Abstract

Purpose

NRG Oncology, part of the National Cancer Institute’s National Clinical Trials Network, took efforts to increase patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) completion and institutional data submission rates within clinical trials. Lack of completion diminishes power to draw conclusions and can be a waste of resources. It is hypothesized that trials with automatic email reminders and past due notifications will have PROM forms submitted more timely with higher patient completion.

Methods

Automatic emails sent to the research associate were added to selected NRG Oncology trials. Comparisons between trials with and without automatic emails were analyzed using Chi-square tests with respect to patient completion and timeliness of form submission rates. Multivariable analyses were conducted using repeated measures generalized estimating equations. If PROMs were not completed, a form providing the reason why was submitted and counted towards form submission.

Results

For both disease sites, form submission was significantly higher within one month of the form’s due date for the studies with automatic emails vs. those without (prostate: 79.7% vs. 75.7%, p<0.001; breast: 59.2% vs. 31.3%, p<0.001). No significant differences in patient completion were observed between the breast trials. The prostate trial with automatic emails had significantly higher patient completion but this result was not confirmed in the multivariable analysis.

Conclusions

Although patient completion rates were higher on trials with automatic emails, there may be confounding factors requiring future study. The automatic emails appeared to have increased the timeliness of form submission, thus supporting their continued use on NRG Oncology trials.

Keywords: Quality of life, neurocognitive testing, patient-reported outcomes, patient compliance, delinquent data, form submission

Introduction

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), assessments completed by a patient regarding their physical, functional, and psychological status, are a crucial component of oncology research and can lead to improved care and patient-physician communication [1–3]. Like other types of data collected on a clinical trial, such as laboratory values and disease assessment, PROMs are susceptible to missing data due to institutional error and delinquent or missing form submission. However, unlike these other types of data, PROMs are likely to have a higher rate of missing data due to patient non-compliance in completing the assessment [4]. There are several reasons for non-completion including patient refusal, the institution is unable to contact the patient, the patient withdrew consent from the trial, the form was completed too early or too late from the scheduled time point, and an form was submitted incomplete (i.e. not enough questions were answered in order to properly score the assessment) [5–10]. Studies have shown that non-compliant patients may differ from compliant patients in terms of various factors such as age, performance status, and disease [4, 11–14] Consequently, missing data can negatively impact the analysis, requiring various missing data techniques and sensitivity analyses to be employed [15, 16]. Patient completion at the protocol-specified time point is necessary for analysis while submission of the form by the research associate (RA) (in the case of paper forms) shortly after patient completion allows for accurate monitoring of PROM completion.

NRG Oncology, part of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) National Clinical Trials Network, conducted a double-blinded placebo-controlled phase III trial of memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole brain radiotherapy, identified as NRG-RTOG 0614 [17]. The primary endpoint was a neurocognitive assessment at 24 weeks. Although the primary endpoint tool is not considered a PROM, it is a tool that requires the patient to interact with a test administrator to complete the assessment and is thus plagued by the same difficulties as PROMs. The trial was designed such that 442 patients would provide 80% statistical power to detect a meaningful difference between the arms at 24 weeks, however only 141 patients completed the assessment at 24 weeks. Eleven percent of patients withdrew consent, 34% died, and 26% did not complete the 24-week assessment due to various patient and institutional related reasons. As a result, the trial only had 35% statistical power to detect the hypothesized difference between arms. In this scenario, the trial findings were not statistically significant but it is uncertain if the findings are due to lack of power to detect differences or null findings attributable to the large amount of missing data.

This trial triggered a movement in NRG Oncology to reduce both PROM non-completion and institutional data forms delinquency. Basch published several methods to increase patient completion of PROMs, which includes keeping staff at participating institutions engaged, collecting the reasons PROMs were not completed, and monitoring compliance in real-time [18]. In line with these suggested methods, NRG Oncology implemented a pilot program of automatic emails consisting of reminder emails and past due notifications to RAs on select NRG Oncology trials. Thus, the aim of this analysis is to evaluate the effectiveness of these email reminders and past due notifications on PROM form submission timeliness and patient completion rates.

Methods

Study Design

In order to evaluate the ability of the automatic email reminders and past due notifications to improve timeliness of form submission rates and patient compliance, trials with automatic emails were matched to trials without automatic emails. One breast and one prostate cancer trial were selected due to availability of a match with respect to patient population and PROMs collected.

