Abstract

Macrophages are critical for regulating inflammatory responses. Environmental signals polarize macrophages to either a pro-inflammatory (M1) state or an anti-inflammatory (M2) state. We observed that the microRNA cluster mirn23a, coding for miRs-23a~27a~24–2, regulates mouse macrophage polarization. Gene expression analysis of mirn23a deficient myeloid progenitors revealed a decrease in Toll like receptor and interferon signaling. Mirn23a−/− bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) have an attenuated response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) demonstrating an anti-inflammatory phenotype in mature cells. In vitro, mirn23a−/− BMDMs have decreased M1 responses and an enhanced M2 responses. Overexpression of mirn23a has the opposite effect enhancing M1 and inhibiting M2 gene expression. Interestingly expression of mirn23a miRNAs goes down with inflammatory stimulation and up with anti-inflammatory stimulation suggesting that its regulation prevents locking macrophages into polarized states. M2 polarization of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) correlates with poor outcome for many tumors, so to determine if there was a functional consequence of mirn23a loss modulating immune cell polarization we assayed syngeneic tumor growth in wildtype and mirn23a−/− mice. Consistent with the increased anti-inflammatory/ immunosuppressive phenotype in vitro, mirn23a−/− mice inoculated with syngeneic tumor cells had worse outcomes compared to wildtype mice. Co-injecting tumor cells with mirn23a−/− BMDMs into wildtype mice phenocopied tumor growth in mirn23a−/− mice supporting a critical role for mirn23a miRNAs in macrophage mediated tumor immunity. Our data demonstrates that mirn23a regulates M1/M2 polarization and suggests that manipulation of mirn23a miRNA can be used to direct macrophage polarization to drive a desired immune response.

Keywords: microRNA, mirn23a, macrophage polarization, inflammation, tumor associated macrophage

Introduction

Macrophages are critical effector cells of the innate immune system that respond to danger signals from pathogens and tissue damage(1). Present in every tissue, they are first responders to challenges from the environment. In the absence of host challenge, macrophages will act to promote tissue repair and development, often clearing away dead cells(2). Upon pathogen challenge, macrophages switch their function to cause local, non-specific inflammation in an attempt to clear the challenge and recruit other immune cells to help. Upon clearance of the pathogen, macrophages will return to their previous functional state and repair damage generated by the inflammatory response(3).

Macrophage plasticity is an important factor for both promoting and resolving inflammation(4). Classically activated M1 pro-inflammatory macrophages are generated in response to Toll Like Receptor (TLR) ligands such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and IFNγ while alternatively activated M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages are generated in response to T helper cell 2 (Th2) cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13. The ability to toggle between these two activated states along the M1/M2 spectrum make macrophages a crucial part of immune responses in multiple disease environments. Thus, “re-education” of macrophages in disease contexts could act as a therapeutic strategy for treatment.

Molecular regulation of macrophage polarization is complex. Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, TNF and interferons promote M1 polarization, whereas M-CSF, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 (alone and/ or in combination) promote acquisition of an M2 phenotype(5). Transcription factors are activated downstream of these soluble signals and include M1 promoting factors: NF-κB, AP-1, IRF1, IRF5, and STAT1 and M2 promoting factors: STATs 3,5,6, IRF4, and PPARγ(6, 7). Epigenetic modification such as DNA and histone methylation as well as histone acetylation influence macrophage polarity through regulating the accessibility of transcription factors to chromatin(8, 9). Recently, microRNAs (miRNAs) were shown to be an additional layer of genetic regulation in macrophage polarization(10). MiRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs that target the 3’UTR of their target mRNAs that result in degradation/translational repression of their target transcripts(11). MiRNA-profiling demonstrates that over 100 miRNAs have differential expression in murine bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) between M1 and M2 polarizing conditions(12). MiRNAs upregulated in M1 polarized macrophages compared to M2 macrophages include miR-155–5p, miR-181a and miR-451. MiRNAs downregulated in M1 cells compared to M2 include miR-125–5p, miR-143–3, miR-145–5p and miR-146a-3p. Altering miRNA expression impacts macrophage polarization. Mir155−/− mice are refractory to the development of colitis induced by inflammatory chemical stimuli(13). This protection is mediated by increased M2 polarization of the mir155−/− macrophages. Macrophages treated with microvesicles carrying miR-155 induced an M1 phenotype(14). MiR-146a has the opposite effect on macrophage polarization. Mir146a−/− macrophages are hyperresponsive to LPS stimulation with increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF, IL-6, and IL-1β(15). Conversely, overexpression of miR-146a in peritoneal macrophages enhances M2 polarization and decreases M1 polarization(16). Inflammation requires precise regulation and current data suggest that miRNAs are involved in buffering inflammatory signaling. The ability of miRNAs to buffer the expression of multiple transcription factors and signaling transducers that regulate macrophage polarization make them attractive targets for manipulating immune responses.

Previously, we demonstrated that the miRNA gene cluster mirn23a, coding for 3 mature miRNAs miR-23a~27a~24–2, promotes myeloid development at the expense of B cell development using overexpression and genetic knockout models(17, 18). In these studies, we showed that mirn23a targets genes crucial to cell fate decisions in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs)(19). The mirn23a miRNAs are expressed in HSPCs and continues to be expressed in mature hematopoietic cells with highest expression observed in monocytes and granulocytes(17).

Mirn23a miRNAs are implicated in the regulation of macrophage function, but it is not clear from overexpression and inhibitor studies whether these miRNAs promote or repress inflammatory phenotypes. Importantly, the majority of studies have examined individual miRNAs of the cluster and not studied the effect of simultaneously overexpressing or antagonizing all three cluster miRNAs. MiR-27a is upregulated in both human and mouse macrophages by LPS treatment and 3’ UTR Luciferase assays demonstrate that miR-27a has the ability to directly repress the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10(20). Overexpression of miR-27a mimics decreased production of IL-10 in macrophages whereas miR-27a inhibitors have the opposite effect(20, 21). In addition to inflammatory effects mediated through the targeting of IL-10, miR-27a was also observed to augment TLR mediated production of Type I interferons through the targeting of Siglec1 and Trim27(22). However other reports suggest that miR-27a induces M2 anti-inflammatory polarization of macrophages(23, 24). Two reports suggest that miR-24 promotes M2 anti-inflammatory polarization of macrophages. MiR-24 overexpression was shown to antagonize expression of M1 related molecules TNF, IL-6, IL-12,and iNOS; and conversely promote the expression of M2 related molecules CD206 and Arg-1(25, 26). However contradicting results were obtained with miR-24 mimic expression in RAW264.7 murine macrophages which resulted in decreased expression of M2 genes Arg1, Fizz1 and IL-10(27). The same group showed that miR-24 inhibitors decreased expression of these M2 markers. Fewer studies have addressed the role of miR-23a in macrophage function, however two studies both supported a role for promoting inflammatory polarization of macrophages(28, 29).

So far, all studies examining mirn23a miRNA function in macrophages have only manipulated expression of one miRNA at a time and have used overexpression and knockdown approaches. To address the discrepancies in these models of non-physiological expression, we used mirn23a germline knockout mice to elucidate the function of mirn23a in macrophage polarization. We observe that mirn23a miRNAs regulate macrophage responses associated with polarization. The majority of mirn23a’s affects appear to be pro-inflammatory. RNA-seq data reveal a strong downregulation of inflammatory signaling pathways in mirn23a−/− myeloid progenitors. In mature mirn23a deficient macrophages we observe increases in production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 with decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF and IL1β. Phenotypic analysis of M1 and M2 polarized wildtype and mirn23a knockout-derived macrophages demonstrated an inhibition of M1 polarization and an enhancement of M2 macrophages of knockout cells. Lastly to observe an in vivo functional effect on increased M2 polarization of macrophages, we inoculated wildtype and mirn23a−/− mice with two syngeneic tumor cell lines ovarian cancer ID8 and Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC). We observed in vivo that syngeneic tumors grow better in mirn23a−/− mice. The mirn23a−/− increase in tumor growth can be mimicked in wildtype mice by co-injecting mirn23a−/− macrophages with tumor cells supporting a critical role for mirn23a in macrophage mediate tumor immunity. The data demonstrates a role for mirn23a in macrophage polarization and implies that pharmaceutically targeting mirn23a miRNA in macrophages could be used for programming their polarization/ activity. Modulating macrophage inflammatory activity would be useful for improving tumor immunity, as well as for the treatment of infectious and autoimmune diseases.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Culture

For in vitro macrophage experiment bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were prepared from bone marrow isolated from wildtype and mirn23a−/− C57BL/6 mice. Briefly, bone marrow was flushed from femurs and tibias of individual mice with sterile phosphate buffered saline pH 7.4 (PBS). Red blood cells were lysed using ACK lysis buffer (150mM NH4Cl, 10mM KHCO3, 0.1mM EDTA in PBS). After ACK lysis, marrow was plated on 10cm tissue culture plates in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Media (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 10% FBS (Peak Serum, Wellington CO), 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 ug/ml streptomycin. Unless stated otherwise, cell culture media additives were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cells were incubated at 37°C/ 5% CO2 for 4h. After incubation, non-adherent cells were pelleted and resuspended in DMEM, 10%FBS, 15% L929 conditioned media, 10mM HEPES buffer, and 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 ug/ml streptomycin and plated for 7d at 37°C/ 5% CO2. Fresh media was added on d4 to supplement old media (no media removed). After 7d, macrophages were detached using TrypLE (ThermoFisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), counted and plated at 1×106 cells/ml overnight. The following day, macrophages were stimulated with either 0 ng/ml, 100 ng/ml, or 1000 ng/ml LPS (Derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, L8643); M1 polarization conditions: 100 ng/ml LPS + 50 ng/ml mIFNγ (M1) or M2 polarizing conditions: 20 ng/ml mIL-4 + 20 ng/ml mIL-13 (M2). Cytokines were obtained from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). RAW264.7 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, TIB-71). Cells were maintained in DMEM, 10%FBS, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 ug/ml streptomycin. RAW264.7 were polarized or treated with LPS as described for BMDMs. ID8p53−/− (ID8 clone F3) murine ovarian cancer cell lines were provided by Iain A. McNeish (University of Glasgow)(30). Cells were cultured in DMEM, 4% FBS, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 ug/ml streptomycin, and 1x ITS (5 μg/ml insulin, 5μg/ml transferrin and 5ng/ml sodium selenite). Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells and EL4 lymphoma cells were obtained from ATCC (CRL-1642, TIB-39) and were cultured in DMEM, 10% FBS, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 ug/ml streptomycin to prepare for injection.

