Abstract

Objective:

The development of depressive symptoms in youth with IBD is a concerning disease complication, as higher levels of depressive symptoms have been associated with poorer quality of life and lower medication adherence. Previous research has examined the association between disease activity and depression, but few studies have examined individual differences in experience of stressful life events in relation to depressive symptoms. The purpose of the current study is to examine the relation between stressful life events and depression within pediatric IBD and to determine whether individual differences in stress response moderates this association.

Methods:

56 youth ages 8–17 years old diagnosed with IBD completed questionnaires about their depressive symptoms and history of stressful life events. We assessed skin conductance reactivity (SCR) to a stressful task as an index of psychophysiological reactivity.

Results:

Stressful life events (r = .36, p = .007) were positively related to depressive symptoms. Youth who demonstrated a greater maximum SC level during the IBD-specific stress trial compared to baseline (n=32) reported greater depressive symptoms. For these same participants, the relationship between stressful life events and depressive symptoms depended on SCR F(3, 28) = 4.23, p =.01, such that at moderate and high levels of SCR, a positive relationship between stressful life events and depressive symptoms was observed.

Conclusions:

The relationship between stressful life events and depressive symptoms in youth with IBD may depend on individual differences in processing stress, such that risk may increase with greater psychophysiological reactivity.

Keywords: depression, inflammatory bowel disease, psychophysiological reactivity, skin conductance, stressful life events, youth

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are a group of gastrointestinal diseases that include Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Individuals with IBD experience inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, which can cause abdominal pain, fever, fatigue, diarrhea, hematochezia, weight loss, and growth delays in youth1,2. An estimated 20–30% of individuals with IBD have an onset of symptoms before the age of 183,4.

Youth with IBD are at an increased risk for behavioral/emotional difficulties compared to healthy children, with clinically significant behavioral/emotional problems including depression affecting up to 31%5. In pediatric IBD, poorer psychosocial functioning including depression is associated with nonadherence, risk of relapse, worsened disease activity and higher health care costs6. Active disease has been shown to be associated with higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in one meta-analysis7. However, there is not a consistent exposure-response relationship between worsening disease activity and worsening depressive symptoms in youth with IBD5. Therefore, there is a need to identify additional factors that stratify patients in terms of risk for developing depressive symptoms. Existing work on correlates of symptoms of depression in pediatric IBD is limited and oftentimes outdated, though maternal depression8, steroid use9,10, stressful life events11, and domains of family functioning12 have been associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms cross-sectionally. More recent investigations have examined individual differences in cognitive or psychological constructs and how these self-reported factors are associated with depressive symptoms13–15. For example, Baudino and colleagues did not find a direct effect between disease activity and depressive symptoms but demonstrated that disease severity was associated with depressive symptoms via sequential indirect effects through parent and adolescent illness uncertainty14. Such nuanced studies that take individual differences into account will be critical for understanding the factors associated with increased depressive symptoms in youth with IBD.

The current study builds upon recent investigations of self-reported cognitive factors associated with depressive symptoms by examining individual differences in stress processing. Though not specific to IBD, direct or indirect exposure to a traumatic event places children at an increased risk of developing depressive symptoms through increased stress responsiveness16. Individual differences in stress processing can be measured experimentally to characterize the impact of stress exposure. Differences in stress processing, also known as physiological reactivity, broadly refer to bodily reactions in response to a stressor and vary in regards to intensity and threshold for activation between individuals. When presented with a stressor, such as a traumatic life event, sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity increases in preparation for managing the stressor17. Parasympathetic activity, in turn, facilitates recovery18. One widely recognized index of SNS activity is skin conductance (SC), which is based on electrodermal activity (electrical impulses on the surface of the skin) produced by sweat glands that are stimulated by the SNS19. In children, skin conductance reactivity (SCR) has demonstrated stability up to two years and across stressful tasks,20 suggesting that SCR has utility as a trait-like index of SNS reactivity. Higher psychophysiological reactivity is associated with internalizing symptoms in healthy samples20,21 and has been shown to amplify risk for negative psychosocial outcomes for children exposed to environmental stress21. Further, measures of psychophysiological reactivity including SC are elevated in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and have demonstrated reductions in reactivity following successful treatment for PTSD, suggesting that assessment of physiological reactivity offers an objective measure of pathological stress response22.

