Abstract

Purpose:

To assess rural-urban differences in dental service use and procedures and to explore the interaction effects of individual and county-level factors on having dental service use and procedures.

Methods:

Data were from the 2016 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). We assessed rural-urban differences in three outcome variables: number of dental visits (1, 2, or 3+ visits), preventive care procedures (Yes/No), treatment procedures (Yes/No). The study sample included 8,334 adults ≥ 18 years of age who reported at least one dental visit in the past year. Sampling weights embedded in MEPS were incorporated into all the analyses.

Findings:

A significant interaction between residential location and race/ethnicity (p=0.030) suggested limited access to dental visits for minority groups especially for blacks in the more rural areas. Adults from a more rural area were less likely to have received a preventive procedure (AOR=0.55, 95% CI: 0.35-0.87) than those from an urban area. Adults of racial/ethnic minority groups, with lower SES, and without dental insurance were less likely to have received a preventive procedure (all p<0.01), but were more likely to have received a treatment procedure (all p<0.05).

Conclusions:

The study showed rural adults were less likely to have received preventive dental procedures than their urban counterparts. Racial/ethnic minority groups living in a more rural area had even more limited access to dental services. Innovative service delivery models that integrate tele-health and community-based case management may contribute to addressing these gaps in rural communities.

Introduction

Approximately 59 million Americans reside in rural or partially rural areas that have been designated by the US Health Resources and Services Administration as Dental Health Professional Shortage Areas (DHPSAs).1 Limited access to dental services and poor oral health among rural residents have been well documented.2-5 Yet most prior research on dental care access has focused on a dichotomous outcome— visiting a dentist or not,6,7 without determining different types of dental services received. However, in addition to limited access to dental services,8 rural residents may also experience disparities in the types of dental services received once they have accessed dental care, such as being more likely to have visits based on a need for restorative care or to only have visits on an episodic basis, i.e., for tooth extraction. They may also be less likely to utilize comprehensive care in a chronic disease management framework that involves regular preventive visits such as dental cleaning. In this way, service type can be an indicator of quality of care.17

A few studies have examined receipt of dental procedures by rural and urban residents and found disparities in dental care for rural residents.9-11 Most of these studies focused on certain states and did not have a national scope. A key exception is the study by Goodman and Manski that assessed one type of dental service— preventive dental procedures in the US. They found that respondents (all age groups) residing in a nonmetropolitan area were less likely to report having had a preventive dental care visit than were respondents residing in large or small metropolitan areas.9

There is limited national data comparing types of dental services received by rural and urban adults. A better knowledge of rural-urban differences in the types of dental procedures will provide additional insights on rural/urban disparities in dental procedures and inform dental services planning and workforce development. This study aimed to assess dental procedure utilization patterns among rural and urban adults who have reported at least one dental visit in the past year. Specifically, the objectives were to assess differences in dental visits and service type received, defined as preventive procedures, and treatment procedures, among rural and urban adults; and to explore whether there are cross-level effects of both individual and county-level factors on dental visits and procedures. For instance, whether those with lower SES and also living in a rural community were more likely to have received treatment but less likely to have received a preventive procedure.

Methods

Data source

Data were from the 2016 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). MEPS provides nationally representative estimates of health care use, expenditures, sources of payment, and health insurance coverage for the US civilian noninstitutionalized population. Detailed information about MEPS can be found elsewhere.12 The variables used in this analysis were from the MEPS Household component (demographics and SES data) and the Dental Event Files (types of dental providers and procedures). Rural and urban location data were obtained from the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ). The sample for this analysis included respondents who reported at least one dental visit to any type of dental professionals in the past year, including general dentists, dental hygienists, dental technicians, and dental specialists—8,199 adults ≥ 18 years who participated in the 2016 MEPS survey.

Outcome variables

This study assessed three outcome variables of dental care:

Number of dental visits (1, 2, or 3+ visits). In MEPS, the total number of dental visits includes visits to general dentists, dental hygienists, dental technicians, dental surgeons, orthodontists, endodontists, or periodontists. Based on the distribution of dental visits by respondents with at least one dental care visit, the variable was measured at the ordinal level in this analysis: 1, 2 or 3+ visits, in the past year.

Preventive care procedure (Yes/No).

Treatment procedure (Yes/No), which included the restorative, prosthetic, periodontic, endodontic, oral surgery, orthodontic, and other procedures.

Thus, the first outcome variable measures “total” utilization, while the other two variables measure the type of services received at the last visit, capturing the “purpose” of the last dental visit: The type of dental procedure received can be an indicator of quality of care. In the MEPS survey, respondents were asked about the dental procedures they received during the dental visit.13 We did not include diagnostic procedures as a separate category in this analysis as they are generally reported together with the preventive or treatment procedures.14

Covariates

Covariates were selected according to the Andersen’s behavioral model of health service utilization,15 which suggests that improving access to care requires focusing on both individual and contextual characteristics. The Andersen’s model includes predisposing, enabling, and need factors as determinants and has been adapted to oral health care research.16

Individual level variables were demographic variables (predisposing factors), SES variables (enabling factors), health status (need factor). Demographic variables included age (18-44, 45-64, and ≥65), sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic [regardless of race], and other), married (Yes/No), employed (Yes/No); SES variables were 1) Family income level. It is the percent of federal poverty line (FPL) for the total family income, adjusted for family size and composition.17 We classified as low income (less than 200 percent of FPL, middle income (200-400 percent of the FPL), and high income (greater than 400 percent of FPL). 2) Educational attainment level (less than high school graduate, high school graduate, and some college or above), and 3) Dental insurance (Yes/No). Health status included self-reported health status (excellent/very good, good, and fair/poor).

