Abstract

In the last decade, large-scale genomic studies in patients with hematologic malignancies identified recurrent somatic alterations in epigenetic modifier genes. Among these, the de novo DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A has emerged as one of the most frequently mutated genes in adult myeloid as well as lymphoid malignancies and in clonal hematopoiesis. In this review, we discuss recent advances in our understanding of the biochemical and structural consequences of DNMT3A mutations on DNA methylation catalysis and binding interactions and summarize their effects on epigenetic patterns and gene expression changes implicated in the pathogenesis of hematologic malignancies. We then review the role played by mutant DNMT3A in clonal hematopoiesis, accompanied by its effect on immune cell function and inflammatory responses. Finally, we discuss how this knowledge informs therapeutic approaches for hematologic malignancies with mutant DNMT3A.

Keywords: Epigenetics, DNMT3A, DNMT3A R882 mutation, DNA methylation, hematologic cancers, myeloid malignancies, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), clonal hematopoiesis (CH), Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome (TBRS), hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal and differentiation, gene expression, inflammation, cancer therapy

Since the discovery of recurrent DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) a decade ago (1–3) the role of DNMT3A defects in hematologic malignancies has been a subject of intense investigation. In subsequent studies, DNMT3A alterations were identified at various frequencies in multiple myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms, often associated with poor prognosis, yet were virtually absent outside of the blood system (3–6). Mechanistic and functional studies established a role for DNMT3A in enforcing a tight balance between the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) differentiation and self-renewal, through the maintenance of specific DNA methylation profiles that control gene expression programs (7–10). Patterns of co-occurrence with other leukemia-associated genetic lesions and evidence from pre-single-cell, bulk sequencing studies aiming to reconstruct clonal architecture implicated DNMT3A mutations as an early, pre-leukemic event (11–14). This was later confirmed by detection of mutant DNMT3A in non-malignant, pre-leukemic HSCs isolated from AML patients (15), and culminated in the discovery of frequent somatic DNMT3A mutations in age-related clonal hematopoiesis (CH) (16–19). At the same time, de novo mutations in DNMT3A were detected in individuals with a recently described Tatton-Brown-Rahman overgrowth and intellectual disability syndrome (20). Studies into the molecular mechanisms of these phenotypes effected by DNMT3A alterations, mostly believed to be loss-of-function, supplied a wealth of granular methylomic data including evidence of erosion of the DNA methylation canyons and explored cross-talk with other layers of epigenetic regulation (21–25). These early advances are already summarized in a number of excellent reviews (26–28). Since then, there were a plethora of studies in two key areas. First, structural determinants of DNMT3A binding specificity to DNA and chromatin, as well as protein-protein interactions. Second, the involvement of DNMT3A in hematopoietic lineage fate determination during differentiation, and its central role in clonal hematopoiesis, regulation of inflammatory states and immune cell function. These recent advances, as well as emerging therapeutic approaches for hematologic conditions with mutant DNMT3A, are the main focus of this review.

DNMT3A structure and regulation of catalysis

DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) is a 130kDa protein encoded by the DNMT3A gene spanning 23 exons on human chromosome 2 (or chromosome 12 in the mouse). It is expressed as two alternatively spliced isoforms: the ubiquitous DNMT3A1 (long), and DNMT3A2 (short), detected in the embryonic stem cells (ESCs), early embryonic tissues, as well as testes, ovaries, spleen and thymus. The long isoform contains extra amino acids that enhance anchoring to nucleosomes and binding to DNA in vitro (29–31).

Domain structure of mammalian DNMTs, also reviewed elsewhere (32–35), comprises the N-terminal regulatory part consisting of the PWWP and the ADD domains that promotes nuclear localization of the enzyme, targeting to chromatin and interactions with allosteric regulators, and the C-terminal domain that is mainly involved in DNA binding and methylation catalysis.

The Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro (PWWP) domain is required for targeting to tri- and especially dimethylated histone H3 lysine 36 (H3K36) marking gene bodies and intergenic regions respectively (36,37). Binding to these marks allosterically increases the methyltransferase activity of DNMT3A and thus protect these genomic regions from spurious transcription initiation (38,39). Conversely, phosphorylation by CK2 reduces DNMT3A activity while targeting it to heterochromatic regions (40). The ATRX-DNMT3L-DNMT3A (ADD) domain binds to unmethylated H3K4 that marks inactive chromatin, and allosterically releases the autoinhibition of the enzymatic activity of DNMT3A (41). The ADD domain additionally interacts with epigenetic factors involved in transcriptional gene silencing such as Polycomb Repressive Complex (PRC) 2 catalytic subunit EZH2, H3K9-specific histone methyltransferase SUV39H1, and histone-lysine deacetylase HDAC1, and with transcription factors p53, PU.1 and MYC (42,43). Conversely, a recent study in mouse neurons showed the interaction of the methylated DNA binding protein MeCP2 with the ADD domain causes autoinhibition of the catalytic activity of DNMT3A (44).

The highly conserved catalytic domain of DNMT3A catalyzes 5’-cytosine methylation within CpG dinucleotides using S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) as a methyl donor. Unlike the highly related enzyme DNMT3B that methylates multiple adjacent CpG sites processively through a non-cooperative mechanism (45), DNMT3A forms large multimeric protein/DNA complexes with itself or other DNMT3s necessary for cooperative binding and efficient distributive catalysis (46). Most characterized is a heterotetrameric complex composed of a DNMT3A homodimer bound by two non-catalytic stimulatory DNMT3L subunits in a 3L-3A-3A-3L structure (47,48). The DNMT3A-DNMT3A dimerization interface is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions between the phenylalanine residues, while the DNMT3A-DNMT3L interface is mediated by salt bridges and hydrogen bonding interactions. Two DNMT3A monomers co-methylate two adjacent CpG sites separated by 14bp within the same DNA duplex (49). DNMT3B is also essential to the activity of DNMT3A, especially in the absence of DNMT3L (47,50,51).

DNMT3A mutations and their functional consequences

Somatic mutations in DNMT3A found in hematological malignancies are distributed throughout the open reading frame and generally fall into one of the following categories. First, nonsense, frameshift (splice and indel), and missense alterations in key residues, which are consistent with a loss-of-function. Second, a specific hotspot point mutation at arginine 882 (R882) at the dimerization interface, most often converted to histidine or cytosine. Finally, variants of unknown significance (VUS), single amino acid substitutions with only sparse biochemical characterization. De novo germline or rare inherited mutations found in Tatton-Brown-Rahman overgrowth and intellectual disability syndrome (TBRS) have been shown to follow a similar distribution (20,27,52–54). The R882 mutations are believed to have a dominant negative effect on the methyltransferase activity due to impaired oligomerization, although this notion is debated (55). Structural efforts found the R882 residue stabilizes the target recognition domain (TRD) through H-bonding within the DNA binding domain. Consequently, R882 substitutions lead to defective DNA binding and impaired TRD-loop-mediated CpG recognition (49,56,57). This results in focal hypomethylation at specific loci that usually include developmental genes, resulting in increased HSC self-renewal and reduced differentiation, eventually driving leukemogenesis (28,58).

Interestingly, the conformational change in the TRD loop of DNMT3AR882H resulted in an altered flanking sequence preference at positions +1, +2, and +3 that resembles the DNA substrates usually favored by DNMT3B (57,59,60). Consistently, DNMT3AR882-specific hypermethylation of such DNMT3A/DNMT3B chimeric substrates (61) can be detected in primary AML samples along with hypomethylation of disfavored sequences, both of which are associated with a unique subset of genes (62), implying a gain-of-function effect (60). On the other hand, tetramerization interface mutations R736H and R771G or an internal W893S substitution exhibit a preference to methylating cytosines at non-CpG positions in vitro (63), which cannot be maintained at DNA replication, and has also been observed for R882H (57).

In addition to multimerization and binding to DNA, other binding interactions can be affected by DNMT3A mutations. Examples include an increased interaction of DNMT3AG543C with histone H3 (1) and of DNMT3AR882H with the PRC1 components (64). Conversely, DNMT3AR882 exhibited decreased binding to HDAC1 and 2, and haploinsufficient loss of DNMT3A was associated with a gain of H3K27ac histone acetylation and increased expression of PD-L1 in a TF-1 cell line model (65). Moreover, whereas a tumor suppressor p53 can compete with DNMT3L for binding at the tetramer interface and inhibit catalytic activity of wild-type DNMT3A, R882H allosterically relieves such negative regulation (63).

