs A/M (p<0.0001), P/J vs S/G (p =0.002), A/M vs S/G (p =0.002); (C) P/J vs A/M (p<0.0001), P/J vs S/G (p=0.0002), A/M vs S/G (p=0.0002). (p < 0.01*, p< 0.001** and p<0.0001***).

Plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40 concentrations are lower in dogs with CDS and correlate negatively with CADES score

Plasma concentrations of Aβ42, Aβ40 and the Aβ42/β40 ratio in dogs with CDS are shown in Table 1. When concentrations of Aβ42 and Aβ40 were compared between 11 dogs affected with CDS and 10 healthy senior/geriatric dogs using multivariate analysis with age as a covariate. Dogs with CDS exhibited lower concentrations of Aβ42 and Aβ40 than healthy dogs (r2= 0.46, p=0.0048 and r2= 0.61, p=0.001, respectively) (Fig. 3A and 3B). The ratio of Aβ42/β40 did not significantly differ between the CDS and healthy senior/geriatric group, (r2 =0.1, p=0.4) (Fig. 3C). A negative correlation was found between plasma concentrations of Aβ42, Aβ40 and CADES scores in senior and geriatric dogs (including dogs with CDS) (r2=0.34, p=0.02) and (r2=0.59, p=0.002), respectively (Fig. 4A and 4B) but there was no relationship between the plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and CADES score (r2=0.12, p=0.3) (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 3. The relationship between age and plasma amyloid-beta 42 (Aβ42) (A), amyloid-beta 40 (Aβ40) (B), and ratio of amyloid-beta 42 and amyloid-beta 40 (Aβ42/40) (C) concentration in a population of healthy senior/geriatric dogs (n=10) and senior/geriatric dogs affected with CDS (n=11).

There was a significant difference between these groups for Aβ42 and Aβ40 when evaluated using logistic regression: (A) (r2 =0.46, p=0.0048); (B) (r2 =0.61, p=0.001). Analysis of Aβ42/40 ratio did not show significance (C) (r2 =0.1, p=0.4).

Fig. 4. The relationship between plasma amyloid beta 42 (Aβ42), amyloid beta 40 (Aβ40) and ratio of amyloid beta 42/amyloid beta 40 (Aβ42/40) concentration and Canine Dementia Score (CADES) in healthy senior/geriatric dogs (n=10) and senior/geriatric dogs with CCD (n=11).

Plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40 concentrations are associated with the CADES score when evaluated using logistic regression: (A) Aβ42 (r2=0.34, p=0.02); Aβ40 (r2=0.59, p=002). The ratio of Aβ42/40 did not significantly correlate with CADES score (r2=0.12, p=0.3).

DISCUSSION

In this study we report that in healthy pet dogs, plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40 concentrations increase in an age-dependent manner and are not affected by body weight or sex. In addition, we show that CDS-affected pet dogs have reduced plasma concentrations of Aβ42 and Aβ40, when compared to cognitively intact, life-stage matched healthy individuals. The ratio of Aβ42/β40 decreased with age in a healthy population of pet dogs, however no statistically significant difference was noted between CDS-affected and healthy senior/geriatric study participants.

Both humans and dogs suffer from similar age-related neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD and CDS [1]. Importantly, both diseases occur spontaneously and both species are exposed to the same environmental conditions and potential neurotoxins [23]. Both also share several neuropathological hallmarks including extracellular deposition of amyloid beta plaques, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, frontal and temporal cortical atrophy and neuro-axonal loss [5]. Intracellular accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein has been also observed across both species, but the formulation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) composed of this protein has long been recognized as a human-specific feature [24–26]. Recently, it has been shown that dogs affected with CDS share 99% sequence homology for tau microtubular binding domains (MBD) and that they can develop argyrophilic tau fibrillary tangles within cortex and hippocampus [27, 28].