Contextual factors refer to the characteristics of the community where an individual lives, which describe the milieu where health utilization takes place. These contextual factors are considered to shape the resources and opportunities available to individuals in the community.18 The components of contextual characteristics were classified in the same way as individual characteristics introduced above. Predisposing conditions included community factors that are indicative of the probability to seek health care. We included 4 variables: proportion of population in the county who were Black/African American, unemployment rate, and percentage of county residents with less than a high school education. Enabling conditions include factors that could make access to dental care easier. We included 5 variables: county median household income, presence of at least one Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) (Yes/No), designation as a Dental Health Professional Shortage Area (DHPSA) (Not, whole county, and part of the county), geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and finally, residential location, defined by the Rural Urban Continuum Code (RUCC), which classifies metropolitan counties by the population size of their metro area, and nonmetropolitan counties by degree of urbanization and adjacency to a metro area.19 In this analysis we classified RUCC categories 1-3 as urban residence and RUCC categories as 4-9 rural residence. For the rural residence, we further combined RUCC 4, 6, and 8 as non-metro, adjacent to a metro area (“rural area, adjacent to a city” hereinafter), RUCC 5, 7, and 9 as non-metro, not adjacent to a metro area (“rural area, not adjacent to a city” hereinafter); thus the latter rural category is more rural. We did not include a contextual need factor as it is not available.

Statistical analysis

We used logistic regression models to analyze the effects of individual and county level factors on the three outcome variables. For the number of dental visits variable, we used an ordinal logistic regression model (Model I); for the other three outcome variables—preventive (Model II), treatment (Model III), and both preventive and treatment procedures (Model IV), we used binary logistic regression models. In all these three models, we tested three interaction terms: residence by race/ethnicity, residence by family income, and residence by education level to evaluate the moderating effect of rural residence. The interaction terms were removed from the final model if not significant. Significance level was set at p<0.05. We conducted multicollinearity analysis and did not find multicollinearity (VIF=1.9). We also checked the assumptions for proportional odds in Model I. We conducted the analyses at the Agency of Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) Data Center in Washington, DC in April 2019. Sampling weights embedded in MEPS were incorporated into all the analyses to obtain national estimates. Data analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

Sample characteristics

About 38.9% of the respondents (with ≥ 1 dental visit) were 18-44 years of age, 37.0% were 45-64 years of age, and 24.2% were 65 years or older; 73.8% were non-Hispanic whites, 7.4% were non-Hispanic blacks, 10.4% Hispanic, and 8.4% others; 47.2% had dental insurance; 88.3% were from an urban area, 8.6% from a rural area, adjacent to a city, 3.1% from a rural area not adjacent to a city. About 42.1% had one dental visit, 31.2% had two visits, and 26.7% had three or more visits. About 82.2% had a preventive care procedure and 43.4% had a treatment procedure (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics: The 2016 MEPS(N=8199)

| Variables | All %, mean (95% CI) |

Residence location %, mean (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural, adjacent to city |

Rural, not adjacent to city |

P | ||

| Individual level variables | 88.3 (86, 90.5) | 8.6 (6.2, 11) | 3.1 (1.7, 4.6) | ||

| Age | 0.014 | ||||

| 18-44 | 38.9 (37.1, 40.6) | 39.7 (37.8, 41.6) | 34.3 (28.2, 40.4) | 28.9 (22.1, 35.7) | |

| 45-64 | 36.9 (35.5, 38.4) | 36.8 (35.1, 38.4) | 39.0 (34.3, 43.7) | 35.9 (28.6, 43.2) | |

| 65+ | 24.2 (22.6, 25.7) | 23.5 (21.9, 25.2) | 26.7 (20.2, 33.2) | 35.2 (26.9, 43.6) | |

| Sex | 0.985 | ||||

| Female | 56.3 (55.3, 57.2) | 56.3 (55.3, 57.3) | 56.1 (52.7, 59.5) | 56.7 (50, 63.4) | |

| Male | 43.7 (42.8, 44.7) | 43.7 (42.7, 44.7) | 43.9 (40.5, 47.3) | 43.3 (36.6, 50) | |

| Married | 0.223 | ||||

| Yes | 59.7 (58.1, 61.3) | 59.1 (57.4, 60.9) | 63.9 (58.9, 68.9) | 63.7 (53.3, 74.1) | |

| No | 40.3 (38.7, 41.9) | 40.9 (39.1, 42.6) | 36.1 (31.1, 41.1) | 36.3 (25.9, 46.7) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 73.8 (72, 75.6) | 71.7 (69.8, 73.7) | 88.4 (84.5, 92.2) | 92 (88.7, 95.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 7.4 (6.5, 8.3) | 8.0 (7.0, 8.9) | 3.2 (1.6, 4.7) | 3.1 (0.3, 5.9) | |

