Abstract

Objectives:

Cannabidiolic acid (CBDa) is pharmacologically unique from cannabidiol (CBD), but its chemical instability poses challenges for potential clinical utility. Here, we used magnesium ions to stabilize two cannabidiolic acid-enriched hemp extracts (Mg-CBDa and Chylobinoid, the latter of which also contains minor cannabinoid constituents) and compared their anticonvulsant activities with CBD in the maximal electroshock seizure test (MES) in rats.

Methods:

Sprague-Dawley rats received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of Chylobinoid, Mg-CBDa, or CBD at varying doses at discrete time points. Rats were challenged with a 0.2 s, 60 Hz, 150 mA corneal stimulation and evaluated for resultant hindlimb tonic extension. Dose-response relationships were calculated using Probit analysis and statistical significance was assessed with a two-sample z-test.

Results:

Median effective doses (ED50) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each compound and adjusted according to percentage of CBDa (w/w): Chylobinoid: 76.7 (51.7 – 109.2) mg/kg. Mg-CBDa: 115.4 (98.8 – 140.9) mg/kg. CBD: 68.8 (56.6 – 80.0) mg/kg.

Significance:

CBDa-enriched hemp extracts exhibited dose-dependent protection in the MES model at doses comparable, but not more effective than, CBD. Chylobinoid was more effective than Mg-CBDa despite lower CBDa content. Test compounds should be compared by sub-chronic dosing in the MES test in order to assess safety and pharmacokinetic profiles. CBDa should be evaluated in pharmacoresistant and chronic animal models of epilepsy.

Keywords: Cannabidiol, Cannabidiolic acid, Cannabis, Maximal electroshock seizures, Entourage effect, Epilepsy

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite the availability of over 25 FDA-approved anticonvulsants to treat epilepsy, approximately one-third of epilepsy patients fail to achieve seizure freedom (Noonan, 2017). Recently, the use of phytocannabinoids, the molecular constituents of the Cannabis sativa plant, has gained considerable attention in the treatment of epilepsy. In June 2018, Epidiolex (GW Pharmaceuticals) became the first approved cannabis-derived drug in the United States for treating two severe forms of intractable childhood epilepsy: Dravet Syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (Sekar and Pack, 2019). However, the mechanism of action underlying the drug’s active ingredient, cannabidiol (CBD), remains unclear (Senn et al., 2020). Moreover, CBD is just one of 150 phytocannabinoids in Cannabis whose therapeutic effects remain to be fully resolved (Kinghorn et al., 2017). Indeed, experimental evidence shows that several Cannabis extracts with equivalent CBD concentrations (standardized 50% w/w) display highly variable anticonvulsant activities, suggesting that CBD is not the sole contributor to marijuana’s anticonvulsant properties (Berman et al., 2018). Growing evidence in the field supports the entourage effect, which proposes that the full neuroprotective effects of cannabis depend on synergistic interactions between dozens of its compounds (Russo, 2018, 2011).

Cannabidiolic acid (CBDa), the chemical precursor to CBD, is a relatively understudied phytocannabinoid with potential therapeutic value. For example, CBDa enhances 5-HT1A receptor activation with a significantly greater potency than CBD in rats (Bolognini et al., 2013). By increasing potassium conductance, 5-HT1A receptor activation evokes neuronal membrane voltage hyperpolarization and has anticonvulsant effects in various experimental seizure models (Theodore, 2003). Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that CBDa raises the threshold for inducing thermogenic seizures in the Scn1aRX/+ mouse model of Dravet syndrome (Anderson et al., 2019).

Despite its therapeutic promise, CBDa remains challenging to research because exposure to heat or light decarboxylates CBDa into CBD (Citti et al., 2018). The natural degradation of CBDa into CBD can be mitigated through the use of metal coordination when extracting CBDa from raw hemp. Metal coordination involves attaching a minute quantity of a pharmaceutically acceptable metal to an active pharmaceutical agent, altering its molecular properties (Jurca et al., 2017). For example, magnesium can improve a poorly absorbed drug’s solubility in aqueous solutions while maintaining favorable interactions with lipid bilayers necessary to permit efficient passage from the digestive tract to the bloodstream and the target cell (M’bitsi-Ibouily et al., 2017).

Using metal-coordination techniques, we synthesized two CBDa-enriched hemp extracts, Chylobinoid and Mg-CBDa. Chylobinoid is a partial spectrum, CBDa-enriched extract that also includes minor amounts of CBD, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCa), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and magnesium. By contrast, Mg-CBDa is a highly purified extract of CBDa coordinated to magnesium. We aimed to profile the dose-response anticonvulsant activity of Chylobinoid and Mg-CBDa in the MES test in rats compared to a CBD isolate. The MES test is an accepted model of electrically-induced seizures due to its ability to recapitulate generalized tonic-clonic seizures (Kandratavicius et al., 2014). Our results demonstrate that Chylobinoid was more effective than Mg-CBDa in reducing MES-induced seizures, consistent with the hypothesis that the anticonvulsant effects of cannabis are improved via the entourage effect.