All four protocols clearly stated the time points PROMs were to be completed with no other means of reminding RAs of upcoming or past due PROMs outside of the automatic emails on two of four the trials. Details on the four trials can be found in Supplemental Table 1. Briefly, NRG-RTOG 1005 is phase III trial for stage 0, I, and II breast cancer patients that had automatic emails for the patient-reported cosmesis evaluation as part of the PRO substudy requiring a separate consent. This cosmesis form asked the patient about the cosmetic result of the treated breast compared to the untreated breast and the patient’s satisfaction with their treatment and results [19]. NRG-RTOG 0319 is a phase I/II trial of patients with stage I and II breast carcinoma in which only phase II collected PROs. This trial enrolled patients prior to implementation of the automatic emails and also collected the patient-reported cosmesis evaluation.

Automatic emails were implemented for the PRO substudy of NRG-RTOG 0924, a phase III trial of unfavorable intermediate or favorable high-risk prostate cancer. NRG-RTOG 0815, a phase III trial of intermediate risk prostate cancer, did not have automatic emails as part of its PRO substudy. Both trials required consent to participant in the PRO substudy, had similar patient populations, and were open to accrual at the same time making these trials ideal to compare PRO form submission and compliance rates. There are 4 PROMs of interest that were identical between these two prostate studies. A single item from the PSQI, a self-rated questionnaire that measures sleep quality and disturbances, was used to measure sleep quality [20]. Patient’s level of physical activity was assessed using the 4-item GLTEQ, which measures time spent per week in each of light, moderate, and vigorous activities [21, 22]. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) were combined onto a single form for completion by the patient. The PROMIS-Fatigue short form consists of 7 items with consistent responses, broad coverage across the fatigue spectrum and good precision of measurement [23]. The EuroQol’s EQ-5D is a patient self-administrated questionnaire consisting of 2 parts [24]. The first has 5 items covering 5 dimensions including: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The second part is a visual analog scale assessing overall quality of life.

To further understand the issues behind patient non-compliance of PROMs, a targeted survey of sites from NRG Oncology trials with either a low patient compliance rate or low rates of patients consenting to PRO components to NRG Oncology clinical trials was conducted. RAs, specifically those designated as “Lead” or “Co-lead” by their institution, were targeted for survey participation. Institutions were selected if more than two patients were enrolled and either the patient compliance rate and/or consent rate to the PRO components was in the bottom 50% of all enrolling institutions. Emails, including reminder emails, were sent to 184 RAs from 101 institutions with a link to Survey Monkey for completion. The survey was anonymous in order to elicit more responses.

Intervention

For the breast and prostate cancer trials with automatic emails, reminder emails were sent to the institutional RA monitoring the patient 15 days prior to the due date and on the due date of each post-baseline PROM. Baseline forms were not included since they are typically completed by the patient after signing consent but before trial registration. These emails serve as a reminder to the RA to prepare for an upcoming visit by notifying them of the PROMs that are due. Past due notifications are sent to the same institutional RA at 30, 60, and 90 days past the due date and serve two purposes: 1) as a reminder to submit the relevant data, and 2) to continue to try to obtain the PROM from the patient within the allowable time window. Once the PROM data or a form stating the reason why the PROM was not completed have been submitted, the emails are suppressed.

Statistical Considerations

Patient completion was categorized into complete vs. not complete with a completed assessment defined as a minimum number of questions answered to calculate a score and was completed within the corresponding timeframe. Form submission and timeliness of submission, both within disease site and by disease site, were assessed by comparing either the date of PROM completion by the patient or date that the RA provided the reason for non-compliance to the PROM due date. This was then categorized as being submitted within 1 month of the due date, 1–3 months of the due date, and more than 3 months past the due date/not submitted. Baseline PROMs were excluded from all analyses since no automatic emails are sent for this time point.

The analysis included all eligible patients who consented to the PRO component of the 4 trials. Subset analyses examining patients enrolled by institutions that participated in the comparative trials was also conducted. For example, only institutions that enrolled eligible patients consenting to the PRO component on both breast cancer trials would be considered for the subset analysis. Chi-square tests, and Fisher’s exact test if necessary, were used to compare PROM completion and form submission rates between trials with and without automatic emails. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from repeated measures generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to assess PROM completion while adjusting for trial and patient characteristics. These models were not performed using form submission rates since these rates are most likely not affected by trial or patient characteristics. For prostate cancer trials, adjustment was made for timepoint of assessment, age (≤65 years vs. > 65 years), Zubrod (0 vs. 1), race (white vs. non-white), baseline PSA (<10 vs. 10–20 vs. >20), and T-stage (T1 vs. T2).

For breast cancer trials, adjustment was made for timepoint of assessment, age (≤60 years vs. > 60 years), race (white vs. non-white), and stage (0/I vs. II). The analysis of the RA survey results was descriptive, only including counts and proportions of each response. A two-sided type I error of 0.05 was used to assess significance in this retrospective analysis.