| Hispanic | 10.4 (9.3, 11.5) | 11.3 (10, 12.5) | 4.6 (1.6, 7.6) | 2.5 (0.1, 4.9) | |

| Other | 8.4 (7.2, 9.6) | 9.0 (7.7, 10.4) | 3.9 (1.4, 6.4) | 2.4 (1.0, 3.8) | |

| Income category (% of FPL) | <.001 | ||||

| Poor/Low income | 16.5 (15.4, 17.7) | 16.2 (15, 17.4) | 19.6 (15.9, 23.2) | 17.6 (11.1, 24.1) | |

| Middle income | 25.1 (23.8, 26.4) | 24 (22.7, 25.4) | 32.8 (27.9, 37.8) | 32.3 (23.8, 40.7) | |

| High income | 58.4 (56.7, 60.1) | 59.8 (58, 61.6) | 47.6 (41.6, 53.5) | 50.1 (40.7, 59.6) | |

| Education level | <.001 | ||||

| less than high school | 7.1 (6.4, 7.9) | 6.8 (6.0, 7.6) | 9.6 (7.2, 12.1) | 8.7 (4.6, 12.7) | |

| High school | 23 (21.6, 24.4) | 22 (20.6, 23.4) | 31.1 (24.5, 37.6) | 29.7 (23.1, 36.3) | |

| Some college or above | 69.9 (68.2, 71.6) | 71.2 (69.5, 72.9) | 59.3 (52.1, 66.5) | 61.7 (54.4, 68.9) | |

| Dental insurance | <.001 | ||||

| Yes | 52.9 (50.9, 54.8) | 54.2 (52.1, 56.2) | 45.9 (39.7, 52.1) | 35.2 (25.7, 44.6) | |

| No | 47.1 (45.2, 49.1) | 45.8 (43.8, 47.9) | 54.1 (47.9, 60.3) | 64.8 (55.4, 74.3) | |

| Employment status | 0.017 | ||||

| Employed | 68.7 (67.2, 70.2) | 69.1 (67.5, 70.8) | 67.5 (62.9, 72.2) | 58.5 (51.2, 65.9) | |

| Not Employed | 31.3 (29.8, 32.8) | 30.9 (29.2, 32.5) | 32.5 (27.8, 37.1) | 41.5 (34.1, 48.8) | |

| Health status | <.001 | ||||

| Excellent/very good | 63.9 (62.6, 65.2) | 64.9 (63.5, 66.4) | 53.5 (49.3, 57.7) | 63.1 (54, 72.2) | |

| Good | 26.3 (25.2, 27.4) | 26 (24.8, 27.1) | 31.2 (27, 35.3) | 23.4 (15.1, 31.7) | |

| Fair/Poor | 9.8 (9.0, 10.6) | 9.1 (8.3, 9.9) | 15.3 (10.8, 19.9) | 13.5 (8.1, 18.9) | |

| County level variables | |||||

| County unemployment rate (Mean)a | 5.5 (5.4, 5.5) | 5.4 (5.3, 5.6) | 5.6 (5.5, 5.8) | 5.3 (5.2, 5.5) | 0.007 |

| Median household income (Mean) ($1000) a | 49.5(49.1, 50.0) | 56.8 (56.0, 57.6) | 45.0 (44.5, 45.6) | 45.5(44.8, 46.1) | <.001 |

| Percentage of county residents with less than high school (Mean)a | 14.5 (14.3, 14.8) | 13.4 (13.1, 13.8) | 16.0 (15.6, 16.4) | 14.5 (14.0, 14.9) | <.001 |

| County black population rate (Mean) a | 9.0 (8.5, 9.5) | 11.0 (10.2, 11.7) | 9.8 (8.8, 10.8) | 5.4 (4.6, 6.2) | <.001 |

| FQHC | <.001 | ||||

| Yes | 92.0 (89.8, 94.1) | 95.1 (93.4, 96.7) | 74.9 (61.2, 88.6) | 51.1 (25.9, 76.4) | |

| No | 8.0 (6.6, 11.2) | 4.9 (3.3-6.6) | 25.1 (11.4-38.8) | 48.9 (23.6-74.1) | |

| DHPSA | <.001 | ||||

| Whole county | 1.6 (0.9, 2.3) | 0.7 (0.3, 1) | 7.7 (2, 13.4) | 10.5 (0.4, 20.6) | |

| Part county | 84.2 (80.7, 87.7) | 87 (83.3, 90.6) | 62.7 (47.5, 77.9) | 66 (42, 90) | |

| No | 14.2 (10.8, 17.6) | 12.4 (8.8, 16) | 29.6 (14.3, 45) | 23.5 (0, 47) | |

| Region | 0.048 | ||||

| Northeast | 19.5 (17.5, 21.5) | 20.5 (18.5, 22.5) | 12.1 (2.7, 21.6) | 11.9 (0, 30) | |

| Midwest | 22.7 (20.2, 25.1) | 21.2 (18.5, 23.8) | 28.7 (15.5, 41.9) | 48.2 (24.1, 72.3) | |