Numerous studies have been performed to identify relevant plasma biomarkers in humans with AD, however, the number of studies in CDS affected pet dogs is limited [29]. The identification of clinically relevant, non-invasive plasma biomarkers for CDS would not only supplement current veterinary knowledge, but also facilitate bi-directional flow of translational research between the two species. Amyloid beta peptides are the products of enzymatic cleavage of amyloid precursor protein performed by β and γ-secretases as well as β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 [30]. The 42 amino-acid isoform of Aβ peptide is the most commonly found insoluble deposit in AD and CDS affected brains [31, 32]. Several previous studies have indicated that CSF concentration of Aβ42 decreases in humans with AD and in dogs with CDS and that decreased concentrations inversely correlate with amyloid beta depositions within the brain parenchyma [13–15]. The concentration of CSF amyloid beta 40 (Aβ40) has been also evaluated in both species; however its correlation with the presence of AD dementia is less clear [33]. By contrast, several human studies reported that the ratio of Aβ42/40 had higher diagnostic potential than Aβ42 alone [34]. A number of positive emission tomography (PET) - based studies using different Aβ PET tracers have been performed in both dogs and humans and revealed correlations between Aβ42 in CSF and amyloid PET [35, 36]. Using PET imaging, the concentration of Aβ42 in CSF Aβ42 decreases before parenchymal amyloid beta is detectable within the brain suggesting that it is more sensitive marker in the early stages of AD [37].

The CSF contains molecules of great diagnostic and prognostic value, but sampling CSF is invasive and in dogs requires general anesthesia. Unfortunately, only a fraction of molecules detected in the CSF reach the vascular system [38] but high sensitivity technologies have enabled their measurement in peripheral blood, significantly advancing the neurodegenerative field. To date there have been two contradictory studies that assessed plasma concentrations of Aβ42 and Aβ40 in healthy dogs and dogs with CDS. Both studies used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to establish plasma concentrations and both included different approaches to perform cognitive status evaluation [21, 39]. A study by Gonzalez-Martinez et. al [39] was performed on a cohort of eighty-eight pet dogs stratified into different age categories. The age of dogs classified as ‘young’ ranged between one to four years, for ‘middle age’ between five to eight years and for ‘old unimpaired’ and ‘old impaired’ was greater than or equal to nine years. All dogs recruited into the study were small to medium size. This study found that younger dogs had higher plasma Aβ42 and Aβ40 concentrations than healthy aged dogs and that dogs suffering from only mild cognitive impairment had high concentrations of Aβ42 and a high Aβ42/40 ratio. Dogs diagnosed with severe cognitive impairment exhibited comparable values to control individuals. Plasma Aβ40 did not correlate with presence nor severity of CDS. It is notable that although the concentration of plasma Aβ40 was higher than Aβ42, both were within the same level of magnitude. Similar to our study, the majority of human studies report plasma concentrations for Aβ40 10–20 times higher than Aβ42 within the same individuals. The study by Schutt et. al [23] included fifteen pet dogs of different breeds and age (between nine to fifteen years old) and evaluated the correlation between plasma concentrations and brain deposition of amyloid beta via immunohistochemistry and ELISA. Specific plasma concentrations were not reported; however, plasma Aβ42 concentration correlated with maturation stage of Aβ plaques. No significant correlations existed between plasma Aβ42 and cognitive status or with soluble or insoluble fractions of Aβ42 quantified within prefrontal cortex. It is unclear why these studies’ findings differed from ours, but possible reasons include the differing canine populations, Aβ42 and 40 assays and means of evaluating cognitive status. Our study used the CADES scale to establish cognitive status, while these studies used either the Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Rating scale (CCDR) [40], which appears to be less sensitive to mild cognitive impairment than the CADES scale[20], or a set of scales which have not been compared directly with the CADES scale [9].

In the current study, we used the SIMOA assay to measure plasma concentrations of Aβ42 and Aβ40 and established the level of dementia using the validated CADES scale. By stratifying dogs into different life-stages, we were able to account for breed related differences in longevity and to correlate the life stages to human life stages.

