Abstract

Objective

Empathic communication in clinical consultations is mutually constructed, with patients first presenting empathic opportunities (statements communicating emotions, challenges, or progress) to which clinicians can respond. We hypothesized that lung cancer patients who did not present empathic opportunities during routine consultations would report higher stigma, anxiety, and depressive symptoms than patients who presented at least one.

Methods

Audio-recorded consultations between lung cancer patients (N = 56) and clinicians were analyzed to identify empathic opportunities. Participants completed questionnaires measuring sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics.

Results

Twenty-one consultations (38 %) did not contain empathic opportunities. Unexpectedly, there was a significant interaction between presenting empathic opportunities and patients’ race on disclosure-related stigma (i.e., discomfort discussing one’s cancer; F = 4.49, p = .041) and anxiety (F = 8.03, p = .007). Among racial minority patients (self-identifying as Black/African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other race), those who did not present empathic opportunities reported higher stigma than those who presented at least one (t = −5.47, p = .038), but this difference was not observed among white patients (t = 0.38, p = .789). Additional statistically significant findings emerged for anxiety.

Conclusion

Disclosure-related stigma and anxiety may explain why some patients present empathic opportunities whereas others do not.

Practice Implications

Clinicians should intentionally elicit empathic opportunities and encourage open communication with patients (particularly from diverse racial backgrounds).

Keywords: lung cancer, stigma, anxiety, empathic opportunities, communication

1. Introduction

Communicating empathically with patients is associated positively with patient-reported health [1] and healthcare engagement outcomes [2]. Empathic communication is particularly important in the context of clinical encounters with lung cancer patients, given the pervasive distress [3,4], perceived stigma [5–7], and barriers to engagement [8,9] that these patients commonly experience. Empathic communication by clinicians may help mitigate stigma and distress and promote engagement, which is associated with better clinical care and health outcomes for patients [10,11].

Communication within a clinical consultation is a bidirectional process in which both the patient and clinician are responding to cues within the conversation [12,13]. Theory and research in empathic communication has focused on characterizing the nature and frequency of patient-initiated empathic opportunities and subsequent clinician responses to those opportunities [14–16]. Empathic opportunities are characterized as patient-initiated statements that clearly and directly communicate emotions (i.e., statements of feeling a positive or negative affective state), challenges (i.e., statements that convey a negative effect of a physical or psychosocial problem on quality of life), or progress (i.e., statements that convey positive development in one’s physical condition, efforts to improve one’s health, or positive life events) [16,17]. For example, when lung cancer patients express negative emotions (e.g., regret, frustration in not being able to quit) about their smoking history, there is a window of opportunity for clinicians to respond empathically, which can manifest in several ways including the physician providing validation, normalizing the patienťs experience, or pursuing the topic further with the patient. These responses to empathic opportunities may help reduce or mitigate some of these negative psychosocial outcomes common among lung cancer patients, such as stigma. Indeed, researchers have begun to develop communication skills training programs to aid clinicians in improving their ability to recognize and respond to these missed opportunities more empathically [18–21].

Several studies have focused on when empathic opportunities are missed by clinicians (i.e., no empathic response was provided in response to a patient) [22,23]. Research has demonstrated an alarmingly high rate (90%) of missed empathic opportunities specifically within clinical consultations for lung cancer [24], which is higher than rates (ranging from 55 to 79%) observed in other patient samples [22,23,25]. These findings emphasize the urgent need for better understanding empathic opportunities within routine clinical consultations for lung cancer, particularly given that depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stigma are commonly reported by lung cancer patients [3,5,9,26] and are associated with poorer patient-clinician communication outcomes in clinical care for lung cancer [27,28].

Several studies across clinical care settings and patient populations have demonstrated that a substantial proportion (45 to 60%) of patients do not present any emotion, challenge, or progress statements during clinical consultations that could be construed as an empathic opportunity [16,25,29]. Given that these patient-initiated statements provide windows of opportunity for clinicians to provide support and empathy to patients, research is needed to understand what factors may contribute to the lack of empathic opportunities within routine consultations. Some patients might not present empathic opportunities because of the effect that the clinician has on the patient within the consultation and vice versa. Additionally, there may be sociodemographic and patient-reported psychosocial characteristics (e.g., depressive symptoms, anxiety, stigma) that explain why some patients present empathic opportunities whereas others do not.

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, findings suggest that compared to non-Hispanic white cancer patients, patients who identify as Black/African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and/or Hispanic report poorer communication from and lower trust in their clinicians [30,31]. However, researchers have reported null findings on whether the presence of empathic opportunities was associated with patients' sociodemographic (e.g., patients' race, sex) and/or visit-related characteristics (e.g., length of time since first visit with clinician) [16,25]. As such, it is currently unknown what sociodemographic variables may differentiate patients who present empathic opportunities during clinical consultations versus those who do not.