| South | 32 (29.7, 34.3) | 31.3 (28.8, 33.9) | 38.4 (25.2, 51.5) | 33.2 (13.8, 52.5) | |

| West | 25.8 (23.5, 28.2) | 27 (24.4, 29.7) | 20.8 (9, 32.7) | 6.8 (0, 14.7) | |

| Outcome variables | |||||

| Dental visits | 0.576 | ||||

| 1 | 42.1 (40.6, 43.6) | 42.0 (40.4, 43.6) | 42.3 (35.9, 48.6) | 45.1 (36.5, 53.8) | |

| 2 | 31.2 (30, 32.5) | 31.1 (29.8, 32.5) | 30.7 (26.8, 34.5) | 34.6 (26.9, 42.2) | |

| 3+ | 26.7 (25.4, 28) | 26.9 (25.5, 28.3) | 27.1 (22.6, 31.5) | 20.3 (13.3, 27.3) | |

| Preventive procedures | <.001 | ||||

| Yes | 82.2 (81.2, 83.3) | 83.0 (82.0, 84.1) | 78.3 (74.3, 82.2) | 70.9 (61.5, 80.3) | |

| No | 17.8 (16.7, 18.8) | 17.0 (15.9, 18.0) | 21.7 (17.8, 25.7) | 29.1 (19.7, 38.5) | |

| Treatment Procedures | 0.226 | ||||

| Yes | 43.4 (41.9, 44.9) | 42.9 (41.3, 44.5) | 46.6 (42, 51.2) | 48.5 (38.2, 58.8) | |

| No | 56.6 (55.1, 58.1) | 57.1 (55.5, 58.7) | 53.4 (48.8, 58) | 51.5 (41.2, 61.8) | |

FPL=federal poverty line

As for the characteristics of the respondents by the 3 types of rural-urban residential status, a larger proportion of respondents in urban areas were in the age group 18-44 years old, were non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics, had higher income and education levels, were currently employed, had dental insurance, and have received preventive procedures than those in rural areas (adjacent and not adjacent to a city), while a smaller proportion of respondents in urban areas self-reported poor/fair health status, and had treatment procedures (All ps <0.01) (Table 1).

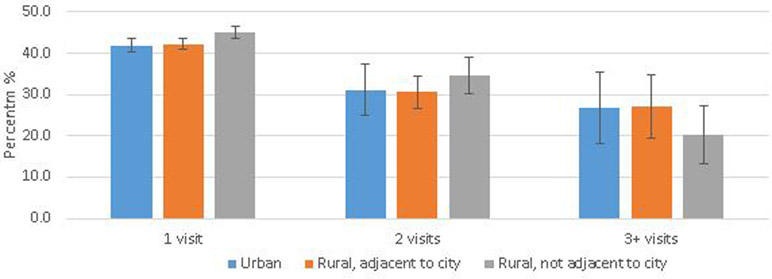

Distribution of the outcome variables by rural/urban residential status

Figures 1a displays the distribution of dental visits by residential status. No significant differences were shown (p=0.58) in the proportions having 1, 2, or 3+ visits by the three residential locations. For example, the proportions having 3+ visits were 26.9% (95% CI: 25.5-28.3%) for urban respondents, 27.1% (95% CI: 22.6-31.5%) for residents from rural, adjacent to a city, 20.3% (95% CI: 13.3-27.3%) for residents from rural not adjacent to a city. On average, urban residents had 2.18 visits (95% CI: 2.13-2.23), residents from rural, adjacent to a city had 2.19 visits (95% CI: 2.04-2.34), and residents from rural, not adjacent to a city had 2.06 visits (95% CI: 1.74-2.38) (Data not shown in the figure).

Figure 1a.

Proportion having dental visits, by residence location

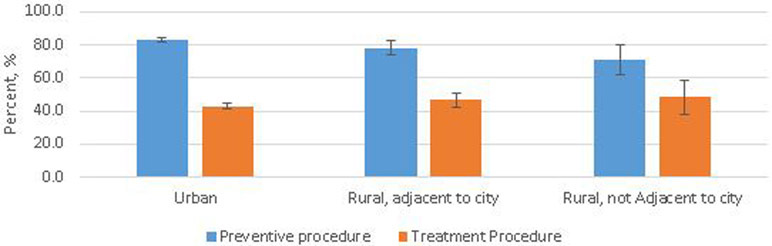

Figure 1b shows the proportions having received preventive and treatment dental procedures. Significant differences were shown in having preventive procedures (p<0.001) by the three residential locations. Respondents from an urban area were more likely to have received a preventive procedure than those from a rural area, adjacent to a city, and rural, not adjacent to a city: 83.0% (95% CI: 82.0-84.1%), vs 78.3% (95% CI: 74.3-82.2%), and 70.9% (95% CI: 61.5-80.3%).

Figure 1b.

Proportions having a preventive or treatment procedure, by residence location

No significant differences were shown in having received a treatment procedure by residential locations (p=0.227). 42.9% (95% CI: 41.3-44.5%) of respondents from an urban area had received a treatment procedure, 46.6% (95% CI: 42.0-51.2%) for those from rural, adjacent to city, and 48. 5% (95% CI: 38.2-58.8%) for those from rural, not adjacent to a city.

