Abstract

Background:

The association of community factors and outcomes after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) has not been comprehensively described. We evaluated the impact of community health status on allogeneic HCT outcomes using the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps (CHRR) and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR).

Methods:

We included 18,544 adult allogeneic HCT recipients reported to CIBMTR by 170 United States centers in 2014–2016. We derived sociodemographic, environmental, and community indicators from the CHRR, created an aggregate community risk score, and assigned them to each patient (PCS) and transplant center (CCS). Higher scores indicate less healthy communities. We studied the impact of PCS and CCS on patient outcomes after allogeneic HCT.

Results:

The median age was 55 (range 18–83). The median PCS was −0.21 (range, −1.37 to 2.10; standard deviation [SD] 0.42) and the median CCS was −0.13 (range −1.04 to 0.96; SD 0.40). In multivariable analyses, higher PCS was associated with inferior survival (hazard ratio [HR]/ 1 SD increase 1.04, [99% CI 1.00–1.08], p=0.0089). Among hematologic malignancies, we observed a tendency towards inferior survival (HR 1.04, [1.00–1.08], p=0.0102) with higher PCS; higher PCS was associated with higher non-relapse mortality (NRM) (HR 1.08, [1.02–1.15], p=0.0004). CCS was not significantly associated with survival, relapse, or NRM.

Conclusion:

Patients residing in counties with worse community health status have inferior survival, as a result of an increased risk of NRM after allogeneic HCT. There was no association between community health status of transplant center location and allogeneic HCT outcomes.

Keywords: Hematopoietic cell transplantation, Allogeneic transplant, Community health, Survival

Precis:

We developed a new community risk score for HCT recipients derived from a large publicly available database (the County Health Rankings & Roadmaps) to describe patient and transplant center community health status. Patient community-risk score (PCS) was associated with non-relapse mortality and overall survival, however center community-risk score (CCS) was not associated with transplant outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) access and outcomes can be influenced by several factors contributing to health care disparity.1–6 Health care disparity is a complex construct; multilevel patient, provider, institutional, community, and societal factors are important in the context of allogeneic HCT.2,3 These factors may influence patients’ choices and behaviors as well as transplant center practices. The role of patient-level factors is easier to understand and evaluate; age, sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status have been frequently studied as social determinants of HCT access and recipient outcomes.1–4 The impact of health-disparities as determined by community factors on allogeneic HCT outcomes is less clear and has been only partially described with sociodemographic factors such as race, ethnicity, and income. Community factors may be associated with allogeneic HCT outcomes since transplant centers and providers cannot always identify, address, or mitigate patient-specific community and social issues that may directly or indirectly influence recipient outcomes. Additionally, the health status of the community where a center is located may affect its practices, referral patterns, and care delivery system, which may ultimately be reflected in individual patient outcomes and the aggregate outcomes of all patients transplanted at that center.

As noted above, the literature in HCT has mostly focused on sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.7,8 A significant challenge in comprehensively describing the myriads of healthcare disparity factors in allogeneic HCT was the lack of a tool that can objectively evaluate community and social determinants of health among transplant recipients. The County Health Rankings and Roadmaps (CHRR) project uses the information on sociodemographic, environmental, and community health status from several national data resources and summarizes them into a composite measure of the health status for all counties in the United States (US).9 County health status using this resource has been associated with access and outcomes in complex surgical procedures and has been investigated in solid organ transplantation.10–12

We used data on community health disparity factors from the CHRR and on patient characteristics and transplant outcomes from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) to test our hypothesis that community health status of the patient and the center are associated with patient outcomes after allogeneic HCT. The primary objective of our study was to evaluate associations of community health status of patient residence and community health status of transplant center location with patient survival, relapse, and non-relapse mortality (NRM).

The CIBMTR administers the Stem Cell Therapeutic Outcomes Database, a component of the C.W. Bill Young Transplantation Program, through a contract with the Health Resources and Services Administration. Under the purview of this law, transplant centers in the US are required to report data for all allogeneic HCT recipients to the CIBMTR. As part of this contract, the CIBMTR performs an annual center-specific outcomes analysis (CSA) and reports risk-adjusted one-year survival for first allogeneic HCT of rolling three-year window for each center in the US.13–15 CSA method reflects recommendations of the 2010 Center-Specific Outcomes Analysis Forum.16,17 The center-specific outcomes analysis model is a complex statistical model, currently considering over 30 variables. Variables to be adjusted for are determined through model selection procedures. As a secondary objective, we explored whether patient community-risk score (PCS) and center community-risk score (CCS) would be independent predictors of 1-year survival, using the same exact model (pseudo-value logistic regression model) and parameters that are currently analyzed in the CSA model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source: CIBMTR

The CIBMTR is a voluntary and international working group of transplantation centers that contribute data on their HCT to statistical centers located at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee and the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP), Minneapolis. Participating centers are required to report all transplantations consecutively; patients are followed longitudinally. Computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with the Privacy Rule (HIPAA) as a Public Health Authority and with all applicable federal regulations, as determined by continuous review of the Institutional Review Board of the NMDP.