In adults with IBD, differences in SNS activity have been observed based on heart rate variability assessments. In one study, patients with ulcerative colitis, but not Crohn’s disease, demonstrated increased SNS activity,23 while in another study, patients with Crohn’s disease demonstrated higher SNS activity and lower parasympathetic activity compared to healthy controls24. Patients with UC have also demonstrated significantly lower parasympathetic function25. There is some evidence that individuals with IBD may process negative stimuli differently compared to individuals not diagnosed with IBD, with youth with IBD demonstrating an exaggerated pupil response to negative emotional words, suggesting that patients experience greater reactivity26.

The primary aim of the current study was to examine the relations between a history of stressful life events and symptoms of depression in youth newly diagnosed with IBD. Newly diagnosed patients were targeted for this study to avoid the potential confound of depressive symptoms that may result as a consequence of living with a chronic illness over time27. The second aim was to evaluate associations between psychophysiological reactivity, specifically SCR, history of stressful life events, and depressive symptoms. It was hypothesized that youth with IBD who experience more stressful life events would exhibit greater depressive symptoms and that SCR would moderate this relationship.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Considerations

All study procedures were in compliance with the Health Information Portability Accountability Act and were reviewed and approved by the Emory University School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board prior to study commencement. All participants provided informed consent for the study.

Participants

The current sample included 56 youth with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or indeterminate colitis and their parent or guardian. To participate, patients must have been: (a) diagnosed with biopsy-confirmed IBD within the last 45 days, (b) ages 8 through 17 years inclusive, (c) proficient in the English language, and (d) accompanied by at least one parent/guardian who was willing to participate. Patients who met any of the following criteria were excluded from participation: (a) previous diagnosis of severe intellectual disability and/or developmental disorder that impeded their ability to complete questionnaires and (b) had a parent who had an intellectual disability impeding the ability to complete questionnaires, (c) not proficient in the English language or (d) did not want to participate in the study.

Procedure

The current study was conducted at an outpatient pediatric gastroenterology clinic in the southeastern United States. Eligible participants were identified through upcoming scheduled appointments. Participants were initially recruited via telephone prior to their scheduled clinic visit and were informed of the study. Interested participants were given the option to participate on the same day of their clinic visit or during a follow-up research appointment. After informed parental consent and child assent were obtained, child and parent participants completed questionnaires via RedCap28 on iPads in the waiting room. Following questionnaire completion, trained research assistants brought child participants into a physical exam room where the child completed an assessment of physiological reactivity. Child participant SC was measured using the eSense system connected to an iPad. The eSense system is a portable method to measure autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity through SC (Mindfield ® Biosystems Ltd.). Velcro electrodes were attached to the second and third fingers of the non-dominant hand of the child participant using isotonic paste during a 10-minute conversation with the research assistant. Children completed a battery of tasks to assess physiological reactivity. Tasks relevant to the current manuscript include 1) a 90-second baseline assessment during which the child described activities (e.g., sports, hobbies) in which they like to partake, and 2) an IBD-specific stress induction trial during which the child described their most embarrassing or challenging experience since first having symptoms of IBD. The research assistant debriefed the child participant at the end of the assessment. Participants received a $25 Target gift card as compensation for their time.

Measures

Psychophysiological Reactivity

SC was measured using the eSense system connected to an iPad at a sampling rate of 10 Hz. SCR during the IBD-specific stress trial was calculated by subtracting minimum SC level during the baseline trial from maximum SC level during the IBD-specific stress trial. The resulting value was used as the psychophysiological reactivity index in subsequent analyses29.

Child Depressive Symptoms

Child depressive symptoms were measured using Children’s Depression Inventory 2 (CDI-230). The CDI-2 is a 28-item child-report measure of physiological, cognitive, behavioral, and emotional symptoms of depression. Each item contains three statements and children were asked to endorse one statement from each group of sentences that best applied to them (e.g., I am sad once in awhile; I am sad many times; I am sad all the time). Items are summed together to yield a total symptom severity score. Respondents’ answers are compared with age- and sex-based norms to obtain T-scores (M = 50, SD = 10). T-scores between 40–59 are considered “average,” between 60–64 “high average,” between 65–69 “elevated,” and ≥ 70 “very elevated.” Internal reliability of the CDI-2 was good in the current study (α = .89).

Child Exposure to Stressful Life Events

Children’s contextual risk due to lifetime exposure to traumatic events was assessed using The Lifetime Incidence of Traumatic Events – Student Form31. This is a 16-item measure of potential trauma and loss events and asks child respondents to indicate if he/she has ever experienced the target event (e.g., Did being in a car accident ever happen to you?). A total exposure score is obtained by summing the number of stressful life events endorsed.