2. METHODS

2.1. Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley CD albino rats (100–120 g, N = 186; Charles River, Raleigh, NC) were used as experimental animals for this study. All animals were allowed free access to both food (Teklad Irradiated Rodent Diet #8904; Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) and water, except during the short time they were removed from their cage for testing. All animals were housed at an ambient temperature of 25 °C and kept on a 12:12 h light-dark schedule. All animals were housed, fed, and handled in a manner consistent with the recommendations in the National Research Council publication, “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). No insecticides capable of altering hepatic drug metabolism enzymes were used in the animal facilities. Animals used in each experiment were tested only once and euthanized in accordance with the Institute of Laboratory Resources policies on the humane care of laboratory animals.

2.2. Drugs

Cannabinoid candidate drugs included a partial-spectrum CBDa-enriched compound (Chylobinoid), a high-purity magnesium-infused CBDa crystalline compound (Mg-CBDa), and cannabidiol isolate (CBD). Chylobinoid (Batch ID: PC-023) was obtained from Synthonics, Inc. (Blacksburg, VA) and contained 74.5% CBDa, 4.7% CBD, 1.9% THCa, 0.3% THC, and 3.43% magnesium (w/w). Mg-CBDa (Batch ID: MM-11098) was obtained from Synthonics, Inc. (Blacksburg, VA) and contained 92.8% CBDa, 0.2% THC, and 2.76% magnesium (w/w). CBD isolate (Batch ID: 082119) was obtained from EcoGen Laboratories (Grand Junction, CO) and contained 99.99% CBD and ≤ 0.01% THC. Cannabinoid dosing suspensions were prepared by stepwise addition of ethanol, Kolliphor® EL (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.9% saline in a ratio of 1:1:18 and mixed by vortex and placed in a sonibath. Compounds were administered by the intraperitoneal (i.p) route in a volume of 0.008 mL/g body weight in rats.

2.3. Maximal electroshock seizure (MES) test in rats

Rats were challenged with a 0.2 s, 60 Hz, 150 mA stimulus by corneal electrodes using a constant-current generator (Rodent Shocker; Hugo-Sachs Electronik, Freiberg, Germany). An electrolyte solution containing an anesthetic agent was applied to the eyes before stimulation (0.5% tetracaine HCl). An animal was considered “protected” from the MES-induced seizures when full hindlimb extension was absent (White et al., 1995). Pre-testing occurred the day prior to compound administration in order to confirm responsiveness (i.e. full tonic extension) to the MES test.

2.4. Time of Peak Effect and Median Effective Dose Determination

Before determining the median effective dose (ED50) of the investigational compounds, the time of peak effect (TPE) was determined with N = 6–8 animals/time point. Animals were treated with the compounds and evaluated at the following time points (0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0 h), or as determined empirically necessary. Quantification of the ED50 was conducted at the determined TPE in groups of N = 8 animals per dose by administering various doses of the investigational compound with the goal of establishing at least two points between the limits of 0 and 100% protection.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard error. The ED50 values, as well as the 95% confidence interval, slope of the regression line, and the SEM of the slope, were calculated by Probit analysis (Finney, 1952). ED50 values were statistically compared according to z-test methods described by Austin et al (Austin and Hux, 2002).

When comparing ED50 values in pre-clinical and clinical drug trials, it is a common misconception to assume that because the 95% confidence intervals overlap, the ED50’s of two different groups are not statistically significant from each other at the α = 0.05 level (Mancuso et al., 2001). While this statistical treatment applies when comparing one ED50 with a constant, it does not hold true when comparing two ED50 values with individual variability (Austin and Hux, 2002). Assuming that both ED50 values have similar presumed variances and their confidence intervals overlap, with a proportion of overlap being p, a two-sample ztest can be performed that results in a test statistic of:

| (1) |

In this statistical test, we reject the null hypothesis of the equality of the two ED50 values when the ztest is larger than 1.96. Hence, as long as the two 95% confidence intervals overlap by less than 29%, we will reject the null hypothesis with a P value of less than 0.05 (Austin and Hux, 2002).