Results

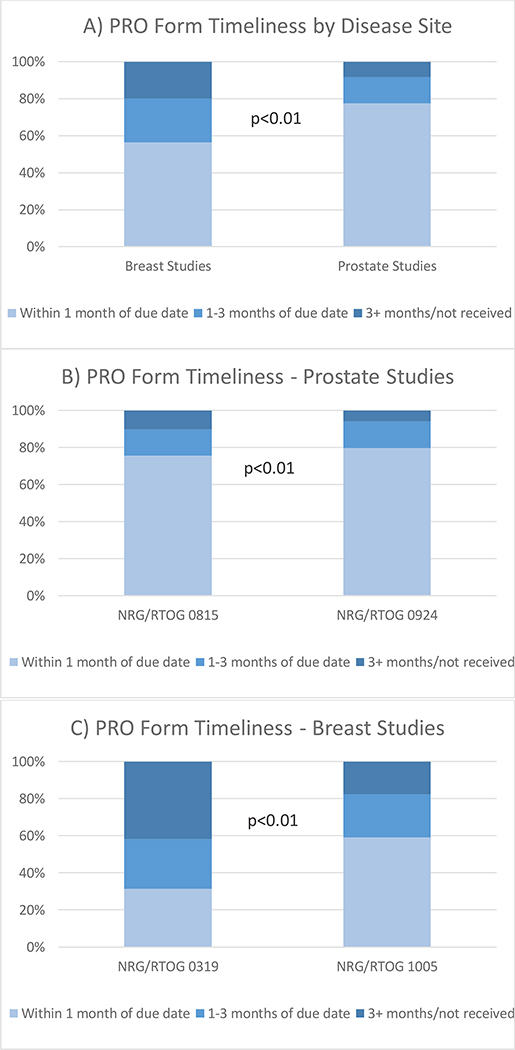

The PROMs for prostate trials were submitted in a significantly more timely window per protocol than for breast trials (77.6% submitted within 1 month vs. 56.5%, p<0.001; Figure 1a). In fact, there are no outstanding forms for the prostate trials, noting that this includes all forms that were completed by the patient or the form stating the reason why the PROM was not completed was submitted. For both the breast and prostate trials, the PROMs submission was significantly more timely for the trials with automatic emails as compared to those without (prostate: 79.7% within one month for the trial with automatic emails vs. 75.7% for the trial without, p<0.001, Figure 1b; and breast: 59.2% within one month for the trial with automatic emails vs. 31.3% for the trial without, p<0.001, Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

PRO Form Timeliness. PRO=Patient-reported outcome

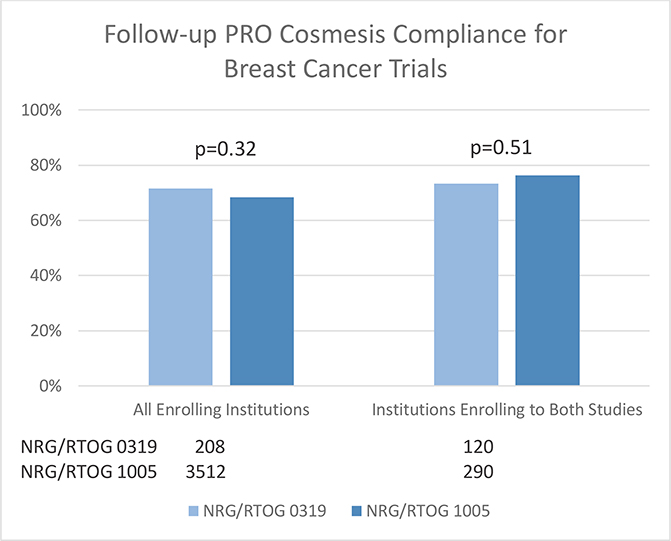

When comparing the breast cancer trials, for patients from all enrolling institutions and limiting to institutions who enrolled patients on both trials, no significant differences were observed, although the compliance rates were higher for the trial with automatic emails (Figure 2). Multivariable analysis did not show a significant association between studies (Table 1a), rather only a significant difference between the 36 month and 6 month PROM completion rates (OR=0.41, 95% CI: 0.24, 0.71, p=0.0014; Table 1d).

Figure 2.

Follow-Up PRO Cosmesis Compliance for Breast Studies. PRO=Patient-reported outcome; Time windows used to determine compliance for completed forms: 6 months +/− 6 weeks; 1 year +/− 8 weeks; 5 years +/− 12 weeks.

Table 1.