Disease Severity

Information on date of diagnosis and IBD type was abstracted from medical records. Physician global assessment (PGA) ratings32 at the time of enrollment were available. The PGA is a global measure of patients’ disease severity routinely completed by the treating pediatric gastroenterologist. Physicians assess and rate patient’s disease activity based on objective (e.g., weight loss, lab tests, number of bloody stools) and subjective markers (e.g., abdominal pain, fatigue, abdominal tenderness) of disease. Markers of disease are not summed to create a total score; physicians assign a rating of quiescent (i.e., inactive), mild, moderate, or severe disease activity based on the patient’s global presentation. The PGA correlates with more complex measures of disease status used in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (e.g., Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI), Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI))33,34.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize the disease-related and psychological characteristics for the patient sample. SCR during the IBD-specific stress trial was calculated by subtracting minimum SC level during the baseline trial from maximum SC level during the IBD-specific stress trial. To determine whether the expected stress response was elicited, resulting SCR values were visually inspected to determine whether participants demonstrated a greater maximum SC level during the IBD-specific stress trial compared to their minimum SC value during the baseline trial. Pearson product moment correlations, t-tests, and one-way ANOVAs were conducted to determine whether any sociodemographic variables were related to variables of interest. Additionally, relations between psychophysiological reactivity (i.e., SCR), stressful life events, and depression were assessed using Pearson product moment correlations. Moderation by lifetime exposure to stress was modeled by regressing the interaction of lifetime exposure to stress and SCR during the stress task on depressive symptoms for participants who demonstrated the expected stress response (N = 32). Moderation examined the simple effects at high (+1 SD), medium (average) and low (−1 SD) levels of SCR following procedures of Hayes using the PROCESS macro35.

Results

Participants

The 56 participants ranged in age from 8 to 17 years (M age = 14.31, SD = 2.34) and included 45% males (n = 25). The majority of patients were diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (78%) and were rated as having mild disease (43%). At the time of participation, 43% of the sample was prescribed corticosteroids for treatment of IBD. Such a high proportion is likely since this sample was collected within 45 days of diagnosis. Additional demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Disease Characteristics of the Sample

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis Type | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 44 | 78 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 10 | 18 |

| Indeterminate colitis | 2 | 4 |

| Disease Activity (Physician Global Assessment)† | ||

| Quiescent | 21 | 38 |

| Mild | 24 | 43 |

| Moderate | 10 | 20 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White/Caucasian | 39 | 70 |

| Black/African American | 10 | 18 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 | 2 |

| Asian | 1 | 2 |

| Biracial | 2 | 4 |

| Missing | 3 | 6 |

| Family Income‡ | ||

| $10,000 to $49,999 | 7 | 13 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 12 | 21 |

| $75,000 to $99,000 | 7 | 13 |

| $100,000 to $124,999 | 9 | 16 |

| $125,000 to $149,999 | 6 | 11 |

| Above $150,000 | 11 | 20 |

| Missing/Chose not to respond | 4 | 7 |

Note. N = 56

Total does not sum to 56 as data is missing for 1 participant.

Percentages sum to 101 due to rounding.

Descriptive information of key study variables

It was expected that participants would demonstrate a greater maximum SC level during the IBD-specific stress trial compared to their minimum SC value during the baseline trial. Examination of the SCR data indicated that all participants did not demonstrate the expected response, suggesting a stress reaction during the IBD-specific stress trial may not have been elicited. Overall, thirty-two participants (57%) of the sample demonstrated the expected response. Exploratory analyses revealed that participants who demonstrated a greater SC level during the IBD-specific stress trials compared to their minimum baseline value reported significantly greater depression symptoms (M = 56.44, SD = 12.41) compared to participants who did not demonstrate the expected response, (M= 50.13, SD = 8.92), t(54) = 2.11, p = .04, d = 0.58. There was no difference in frequency of lifetime stressful events based on SCR during the stress trial. As the aim of including assessment of SC was to examine psychophysiological reactivity during an IBD-specific stress trial, only those participants demonstrating the expected response were included in subsequent analyses using the SCR variable. This decision is supported by past research in a pediatric illness sample in which only children who were considered “stressed” by the research protocol were used in follow-up analyses.36

Descriptive information for key study variables is found in Table 2. Within the total sample (N = 56), the majority of participants had depression symptoms within normal limits (79%), 5% had scores within the high average range, and 16% endorsed symptoms in the clinically elevated ranges. Among only those participants who demonstrated an expected stress response, 69% had depression symptoms within normal limits, 9% had scores within the high average range, and 22% endorsed symptoms in the clinically elevated ranges. Within the whole sample, the median number of lifetime stressful or traumatic events that participants endorsed was 3. Most commonly endorsed stressful life events included 1) someone in the family being very sick, hurt in the hospital, 2) family member dying, 3) having personally been in an accident, hurt, or sick in the hospital, 4) seeing someone else get hurt, and 5) parents separating or divorced.

