Abstract

Background:

Prevalence of cannabis use has been increasing among select subgroups in the US; however, trend analyses typically examine prevalence of use across years. We sought to determine whether there is seasonal variation in use.

Methods:

We conducted a secondary analysis of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health from 2015 to 2019 (N=282,768), a repeated cross-sectional survey of nationally representative probability samples of noninstitutionalized populations age ≥12 in the US. Quarterly trends in any past-month cannabis use were estimated.

Results:

Prevalence of past-month cannabis use increased significantly from 2015 to 2019 from 8.3% to 11.5%, a 38.2% increase (P<0.001). Prevalence increased across calendar quarters on average from 8.9% in January-March to 10.1% in October-December, a 13.0% increase (P<0.001). Controlling for survey year and participant demographics, each subsequent quarter was associated with a 6% increase in odds for use (aOR=1.06, 95% CI: 1.04–1.07). There were significant increases by quarter among all subgroups of sex, race/ethnicity, education, and among most adult age groups (Ps<0.05), with a 52.7% increase among those age ≥65. Prevalence also significantly increased among those without a medical cannabis prescription and those not proxy-diagnosed with cannabis use disorder (Ps<0.01), suggesting recreational use may be driving increases more than medical or more chronic use. Those reporting past-year LSD or blunt use in particular were more likely to report higher prevalence of use later in the year (a 4.9% and 3.3% absolute increase, respectively; Ps<0.05).

Conclusion:

The prevalence of cannabis use increases throughout the year, independently of annual increases.

Keywords: cannabis, substance use, epidemiology, seasonal variation

1. Introduction

Cannabis policy and trends in cannabis use are rapidly shifting in the United States (US). As of November 2020, 15 states have legalized or voted to legalize recreational use. Prevalence of cannabis use has also increased significantly among individuals in select age groups and in states with more liberal cannabis policies, as has frequency of use and prevalence of cannabis use disorder (CAD) (Cerdá et al., 2019; Cerdá et al., 2012; Han and Palamar, 2020; Hasin et al., 2017). Methods of use have also been shifting, with vaping of cannabis increasing greatly in recent years (Miech et al., 2020). Extensive research has examined trends in cannabis use over time but has been largely limited to annual prevalence estimates. Analysis of trends by season or calendar quarter can provide greater nuance to the epidemiology behind a ubiquitous drug whose use will likely continue to grow.

Literature on seasonal variation in use of cannabis and other illegal drugs is sparse. Of the few studies examining seasonality in use among nationally representative samples, all have focused on initiation of use. These studies suggest that summer months have the highest percentage of initiation for tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, LSD, and ecstasy, particularly among adolescents and college students (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [CBHSQ], 2012; Lipari, 2015; Palamar et al., 2019). Although cannabis is more likely to be initiated in the summer than in other seasons, little is known about intra-year patterns of use.

Given the legalization of cannabis use across the US and increases in use, it could prove beneficial to determine whether seasonal patterns in use exist. Alcohol and cigarette use show seasonal variations that are relevant for informing intervention strategies (Chandra et al., 2011; Knudsen and Skogen, 2015; Momperousse et al., 2007). For example, studies on the effectiveness of alcohol drinking prevention efforts for college students have recommended that targeted interventions begin taking place during the summer months (Borsari et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2016). Similarly, findings on the temporal nature of alcohol use and alcohol-related road accidents have led to the conclusion that prevention efforts, such as police monitoring, may be more effective if enforced during specific windows of time, such as Friday and Saturday nights throughout the year and workdays during summer months (Foster et al., 2015). Others focusing on the seasonal nature of tobacco use advocate increased advertising and awareness efforts for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) at specific times of the year—based on the fact that demand for NRT appears to be responsive to advertising campaigns (Tauras et al., 2005)—in order to reduce seasonal under- or over-capacity at cessation clinics (Brown et al., 2014; Veldhuizen et al., 2020). Similar knowledge on cannabis use can aid clinicians in preparing measures for timely screening and counseling of patients on health risks and benefits. In this study, we use national data to examine trends in quarterly cannabis use throughout the calendar year in the US.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

We examined data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), a cross-sectional nationally representative survey of non-institutionalized individuals aged ≥12 in the US. The sample each year is obtained through a multistage design. Census tracts are first selected in each of the 50 states and within the District of Columbia, and then segments within each tract are randomly assigned to a year and quarter within year for data collection (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2020). Dwellings within segments and then participants are selected. Surveys are administered via computer-assisted interviewing which are conducted by an interviewer using audio-computer-assisted interviewing. We focused on data collected from the most recent five cohorts (2015–2019). The total sample size was 282,768 for combined cohorts and the weighted interview response rates ranged from 64.9% to 68.4%.