PRO Compliance Multivariate Analysis Institutions that Enrolled to Both Studies

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence | Interval p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A) Prostate - EQ-5D | |||

| Intercept | 17.44 | −1.32,1.07 | 0.83 |

| Time=1 Year (6 months) | 0.34 | −1.40,−0.78 | <0.001 |

| Time=5 Years (6 months) | 0.41 | −1.18,−0.60 | <0.001 |

| Age (≤ 65) | 0.69 | −0.68,−0.06 | 0.020 |

| Zubrod (0) | 1.56 | −0.01,0.89 | 0.053 |

| Race (White) | 1.30 | −0.08,0.60 | 0.13 |

| Baseline PSA = 10–20 ( < 10) | 0.94 | −0.63,0.51 | 0.84 |

| Baseline PSA = > 20 ( <10) | 1.40 | −0.25,0.93 | 0.26 |

| T-Stage (T1) | 1.13 | −0.19,0.44 | 0.44 |

| Study (NRG/RTOG 0815) | 0.630 | 0.45, 0.88 | 0.006 |

| B) Prostate - PROMIS | |||

| Intercept | 1.59 | 0.49, 5.18 | 0.44 |

| Time=1 Year (6 months) | 4.09 | 2.93, 5.705 | <0.001 |

| Time=5 Years (6 months) | 3.09 | 2.30, 4.15 | <0.001 |

| Age (≤ 65) | 1.44 | 1.05, 1.98 | 0.024 |

| Zubrod (0) | 0.62 | 0.38, 0.99 | 0.048 |

| Race (White) | 0.76 | 0.54, 1.07 | 0.12 |

| Baseline PSA = 10–20 ( < 10) | 0.96 | 0.54, 1.69 | 0.88 |

| Baseline PSA = > 20 ( <10) | 0.76 | 0.42, 1.40 | 0.38 |

| T-Stage (T1) | 0.90 | 0.65, 1.23 | 0.50 |

| Study (NRG/RTOG 0815) | 1.33 | 0.94, 1.86 | 0.10 |

| C) Prostate – PSQI/GLTEQ | |||

| Intercept | 1.84 | 0.59, 5.72 | 0.30 |

| Time=1 Year (6 months) | 3.84 | 2.73, 5.38 | <0.001 |

| Time=5 Years (6 months) | 2.55 | 190, 3.43 | <0.001 |

| Age (≤ 65) | 1.45 | 1.07, 1.98 | 0.018 |

| Zubrod (0) | 0.72 | 0.43, 1.19 | 0.20 |

| Race (White) | 0.73 | 0.52, 1.01 | 0.057 |

| Baseline PSA = 10–20 ( < 10) | 0.93 | 0.52, 1.64 | 0.80 |

| Baseline PSA = > 20 ( <10) | 0.78 | 0.43, 1.43 | 0.42 |

| T-Stage (T1) | 0.86 | 0.63, 1.18 | 0.36 |

| Study (NRG/RTOG 0815) | 1.32 | 0.94, 1.84 | 0.11 |

| D) Cosmesis | |||

| Intercept | 5.52 | 2.95, 10.33 | <0.001 |

| Time=12 months (6 months) | 1.00 | 0.60, 1.69 | 0.99 |

| Time=24 months (6 months) | 0.65 | 0.35, 1.21 | 0.17 |

| Time=36 months (6 months) | 0.41 | 0.24, 0.71 | 0.0014 |

| Age (≤ 60) | 0.67 | 0.36, 1.28 | 0.81 |

| Race (White) | 1.07 | 0.59, 1.96 | 0.62 |

| Stage (0/I) | 1.30 | 0.47, 3.63 | 0.14 |

| Study (RTOG 1005) | 0.63 | 0.34, 1.17 | 0.23 |

Modeling the probability that form completion=Yes (n=1295/1582 for EQ-5D, n=1386/1644for PROMIS, n=1350/1612 for PSQI/GLTEQ, n=378/500 for Cosmesis). Reference Category is specified in brackets (). PRO=Patient-reported outcome; PROMIS=Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PSQI=Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; GLTEQ = Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire.