Table 2.

Descriptive Information for Key Study Variables

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Observed Range | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stressful Life Eventsa | 2.98 | 2.00 | 0 – 10 | 56 |

| Depressionb | 53.73 | 11.40 | 40.00 – 87.00 | 56 |

| IBD Specific Stress Task | 2.24 | 2.16 | .04 – 7.82 | 32 |

Mean number of exposures endorsed

Mean displayed as T-score

Associations between sociodemographic variables and key study variables for the full sample were also examined. Child age was unrelated to depression symptoms, SCR, and lifetime stress exposure. Females (M T-score = 56.68, SD = 12.93) endorsed higher depression symptoms than males (M T-score = 50.08, SD = 7.98; t(54) = 2.23, p = .03, d = 0.61), but did not differ on other variables. Depression symptoms, SCR, and lifetime stress exposure did not differ based on child race, diagnosis, or PGA ratings, although lower family income was associated with more lifetime stress (r = −.27, p = .05). Corticosteroid prescription at the time of participation was not related to depression symptoms or SCR.

Results of correlations of primary study variables

Partial correlation analyses, controlling for child sex and family income, revealed a significant positive relationship between child report of stressful life events and greater depressive symptoms (r = .33, p = .02; see Table 2 for variable means). There was not a bivariate relationship between greater SCR during the IBD-specific stress trial and worse depressive symptoms using only those participants who demonstrated a positive stress response. PGA ratings were not correlated with depressive symptoms.