To date, the role of psychosocial characteristics in understanding the presentation of empathic opportunities is largely unknown. Stigma, depressive symptoms, and anxiety are psychosocial characteristics that may be relevant to understanding whether lung cancer patients present empathic opportunities to their cancer care providers. Specifically, lung cancer patients who experience high levels of stigma may be less likely to openly communicate with their clinicians due to a fear of being criticized, apprehension about being treated unfairly, or a general discomfort in sharing information about their lung cancer with others [6,32]. Relatedly, those high in anxiety may feel overwhelmed [33] and those high in depressive symptoms may feel hopeless and socially withdrawn [34], which also may be associated with a lower likelihood of presenting empathic opportunities.

The aim of the current study was to examine audio-recorded routine clinical consultations for lung cancer and determine if patients' self-reported experience of lung cancer stigma, depressive symptoms, and/or anxiety differentiated lung cancer patients who did versus did not present empathic opportunities. We hypothesized that patients who did not present any emotion, challenge, or progress statements (i.e., an absence of empathic opportunities) would report significantly higher lung cancer stigma, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, as compared to those who presented with at least one empathic opportunity.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants (N = 56) were men and women who received a consultation for lung cancer. Patients were eligible if they were: 1) diagnosed with lung cancer (within six months) or a new patient (within three months) at the institution; 2) being seen for a consultation for lung cancer or a mass suspicious of lung cancer; 3) formerly or currently smoking cigarettes (i.e., smoked >100 packs in their lifetime); 4) fluent in English; 5) able to provide informed consent; and 6) able to complete study procedures. All participants provided written informed consent, and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Additional information on the sample and methods have been reported in earlier publications [35,36].

2.2. Procedure

A member of the research team approached potentially eligible participants at regularly scheduled medical appointments at cancer care clinics1. Eligible participants who provided informed consent had their clinical consultations audio recorded. Participants also completed validated questionnaires on sociodemographic information, medical characteristics, lung cancer stigma, depressive symptoms, and anxiety within three days of their consultation via a web-based survey portal, over the phone with a member of the research team, or onsite via a hard copy survey.

The audio recordings were later coded by the study team using a slightly modified version of the Empathic Communication Coding System [16,35] to identify the presence of empathic opportunities. Within this coding system, the unit of analysis is a single empathic opportunity (identified as an emotion, challenge, or progress statement using an existing codebook) initiated by the patient. Multiple empathic opportunities can exist within a single consultation. Patients were categorized in the current study based on whether they presented with at least one empathic opportunity versus no empathic opportunities within the consultation. After establishing adequate inter-rater agreement (86%) on coding empathic opportunities from a subsample (10%) of the data, pairs of trained coders independently coded the consultations and met to resolve discrepancies with the assistance of the senior author (MJS) and the original developer of the ECCS. Additional details on the coding system and procedure used in this study have been reported previously [35].

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Lung cancer stigma

The 31-item Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale was used to assess lung cancer stigma, which has demonstrated good reliability and validity [37]. Participants rated items on a 4-point Likert scale ("strongly disagree" to "strongly agree") with higher scores indicating higher stigma. Internal consistency reliability for the total score was excellent (α=.93). Recent advances in theory [9] and research [6] have demonstrated that disclosure-related stigma—defined as the avoidance or discomfort in sharing information about one’s lung cancer—is an important facet of stigma experienced by patients and is associated with adverse psychological and physical health outcomes [7,38]. Given that the current study is focused on evaluating patient-initiated statements that communicate emotions, challenges, or progresses to one’s clinician, we made an a priori decision to evaluate items from the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale in consideration of computing disclosure-related stigma subscale. The study team unanimously agreed upon including 8 items that captured disclosure-related worry (e.g., “I worry that people may judge me when they learn I have lung cancer”) or disclosure-related consequences (e.g., “I was hurt how people reacted to learning I have lung cancer”); the internal consistency reliability for this newly computed subscale (hereby referred to as disclosure-related stigma) was adequate (α=.77).

2.3.2. Depressive symptoms and anxiety

To assess psychological depressive symptoms and anxiety, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale was used [39], which has demonstrated good reliability and validity in other oncology samples [40]. Participants rated 14 items on a 4-point Likert scale ("not at all" to "nearly all the time") to indicate anxiety and depressive symptoms. The 7-item anxiety and depression subscales were computed and used for analyses. Internal consistency reliability estimates for the anxiety (α=.86) and depression (α=.69) subscales were adequate.