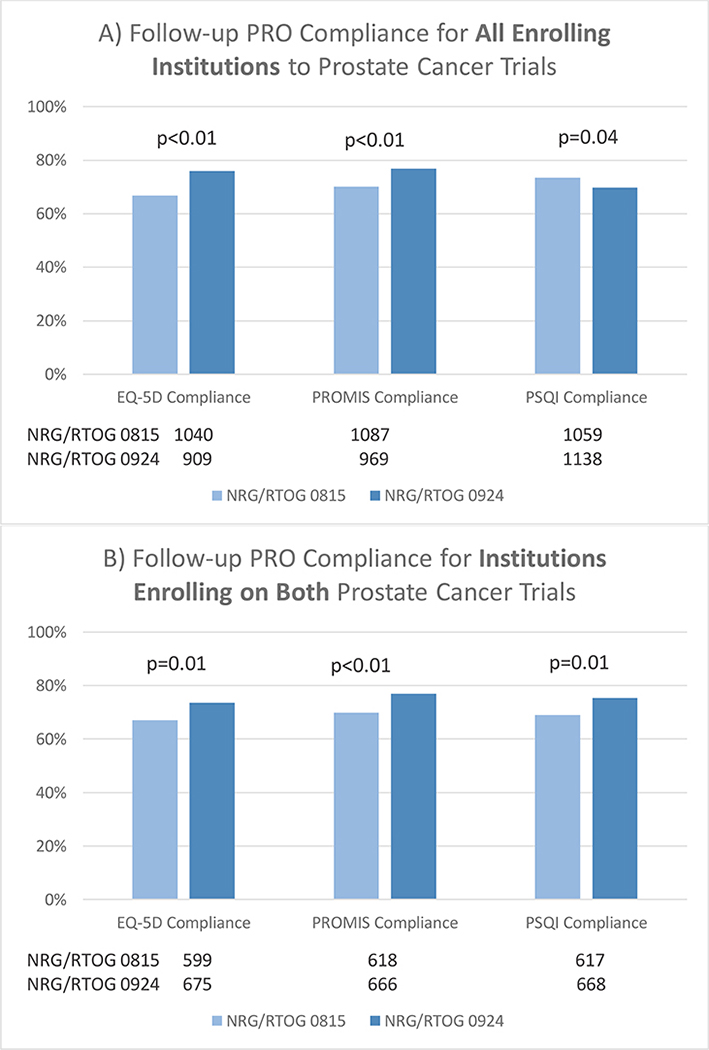

Univariable tests showed significant improvement when considering patients enrolled from all institutions for the prostate cancer trial with automatic emails as compared to the trial without for the EQ-5D (76.0% vs. 66.8%, respectively, p<0.01; Figure 3a) and PROMIS (76.9% vs. 70.2%, respectively, p<0.01). However, the reverse was true for the PSQI/GLTEQ (69.7% vs. 73.5%, respectively, p=0.04). When restricting to institutions that enrolled patients on both trials within a disease site, the prostate trial with automatic emails had significantly higher compliance rates for all 3 PROMs (Figure 3b). Upon multivariable analysis, later time points and older age were associated with lower compliance for all 3 prostate-related PROMs (Table 1b–d). Trial, which serves as a comparison of automatic emails vs. no automatic emails, was only significantly associated with EQ-5D compliance in favor of the prostate trial with automatic emails (OR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.45, 0.88, p<0.01; Table 1b).

Figure 3.

Follow-Up PRO Compliance for Prostate Studies. PRO=Patient-reported outcome; PROMIS=Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PSQI=Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Time windows used to determine compliance for completed forms: 6 months +/− 6 weeks; 1 year +/− 8 weeks; 5 years +/− 12 weeks.

RAs at institutions with low PROM completion rates or PRO component consent rates were targeted for a follow-up survey. The completion rate was 34.8% of all invited RAs and 63.4% of all invited institutions. The two most common burdens experienced by RAs in collection of PRO data are patients missing appointment (60.9%) and that a staff member doesn’t catch the patient at his/her appointment (56.6%; Table 5.1). Only 40.4% of RAs who completed the survey received automatic email reminders with 82.6% of these RAs finding the emails helpful. RAs felt that receiving a single email per case per timepoint (52.2%) and receiving them further in advance would be beneficial (78.3%). Almost all RAs felt that these email reminders and past due notifications would be helpful (90.9%).

Discussion

In this analysis, trials with automatic emails had higher patient compliance and more timely form submission. Although efforts were taken to reduce and adjust for possible confounders by performing subset analysis of sites that enrolled patients on both trials within a disease site as well as multivariable analyses, a number of known and unknown factors could impact PROM completion [25]. The significant improvements seen in the trials with automatic emails were generally not maintained upon multivariable analyses. Land et al [24] implemented similar efforts to increase PROM compliance and submission rates and reported increased compliance compared to older studies however was unable to show that this was due to the implementation of their efforts.