The PWWP domain preferentially targets DNMT3A to H3K36me2 and to a lesser extent to H3K36me3 (36). Loss of H3K36me2 marks resulting from NSD1 haploinsufficiency leads to decreased DNA methylation observed in Sotos syndrome (66) and tracks closely with TBRS (67). Conversely, de novo missense mutations in the PWWP domain that do not impair protein stability, W330R or D333N, were identified in patients with microcephalic dwarfism (68). Mouse models (W326R or D329A) demonstrated a postnatal growth delay due to loss of interaction with H3K36me2/me3 and progressive hypermethylation of H3K27me3-marked bivalent chromatin and of DNA methylation canyons. This gain-of-function phenotype led to a transcriptional imbalance between key developmental genes, resulting in premature neuronal differentiation, impaired self-renewal, and growth retardation (68,69).

The clinical and molecular overlap between overgrowth and intellectual disability syndromes caused by inactivating mutations in DNMT3A (Tatton-Brown-Rahman), NSD1 (Sotos), PRC2 catalytic subunit EZH2 (Weaver), as well as SETD2 (Luscan-Lumish) and histone H1 (Rahman) highlight the molecular relationship between different layers of epigenetic regulation and chromatin. Disruption of these genes, characterized by shared yet unique DNA methylation landscapes (70), is inextricably related to hematologic malignancies. Further studies into the complexities of this crosstalk will be vital to our understanding of the DNMT3A-mutant-driven pathology.

DNA methylation and gene expression studies

DNMT3A mutations are now commonly considered preleukemic events, yet the consensus over their effects on DNA methylation landscapes and gene expression programs only recently emerged, due in part to the differences between model systems. Studies of complete hematopoietic-specific Dnmt3a loss in mice found hypomethylation of HSC-related genes that resulted in enhanced stem-cell self-renewal at the expense of differentiation (7,8,10), even when other co-operating genetic lesions were present (22,71–74). This leads to competitive advantage over normal HSCs and may predispose to the acquisition of cooperating proleukemogenic mutations in the expanded clone. Partial Dnmt3a loss or point mutations produced more subtle phenotypes such as focal hypomethylation of specific CpGs (24) with modest changes to global DNA methylation and transcriptional activity of genes nearest to differentially methylated regions (DMRs). This was observed in the HSCs from both leukemic and non-leukemic primary samples with DNMT3AR882H, suggesting that hypomethylation predates the onset of leukemia (23).

Studies focusing on the most common DNMT3AR882 hot-spot mutation found in AML or its mouse counterpart Dnmt3aR878H reported less consistent and highly context-specific phenotypes, which included focal hypomethylation at enhancer regions and undermethylated canyon edges, particularly at SMAD3 and NFκB binding motifs (62). This was occasionally associated with increased expression of HSC-related, Hoxa cluster, Meis1 (75), and Mycn genes (25), although negative enrichment of MYC and E2F target gene signatures was also reported in a variety of contexts (62,71,76). In addition, activation of mTOR and AML signaling pathways (77), and deregulation of cell cycle-related gene signatures such as G2M checkpoint (71,76) were identified. Downregulation of differentiation-associated genes (Cepba, Cepbe and Pu.1) as a consequence of aberrant DNMT3AR882 interaction with the PRC1 complex at target loci was also proposed (64). Overall, DNMT3AR882 resulted in deregulation of transcriptional programs related to cell identity and normal hematopoietic function, which may contribute to leukemogenesis (71).

Among these studies of hematopoiesis with altered DNMT3A, hypomethylation of active hematopoietic lineage-specific enhancers (10,22,62,71–73,78) as well as erosion at the DNA methylation canyon edges (21,22) emerged as a unifying theme that could be extended to both lymphoid and myeloid malignancies with various co-mutational contexts, and even non-hematopoietic tissues (79). Consistently, in a T-ALL model driven by Dnmt3a–/– combined with Flt3ITD, hypomethylated enhancers were enriched for active histone marks H3K27ac and H3K4me1 (71). In Dnmt3a knock-out with neomorphic Idh2R140Q this was accompanied by an increase in repressive H3K9me3 marks exacerbating the differentiation block (74). The DNA methylation and gene expression changes along with myeloid skewing could be partially restored upon re-expression of wild-type Dnmt3a, demonstrating that these phenotypes are reversible (72,80).

In recent years, numerous RNA-seq studies supplied growing evidence for Dnmt3a involvement in megakaryocyte-erythroid differentiation and immune cell function, supporting previous more laborious phenotypic and functional observations (10,81). Leukemia-initiating cells from Dnmt3a–/–:Idh2R140Q or Dnmt3a–/–:Tet2–/– double knock-out mice have a megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor immunophenotype and repress corresponding gene expression programs (22,74). Single-cell multi-omics studies in Dnmt3a–/– HSCs showed skewed transcriptional priming towards erythroid over myelomonocytic lineage. This was due to hypomethylation and higher accessibility of the CpG-rich erythroid transcription factor motifs (82). In a T-ALL model driven by Dnmt3a–/– and constitutively active Notch1, enhancer regions showed profound hypomethylation, while gene sets associated with myeloid cell function, inflammation and immune responses were upregulated (78). Cooperating Dnmt3a–/–:Jak2V617F in a model of myelofibrosis (MF) led to increased DNA accessibility at active enhancers driving activation of proinflammatory Tnfα/Nfκb signaling pathways for a fully penetrant myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) (73). Gene networks related to mast cell degranulation and activation were enriched in the Dnmt3a–/– cells (83). In innate immunity, Dnmt3a regulates the production of type 1 interferons by maintaining the expression of HDAC9 in macrophages (84), while DNMT3A-mediated hypermethylation redirects differentiation of primary monocytes from dendritic cells (DCs) towards cancer tolerogenic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (85).

Epigenetic, gene expression, and functional changes observed in various models with Dnmt3a alterations are summarized in Table 1, along with cooperating genetic interactions in hematologic malignancies.

Table 1.

Molecular and phenotypic consequences of DNMT3A alterations and cooperating mutations in human disease and in animal models.

| Cooperating mutations in patients with DNMT3A-mutant disease | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperating mutation | DNMT3A mutation type(s) | Malignancy (AML / MDS / MF / lymphoid) | Comments & references | |

| FLT3-ITD | More likely R882 | Adult AML* | DNMT3A, FLT3-ITD, NPM1 mutations often co-occur (11,93,133–135) | |

| NPM1 | More likely R882 | AML | NPM1 is often acquired after DNMT3A mutation (11,87,89,90,93,134) | |

| FLT3-ITD and NPM1 | AML | DNMT3A, NPM1, and FLT3 mutations strongly co-occur, predict aggressive disease (11,135) | ||

| IDH1/2 | Truncating | AML, MDS and other | Predicts poor survival (11,74,93,94,134) | |

| TET2 | T-cell lymphomas, MDS, AML | (88,134,136,137) | ||

| JAK2 | MPN, MF | (98) | ||

| NOTCH1 | Non-R882 | T-ALL, ETP-ALL | (78,138) | |

| RUNX1 | AML, rarely MDS | Reduced survival, older age, poor treatment response (139–142) | ||

| KMT2A-PTD (MLL-PTD) | Enriched, mostly R882 | AML | Poor survival (143,144); mutually exclusive with MLL translocations in previous studies (98) | |

| RAD21, STAG2, SMC3 (cohesin complex) | DNMT3A mutations may offset the survival disadvantage of SMC3-haploinsufficient cells (11,134,145,146) | |||

| 7q deletion | AML, MPN, MDS | DNMT3A mutations often ancestral (147); in MDS, often preceded by −7/del(7q) (148) | ||

| 5q deletion | MDS, or MPN | (149) | ||

| 9q deletion | AML | Del(9q) as sole cytogenetic abnormality; strong co-association with NPM1 mutation, FLT3-ITD rare (150) | ||

| DNMT3A and cooperating mutations in in vitro and animal in vivo models | ||||

| DNMT3A alteration | Cooperating mutation(s) | Malignancy or disease phenotype | Epigenetic changes | Gene expression and functional changes |

| Dnmt3a−/− | N/A | Myeloid malignancies | Altered methylation patterns, focal loss of methylation at regulatory regions (8) | Upregulation of stemness genes and repression of differentiation factors (8), myeloid skewing (80) |

| Dnmt3a−/− | Tet2−/− | CMML and lymphoid malignancy | Hypomethylation of HSC-related gene enhancers | Activation of HSC genes, lineage-specific transcription factors, erythroid differentiation, JAK-STAT pathway (22) |

| Idh2R140Q | MDS, AML, and lymphoma | Gain of H3K9me3 and loss of H3K9ac (74) | Megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor phenotype in leukemia-initiating cells | |

| Flt3ITD | T-ALL | Profound hypomethylation at gene enhancers and canyon edges | Increased expression of inflammation, immune response, HSC- and myeloid-related genes, decreased expression of mature T cells genes (71) | |