2.4. Analytic Strategy

Pearson's product-moment correlations and descriptive statistics were computed to evaluate sample characteristics. Analysis of Covariance was conducted to evaluate whether participants who presented with at least one empathic opportunity differed significantly from those who did not present any empathic opportunities on the outcomes of total lung cancer stigma, disclosure-related stigma, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, which were entered as dependent variables in separate analyses. This analytic approach was selected to be consistent with approaches used by researchers that compared participants who did vs. did not present empathic opportunities by sociodemographic or medical visit-related characteristics [16,25]. Patients' age, sex, and race were selected as a priori covariates, and any other sociodemographic or medical characteristic associated with any outcome at p < .05 was also included as a covariate. Two-tailed significance tests were used and p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Sample characteristics

As previously reported [35], 99 patients were approached to participate, including three who were ineligible, 26 who declined participation, and 14 who did not complete the study procedures. Among the 56 participants with analyzable data, 35 participants (62.5%) presented with at least one empathic opportunity and 21 participants (37.5%) did not present empathic opportunities during their clinical consultations.

Participants had a mean age of 67.95 years (SD = 9.06). Most participants were married or living as married (n = 34, 60.7%), identified as white (n = 43, 76.8%), had attained a bachelor's degree level of education or higher (n = 34, 60.7%), and formerly smoked (n = 47, 83.9%). Twenty-seven participants had early stage lung cancer (48.2%), 21 had later stage disease (37.5%), and stage of disease was unknown for eight participants (14.3%). Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Zero-order correlations between total lung cancer stigma, disclosure-related stigma, anxiety, and depressive symptoms were all statistically significant (r = .35 to .83, all p < .009).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and demographics (N = 56).

| n | Mean | Standard Deviation | Possible Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 56 | 67.95 | 9.06 | - |

| HADS Anxiety | 56 | 6.00 | 4.41 | 0–21 |

| HADS Depressive Symptoms | 56 | 4.14 | 3.02 | 0–21 |

| CLCSS Total Lung Cancer Stigma | 52 | 51.88 | 12.45 | 31–124 |

| CLCSS Dlsclosure-related Stigma | 54 | 13.02 | 3.67 | 8–32 |

| n | % | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 23 | 58.9 | ||

| Female | 33 | 41.1 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 43 | 76.8 | ||

| Black/African American | 7 | 12.5 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 | 5.4 | ||

| Other race | 1 | 1.8 | ||

| Did not report | 2 | 3.6 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/Living as married | 34 | 60.7 | ||

| Not married | 20 | 35.7 | ||

| Did not report | 2 | 3.6 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Partial high school | 3 | 5.4 | ||

| High school graduate | 8 | 14.3 | ||

| Partial college | 11 | 19.6 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 13 | 23.2 | ||

| Graduate degree | 21 | 37.5 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Currently smoked | 9 | 16.1 | ||

| Formerly smoked | 47 | 83.9 | ||

| Stage of disease | ||||

| Early stage | 27 | 48.2 | ||

| Late stage | 21 | 37.5 | ||

| Missing | 8 | 14.3 |

Note. HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. CLCSS = Cataldo lung Cancer Stigma Scale. Early stage signifies Stages I-IIIa non-small cell lung cancer and limited stage small-cell lung cancer. Late stage signifies Stages IIIb-IV non-small-cell lung cancer and extensive stage small-cell lung cancer.

3.1.2. Covariates

Participants differed significantly on total lung cancer stigma by smoking history (t = 2.57, p = .013) and education (t = 2.03, p = .048); those who currently smoked (M = 61.09, SD = 11.13) reported higher stigma than those who formerly smoked (M = 49.95, SD = 11.94), and those with less than a bachelor's degree level of education (M = 55.85, SD = 14.19) reported higher stigma than those who attained a bachelor's degree or higher (M = 48.97, SD = 10.29). Participants who currently smoked also reported higher disclosure-related stigma (M = 15.41, SD = 2.74) than those who formerly smoked (M = 12.54, SD = 13.67), t = 2.22, p = .031. Additionally, participants differed significantly on anxiety with regard to sex (t = −3.02, p = .004) and stage of disease (t = 3.32, p = .002); women (M = 7.44, SD = 4.41) reported higher anxiety than men (M = 4.09, SD = 3.67) and those with earlier stage disease (M = 8.05, SD = 4.67) reported higher anxiety than those with late stage disease (M = 4.05, SD = 3.35). Based on these findings, education, smoking history, and disease stage were entered along with the a priori covariates (i.e., age, sex, race) in subsequent analyses.

3.1.3. Presentation of empathic opportunities

Our primary research question focused on whether patients who presented with at least one empathic opportunity differed from those who did not present empathic opportunities by total lung cancer stigma, disclosure-related stigma, anxiety, and depressive symptoms2. When testing the statistical assumptions for including covariates in the model (i.e., the covariate should be included only if it does not interact significantly with an independent variable to predict the outcome), we found that race3 (but no other covariate) interacted significantly with the presentation of empathic opportunities in predicting disclosure-related stigma (F = 4.49, p = .041) and anxiety (F = 8.03, p = .007). As such, we deviated from our a priori analytic plan and probed these interactions following established guidelines to compare adjusted mean outcomes by participants' race and presentation of empathic opportunities [41].