Unlike our tested CBD (99.9% w/w), neither Chylobinoid nor Mg-CBDa are true CBD isolates. Therefore, we adjusted the Probit analysis by the percentage of CBDa in each compound to accurately reflect the dosages tested. Statistical comparison of the raw and adjusted ED50 values of Chylobinoid, Mg-CBDa, and CBD was performed according to Eq. 1.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Time of Peak Effect

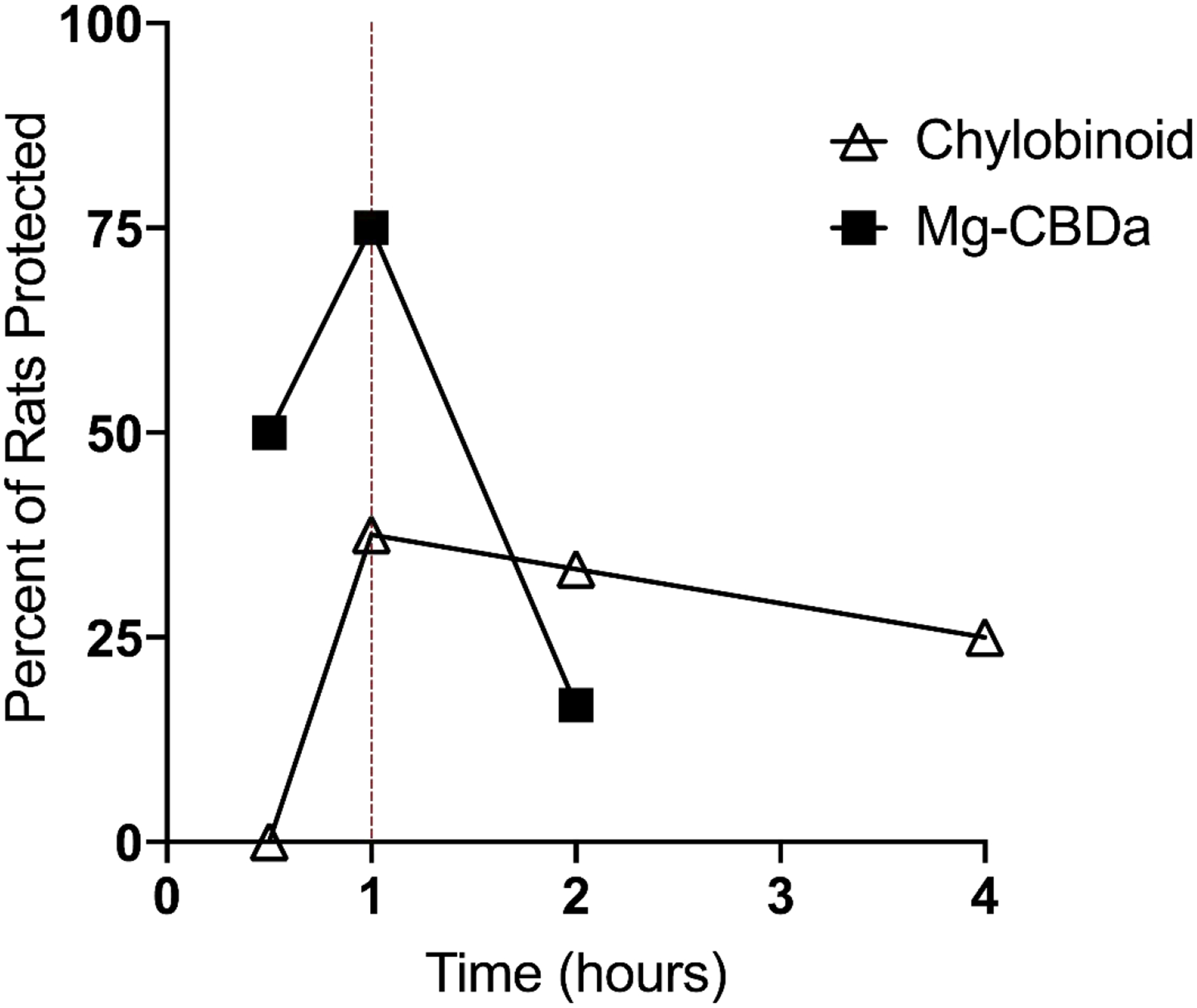

Chylobinoid was administered i.p. at a dose of 80 mg/kg at time points of 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h post-injection. Mg-CBDa was administered i.p. at a dose of 140 mg/kg at time points of 0.5 h, 1 h, and 2 h post-injection; the 4 h time point was omitted after observing the steep decline in efficacy at 2 h. Chylobinoid and Mg-CBDa both exhibited a time of peak effect at 1 h post i.p. injection (Fig. 1, Table 1). CBD was tested at a time point of 2 h, as determined in previously published experiments by the Epilepsy Therapy Screening Program (ETSP) (Klein et al., 2017).

Fig. 1. Time of peak effect (TPE) studies for Chylobinoid and Mg-CBDa.

Chylobinoid was administered i.p at a dose of 80 mg/kg and tested at time points of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 h (N = 6–8 per time point). Mg-CBDa was administered i.p at a dose of 140 mg/kg and tested at time points of 0.5, 1, and 2 h. The TPE for Mg-CBDa and Chylobinoid is 1 h for both compounds.