2.2. Measures

We focused on participant demographic characteristics and a variety of drug use behaviors in order to obtain a picture of potential shifts in correlates of cannabis use. Participants were asked about their age, sex, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment. With respect to cannabis use, they were asked whether they used cannabis (“marijuana” or “hashish”) in the past year (coded as yes vs. no). It was explained that marijuana is also called “pot” or “grass” and that it is usually smoked in cigarettes (called “joints”) or in a pipe, but it can also be cooked in food. It was also mentioned that hashish is often called “hash” and that it is often smoked in a pipe or used as hash oil. Participants were also asked if they had used any of these forms of cannabis in the past month via a single question (coded as yes vs. no), and in a later section they were asked about past-year and past-month blunt use, which was defined as smoking cannabis in a cigar. Those reporting past-year cannabis use were asked whether their recent use was recommended by a doctor or other healthcare professional. NSDUH also provided a variable indicating whether medical use of cannabis was legal in the participants’ state during the time of interview. Those reporting past-year or past-month use were asked about frequency of past-year and/or past-month use (data provided by NSDUH as ordinal variables). Those reporting past-year use were also asked questions to indicate whether they met criteria for proxy diagnosis of cannabis abuse or dependence in the past year using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition criteria. Those meeting criteria for either were coded as having CAD (Philbin et al., 2019).

With respect to other drug use, participants were asked about past-year use of tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, LSD, ecstasy, methamphetamine, heroin, and misuse of prescription opioids, stimulants, and tranquilizers. Misuse is defined by NSDUH as using a drug in any way not directed by a physician, including use without a prescription, more often, longer, or in greater amounts than directed to use them, or use in any other way not directed to use. We focused particularly on past-year use of cannabis and other drug-related variables when possible, as wider timeframes allow for these behaviors to occur before past-month cannabis use and not only within a one-month timeframe. Participants were also asked questions via the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence to determine whether they were dependent on nicotine.

2.3. Analyses

We first examined participant characteristics and compared each characteristic according to the quarter in which they were surveyed to determine whether each characteristic was homogeneous throughout the year. We focused on aggregated annual data and used Rao-Scott chi-square to test whether percentages were homogeneous across quarters (Heeringa et al., 2010). We then estimated past-month use of cannabis within each year and within each quarter within each year. Quarters in which interviews were conducted were pre-defined by NSDUH as January-March (Quarter 1), April-June (Quarter 2), July-September (Quarter 3), and October-December (Quarter 4). Next, we used logistic regression to determine whether quarters (as a count variable) were associated with past-month cannabis use while controlling for survey year and participant demographics. We then estimated prevalence of use within each quarter using aggregated data from all years—for the full sample and stratified by demographic and drug use characteristics. Using similar analyses, we examined whether there were trends in past-month frequency of use and past-month blunt use with the sample limited to those reporting past-month cannabis use. We calculated the absolute and relative change in prevalence across quarters and estimated log-linear associations between use and quarter. We utilized sample weights to account for the complex survey design, non-response, selection probability, and population distribution. Stata 13 SE (StataCorp, 2013) was used to analyze all data and Taylor series estimation methods were used to provide accurate standard errors (Heeringa et al., 2010). This secondary analysis was exempt from review by the New York University institutional review board.