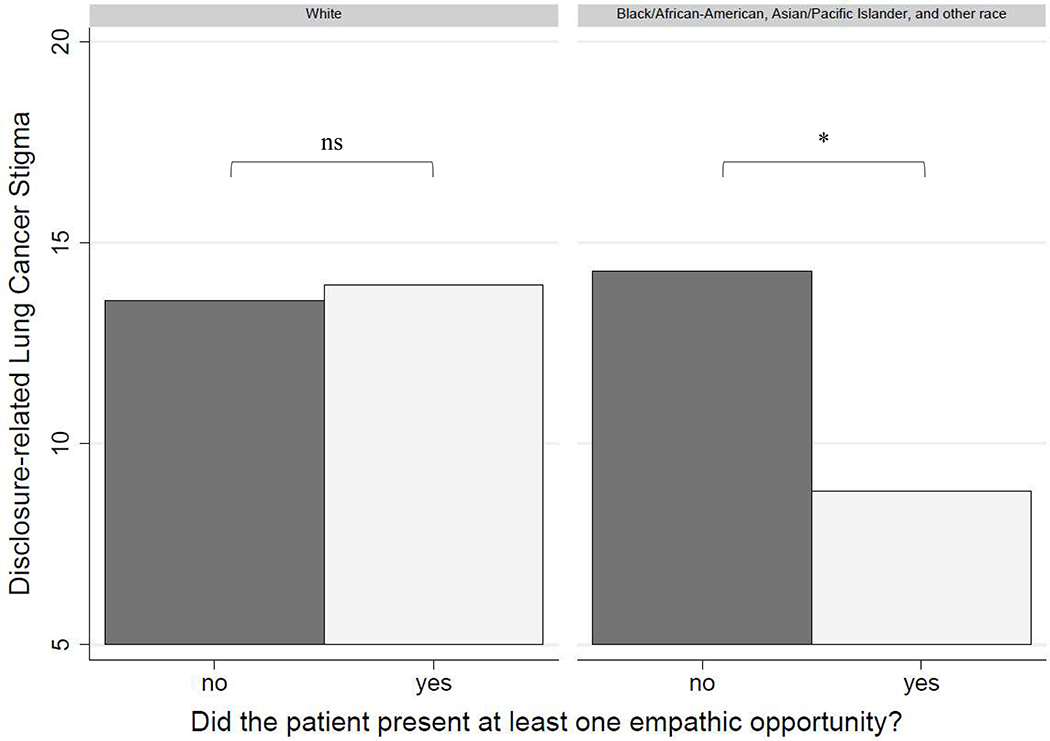

As shown in Figure 1, we found that among racial minority participants, those who did not present empathic opportunities reported significantly higher disclosure-related stigma (Madj = 14.30, SE = 1.64, 95% CI [10.97, 17.62]) than those who presented at least one (Madj = 8.82, SE = 1.85, 95% CI [5.09, 12.57]), t = −5.47, p = .038, 95% CI [−10.63, −0.31]. However, among white participants, there was no significant difference in disclosure-related stigma between those who presented at least one empathic opportunity (Madj = 13.95, SE = 0.78, 95% CI [12.37, 15.54]) compared to those who did not present any empathic opportunities (Madj = 13.57, SE = 1.08, 95% CI [11.38, 15.76]), t = 0.38, p = .789, 95% CI [−2.48, 3.24].

Figure 1.

Results for probing the significant interaction between race and presentation of an empathic opportunity on disclosure-related lung cancer stigma. Results are adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking history, and disease stage.

* = p < .05; ns = p > .05.

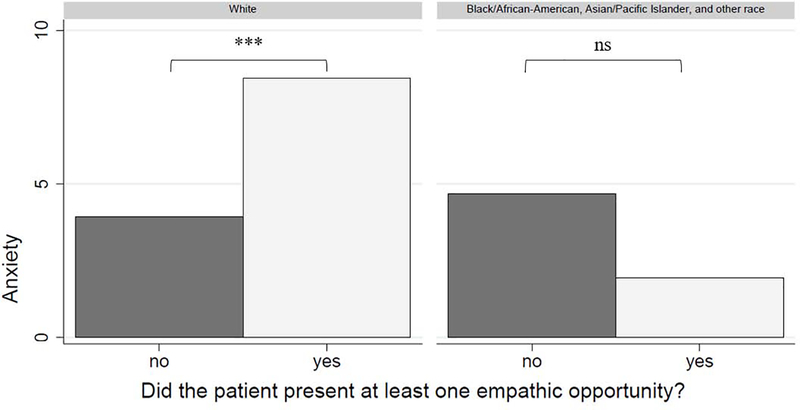

As shown in Figure 2, we found that among white participants, those who presented at least one empathic opportunity reported significantly higher anxiety (Madj = 8.45, SE = 0.71, 95% CI [7.01, 9.88]) than those who did not present any empathic opportunities (Madj = 3.94, SE = 1.00, 95% CI [1.92, 5.96]), t = 4.51, p = .001, 95% CI [1.90,7.12]. However, among racial minority participants, there was no significant difference in anxiety between those who presented at least one empathic opportunity (Madj = 1.94, SE = 1.72, 95% CI [−1.54, 5.42]) and those who did not present any empathic opportunities (Madj = 4.68, SD = 1.52, 95% CI [1.59, 7.77]), t = −2.74, p = .254, 95% CI [−7.53, 2.05].