Morphology induced by LPS stimulation

To investigate morphological differences, BMDMs were stimulated with LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, L8643) for 6h. Three mice were analyzed per genotype. After 6h of stimulation with LPS, 4 transmitted light fields were taken per mouse at 20x on an EVOS Cell Imaging System (ThermoFisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Cells were considered to have morphology associated with an inflammatory phenotype if they 1) had flattened themselves against the plate and gained an “omelette” appearance and 2) if they had a branched morphology designated by lamellipodia and filopodia. Cells that maintained rounded morphology or maintained an elongation phenotype associated with M2 polarization were counted towards the non-inflammatory total. The four fields were averaged per mouse as a percent of inflammatory cells to total cells and then these values were averaged per genotype.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (q-RTPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA), according to manufacturer’s protocol. RNA from primary lineage negative cells was isolated using an miRNeasy kit from Qiagen (Germantown, MD, USA). RNA was reversed transcribed to cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA). qPCR was performed using gene specific fluorescent probe assays for both miRNAs and mRNAs on a CFX96 C1000 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative gene expression was calculated using the comparative threshold cycle method. Sno202snRNA and Gapdh were used as housekeeping genes for miRNAs and mRNA, respectively. miRNA cDNA primers (5x) and qPCR primers (20x) were ordered from ThermoFisher Scientific. All other primers for qPCR were ordered from IDT (Coralville, Iowa). Unless noted otherwise all q-RTPCR analysis was performed with 3 or more experimental replicates and 3 technical replicates.

ELISA for TNF

BMDMs derived from wildtype and mirn23a−/− mice. Cells plated at a density of 1×106 cells/ml a day prior to used were treated with 1000 ng/ml of LPS. After 1, 6, 12, and 24h tissue culture supernatant was isolated for ELISA analysis. The media was subsequently centrifuged to remove any BMDMs that were dislodged, and the supernatant was carefully transferred to a new tube and frozen at −80 degrees Celsius until assayed. 100ul of conditioned media from (un)stimulated BMDMs were analyzed. BMDM supernatants were analyzed for TNF concentrations with a Ready Set Go ELISA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) kit per manufacture protocol.

Immunoblots

Whole cell lysates were prepared by lysing cells in RIPA buffer (50mM Tris pH7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% EDTA, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with 2x Halt protease inhibitor (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein was separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Protein concentration was determined using BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). 40–75ug of protein was used per lane. Antibodies to proteins of interest STAT6 (D3H4), phospho-STAT6 pY641 (D859Y), STAT3 (124H6) and β-actin (8H10D10) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) were used in western blots. Signals were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Analysis was performed on the ChemiDoc XRS+ system using Image Lab (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) or ImageJ (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) software.

Flow cytometry

The polarization of BMDMs was evaluated by flow cytometry. BMDM were prepared as described above from the bone of wildtype and mirn23a−/− mice. After 6d BMDMs were replated at 500,000 cells per well of a 6 well non-tissue culture plate. Cells for M0 and M2 polarization were replated in M-CSF (10% L929 conditioned media) containing media, whereas M1 polarized cells were plated in GM-CSF (10% HM5 conditioned media) containing media. 24h after replating M1 cells were treated with IFNγ and LPS and M2 cells were treated with IL-4 and IL-13 as described above for 12 or 24h. Single cell suspensions were prepared using TrypLE. Cell suspension were incubated with Fc Block (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) to block non-specific antibody binding. Cells were then incubated with antibodies to extracellular antigens, IA/IE, CD206, and CD38 (Biolegend) in PBS/ BSA. For detection of intracellular antigens cells were subsequently fixed and permeabilized with eBioscience Foxp3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (ThermoFisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) according to manufacturers’ protocol. After fixation and permeabilization cells were incubated with fluorochrome conjugated antibodies to iNOS, Arginase 1, and Egr-2 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA). Labeled cells suspensions were analyzed on a FC500 (Beckman Coulter, Pasadena CA) flow cytometer.

Macrophage killing assay

We plated 500,000 wildtype and mirn23a−/− BMDMs into each well of a 6-well plate in 2.5mls MCSF (L929) BMDM media. 24h later 1×106 EL4 cells/ well were added to BMDMs or as a control EL4 cells were plated alone. Cells were then cultured in the presence of absence of 20ng/ml LPS to activate macrophage tumoricidal killing. 48h later the non-adherent EL4 cells were collected and incubated with Annexin V-PE for flow cytometric analysis to assay cell viability.

ID8p53−/− co-culture with BMDMs

BMDMs were seeded at 1×106 cells/well of 6 well tissue culture (treated) plates. BMDMs were exposed to an equal number of ID8p53−/− (ID8 F3 Trp53−/− clone)(30) cells across 0.4um transwell inserts (Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY) for 24h. RNA was prepared and qRT-PCR was performed as described previously.

Animals

Mirn23a−/− mice were previously described(18). Wildtype and mirn23a−/− mice between 6–8 weeks of age were used for all experiments. For generation of BMDMs mice were euthanized in the euthanex chamber (Perotech, Markham, ON, Canada) in the Freimann Life Science Center (University of Notre Dame). Femurs and tibias were then isolated as a source of bone marrow. For tumor survival studies wildtype and mirn23a−/− C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with ID8p53−/− syngeneic ovarian tumor cells. In brief, 5×106 ID8p53−/− cells were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) into 8 wildtype and 8 mirn23a−/− mice. For Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) tumor studies, 6–10 week old mice were subcutaneously (s.c.) injected on their lower right flank with 3×105 cells in 100ul PBS. When tumors became palpable (typically 10 days post injection), tumor growth was monitored every three days and tumors were measured via caliper. Tumor volume was calculated as: Volume=0.52 x (width)2 x (length). For BMDM co-injection studies, 2.25×10e5 LLC cells were injected with either 7.5×10e4 wildtype or mirn23a−/− BMDMs (3:1 tumor to BMDM) as described above. For analysis of tumor associated macrophages, resected LLC tumors were mechanically minced and then incubated in RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 4 degrees with supplemented Collagenase IV (2500U/ml) (ThermoFisher Scientific) and DNase I (200U/ml) (Promega, Madison WI) for 1h. The resultant single cell suspensions were strained through 70um filters. To obtain the enriched immune cell fraction, the filtered suspension was separated via Ficoll-Paque at 805 x g for 20 minutes at 20 degrees Celsius. The immune cell fraction was carefully removed and prepared for flow cytometric analysis. Cells were stained with fluorochrome labeled antibodies recognizing CD11b, CD45, CD206, and F4/80 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Labeled cells suspensions were analyzed on a FC500 (Beckman Coulter, Pasadena CA) flow cytometer.

The University of Notre Dame IACUC policy for humane endpoints in animal experimentation were followed. Mice were visually monitored daily for signs of lethargy and abdominal distension. End points for euthanasia included lethargy, decreased motility, and cross-sectional abdominal diameter increase greater than 1/3. The use of mice in these experiments was approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine and University of Notre Dame IACUCs (Protocols 16–05-3180 (KCD) and 16–08-3312 (RD)).

RNA sequencing

Myeloid progenitors (Lin-kit+sca1-) were sorted from bone marrow on a FacsAria III. ACK lysed bone marrow was incubated with biotin labeled Lin cocktail antibodies (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, CA), Streptavidin-APCcy7, Sca1-FITC, c-Kit-APC. Sca1 and c-Kit antibodies were obtained from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). For each genotype (wildtype and mirn23a−/−) 4 separate RNA preps were prepared and used to build sequencing libraries. Each RNA preparation was prepared from sorted cells acquired from bone marrow isolated from 3 to 4 mice. M1/M2 polarized macrophages were prepared as described above. RNA was prepared from BMDMs generated from 3 unique animals for each genotype. BMDMs were washed 2x in PBS pH 7.4. Cells were subsequently lysed in TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) and RNA was isolated using Qiagen miRNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following manufacturer protocol. RNA-seq libraries were prepared at the University of Notre Dame Genomics and Bioinformatics Core Facility. Total RNA samples were diluted 5 times prior to analysis. Sample concentration was measured using Qubit RNA HS Assay Kit (PN: Q32855; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Total RNA was evaluated with Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 System and Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit (PN: 5067–1511; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Samples with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) of 7 or higher were qualified for library preparation. Total RNA input was normalized to 150 ng. Polyadenylated RNA molecules were selected for using NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (PN: E7490S/L; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). Enriched polyadenylated RNA was converted into an Illumina library using NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep with Sample Purification Beads (PN: E7775S/L; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and barcoded with NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Index Primers Set 1) (PN: E7335S/L; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) or NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Index Primers Set 2) (PN: E7500S/L; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). Indexed libraries were quantitated with Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (PN: Q32854; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Library quality assessment with Agilent DNA 7500 Kit (PN: 5067–1506; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The individual libraries were normalized, and equal molar amounts were multiplexed into a single pool. Molar concentration of the multiplex pool was determined with KAPA Library Quantification Kits for Illumina (PN: KK4824; KAPA Biosystems, Boston, MA). Materials used: NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep with Sample Purification Beads (PN: E7775S/L; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (PN: E7490S/L; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Index Primers Set 1) (PN: E7335S/L; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Index Primers Set 2) (PN: E7500S/L; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit (PN: 5067–1511; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Agilent DNA 7500 Kit (PN: 5067–1506; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), Qubit RNA HS Assay Kit (PN: Q32855; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (PN: Q32854; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and KAPA Library Quantification Kits for Illumina (PN: KK4824; KAPA Biosystems, Boston, MA). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500, paired-end, 75 total cycles to obtain greater than 20 million reads per sample. Reads were aligned to the human genome (hg19) using STAR (PMC3530905). Gene level expression was calculated (Fragments per Kilobase per Million-FPKM) using Cufflinks (PMC3146043) and differentially expressed genes identified using DE-seq (PMC3218662). For all algorithms, default parameters were utilized unless otherwise noted. Pathway analysis and upstream regulator analysis was performed using Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA, QIAGEN Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuitypathway-analysis), Biojupies (https://biojupies.cloud/), and Broad Institute Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) software (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). RNA-seq data is accessible by querying the accession numbers GSE160214 and GSE159762 at NCBI GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Statistical analysis

Statistical data is presented as +/− SEM. Differences between sample groups were determined by performing an unpaired Student’s t-test. Analysis was performed in Microsoft excel and using PRISM software, version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Loss of mirn23a in myeloid progenitor cells downregulates inflammatory signaling.