Data Source: CHRR

The CHRR project is a collaboration between the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The CHRR provides annually updated information on county-level health factors and outcomes that can serve as surrogate measures of disparities among communities.9,18 Data on these measures are obtained from a variety of public data sources.18 The measures are standardized among all counties across the US, combined using scientifically-informed weights and are publicly available at www.countyhealthrankings.org. Details of the ranking methodology and measures are available through the CHRR website. Briefly, counties in each of the 50 US states are ranked according to summaries of a variety of health measures. The overall “Health Factors” summary score is a weighted composite of four components: health behaviors, clinical care, social and economic environment, and physical environment. For example, the measures included within the health behaviors domain are rates of adult smoking, adult obesity, food environment index, physical inactivity, access to exercise opportunities, excessive drinking, alcohol-impaired driving deaths, sexually transmitted diseases, and teen birth. The clinical care domain consists of rates of uninsured, preventable hospital stays, diabetes monitoring, mammography screening, and availability of primary care physicians, dentists, and mental health providers.

Using the 2018 CHRR data, we created patient- and center-specific composite scores based on “Health Factors” assigned to the ZIP code of patient residence and center location, allowing calculation of a nationally standardized score for each patient and center, respectively. The Z-scores of thirty variables that constitute “Health Factors” from the CHRR were normalized to bring all measures into the same scale by subtracting the national average of that measure and dividing by the national standard deviation (SD). For most measures, a higher score indicated worse health factors. For the few measures where this was reversed (i.e., diabetes monitoring and mammography screening), the Z-scores were multiplied by −1 to maintain directional consistency. The final PCS was computed by multiplying Z-scores for all measures by their weights and then adding all weighted measures. For PCS, we linked ZIP codes of patient residence at the time of HCT to county information, using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS).19 Similarly, we assigned CCS by deriving a composite score from ZIP code and FIPS of each transplant center location.

Study Population

For our study, we used data on patients included in the CIBMTR’s 2018 center-specific outcomes analysis dataset. The dataset included 24,141 adult recipients who underwent their first allogeneic HCTs at US centers from 2014 to 2016. We excluded recipients who were <18 years of age at the time of HCT due to the concern that different factors influence their outcomes compared to adults (N=3,784). We excluded patients who had missing ZIP code or FIPS (N=506) or had not consented for research (N=1,166). We also excluded 138 patients residing in counties for whom no data were available in the CHRR. Categories with a very small number of recipients were also excluded (2 with inherited erythrocyte abnormalities and one related cord blood transplant recipient). Hence, our final study cohort consisted of 18,544 patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | All diagnoses N (%) | Hematologic malignancies N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 18,544 | 17,793 |

| Number of transplant centers | 170 | 167 |

| Male | 10,707 (58) | 10,290 (58) |

| Age, median (years, range) | 55 (18–83) | 56 (18–83) |

| Recipient race | ||

| White | 15,732 (85) | 15,205 (85) |

| Black/African American | 1,398 (8) | 1,250 (7) |

| Asian | 721 (4) | 685 (4) |

| Others/ Unknown | 696 (3) | 653 (4) |

| Karnofsky Score at transplant, 70–100 | 17,961 (97) | 17,253 (97) |

| Positive recipient CMV status | 11,790 (64) | 11,295 (63) |

| Sorror HCT-Comorbidity Index14† | ||

| 0 | 3,750 (20) | 3,575 (20) |

| 1–2 | 5,535 (30) | 5,343 (30) |

| 3–4 | 5,936 (32) | 5,692 (32) |

| ≥5 | 3,325 (18) | 3,183 (18) |

| Estimated household income in USD, median (range) | 57,573 (7,500->200,000) | 57,640 (7,500->200,000) |

| Disease indication and status for HCT | ||

| Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (AML) | 7,471 (40) | 7,471 (42) |

| CR-1 | 4,724 | 4,724 |

| CR-2 | 1,148 | 1,148 |

| CR-3+ or relapse/ refractory | 1,599 | 1,599 |

| Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) | 2,492 (13) | 2,491 (14) |

| CR-1 | 1,723 | 1,723 |

| CR-2 | 482 | 482 |

| CR-3+ or relapse/ refractory | 286 | 286 |

| Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia | 609 (3) | 609 (3) |

| Early | 75 | 75 |

| Intermediate | 264 | 264 |

| Advanced | 240 | 240 |

| Very advanced | 30 | 30 |

| Other acute leukemia | 212 (1) | 212 (1) |

| Other chronic leukemia | 389 (2) | 389 (2) |

| CR or PR | 298 | 298 |

| Stable disease | 57 | 57 |

| Progression/ relapse | 34 | 34 |

| Myelodysplastic Syndrome | 3,086 (17) | 3,086 (17) |

| Myeloproliferative Diseases | 723 (4) | 723 (4) |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 1,892 (10) | 1,892 (11) |