3. Results

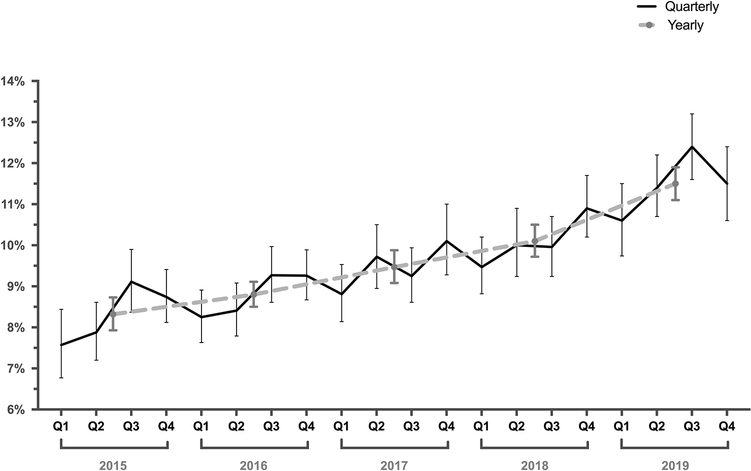

Sample characteristics—aggregated by year and stratified by quarter—are presented in Table 1. Demographic characteristics remained consistent across quarters, but significant differences were detected with respect to residing in a state where medical cannabis is legal, number of days cannabis was used in the past year, and past-year use of alcohol and LSD (Ps<0.05). Prevalence of past-month cannabis use increased significantly across years from 8.3% to 11.5%, a 38.2% increase (P<0.001). Within years, prevalence increased across quarters on average from 8.9% in Quarter 1 to 10.1% in Quarter 4, a 13.0% relative increase (P<0.001; Fig. 1). Supplemental Table 1 presents a table of all quarterly and annual estimates. Controlling for survey year and participant demographic characteristics, each subsequent quarter (compared to Quarter 1) was associated with a 6% increase in odds for use (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=1.06, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04–1.07).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, 2015–2019

| Characteristic | Weighted % (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | Quarter 1 (January-March) | Quarter 2 (April-June) | Quarter 3 (July-September) | Quarter 4 (October-December) | P | |

| Age | 0.072 | |||||

| 12–17 | 9.2 (9.0–9.3) | 9.2 (9.0–9.5) | 9.1 (8.8–9.3) | 9.1 (8.8–9.3) | 9.3 (9.1–9.6) | |

| 18–25 | 12.6 (12.5–12.8) | 13.0 (12.5–13.5) | 12.4 (12.0–12.8) | 12.3 (12.1–12.6) | 12.8 (12.4–13.2) | |

| 26–34 | 14.5 (14.3–14.7) | 14.4 (13.9–14.9) | 14.5 (14.2–14.9) | 14.9 (14.5–15.2) | 14.3 (13.9–14.7) | |

| 35–49 | 22.4 (22.1–22.7) | 22.9 (22.5–23.4) | 22.0 (21.5–22.6) | 22.1 (21.7–22.7) | 22.5 (22.1–22.9) | |

| 50–64 | 23.0 (22.6–23.3) | 22.7 (22.1–23.2) | 23.6 (22.9–24.2) | 23.0 (22.4–23.7) | 22.6 (21.9–23.3) | |

| ≥65 | 18.3 (18.0–18.7) | 17.8 (17.1–18.5) | 18.4 (17.7–19.2) | 18.6 (18.0–19.1) | 18.5 (17.8–19.2) | |

| Sex | 0.835 | |||||

| Male | 48.5 (48.2–48.8) | 48.5 (48.0–49.1) | 48.5 (47.9–49.1) | 48.3 (47.7–48.9) | 48.7 (48.0–49.3) | |

| Female | 51.5 (51.2–51.8) | 51.5 (50.9–52.0) | 51.5 (50.9–52.1) | 51.7 (51.1–52.3) | 51.3 (50.7–52.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.080 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 62.8 (62.3–63.3) | 63.7 (62.6–64.8) | 61.9 (60.9–63.0) | 62.2 (61.2–63.1) | 63.6 (62.7–64.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.0 (11.7–12.4) | 11.3 (10.6–12.1) | 12.6 (11.9–13.2) | 12.6 (11.8–13.3) | 11.6 (10.9–12.4) | |