Results of moderation analyses

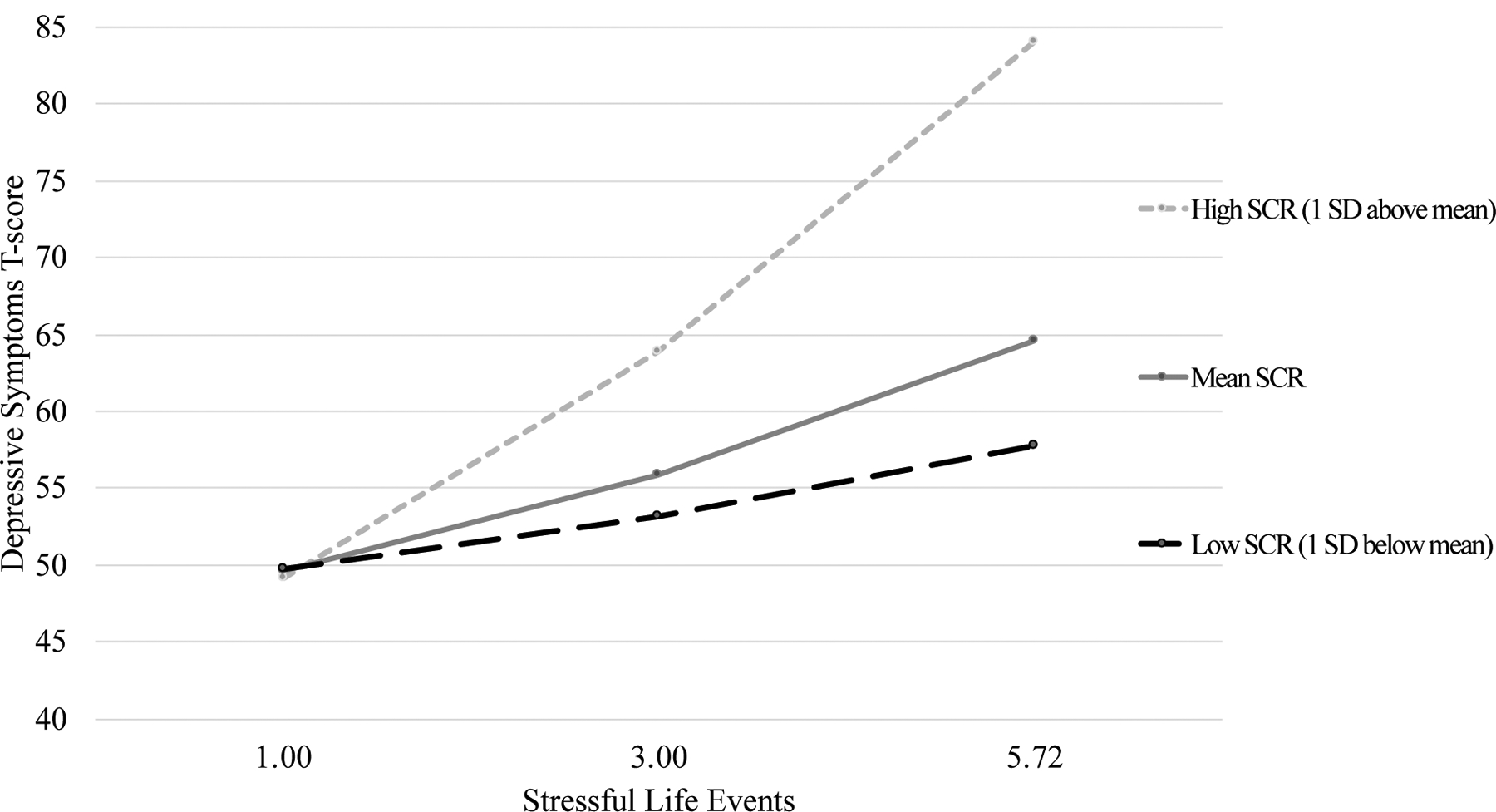

Within those participants who demonstrated the expected stress response (N = 32), regression analyses demonstrated an effect between stressful life events and youth depressive symptoms that varied based on SCR during the IBD-specific stress trial. At low levels of stressful life events, defined as one standard deviation below the mean count of stressful life events, depressive symptoms did not vary based on SCR (t = 1.72, p = .10). At mean levels of stressful life events within the sample, depressive symptoms varied based on SCR (t = 3.34, p = .002), with a mean depression T-score of 53.15 at low levels of SCR, 55.85 at moderate levels of SCR, and 63.90 at high levels of SCR. Similarly, at highest levels of stressful life events, defined as one standard deviation above the mean count of stressful life events, depressive symptoms varied based on SCR (t = 2.98, p = .006), with a mean depression T-score of 57.74 at low levels of SCR, 64.36 at moderate levels of SCR, and 84.03 at high levels of SCR. PGA ratings were not a significant covariate in the model and were therefore not included in the final model. See Table 3 for results of regression analyses of the interaction effect and Figure 1 for a graphical representation of results.

Table 3.

Stressful life events differentially associated with depressive symptoms: Regression model

| Youth Depressive Symptoms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba | SEBb | t | p | R2 | F | |

| Model | .312 | 4.23** | ||||

| Stressful Life Events (SLE) | 1.08 | 1.14 | .94 | .35 | ||

| Skin Conductance Reactivity during Stress Task | −1.49 | 1.58 | −.94 | .35 | ||

| Interaction: SLE x Skin Conductance Reactivity | 1.34 | .639 | 2.10 | .045 | ||

Note. N=32

B, unstandardized coefficients

SEB, standard error of unstandardized coefficients

p = .01

Figure 1.

Moderated effect of stressful life events on depressive symptoms at values of SCR during a stress task, n = 32

Discussion

Extant literature has suggested that youth with IBD are at higher risk of experiencing emotional functioning difficulties compared to their healthy peers37. Disease activity may partially account for increased symptoms of depression experienced by youth with IBD compared to peers38, but as this association is inconsistent, there is a need to identify factors beyond disease activity that are associated with depression in this patient population. Identifying factors associated with depression in pediatric patients with IBD is important for maximizing psychological as well as medical well-being, as depression has been associated with more barriers to adherence and less adherence to medical regimens39. The results from this study demonstrate a negative additive impact of high physiological reactivity on the relationship between stressful life events and depressive symptoms among youth with IBD. Prior research has demonstrated associations between cumulative environmental stressors such as stressful life events and depression in otherwise healthy youth40, but the current investigation is novel in simultaneously considering environmental stress as well as individual differences in physiological reactivity. Findings further support previous literature demonstrating higher depressive symptoms in chronically ill youth who have experienced more stressful or traumatic life events41.