The only PRO form in this analysis for which trial was significantly associated with PROM compliance was the EQ-5D on the prostate trials. The one difference between this form and the other PROMs on the prostate trials is that RAs were required to mail the completed EQ-5D to NRG Oncology Headquarters due to the inclusion of the visual analog scale, which could not be built in the data collection system at the time of trial activation. The other PROMs were data entered by the RA into the electronic data capture system. In line with findings from other studies, age and Zubrod performance status (representing severity of disease) were also associated with patient compliance in prostate trials with older patients and sicker patients having lower PROM completion rates [4, 11]. Also expected and consistent with other studies, time of the PRO assessment had the largest effect on patient compliance with later time points having worse PROM completion for both breast and prostate trials [25, 265]. The rate of patients dropping out of the trial or becoming lost to follow-up only contributes to the decreasing rate of PROM completion. None of the other covariates included in the model were significantly associated with PROM completion on breast trials. Specifically, race did not influence PROM completion; however, some studies found a significant correlation between race and PROM completion [4] while others did not [11–14].Missing data can affect the integrity of an analysis, with the impact varying by the degree and type of missingness [27, 28]. While various statistical methods can be employed to handle missing data, these methods are less reliable than having complete data [27, 28]. After implementing the automatic email reminders in 2011, NRG Oncology has continued to take several steps to reduce missing PRO and neurocognitive testing data with these efforts still ongoing. Electronic PRO (ePRO) data capture is now available on most NRG Oncology trials with PROs giving patients more flexibility on their preferred method of completion in an effort to increase PROM completion [29]. The ePRO tools used by NRG Oncology allow a patient to complete their PROMs outside of the clinic via a tablet or smartphone or using a tablet in the clinic. NRG Oncology established a Missing Data Working Group in 2016 with the goal of identifying sources of patient non-compliance and implementing methods to increase both form submission and PROM completion. The group’s first effort, a PRO delinquency report to monitor form submission and timeliness of submission for every NRG Oncology protocol, was implemented in 2018. Based on these reports, 35 networks (defined as a community or academic main member site with affiliate and satellite sites) with high delinquency rates were contacted and corrective action plans were requested. After 6–8 months, 60% of these 35 networks were no longer delinquent and 14% had reduced rates of delinquency. The working group has interacted with auditors to emphasize PROM and neurocognitive testing completion during audits and raised awareness of compliance issues with NRG by giving presentations to RAs and all of NRG Oncology at the semiannual meetings, including articles in the NRG newsletter, and leading discussions at disease site committee meetings. These efforts occurred after a majority of PRO data was due in the trials included here, and thus had a minimal impact on the analysis.

NRG-CC001 is a follow-up trial to NRG-RTOG 0614 that compared whole brain radiation and memantine to whole brain radiation sparing the hippocampus and memantine [30]. This trial used automatic emails and largely benefited from some of these other initiatives to reduce missing data, which is why it was excluded from the analysis presented here. PROM completion rates can be compared between NRG-CC001 and NRG-RTOG 0614. At 6 months, 17.6% did not complete the assessments within the timeframe, which is less than the rate of 26% observed in NRG-RTOG 0614.

Patient compliance rates can vary by disease site. In the case of NRG-RTOG 0614 and NRG-CC001, the median survival is approximately 7 months, indicating that this is a sick patient population. The breast and prostate cancer studies presented in this paper have a much longer survival, 75–76% alive at 8 years for the prostate cancer patients and 78.8% alive at 7 years for the breast cancer patients [31, 32]. Patients with poor clinical outcomes tend to have lower PROM completion rates and even are more likely to drop out of trials completely, which can bias the results of the study [11, 33]. This analysis could be extended to an assessment of form submission and patient compliance within a sicker patient population, such as brain metastases, while accounting for all methods to increase PROM completion.

Since the adjusted analysis did not clearly show that improvement of PROM completion was due to the automated emails, there are possibly other factors that could impact completion rates. For instance, time period the trial was conducted could be a factor since the trials without automatic emails were activated before the trials with automatic emails. Other efforts include discussions within the relevant committee meetings, such as those for disease site committees, at the NRG Oncology semi-annual meeting, outreach by study chairs, and articles emphasizing the importance of PRO data collection published in NRG newsletters. Thus, it is impossible to tease out the effect of automatic emails.

Improving PROM completion is the ultimate goal, however improving institutional form submission is also needed. Improvement of form submission without an improvement in PROM completion, as was seen in this analysis, means that the form stating the reason why the patient did not complete the PROM are being submitted more frequently but patients are not completing more forms. This is still very helpful information so that future efforts can be targeted to the most common obstacles of PROM completion. Since the RAs generally find the automatic emails to be helpful, albeit with some recommended improvements, the burden of implementing these emails is low. The idea of reminding the RA monitoring the patient of upcoming assessments as well as past due assessments can aid their workflow and help them stay on top of each patient’s calendar, especially in the context of a single RA monitoring several patients. Although these results are specific to the framework of a clinical trial, the notion of setting reminders of upcoming patient visits in which PROMs are collected, for instance, would be beneficial in the clinic setting as well. Thus, these automatic emails should continue to be used as part of a multi-pronged approach to reduce PROM non-completion and increase timeliness of form submission.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Research Associate Survey Responses

| What burdens do you face with respect to collection PRO/QOL data over time? Check all that apply. | (n=64) |

| Patients miss appointments | 39 (60.9%) |

| Patients think the forms are too burdensome | 22 (34.4%) |

| Patients think there are too many PRO forms on a study | 25 (39.1%) |

| Patients think the collection times of PRO forms are too frequent | 17 (26.6%) |