| Hispanic | 16.8 (16.4–17.2) | 16.8 (16.2–17.4) | 17.2 (16.5–17.9) | 16.5 (16.0–17.1) | 16.6 (15.5–17.6) | |

| Asian | 5.6 (5.4–5.8) | 5.4 (5.0–5.9) | 5.5 (5.1–5.9) | 6.0 (5.5–6.5) | 5.5 (5.0–6.1) | |

| Other race/ethnicity | 2.8 (2.7–2.9) | 2.7 (2.6–2.9) | 2.9 (2.7–3.1) | 2.8 (2.6–3.1) | 2.7 (2.6–2.9) | |

| Education | 0.422 | |||||

| High school or less | 37.6 (37.1–38.0) | 37.7 (36.8–38.6) | 37.5 (36.8–38.2) | 37.3 (36.4–38.2) | 37.7 (36.9–38.4) | |

| Some college | 30.8 (30.5–31.2) | 30.7 (30.2–31.3) | 30.5 (30.0–31.1) | 30.7 (30.0–31.4) | 31.4 (30.7–32.1) | |

| College degree or more | 31.6 (31.1–32.1) | 31.5 (30.7–32.4) | 32.0 (31.2–32.8) | 32.0 (30.9–33.1) | 30.9 (30.0–31.8) | |

| Reside in State Where Medical Cannabis Use is Legal | 0.001 | |||||

| No | 41.5 (41.1–41.9) | 42.3 (41.8–42.9) | 42.1 (41.5–42.8) | 41.1 (40.3–41.8) | 40.4 (39.4–41.3) | |

| Yes | 58.5 (58.1–58.9) | 57.7 (57.1–58.2) | 57.9 (57.2–58.5) | 58.9 (58.2–59.7) | 59.6 (58.7–60.6) | |

| Prescribed Medical Cannabis in Past Year | 0.037 | |||||

| No | 98.2 (98.1–98.3) | 98.4 (98.3–98.6) | 98.2 (98.1–98.3) | 98.1 (97.9–98.3) | 98.1 (98.0–98.3) | |

| Yes | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | 1.9 (1.7–2.0) | |

| Number of Days Used Cannabis in Past Year | <0.001 | |||||

| 0 | 84.8 (84.6–85.0) | 85.4 (85.0–85.7) | 85.0 (84.7–85.4) | 84.5 (84.1–84.9) | 84.2 (83.8–84.7) | |

| 1–11 | 4.5 (4.4–4.6) | 4.5 (4.3–4.8) | 4.4 (4.3–4.7) | 4.5 (4.2–4.7) | 4.6 (4.4–4.8) | |

| 12–49 | 2.6 (2.5–2.7) | 2.6 (2.4–2.8) | 2.6 (2.5–2.8) | 2.6 (2.5–2.8) | 2.6 (2.4–2.8) | |

| 50–99 | 1.5 (1.4–1.5) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | |

| 100–299 | 3.7 (3.6–3.8) | 3.5 (3.3–3.7) | 3.4 (3.3–3.6) | 3.9 (3.7–4.1) | 3.8 (3.6–4.1) | |

| 300–365 | 3.0 (2.9–3.0) | 2.6 (2.5–2.8) | 3.0 (2.8–3.1) | 3.0 (2.8–3.2) | 3.2 (3.0–3.4) | |

| Past-Year Cannabis Use Disorder | 0.553 | |||||

| No | 98.4 (98.4–98.5) | 98.4 (98.3–98.6) | 98.5 (98.4–98.6) | 98.4 (98.3–98.5) | 98.4 (98.2–98.5) | |

| Yes | 1.6 (1.5–1.6) | 1.6 (1.4–1.7) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | 1.6 (1.5–1.8) | |

| Past-Year Blunt Use | 0.056 | |||||

| No | 93.3 (93.2–93.4) | 93.5 (93.2–93.7) | 93.4 (93.2–93.6) | 93.2 (92.9–93.5) | 93.0 (92.8–93.3) | |

| Yes | 6.7 (6.6–6.8) | 6.5 (6.3–6.8) | 6.6 (6.4–6.8) | 6.8 (6.5–7.1) | 7.0 (6.7–7.2) | |