Results suggest that youth with IBD who also endorse a greater number of stressful life events are more likely to report depressive symptoms, even early in the disease course. Additionally, for youth demonstrating the expected SC response to the stress trial, the relationship between stressful life events and depressive symptoms varied based on physiological reactivity as measured via SCR. Interestingly, at medium and high levels of reactivity, an increasingly strong relationship between higher number of stressful life events and greater depressive symptoms was observed. Further, greater depressive symptoms were reported by the youth who demonstrated the expected stress response. These results are consistent with past research in non-chronically ill youth demonstrating a relationship between greater sympathetic nervous system activity and internalizing symptoms (i.e., depression, anxiety)21. In a body of work conducted with youth exposed to marital conflict, El-Sheikh and colleagues (2005) found that physiological reactivity as measured via SCR placed children at greater risk for internalizing problems as conflict increased. Consideration of these findings along with ours suggests that psychophysiological reactivity serves as a between-individual difference associated with greater risk for internalizing pathology as reactivity increases.

The results of the current study build upon a consistent body of past research demonstrating the relationship between stressful life events and depressive symptoms in non-chronically ill samples42 and further support for similar associations in youth with IBD11. Diagnosis with a chronic illness is a stressor in and of itself, but these data demonstrate that even within diagnosed youth, experiencing a greater number of stressors across all domains of life may be associated with greater risk for depressive symptoms. Moreover, the most frequently endorsed stressors in the current sample (i.e., someone in the family was in the hospital after getting hurt or sick, someone in the family died, child got hurt in an accident or was sick in the hospital, parents separated or divorced, child saw someone else get hurt) are all relatively common stressors that occur across childhood, indicating that even everyday stressors, as compared to severely traumatic events (e.g., abuse), may still lead to higher symptoms of depression. Similar to past research demonstrating an increasing, graded association between adverse childhood experiences and poor health outcomes43, we observed worse depressive scores as the quantity of stressful life events increased. In addition to these commonly endorsed life stressors, youth with IBD face challenges specific to their illness including disease symptoms, hospitalizations, and missed school due to appointments and infusions. Consequently, youth with IBD may deplete emotional coping resources more quickly compared to their peers who are not managing stressors associated with a chronic illness, leading to at least one possible pathway to increased depressive symptoms compared to healthy peers.

Despite the strengths of the study, there are limitations to consider. First, the sample size was relatively small and all participants were recruited from a single gastroenterology center, which may limit generalizability. Regarding measurement of SCR, all participants did not demonstrate the expected increase in SC level during the stress trial compared to baseline, suggesting a stress reaction during the IBD-specific stress trial may not have been elicited. We hypothesize that the acclimation period prior to the baseline task was not adequately long to account for the novelty of having the eSense sensors attached to participants’ fingers. In future research, we intend to have a longer acclimation period prior to baseline measurement to allow for participants to return to a true baseline prior to starting the stress task. It is also possible that the IBD-specific stress task was not adequately stressful and that future studies should alter the tasks or provide a subjective rating of stress to determine if a response is being elicited. In a recent qualitative study of pediatric patients diagnosed with IBD, the majority of patients reportedly expressed relief at the time of diagnosis for an explanation for their symptoms, and the children indicated that the diagnosis “had a limited negative impact on their day-to-day life.”44 In light of these findings, it may be that the IBD-specific stress task was not particularly stressful for participants. However, higher rates of depressive symptoms in patients who demonstrated the expected stress response suggest that there may be individual differences at least partially determining whether a patient responded with the expected increase in SC level during the stress trial. Future research should consider whether patients who demonstrated the expected increase in SC level during the stress trial differ in additional self-reported individual difference factors that have demonstrated relevance to depressive symptoms in pediatric IBD patients (e.g., illness uncertainty14, illness stigma, and thwarted belongingness15). The current study did not model or control for symptoms of anxiety or state stress. Future research should assess symptoms of anxiety or internalizing symptoms transdiagnostically in addition to taking into account state stress levels to more fully characterize the likely complex relationships between internalizing symptoms, state stress, and physiological reactivity. The current study calculated SCR based on subtracting minimum SC level during the baseline trial from maximum SC level during the IBD-specific stress trial. Future research may consider estimating participants’ baseline SC using an average value to increase reliability. The use of child-report of stressful life events and depressive symptoms may have resulted in reporter bias, so future studies may wish to include multi-informant reports such as caregivers or diagnostic interviews. Our study did not observe a relationship between PGA ratings and depressive symptoms, though disease activity has been found to be related to emotional functioning in previous studies10. It seems possible that the relationship between disease severity and depressive symptoms may develop over time, explaining why such a relationship was not observed in this newly diagnosed sample. Lastly, a cross-sectional design was used, which limits findings to a correlational interpretation and does not allow for causality. Future studies should consider a longitudinal design to determine whether stressful life events and physiological reactivity precede depression symptoms.