Figure 2.

Results for probing the significant interaction between race and presentation of an empathic opportunity on anxiety. Results are adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking history, and disease stage.

*** = p < .001; ns = p > .05.

Patients who presented with at least one empathic opportunity did not differ significantly from those who did not present empathic opportunities regarding depressive symptoms (F = 1.14, p = .293) or total lung cancer stigma (F = 1.09, p = .303).

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This study identified sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics that may explain why some patients with lung cancer present empathic opportunities during routine clinical consultations, whereas others do not. Our findings suggest that among racial minority lung cancer patients, disclosure-related stigma may be a prominent barrier for patients to initiate empathic opportunities with their cancer care providers. Importantly, racial minority participants did not report higher levels of disclosure-related stigma compared to white participants. Rather, our findings suggest that among racial minority participants, those who did not present empathic opportunities reported significantly higher levels of disclosure-related stigma than patients who presented at least one. These findings are concerning in that similar levels of stigma may be associated with more negative consequences (e.g., withholding statements expressing emotions, challenges, or progress) for lung cancer patients who identify as Black/African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other race. These results should cautiously be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather than confirming, however, given that a priori analyses to test the original research question could not be conducted as planned because of the significant interaction observed between race and the presentation of empathic opportunities on stigma and anxiety. These emerging findings, however, suggest that additional research is needed to more fully understand the interplay between patient-clinician communication among racial minority groups, stigma, anxiety, and the presence of empathic opportunities within routine clinical consultations for lung cancer.

Racial minorities—and patients who identify as Black/African American in particular—often experience mistrust in and discrimination from the healthcare system [42,43], as well as poorer communication [44]. Prior negative experiences with healthcare systems could result in racial minority groups feeling constrained in communicating with clinicians in a routine consultation, especially for those who report experiencing lung cancer stigma. Additionally, many Asian cultures involve social norms of suppressing emotions to maintain group harmony [45]; research has demonstrated that Chinese American cancer patients frequently report ambivalence about expressing one's emotions, which is associated with higher depressive symptoms and poorer quality of life and may also contribute to disclosure-related stigma [46,47]. Additionally, higher psychological distress was associated with a reluctance to express negative emotions due to a fear of its negative impact on others in a sample of Japanese patients with lung cancer [48]. A rich avenue for future research is to examine how lung cancer stigma interacts with other perceptions of stigma and discrimination (e.g., about one's race) and sociocultural norms (e.g., ambivalence about emotional expression) to predict health-related and communication outcomes for lung cancer patients. Although extensive research has demonstrated the negative health consequences of stigma [49,50], much of this work has been focused on examining a single form of stigma rather than intersectional stigma (i.e., the coexistence of multiple stigmatized identities; also referred to as multilayered, double, or stacked stigma) [51–53]. Findings from the current study demonstrate that similar levels of lung cancer stigma can result in different patterns of communication outcomes based on patients' sociodemographic characteristics. As such, future research should build on these findings and test whether the health-related and clinical care consequences of lung cancer stigma vary by other sociodemographic (e.g., sex, age) and psychosocial characteristics (e.g., smoking-related stigma, experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination). Additionally, psychosocial interventions that aim to reduce lung cancer stigma may be maximally efficacious if they specifically target the multiple layers of stigma that patients experience [54].

We also found that among white participants, those who presented at least one empathic opportunity evidenced higher anxiety compared to patients who did not present any. However, there was no difference in anxiety when comparing the racial minority participants who did vs. did not present an empathic opportunity. These findings suggest that anxiety may play an important role in predicting the presentation of empathic opportunities for this subgroup of patients, whereas lung cancer stigma may play a more prominent role in the presentation of empathic opportunities among racial minority lung cancer patients. One interpretation of these findings is that racial minority patients experience stigma as a barrier to disclosing their empathic opportunities, whereas white patients experience anxiety as a facilitator to disclosing empathic opportunities. These findings are concerning in that both stigma and anxiety can be conceptualized as forms of psychological distress [5,55,56], yet they may yield divergent effects on communication outcomes by lung cancer patients' self-identified race. There is an established need for clinicians to engage in higher quality communication (e.g., increase partnership building, improve patient-centered nature of communication) with racial minority patients [44], and the current findings underscore the urgency of this need to reduce disparities in communication outcomes by patients' race.