| Activated Notch1 signaling, through NICD expression | T-ALL | Enhancer and exon hypomethylation | Repression of pro-apoptotic genes, increased expression of myeloid, inflammation and immune response genes (78) | |

| Jak2V617F | MPN/MF | Enhancer hypomethylation | Proinflammatory signaling, HSC gene expression (73) | |

| Dnmt3a+/− | Flt3ITD | AML, MPN | Modest changes in overall methylation. Hypomethylation at hematopoietic enhancers and canyon edges (71,72). HSPC-like methylation in leukemic blasts | Increased expression of genes involved in cell fate specification (71) Enrichment for HSPC genes, genes downregulated during myeloid development, and c-Myc target genes (72) |

| DNMT3AR882H/+ (human) or Dnmt3aR878H/+ (mouse) | Tet2−/− | T-ALL, T cell lymphomas, MPN and AML (88,136) | Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and local hypomethylation Notch pathway genes | Repression of tumor suppressor genes and Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Activation of Notch pathway genes (151) |

| Nras | AML | Focal hypomethylation at gene regulatory elements and gain of histone acetylation | Activation of stemness genes of the Meis1-Mn1-Hoxa node (25) | |

| Idh2R140Q | AML | Loss of differential methylation at enhancers, other regulatory regions | Activation of Ras signaling and apoptosis, repression of Myc targets and heme metabolism (62) | |

| Flt3ITD | AML | Hypomethylation of gene enhancers | Repression of Myc, E2f and G2M checkpoint genes, upregulation of homeobox genes (71) | |

| N/A | AML | Focal hypomethylation at distal regulatory elements such as at canyon shores, enhancers and undermethylated canyons (25), Attenuated CpG island hypermethylation (23) | Modest gene expression changes (23). Upregulation of stemness genes, HoxA cluster and Meis1 (75), negative enrichment of G2M checkpoint genes (71,76). Downregulation of differentiation genes, Cepba, Cepbe, Pu.1 (64) | |

| DNMT3AW330R, DNMT3AD333N (gain-of-function) and mouse models Dnmt3aW326R, Dnmt3aD329A | Microcephalic dwarfism, delayed growth | Hypermethylation at polycomb-marked DNA methylation valleys, loss of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 bivalent chromatin at developmental genes (68) | Increased expression of neurogenic genes at the expense of pluripotency genes in mESCs differentiated into neurons in vitro (68,69) | |

| DNMT3AW297del (mouse W293del), DNMT3AI310N (mouse I306N), DNMT3AY365C | TBRS (overgrowth syndrome) | Hypomethylation at intergenic regions and decreased binding to H3K36me2 | Aberrant chromatin localization and NSD1-DNMT3A crosstalk (36) | |

DNMT3A and cooperating mutations in hematologic malignancies

DNMT3A mutations tend to be an early event in hematologic malignancies that requires additional genetic lesions, summarized in Table 1. The spectrum of cooperating mutations is non-random and varies considerably between diseases. For example, FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3ITD) and mutations in NPM1 are most frequent in AML, while TET2 mutations are found in both myeloid and lymphoid malignancies (11,72,76,86–88). Furthermore, DNMT3A mutations are almost exclusive to adult leukemia; the rare DNMT3A-positive pediatric AML cases are likely associated with TBRS (52).

More detailed studies revealed distinct clinical and molecular implications associated with different DNMT3A mutation types and allelic dosage. DNMT3AR882 were more prevalent in the context of NPM1 (89,90) and FLT3ITD (91,92) mutations, more likely to be ancestral or “founder” event, and also associated with shorter overall survival (28,93). By contrast, IDH1 mutations tended to co-occur with truncating DNMT3A mutations (74,93,94), while non-R882 DNMT3A mutations were predominant in ALL (78,95) where they were frequently biallelic (4,5) and associated with older age, treatment resistance, and poor outcome (96). In comparison, in myeloid malignancies mutations in DNMT3A are usually heterozygous (3). Genetic modeling in mice provided further evidence for the critical role of Dnmt3a dosage. In combination with Flt3ITD, homozygous ablation of Dnmt3a was more likely to result in T-ALL, while loss of a single Dnmt3a allele led to AML (71,72). Dnmt3a knockout in combination with Idh1 mutation (74) or Tet2 knockout (22) synergistically induce myeloid malignancies in animals. Similarly, cooperating mutations in cKit (97) and Kras (8) in Dnmt3a–/– HSCs drive malignant transformation. While these studies provided invaluable insights into the mechanisms of mutational cooperativity in leukemia pathogenesis, the genetic makeup and disease phenotype observed in the clinic was only partially recapitulated. There is a growing interest in creating clinically-accurate mouse models with the ultimate goal to empower therapeutic and drug development efforts. A Dnmt3aR878H:Flt3ITD:Npm1c triple-mutant mouse that faithfully models an aggressive AML (11) enabled the discovery of a novel therapeutic resistance mechanism driven by altered chromatin regulation (76).

Furthermore, the temporal order of mutations influences clinical disease presentation. Studies in DNMT3A-mutated MPNs driven by JAK2 or MPL alterations found that “DNMT3Amut-first” patients had essential thrombocythemia (ET), while “JAK2-first” patients were younger and more likely to present with polycythemia vera (PV) or MF (98). A recent study took these concepts one step further and modeled sequential acquisition of Dnmt3aR878H and Npm1cA mutations in mice, with varying latency between these genetic events. Dnmt3aR878H produced an expansion of the HSC compartment (analogous to CH in humans) (76,77) that progressed to myeloproliferation/myelodysplasia after Npm1cA and, with additional selective pressures of proliferative and/or pro-inflammatory stress, to AML (15,86). Increasing the latency between Dnmt3a and the “second hit” mutation renders a more fulminant disease. Further reports unveiling the contributing cell-autonomous and cell-extrinsic mechanisms are eagerly awaited.

The strong requirement for cooperating oncogenic events highlights the role of mutant DNMT3A as an early event that facilitates leukemic transformation by other mechanisms rather than driving it per se. This pre-malignant role is well in alignment with its high prevalence in CH, discussed next.

DNMT3A mutations in clonal hematopoiesis

Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) is a clonal expansion of HSCs in the absence of hematologic disease; it is commonly detected by the presence of somatic mutations, often in presumed leukemia driver genes such as in DNMT3A. Incidence of CH sharply increases with age, spurring the term “age related clonal hematopoiesis” (ARCH). CH was first described in the 1990s based on increased X-inactivation skewing in women with age (99). More recently, modern sequencing technologies facilitated detection of sizeable hematopoietic clones (variant allele frequency (VAF) >2%) in >30% of people aged 60+ (16–18,100). Mutations in DNMT3A are by far the most common genetic event associated with CH (up to 40% of all CH cases). DNMT3A-driven CH was associated with prior environmental exposures including radiation, tobacco use and iatrogenic interventions, although the causal relationship between these factors and initial acquisition of mutations or expansion of the mutant clone has not been established.

Since Dnmt3a–/– mice demonstrate enhanced HSC self-renewal (7,8), it is possible that in CH DNMT3A mutations potentially compensate for aging-related HSC exhaustion (101). Conversely, it may provide the “first hit” towards leukemic transformation (102). Individuals with CH have a 0.5–1% chance per year to develop hematologic cancer, compared to <0.1% without CH. Yet, DNMT3A lesions predict only a moderately elevated risk of leukemic progression, in contrast to other common mutations such as in TP53 (103,104). In line with these observations, in a lymphoblastoid cell line from a mosaic individual with DNMT3AR771Q/+-driven CH, stereotypical erosion of DNA methylation within regulatory regions of stem cell self-renewal and cancer-related genes, and not mutational frequency, favored clonal dominance and establishment of a cancer-poised epigenomic landscape (105). While these studies provide a rationale for expanded screening for CH to identify individuals at an increased risk of leukemia, the clinically-meaningful clone size and the cost-benefit ratio of monitoring are debated. A pivotal study modeling progression of Dnmt3a-driven CH to MPN and ultimately AML in mice suggested that a shift towards expansion of the myeloid-restricted progenitors of the mutant clone may serve as an early biomarker (86). Additional studies are critically needed to improve our understanding of the molecular and clinical implications of DNMT3A mutations in CH leading to better patient stratification algorithms.