Table 1.

Effects of candidate drugs in rat MES test.

| Raw | Adjusted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | TPE | ED50 (mg/kg) | 95% Confidence Interval | Ztest (vs. CBD) | ED50 (mg/kg) | 95% Confidence Interval | Ztest (vs. CBD) |

| Chylobi noid | 1h | 102.97 ± 16.44 | [69.40, 146.33] | 2.389* | 76.71 ± 12.25 | [51.70, 109.01] | 1.402 |

| Mg-CBDa | lh | 124.34 ± 9.38 | [106.42, 151.84] | 4.383* | 115.39 ± 8.70 | [98.76, 140.90] | 4.005* |

| CBD | 2h | 68.78 ± 4.91 | [56.62, 80.02] | - | - | - | - |

Time of peak effect, ED50, and 95% confidence interval of ED50 were determined. Adjusted ED50 and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to standardize for CBDa content in Chylobinoid and Mg-CBDa. Statistical cross-comparisons of raw and adjusted median effective doses (ED50) of Chylobinoid, Mg-CBDa, and CBD.

= P < 0.05.

3.2. Median Effective Dose

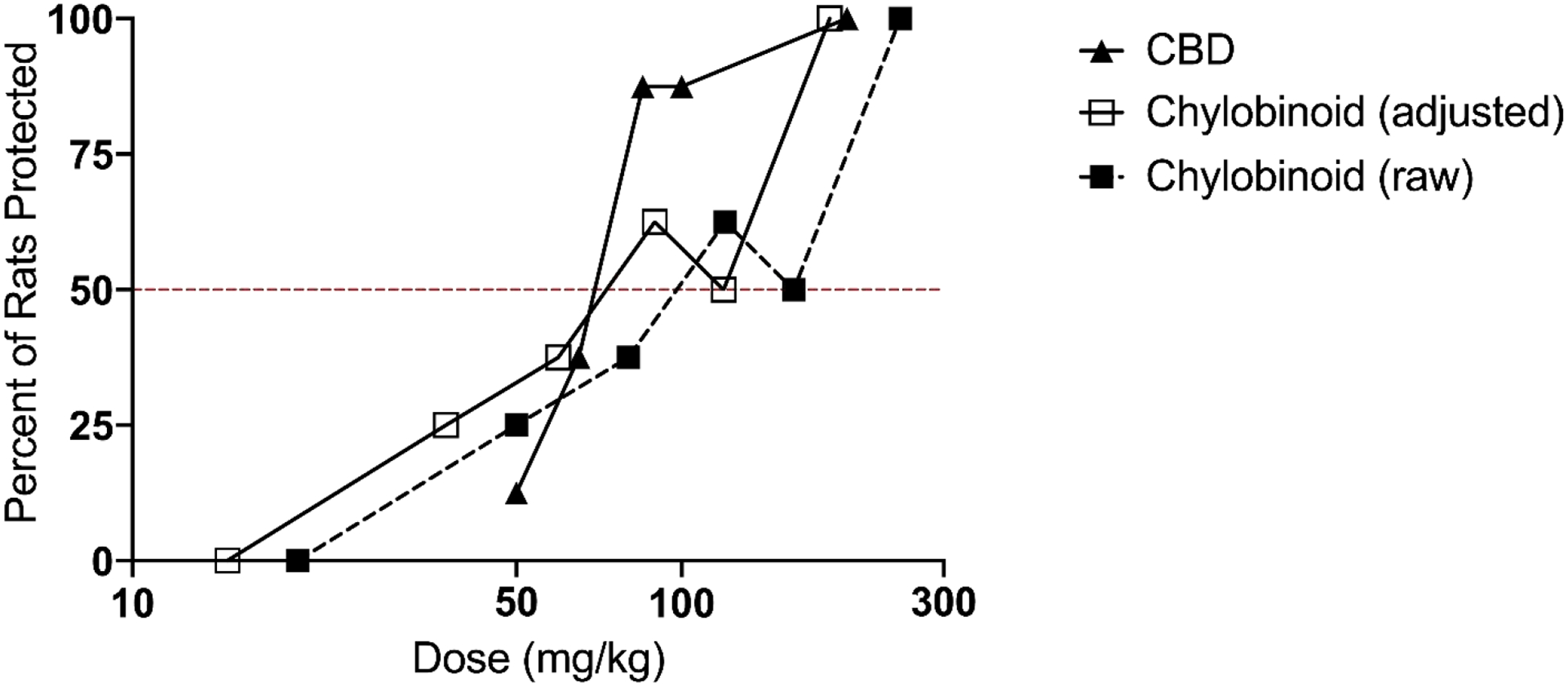

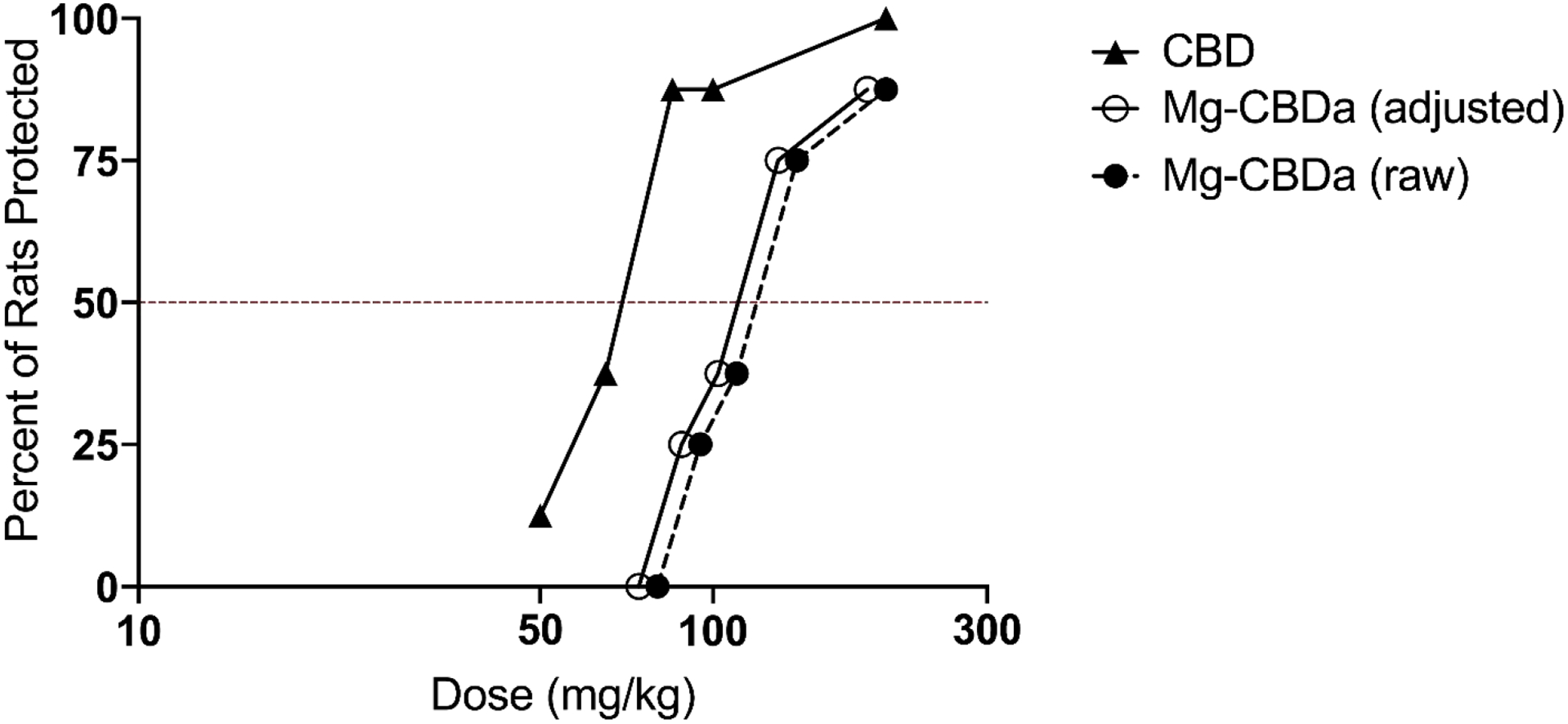

Dose-response quantification studies for Chylobinoid and Mg-CBDa were performed at the 1 h time-point to determine ED50 values. Chylobinoid, Mg-CBDa, and CBD exhibited dose-dependent protection at well-tolerated doses in the MES Model (Figs. 2 and 3). Table 1 shows the raw and adjusted ED50 values and z-test results for each compound.

Fig 2. Dose-response curve of CBD and Chylobinoid in the rat MES test.

Chylobinoid and CBD were administered i.p. 1 hour and 2 hours prior to stimulation, respectively. Total animals used were N = 48 for Chylobinoid, N = 40 for CBD. The percent of rats protected is shown for each dose, with each point on the graph representing a group of N = 8 animals. ED50’s were calculated per probit analysis to be 102.97 mg/kg (Chylobinoid) and 68.78 mg/kg (CBD). The adjusted graph represents Chylobinoid dose standardized for 74.5% CBDa, with resulting ED50 of 76.61 mg/kg.

Fig 3. Dose-response curve of CBD and Mg-CBDa in the rat MES test.