The small sample size in the current study limits statistical power and robust conclusions. Relatedly, too few participants reported their race as Black/African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and/or other race to analyze as separate groups, and future research should purposively sample participants from each of these groups to facilitate a more robust analysis. Additionally, we were not able to analyze types of empathic opportunities (emotion, challenge, progress) separately, given that 34.3% of participants who presented at least one empathic opportunity presented multiple types within their clinical consultation. Caution is warranted in generalizing these results more broadly to other patient populations and cancer care clinicians. An additional limitation is that clinician-level factors such as clinicians’ race and ethnicity were not assessed and thus remain unexplored in the current study. Given that empathic communication is mutually constructed between patients and clinicians, future studies should assess the role of clinician-level factors and interactive effects between patient- and clinician factors (e.g., racial concordance) in predicting patient-initiated empathic opportunities.

Future research could build on the current findings to better understand for whom and under what conditions stigma is a barrier to open patient-clinician communication. Additionally, it is unknown whether an unexplained third variable (e.g., clinicians’ communication style, patients’ ambivalence of emotional expression) may explain the findings. Finally, future researchers should consider using video in addition to audio recordings to capture non-verbal communication cues within clinical consultations, which would provide a more robust perspective of patient-clinician communication.

4.2. Conclusion

Results from this hypothesis-generating study suggest that anxiety and disclosure-related stigma may explain why some lung cancer patients present empathic opportunities during a clinical consultation whereas others do not. These findings add to the growing body of evidence that lung cancer stigma may hinder patient engagement in clinical care [57], supporting theoretical models of lung cancer stigma [9]. Additionally, these findings raise awareness in the patient-clinician communication literature to the importance of the absence of empathic opportunities (i.e., those that are never presented by the patient) in addition to the relatively better studied observations about "missed" (i.e., presented by the patient but not responded to) empathic opportunities by clinicians. Future research should also investigate whether clinician-initiated communication strategies are effective in eliciting empathic opportunities from patients; such an investigation would identify skills for clinicians to use for intentionally eliciting patients' concerns and improving communication.

4.3. Practice Considerations

This study identifies a subgroup of lung cancer patients who may benefit from greater efforts by clinicians to first elicit patients' empathic opportunities through the use of specific communication skills (e.g., encouraging the expression of feelings, such as "How have you been doing emotionally with the diagnosis", "Iťs important to me to understand how you are dealing with all of this emotionally. How are you feeling?", or "Whaťs making you most anxious?") [20]. Doing this may inoculate disclosure-related stigma and encourage patients to communicate more openly. This intentional welcoming of patients' positive and negative experiences could help improve patient-clinician communication and give clinicians more tools to create a supportive environment for patients to present empathic opportunities. Regarding implications for psychosocial interventions, communication intervention approaches (e.g., empathic communication training for clinicians) may be helpful for reducing stigma and improving the quality of patient-clinician communication in the context of lung cancer care [58], particularly for patients from racial minority groups. This study also suggests the need to explicitly assess for stigma to better identify lung cancer patients who may not spontaneously present their psychosocial concerns.

Highlights.

Stigma may hinder empathic opportunities for racial minority lung cancer patients

Anxiety may facilitate empathic opportunities for white lung cancer patients

Greater efforts by clinicians to elicit empathic opportunities may be beneficial

Acknowledgments

The authors thank those who participated in this research.

Funding Sources

This work was supported in part by National Cancer Institute Grants (T32CA009461, P30CA008748, R03CA193986, R01CA207442–03S1, and K07CA207580). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

Each participating physician was either a radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, or a thoracic surgeon at the institution and provided informed consent to take part in this study and have their clinical consultations recorded.

Of note, smoking history groups (currently smoked vs. formerly smoked) did not differ significantly in the presence of patient-initiated empathic opportunities, X2(1) = 0.22, p = .639.