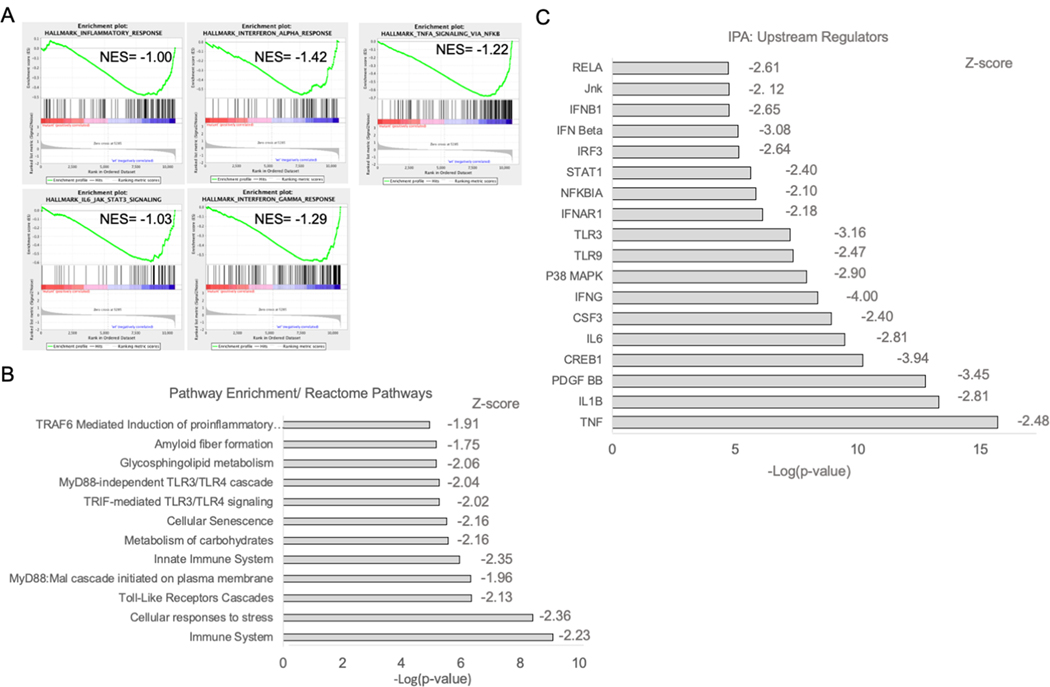

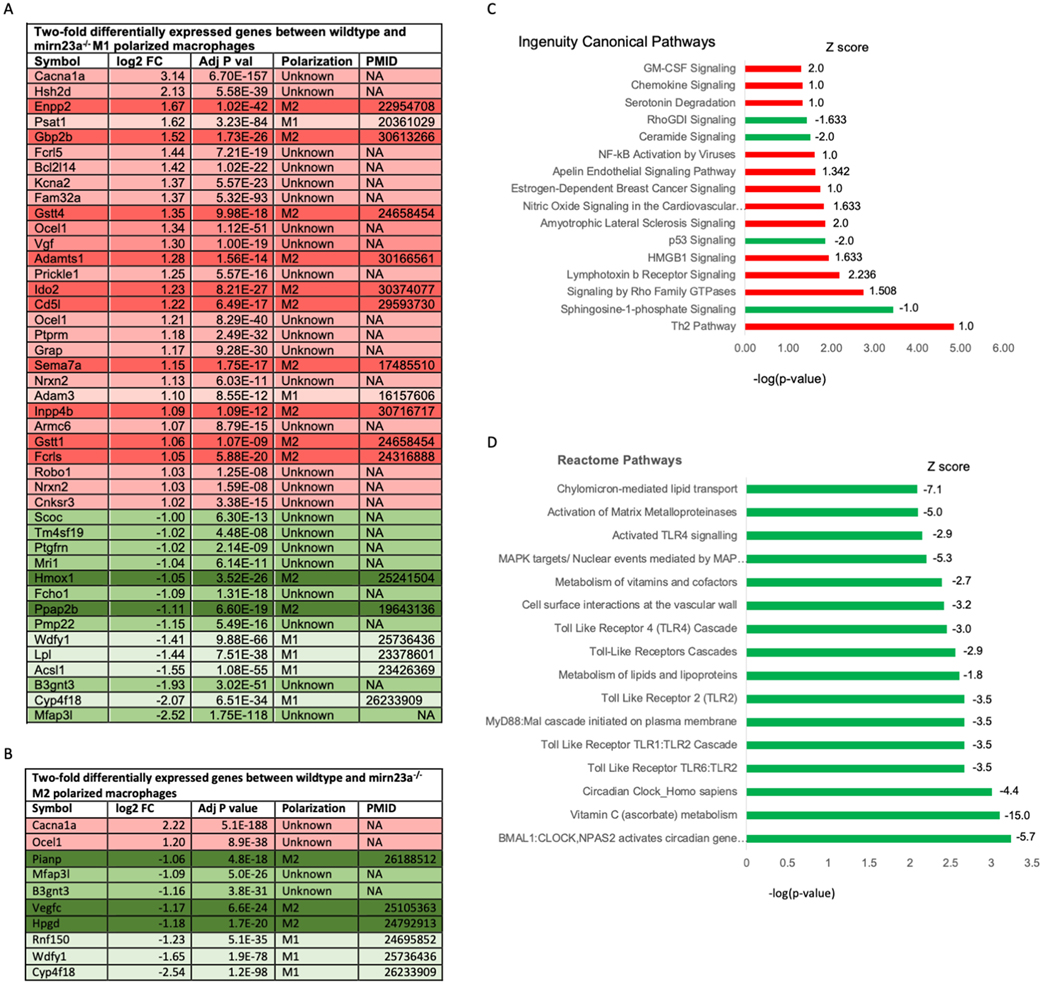

Previously we observed that mice with homozygous germline null mutations in mirn23a alleles results in skewed differentiation of HSPCs toward B lymphopoiesis at the expense of myelopoiesis(18). Mirn23a miRNAs agonize the Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3 kinase)/ Akt pathway and antagonize BMP4/ Smad signaling contributing to their promotion of myeloid development(19). To identify additional mirn23a targets that contribute to committing HSPCs to myelopoiesis, we isolated RNA from wildtype and mirn23a−/− myeloid progenitors (Lin-Sca1-Kit+) and performed RNA-seq analysis. Genes that were either significantly upregulated or downregulated 2-fold are shown in Tables I and II respectively. When we performed pathway analysis on differentially expressed genes, surprisingly, we observed that loss of mirn23a resulted in the downregulation of several inflammatory pathways (Fig 1). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)(31) querying the Hallmark gene sets revealed that inflammatory response genes were enriched in wildtype cells compared to mutant (Fig 1A). Specifically, Interferons Class I and II, TNF, and IL-6 signaling were downregulated in mutant cells as evaluated by GSEA. Consistent with the GSEA, querying the Reactome pathway database(32) demonstrated that TLR signaling and immune system pathways were downregulated in the absence of mirn23a(Fig 1B). Lastly, we analyzed the differentially expressed genes with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, Qiagen)(33), Upstream regulator analysis identifies upstream regulators that putatively explain observed gene expression changes in expression datasets. IPA revealed inhibition of inflammatory signaling regulators in mutant cells (Fig 1C). Molecules/stimuli/pathways with z scores <−2.0 are considered to be inhibited. TLR, Interferon and activation of NF-κB transcription complexes were all significantly downregulated in the mirn23a−/− myeloid progenitor datasets. The analysis also revealed downregulation of p38 and JNK stress transducing MAPK activity, which are responsive to inflammatory signals(34).

Table I.

Two-fold upregulated genes between wildtype and mirn23a−/− Myeloid Progenitors.

| Gene | log2 FC | Adj P Val |

|---|---|---|

| Adgrg5 | 4.60 | 4.35E-53 |

| Ftl1-ps1 | 3.59 | 3.86E-11 |

| Ccr1 | 2.40 | 1.38E-05 |

| Inpp4b | 2.36 | 2.94E-22 |

| Mmp9 | 2.19 | 7.74E-03 |

| Fcer1a | 2.03 | 2.33E-06 |

| Ly6g | 1.95 | 2.17E-02 |

| Ccnb1ip1 | 1.88 | 1.20E-02 |

| Csrp3 | 1.85 | 1.31E-06 |

| Kifc3 | 1.85 | 2.93E-11 |

| Ltf | 1.80 | 3.51E-02 |

| Ear6 | 1.71 | 2.05E-02 |

| Inhba | 1.69 | 4.44E-02 |

| Ear1 | 1.53 | 2.83E-02 |

| Tex15 | 1.51 | 1.71E-03 |

| Dsp | 1.47 | 1.71E-03 |

| Cldn1 | 1.47 | 3.52E-02 |

| Ifnlr1 | 1.45 | 3.56E-03 |

| Ifitm6 | 1.43 | 1.08E-02 |

| Ear2 | 1.42 | 2.40E-02 |

| Ccdc102a | 1.42 | 5.67E-09 |

| Slc4a1 | 1.42 | 4.27E-04 |

| Aldh3b2 | 1.36 | 1.71E-06 |

| Cap2 | 1.28 | 2.33E-04 |

| Gm8113 | 1.23 | 7.19E-03 |

| Sdc2 | 1.17 | 5.09E-05 |

| Fn3k | 1.13 | 3.98E-03 |

| Cnnm1 | 1.12 | 2.13E-04 |

| Eya4 | 1.11 | 2.53E-04 |

| Pirb | 1.08 | 9.82E-03 |

| Rasgrp4 | 1.08 | 2.70E-02 |

| Tcaf1 | 1.07 | 8.11E-04 |

| Olfr414 | 1.06 | 1.04E-02 |

| Hbb-bs | 1.02 | 3.34E-03 |

| Cacna1g | 1.02 | 6.63E-04 |

Table II.

Two-fold downregulated genes between wildtype and mirn23a−/− Myeloid Progenitors.

| Gene | log2 FC | Adj P Val |

|---|---|---|

| Clgn | −2.23 | 2.38E-10 |

| Atf3 | −1.77 | 1.67E-02 |

| Gm20481 | −1.49 | 3.82E-05 |

| Gm21887 | −1.46 | 1.09E-07 |

| Ptgs2 | −1.44 | 1.66E-03 |

| Fosb | −1.38 | 4.04E-06 |

| Mid1 | −1.37 | 1.52E-02 |

| Gm10252 | −1.29 | 1.78E-02 |

| Plk2 | −1.25 | 5.06E-03 |

| Tmem74 | −1.20 | 4.19E-03 |

| Cldnd2 | −1.17 | 3.35E-03 |

| Dusp1 | −1.16 | 6.59E-07 |

| Fos | −1.15 | 1.23E-10 |

| Nebl | −1.12 | 4.93E-04 |

| Rnase10 | −1.11 | 2.46E-03 |

| Klf2 | −1.09 | 2.56E-04 |

| Filip1 | −1.08 | 5.29E-03 |

| Ccl3 | −1.06 | 1.67E-03 |

| Trib1 | −1.06 | 1.67E-02 |

| Dusp2 | −1.05 | 1.43E-06 |

| Gla | −1.04 | 5.60E-10 |

| Wdfy1 | −1.04 | 2.36E-05 |

| Rnf150 | −1.03 | 7.59E-05 |

| Dmkn | −1.03 | 1.26E-03 |

| Usp44 | −1.02 | 2.62E-04 |

| Mri1 | −1.02 | 3.18E-11 |

| Gm47283 | −1.02 | 7.97E-06 |

| Egr1 | −1.01 | 4.04E-03 |

Fig 1. RNA-seq analysis of RNA isolated from myeloid progenitors reveals that mirn23a loss downregulates inflammatory signaling.

RNA was isolated from wildtype (n=4) and mirn23a−/− (n=4) bone marrow myeloid progenitors (Lin-Sca1-cKit+) and subjected to RNA-seq analysis. A) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) plots of wildtype vs. mirn23a−/− myeloid progenitor gene expression interrogating the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) Hallmark Gene Set. B) Differentially expressed genes were used to interrogate the Reactome Pathway analysis using BioJupies software. C) Differentially expressed genes were used to identify upstream regulators affected by loss of mirn23a using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software.