Mg-CBDa and CBD were administered i.p. 1 h and 2 h prior to stimulation, respectively. Total animals used were N = 40 for Chylobinoid, N = 40 for CBD. The percent of rats protected is shown for each dose, with each point on the graph representing a group of N = 8 animals. ED50’s were calculated per probit analysis to be 124.34 mg/kg (Mg-CBDa) and 68.78 mg/kg (CBD). The adjusted graph represents Mg-CBDa doses standardized for 92.8% CBDa, with resulting ED50 of 115.39 mg/kg.

4. DISCUSSION

Chylobinoid is a magnesium-stabilized cannabinoid complex enriched with 74.5% CBDa (w/w) but contains minor cannabinoid constituents that may also have pharmacologically active properties (Gaston and Friedman, 2017). By contrast, Mg-CBDa is enriched with a greater percentage of CBDa (92.8% w/w) and does not contain minor cannabinoid constituents. All tested cannabinoids exhibited anticonvulsant activity in the MES test in rats, indicated by the ability of each to protect an increasing number of animals from seizures as the dosage was increased and 100% of animals at the highest dose tested.

Adjustment for CBDa content in Chylobinoid and Mg-CBDa resolved differences in efficacy between the two compounds, relative to CBD. Mg-CBDa, a relatively pure form of CBDa, is not as potent as CBD in protecting rats from seizures in the MES model, even when adjusted for CBDa content. By contrast, Chylobinoid exhibits potency at a level statistically similar to CBD when standardized for the amount of CBDa. Moreover, when adjusted for CBDa content, the ED50 value of Chylobinoid was significantly lower than that of Mg-CBDa despite Mg-CBDa containing a larger proportion of CBDa.

The augmentation of CBDa’s potency in Chylobinoid compared to Mg-CBDa may be attributed to favorable interactions between CBDa and the minor cannabinoid constituents contained in the Chylobinoid compound. The concept of cannabinoid synergy was first proposed in 1998 by Raphael Mechoulam and Shimon Ben-Shabat. They posited that the endocannabinoid system demonstrated an “entourage effect” in which a variety of “inactive” metabolites could significantly increase the activity of the primary endogenous cannabinoids, anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (Ben-Shabat et al., 1998). Indeed, clinical differences between whole-plant extracts and single-cannabinoid isolates have been widely documented. A recent meta-analysis of 11 studies with 670 patients in aggregate showed that 71% of patients saw seizure improvement using CBD-enriched Cannabis extracts versus 36% on CBD isolate (Pamplona et al., 2018). Furthermore, the average dose described by patients taking CBD-enriched extracts was over 4 times lower than the dose reported by patients taking purified CBD. However, identifying the precise constituents that confer therapeutic advantage has proven difficult because an average sample of Cannabis contains 565 compounds and 150 cannabinoids (Kinghorn et al., 2017). In this study, the CBDa-enriched Chylobinoid is accompanied by significant amounts of only three other cannabinoid constituents in known concentrations: CBD (4.7%), THCa (1.9%), and THC (0.3%). The partial-spectrum nature of Chylobinoid significantly reduces the number of possible therapeutic constituents and provides preclinical evidence in support of the entourage effect in mitigating seizures in the MES model.

Additionally, differences in anticonvulsant efficacy between Mg-CBDa and Chylobinoid may result from differences in pharmacokinetic properties. The pharmacokinetic parameters of CBDa can depend on the vehicle preparation. Anderson et al. demonstrated that CBDa achieves a brain-plasma ratio about 50 times greater using a 1:1:18 ethanol-Tween 80-saline vehicle versus a vegetable oil vehicle (2019). To maximize brain penetrance, we used a vehicle similar to ethanol-Tween 80-saline, but substituted Tween 80 with Kolliphor® EL (both compounds are non-ionic surfactants). All test compounds received identical vehicle preparation to control for vehicle effects on pharmacokinetics. Nonetheless, it remains possible that Mg-CBDa and Chylobinoid exhibit different brain penetrance independent of vehicle preparation, warranting future investigation of the pharmacokinetic profiles of these compounds.

The mechanisms of action of CBD and CBDa in relation to anticonvulsant activity are not well understood, but several possible molecular targets have been suggested (Senn et al., 2020). Unlike THC, CBD is a weak, negative allosteric modulator of the CB1 receptor and its activity in the MES model has been shown to be CB1-independent (Laprairie et al., 2015). In vitro studies have shown that CBD reduces neuronal excitability by inhibiting voltage-gated sodium channels, a feature shared by some anticonvulsants (Patel et al., 2016). Multiple putative mechanisms of action of CBD have been discussed including agonism of serotonergic 5-HT1A receptors, modulation of NMDA receptors, enhancement of adenosine signaling, and activation of GABA receptors.