Importantly, clinical observations from large cohorts unselected for hematologic disease revealed a strong relationship of CH with other comorbidities and increased all-cause mortality. While clonally expanded HSCs appear functionally normal and give rise to mature, differentiated immune cell lineages that permeate nearly all tissues outside of the hematological compartment, presence of CH mutations is likely to effect subtle changes in their function and, by extension, impact the physiology of surrounding tissues. Thus, CH is strongly associated with incidence and severity of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (106), corroborated in a mouse model of CH driven by Dnmt3a loss (107). In a model of CH driven by CRISPR-mediated Dnmt3a loss, mature myeloid cells accentuated inflammation and exacerbated the extent of experimental atherosclerosis through increased secretion of a cluster of chemokines and cytokines (108). These results establish a causal role of DNMT3A-driven CH in CVD pathogenesis as well as other conditions with a prominent inflammatory component (109) including aplastic anemia (110) and solid tumors (111). In the latter study, presence of CH was associated with inferior overall survival due to progression of the primary malignancy. This suggests that CH can impact cancer pathophysiology through non-tumor-cell-autonomous mechanisms. Studies showed elevated inflammatory leukocytes and inflammation-related cytokines in the serum of colitis patients with DNMT3A-associated CH (112). Similar findings were reported in activated macrophages and mast cells after DNMT3A loss, which increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-6 and CXCL13 (83). On the other hand, inflammation signaling associated with aged bone marrow microenvironment contributed to CH through accentuated TNFα signaling and IFNγ response that primed the Dnmt3a-mutant HSCs and promoted their clonal expansion (113). Furthermore, cell extrinsic environmental factors such as bacterial infections bestow a fitness advantage to Dnmt3a-mutant hematopoietic clones (114). Additional studies exploring the link between DNMT3A mutations, CH, inflammation, and immune responses could yield many new exciting insights with biological and translational implications.

Therapeutic implications

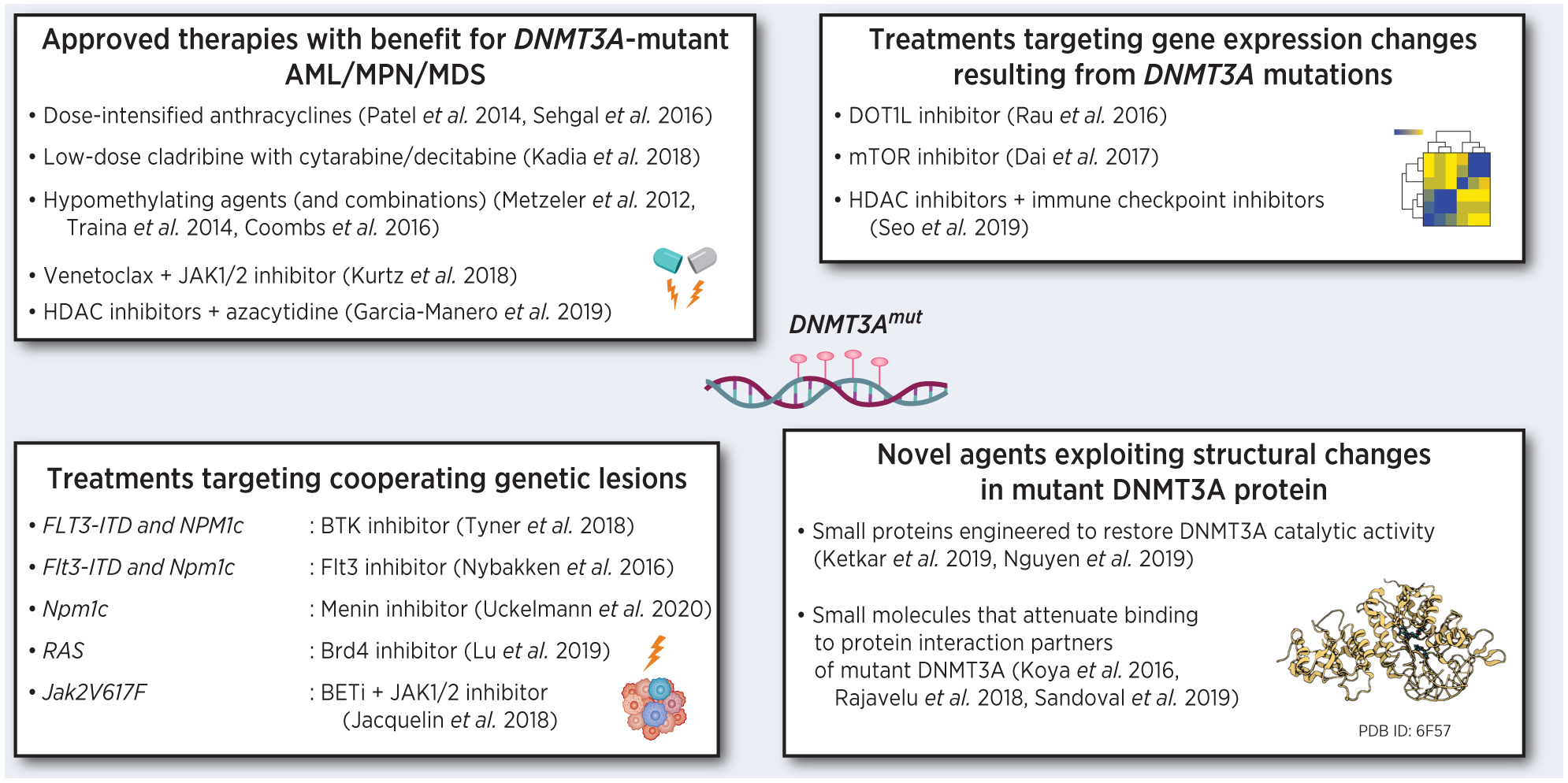

The high frequency of DNMT3A mutations in myeloid neoplasms (about a quarter of AML and ~10% of MPN and MDS cases), its truncal, or early, timing in tumor evolution, and the association with increased risk of relapse and poor overall prognosis position DNMT3A alterations and their molecular consequences as an attractive therapeutic target. Yet, despite significant advances in the understanding of the molecular pathophysiology of DNMT3A-mutant disease, the need for satisfactory treatment approaches that balance efficacy and toxicity remains unmet. To date, therapy development efforts have focused in four main areas (Figure 1): a) validate and fine-tune existing combinations already approved for AML, MPN, or MDS; b) inhibit aberrantly activated signaling pathways; c) target co-occuring actionable mutations and their downstream consequences; and d) exploit structural changes in the mutant DNMT3A protein.

Figure 1.

Emerging therapeutic approaches for myeloid malignancies with DNMT3A mutations. Images created with BioRender.com.

In AML clinical trials, adverse outcomes bestowed by DNMT3A mutations could be improved by dose-intensified anthracyclines during induction, suggesting that cells with mutant DNMT3A are less sensitive to these agents (115,116). A follow-up study in a model of Dnmt3a-mutant hematopoiesis revealed that the relative resistance to anthracyclines was due to abnormal chromatin remodeling and impaired DNA damage sensing (76). As a significant proportion of patients with DNMT3A-positive AML fall into the advanced age category with frequent co-morbidities, the increased toxicity and treatment-related mortality of dose-dense anthracyclines may not be acceptable, necessitating less aggressive treatment strategies. A low intensity regimen of nucleoside analogs cladribine combined with alternating cytarabine and decitabine can be an acceptable treatment option for older AML patients that particularly benefits those with DNMT3A mutations (117). Mechanistically, cells expressing mutant DNMT3A treated with cytarabine had a defect in replication fork restart leading to persistent replication stress and accumulation of unrepaired DNA damage (118). Hypomethylating agents (HMAs) such as azacytidine and decitabine are the backbone of the low-intensity regimens for AML and MDS. These cytidine analogs are incorporated into DNA and function as covalent suicide inhibitors of DNMTs and as DNA damage inducers by forming bulky adducts. Small clinical studies reported favorable responses in AML and MDS with DNMT3A mutations (119–121). This seemingly counterintuitive observation may be explained by the altered flanking sequence preference of the mutant DNMT3A enzyme that causes aberrant hypermethylation at non-canonical gene loci, or by defects in DNA damage response in the presence of mutant DNMT3A protein. Thus, bone marrow cells from mice expressing Dnmt3aR878H readily underwent differentiation after decitabine exposure, while Dnmt3a–/– bone marrow accumulated immature cKit+ cells (122). Further research is needed to shed light on the mechanistic and therapeutic implications of different types of DNMT3A mutations. Furthermore, combinations of HMAs with other targeted agents have shown promise in patients with DNMT3A mutations (123).

Patterns of co-mutation may help guide targeted treatment strategies for DNMT3A-mutant disease. A landmark integrative precision oncology Beat AML trial found a strong correlation between FLT3-ITD, NPM1, and DNMT3A mutational triad and sensitivity to ibrutinib, a BTK and TEC inhibitor FDA-approved for the treatment of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (124). The FLT3 inhibitor AC220/quizartinib was shown to preferentially elicit a differentiation response in the triple-mutant AML; in contrast, DNMT3A mutations were rare in patients with cytotoxic responses (125). In another ex vivo study, primary AML cells harboring DNMT3A mutations were slightly more sensitive to the JAK1/2 kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib plus venetoclax (an inhibitor of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 protein) combination, independently from FLT3 and NPM1 status (126).