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 382 (2) | 382 (2) |

| Plasma Cell Disorders | 538 (3) | 538 (3) |

| Other Malignancy (Solid Tumors) | 19 (<1) | -- |

| Total nonmalignant diseases | 735 (4) | -- |

| Product type | ||

| BM | 2,808 (15) | 2,295 (13) |

| PBSC | 14,549 (78) | 14,335 (81) |

| PBSC + BM | 16 (<1) | 15 (<1) |

| Cord blood ± Others | 1,174 (6) | 1,148 (6) |

| Donor type | ||

| Unrelated donor | 10,685 (58) | 10,318 (58) |

| Matched sibling | 5,417 (29) | 5,166 (29) |

| Greater than one locus mismatched relative | 1,945 (10) | 1,841 (10) |

| Other | 500 (3) | 468 (3) |

| Unrelated BM or PBSC donor human leukocyte antigen match | ||

| 8/8 | 7,734 (81) | 7,462 (81) |

| 7/8 | 1,282 (13) | 1,234 (13) |

| ≤ 6/8 or not specified | 496 (6) | 474 (3) |

| Age of unrelated BM or PBSC donor, median (years, range) | 28 (18–64) | 28 (18–64) |

| BM or PBSC donor/recipient sex match | ||

| Male-male | 6,722 (39) | 6,454 (39) |

| Male-female | 4,259 (25) | 4,075 (24) |

| Female-male | 3,361 (19) | 3,228 (19) |

| Female-female | 3,000 (17) | 2,859 (17) |

| Unknown | 31 (<1) | 29 (<1) |

| Unrelated BM or PBSC donor age at transplant, years | ||

| Under 30 | 5,641 (59) | 5,435 (59) |

| 30 to 39 | 2,214 (23) | 2,139 (23) |

| 40 to 49 | 1148 (12) | 1,102 (12) |

| 50 and above | 446 (5) | 434 (5) |

| Unknown | 63 (<1) | 60 (1) |

| Unrelated BM or PBSC donor ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 535 (6) | 505 (6) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 4,314 (45) | 4,153 (45) |

| Unknown | 4,663 (49) | 4,512 (49) |

| Unrelated BM or PBSC donor race | ||

| White | 5,242 (55) | 5,045 (55) |

| Black/African American | 212 (2) | 193 (2) |

| Asian | 175 (2) | 164 (2) |

| Others/ Unknown | 3,883 (41) | 3,768 (21) |

| Positive Donor CMV status among BM or PBSC grafts | 7,903 (45) | 7,547 (45) |

| History of parity among BM or PBSC donor | 2,209 (13) | 2,123 (13) |

| Year of transplant | ||

| 2014 | 6,062 (33) | 5,835 (33) |

| 2015 | 6,213 (33) | 5,937 (33) |

| 2016 | 6,272 (34) | 6,021 (34) |

| Prior autologous stem cell transplant | 1,683 (9) | 1,675 (9) |

| Median follow-up of survivors, months (range) | 24 (1.5–51.8) | 24 (1.5–51.8) |

1 case with unknown HCT-comorbidity index at the time of transplantation

Abbreviations: ALL = Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia; AML = Acute Myelogenous Leukemia; BM = Bone Marrow; CB = Cord Blood; CMV = Cytomegalovirus; CR= complete remission; HCT = Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation; PBSC = Peripheral blood Stem Cells; PR= partial remission.

The main objective of our study was to evaluate the association of PCS and CCS with patient survival after allogeneic HCT. Since we were also interested in assessing the association between PCS and CCS with relapse and NRM, we conducted a subgroup analysis in patients with hematologic malignancies (N=17,793) after excluding 735 patients with nonmalignant diseases and 19 with solid tumors (Table 1).

For our secondary objective, we explored whether patient- and center-level health disparity factors would have a significant contribution to the center-specific analysis focused on 1-year survival. We included our study cohort of 18,544 patients to test whether the addition of PCS or CCS provided any additional information on center-specific survival that is estimated by a validated methodology. For this analysis, we used the exact same model, parameters, and outcome currently used in the CSA model.

Statistical Analysis

For the primary objective, we used a Cox proportional hazards model to test the association of PCS and CCS with OS, relapse, and NRM. For relapse and NRM analysis, the cohort was further restricted to those with hematologic malignancies (N=17,793). Variables included for the analyses were: recipient age/sex, recipient race/ethnicity, donor age/sex, donor race/ethnicity, performance score at HCT, disease indication, HCT comorbidity index,20 transplant year, recipient and donor cytomegalovirus status, graft sources, donor types, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match status, donor parity, history of mechanical ventilation, history of invasive fungal infection, socioeconomic status, disease-specific variables (e.g., time from diagnosis to transplant for acute myeloid leukemia [AML] and acute lymphoblastic leukemia [ALL], therapy related AML or myelodysplastic syndrome [MDS], AML European Leukemia Network risk group,21 ALL cytogenetic risk group,22 cell lineage for ALL, MDS risk score,23 chemotherapy sensitivity for lymphomas, subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, cytogenetic risk group,24 and International Staging System score for myeloma). Conditioning intensity was additionally considered as a covariate.25 Given the very large sample size, we used the alpha level of 0.01 as a significance level for this analysis.