Too few participants reported their race as Black/African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and/or other race to analyze as separate groups and were thus combined into one analytic category.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Lelorain S, Brédart A, Dolbeault S, Sultan S, A systematic review of the associations between empathy measures and patient outcomes in cancer care, Psychooncology. 21 (2012)1255–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV, The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance, Eval. Heal. Prof. 27 (2004) 237–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, Greig D, Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age, J. Affect. Disord. 141 (2012) 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S, The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site, Psychooncology. 10 (2001) 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chambers SK, Dunn J, Occhipinti S, Hughes S, Baade P, Sinclair S, Aitken J, Youl P, O'Connell DL, A systematic review of the impact of stigma and nihilism on lung cancer outcomes, BMC Cancer. 12 (2012) 184–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hamann HA, Shen MJ, Thomas AJ, Lee SJC, Ostroff JS, Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of a Patient-Reported Outcome measure for lung cancer stigma: The Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory (LCSI), Stigma Heal 3 (2018) 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ostroff JS, Riley KE, Shen MJ, Atkinson TM, Williamson TJ, Hamann HA, Lung cancer stigma and depression: Validation of the Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory, Psychooncology. 28 (2019) 1011–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Carter-Harris L, Hermann CP, Schreiber J, Weaver MT, Rawl SM, Lung cancer stigma predicts timing of medical help-seeking behavior, Oncol. Nurs. Forum 41 (2014) E203–E210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hamann HA, Ostroff JS, Marks EG, Gerber DE, Schiller JH, Lee SJC, Stigma among patients with lung cancer: A patient-reported measurement model, Psychooncology. 23 (2014) 81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hibbard JH, Greene J, What the evidence shows about patient activation: Better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs, Health Aff 32 (2013) 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Michaels M, Weiss ES, Guidry JA, Blakeney N, Swords L, Gibbs B, Yeun S, Rytkonen B, Goodman R, Jarama SL, Greene AL, Patel S, The promise of community-based advocacy and education efforts for increasing cancer clinical trials accrual, J. Cancer Educ 27 (2012) 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Maynard DW, Heritage J, Conversation analysis, doctor-patient interaction and medical communication, Med. Educ. 39 (2005) 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Heritage J, Maynard DW, Problems and Prospects in the Study of Physician-Patient Interaction: 30 Years of Research, Annu. Rev. Sociol 32 (2006) 351–374. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Branch WT, Malik TK, Using 'Windows of Opportunities' in Brief Interviews to Understand Patients' Concerns, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 269 (1993) 1667–1668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R, A model of empathic communication in the medical interview, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 277 (1997) 678–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bylund CL, Makoul G, Examining empathy in medical encounters: An observational study using the Empathic Communication Coding System, Health Commun. 18 (2005) 123–140.16083407 [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bylund CL, Makoul G, Empathic communication and gender in the physician-patient encounter, Patient Educ. Couns. 48 (2002) 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Banerjee SC, Haque N, Bylund CL, Shen MJ, Rigney M, Hamann HA, Parker PA, Ostroff JS, Responding empathically to patients: A communication skills training module to reduce lung cancer stigma, Transl. Behav. Med (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bonvicini KA, Perlin MJ, Bylund CL, Carroll G, Rouse RA, Goldstein MG, Impact of communication training on physician expression of empathy in patient encounters, Patient Educ. Couns. 75 (2009) 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pehrson C, Banerjee SC, Manna R, Shen MJ, Hammonds S, Coyle N, Krueger CA, Maloney E, Zaider T, Bylund CL, Responding empathically to patients: Development, implementation, and evaluation of a communication skills training module for oncology nurses, Patient Educ. Couns 99 (2016) 210–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Foster A, Chaudhary N, Kim T, Waller JL, Wong J, Borish M, Cordar A, Lok B, Buckley PF, Using virtual patients to teach empathy: A randomized controlled study to enhance medical students' empathic communication, Simul. Healthc. 11 (2016) 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Easter DW, Beach W, Competent patient care is dependent upon attending to empathic opportunities presented during interview sessions, Curr. Surg. 61 (2004) 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J, A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 284 (2000) 1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Morse DS, Edwardsen EA, Gordon HS, Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication, Arch. Intern. Med. 168 (2008) 1853–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hsu I, Saha S, Korthuis PT, Sharp V, Cohn J, Moore RD, Beach MC, Providing support to patients in emotional encounters: A new perspective on missed empathic opportunities, Patient Educ. Couns. 88 (2012) 436–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Williamson TJ, Kwon DM, Riley KE, Shen MJ, Hamann HA, Ostroff JS, Lung cancer stigma: Does smoking history matter?, Ann. Behav. Med 54 (2020) 535–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shen MJ, Hamann HA, Thomas AJ, Ostroff JS, Association between patient-provider communication and lung cancer stigma, Support. Care Cancer 24 (2016) 2093–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Slatore CG, Golden SE, Ganzini L, Wiener RS, Au DH, Distress and patient-centered communication among veterans with incidental (not screen-detected) pulmonary nodules: A cohort study, Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 12 (2015) 184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mjaaland TA, Finset A, Jensen BF, Gulbrandsen P, Physicians' responses to patients' expressions of negative emotions in hospital consultations: A video-based observational study, Patient Educ. Couns. 