Logistic regression model results

Interaction terms

For Model I, we checked the ordinal model assumptions. Given the modest sample size for the interaction terms, we decided to use proportional odds model. We also checked the multicollinearity of the covariates and did not detect multicollinearity (VIF<XXX). In Model I, a significant interaction effect was found between residential location and race/ethnicity (p=0.030), indicating limited access to dental care for adults of racial/ethnic minority groups, especially for non-Hispanic blacks in the more rural areas. For instance, non-Hispanic blacks and living in a rural not adjacent to a city were more likely to have fewer dental visits (AOR=4.79, 95% CI: 1.39-16.56). This rural-urban residential location by race/ethnicity interaction term was not statistically significant in the other three models (all p>0.05), so it was removed from the models. The other two interaction terms—residential location by family income, and residential location by education level—were not significant. Insignificant interaction terms are not presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Logistic regression model results: The 2016 MEPS (n=8199)

| Variables | Model I DV=Dental visits |

Model II DV=Preventive procedure |

Model III DV=Treatment procedure |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | ||||

| Age (vs. 18-44) | <.001 | 0.396 | 0.003 | |||||||||

| 45-64 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.85 | <.001 | 0.99 | 0.84 | 1.15 | 0.847 | 1.19 | 1.03 | 1.37 | 0.017 |

| 65+ | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.63 | <.001 | 1.16 | 0.90 | 1.48 | 0.248 | 1.32 | 1.11 | 1.57 | 0.002 |

| Male | 1.12 | 1.03 | 1.22 | 0.009 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.97 | 0.015 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.16 | 0.355 |

| Married | 1.04 | 0.92 | 1.17 | 0.500 | 1.13 | 0.96 | 1.31 | 0.136 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.12 | 0.801 |

| Race/ethnicity (vs. Non-Hispanic white) | 0.034 | <.001 | 0.061 | |||||||||

| Non Hispanic black | 1.20 | 1.03 | 1.39 | 0.018 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.75 | <.0001 | 1.10 | 0.93 | 1.29 | 0.254 |

| Hispanic | 1.23 | 1.06 | 1.42 | 0.006 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.24 | 0.988 | 1.22 | 1.02 | 1.46 | 0.030 |

| Other | 1.17 | 1.00 | 1.36 | 0.055 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 1.13 | 0.349 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 1.10 | 0.364 |

| Family income (vs. Low income) | 0.061 | <.001 | 0.032 | |||||||||

| Mid income | 0.95 | 0.82 | 1.11 | 0.547 | 1.65 | 1.36 | 2.01 | <.001 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.99 | 0.036 |

| High income | 0.84 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.048 | 1.92 | 1.56 | 2.36 | <.001 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.95 | 0.010 |

| Education(vs. <high school) | 0.008 | <.001 | 0.020 | |||||||||

| High school | 1.00 | 0.79 | 1.26 | 0.988 | 1.49 | 1.13 | 1.96 | 0.005 | 0.84 | 0.67 | 1.06 | 0.139 |

| Some college or above | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.03 | 0.098 | 2.02 | 1.52 | 2.68 | <.001 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.92 | 0.008 |

| Dental insurance | 0.93 | 0.83 | 1.05 | 0.226 | 1.26 | 1.07 | 1.50 | 0.008 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.97 | 0.015 |

| Employed | 1.27 | 1.10 | 1.48 | 0.002 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 1.15 | 0.624 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 1.07 | 0.292 |

| Health status (vs excellent/very good) | 0.088 | <.001 | <.001 | |||||||||

| Fair/poor | 0.89 | 0.76 | 1.05 | 0.180 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.60 | <.001 | 1.40 | 1.19 | 1.64 | <.001 |

| Good | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.99 | 0.034 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.87 | <.001 | 1.33 | 1.18 | 1.50 | <.001 |

| Region (vs. Northeast) | 0.119 | 0.082 | 0.407 | |||||||||

| Midwest | 0.91 | 0.76 | 1.09 | 0.297 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 1.15 | 0.389 | 1.14 | 0.94 | 1.39 | 0.173 |

| South | 1.11 | 0.92 | 1.33 | 0.276 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.97 | 0.024 | 1.01 | 0.82 | 1.23 | 0.952 |

| West | 0.91 | 0.74 | 1.12 | 0.378 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 1.25 | 0.881 | 1.03 | 0.83 | 1.27 | 0.812 |

| Rurality (vs Urban) | 0.468 | 0.032 | 0.513 | |||||||||

| Rural, adjacent | 0.88 | 0.67 | 1.16 | 0.354 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 1.19 | 0.489 | 1.12 | 0.90 | 1.41 | 0.300 |

| Rural, not adjacent | 1.18 | 0.82 | 1.69 | 0.365 | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.87 | 0.011 | 1.21 | 0.80 | 1.82 | 0.370 |

| County level variables | ||||||||||||

| Unemployment rate | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.934 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 1.04 | 0.320 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.12 | 0.178 |

| Median household income | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.01 | 0.126 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 1.03 | 0.388 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 0.222 |

| Percentage without high school education | 2.33 | 0.59 | 9.16 | 0.223 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.91 | 0.039 | 1.38 | 0.33 | 5.77 | 0.658 |