| Past-Year Other Drug Use | ||||||

| Tobacco | 27.7 (27.3–28.0) | 28.0 (27.4–28.7) | 27.3 (26.6–28.0) | 27.4 (27.0–27.9) | 27.9 (27.4–28.5) | 0.189 |

| Alcohol | 65.4 (65.1–65.7) | 66.2 (65.5–66.9) | 65.0 (64.5–65.5) | 65.1 (64.5–65.7) | 65.1 (64.5–65.7) | 0.020 |

| Cocaine | 2.0 (1.9–2.1) | 1.9 (1.8–2.1) | 1.9 (1.8–2.1) | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | 2.0 (1.8–2.1) | 0.261 |

| LSD | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.7–0.8) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.015 |

| Ecstasy (MDMA/Molly) | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.520 |

| Methamphetamine | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.205 |

| Heroin | 0.3 (0.3–0.3) | 0.3 (0.2–0.3) | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) | 0.3 (0.2–0.3) | 0.3 (0.3–0.4) | 0.105 |

| Prescription Opioids | 4.0 (3.9–4.1) | 4.0 (3.8–4.2) | 4.0 (3.8–4.2) | 4.2 (4.0–4.5) | 3.9 (3.7–4.0) | 0.115 |

| Prescription Stimulants | 2.0 (1.9–2.1) | 2.0 (1.9–2.1) | 2.0 (1.9–2.2) | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | 2.1 (1.9–2.2) | 0.411 |

| Prescription Tranquilizers | 2.2 (2.1–2.3) | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | 2.2 (2.0–2.3) | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | 2.2 (2.1–2.4) | 0.432 |

| Nicotine Dependence | 8.6 (8.4–8.8) | 8.7 (8.4–9.0) | 8.5 (8.1–8.9) | 8.4 (8.0–8.8) | 8.7 (8.4–9.1) | 0.455 |

Aggregated data from the 2015–2019 US National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) among respondents ages ≥12 (n=282,768). Quarters refer to aggregated data from all years; for example, Quarter 1 contains data from Quarter 1 for all five years of data combined. Prescription opioids, stimulants, and tranquilizers refer to misuse. CI = confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

Yearly and Quarterly Trends in Past-Month Cannabis Use in the United States, 2015–2019.

Table 2 presents prevalence trends by quarters stratified by participant demographic and drug use characteristics. There were significant increases among all adult age groups other than those age 50–64 (Ps<0.05) and a 52.7% relative increase among those aged ≥65. There were significant increases among all subgroups of sex, race/ethnicity, and education (Ps<0.01). Among these increases, those identifying as other or mixed race and those with a college degree or higher were particularly likely to report higher prevalence of use later in the year, with individuals in these groups reporting higher prevalence of use later in the year by 25.1% and 23.2%, respectively. Significant increases also occurred among those who reside and do not reside in states allowing medical cannabis use and among those not proxy-diagnosed with CAD (Ps<0.05). There was a relative increase by 11.7% across seasons among those who used cannabis in the past year and were not recommended to use by a doctor (from 7.8% in Quarter 1 to 8.7% in Quarter 4; P<0.001) and an absolute increase by 3.3% among those reporting past-year blunt use (from 71.7% to 75.0%; P<0.001)

Table 2.

Quarterly Trends in Past-Month Cannabis Use by Demographic and Substance Use Characteristics, 2015–2019

| Weighted % (95% CI) | % Change from Quarter 1 to Quarter 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Quarter 1 (January-March) | Quarter 2 (April-June) | Quarter 3 (July-September) | Quarter 4 (October-December) | Absolute Change | Relative Change | Linear Trend P Value |

| Past-month cannabis use | 8.9 (8.7–9.3) | 9.5 (9.2–9.8) | 10.0 (9.7–10.3) | 10.1 (9.8–10.5) | 1.2 | 13.0 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||||||

| 12–17 | 6.9 (6.4–7.4) | 6.7 (6.3–7.2) | 7.1 (6.5–7.7) | 6.7 (6.2–7.2) | −0.2 | −2.9 | 0.803 |