Although the mechanisms of action for CBDa are poorly understood relative to CBD, evidence suggests that CBDa may agonize 5-HT1A receptors (Bolognini et al., 2013; Pertwee et al., 2018). These studies demonstrate that CBDa enhances the activation of both rat brainstem 5-HT1A receptors and human 5-HT1A receptors in vitro, and produces a 5-HT1A receptor-mediated antiemetic response in rats in vivo. 5-HT1A receptor activation elicits membrane hyperpolarization responses related to increased potassium conductance and has an anticonvulsant effect in various experimental seizure models (Theodore, 2003). Additionally, 5-HT1A receptor agonists may exhibit protective effects in rat models of convulsive seizures, particularly in PTZ- and KA-induced seizures, via a mechanism partially or fully mediated by 5-HT1A receptors (López-Meraz et al., 2005). Future studies should evaluate whether the anticonvulsant properties of CBDa are 5-HT1A mediated.

No single animal seizure model can fully capture the clinical manifestation of epilepsy. Our study used only one animal model, which while robust, captures only one facet of the anticonvulsant profile of a compound, therefore limiting broad conclusions. Although Chylobinoid and CBD exhibit comparable anticonvulsant properties in the MES test, ED50 values reflect only one property of a drug’s anticonvulsant profile. Follow up toxicity studies are necessary to determine the protective index (PI) of each cannabinoid compound, defined as the ratio of TD50 (median toxic dose) to ED50. Notably, significant motor impairment was observed at the highest dose of 250 mg/kg for Chylobinoid. Future studies incorporating additional acute animal models (e.g. 6 Hz psychomotor seizure test), sub-chronic dosing in the MES test, chronic animal models (e.g. the hippocampal kindled rat), and toxicity studies would provide a greater understanding of anticonvulsant properties and therapeutic relevance of these compounds. Nonetheless, our results provide the motivation for further pursuit.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our study shows that CBDa-enriched hemp extracts demonstrate anticonvulsant properties similar to CBD in an acute animal model of seizures. Furthermore, the inclusion of minor cannabinoid constituents with CBDa significantly enhances its potency, supporting the entourage effect theory of cannabinoid synergy.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Cannabidiolic acid (CBDa) is anticonvulsant in rat maximal electroshock seizure test

Inclusion of minor cannabinoid constituents modifies CBDa’s potency

CBDa exhibits anticonvulsant effects comparable to cannabidiol (CBD)

Augmentation of CBDa’s potency is consistent with the entourage effect

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our team would like to thank Dr. Thomas Piccariello and Michaela Mulhare of Synthonics, Inc. and Jan Politis of ChyloCure for generously providing Mg-CBDa and Chylobinoid for use in the aforementioned experiments as well as their advice on properly storing and preparing the compounds.

FUNDING

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Health under Award Number R01NS099586-01.

Abbreviations:

- CBDa

cannabidiolic acid

- CBD

cannabidiol

- MES

maximal electroshock seizure test

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- ED50

median effective dose

- THCa

tetrahydrocannabinolic acid

- THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- TPE

time of peak effect

- ETSP

Epilepsy Therapy Screening Program

- PI

protective index

- TD50

median toxic dose

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTEREST

All authors declare that the study was done in the absence of any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Austin PC, Hux JE, 2002. A brief note on overlapping confidence intervals. J. Vasc. Surg 36, 194–195. 10.1067/mva.2002.125015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LL, Low IK, Banister SD, McGregor IS, Arnold JC, 2019. Pharmacokinetics of Phytocannabinoid Acids and Anticonvulsant Effect of Cannabidiolic Acid in a Mouse Model of Dravet Syndrome. J. Nat. Prod 82, 3047–3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shabat S, Fride E, Sheskin T, Tamiri T, Rhee MH, Vogel Z, Bisogno T, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V, Mechoulam R, 1998. An entourage effect: inactive endogenous fatty acid glycerol esters enhance 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol cannabinoid activity. Eur. J. Pharmacol 353, 23–31. 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00392-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman P, Futoran K, Lewitus GM, Mukha D, Benami M, Shlomi T, Meiri D, 2018. A new ESI-LC/MS approach for comprehensive metabolic profiling of phytocannabinoids in Cannabis. Sci. Rep. 8 10.1038/s41598-018-32651-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolognini D, Rock EM, Cluny NL, Cascio MG, Limebeer CL, Duncan M, Stott CG, Javid FA, Parker LA, Pertwee RG, 2013. Cannabidiolic acid prevents vomiting in Suncus murinus and nausea-induced behaviour in rats by enhancing 5-HT1A receptor activation. Br. J. Pharmacol 168, 1456–1470. 10.1111/bph.12043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citti C, Pacchetti B, Vandelli MA, Forni F, Cannazza G, 2018. Analysis of cannabinoids in commercial hemp seed oil and decarboxylation kinetics studies of cannabidiolic acid (CBDA). J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 149, 532–540. 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney DJ, 1952. Probit analysis: A statistical treatment of the sigmoid response curve, 2nd ed, Probit analysis: A statistical treatment of the sigmoid response curve, 2nd ed Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, US. [Google Scholar]