| Black population rate | 1.15 | 0.59 | 2.21 | 0.681 | 1.40 | 0.66 | 2.96 | 0.380 | 0.72 | 0.38 | 1.38 | 0.323 |

| Presence of an FQHC | 1.03 | 0.83 | 1.29 | 0.779 | 1.02 | 0.71 | 1.46 | 0.917 | 0.94 | 0.75 | 1.18 | 0.584 |

| DHPSA (vs. Not DHPSA) | 0.036 | 0.654 | 0.210 | |||||||||

| Whole county | 1.36 | 0.89 | 2.10 | 0.158 | 1.29 | 0.75 | 2.22 | 0.356 | 0.73 | 0.42 | 1.26 | 0.258 |

| Part county | 0.86 | 0.70 | 1.04 | 0.122 | 1.03 | 0.78 | 1.36 | 0.834 | 1.11 | 0.92 | 1.34 | 0.276 |

| Residence by race/ethnicity | 0.030 | ns | ns | |||||||||

| Rural, adjacent*Black | 0.88 | 0.38 | 2.06 | 0.766 | ||||||||

| Rural, not adjacent*Black | 4.79 | 1.39 | 16.56 | 0.014 | ||||||||

| Rural, adjacent*Hispanic | 0.62 | 0.32 | 1.20 | 0.154 | ||||||||

| Rural, not adjacent*Hispanic | 0.77 | 0.30 | 1.97 | 0.580 | ||||||||

| Rural, adjacent*Other | 2.57 | 0.97 | 6.83 | 0.058 | ||||||||

| Rural, not adjacent*Other | 0.78 | 0.11 | 5.73 | 0.805 | ||||||||

Model 1 is an ordinal logistic regression. Model II and III are binary logistic regression. DV=Dependent variable. ns: Not significant. FQHC: Federally qualified health center. DHPSA: Dental health professional shortage area

Individual and contextual variables

Model I results showed that older adults (aged ≥45 years) were more likely to have more dental visits than those aged 19-44 years (p<0.001). Males (AOR=1.12, 95% CI: 1.03-1.22) and those currently employed (AOR=1.27, 95% CI: 1.10-1.48) were more likely to have fewer dental visits compared to their counterparts. Contextual level variables were not statistically significant except the DHPSA variable (an overall p=0.036) (Table 2).

Model II results showed that non-Hispanic black adults were less likely to have received a preventive procedure (AOR=0.61, 95% CI: 0.50-0.75) than non-Hispanic white adults. Adults with a higher family income or a higher education level were more likely to have received a preventive procedure (all p<0.001). Those with dental insurance were more likely to have received a preventive procedure (AOR=1.26, 95% CI: 1.07-1.50) compared to those without dental insurance. Those with good or fair/poor health status were less likely to have received a preventive procedure (p<0.001) than those with excellent/very good health status. Adults from a region designated as rural, non-adjacent to a city, were less likely to have received a preventive procedure (AOR=0.55, 95% CI: 0.35-0.87) than those from an urban area. Adults from a county with a higher rate of below high school education (AOR=0.16, 95% CI: 0.03-0.91) or from the South (AOR=0.76, 95% CI: 0.60-0.97) were less likely to have received a preventive procedure. Other contextual level variables were not significant in Model II (Table 2).

Model III results showed that adults ≥45 years were more likely to have received a treatment procedure (P=0.003) than those aged 19-44. Hispanics were more likely to have received a treatment procedure (AOR=1.22, 95% CI: 1.02-1.46) than non-Hispanic whites. Adults with middle (AOR=0.83, 95% CI: 0.70-0.99) or high income (AOR=0.80, 95% CI: 0.67-0.95) were less likely to have received a treatment procedure than those with low family income. Those adults with some college or above were less likely to have received a treatment procedure (AOR=0.74, 95% CI: 0.59-0.92) than those with less than high school education level. Those with good or fair/poor health status were more likely to have received a treatment procedure (p<0.001) than those with excellent/very good health status; adults with dental insurance were less likely to have received a treatment procedure (AOR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.74-0.97). Contextual level variables were not significant in Model III (Table 2).

Discussion

Rural oral health disparities are an important public health issue. Prior research on rural-urban oral health care disparities have focused broadly on differences in visiting a dentist. Different from prior research, this study assessed the patterns of dental use, including the number of total dental visits and types of dental procedures, and the impact of interactions of individual and contextual factors on dental use.

The interaction term of residential location by race/ethnicity was only significant in the ordinal regression model of dental visits (Model I). That is, a non-Hispanic black adult who lives in a more rural area (i.e., rural, not adjacent to a city) would have had fewer dental visits than other a white person in the same setting. In addition, the results showed that the main effects of the residence variable were not significant, but the main effects of the race/ethnicity variable were significant—Both non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics were more likely to have had fewer dentist visits than non-Hispanic whites. Given these results, even though it is not possible to ascertain the number of visits needed as no clinical diagnosis data were available, the significant interaction term suggested that the probability for blacks and living in rural communities to have used dental services was even lower. It is likely that non-Hispanic blacks in a rural community may forgo necessary follow-up dental visits. Barriers to assess dental services included poverty, lack of adequate transportation, and poor oral health education, and shortage of dental professionals in rural areas.3 For instance, only 11% of practicing dentists served rural or partially-rural communities in 2018.20 Changing the delivery model may improve access. For example, tele-dentistry has been shown to be an effective way of providing oral health services for DHPSAs.21 Several government agencies have suggested that integrating dental care with primary care can help address many oral health disparities, particularly for rural populations.22 The use of midlevel dental providers (e.g., dental therapists) 23,24 has been proposed to increase access to care to rural residents.