| 18–25 | 20.3 (19.5–21.2) | 21.4 (20.6–22.3) | 22.1 (21.2–22.9) | 22.2 (21.4–23.0) | 1.9 | 9.4 | 0.005 |

| 26–34 | 14.4 (13.7–15.1) | 15.8 (14.7–16.9) | 16.1 (15.2–17.0) | 16.4 (15.6–17.2) | 2.0 | 13.9 | <0.001 |

| 35–49 | 8.1 (7.5–8.8) | 8.9 (8.3–9.5) | 9.7 (9.0–10.4) | 9.9 (9.2–10.6) | 1.8 | 21.6 | <0.001 |

| 50–64 | 6.2 (5.4–7.1) | 6.6 (6.1–7.2) | 7.2 (6.4–8.0) | 7.0 (6.2–7.9) | 0.7 | 11.9 | 0.142 |

| ≥65 | 1.8 (1.4–2.4) | 2.4 (1.9–3.0) | 2.5 (1.9–3.3) | 2.8 (2.2–3.5) | 1.0 | 52.7 | 0.032 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 11.1 (10.7–11.5) | 11.6 (11.1–12.0) | 12.5 (12.0–13.0) | 12.6 (12.0–13.2) | 1.5 | 13.5 | <0.001 |

| Female | 6.9 (6.6–7.3) | 7.6 (7.2–8.0) | 7.7 (7.3–8.0) | 7.8 (7.3–8.2) | 0.8 | 11.8 | 0.005 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 9.2 (8.8–9.7) | 9.6 (9.2–10.0) | 10.2 (9.8–10.6) | 10.4 (9.9–10.8) | 1.2 | 12.6 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.1 (10.2–12.1) | 11.7 (10.9–12.5) | 12.3 (11.3–13.2) | 12.4 (11.4–13.5) | 1.3 | 11.7 | 0.049 |

| Hispanic | 7.3 (6.8–8.0) | 8.5 (7.8–9.2) | 8.8 (8.0–9.7) | 8.3 (7.8–8.9) | 1.0 | 13.4 | 0.015 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 6.9 (6.1–7.8) | 7.7 (6.8–8.7) | 7.7 (6.4–9.4) | 8.6 (7.3–10.2) | 1.7 | 25.1 | 0.040 |

| Education | |||||||

| High school or less | 9.4 (8.9–10.0) | 10.0 (9.5–10.4) | 10.5 (10.0–11.2) | 10.8 (10.3–11.4) | 1.4 | 14.6 | <0.001 |

| Some college | 11.6 (10.9–12.3) | 11.9 (11.3–12.7) | 12.6 (11.9–13.3) | 12.5 (11.9–13.1) | 0.9 | 7.8 | 0.032 |

| College degree or more | 6.5 (6.0–7.0) | 7.5 (6.8–8.3) | 7.9 (7.2–8.5) | 8.0 (7.4–8.6) | 1.5 | 23.2 | <0.001 |

| Reside in State Where Medical Cannabis Use is Legal | |||||||

| No | 7.1 (6.6–7.6) | 7.4 (7.1–7.7) | 7.7 (7.4–8.1) | 7.8 (7.4–8.2) | 0.7 | 10.0 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 10.3 (9.9–10.7) | 11.0 (10.6–11.5) | 11.6 (11.1–12.1) | 11.7 (11.2–12.2) | 1.4 | 13.6 | 0.019 |

| Prescribed Medical Cannabis in Past Year | |||||||

| No | 7.8 (7.5–8.1) | 8.1 (7.8–8.4) | 8.6 (8.3–8.9) | 8.7 (8.4–9.0) | 0.9 | 11.7 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 79.5 (75.1–83.2) | 81.6 (78.5–84.4) | 81.0 (78.1–83.6) | 82.4 (79.8–84.8) | 2.9 | 3.6 | 0.292 |

| Number of Days Used Cannabis in Past Year | |||||||

| 1–11 | 22.7 (20.8–24.8) | 26.0 (24.1–28.0) | 26.7 (24.7–28.9) | 24.4 (22.8–26.2) | 1.7 | 7.5 | 0.170 |