For our secondary exploratory analysis, we evaluated whether PCS and CCS provide any additional information on the endpoint used in the annual center-specific analysis of one-year survival. We examined if the addition of PCS and CCS in regression models was significantly associated with the adjusted odds of one-year survival; the center-specific analysis uses a pseudo-value logistic regression model which allows to accommodate censoring. CSA uses an alpha level of 0.05 to declare significance; thus, the same threshold was used for this analysis.13 As noted above, we included all adult recipients with all disease indications in this analysis (n=18,544).

All analyses were done using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). All tests were two-sided.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Distribution of PCS and CCS

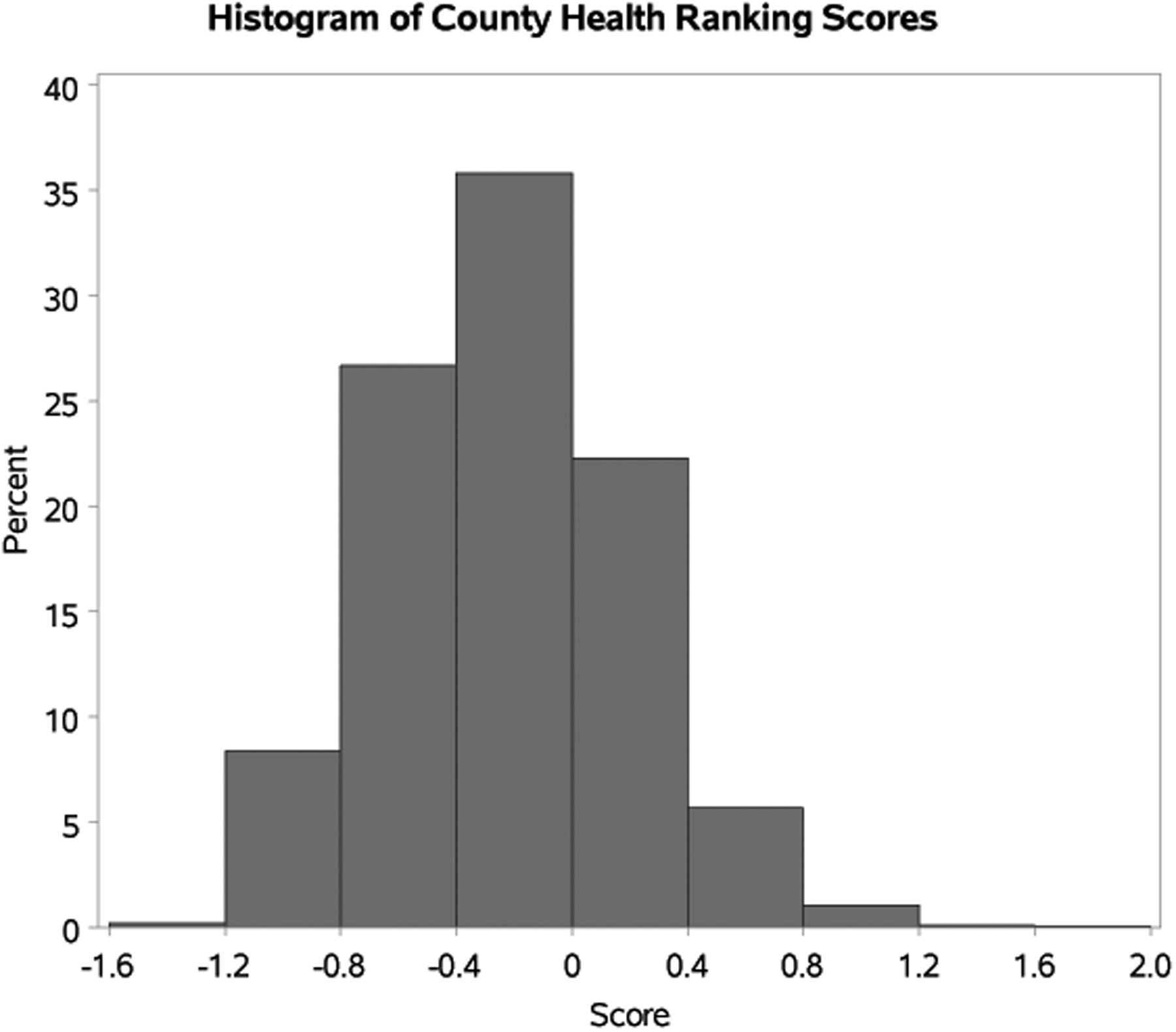

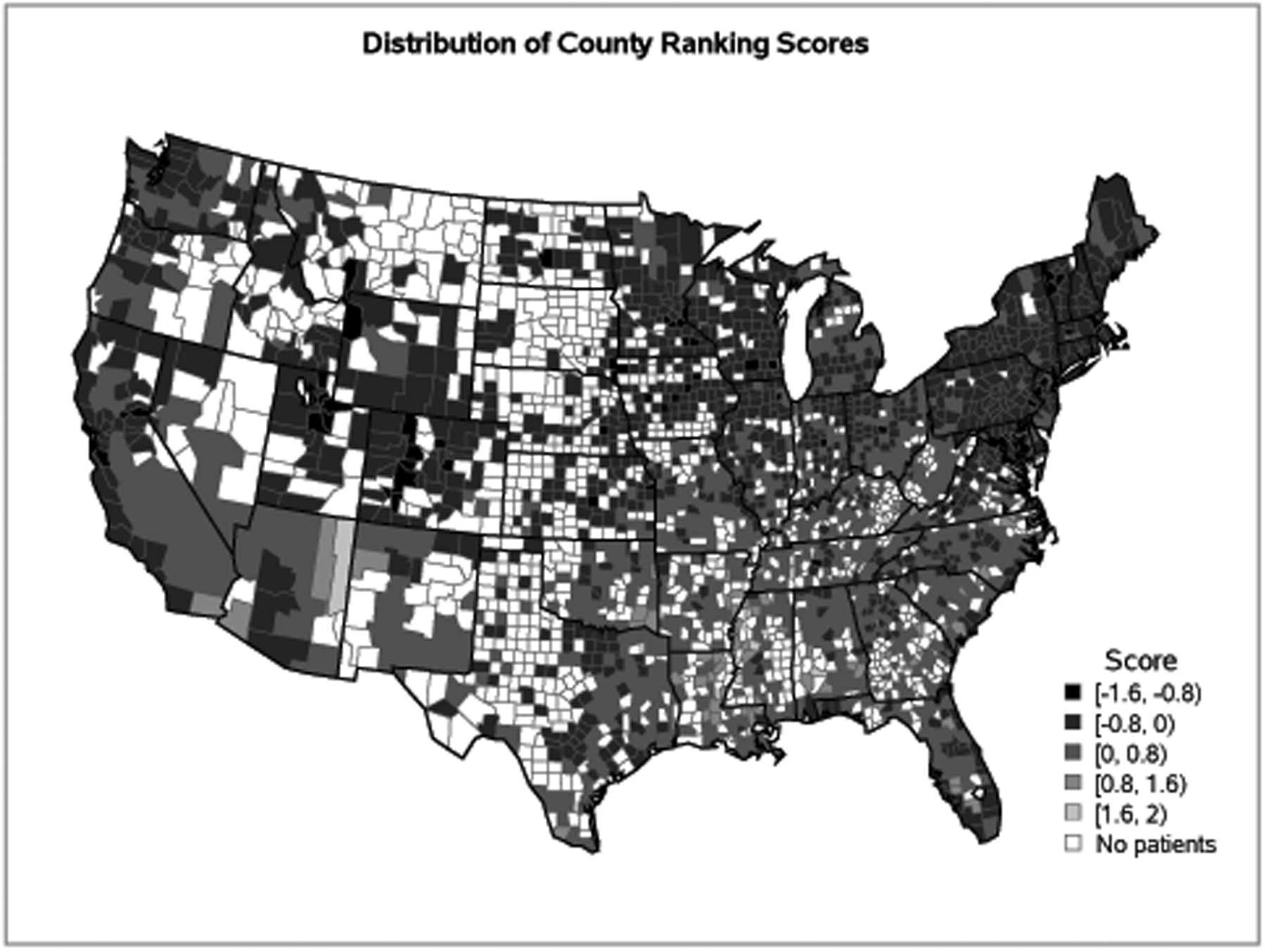

The median follow-up of survivors for the whole cohort was 24 months (range, 1.5–51.8 months). Median age at HCT was 55 years (range, 18–83 years); 20% were <40 years, and 21% were ≥65 years in age at the time of their HCT (Table 1). The distribution of community health status score is described in Figure 1. Figure 2 represents the distribution of the community health status score of the patients included in the cohort by geographic location in the US. The median PCS was −0.21 (interquartile range [IQR] −0.53 to 0.03), and the median CCS was −0.13 (IQR −0.43 to 0.12). Pearson correlation coefficient between PCS and CCS was r=0.3. This represented a weakly positive linear relationship between PCS and CCS.

Figure 1. Numerical Distribution of County Ranking Scores on Adult Allogeneic Transplant Patient Residence in the United States.

*Note: lower scores are better health factor rankings, while higher scores are worse health factor rankings. Z-score of 0 was the normalized average for all US counties.

Figure 2. Map of County Ranking Scores on Adult Allogeneic Transplant Patient Residence in the United States.

*Note: Lower scores, represented by lighter grey colors, are better health factor rankings, while higher scores, represented by darker grey colors, are worse health factor rankings. White areas did not have transplant recipients.