The results showed that adults in the more rural areas in the US were 65% less likely to have received a preventive dental procedure than their urban counterparts. In addition to the shortage of dental professionals3, other factors that could account for these results include rural residents not prioritizing oral health as a result of other needs taking precedence such as food security among those with lower SES25, as well as limited health literacy,25 or negative attitudes and perceived lack of need.26 A need for transportation could be another barrier.27 These results are concerning because lack of preventive dental care can result in a higher prevalence of dental caries, periodontal disease, tooth loss, oral cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other negative health outcomes, leading to decreased quality of life.28-30 The study results also showed that adults from southern states were less likely to have received a preventive procedure. This could be due to the lower density of health staff and physicians, which includes oral health care providers, to provide care.31

We found no statistically significant differences between rural and urban adults in receiving dental treatment procedures. However, prior research found that rural residents had poor oral health.32 Thus, we expected to observe a pattern that showed rural residents experiencing more dental treatment to address oral health problems. We did not observe this pattern and this may indicate that rural residents have unmet dental treatment needs. In this analysis, the main effect of the residence variable was not significant and it did not show they had more total dental visits, either (Model I). Model II showed rural residents were unlikely to have preventive dental visits, relative to urban residents. Taken together, these results provide additional evidence of limited access to care in rural area; rural adults have not got the dental care as needed.

The results for the individual level variables are consistent with prior findings that racial/ethnic minorities and individuals with limited financial resources had limited access to dental care compared to whites and those with higher SES status.26,33-36. It needs to be noted that more treatment procedures among older adults (but no significant results for preventive procedure) could suggest older adults had more oral health problems. Other research has found that 64% of persons 65 and older with one or more teeth having moderate or severe periodontitis;37 nearly 1 in 5 adults aged 65 years or older have untreated tooth decay.38 The demand of dental care for the elderly will be growing in the coming decades. By 2060, the number of US adults aged 65 years or older is expected to reach 98 million, 24% of the overall population.39 Older adults are keeping more of their natural teeth than in previous decades, and complete tooth loss continues to decline.40 So they would seek dental care.34 Community access to dental care and the ability of older adults to pay for dental care must be addressed to improve the health and quality of life of older adults in rural communities.41

Limitations of this study need to be considered in light of our findings. Dental procedures received are self-reported, which may be inaccurate. Multiple procedures of the same type reported during a single visit are recorded as a single procedure type. No data on the status of oral health or the intensity of the procedures are available. However, it should be noted that the MEPS is the only dataset that provides nationally representative estimates on specific procedures. Last, only two categories of the rurality were roughly classified in this study due to small sample size. This may mask variation in rurality across the country as rurality is not created equal.42 A future study using more refined categorization of rurality would help reveal variation in dental procedures and inform future initiatives to address disparities. The study sample in this study included only those having at least one dental visit. Thus a future study using refined categories of the rural-urban variable would provide more insight into the intro-rural and intro-urban variation in access to dental care. Such findings would contribute to a better understanding of the gaps in access to dental care (whether having dental visits or not) across different urban-rural residential locations.

Conclusion

The 2016 MEPS data showed rural adults were less likely to have received preventive dental procedures than urban residents. As such, rural residents might miss the opportunity to treat dental problems on time and their oral health would suffer. Racial/ethnic minority groups living in a more rural area had even more limited access to preventive dental care. These findings are additional evidence of disparities in dental service access between rural and urban communities. That is, minority groups in rural communities not only have limited access to dental care, they are also less likely to get the necessary preventive dental care even if they have accessed the dental care system. Innovative service delivery models that integrate tele-health21 and community-based case management43 may contribute to addressing these gaps in rural communities.

Contributor Information

Huabin Luo, Department of Public Health, Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Qiang Wu, Department of Biostatistics, College of Allied Health, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Ronny A. Bell, Department of Public Health, Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Wanda Wright, Department of Foundational Sciences, School of Dental Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Sara A. Quandt, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC.

Rashmita Basu, Department of Public Health, Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