Our study had some limitations, including a relatively low number of dogs affected with CDS. It was a cross-sectional rather than a longitudinal study, and longitudinal data would add greatly to the strength of observations made. Dogs were diagnosed with CDS based on physical and neurological examination to exclude metabolic and focal neurologic processes, as well as consistent history. The addition of brain MRI and CSF analysis and ultimately necropsy confirmation would enhance the study.

Our findings that plasma amyloid beta concentrations increase in an age-dependent manner in a population of healthy individuals and decrease with the presence of CDS mirror findings in humans. Importantly, our results provide a strong rationale for large scale studies in companion dogs which may contribute to acceleration of current translational progress in AD studies.

Supplementary Material

Suppl. Fig 1. The CADES score used to classify dogs as normal (0-7), mild (8-23), moderate (24-44) or severe (45-95) cognitive dysfunction. Seventeen items, distributed into four domains associated with behavioral changes (spatial orientation, social interactions, sleep-wake cycles and house soiling) were assessed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Quanterix company representatives for technical support. We want to thank dogs and their owners for taking part in the study.

Funding Information

This work is supported by the Dr. Kady M Gjessing and Rhanna M Davidson Distinguished Chair of Gerontology. F.M.M. is funded by NIH/NEI K08 EY028628.

Footnotes

Declarations: We declare that the content of our research article is original, has not been published or accepted for publication and is not currently under consideration for publication elsewhere. We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References:

- 1.Prpar Mihevc S and Majdic G, Canine Cognitive Dysfunction and Alzheimer’s Disease - Two Facets of the Same Disease? Front Neurosci, 2019. 13: p. 604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallis LJ, et al. , Demographic Change Across the Lifespan of Pet Dogs and Their Impact on Health Status. Front Vet Sci, 2018. 5: p. 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapagain D, et al. , Cognitive Aging in Dogs. Gerontology, 2018. 64(2): p. 165–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Head E, A canine model of human aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2013. 1832(9): p. 1384–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewey CW, et al. , Canine Cognitive Dysfunction: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract, 2019. 49(3): p. 477–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnstone EM, et al. , Conservation of the sequence of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid peptide in dog, polar bear and five other mammals by cross-species polymerase chain reaction analysis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 1991. 10(4): p. 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Head E, et al. , Visual-discrimination learning ability and beta-amyloid accumulation in the dog. Neurobiol Aging, 1998. 19(5): p. 415–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rofina JE, et al. , Cognitive disturbances in old dogs suffering from the canine counterpart of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res, 2006. 1069(1): p. 216–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colle MA, et al. , Vascular and parenchymal Abeta deposition in the aging dog: correlation with behavior. Neurobiol Aging, 2000. 21(5): p. 695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cummings BJ, et al. , Beta-amyloid accumulation correlates with cognitive dysfunction in the aged canine. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 1996. 66(1): p. 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mormino EC and Papp KV, Amyloid Accumulation and Cognitive Decline in Clinically Normal Older Individuals: Implications for Aging and Early Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis, 2018. 64(s1): p. S633–S646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewczuk P, et al. , Cerebrospinal Fluid Abeta42/40 Corresponds Better than Abeta42 to Amyloid PET in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis, 2017. 55(2): p. 813–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagan AM, et al. , Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann Neurol, 2006. 59(3): p. 512–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Head E, et al. , Amyloid-beta peptide and oligomers in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of aged canines. J Alzheimers Dis, 2010. 20(2): p. 637–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borghys H, et al. , Young to Middle-Aged Dogs with High Amyloid-beta Levels in Cerebrospinal Fluid are Impaired on Learning in Standard Cognition tests. J Alzheimers Dis, 2017. 56(2): p. 763–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Bryant SE, et al. , Blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer disease: Current state of the science and a novel collaborative paradigm for advancing from discovery to clinic. Alzheimers Dement, 2017. 13(1): p. 45–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D and Mielke MM, An Update on Blood-Based Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease Using the SiMoA Platform. Neurol Ther, 2019. 8(Suppl 2): p. 73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Wolf F, et al. , Plasma tau, neurofilament light chain and amyloid-beta levels and risk of dementia; a population-based cohort study. Brain, 2020. 143(4): p. 1220–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panek WK, et al. , Plasma Neurofilament Light Chain as a Translational Biomarker of Aging and Neurodegeneration in Dogs. Mol Neurobiol, 2020. 57(7): p. 3143–3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartges J, et al. , AAHA canine life stage guidelines. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc, 2012. 48(1): p. 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aladar Madari JF, Stanislav Katina, Tomas Smolekc, Petr Novakc, and M.N. Tatiana Weissovaa, Norbert Zilka, Assessment of severity and progression of canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome using the CAnine DEmentia Scale (CADES). Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 2015. 171: p. 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schutt T, et al. , Dogs with Cognitive Dysfunction as a Spontaneous Model for Early Alzheimer’s Disease: A Translational Study of Neuropathological and Inflammatory Markers. J Alzheimers Dis, 2016. 52(2): p. 433–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pugliese M, et al. , Diffuse beta-amyloid plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau are unrelated processes in aged dogs with behavioral deficits. Acta Neuropathol, 2006. 112(2): p. 175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iqbal K, et al. , Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res, 2010. 7(8): p. 656–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu CH, et al. , Histopathological and immunohistochemical comparison of the brain of human patients with Alzheimer’s disease and the brain of aged dogs with cognitive dysfunction. J Comp Pathol, 2011. 145(1): p. 45–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kontsekova E, et al. , First-in-man tau vaccine targeting structural determinants essential for pathological tau-tau interaction reduces tau oligomerisation and neurofibrillary degeneration in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Alzheimers Res Ther, 2014. 6(4): p. 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smolek T, et al. , Tau hyperphosphorylation in synaptosomes and neuroinflammation are associated with canine cognitive impairment. J Comp Neurol, 2016. 524(4): p. 874–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thambisetty M and Lovestone S, Blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: challenging but feasible. Biomark Med, 2010. 4(1): p. 65–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chow VW, et al. , An overview of APP processing enzymes and products. Neuromolecular Med, 2010. 12(1): p. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selkoe DJ, Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev, 2001. 81(2): p. 741–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Head E, et al. , Region-specific age at onset of beta-amyloid in dogs. Neurobiol Aging, 2000. 21(1): p. 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoji M, et al. , Combination assay of CSF tau, A beta 1–40 and A beta 1–42(43) as a biochemical marker of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci, 1998. 158(2): p. 134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewczuk P, et al. , Neurochemical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia by CSF Abeta42, Abeta42/Abeta40 ratio and total tau. Neurobiol Aging, 2004. 25(3): p. 273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller EG, et al. , Amyloid-beta PET-Correlation with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and prediction of Alzheimer s disease diagnosis in a memory clinic. PLoS One, 2019. 14(8): p. e0221365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yun T, et al. , Temporal and anatomical distribution of (18)F-flutemetamol uptake in canine brain using positron emission tomography. BMC Vet Res, 2020. 16(1): p. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchhave P, et al. , Cerebrospinal fluid levels of beta-amyloid 1–42, but not of tau, are fully changed already 5 to 10 years before the onset of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2012. 69(1): p. 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strazielle N and Ghersi-Egea JF, Potential Pathways for CNS Drug Delivery Across the Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier. Curr Pharm Des, 2016. 22(35): p. 5463–5476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez-Martinez A, et al. , Plasma beta-amyloid peptides in canine aging and cognitive dysfunction as a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol, 2011. 46(7): p. 590–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salvin HE, et al. , The canine cognitive dysfunction rating scale (CCDR): a data-driven and ecologically relevant assessment tool. Vet J, 2011. 188(3): p. 331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Suppl. Fig 1. The CADES score used to classify dogs as normal (0-7), mild (8-23), moderate (24-44) or severe (45-95) cognitive dysfunction. Seventeen items, distributed into four domains associated with behavioral changes (spatial orientation, social interactions, sleep-wake cycles and house soiling) were assessed.