PCS, CCS, and HCT Outcomes

In our first analysis evaluating the relationship of PCS and CCS with recipient outcomes (Table 2), higher PCS was associated with inferior overall survival (OS) in Cox regression multivariable analysis (hazard ratio [HR] 1.04 per one SD increase in PCS, 99% CI [1.00–1.08], p=0.0089). On the other hand, CCS was not significantly associated with OS (HR 1.01, 99% CI [0.98–1.04], p=0.54).

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis of Community Health Status and Transplant Outcomes in Adult Recipients of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation

| Population | Outcome | Variable | HR (99% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n=18,544) | Overall mortality | PCS | 1.04 (1.00 – 1.08) | 0.0089 |

| CCS | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.04) | 0.5379 | ||

| Patients with hematologic malignancies (n=17,793) | Overall mortality | PCS | 1.04 (1.00 – 1.08) | 0.0102 |

| CCS | 1.01 (0.97 – 1.04) | 0.6658 | ||

| Relapse | PCS | 0.97 (0.94 – 1.01) | 0.0441 | |

| CCS | 1.00 (0.96 – 1.04) | 0.9310 | ||

| Non-relapse mortality | PCS | 1.08 (1.02 – 1.15) | 0.0004 | |

| CCS | 1.02 (0.97 – 1.07) | 0.3106 |

CCS = center community-risk sore; PCS= patient community-risk score.

Hazard ratio (HR) quantifies risk change corresponding to one standard deviation increase in continuous covariate.

Bolded variables indicate a significant association defined by p≤0.01. All models included the following significant co-variables: diagnosis, disease status/ stage, donor type, HCT-comorbidity index, HLA matching, recipient age, donor age for unrelated BM or PBSC donors, recipient and donor gender, recipient and donor CMV serologies, recipient’s self-reported race and ethnicity, donor race, donor ethnicity, donor parity, recipient’s performance status score at transplant, prior autologous transplant, resistant disease in lymphoma only, NHL subtype, time from diagnosis to transplant for AML or ALL not in CR1 or PIF, AML transformed from MDS or MPN disease, therapy related AML or MDS, AML ELN risk group, number of induction cycles to achieve latest CR before HCT for AML and ALL patients, year of transplant, T-cell lineage in ALL, Philadelphia chromosome in ALL, ALL cytogenetic risk group, ALL molecular marker (BR/ABL at any time between diagnosis and HCT), MDS with predisposing conditions, MDS IPSS-R prognostic risk category/ score at HCT, deletion 17p in CLL, MM cytogenetics risk group, MM ISS at diagnosis, plasma cell disorder disease status at HCT, plasma cell leukemia, history of mechanical ventilation, history of invasive fungal infection, and median household income based on ZIP Code of residence of recipient.

In patients with hematologic malignancies, higher PCS had a tendency towards with inferior OS (HR 1.04 per 1 SD increase, 99% CI [1.00–1.08], p=0.0102; Table 2). This tendency was primarily driven by higher NRM in patients with higher PCS (HR 1.08, 99% CI [1.02–1.15], p=0.0004). As in the analysis of all patients, we observed no association of CCS with OS, NRM, or relapse among HCT recipients with hematologic malignancies (Table 2). Full results of multivariate analysis are included in Supplemental Tables 1–4. Due to the nature of our PCS and CCS calculations, results are not available in each outcome.

PCS, CCS, and Center-Specific Analysis

For this secondary analysis, we tested PCS and CCS in the pseudo-value logistic regression model from the 2018 CIBMTR center-specific analysis, while adjusting for all patient-, disease- and transplant-related variables considered in that particular model. Neither PCS (odds ratio [OR] 1.03, 95% CI 0.99–1.08, p=0.11) nor CCS (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.99–1.06, p=0.24) were significantly associated with 1-year odds of OS.

DISCUSSION

A complex network of social, physical, and environmental factors influence health care access, delivery, and outcomes in allogeneic HCT.3,26,27 In our first of its kind study using a comprehensive assessment of patient- and center-related health disparity factors using the CHRR, we demonstrate that allogeneic HCT recipients who reside in counties with poor overall community health status have lower survival and that this is primarily driven by a higher risk of NRM. However, patient survival was not determined by community health status of the county where their transplant center was located. Furthermore, neither patient nor center community health status was associated with one-year odds of OS using the exact same model, parameters, and significance level that are currently used in the CIBMTR center-specific analysis model.13,15

The association between community health status of patient residence and their survival and risks of NRM supports our hypothesis that worse community health and healthcare resources surrounding a patient’s residence negatively influence post-HCT course. Previous studies have evaluated the relationship of individual sociodemographic variables such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status with post-HCT survival.1,4,7 This study discovered a need to recognize the patient’s community health status as an additional potentially modifiable prognostic factor. Poor community health may be linked to poor mechanisms for follow-up and lack of family or personal resources to address HCT complications. In light of this, HCT centers can develop a strategy to improve close follow-up and check-ins with patients from areas of high community risk. Also, dedicating additional resources to the focused areas can advance the overall community health.