Mirn23a−/− decreases inflammatory response to LPS in BMDMs

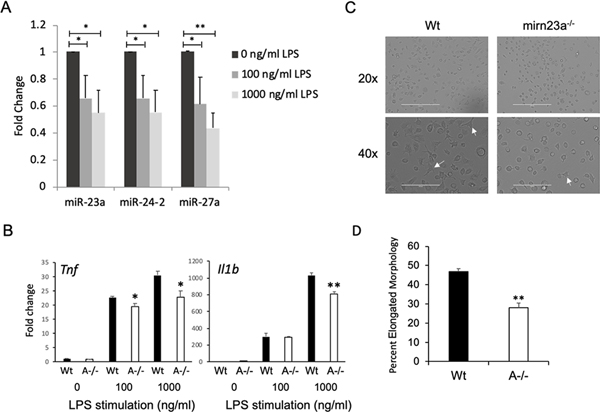

The RNA-seq data suggested that macrophages deficient in mirn23a have reduced responses to inflammatory signaling. We generated bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) from wildtype and mirn23a−/− mice to examine the role of cluster miRNAs in regulating the inflammatory functions of these critical regulators of immune function. In agreement with previous reports(20, 27, 29, 35), we observed that inflammatory molecule/ TLR4 ligand, LPS, decreased the expression of all three mirn23a miRNAs in BMDM after 24h of treatment (Fig 2A). When BMDMs from wildtype and mirn23a−/− were challenged for 24h with 0, 100, or 1000 ng/ml of LPS, we observed significantly decreased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines Tnf and Il1b with the highest concentration of LPS in mirn23a−/− BMDMs compared to wildtype (Fig 2B). Consistent with this decrease in production of inflammatory cytokines, we observed after 6h LPS stimulation, mirn23a−/− BMDMs have delayed acquisition of an elongated morphology commonly gained upon exposure to inflammatory stimuli compared to wildtype (Fig 2C, D)(36, 37).

Fig 2. Mirn23a Bone Marrow Derived Macrophages (BMDM) have a reduced response to bacterial derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mirn23a miRNA (miRs-23, −24–2, −27a) expression in wildtype BMDMs treated with LPS for 24h. B) Expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines Tnf and Il1b in LPS treated wildtype (Wt, n=3) and mirn23a−/− (A−/−, n=3) BMDMs. C) Representative bright-field Images of Wt (n=3) and A−/− BMDMs (n=3) treated with 1000ng/ml LPS for 6h. Arrows indicate cells displaying an elongated morphology associated with a response to LPS. D) Quantification of the percentage of cells demonstrating elongated morphology. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). *(p<0.05), ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.001).

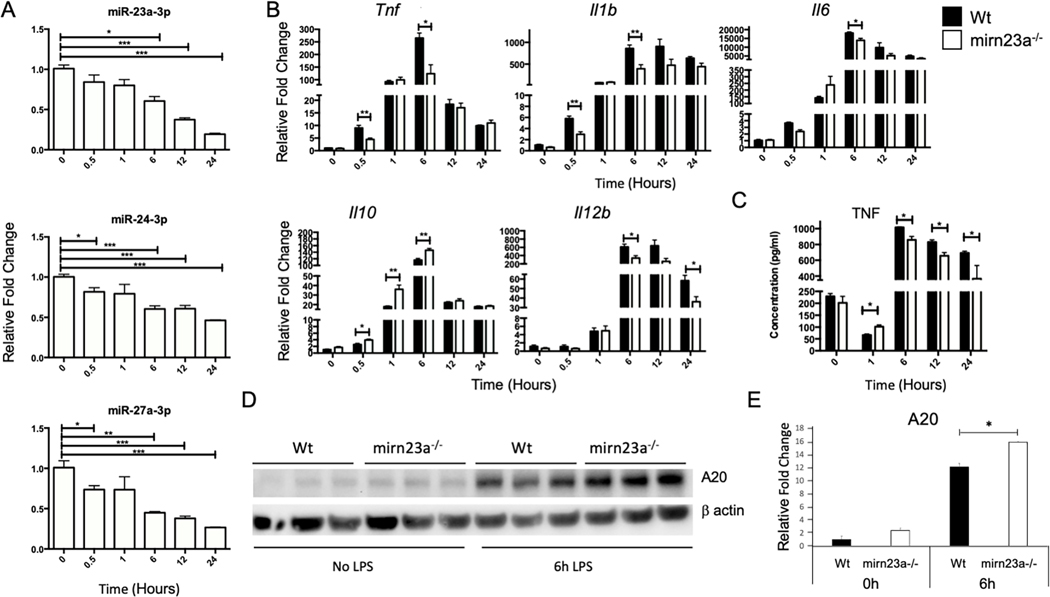

Next we performed a time course of gene expression after LPS treatment of BMDMs. After 6h of LPS treatment, we observed significantly decreased expression of miRs-23a, −27a and −24 (Fig 3A). Downregulation of miR-24 is not as robust likely due to contribution of miR-24 produced from the mirn23a paralog gene mirn23b (the two genes produce identical mature miR-24–3p). In addition to examining miRNA expression we quantified the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines Tnf, Il1b, Il6, Il12b and anti-inflammatory cytokine Il10 (Fig 3B). Significant differences for all cytokines were observed after 6h of treatment. For Tnf and Il1b there were a significant decrease in expression detected after only 0.5h. An ELISA was performed on conditioned media for the presence of TNF and in agreement with gene expression analysis we observed decreased concentration of TNF in the media obtained from LPS treated mirn23a−/− cell compared to wildtype BMDMs (Fig 3C). For the anti-inflammatory gene Il10 we observed more robust expression in mutant macrophages 0.5h after LPS treatment which continued for up to 6h post-treatment (Fig 3B). Lastly protein expression of LPS induced/ anti-inflammatory protein A20 (coded for by Tnfaip3) was examined by immunoblot (Fig 3D, E). A20 is required for terminating TLR signaling in macrophages and protects mice from LPS induced endotoxic shock(38). Expression of miR-23a inhibitors and mimics have demonstrated A20 to be a miR-23a target in macrophages(39). Basal levels of A20 were ~2 fold higher in mirn23a−/− BMDMs. Six hours after LPS treatment of wildtype and mirn23a−/− macrophages, we observed induction of A20 in both genotypes. A20 in LPS induced macrophages was modestly increased (~1.3 fold) in mutant cells compared to wildtype (p<0.015). The effect of mirn23a loss on cytokine expression and A20 protein levels after LPS treatment of macrophages is consistent with the decreased inflammatory signaling pathways we observed with myeloid progenitors.

Fig 3. Time-course of cytokine expression in LPS treated Bone Marrow Derived Macrophages (BMDM).

BMDMs were treated with 1000 ng/ml of LPS for the indicated times and RNA harvested for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mirn23a miRNA relative expression in wildtype (Wt) BMDMs treated with LPS (n=3). B) Relative expression of cytokines in LPS treated Wt (n=3) and mirn23a−/− (A−/−, n=3) BMDMs. C) BMDMs (Wt, n=3) and mirn23a−/− (A−/−, n=3) were treated with 1000 ng/ml of LPS for the indicated times and tissue culture supernatant isolated for ELISA analysis. D) Whole cell lysates were prepared from Wt (n=3) and A−/− (n=3) BMDMs treated with 1ug/ml LPS for the indicated times. Lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting. Blots were probed with antibodies to A20 and β-actin. A20 expression normalized to β-actin. E) Quantitated relative expression of A20 levels in Wt cells prior to LPS stimulation. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). *(p<0.05), ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.001).

Mirn23a regulates macrophage polarization

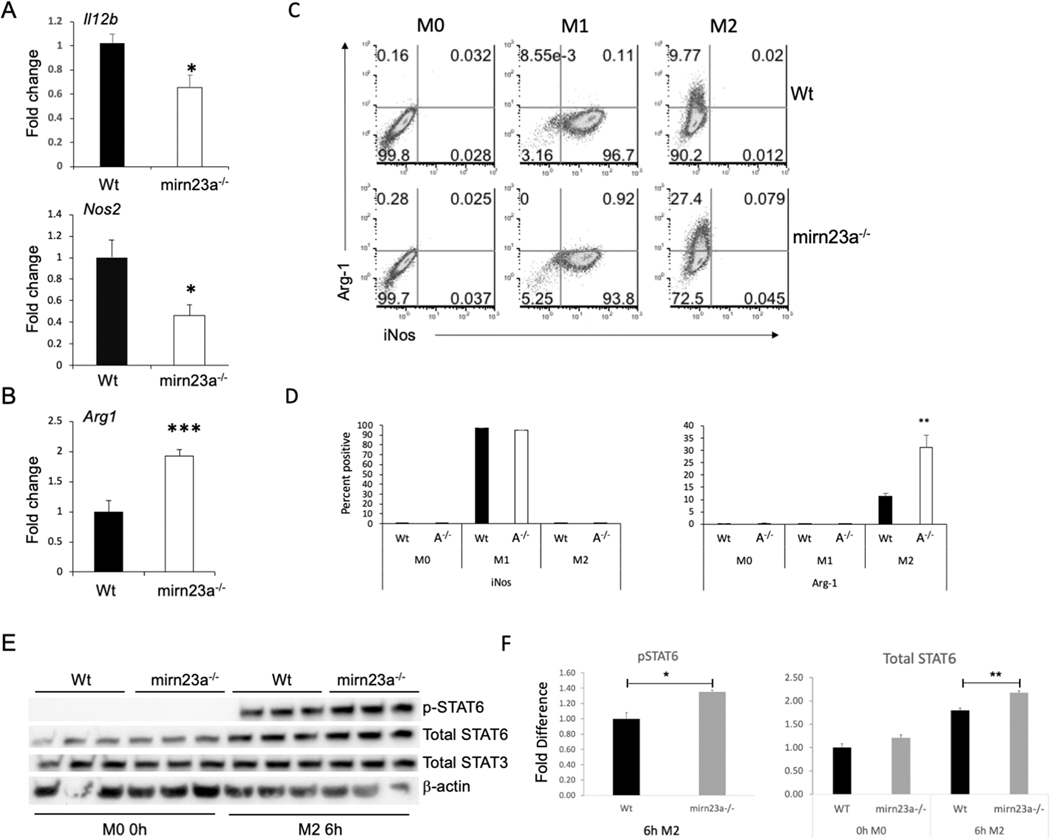

The decreased inflammatory response to LPS suggested that mirn23a miRNAs regulate macrophage polarization. To investigate this, BMDMs were polarized with M1 (LPS and IFNγ) and M2 (IL-4 and IL-13) conditions for 24h. To evaluate the polarization status of the cells, expression of Il12b, Nos2 and Arg1 were assayed. IL-12β is a pro-inflammatory cytokine induced by the M1 stimuli LPS and IFNγ(40). iNos (protein product of nos2) and Arg-1 are involved in arginine metabolism(41). When macrophages are polarized to M1, arginine is broken down by iNos to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) whereas, in M2 macrophages, arginine is broken down into ornithine and other metabolites that are used for tissue repair. In accordance with our data from Figs 2, 3, mirn23a−/− BMDMs polarized to M1 had significantly decreased expression of pro-inflammatory genes Il12b and Nos2 compared to wildtype (Fig 4A). Mirn23a−/− M2 polarized BMDMs had significantly increased expression of M2 associated gene Arg1 compared to wildtype (Fig 4B). Mirn23a−/− M1 polarized BMDMs had ~2-fold decrease in Nos2 compared to wildtype polarized cells and mutant M2 cells had ~2-fold increase in Arg1 compared to wildtype. We next examined the polarization of wildtype and mirn23a−/− macrophages by flow cytometry assaying expression of iNOS (M1) and Arg-1(M2) protein (Fig 4C). BMDMs were prepared from both genotypes and polarized for 12h. Naïve macrophages were not positive for iNOS or Arg-1 expression. No significant genotype specific differences in iNOS positive cells were observed with M1 polarization which resulted in over 90% of cells expressing detectable iNOS in both genotypes. However, when cells were M2 polarized we observed ~ 3-fold more Arg-1+ cells in the mirn23a−/− cells compared to wildtype (Fig 4D). Similar results were obtained when we examined polarization after 24h. We also examined polarization of macrophages with 2 additional panels CD38 (M1) vs. EGR2 (M2) and IA/IE (M1) vs. CD206 (M2)(42–44). In agreement with what we observed with iNOS positive cells we did not observe any significant difference in the expression of IA/IE or CD38 on M1 BMDMs (Fig S1). However, we did observe ~2-fold increases in EGR-2+ and CD206+ mirn23a−/− macrophages compared to wildtype under M2 polarization conditions. The discrepancy in Nos2 levels being decreased in mirn23a cells as assayed by q-RT-PCR, but no difference observed in percent positive iNOS+ cells assayed by flow cytometry is likely due to decreased abundance in Nos2 transcripts per cell.