The lack of a non-IBD control group prohibits conclusions regarding specificity of findings to patients diagnosed with IBD. That being said, we suspect that findings are likely not specific to youth with IBD given findings of higher depressive symptoms in other chronic illness samples who have experienced more stressful or traumatic life events41 and findings of positive relationships between psychophysiological reactivity and internalizing symptoms in healthy samples21,45. However, youth with IBD are a particularly interesting patient sample to examine the relationships between stressful life events, differences in psychophysiological reactivity, and depression, given that IBD is increasingly recognized as a product of the brain-gut axis and its psycho-neuro-immune interactions46. The relationships between stress, depression, and disease symptoms are understudied in pediatric samples, but in adult IBD samples there is increasingly sophisticated research on the bidirectional relationships among these constructs. In adults with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission followed prospectively for 1 year, short-term stress at the last visit before relapse was predictive for the risk of clinical relapse (measured using the Clinical Colitis Activity Index47), whereas depression, baseline long-term stress, and baseline mucosal healing were not predictive48. In adults with IBD assessed at months 0, 3, and 6, bidirectional relationships between perceived stress and changes in symptom activity were observed, whereas no relationship between perceived stress and change in intestinal inflammation as assessed by fecal calprotectin was observed49. Such findings highlight the need for studies designed to identify mechanisms underlying the relationship between stress and disease outcomes for patients affected by IBD in addition to studies that include objective measures of disease activity, such as fecal calprotectin, in addition to clinical symptoms.

Future investigations should test whether SCR, or other measures of physiological reactivity such as heart rate variability, can be used to prospectively identify patients with IBD at risk for emotional and behavioral functioning difficulties. If so, there may be a potential for intervening on sympathetic arousal with the goal of positive downstream effects on psychological symptoms. In addition, future research with larger samples should consider inclusion of symptoms of anxiety in addition to depressive symptoms to discern whether symptom specificity exists in associations with stressful life events and physiological reactivity. Mental health services for youth are limited, typically reactionary as opposed to preventative, and oftentimes costly for families in terms of time, effort, and money. Biomarkers of psychological risk are urgently needed to most effectively allocate resources and prevent additional suffering in our most vulnerable populations, including youth diagnosed with IBD and other chronic illnesses.

Highlights.

Stressful life events and depressive symptoms pediatric inflammatory bowel disease

Greater skin conductance reactivity associated with greater depressive symptoms

Skin conductance reactivity moderates stressful life events and depressive symptoms

Psychophysiological reactivity associated with pediatric depressive symptoms

Source of Funding:

This research was supported by The Digestive Disease Research Fund at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002378 and KL2TR002381, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23DK122115.

Acronyms:

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel diseases

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- UC

ulcerative colitis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest: None

References

- 1.Diefenbach KA, Breuer CK. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG. 2006;12(20):3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackner LM, Sisson DP, Crandall WV. Review: Psychosocial issues in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2004;29(4):243–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malaty HM, Fan X, Opekun AR, Thibodeaux C, Ferry GD. Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among children: A 12-year study. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2010;50(1):27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawczenko A, Sandhu BK, Logan RF, et al. Prospective survey of childhood inflammatory bowel disease in the British Isles. Lancet. 2001;357(9262):1093–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed-Knight B, Mackner LM, Crandall WV. Psychological aspects of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents In: Mamula P, Grossman AB, Baldassano RN, Kelsen JR, Markowitz JE, eds. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. 3rd ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hommel KA, Greenley RN, Maddux MH, Gray WN, Mackner LM. Self-management in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: A clinical report of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2013;57(2):250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stapersma L, van den Brink G, Szigethy EM, Escher JC, Utens E. Systematic review with meta-analysis: anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2018;48(5):496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke PM, Neigut D, Kocoshis S, Sauer J, Chandra R. Correlates of depression in new onset pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 1994;24(4):275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mrakotsky C, Bousvaros A, Chriki L, et al. Impact of acute steroid treatment on memory, executive function, and mood in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2005;41(4):540–541. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szigethy E, Levy-Warren A, Whitton S, et al. Depressive symptoms and inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2004;39(4):395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke PM, Kocoshis SA, Chandra R, Whiteway M, Sauer J. Determinants of depression in recent onset pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29(4):608–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuman SL, Graef DM, Janicke DM, Gray WN, Hommel KA. An exploration of family problem-solving and affective involvement as moderators between disease severity and depressive symptoms in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20(4):488–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamwell KL, Baudino MN, Bakula DM, et al. Perceived Illness Stigma, Thwarted Belongingness, and Depressive Symptoms in Youth With Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2018;24(5):960–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baudino MN, Gamwell KL, Roberts CM, et al. Disease Severity and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Mediating Role of Parent and Youth Illness Uncertainty. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2019;44(4):490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts CM, Gamwell KL, Baudino MN, et al. The Contributions of Illness Stigma, Health Communication Difficulties, and Thwarted Belongingness to Depressive Symptoms in Youth with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2020;45(1):81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: Preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1023–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chida Y, Hamer M. Chronic Psychosocial Factors and Acute Physiological Responses to Laboratory-Induced Stress in Healthy Populations: A Quantitative Review of 30 Years of Investigations. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134(6):829–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labanski A, Langhorst J, Engler H, Elsenbruch S. Stress and the brain-gut axis in functional and chronic-inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases: A transdisciplinary challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;111:104501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings EM, El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Keller PS. Children’s skin conductance reactivity as a mechanism of risk in the context of parental depressive symptoms. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2007;48(5):436–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Sheikh M Children’s skin conductance level and reactivity: are these measures stable over time and across tasks? Developmental psychobiology. 2007;49(2):180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Sheikh M The role of emotional responses and physiological reactivity in the marital conflict-child functioning link. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(11):1191–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin MG, Resick PA, Galovski TE. Does physiologic response to loud tones change following cognitive-behavioral treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder? J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(1):25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganguli SC, Kamath MV, Redmond K, et al. A comparison of autonomic function in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and in healthy controls. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(12):961–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pellissier S, Dantzer C, Canini F, Mathieu N, Bonaz B. Psychological adjustment and autonomic disturbances in inflammatory bowel diseases and irritable bowel syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(5):653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma P, Makharia GK, Ahuja V, Dwivedi SN, Deepak KK. Autonomic dysfunctions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in clinical remission. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(4):853–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones NP, Siegle GJ, Proud L, et al. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease and high-dose steroid exposure on pupillary responses to negative information in pediatric depression. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(2):151–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: an updated meta-analysis. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2010;36(4):375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinrichs R, Michopoulos V, Winters S, et al. Mobile assessment of heightened skin conductance in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2017;34:502–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovacs M Children’s Depression Inventory 2 (CDI 2). 2nd ed. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenwald R, Rubin A. Brief assessment of children’s post-traumatic symptoms: Development and preliminary validation of parent and child scales. Research on Social Work Practice. 1999;9:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crandall W, Kappelman MD, Colletti RB, et al. ImproveCareNow: the development of a pediatric inflammatory bowel disease improvement network. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17(1):450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, et al. Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn’s disease activity index. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 1991;12(4):449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kappelman MD, Crandall WV, Colletti RB, et al. Short pediatric Crohn’s disease activity index for quality improvement and observational research. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011;17(1):112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes A Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 1 ed New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McQuaid E, Fritz G, Nassau J, Lilly ML, Mansell A, Klein RB. Stress and airway resistance in children with asthma. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2000;49:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenley RN, Hommel KA, Nebel J, et al. A meta-analytic review of the psychosocial adjustment of youth with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2010;35(8):857–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szigethy E, Whitton SW, Levy-Warren A, DeMaso DR, Weisz J, Beardslee WR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: A pilot study. Journal of Amer Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(12):1469–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Treatment adherence in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: The collective impact of barriers to adherence and anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2012;37(3):282–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH Jr. Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental psychology. 2001;37(3):404–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walders-Abramson N, Venditti EM, Ievers-Landis CE, et al. Relationships among Stressful Life Events and Physiological Markers, Treatment Adherence, and Psychosocial Functioning among Youth with Type 2 Diabetes. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;165(3):504–508.e501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammen C Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH, Anda RF. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37(3):268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kluthe C, Isaac DM, Hiller K, et al. Qualitative Analysis of Pediatric Patient and Caregiver Perspectives After Recent Diagnosis With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raine A, Venables PH, Williams M. Relationships between central and autonomic measures of arousal at age 15 years and criminality at age 24 years. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47(11):1003–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonaz BL, Bernstein CN. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):36–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rachmilewitz D Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. British Medical Journal. 1989;298(6666):82–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langhorst J, Hofstetter A, Wolfe F, Hauser W. Short-term stress, but not mucosal healing nor depression was predictive for the risk of relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis: a prospective 12-month follow-up study. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2013;19(11):2380–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sexton KA, Walker JR, Graff LA, et al. Evidence of Bidirectional Associations Between Perceived Stress and Symptom Activity: A Prospective Longitudinal Investigation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2017;23(3):473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]