Treatments targeting gene expression or methylation changes associated with DNMT3A mutations are also gaining traction. Several studies identified upregulation of the homeobox cluster A and B (HOXA/B) genes, which promote HSC self-renewal and are associated with poor prognosis in AML (1,64,75). Small molecule inhibitors of the histone methyltransferase DOT1L restored repression of the HOXA/B genes both in vitro and in vivo, and proved effective for DNMT3A mutant leukemia (127). The mTOR pathway, another regulator of the HOX gene expression, was found to be activated in the DNMT3A-mutant context. mTOR inhibitor rapamycin was effective against cells with DNMT3A mutations in vitro (77); it will be important to validate its therapeutic potential in preclinical models. DNMT3A mutations co-occur with NPM1c mutations in the preleukemic setting (60–80%) and in AML. Npm1c:Dnmt3aR878H double-mutant mice exhibited increased self-renewal in myeloid progenitor cells, associated with further activation of HoxA/B genes and Meis1. A menin inhibitor VTP-50469, previously shown to disrupt critical gene expression networks in NPM1-mutant AML cell line (128), was effective in eradicating pre-leukemic progenitors and preventing progression to AML in this model (129).

Bromodomain inhibitors, specifically an inhibitor of the histone acetylation reader BRD4, was effective in a study of AML with concurrent DNMT3AR882 and RAS mutations, in both in vitro and in vivo models. Pharmacological inhibition of BRD4 suppressed a subset of aberrantly activated gene targets that likely contribute to leukemogenesis, consistent with increased H3K27ac levels in TF-1 cells (130). In a model of myelofibrosis, loss of Dnmt3a in hematopoietic cells expressing Jak2V617F resulted in high expression of TNFα via NFκB pathway accompanied by increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Combining BET inhibitors with JAK1/2 kinase inhibitors could have therapeutic relevance (73).

Strategies related to engineering small proteins to restore the full catalytic activity of mutant DNMT3A or the ability of wild-type DNMT3A to heterotetramerize by disrupting the wildtype-mutant binding interface, have also been proposed and could potentially offer therapeutic benefit (56,80). With better understanding of the protein-protein binding repertoire of mutant DNMT3A such as p53, MeCP2, TDGs and PRC1, pharmacologic interventions to attenuate these interactions may open additional therapeutic avenues to combat DNMT3A mutant AML (44,63,64).

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

While mutations in DNMT3A are found in malignancies of virtually every hematopoietic lineage, the molecular understanding of its impact on malignant transformation is only beginning to emerge. Recent biochemical, structural, and -omics studies have shed light on the nature of aberrant methylation patterns, crosstalk with other layers of epigenetic regulation, and subsequent changes in gene expression profiles that contribute to clonal expansion and promote leukemogenesis. Further refinement and unification of our knowledge of these programs, including in the various co-mutational contexts that define disease subtypes and/or clonal architecture (28,131,132), are expected to translate into more effective therapies for patients with DNMT3A-mutant AML and other malignancies.