Fig 4. Loss of mirn23a reduces M1 polarization and enhances M2 polarization of BMDMs.

Wildtype (Wt) and mirn23a−/− (A−/−) BMDMs were polarized to M1 (IFNγ/ LPS) and M2 (IL-4/ IL-13) for 24h. RNA was harvested and analyzed by qRT-PCR for relative expression of A) M1 associated genes Il12b (n=3 each genotype) and Nos2 (n=8 each genotype), and B) M2 associated gene Arg1(n=6 each genotype). C) Wt (n=3) and mirn23a−/− (n=3) BMDMs polarized to M1 (24h pre-treat GM-CSF followed by 12h IFNγ/ LPS) and M2 (M-CSF/ IL-4/ IL-13) for 12h were collected and assayed for expression of M1 protein iNos and M2 protein Arg-1 by flow cytometry. D) Average positive cells for iNOS and Arg-1 protein expression. E) Whole cell lysates were prepared from Wt and mirn23a−/− BMDMs that were unstimulated or stimulated with IL-4 and IL-13 (M2 conditions) for 6h. Proteins blots were prepared and probed with antibodies to total STAT6 and STAT3, phospho-STAT6 and β-actin. F) Relative total STAT6 and phospho-STAT6 were quantified. Protein loading was normalized to total STAT3 which was not significantly affected by cytokine stimulation. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). *(p<0.05), ** (p<0.01) and *** (p<0.001).

To further analyze the effect mirn23a loss had on M2 polarization we examined the activation of STAT6 downstream of the M2 polarizing conditions (IL-4, IL-13). IL-4 activates STAT6 through receptor activation of JAK3 kinase which results in phosphorylated STAT6 translocating to the nucleus where it activates genes associated with mouse M2 macrophages including Arg1, macrophage mannose receptor 1 (Mrc1; CD206)(45, 46). STAT6 and JAK3 have been shown to be direct targets of mirn23a miRNAs. Protein extracts were prepared from unstimulated (M0) BMDMs derived from genotypes and BMDMs treated with IL-4 and IL-13 (M2 conditions) for 6h. Modest but significant increases in total STAT6 (p<0.007) and phospho-STAT6 (p<0.04) were observed in 6h M2 polarized mirn23a−/− BMDMs compared to wildtype (Fig 4E, F). There was also a modest increase observed in unstimulated BMDMs but this was not quite significant with a p value of less than 0.08. No changes were observed in total levels of STAT3.

Previously work investigating the mirn23 cluster only examined macrophage polarization when a single cluster miRNA is overexpressed or knocked down, and these studies have yielded contradictory results(23–26, 47). Here we overexpressed the mirn23a cluster (23aCl) in RAW264.7 murine macrophages. Mirn23a overexpression was confirmed by examining miR-23a, −24–2 and −27a levels. All miRNAs were expressed in the 23aCl cells at least 4-fold above expression in the control cells (stably infected with MSCV virus) (Fig S2A). We polarized the MSCV and 23aCL RAW264.7 cells for 24h with either M1 or M2 conditions. RNA was harvested and gene expression associated for the M1 and M2 phenotype was examined. M1 polarized 23aCl macrophages had approximately 2-fold higher expression of Tnf and Nos2 compared to MSCV cells; whereas M2 polarization resulted in over a 2-fold decrease in Arg1 and an over 80% decrease in Il10 expression (Fig S2B). We also observed that LPS treatment alone of 23aCL macrophages resulted in a decrease in Il10 transcription (Fig S2C).

Mirn23a−/− polarized BMDMs are enriched for M2 programs

To further characterize mirn23a regulation of macrophage polarization, we performed RNA sequencing on M1 and M2 polarized wildtype and mirn23a−/− BMDMs. Transcripts differentially regulated greater or less than 2-fold (1.0 log2 fold change) in mirn23a−/− M1 and M2 polarized BMDMs are shown in Figure 5A, B. Strikingly, the number of genes with significant (p<0.05) 2-fold changes in our M1 dataset is 4-fold higher than the 2-fold changed genes in our M2 dataset. 43 unique genes were differentially expressed over 2-fold in M1 mutant macrophages compared to wildtype with 29 upregulated and 14 downregulated. Of the 29 upregulated genes 10 genes are known to be associated with M2 polarization with only 2 associated with M1 polarization. Of the 14 repressed genes, 4 are reported to be associated with M1 polarization and 2 (Hmox1 and Ppap2b) with M2 polarization. Although Hmox1 and Ppap2b are described to be associated with M2 polarization, in our hands they are expressed 8.0 and 4.6-fold higher respectively in wildtype M1 cells compared to M2 cells. We found that 10 genes were differentially expressed in mirn23a−/− M2 macrophages by at least 2-fold compared to wildtype. Eight of these genes were repressed. Additionally, 4/10 of the M2 differentially expressed were also differentially expressed with M1 conditions. Several of the up and down-regulated targets between the M1 and M2 datasets are the same, suggesting that mirn23a regulates general macrophage functions as well as polarization specific functions.

Fig 5. Pathway analysis of RNA-seq data obtained from wildtype and mirn23a−/− M2 polarized BMDMs.

RNA-seq analysis was performed on RNA isolated from wildtype (n=3) and mirn23a−/− BMDM (n=3) after polarization for 24h with M2 conditions. Two-fold differentially expressed genes between wildtype and mirn23a−/− BMDMs. A) M1 polarized B) M2 polarized. Red/ green indicates up and down regulated genes respectively. Dark and light shades indicate gene product association with M2 or M1 polarizations respectively. Intermediate shading indicates that nothing in the literature supports a role in macrophage polarization. C) IPA canonical pathway analysis. Pathways with a p<0.05 and with a z-score greater than or equal to 1.0 or less than or equal to −1.0 are shown. Red bars indicate predicted upregulated pathways and green bars indicate downregulated pathways in mirn23a−/− M2 macrophages. D) Top 16 downregulated Reactome pathways in mirn23a−/− M2 macrophages compared to wildtype macrophages ranked by p-value.

We performed canonical pathway analysis with IPA software (Qiagen) to analyze differentially expressed genes in M1 polarized macrophages. Pathways with a p<0.05 and with a z-score greater than or equal to 1.0 or less than or equal to −1.0 are shown in Figure 5C. As evaluated by z-score the most highly activated pathway is Lymphotoxin β receptor signaling. Activation of Lymphotoxin β receptor downregulates inflammatory signaling through inducing cross-tolerance to TLR4 and TLR9 ligands(48). The two most downregulated pathways were ceramide and p53 signaling. Ceramide is composed of sphingosine and a fatty acid, which can act as a cell signaling molecule through activation of phosphatase 2A, p38, JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK), AKT, protein kinase Cζ and survivin. It was shown to have anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory properties. p53 is known for its role as a tumor suppressor, however it also regulates inflammatory signaling in macrophages(49). P53 activity increases when macrophages are polarized to the M2 leading to reduced expression of M2 genes. Macrophages lacking p53 express higher levels of M2 genes during M2 polarization(49).

Differential gene expression between wildtype and mirn23a−/− M1 polarized macrophages was examined for enrichment or de-enrichment of Reactome pathways. Of the top 16 significantly downregulated pathways in mutant M1 macrophages compared to wildtype, we observed that 7 of these pathways were related to TLR signaling (Fig 5D). The downregulation of TLR pathways is similar to what we observed in myeloid progenitors freshly isolated from bone marrow (Fig 1B).