- Gaston TE, Friedman D, 2017. Pharmacology of cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav., Cannabinoids and Epilepsy 70, 313–318. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurca T, Marian E, Vicaş LG, Mureşan ME, Fritea L, 2017. Metal Complexes of Pharmaceutical Substances. Spectrosc. Anal. - Dev. Appl 10.5772/65390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kandratavicius L, Balista PA, Lopes-Aguiar C, Ruggiero RN, Umeoka EH, Garcia-Cairasco N, Bueno-Junior LS, Leite JP, 2014. Animal models of epilepsy: use and limitations. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat 10, 1693–1705. 10.2147/NDT.S50371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinghorn AD, Falk H, Gibbons S, Kobayashi J (Eds.), 2017. Phytocannabinoids: Unraveling the Complex Chemistry and Pharmacology of Cannabis sativa, Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products. Springer International Publishing; 10.1007/978-3-319-45541-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BD, Jacobson CA, Metcalf CS, Smith MD, Wilcox KS, Hampson AJ, Kehne JH, 2017. Evaluation of Cannabidiol in Animal Seizure Models by the Epilepsy Therapy Screening Program (ETSP). Neurochem. Res 42, 1939–1948. 10.1007/s11064-017-2287-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laprairie RB, Bagher AM, Kelly MEM, Denovan-Wright EM, 2015. Cannabidiol is a negative allosteric modulator of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol 172, 4790–4805. 10.1111/bph.13250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Meraz M-L, González-Trujano M-E, Neri-Bazán L, Hong E, Rocha LL, 2005. 5-HT1A receptor agonists modify epileptic seizures in three experimental models in rats. Neuropharmacology 49, 367–375. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso CA, Peterson MG, Charlson ME, 2001. Comparing discriminative validity between a disease-specific and a general health scale in patients with moderate asthma. J. Clin. Epidemiol 54, 263–274. 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00307-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- M’bitsi-Ibouily GC, Marimuthu T, Kumar P, du Toit LC, Choonara YE, Kondiah PPD, Pillay V, 2017. Outlook on the Application of Metal-Liganded Bioactives for Stimuli-Responsive Release. Mol. J. Synth. Chem. Nat. Prod. Chem 22 10.3390/molecules22122065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan D, 2017. The Epilepsy Dilemma. Sci. Am 316, 28–29. 10.1038/scientificamerican0417-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamplona FA, da Silva LR, Coan AC, 2018. Potential Clinical Benefits of CBD-Rich Cannabis Extracts Over Purified CBD in Treatment-Resistant Epilepsy: Observational Data Meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 9 10.3389/fneur.2018.00759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RR, Barbosa C, Brustovetsky T, Brustovetsky N, Cummins TR, 2016. Aberrant epilepsy-associated mutant Nav1.6 sodium channel activity can be targeted with cannabidiol. Brain J. Neurol 139, 2164–2181. 10.1093/brain/aww129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG, Rock EM, Guenther K, Limebeer CL, Stevenson LA, Haj C, Smoum R, Parker LA, Mechoulam R, 2018. Cannabidiolic acid methyl ester, a stable synthetic analogue of cannabidiolic acid, can produce 5- HT1A receptor- mediated suppression of nausea and anxiety in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol 175, 100–112. 10.1111/bph.14073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB, 2018. The Case for the Entourage Effect and Conventional Breeding of Clinical Cannabis: No “Strain,” No Gain. Front. Plant Sci 9, 1969 10.3389/fpls.2018.01969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo EB, 2011. Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects. Br. J. Pharmacol 163, 1344–1364. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekar K, Pack A, 2019. Epidiolex as adjunct therapy for treatment of refractory epilepsy: a comprehensive review with a focus on adverse effects. F1000Research 8 10.12688/f1000research.16515.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn L, Cannazza G, Biagini G, 2020. Receptors and Channels Possibly Mediating the Effects of Phytocannabinoids on Seizures and Epilepsy. Pharmaceuticals 13 10.3390/ph13080174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Bebin EM, 2014. Cannabis, cannabidiol, and epilepsy--from receptors to clinical response. Epilepsy Behav. EB 41, 277–282. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.08.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodore WH, 2003. Does serotonin play a role in epilepsy? Epilepsy Curr 3, 173–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HS, Johnson M, Wolf HH, Kupferberg HJ, 1995. The early identification of anticonvulsant activity: role of the maximal electroshock and subcutaneous pentylenetetrazol seizure models. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci 16, 73–77. 10.1007/BF02229077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.