| Staff member doesn’t catch the patient at his/her appointment | 36 (56.6%) |

| Other | 7 (10.9%) |

| Do you or other RAs at your site receive automatic email reminders and past due notifications for PRO/neurocognitive test forms? | (n=57) |

| Yes | 23 (40.4%) |

| No | 34 (59.6%) |

| Do you find these emails helpful? | (n=23) |

| Yes | 19 (82.6%) |

| No | 4 (17.4%) |

| What could be improved with these emails? Check all that apply. | (n=23) |

| Receive a single email rather than 1 per form | 12 (52.2%) |

| Receive them further in advance | 18 (78.3%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) |

| Do you think receiving automatic email reminders and past notifications would be helpful? | (n=33) |

| Yes | 30 (90.9%) |

| No | 3 (9.1%) |

PRO=Patient reported outcomes; QOL = Quality of life; RA=Research associate

Acknowledgments

Funding acknowledgement: This project was supported by grants U10CA180868 (NRG Oncology Operations), U10CA180822 (NRG Oncology SDMC), UG1CA189867 (NCORP), CURE from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Yang LY, Manhas DS, Howard AF, Olson RA. Patient-reported outcome use in oncology: a systematic review of the impact on patient-clinician communication. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(1):41–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stover AM, Tompkins Stricker C, Hammelef K, et al. Using Stakeholder Engagement to Overcome Barriers to Implementing Patient-reported Outcomes (PROs) in Cancer Care Delivery: Approaches From 3 Prospective Studies. Med Care 2019;57 Suppl 5 Suppl 1:S92–S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(8):1305–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atherton PJ, Burger KN, Pederson LD, Kaggal S, Sloan JA. (2016) Patient reported outcomes questionnaire compliance in cancer cooperative group trials (Alliance N0992). Clin Trials, 13(6):612–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, Wefel JS, Blumenthal DT, Vogelbaum MA, Colman H, Chakravarti A, Pugh S, Won M, Jeraj R, Brown PD, Jaeckle KA, Schiff D, Stieber VW, Brachman DG, Werner-Wasik M, Tremont-Lukats IW, Sulman EP, Aldape KD, Curran WJ, Mehta MP. Randomized Clinical Trial of Bevacizumab for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klopp AH, Yeung AR, Deshmukh S, Gil KM, Wenzel L, Westin SN, Gifford K, Gaffney DK, Small W Jr, Thompson S, Doncals DE, Cantuaria GHC, Yaremko BP, Chang A, Kundapur V, Mohan DS, Haas ML, Kim YB, Ferguson CL, Pugh SL, Kachnic KA, Bruner DW. Patient-Reported Toxicity During Pelvic Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy: NRG Oncology-RTOG 1203. JCO. 2018. August 20;36(24):2538–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laack N, Pugh SL, Brown P, Fox S, Wefel J, Meyers C, Choucair A, Khuntia D, Suh J, Roberage D, Kavadi V, Bruner D. Quality of Life in Patients Receiving Memantine for the Prevention of Cognitive Dysfunction During Whole-Brain Radiotherapy (WBRT): a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Neuro-Oncology Practice. 2019;6(4):274–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukka H, Pugh SL, Bruner DW, Bahary JP, Lawton C, Efstathiou J, Kudchadker R, Ponsky LE, Seawrd S, Dayes I, Gopaul D, Michalski J, Delouya G, Kaplan I, Horwitz E, Roach M, Pinover W, Beyer D, Sandler H, Kachnic L. Patient reported outcomes in NRG Oncology RTOG 0938, evaluating two ultrahypofractionated regimens for prostate cancer. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102(2):287–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Movsas B, Hu C, Sloan J, et al. Quality of Life Analysis of a Radiation Dose-Escalation Study of Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0617 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(3):359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wyatt G, Pugh SL, Wong RKW, Sagar SM, Lele SB, Koyfman SA, Nguyen-Tan PF, Yom SS, Cardinale FS, Sultanem K, Hodson DI, Krempl GA, Lukaszczyk B, Yeh AM, Berk L. Xerostomia Health-related Quality of Life: NRG Oncology/RTOG 0537. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(9):2323–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renovanz M, Hechtner M, Kohlmann K, Janko M, Nadji-Ohl M, Singer S, Ringel F, Coburger J, Hickmann A. (2018). Compliance with patient-reported outcome assessment in glioma patients: predictors for drop out. NOP, 5(2):129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bae K, Bruner DW, Baek S, Movsas B, Corn BW, Dignam JJ. Patterns of missing mini mental status exam (MMSE) in radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) brain cancer trials. J Neurooncol. 2011;105(2):383–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloan JA, Berk L, Roscoe J, et al. Integrating patient-reported outcomes into cancer symptom management clinical trials supported by the National Cancer Institute-sponsored clinical trials networks. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5070–5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gamper EM, Nerich V, Sztankay M, et al. Evaluation of Noncompletion Bias and Long-Term Adherence in a 10-Year Patient-Reported Outcome Monitoring Program in Clinical Routine. Value Health. 