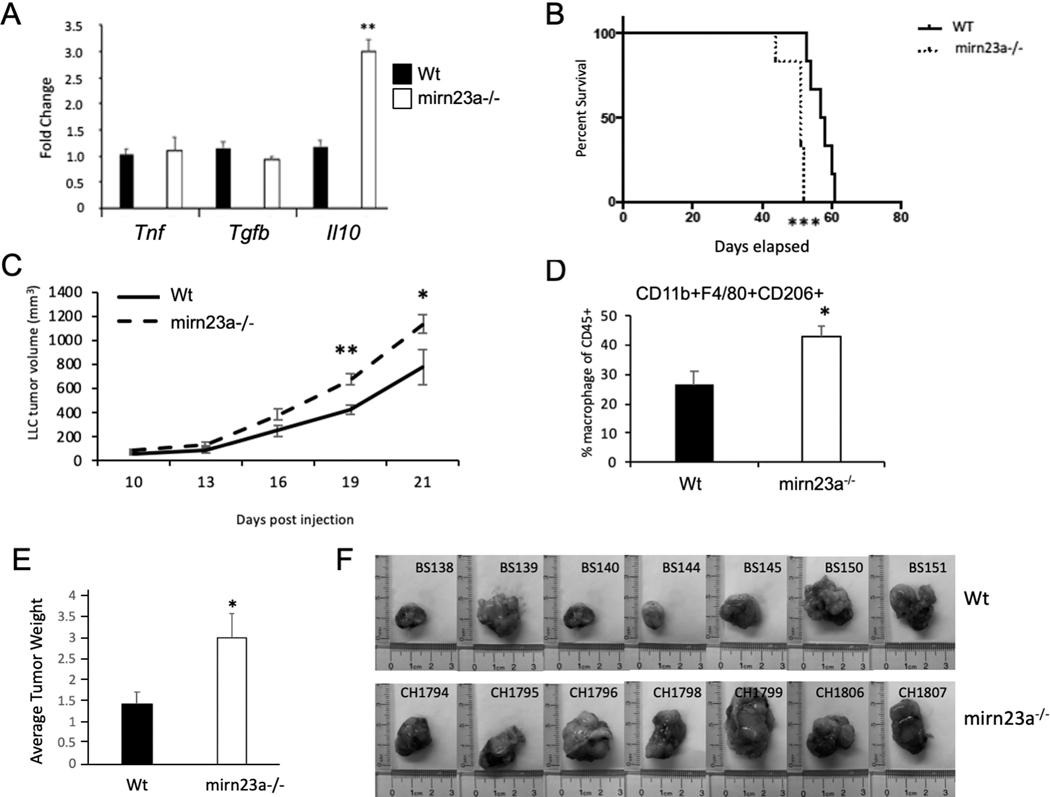

Physiological consequences of mirn23a expression

In vitro evaluation of macrophages revealed that mirn23a miRNAs repress or limit M2 polarization. It is not clear though if these effects on polarization are significant enough to affect macrophage function in vivo. Due to their inflammatory plasticity, macrophages are involved in many disease states including anti-tumor immunity(5, 50–52). In the tumor microenvironment, tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) acquire a M2-like phenotype that promotes tumor growth and migration, as well as suppressing the local immune environment to assist the tumor in evading an immune response(51). Increased M2 polarized TAMs in the tumor microenvironment is associated with poorer prognosis for several tumor types(53). Tumor cells secrete factors that polarize macrophages to an immunosuppressive M2 phenotype(54). To M2 polarization of TAMs contributes to the progression of tumor growth in the ID8 syngeneic murine tumor model of ovarian cancer(55). Reprogramming of macrophages to an M1 phenotype restricts the growth of ID8 tumors and ablating macrophages in the ID8 tumor microenvironment slows tumor growth. In our study we used an ID8 line deficient in Trp53 (ID8p53−/−) that elicits an immune response similar to human high grade serous ovarian cancer with increased CD11b+ myeloid cell infiltrates compared to parental ID8 cells(30). Several different tumor cell lines including ID8 have been shown to polarize macrophages to an anti-inflammatory state through the release of cytokines and exosomes(54, 56–59). To determine if loss of mirn23a expression in macrophages enhances M2 polarization by tumor cells as we have observed with recombinant cytokines, we performed transwell assays with ID8p53−/− mouse ovarian cancer cells and BMDMs. Cells in the transwell assay do not have direct contact and therefore are influenced by secreted factors. BMDMs from wildtype and mirn23a−/− mice were incubated with ID8p53−/− cells for 24h. Co-cultured macrophages had no significant differences in expression of Tnf or Tgfb, however, there was significantly increased expression of the potent anti-inflammatory cytokine Il-10 (Fig 6A). These data suggest that regardless of the stimuli, mirn23a−/− macrophages have a bias towards anti-inflammatory M2 polarization states.

Fig 6. Syngeneic tumors generated in mirn23a−/− mice are more aggressive than tumors generated in wildtype mice.

A) Wildtype (Wt, n=3) and mirn23a−/− (A−/−, n=3) BMDMs were plated onto 6 well plates. Transwell inserts with ID8p53−/− mouse syngeneic ovarian cancers were placed in the wells so soluble factors could diffuse. After 24h of culture RNA was prepared from BMDM and qRT-PCR used to analyze expression of the indicated cytokines. B) Wt (n=6) and mirn23a−/− (n=6) were subjected to intraperitoneal (IP) injection of ID8p53−/− tumor cells. Survival of mice was observed and a Kaplan-Meier curve generated. C) Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of wt (n=6) and mirn23a−/− (n=8) mice. Tumor volume was measure by calipers after injection. D) After 21 days tumors were isolated and tumor associated macrophage populations assayed by flow cytometry using cell surface markers CD45, CD11b, F4/80, and CD206. E) In a 2nd independent experiment wt (n=7) and mirn23a−/− (n=7) mice were s.c. injected with LLC cells and tumors isolated and weighed after 21d. Average weight of tumors isolated from Wt and mutant mice is shown. Significance of survival data determined by Log Rank test. Other data examined by student t-test. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). *(p<0.05), ** (p<0.01), *** (p<0.001).

To determine if the increased M2 polarization of mirn23a−/− macrophages by ID8p53−/−cells impacts tumor growth, we generated syngeneic tumors using ID8p53−/− cells in wildtype and mirn23a−/− mice with a C57BL/6 background. Since we demonstrated that mirn23a expression impacts macrophage polarization and other immune cells, we anticipated that tumor growth or burden would be impacted by mirn23a expression. Specifically, we hypothesized that tumor growth in mirn23a−/− mice would decrease live span compared to their wild type counterparts due to immune suppression. Six mice for each genotype were examined. Mice were euthanized when tumor burden was high, and mice were moribund. Mirn23a−/− mice exhibited a median survival of 51 days; the mean survival for wildtype mice was 57.5 days (Fig 6B). A log rank (Mantel-Cox) test determined that this difference was significant with a p value of 0.0008. Additionally, a Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test determined that the difference was significant with a p value of 0.0015. These results indicate that the presence of mirn23a in the tumor microenvironment impacts ovarian tumor growth.

The i.p. injected ID8p53−/− mimics ovarian cancer metastasis as the tumor cells spread through the peritoneal cavity and hundreds of tumors develop on the abdominal membranes and organs (REF). Additionally, mice with ID8p53 tumors develop extensive ascites; therefore, quantitating tumor mass or volume is difficult, so we performed a subcutaneous (s.c) tumor model in order to better examine tumor growth. Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) cells were injected s.c. into wildtype and mirn23a−/− mice and the tumor growth was monitored. LLC tumors grew quicker in mirn23a−/− mice with significantly increased tumor volumes compared to wildtype at d19 and d21 (Fig 6C). Mice were euthanized at d21 and tumors collected to evaluate size and prepare single cell suspensions for flow cytometric analysis. Single cell tumor suspensions demonstrated an increased percentage of CD11b+F4/80+CD206+ macrophages in the immune cell fraction of tumors generated in mirn23a−/− mice. (Fig 4C). CD206 is a marker of M2 macrophages. Tumors isolated from mirn23a−/− mice had an average weight ~2-fold higher compared to tumors isolated from wildtype animals (Fig 6E, F).

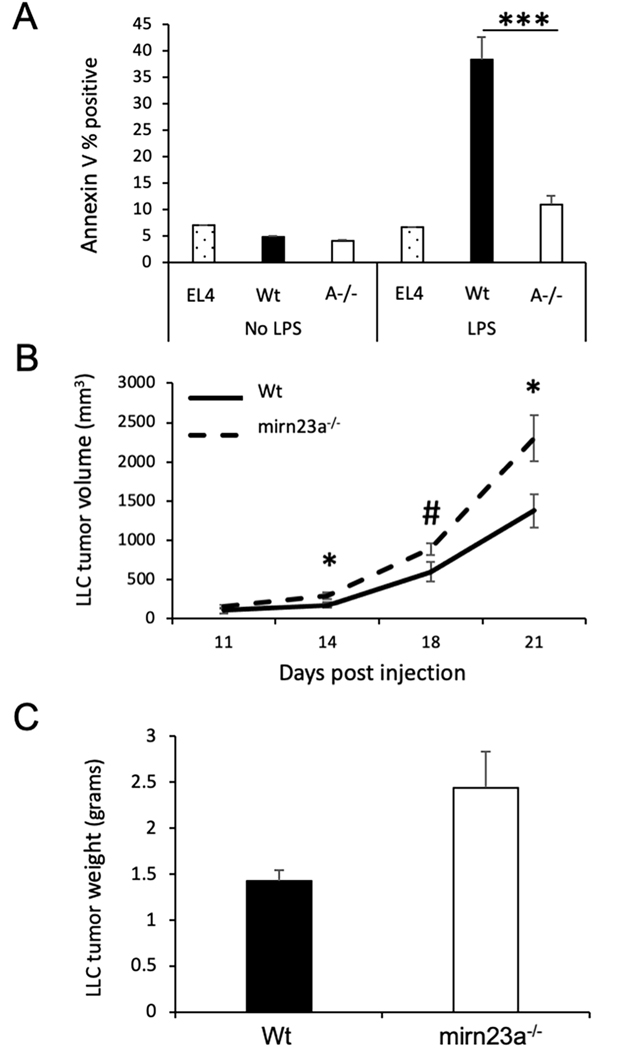

mirn23a−/− macrophages promote tumor growth.

Increased tumor associated macrophages in mirn23a derived tumors suggested that the more aggressive tumor growth could be due (or partially due) to loss of mirn23a in macrophages. To examine this, we first evaluate the tumor killing activity of mirn23a−/− macrophages. Wildtype and mutant BMDMs co-cultured with syngeneic EL4 lymphoma cells in the presence and absence of LPS which activates the cytotoxic activity of the macrophages(60). After 72h, the EL4 suspension cells were removed and cell death assayed by Annexin V binding using flow cytometry. In the absence of LPS, cell death was similar between EL4s cultured in the absence of BMDMs and cells cocultured with either wildtype or mirn23a−/− BMDMs (Fig 7A). LPS had no effect on EL4 cell cultured alone. However, LPS induced ~8-fold increase in EL4 cell death mediated by wildtype BMDMs, but only ~2-fold increase in EL4 cell death in mirn23a−/− BMDM co-cultures. The results suggest that mirn23a−/− macrophages have reduced tumor cell killing activity compared to wildtype.

Figure 7. Mirn23a macrophages enhance tumor growth.

A) Nonadherent EL4 cells were plated alone (3 technical replicates) or with Wildtype (Wt, n=3) and mirn23a−/− (A−/−, n=3) bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) in the presence and absence of LPS. After 48h of co-culture, EL4 cells were removed and assayed for cell death by annexin V binding. B) Wt mice were subcutaneously injected with Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) cells and either Wt (n=6) or mirn23a−/− (n=6) BMDMs. Tumor volume was measure using calipers over time. C) 21d after injection tumors were isolated and weighed. Average weight of tumors generated in the presence of Wt and mirn23a−/− BMDMs is shown. *(p<0.05), *** (p<0.001), and # (p=0.053).

We next examined whether mirn23a−/− macrophages alone could enhance the growth of syngeneic tumors. Several studies have previously shown that co-injection of BMDMs with syngeneic tumor cells affect tumor growth in vivo(61–63). M2 macrophages specifically have been shown to promote the in vivo growth of syngeneic LLC tumors(64). LLC cells were co-injected s.c. with either wildtype or mirn23a−/− BMDMs into wildtype C57BL/6 mice. Tumor cell/ macrophage injected mice were examined as previously done for LLC injections into wildtype and mutant mice. Tumor volumes were observed to be significantly increased in mice receiving mirn23a−/− macrophages at days 14, 18, and 21. At 21d post-injection tumors were isolated and weighed. Tumors derived in mice receiving mirn23a−/− BMDMs on average weighed more than tumors derived from mice receiving wildtype BMDMs. The difference in average weight was not quite significantly different with a p value of 0.064. These results imply that mirn23a deficiency in macrophages contributes to the enhanced tumor growth we observed when we transplanted LLC cells into mirn23a−/− mice (Fig 6).