Mark E. Moss, Department of Foundational Sciences, School of Dental Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) US Department of Health & Human Services. Second Quarter of Fiscal Year 2020 Designated HPSA Quarterly Summary. . 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caldwell JT, Lee H, Cagney KA. The Role of Primary Care for the Oral Health of Rural and Urban Older Adults. J Rural Health. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council (NRC). Improving access to oral health care for vulnerable and underserved populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/read/13116 . 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vargas CM, Dye BA, Hayes KL. Oral health status of rural adults in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(12):1672–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vargas CM, Ronzio CR, Hayes KL. Oral health status of children and adolescents by rural residence, United States. J Rural Health. 2003;19(3):260–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rural Health Research Center. Dentist Supply, Dental Care Utilization, and Oral Health among Rural and Urban US Residents. Report No.: 135. Available from: http://depts.washington.edu/uwrhrc/uploads/RHRC_FR135_Doescher.pdf. Accessed Feb 27,2020. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services. The 2004 Report to the Secretary: Rural Health and Human Service Issues. Available at: https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/rural/reportsrecommendations/2004-report-to-secretary.pdf. . 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skillman SM, Doescher MP, Mouradian WE, Brunson DK. The challenge to delivering oral health services in rural America. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70 Suppl 1(1):S49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman HS, Manski MC, Williams JN, Manski RJ. An analysis of preventive dental visits by provider type, 1996. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136(2):221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bader JD, Scurria MS, Shugars DA. Urban/rural differences in prosthetic dental service rates Journal of Rural Health. 1994;10(1):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janus C, Hunt RJ. Rural and urban differences in prosthodontic care provided by Virginia general dentists. Gen Dent. 2008;56(5):438–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agnecy for Healthcare Reasearch and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Available at: http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/survey_back.jsp. Accessed Feb 25,2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manski RJ, Macek MD, Brown E, Carper KV, Cohen LA, Vargas C. Dental service mix among working-age adults in the United States, 1999 and 2009. J Public Health Dent. 2014;74(2):102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohde F, Manski RJ, Macek MD. Dental Visit Utilization Procedures and Episodes of Treatment. J Am Coll Dent. 2016;83(2):28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen R, Davidson P. Improving access to care in America: Individual and contextual indicators. In: Andersen R, Rice T, Kominski J, eds. Changing the U.S. Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007:3–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of health and social behavior. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. MEPS-HC Summary Data Tables Technical Notes Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/hc_technical_notes.shtml. Accessed March 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Serv Res. 1998;33(3 Pt 1):571–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation/. Accessed March 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services. Improving oral health care services in rural America: Policy brief and recommendations. Available at: https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/rural/publications/2018-Oral-Health-Policy-Brief.pdf. Accessed Feb 27,2020. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniel SJ, Kumar S. Teledentistry: a key component in access to care. The journal of evidence-based dental practice. 2014;14 Suppl:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health Resources and Services Administration. Integration of Oral Health and Primary Care Practices. Rockville, MD; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: February 2014. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez TE, Galka AL, Lacy ES, Pellegrini AD, Sweier DG, Romito LM. Can midlevel dental providers be a benefit to the American public? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(2):892–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koppelman J, Vitzthum K, Simon L. Expanding Where Dental Therapists Can Practice Could Increase Americans' Access To Cost-Efficient Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(12):2200–2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VanWormer JJ, Tambe SR, Acharya A. Oral Health Literacy and Outcomes in Rural Wisconsin Adults. The Journal of rural health : official journal of the American Rural Health Association and the National Rural Health Care Association. 2019;35(1):12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Heft MW, Coward RT. Dental health attitudes among dentate black and white adults. Med Care. 1997;35(3):255–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arcury TA, Preisser JS, Gesler WM, Powers JM. Access to transportation and health care utilization in a rural region. The Journal of rural health : official journal of the American Rural Health Association and the National Rural Health Care Association. 2005;21(1):31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005;83(9):661–669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frisbee SJ, Chambers CB, Frisbee JC, Goodwill AG, Crout RJ. Association between dental hygiene, cardiovascular disease risk factors and systemic inflammation in rural adults. J Dent Hyg. 2010;84(4):177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tavares M, Lindefjeld Calabi KA, San Martin L. Systemic diseases and oral health. Dent Clin North Am. 2014;58(4):797–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Odell E, Kippenbrock T, Buron W, Narcisse M-R. Gaps in the primary care of rural and underserved populations: the impact of nurse practitioners in four Mississippi Delta states. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2013;25(12):659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doescher M Dentist Supply, Dental Care Utilization, and Oral Health Among Rural and Urban U.S. Residents. Available at: https://www.ruralhealthresearch.org/publications/970. Accessed Sept 09,2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woolfolk MW, Lang WP, Borgnakke WS, Taylor GW, Ronis DL, Nyquist LV. Determining dental checkup frequency. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 1999;130(5):715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manski RJ, Goodman HS, Reid BC, Macek MD. Dental insurance visits and expenditures among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):759–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chi DL, Leroux B. County-level determinants of dental utilization for Medicaid-enrolled children with chronic conditions: how does place affect use? Health Place. 2012;18(6):1422–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee W, Kim SJ, Albert JM, Nelson S. Community factors predicting dental care utilization among older adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(2):150–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;91(10):914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dye B, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla T. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011-2012. NCHS data brief. 2015(197):197–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colby S, Ortman J. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Available at: www.census.gov. Accessed May 10,2016. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dye BA, Weatherspoon DJ, Lopez Mitnik G. Tooth loss among older adults according to poverty status in the United States from 1999 through 2004 and 2009 through 2014. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2019;150(1):9–23.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arcury TA, Savoca MR, Anderson AM, et al. Dental care utilization among North Carolina rural older adults. J Public Health Dent. 2012;72(3):190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.James WL. All rural places are not created equal: revisiting the rural mortality penalty in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2122–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee H, Chalmers NI, Brow A, et al. Person-centered care model in dentistry. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]