Recent years saw an explosion of research into the role of DNMT3A mutations in CH and its comorbidities. Abundant evidence supports accentuated self-renewal creating an expanded pool of cancer-poised HSCs, yet the definitive factors effecting malignant transformation await to be discovered. Once identified, these will be game-changing for CH prognostication and preventative interventions. Additionally, cells with DNMT3A mutations propagate an inflammatory microenvironment leading to positive feedback to mutant clone self-renewal and proliferation and may exacerbate other non-hematologic disease conditions such as CVD. Characterizing the cell extrinsic and intrinsic factors and the mechanisms that promote the inception of CH in the DNMT3A-mutant context is crucial to the development of therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R00CA178191 and R01DK121831) and the Thomas H. Maren Junior Investigator Fund (University of Florida) to O.A.G.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yan XJ, Xu J, Gu ZH, Pan CM, Lu G, Shen Y, et al. Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia. Nat Genet 2011;43:309–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamashita Y, Yuan J, Suetake I, Suzuki H, Ishikawa Y, Choi YL, et al. Array-based genomic resequencing of human leukemia. Oncogene 2010;29:3723–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, McLellan MD, Lamprecht T, Larson DE, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2424–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roller A, Grossmann V, Bacher U, Poetzinger F, Weissmann S, Nadarajah N, et al. Landmark analysis of DNMT3A mutations in hematological malignancies. Leukemia 2013;27:1573–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grossmann V, Haferlach C, Weissmann S, Roller A, Schindela S, Poetzinger F, et al. The molecular profile of adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: mutations in RUNX1 and DNMT3A are associated with poor prognosis in T-ALL. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2013;52:410–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribeiro AF, Pratcorona M, Erpelinck-Verschueren C, Rockova V, Sanders M, Abbas S, et al. Mutant DNMT3A: a marker of poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2012;119:5824–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Challen GA, Sun D, Jeong M, Luo M, Jelinek J, Berg JS, et al. Dnmt3a is essential for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Nat Genet 2011;44:23–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong M, Park HJ, Celik H, Ostrander EL, Reyes JM, Guzman A, et al. Loss of Dnmt3a Immortalizes Hematopoietic Stem Cells In Vivo. Cell Reports 2018;23:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayle A, Yang L, Rodriguez B, Zhou T, Chang E, Curry CV, et al. Dnmt3a loss predisposes murine hematopoietic stem cells to malignant transformation. Blood 2015;125:629–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guryanova OA, Lieu YK, Garrett-Bakelman FE, Spitzer B, Glass JL, Shank K, et al. Dnmt3a regulates myeloproliferation and liver-specific expansion of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Leukemia 2016;30:1133–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Roberts ND, et al. Genomic Classification and Prognosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2209–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, Miller CA, Larson DE, Koboldt DC, et al. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell 2012;150:264–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corces-Zimmerman MR, Hong WJ, Weissman IL, Medeiros BC, Majeti R. Preleukemic mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia affect epigenetic regulators and persist in remission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:2548–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jan M, Snyder TM, Corces-Zimmerman MR, Vyas P, Weissman IL, Quake SR, et al. Clonal evolution of preleukemic hematopoietic stem cells precedes human acute myeloid leukemia. Science translational medicine 2012;4:149ra18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shlush LI, Zandi S, Mitchell A, Chen WC, Brandwein JM, Gupta V, et al. Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature 2014;506:328–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, Manning A, Grauman PV, Mar BG, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine 2014;371:2488–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, McLellan MD, Johnson KJ, Wendl MC, et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nature Medicine 2014;20:1472–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genovese G, Kähler AK, Handsaker RE, Lindberg J, Rose SA, Bakhoum SF, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. New England Journal of Medicine 2014;371:2477–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKerrell T, Park N, Moreno T, Grove CS, Ponstingl H, Stephens J, et al. Leukemia-associated somatic mutations drive distinct patterns of age-related clonal hemopoiesis. Cell Rep 2015;10:1239–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatton-Brown K, Seal S, Ruark E, Harmer J, Ramsay E, Del Vecchio Duarte S, et al. Mutations in the DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A cause an overgrowth syndrome with intellectual disability. Nat Genet 2014;46:385–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeong M, Sun D, Luo M, Huang Y, Challen GA, Rodriguez B, et al. Large conserved domains of low DNA methylation maintained by Dnmt3a. Nat Genet 2014;46:17–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Su J, Jeong M, Ko M, Huang Y, Park HJ, et al. DNMT3A and TET2 compete and cooperate to repress lineage-specific transcription factors in hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Genet 2016;48:1014–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spencer DH, Russler-Germain DA, Ketkar S, Helton NM, Lamprecht TL, Fulton RS, et al. CpG Island Hypermethylation Mediated by DNMT3A Is a Consequence of AML Progression. Cell 2017;168:801–16.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russler-Germain DA, Spencer DH, Young MA, Lamprecht TL, Miller CA, Fulton R, et al. The R882H DNMT3A mutation associated with AML dominantly inhibits wild-type DNMT3A by blocking its ability to form active tetramers. Cancer cell 2014;25:442–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu R, Wang P, Parton T, Zhou Y, Chrysovergis K, Rockowitz S, et al. Epigenetic Perturbations by Arg882-Mutated DNMT3A Potentiate Aberrant Stem Cell Gene-Expression Program and Acute Leukemia Development. Cancer Cell 2016;30:92–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang L, Rau R, Goodell MA. DNMT3A in haematological malignancies. Nature reviews Cancer 2015;15:152–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunetti L, Gundry MC, Goodell MA. DNMT3A in Leukemia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2017;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudry SF, Chevassut TJ. Epigenetic Guardian: A Review of the DNA Methyltransferase DNMT3A in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia and Clonal Haematopoiesis. Biomed Res Int 2017;2017:5473197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson KD, Uzvolgyi E, Liang G, Talmadge C, Sumegi J, Gonzales FA, et al. The human DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) 1, 3a and 3b: coordinate mRNA expression in normal tissues and overexpression in tumors. Nucleic Acids Res 1999;27:2291–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen T, Ueda Y, Xie S, Li E. A novel Dnmt3a isoform produced from an alternative promoter localizes to euchromatin and its expression correlates with active de novo methylation. J Biol Chem 2002;277:38746–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suetake I, Mishima Y, Kimura H, Lee YH, Goto Y, Takeshima H, et al. Characterization of DNA-binding activity in the N-terminal domain of the DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a. Biochem J 2011;437:141–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jurkowska RZ, Jurkowski TP, Jeltsch A. Structure and function of mammalian DNA methyltransferases. Chembiochem 2011;12:206–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ravichandran M, Jurkowska RZ, Jurkowski TP. Target specificity of mammalian DNA methylation and demethylation machinery. Org Biomol Chem 2018;16:1419–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyko F The DNA methyltransferase family: a versatile toolkit for epigenetic regulation. Nat Rev Genet 2018;19:81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenberg MVC, Bourc’his D. The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019;20:590–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinberg DN, Papillon-Cavanagh S, Chen H, Yue Y, Chen X, Rajagopalan KN, et al. The histone mark H3K36me2 recruits DNMT3A and shapes the intergenic DNA methylation landscape. Nature 2019;573:281–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu W, Li J, Rong B, Zhao B, Wang M, Dai R, et al. DNMT3A reads and connects histone H3K36me2 to DNA methylation. Protein Cell 2020;11:150–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren W, Gao L, Song J. Structural Basis of DNMT1 and DNMT3A-Mediated DNA Methylation. Genes (Basel) 2018;9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neri F, Rapelli S, Krepelova A, Incarnato D, Parlato C, Basile G, et al. Intragenic DNA methylation prevents spurious transcription initiation. Nature 2017;543:72–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deplus R, Blanchon L, Rajavelu A, Boukaba A, Defrance M, Luciani J, et al. Regulation of DNA methylation patterns by CK2-mediated phosphorylation of Dnmt3a. Cell Rep 2014;8:743–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo X, Wang L, Li J, Ding Z, Xiao J, Yin X, et al. Structural insight into autoinhibition and histone H3-induced activation of DNMT3A. Nature 2015;517:640–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen BF, Chan WY. The de novo DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A in development and cancer. Epigenetics 2014;9:669–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emran AA, Chatterjee A, Rodger EJ, Tiffen JC, Gallagher SJ, Eccles MR, et al. Targeting DNA Methylation and EZH2 Activity to Overcome Melanoma Resistance to Immunotherapy. Trends Immunol 2019;40:328–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajavelu A, Lungu C, Emperle M, Dukatz M, Bröhm A, Broche J, et al. Chromatin-dependent allosteric regulation of DNMT3A activity by MeCP2. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:9044–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norvil AB, Petell CJ, Alabdi L, Wu L, Rossie S, Gowher H. Dnmt3b Methylates DNA by a Noncooperative Mechanism, and Its Activity Is Unaffected by Manipulations at the Predicted Dimer Interface. Biochemistry 2018;57:4312–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajavelu A, Jurkowska RZ, Fritz J, Jeltsch A. Function and disruption of DNA methyltransferase 3a cooperative DNA binding and nucleoprotein filament formation. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:569–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jurkowska RZ, Rajavelu A, Anspach N, Urbanke C, Jankevicius G, Ragozin S, et al. Oligomerization and binding of the Dnmt3a DNA methyltransferase to parallel DNA molecules: heterochromatic localization and role of Dnmt3L. J Biol Chem 2011;286:24200–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jia D, Jurkowska RZ, Zhang X, Jeltsch A, Cheng X. Structure of Dnmt3a bound to Dnmt3L suggests a model for de novo DNA methylation. Nature 2007;449:248–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang ZM, Lu R, Wang P, Yu Y, Chen D, Gao L, et al. Structural basis for DNMT3A-mediated de novo DNA methylation. Nature 2018;554:387–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veland N, Lu Y, Hardikar S, Gaddis S, Zeng Y, Liu B, et al. DNMT3L facilitates DNA methylation partly by maintaining DNMT3A stability in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:152–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duymich CE, Charlet J, Yang X, Jones PA, Liang G. DNMT3B isoforms without catalytic activity stimulate gene body methylation as accessory proteins in somatic cells. Nat Commun 2016;7:11453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hollink IHIM, van den Ouweland AMW, Beverloo HB, Arentsen-Peters STCJ, Zwaan CM, Wagner A. Acute myeloid leukaemia in a case with Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome: the peculiar. J Med Genet 2017;54:805–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lemire G, Gauthier J, Soucy JF, Delrue MA. A case of familial transmission of the newly described DNMT3A-Overgrowth Syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2017;173:1887–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tenorio J, Alarcón P, Arias P, Dapía I, García-Miñaur S, Palomares Bralo M, et al. Further delineation of neuropsychiatric findings in Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome due to disease-causing variants in DNMT3A: seven new patients. Eur J Hum Genet 2020;28:469–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emperle M, Dukatz M, Kunert S, Holzer K, Rajavelu A, Jurkowska RZ, et al. The DNMT3A R882H mutation does not cause dominant negative effects in purified mixed DNMT3A/R882H complexes. Sci Rep 2018;8:13242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen TV, Yao S, Wang Y, Rolfe A, Selvaraj A, Darman R, et al. The R882H DNMT3A hot spot mutation stabilizes the formation of large DNMT3A oligomers with low DNA methyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem 2019;294:16966–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anteneh H, Fang J, Song J. Structural basis for impairment of DNA methylation by the DNMT3A R882H mutation. Nat Commun 2020;11:2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim SJ, Zhao H, Hardikar S, Singh AK, Goodell MA, Chen T. A DNMT3A mutation common in AML exhibits dominant-negative effects in murine ES cells. Blood 2013;122:4086–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Norvil AB, AlAbdi L, Liu B, Tu YH, Forstoffer NE, Michie AR, et al. The acute myeloid leukemia variant DNMT3A Arg882His is a DNMT3B-like enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:3761–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Emperle M, Adam S, Kunert S, Dukatz M, Baude A, Plass C, et al. Mutations of R882 change flanking sequence preferences of the DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A and cellular methylation patterns. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:11355–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Emperle M, Rajavelu A, Kunert S, Arimondo PB, Reinhardt R, Jurkowska RZ, et al. The DNMT3A R882H mutant displays altered flanking sequence preferences. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:3130–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glass JL, Hassane D, Wouters BJ, Kunimoto H, Avellino R, Garrett-Bakelman FE, et al. Epigenetic Identity in AML Depends on Disruption of Nonpromoter Regulatory Elements and Is Affected by Antagonistic Effects of Mutations in Epigenetic Modifiers. Cancer discovery 2017;7:868–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sandoval JE, Huang YH, Muise A, Goodell MA, Reich NO. Mutations in the DNMT3A DNA methyltransferase in acute myeloid leukemia patients cause both loss and gain of function and differential regulation by protein partners. J Biol Chem 2019;294:4898–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koya J, Kataoka K, Sato T, Bando M, Kato Y, Tsuruta-Kishino T, et al. DNMT3A R882 mutants interact with polycomb proteins to block haematopoietic stem and leukaemic cell differentiation. Nat Commun 2016;7:10924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seo J, Li L, Small D. Dissociation of the DNMT3A-HDAC1 Repressor Complex Induces PD-L1 Expression. Blood 2019;134:3759- [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choufani S, Cytrynbaum C, Chung BH, Turinsky AL, Grafodatskaya D, Chen YA, et al. NSD1 mutations generate a genome-wide DNA methylation signature. Nat Commun 2015;6:10207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tatton-Brown K, Loveday C, Yost S, Clarke M, Ramsay E, Zachariou A, et al. Mutations in Epigenetic Regulation Genes Are a Major Cause of Overgrowth with Intellectual Disability. Am J Hum Genet 2017;100:725–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heyn P, Logan CV, Fluteau A, Challis RC, Auchynnikava T, Martin CA, et al. Gain-of-function DNMT3A mutations cause microcephalic dwarfism and hypermethylation of Polycomb-regulated regions. Nat Genet 2019;51:96–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sendžikaitė G, Hanna CW, Stewart-Morgan KR, Ivanova E, Kelsey G. A DNMT3A PWWP mutation leads to methylation of bivalent chromatin and growth retardation in mice. Nat Commun 2019;10:1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Choufani S, Gibson WT, Turinsky AL, Chung BHY, Wang T, Garg K, et al. DNA Methylation Signature for EZH2 Functionally Classifies Sequence Variants in Three PRC2 Complex Genes. Am J Hum Genet 2020;106:596–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang L, Rodriguez B, Mayle A, Park HJ, Lin X, Luo M, et al. DNMT3A Loss Drives Enhancer Hypomethylation in FLT3-ITD-Associated Leukemias. Cancer Cell 2016;29:922–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meyer SE, Qin T, Muench DE, Masuda K, Venkatasubramanian M, Orr E, et al. DNMT3A Haploinsufficiency Transforms FLT3ITD Myeloproliferative Disease into a Rapid, Spontaneous, and Fully Penetrant Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer discovery 2016;6:501–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jacquelin S, Straube J, Cooper L, Vu T, Song A, Bywater M, et al. Jak2V617F and Dnmt3a loss cooperate to induce myelofibrosis through activated enhancer-driven inflammation. Blood 2018;132:2707–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang X, Wang X, Wang XQD, Su J, Putluri N, Zhou T, et al. Dnmt3a loss and Idh2 neomorphic mutations mutually potentiate malignant hematopoiesis. Blood 2020;135:845–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferreira HJ, Heyn H, Vizoso M, Moutinho C, Vidal E, Gomez A, et al. DNMT3A mutations mediate the epigenetic reactivation of the leukemogenic factor MEIS1 in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene 2016;35:3079–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guryanova OA, Shank K, Spitzer B, Luciani L, Koche RP, Garrett-Bakelman FE, et al. DNMT3A mutations promote anthracycline resistance in acute myeloid leukemia via impaired nucleosome remodeling. Nat Med 2016;22:1488–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dai YJ, Wang YY, Huang JY, Xia L, Shi XD, Xu J, et al. Conditional knockin of Dnmt3a R878H initiates acute myeloid leukemia with mTOR pathway involvement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:5237–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kramer AC, Kothari A, Wilson WC, Celik H, Nikitas J, Mallaney C, et al. Dnmt3a regulates T-cell development and suppresses T-ALL transformation. Leukemia 2017;31:2479–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rinaldi L, Datta D, Serrat J, Morey L, Solanas G, Avgustinova A, et al. Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b Associate with Enhancers to Regulate Human Epidermal Stem Cell Homeostasis. Cell Stem Cell 2016;19:491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ketkar S, Verdoni AM, Smith AM, Bangert CV, Leight ER, Chen DY, et al. Remethylation of. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:3123–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Verdoni AM, Cole CB, Klco JM, Ley TJ. DNMT3A R882H Overexpression Leads To Hematopoietic and Skin Alterations In Transgenic Mice. Blood 2013;122:479- [Google Scholar]