Discussion

RNA-seq data demonstrated that myeloid progenitor cells lacking the mirn23a miRNA cluster have decreased inflammatory signaling (TLR, Type I and II IFNs, TNF and IL-6). Since these pathways are critical for the function of macrophages, we investigated mirn23a regulation of macrophage inflammatory responses and polarization. Previous work investigating the role of individual mirn23a miRNAs (miRs-23a, −24–2, and −27a) in regulating the inflammatory/polarization state of macrophages used overexpression and under expression techniques yielding contradictory results(20–24). To clarify the role of mirn23a miRNAs in regulating macrophage function we examined BMDMs prepared from wildtype and mirn23a knockout mice. Consistent with the RNA-seq analysis of myeloid progenitor we observed that LPS treatment of wildtype and mirn23a−/− BMDMs resulted in decreased upregulation of inflammatory cytokines Il1b, Tnf, Il6 and Il12b. In addition, we observed upregulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine Il10. Similarly, when we polarized macrophages under M1 (IFNγ and LPS) and M2 (IL-4, IL-13) conditions we observed decreased expression of M1 associated genes and increased expression of M2 genes respectively by mutant cells. When we overexpress the mirn23a cluster in RAW264.7 macrophages, cluster overexpression increased expression of M1 associated genes (Tnf and Nos2) and decreased expression of M2 genes (Arg1 and Il10) when polarized under M1 and M2 conditions respectively. The data suggest that mirn23a miRNAs act as repressors of M2 polarization and augment inflammatory signaling required for M1 polarization.

Interestingly endogenous expression of mirn23a miRNAs is repressed with LPS treatment (Fig 2A, 3A). Similarly shifting BMDM from M-CSF media which primes M2 polarization to GM-CSF containing media which primes M1 polarization results in a ~2-fold decrease in miRs-23a, −24, and −27a (Fig S1E). In addition, mirn23a miRNAs are increased with stimulation by the M2 polarizing cytokine IL-4(27). Unlike polarized T helper cells, macrophages are not committed to a specific polarization(65). They remain “plastic” and can be repolarized. This is biologically seen with tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) which can enter a tumor as M1 polarized macrophages but respond to tumor secreted factors by repolarizing to an M2 phenotype. Our data suggests that the mirn23a miRNAs are involved in maintaining the plasticity of polarized macrophages. We propose that in M2 polarized macrophages mirn23a miRNAs are induced to buffer the expression of M2 genes to maintain protein levels within a specific window of expression. Preventing the cell from obtaining high levels of these M2 factors contributes to the ability of the M2 cells to be repolarized to an M1 phenotype. In the absence of mirn23a, M2 cells are more prone to being “locked-in” to the M2 phenotype. Conversely in M1 polarized cells mirn23a is repressed which makes it easier for M1 cells to re-express M2 associated genes and allow for repolarization to M2. This may explain why we observed greater changes in gene expression in mutant M1 macrophages compared to M2 in the RNA-seq analysis. We derived our macrophages culturing bone marrow in the presence of M-CSF which can skew polarization of macrophages to M2 in part due to increased activation of FoxO1(66). We propose that normally mirn23a miRNAs are induced so that M2 cells are able to repolarize to M1. In the absence of mirn23a it is more difficult to repolarize mirn23a−/− M2 skewed cells to M1 and thus we observe an increased in the number of differentially expressed cells between wildtype and mutant macrophages treated with IFNγ and LPS.

LPS induced downregulation of mirn23a is mediated by transcriptional repression induced by NF-κB protein p65(35). LPS signaling through TLR4 is a well-recognized mechanism of NF-κB activation leading to expression of inflammatory genes. Unrestrained inflammatory activity can lead to tissue damage and autoimmunity so to downregulate NF-κB induces a negative feedback loop through transcribing its inhibitors Nfkbia (Iκbα) and Tnfaip3(A20). Mice lacking Tnfaip3 die from an hyperinflammatory response(67). MiR-23a directly target Tnfaip3 transcripts to reduce expression of A20 protein, which supports the conclusion that LPS/ p65 repression of mirn23a is part of the NF-κB feedback mechanism to limit the inflammatory response(39, 47). Our data support that mirn23a physiologically regulates NF-κB signaling as we observed decreases in Il-1b, Il-12b, Tnf, and Nos2, well known genes regulated by NF-κB. A20 protein levels are higher in mirn23a−/− BMDMs, which likely contributes to the downregulation of these inflammatory genes in mutant macrophages (Fig 3D).

The effects on in vitro macrophage responses to LPS and polarization were significant but fairly modest. However in vitro stimulation of cells is likely stronger than the signals observed in vivo so it was important to examine if loss of mirn23a had repercussions in vivo where we could observe cell responses to physiological stimuli. To demonstrate the in vivo significance of the mirn23a mediated macrophage polarization effects we have observed in vitro, we generated syngeneic tumors in wildtype and mutant mice. M2 polarization of macrophages by tumor cells contributes to the growth of ovarian tumor ID8 cells and LLC cells in vivo(54, 55, 64). Inhibiting macrophage M2 polarization results in decreased growth of ID8 and LLC tumors in vivo. We hypothesized that since the absence of mirn23a skewed macrophages toward M2 polarization in vitro that tumors would grow faster in mutant mice compared to wildtype. Consistent with our hypothesis mirn23a mice succumbed to i.p. ID8 tumors sooner than wildtype mice, and they had increased LLC tumor growth when monitored over time. LLC tumors generated in mutant mice had increased infiltration of F4/80+CD206+ macrophages. Although macrophages are critical in mediating the immune response to ID8 and LLC derived tumors it is possible that the decreased survival was due to loss of expression in other immune cell types. Mirn23a deficient T helper cells skew towards Th2 polarization and mirn23a miRNAs regulate T regulatory (Treg) cell function. Additionally, our group has published that mirn23a−/− NK cells have reduced production of inflammatory cytokines and have reduced anti-tumor activity (68). We examined mirn23a−/− macrophage contribution to increased LLC tumor growth in mutant animals by co-injecting wildtype mice with LLC cells and either wildtype or mirn23a−/− BMDMs. This experiment demonstrated that mirn23a deficiency in macrophages alone could potentiate tumor growth, though it does not rule out contribution in other immune cells.

Leveraging miRNAs as a therapeutic option in inflammatory disease is attractive in part because miRNAs “fine-tune” gene expression. Targeting miRNAs may be an easier way to modulate inflammation as opposed to other pharmaceutical methods that may ablate the inflammatory response. Having this control could be useful in complex inflammatory diseases such as cancer. Tumors manipulate local immune cells such as macrophages to suppress immune responses and evade the immune system(69). These same cells maintain a low level of inflammatory cytokines that continue to promote tumor development. However, when these immune cells maintain a more inflammatory phenotype, the immune response combats the tumor. However, too much inflammation can produce systemic responses that may be harmful to the host. Therefore, precise localized regulation of inflammation in the tumor microenvironment has clinical benefits. Our data suggest that mirn23a expression in the tumor microenvironment regulates survival in response to tumors, setting a proof of principle that mirn23a can be manipulated to influence disease progression. Recently, it was demonstrated that delivery of miR-182 to glioblastoma cells enhances tumor susceptibility to chemotherapy(70). Additionally, lentiviral co-expression of multiple miRNAs (MiRs-124, −128, and −137) in a glioblastoma cell line synergized to increase survival in transplanted mice as well as increase susceptibility to chemotherapy in mouse models(71). Potentially using cocktails of miRNAs mimics and antagonist targeted to macrophages will allow for specific polarization and/or repolarization of macrophages. Several studies demonstrate successful delivery of miRNAs to macrophages in vivo using functionalized nanoparticles in mouse models(72–74). By deciphering the extent to which different miRNAs regulate inflammatory pathways, and which pathways they specifically regulate, miRNA combinatorial therapies can be designed for a variety of inflammatory diseases and be utilized for personalized therapy.

Supplementary Material

Keypoints:

Mirn23a miRNAs repress inflammatory signaling in myeloid progenitors.

Mirn23a−/− macrophages have enhanced M2 polarization and decreased responses to LPS.

Mirn23a−/− macrophages enhance the growth of syngeneic tumors in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of the University of Notre Dame Freimann Life Sciences Center for mouse breeding and husbandry. We would like Melissa Stephens, Joseph Soros and the staff of the University of Notre Dame Genomics and Bioinformatic Core Facility for preparation of sequencing libraries and data analysis. This work was supported by the Indiana University School of Medicine—South Bend Imaging and Flow Cytometry Core Facility. Lastly, we would like to thank former colleagues Drs. Suzanne S. Bohlson (University of California, Irvine) and Manuel D. Galvan (National Jewish Health) for helpful discussions at the beginning of this project.