85 (2011) 356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Song L, Weaver MA, Chen RC, Bensen JT, Fontham E, Mohler JL, Mishel M, Godley PA, Sleath B, Associations between patient-provider communication and sociocultural factors in prostate cancer patients: A cross-sectional evaluation of racial differences, Patient Educ. Couns 97 (2014) 339–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Palmer NRA, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Arora NK, Rowland JH, Aziz NM, Blanch-Hartigan D, Oakley-Girvan I, Hamilton AS, Weaver KE, Racial and ethnic disparities in patient-provider communication, quality-of-care ratings, and patient activation among long-term cancer survivors, J. Clin. Oncol 32 (2014) 4087–4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A, Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: A qualitative study, BMJ. (2004) 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Duggleby W, Ghosh S, Cooper D, Dwernychuk L, Hope in newly diagnosed cancer patients, J. Pain Symptom Manage 46 (2013) 661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Saracino RM, Rosenfeld B, Nelson CJ, Performance of four diagnostic approaches to depression in adults with cancer, Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 51 (2018) 90–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shen M, Ostroff J, Hamann H, Haque N, Banerjee S, McFarland D, Molena D, Bylund C, Structured analysis of empathic opportunities and physician responses during lung cancer patient-physician consultations, J. Health Commun 24 (2019) 711–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Williamson TJ, Ostroff JS, Haque N, Martin CM, Hamann HA, Banerjee SC, Shen MJ, Dispositional shame and guilt as predictors of depressive symptoms and anxiety among adults with lung cancer: The mediational role of internalized stigma, Stigma Heal (2020) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cataldo JK, Slaughter R, Jahan TM, Hwang WJ, Measuring stigma in people with lung cancer: Psychometric testing of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale, Oncol. Nurs. Forum 1 (2011) 46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Williamson TJ, Choi AK, Kim JC, Garon EB, Shapiro JR, Irwin MR, Goldman JW, Bornyazan K, Carroll JM, Stanton AL, A longitudinal investigation of internalized stigma, constrained disclosure, and quality of life across 12 weeks in lung cancer patients on active oncologic treatment, J. Thorac. Oncol 13 (2018) 1284–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zigmond AS, Snaith RP, The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Acta Psychiatr. Scand 67 (1983) 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D, The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review, J. Psychosom. Res. 52 (2002) 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Williams R, Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects, Stata J 12 (2012) 308–331. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cuevas AG, O'Brien K, Saha S, African American experiences in healthcare: "I always feel like I'm getting skipped over," Heal. Psychol. 35 (2016) 987–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lauderdale DS, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Kandula NR, Immigrant perceptions of discrimination in health care: The California health interview survey 2003, Med. Care 44 (2006) 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, Hernandez MH, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K, Bylund CL, The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: A systematic review of the literature, J. Racial Ethn. Heal. Disparities. 5 (2018) 117–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chen GM, Chung J, The impact of Confucianism on organizational communication, Commun. Q. 42 (1994) 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lu Q, Man J, You J, LeRoy AS, The link between ambivalence over emotional expression and depressive symptoms among Chinese breast cancer survivors, J. Psychosom. Res 79 (2015) 153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lu Q, Tsai W, Chu Q, Xie J, Is expressive suppression harmful for Chinese American breast cancer survivors?, J. Psychosom. Res 109 (2018) 51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Okuyama T, Endo C, Seto T, Kato T, Kato M, Seki N, Akechi T, Furukawa TA, Eguchi K, Hosaka T, Cancer patients' reluctance to disclose their emotional distress to their physicians: A study of Japanese patients with lung cancer, Psychooncology. 17 (2008) 460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Logie C, Gadalla TM, Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV, AIDS Care 21 (2009) 742–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mak WWS, Poon CYM, Pun LYK, Cheung SF, Meta-analysis of stigma and mental health, Soc. Sci. Med. 65 (2007) 245–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Williamson TJ, Mahmood Z, Kuhn TP, Thames AD, Differential relationships between social adversity and depressive symptoms by HIV status and racial/ethnic identity, Heal. Psychol 36 (2017) 133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, Banik S, Turan B, Crockett KB, Pescosolido B, Murray SM, Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health, BMC Med 17 (2019) 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Conlon A, Gilbert D, Jones B, Aldredge P, Stacked stigma: Oncology social workers' perceptions of the lung cancer experience, J. Psychosoc. Oncol 28 (2010) 98–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Henkel KE, Brown K, Kalichman SC, AIDS-related stigma in individuals with other stigmatized identities in the USA: A review of layered stigmas, Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass. 2 (2008) 1586–1599. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Sellick SM, Edwardson AD, Screening new cancer patients for psychological distress using the hospital anxiety and depression scale, Psychooncology. 16 (2007) 534–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Meyer IH, Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence, Psychol. Bull. 129 (2003) 674–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Price S, Ostroff J, Shen M, Thomas A, Lee S, Hamann H, Advocacy and stigma among patients with lung cancer, (2017).

- [58].Hamann HA, VerHoeve ES, Carter-Harris L, Studts JL, Ostroff JS, Multilevel opportunities to address lung cancer sttigma across the cancer control continuum, J. Thorac. Oncol 13 (2018) 1062–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]