In contrast, the lack of association of community risk of center location with patient survival can be supported by the following: First, many transplant candidates are referred by local physicians to distant transplant centers and return to their residence after alloHCT. Second, there can be other important community health factors not captured by the CHRR. Third, community health status at centers may not influence clinical practice of transplant centers. Fourth, some of the variables assessing the community health status may interact and correlate with covariates in the model that we tested.

Addition of PCS or CCS did not change the 2018 center-specific analysis model. In the current study, neither PCS nor CCS was shown to be independent predictors of one-year OS considered in the pseudo-value logistic regression model. The latter approach models survival at one-year time point from transplant, which is quite different from the time to event analysis behind the Cox model focused on the instantaneous hazard rate over the entire follow up period. Inherent statistical methodology differences between the pseudo-value logistic regression and Cox regression may be responsible for the difference in prognostic value of PCS.

To our knowledge, this study is the first successful attempt to establish a community score model across the US for HCT. A previous study was limited by small sample size and limited community variation.28 Otherwise, studying community factors was a new concept in the field of HCT. Outside of the field of HCT, ten variables from CHRR were derived to create a kidney transplant specific community risk score model that had significant associations with waitlist mortality and transplant outcomes.10,11 Now, we have derived a new scoring system from CHRR that can be used in other studies to describe disparities in the context of HCT comprehensively.

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. The disparity related factors were evaluated at the county level (vs. zip code level), which can be a rather broad geographic unit to describe an individual patient’s situation. However, the county-level community health status has been used and validated in many other studies.10,11,29 The current results are only applicable to the US. Also, due to the nature of the CIBMTR registry, we did not study access to HCT. Also, a small number of recipients may have relocated from their residence during the post-HCT period.

While revealing the presence of community risk in HCT, this study raises more important questions to be answered. Disparities in access to HCT has been well described in the literature.2,3,8,26,27,30–32 However, we could not study the association of community health factors with access since our dataset only included information on patients who were able to receive transplantation. It is possible that the relatively low median/range of PCS indirectly reflects lower rates of referral for patients from “less healthy” communities. We also recognize that the interaction between socio-demographic factors and health status is complex. For example, it is possible that patients residing in less healthy communities may be more likely to have comorbidities that makes them less favorable candidates for transplantation. It is important to continue to better understand these barriers to access to HCT and a detailed data source such as CHRR may facilitate future studies in this area. Furthermore, while the CHRR data reflect health factors and outcomes for the general population, not all health factor measures may influence HCT outcomes. Creating a HCT-specific community risk score model by assessing individual community factors is another important next step.

Currently, practices in post-transplant care are varied among transplant centers depending on community health care models in the US.33 Patients from communities with inadequate resources, reflected by worse PCS, likely need resources and attention to overcome this additional risk. In conclusion, as community health of patient residence is associated with post-alloHCT overall and non-relapse mortalities, more studies are needed to understand and mitigate these disparities.

Supplementary Material

Funding Support:

Navneet Majhail is partially supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01-CA215134). The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); U24HL138660 from NHLBI and NCI; R21HL140314 and U01HL128568 from the NHLBI; HHSH250201700006C, SC1MC31881-01-00 and HHSH250201700007C from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); and N00014-18-1-2850, N00014-18-1-2888, and N00014-20-1-2705 from the Office of Naval Research; Additional federal support is provided by P01CA111412, R01CA152108, R01CA215134, R01CA218285, R01CA231141, R01HL126589, R01AI128775, R01HL129472, R01HL130388, R01HL131731, U01AI069197, U01AI126612, and BARDA. Support is also provided by Be the Match Foundation, Boston Children’s Hospital, Dana Farber, Japan Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Data Center, St. Baldrick’s Foundation, the National Marrow Donor Program, the Medical College of Wisconsin and from the following commercial entities: AbbVie; Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Adaptive Biotechnologies; Adienne SA; Allovir, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Anthem, Inc.; Astellas Pharma US; AstraZeneca; Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc.; bluebird bio, Inc.; Bristol Myers Squibb Co.; Celgene Corp.; Chimerix, Inc.; CSL Behring; CytoSen Therapeutics, Inc.; Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.; Gamida-Cell, Ltd.; Genzyme; GlaxoSmithKline (GSK); HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Janssen Biotech, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen/Johnson & Johnson; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Kiadis Pharma; Kite Pharma; Kyowa Kirin; Legend Biotech; Magenta Therapeutics; Mallinckrodt LLC; Medac GmbH; Merck & Company, Inc.; Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; Mesoblast; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; Novartis Oncology; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Omeros Corporation; Oncoimmune, Inc.; Orca Biosystems, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc.; Phamacyclics, LLC; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; REGiMMUNE Corp.; Sanofi Genzyme; Seattle Genetics; Sobi, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; Takeda Pharma; Terumo BCT; Viracor Eurofins and Xenikos BV. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial conflict of interest to disclose in relation to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fu S, Rybicki L, Abounader D, et al. Association of socioeconomic status with long-term outcomes in 1-year survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(10):1326–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majhail NS, Nayyar S, Santibanez ME, Murphy EA, Denzen EM. Racial disparities in hematopoietic cell transplantation in the united states. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(11):1385–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majhail NS, Omondi NA, Denzen E, Murphy EA, Rizzo JD. Access to hematopoietic cell transplantation in the united states. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(8):1070–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamilton BK, Rybicki L, Arai S, et al. Association of socioeconomic status with chronic graft-versus-host disease outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(2):393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denzen EM, Thao V, Hahn T, et al. Financial impact of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation on patients and families over 2 years: Results from a multicenter pilot study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51(9):1233–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong S, Rybicki L, Corrigan D, et al. Psychosocial assessment of candidates for transplant (PACT) as a tool for psychological and social evaluation of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw BE, Logan BR, Kiefer DM, et al. Analysis of the effect of race, socioeconomic status, and center size on unrelated national marrow donor program donor outcomes: Donor toxicities are more common at low-volume bone marrow collection centers. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(10):1830–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshua TV, Rizzo JD, Zhang MJ, et al. Access to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Effect of race and sex. Cancer. 2010;116(14):3469–3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remington PL, Catlin BB, Gennuso KP. The county health rankings: Rationale and methods. Popul Health Metr. 2015;13:11-015-0044-2. eCollection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schold JD, Buccini LD, Kattan MW, et al. The association of community health indicators with outcomes for kidney transplant recipients in the united states. Arch Surg. 2012;147(6):520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schold JD, Heaphy EL, Buccini LD, et al. Prominent impact of community risk factors on kidney transplant candidate processes and outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(9):2374–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Qurayshi Z, Randolph GW, Srivastav S, Kandil E. Outcomes in endocrine cancer surgery are affected by racial, economic, and healthcare system demographics. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(3):775–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logan BR, Nelson GO, Klein JP. Analyzing center specific outcomes in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Lifetime Data Anal. 2008;14(4):389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR). U.S. transplant and survival statistics on related sites. http://www.cibmtr.org/ReferenceCenter/SlidesReports/USStats.Updated2018. AccessedJune 4, 2019.

- 15.US Department of Health and Human Services - Health Resources and Services Administration, Blood Cell Transplant. U.S. patient survival report. http://bloodcell.transplant.hrsa.gov/research/transplant_data/us_tx_data/survival_data/survival.aspx. Updated 2019. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- 16.Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR). “Methodology employed for annual report on hematopoietic cell transplant center-specific survival rates”. https://www.cibmtr.org/Meetings/Materials/CSOAForum/Documents/Center_Forum_Summary2010.pdf. Updated2018. AccessedAugust 24, 2019.

- 17.Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR). “Recommendations from the 2010 center-specific outcomes analysis forum”. https://www.cibmtr.org/Meetings/Materials/CSOAForum/Documents/Center_Forum_Summary2010.pdf. Updated 2010. Accessed August 24, 2019.

- 18.University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County health rankings & roadmaps. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/.Updated2019. AccessedJune 9, 2019.

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. County cross reference file (FIPS/ZIP4). https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/sci_data/codes/fips/type_txt/cntyxref.asp.Updated2016. AccessedDecember 27, 2018.

- 20.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: A new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106(8):2912–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moorman AV, Chilton L, Wilkinson J, Ensor HM, Bown N, Proctor SJ. A population-based cytogenetic study of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(2):206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, et al. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120(12):2454–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, et al. Revised international staging system for multiple myeloma: A report from international myeloma working group. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(26):2863–2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: Working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(12):1628–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell JM, Meehan KR, Kong J, Schulman KA. Access to bone marrow transplantation for leukemia and lymphoma: The role of sociodemographic factors. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(7):2644–2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell JM, Conklin EA. Factors affecting receipt of expensive cancer treatments and mortality: Evidence from stem cell transplantation for leukemia and lymphoma. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(1):197–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong S, Rybicki LA, Corrigan D, Schold JD, Majhail NS. Community risk score for evaluating health care disparities in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(4):877–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schold JD, Phelan MP, Buccini LD. Utility of ecological risk factors for evaluation of transplant center performance. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(3):617–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paulson K, Brazauskas R, Khera N, et al. Inferior access to allogeneic transplant in disadvantaged populations: A center for international blood and marrow transplant research analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costa LJ, Huang JX, Hari PN. Disparities in utilization of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for treatment of multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(4):701–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schriber JR, Hari PN, Ahn KW, et al. Hispanics have the lowest stem cell transplant utilization rate for autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma in the united states: A CIBMTR report. Cancer. 2017;123(16):3141–3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khera N, Martin P, Edsall K, et al. Patient-centered care coordination in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood Adv. 2017;1(19):1617–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.