- 82.Izzo F, Lee SC, Poran A, Chaligne R, Gaiti F, Gross B, et al. DNA methylation disruption reshapes the hematopoietic differentiation landscape. Nat Genet 2020;52:378–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leoni C, Montagner S, Rinaldi A, Bertoni F, Polletti S, Balestrieri C, et al. Dnmt3a restrains mast cell inflammatory responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017;114:E1490–E9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li X, Zhang Q, Ding Y, Liu Y, Zhao D, Zhao K, et al. Methyltransferase Dnmt3a upregulates HDAC9 to deacetylate the kinase TBK1 for activation of antiviral innate immunity. Nat Immunol 2016;17:806–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rodríguez-Ubreva J, Català-Moll F, Obermajer N, Álvarez-Errico D, Ramirez RN, Company C, et al. Prostaglandin E2 Leads to the Acquisition of DNMT3A-Dependent Tolerogenic Functions in Human Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cell Rep 2017;21:154–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Loberg MA, Bell RK, Goodwin LO, Eudy E, Miles LA, SanMiguel JM, et al. Sequentially inducible mouse models reveal that Npm1 mutation causes malignant transformation of Dnmt3a-mutant clonal hematopoiesis. Leukemia 2019;33:1635–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ley TJ, Miller C, Ding L, Raphael BJ, Mungall AJ, Robertson A, et al. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2059–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lewis NE, Petrova-Drus K, Huet S, Epstein-Peterson ZD, Gao Q, Sigler AE, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma with divergent evolution to myeloid neoplasms. Blood Adv 2020;4:2261–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gale RE, Lamb K, Allen C, El-Sharkawi D, Stowe C, Jenkinson S, et al. Simpson’s Paradox and the Impact of Different DNMT3A Mutations on Outcome in Younger Adults With Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2072–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cappelli LV, Meggendorfer M, Dicker F, Jeromin S, Hutter S, Kern W, et al. DNMT3A mutations are over-represented in young adults with NPM1 mutated AML and prompt a distinct co-mutational pattern. Leukemia 2019;33:2741–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gaidzik VI, Schlenk RF, Paschka P, Stolzle A, Spath D, Kuendgen A, et al. Clinical impact of DNMT3A mutations in younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results of the AML Study Group (AMLSG). Blood 2013;121:4769–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ahn JS, Kim HJ, Kim YK, Lee SS, Jung SH, Yang DH, et al. DNMT3A R882 Mutation with FLT3-ITD Positivity Is an Extremely Poor Prognostic Factor in Patients with Normal-Karyotype Acute Myeloid Leukemia after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22:61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Balasubramanian SK, Aly M, Nagata Y, Bat T, Przychodzen BP, Hirsch CM, et al. Distinct clinical and biological implications of various DNMT3A mutations in myeloid neoplasms. Leukemia 2018;32:550–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xu Q, Li Y, Lv N, Jing Y, Xu Y, Li W, et al. Correlation Between Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Gene Aberrations and Prognosis of Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:4511–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang L, Shen K, Zhang M, Zhang W, Cai H, Lin L, et al. Clinical Features and MicroRNA Expression Patterns Between AML Patients With DNMT3A R882 and Frameshift Mutations. Front Oncol 2019;9:1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bond J, Touzart A, Leprêtre S, Graux C, Bargetzi M, Lhermitte L, et al. mutation is associated with increased age and adverse outcome in adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 2019;104:1617–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Celik H, Mallaney C, Kothari A, Ostrander EL, Eultgen E, Martens A, et al. Enforced differentiation of Dnmt3a-null bone marrow leads to failure with c-Kit mutations driving leukemic transformation. Blood 2015;125:619–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nangalia J, Nice FL, Wedge DC, Godfrey AL, Grinfeld J, Thakker C, et al. DNMT3A mutations occur early or late in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms and mutation order influences phenotype. Haematologica 2015;100:e438–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Busque L, Mio R, Mattioli J, Brais E, Blais N, Lalonde Y, et al. Nonrandom X-inactivation patterns in normal females: lyonization ratios vary with age. Blood 1996;88:59–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Watson CJ, Papula AL, Poon GYP, Wong WH, Young AL, Druley TE, et al. The evolutionary dynamics and fitness landscape of clonal hematopoiesis. Science 2020;367:1449–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.De Haan G, Lazare SS. Aging of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 2018;131:479–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Steensma DP, Ebert BL. Clonal hematopoiesis as a model for premalignant changes during aging. Exp Hematol 2020;83:48–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Abelson S, Collord G, Ng SWK, Weissbrod O, Mendelson Cohen N, Niemeyer E, et al. Prediction of acute myeloid leukaemia risk in healthy individuals. Nature 2018;559:400–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Desai P, Mencia-Trinchant N, Savenkov O, Simon MS, Cheang G, Lee S, et al. Somatic mutations precede acute myeloid leukemia years before diagnosis. Nature medicine 2018;24:1015–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tovy A, Reyes JM, Gundry MC, Brunetti L, Lee-Six H, Petljak M, et al. Tissue-Biased Expansion of DNMT3A-Mutant Clones in a Mosaic Individual Is Associated with Conserved Epigenetic Erosion. Cell Stem Cell 2020;27:326–35.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, Gibson CJ, Bick AG, Shvartz E, et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2017;377:111–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rauch PJ, Silver AJ, Gopakumar J, McConkey M, Sinha E, Fefer M, et al. Loss-of-Function Mutations in Dnmt3a and Tet2 Lead to Accelerated Atherosclerosis and Convergent Macrophage Phenotypes in Mice. Blood 2018;132:745- [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, Walsh K. CRISPR-mediated gene editing to assess the roles of TET2 and DNMT3A in clonal hematopoiesis and cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research 2018;123:335–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cook EK, Izukawa T, Young S, Rosen G, Jamali M, Zhang L, et al. Comorbid and inflammatory characteristics of genetic subtypes of clonal hematopoiesis. Blood Adv 2019;3:2482–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yoshizato T, Dumitriu B, Hosokawa K, Makishima H, Yoshida K, Townsley D, et al. Somatic Mutations and Clonal Hematopoiesis in Aplastic Anemia. N Engl J Med 2015;373:35–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Coombs CC, Zehir A, Devlin SM, Kishtagari A, Syed A, Jonsson P, et al. Therapy-Related Clonal Hematopoiesis in Patients with Non-hematologic Cancers Is Common and Associated with Adverse Clinical Outcomes. Cell Stem Cell 2017;21:374–82.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang CRC, Nix D, Gregory M, Ciorba MA, Ostrander EL, Newberry RD, et al. Inflammatory cytokines promote clonal hematopoiesis with specific mutations in ulcerative colitis patients. Experimental Hematology 2019;80:36–41.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Young K, Eudy E, Bell R, Loberg M, Stearns T, Velten L, et al. Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Aging is Initiated at Middle Age Through Decline in Local Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 (IGF1). bioRxiv 2020:2020.07.11.198846 [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hormaechea Agulla D, Matatall KA, Le D, Kain BN, Jaksik R, Kimmel M, et al. Infection Is a Driver of Dnmt3a-Mutant Clonal Hematopoiesis. Blood 2019;134:817- [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sehgal AR, Gimotty PA, Zhao J, Hsu JM, Daber R, Morrissette JD, et al. DNMT3A Mutational Status Affects the Results of Dose-Escalated Induction Therapy in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:1614–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Patel JP, Gonen M, Figueroa ME, Fernandez H, Sun Z, Racevskis J, et al. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1079–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kadia TM, Cortes J, Ravandi F, Jabbour E, Konopleva M, Benton CB, et al. Cladribine and low-dose cytarabine alternating with decitabine as front-line therapy for elderly patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: a phase 2 single-arm trial. Lancet Haematol 2018;5:e411–e21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Venugopal K, Shabashvili DE, Li J, Posada LM, Bennett RL, Feng Y, et al. DNMT3A with Leukemia-Associated Mutations Directs Sensitivity to DNA Damage at Replication Forks. Blood 2019;134:535- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Metzeler KH, Walker A, Geyer S, Garzon R, Klisovic RB, Bloomfield CD, et al. DNMT3A mutations and response to the hypomethylating agent decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2012;26:1106–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Traina F, Visconte V, Elson P, Tabarroki A, Jankowska AM, Hasrouni E, et al. Impact of molecular mutations on treatment response to DNMT inhibitors in myelodysplasia and related neoplasms. Leukemia 2014;28:78–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Coombs CC, Sallman DA, Devlin SM, Dixit S, Mohanty A, Knapp K, et al. Mutational correlates of response to hypomethylating agent therapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2016;101:e457–e60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Casellas Roman HL, Venugopal K, Feng Y, Shabashvili DE, Posada LM, Li J, et al. DNMT3A alterations associated with myeloid malignancies dictate differential responses to hypomethylating agents. Leuk Res 2020;94:106372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Garcia-Manero G, Abaza Y, Takahashi K, Medeiros BC, Arellano M, Khaled SK, et al. Pracinostat plus azacitidine in older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia: results of a phase 2 study. Blood Adv 2019;3:508–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tyner JW, Tognon CE, Bottomly D, Wilmot B, Kurtz SE, Savage SL, et al. Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2018;562:526–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nybakken GE, Canaani J, Roy D, Morrissette JD, Watt CD, Shah NP, et al. Quizartinib elicits differential responses that correlate with karyotype and genotype of the leukemic clone. Leukemia 2016;30:1422–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kurtz SE, Eide CA, Kaempf A, Mori M, Tognon CE, Borate U, et al. Dual inhibition of JAK1/2 kinases and BCL2: a promising therapeutic strategy for acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2018;32:2025–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rau RE, Rodriguez BA, Luo M, Jeong M, Rosen A, Rogers JH, et al. DOT1L as a therapeutic target for the treatment of DNMT3A-mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2016;128:971–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kühn MW, Song E, Feng Z, Sinha A, Chen CW, Deshpande AJ, et al. Targeting Chromatin Regulators Inhibits Leukemogenic Gene Expression in NPM1 Mutant Leukemia. Cancer Discov 2016;6:1166–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Uckelmann HJ, Kim SM, Wong EM, Hatton C, Giovinazzo H, Gadrey JY, et al. Therapeutic targeting of preleukemia cells in a mouse model of. Science 2020;367:586–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lu R, Wang J, Ren Z, Yin J, Wang Y, Cai L, et al. A Model System for Studying the DNMT3A Hotspot Mutation (DNMT3A. Cancer Res 2019;79:3583–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.DiNardo CD, Perl AE. Advances in patient care through increasingly individualized therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16:73–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kishtagari A, Levine RL, Viny AD. Driver mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol 2020;27:49–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sasaki K, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Montalban-Bravo G, Assi R, Jabbour E, Ravandi F, et al. Impact of the variant allele frequency of ASXL1, DNMT3A, JAK2, TET2, TP53, and NPM1 on the outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2020;126:765–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Thol F, Klesse S, Kohler L, Gabdoulline R, Kloos A, Liebich A, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia derived from lympho-myeloid clonal hematopoiesis. Leukemia 2017;31:1286–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Garg M, Nagata Y, Kanojia D, Mayakonda A, Yoshida K, Haridas Keloth S, et al. Profiling of somatic mutations in acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3-ITD at diagnosis and relapse. Blood 2015;126:2491–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Couronné L, Bastard C, Bernard OA. TET2 and DNMT3A mutations in human T-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2012;366:95–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Choi J, Goh G, Walradt T, Hong BS, Bunick CG, Chen K, et al. Genomic landscape of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Nat Genet 2015;47:1011–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Neumann M, Heesch S, Schlee C, Schwartz S, Gökbuget N, Hoelzer D, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in adult ETP-ALL reveals a high rate of DNMT3A mutations. Blood 2013;121:4749–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Nguyen L, Zhang X, Roberts E, Yun S, McGraw K, Abraham I, et al. Comparison of mutational profiles and clinical outcomes in patients with acute myeloid leukemia with mutated. Leuk Lymphoma 2020;61:1395–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wang K, Zhou F, Cai X, Chao H, Zhang R, Chen S. Mutational landscape of patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes in the context of RUNX1 mutation. Hematology 2020;25:211–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Stengel A, Kern W, Meggendorfer M, Nadarajah N, Perglerovà K, Haferlach T, et al. Number of RUNX1 mutations, wild-type allele loss and additional mutations impact on prognosis in adult RUNX1-mutated AML. Leukemia 2018;32:295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.You E, Cho YU, Jang S, Seo EJ, Lee JH, Lee KH, et al. Frequency and Clinicopathologic Features of RUNX1 Mutations in Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia Not Otherwise Specified. Am J Clin Pathol 2017;148:64–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Sun QY, Ding LW, Tan KT, Chien W, Mayakonda A, Lin DC, et al. Ordering of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia with partial tandem duplication of MLL (MLL-PTD). Leukemia 2017;31:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kao HW, Liang DC, Kuo MC, Wu JH, Dunn P, Wang PN, et al. High frequency of additional gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia with MLL partial tandem duplication: DNMT3A mutation is associated with poor prognosis. Oncotarget 2015;6:33217–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wang T, Glover B, Hadwiger G, Miller CA, di Martino O, Welch JS. Smc3 is required for mouse embryonic and adult hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol 2019;70:70–84.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Patel JL, Schumacher JA, Frizzell K, Sorrells S, Shen W, Clayton A, et al. Coexisting and cooperating mutations in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res 2017;56:7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Hartmann L, Haferlach C, Meggendorfer M, Kern W, Haferlach T, Stengel A. Myeloid malignancies with isolated 7q deletion can be further characterized by their accompanying molecular mutations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2019;58:698–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Kerr CM, Adema V, Walter W, Hutter S, Snider CA, Nagata Y, et al. Genetics of Monosomy 7 and Del(7q) in MDS Informs Potential Therapeutic Targets. Blood 2019;134:1703- [Google Scholar]

- 149.Stengel A, Kern W, Haferlach T, Meggendorfer M, Haferlach C. The 5q deletion size in myeloid malignancies is correlated to additional chromosomal aberrations and to TP53 mutations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2016;55:777–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Herold T, Metzeler KH, Vosberg S, Hartmann L, Jurinovic V, Opatz S, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with del(9q) is characterized by frequent mutations of NPM1, DNMT3A, WT1 and low expression of TLE4. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2017;56:75–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Scourzic L, Couronné L, Pedersen MT, Della Valle V, Diop M, Mylonas E, et al. DNMT3A(R882H) mutant and Tet2 inactivation cooperate in the deregulation of DNA methylation control to induce lymphoid malignancies in mice. Leukemia 2016;30:1388–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]