Funding: This work was supported by the NIDDK DK109051 (RD), Ralph W. and Grace M. Showalter Research Trust Fund (RD), Indiana CTSI (RD), NCI CA204231 (SR), Walther Cancer Foundation Inter-disciplinary Interface Training Program (AB) and Research Like a Champion University of Notre Dame (AB).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Franken L, Schiwon M, and Kurts C. 2016. Macrophages: sentinels and regulators of the immune system. Cell Microbiol 18: 475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theret M, Mounier R, and Rossi F. 2019. The origins and non-canonical functions of macrophages in development and regeneration. Development 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watanabe S, Alexander M, Misharin AV, and Budinger GRS. 2019. The role of macrophages in the resolution of inflammation. J Clin Invest 129: 2619–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponzoni M, Pastorino F, Di Paolo D, Perri P, and Brignole C. 2018. Targeting Macrophages as a Potential Therapeutic Intervention: Impact on Inflammatory Diseases and Cancer. International journal of molecular sciences 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atri C, Guerfali FZ, and Laouini D. 2018. Role of Human Macrophage Polarization in Inflammation during Infectious Diseases. International journal of molecular sciences 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu YC, Zou XB, Chai YF, and Yao YM. 2014. Macrophage polarization in inflammatory diseases. International journal of biological sciences 10: 520–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Platanitis E, and Decker T. 2018. Regulatory Networks Involving STATs, IRFs, and NFkappaB in Inflammation. Frontiers in immunology 9: 2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Groot AE, and Pienta KJ. 2018. Epigenetic control of macrophage polarization: implications for targeting tumor-associated macrophages. Oncotarget 9: 20908–20927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruidenier L, Chung CW, Cheng Z, Liddle J, Che K, Joberty G, Bantscheff M, Bountra C, Bridges A, Diallo H, Eberhard D, Hutchinson S, Jones E, Katso R, Leveridge M, Mander PK, Mosley J, Ramirez-Molina C, Rowland P, Schofield CJ, Sheppard RJ, Smith JE, Swales C, Tanner R, Thomas P, Tumber A, Drewes G, Oppermann U, Patel DJ, Lee K, and Wilson DM. 2012. A selective jumonji H3K27 demethylase inhibitor modulates the proinflammatory macrophage response. Nature 488: 404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Essandoh K, Li Y, Huo J, and Fan GC. 2016. MiRNA-Mediated Macrophage Polarization and its Potential Role in the Regulation of Inflammatory Response. Shock 46: 122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartel DP 2004. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Zhang M, Zhong M, Suo Q, and Lv K. 2013. Expression profiles of miRNAs in polarized macrophages. Int J Mol Med 31: 797–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Zhang J, Guo H, Yang S, Fan W, Ye N, Tian Z, Yu T, Ai G, Shen Z, He H, Yan P, Lin H, Luo X, Li H, and Wu Y. 2018. Critical Role of Alternative M2 Skewing in miR-155 Deletion-Mediated Protection of Colitis. Frontiers in immunology 9: 904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Mei H, Chang X, Chen F, Zhu Y, and Han X. 2016. Adipocyte-derived microvesicles from obese mice induce M1 macrophage phenotype through secreted miR-155. Journal of molecular cell biology 8: 505–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boldin MP, Taganov KD, Rao DS, Yang L, Zhao JL, Kalwani M, Garcia-Flores Y, Luong M, Devrekanli A, Xu J, Sun G, Tay J, Linsley PS, and Baltimore D. 2011. miR-146a is a significant brake on autoimmunity, myeloproliferation, and cancer in mice. J Exp Med 208: 1189–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li D, Duan M, Feng Y, Geng L, Li X, and Zhang W. 2016. MiR-146a modulates macrophage polarization in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis by targeting INHBA. Mol Immunol 77: 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong KY, Owens KS, Rogers JH, Mullenix J, Velu CS, Grimes HL, and Dahl R. 2010. MIR-23A microRNA cluster inhibits B-cell development. Exp Hematol 38: 629–640 e621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurkewich JL, Bikorimana E, Nguyen T, Klopfenstein N, Zhang H, Hallas WM, Stayback G, McDowell MA, and Dahl R. 2016. The mirn23a microRNA cluster antagonizes B cell development. J Leukoc Biol 100: 665–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurkewich JL, Hansen J, Klopfenstein N, Zhang H, Wood C, Boucher A, Hickman J, Muench DE, Grimes HL, and Dahl R. 2017. The miR-23a~27a~24–2 microRNA cluster buffers transcription and signaling pathways during hematopoiesis. PLoS Genet 13: e1006887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie N, Cui H, Banerjee S, Tan Z, Salomao R, Fu M, Abraham E, Thannickal VJ, and Liu G. 2014. miR-27a regulates inflammatory response of macrophages by targeting IL-10. J Immunol 193: 327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussain T, Zhao D, Shah SZA, Wang J, Yue R, Liao Y, Sabir N, Yang L, and Zhou X. 2017. MicroRNA 27a-3p Regulates Antimicrobial Responses of Murine Macrophages Infected by Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis by Targeting Interleukin-10 and TGF-beta-Activated Protein Kinase 1 Binding Protein 2. Frontiers in immunology 8: 1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Q, Hou J, Zhou Y, Yang Y, and Cao X. 2016. Type I IFN-Inducible Downregulation of MicroRNA-27a Feedback Inhibits Antiviral Innate Response by Upregulating Siglec1/TRIM27. J Immunol 196: 1317–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saha B, Momen-Heravi F, Kodys K, and Szabo G. 2016. MicroRNA Cargo of Extracellular Vesicles from Alcohol-exposed Monocytes Signals Naive Monocytes to Differentiate into M2 Macrophages. J Biol Chem 291: 149–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saha B, Bruneau JC, Kodys K, and Szabo G. 2015. Alcohol-induced miR-27a regulates differentiation and M2 macrophage polarization of normal human monocytes. J Immunol 194: 3079–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jingjing Z, Nan Z, Wei W, Qinghe G, Weijuan W, Peng W, and Xiangpeng W. 2017. MicroRNA-24 Modulates Staphylococcus aureus-Induced Macrophage Polarization by Suppressing CHI3L1. Inflammation 40: 995–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naqvi AR, Fordham JB, Ganesh B, and Nares S. 2016. miR-24, miR-30b and miR-142–3p interfere with antigen processing and presentation by primary macrophages and dendritic cells. Scientific reports 6: 32925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma S, Liu M, Xu Z, Li Y, Guo H, Ge Y, Liu Y, Zheng D, and Shi J. 2015. A double feedback loop mediated by microRNA-23a/27a/24–2 regulates M1 versus M2 macrophage polarization and thus regulates cancer progression. Oncotarget. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Y, Yao N, Liu G, Dong L, Liu Y, Zhang M, Wang F, Wang B, Wei X, Dong H, Wang L, Ji S, Zhang J, Wang Y, Huang Y, and Yu J. 2015. Functional screen reveals essential roles of miR-27a/24 in differentiation of embryonic stem cells. EMBO J 34: 361–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Si X, Cao D, Chen J, Nie Y, Jiang Z, Chen MY, Wu JF, and Guan XD. 2018. miR23a downregulation modulates the inflammatory response by targeting ATG12mediated autophagy. Molecular medicine reports 18: 1524–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walton J, Blagih J, Ennis D, Leung E, Dowson S, Farquharson M, Tookman LA, Orange C, Athineos D, Mason S, Stevenson D, Blyth K, Strathdee D, Balkwill FR, Vousden K, Lockley M, and McNeish IA. 2016. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Trp53 and Brca2 Knockout to Generate Improved Murine Models of Ovarian High-Grade Serous Carcinoma. Cancer Res 76: 6118–6129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, and Mesirov JP. 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fabregat A, Jupe S, Matthews L, Sidiropoulos K, Gillespie M, Garapati P, Haw R, Jassal B, Korninger F, May B, Milacic M, Roca CD, Rothfels K, Sevilla C, Shamovsky V, Shorser S, Varusai T, Viteri G, Weiser J, Wu G, Stein L, Hermjakob H, and D’Eustachio P. 2018. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res 46: D649–D655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kramer A, Green J, Pollard J Jr., and Tugendreich S. 2014. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 30: 523–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arthur JS, and Ley SC. 2013. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 679–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rathore MG, Saumet A, Rossi JF, de Bettignies C, Tempe D, Lecellier CH, and Villalba M. 2012. The NF-kappaB member p65 controls glutamine metabolism through miR-23a. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44: 1448–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amano F, and Akamatsu Y. 1991. A lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-resistant mutant isolated from a macrophagelike cell line, J774.1, exhibits an altered activated-macrophage phenotype in response to LPS. Infect Immun 59: 2166–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams LM, and Ridley AJ. 2000. Lipopolysaccharide induces actin reorganization and tyrosine phosphorylation of Pyk2 and paxillin in monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol 164: 2028–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boone DL, Turer EE, Lee EG, Ahmad RC, Wheeler MT, Tsui C, Hurley P, Chien M, Chai S, Hitotsumatsu O, McNally E, Pickart C, and Ma A. 2004. The ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20 is required for termination of Toll-like receptor responses. Nat Immunol 5: 1052–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng P, Li Z, and Liu X. 2015. Reduced Expression of miR-23a Suppresses A20 in TLR-stimulated Macrophages. Inflammation 38: 1787–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma X, Yan W, Zheng H, Du Q, Zhang L, Ban Y, Li N, and Wei F. 2015. Regulation of IL-10 and IL-12 production and function in macrophages and dendritic cells. F1000Res 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas AC, and Mattila JT. 2014. “Of mice and men”: arginine metabolism in macrophages. Frontiers in immunology 5: 479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agoro R, Taleb M, Quesniaux VFJ, and Mura C. 2018. Cell iron status influences macrophage polarization. PLoS One 13: e0196921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jablonski KA, Amici SA, Webb LM, Ruiz-Rosado Jde D, Popovich PG, Partida-Sanchez S, and Guerau-de-Arellano M. 2015. Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PLoS One 10: e0145342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ying W, Cheruku PS, Bazer FW, Safe SH, and Zhou B. 2013. Investigation of macrophage polarization using bone marrow derived macrophages. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alleva DG, Johnson EB, Lio FM, Boehme SA, Conlon PJ, and Crowe PD. 2002. Regulation of murine macrophage proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines by ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma: counter-regulatory activity by IFN-gamma. J Leukoc Biol 71: 677–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen CH, and Stavnezer J. 1998. Interaction of stat6 and NF-kappaB: direct association and synergistic activation of interleukin-4-induced transcription. Mol Cell Biol 18: 3395–3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma Y, Wang B, Jiang F, Wang D, Liu H, Yan Y, Dong H, Wang F, Gong B, Zhu Y, Dong L, Yin H, Zhang Z, Zhao H, Wu Z, Zhang J, Zhou J, and Yu J. 2013. A feedback loop consisting of microRNA-23a/27a and the beta-like globin suppressors KLF3 and SP1 regulates globin gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wimmer N, Huber B, Barabas N, Rohrl J, Pfeffer K, and Hehlgans T. 2012. Lymphotoxin beta receptor activation on macrophages induces cross-tolerance to TLR4 and TLR9 ligands. J Immunol 188: 3426–3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li L, Ng DS, Mah WC, Almeida FF, Rahmat SA, Rao VK, Leow SC, Laudisi F, Peh MT, Goh AM, Lim JS, Wright GD, Mortellaro A, Taneja R, Ginhoux F, Lee CG, Moore PK, and Lane DP. 2015. A unique role for p53 in the regulation of M2 macrophage polarization. Cell Death Differ 22: 1081–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma WT, Gao F, Gu K, and Chen DK. 2019. The Role of Monocytes and Macrophages in Autoimmune Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in immunology 10: 1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pathria P, Louis TL, and Varner JA. 2019. Targeting Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Cancer. Trends Immunol 40: 310–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F, Seifi B, Mohammadi A, Afshari JT, and Sahebkar A. 2018. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol 233: 6425–6440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goswami KK, Ghosh T, Ghosh S, Sarkar M, Bose A, and Baral R. 2017. Tumor promoting role of anti-tumor macrophages in tumor microenvironment. Cell Immunol 316: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hagemann T, Wilson J, Burke F, Kulbe H, Li NF, Pluddemann A, Charles K, Gordon S, and Balkwill FR. 2006. Ovarian cancer cells polarize macrophages toward a tumor-associated phenotype. J Immunol 176: 5023–5032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hagemann T, Lawrence T, McNeish I, Charles KA, Kulbe H, Thompson RG, Robinson SC, and Balkwill FR. 2008. “Re-educating” tumor-associated macrophages by targeting NF-kappaB. J Exp Med 205: 1261–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baig MS, Roy A, Rajpoot S, Liu D, Savai R, Banerjee S, Kawada M, Faisal SM, Saluja R, Saqib U, Ohishi T, and Wary KK. 2020. Tumor-derived exosomes in the regulation of macrophage polarization. Inflamm Res 69: 435–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Komohara Y, Ohnishi K, Kuratsu J, and Takeya M. 2008. Possible involvement of the M2 anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype in growth of human gliomas. J Pathol 216: 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pritchard A, Tousif S, Wang Y, Hough K, Khan S, Strenkowski J, Chacko BK, Darley-Usmar VM, and Deshane JS. 2020. Lung Tumor Cell-Derived Exosomes Promote M2 Macrophage Polarization. Cells 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Y, Qin J, Lan L, Li N, Wang C, He P, Liu F, Ni H, and Wang Y. 2014. M-CSF cooperating with NFkappaB induces macrophage transformation from M1 to M2 by upregulating c-Jun. Cancer Biol Ther 15: 99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]