2017;20(4):610–617.m 3rkjkj3 2hf 3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner-Bowker Diane M., Hao Yanni, Foley Catherine, Galipeau Nina, Mazar Iyar, Krohe Meaghan, Globe Denise & Shields Alan L. (2016) The use of patient-reported outcomes in advanced breast cancer clinical trials: a review of the published literature, Current Medical Research and Opinion, 32:10, 1709–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roydhouse JK, Gutman R, Bhatnagar V, Kluetz PG, Sridhara R, Mishra-Kalyani PS. Analyzing patient-reported outcome data when completion differs between arms in open-label trials: an application of principal stratification. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(10):1386–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown PD, Pugh SL, Laack NN, Wefel JS, Khuntia D, Meyers C, Choucair A, Fox S, Suh JH, Roberge D, Kavadi V, Bentzen SM, Mehta MP, Watkins-Bruner D. (2013). Memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuro-Oncology, 15(10):1429–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basch E High Compliance Rates With Patient-Reported Outcomes in Oncology Trials Submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(5):437–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chafe S, Moughan J, McCormick B, et al. Late toxicity and patient self-assessment of breast appearance/satisfaction on RTOG 0319: a phase 2 trial of 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy-accelerated partial breast irradiation following lumpectomy for stages I and II breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(5):854–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buysse DJ, et al. , The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 1989. 28(2): p. 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godin G, Jobin J, and Bouillon J, Assessment of leisure time exercise behavior by self-report: a concurrent validity study. Canadian Journal of Public Health Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 1986. 77(5): p. 359–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gionet NJ and Godin G, Self-reported exercise behavior of employees: a validity study. Journal of Occupational Medicine, 1989. 31(12): p. 969–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ameringer S, Elswick RK Jr, Menzies V, et al. Psychometric Evaluation of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Fatigue-Short Form Across Diverse Populations. Nurs Res 2016;65(4):279–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Land SR, Ritter MW, Costantino JP, et al. Compliance with patient-reported outcomes in multicenter clinical trials: methodologic and practical approaches. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5113–5120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mercieca-Bebber R, Friedlander M, Calvert M, et al. A systematic evaluation of compliance and reporting of patient-reported outcome endpoints in ovarian cancer randomised controlled trials: implications for generalisability and clinical practice. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;1(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little RJA, & Rubin DB Statistical analysis with missing data (2nd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. Print. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairclough D. Design and analysis of quality of life studies in clinical trials (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gwaltney CJ, Shields AL, Shiffman S. Equivalence of electronic and paper-and-pencil administration of patient-reported outcome measures: a meta-analytic review. Value Health. 2008;11(2):322–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown PD, Gondi V,Pugh SL, Tome WA, Wefel JS, Armstrong TS, Bovi JA, Robinson C, Konski A, Khuntia D, Grosshans D, Benzinger TLS, Bruner D, Gilbert MR, Roberge D, Kundapur V, Devisetty K, Shah S, Usuki K, Anderson BM, Stea B, Yoon H, Li J, Laack NN, Kruser TJ, Chmura SJ, Shi W, Deshmukh S, Mehta MP, Kachnic LA. Hippocampal Avoidance During Whole-Brain Radiotherapy Plus Memantine for Patients With Brain Metastases: Phase III Trial NRG Oncology CC001. J Clin Oncol 2020. April 1;38(10):1019–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michalski JM, Moughan J2 Purdy J, Bosch W, Bruner DW, Bahary JP, Lau H, Duclos M, Parliament M, Morton G, Hamstra D, Seider M, Lock MI, Patel M, Gay H, Vigneault E, Winter K, Sandler H. (2018). Effect of Standard vs Dose-Escalated Radiation Therapy for Patients With Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer: The NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol, 4(6):e180039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabinovitch R, Moughan J, Vicini F, Pass H, Wong J, Chafe S, Petersen I, Arthur DW, White J. (2016). Long-Term Update of NRG Oncology RTOG 0319: A Phase 1 and 2 Trial to Evaluate 3-Dimensional Conformal Radiation Therapy Confined to the Region of the Lumpectomy Cavity for Stage I and II Breast Carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, December 1;96(5):1054–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown PD, Decker PA, Rummans TA, Clark MM, Frost MH, Ballman KV, Arusell RM, Buckner JC. (2008). A prospective study of quality of life in adults with newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas: comparison of patient and caregiver ratings of quality of life. Am J Clin Oncol, 31(2):163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.