| 12–49 | 53.7 (50.8–56.6) | 57.6 (54.7–60.5) | 56.5 (53.4–59.5) | 57.4 (54.5–60.2) | 3.7 | 6.9 | 0.131 |

| 50–99 | 69.1 (65.3–72.7) | 67.8 (63.7–71.7) | 66.4 (62.3–70.3) | 70.6 (66.8–74.1) | 1.5 | 2.2 | 0.725 |

| 100–299 | 84.9 (82.8–86.8) | 84.4 (82.4–86.3) | 86.6 (84.9–88.2) | 85.4 (83.7–87.1) | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.336 |

| 300–365 | 98.6 (97.6–99.2) | 98.1 (97.3–98.6) | 98.6 (97.6–99.2) | 98.1 (97.2–98.7) | −0.5 | −0.5 | 0.554 |

| Past-Year Cannabis Use Disorder | |||||||

| No | 7.8 (7.5–8.1) | 8.4 (8.1–8.7) | 8.8 (8.5–9.1) | 8.9 (8.6–9.2) | 1.1 | 14.3 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 83.1 (80.2–85.7) | 85.1 (82.4–87.5) | 85.9 (83.0–88.4) | 85.5 (83.4–87.4) | 2.4 | 2.9 | 0.128 |

| Past-Year Blunt Use | |||||||

| No | 4.5 (4.3–4.8) | 4.9 (4.7–5.2) | 5.3 (5.1–5.6) | 5.2 (5.0–5.5) | 0.7 | 15.4 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 71.7 (70.3–73.1) | 74.4 (72.6–76.1) | 74.5 (73.2–75.8) | 75.0 (73.8–76.2) | 3.3 | 4.6 | 0.001 |

| Past-Year Other Drug Use | |||||||

| Tobacco | 21.4 (20.7–22.1) | 22.5 (21.6–23.4) | 23.8 (22.9–24.7) | 23.4 (22.6–24.2) | 2.0 | 9.3 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol | 12.2 (11.7–12.6) | 13.2 (12.8–13.7) | 13.8 (13.3–14.3) | 14.0 (13.4–14.5) | 1.8 | 14.8 | <0.001 |

| Cocaine | 64.7 (61.7–67.7) | 67.6 (63.5–71.5) | 65.4 (61.7–68.9) | 66.5 (63.0–69.8) | 1.8 | 2.8 | 0.683 |

| LSD | 77.6 (72.6–81.9) | 76.2 (71.6–80.3) | 82.4 (78.3–85.8) | 82.5 (78.8–85.7) | 4.9 | 6.3 | 0.026 |

| Ecstasy (MDMA/Molly) | 71.4 (66.8–75.6) | 75.1 (71.3–78.4) | 71.4 (67.7–74.9) | 73.6 (68.9–77.7) | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0.767 |

| Methamphetamine | 55.5 (47.4–63.3) | 52.5 (45.9–59.0) | 45.7 (39.0–52.6) | 56.7 (51.1–62.1) | 2.2 | 2.2 | 0.898 |

| Heroin | 58.8 (50.2–67.0) | 45.6 (37.4–53.9) | 48.2 (40.9–55.5) | 55.2 (44.9–65.1) | −3.6 | −6.1 | 0.897 |

| Prescription Opioids | 34.9 (32.5–37.3) | 32.5 (30.0–35.1) | 35.5 (33.4–37.7) | 37.0 (34.4–39.7) | 2.1 | 6.0 | 0.104 |

| Prescription Stimulants | 54.5 (51.3–57.6) | 49.0 (45.4–52.7) | 51.7 (48.9–54.4) | 51.3 (48.5–54.0) | −5.9 | −5.9 | 0.296 |

| Prescription Tranquilizers | 48.5 (45.6–51.3) | 43.0 (39.7–46.3) | 49.6 (46.2–53.0) | 47.6 (44.7–50.6) | −1.9 | −1.9 | 0.549 |

| Nicotine Dependence | 22.5 (20.8–24.4) | 22.9 (21.4–24.5) | 25.7 (24.0–27.5) | 25.5 (23.9–27.2) | 3.0 | 13.3 | 0.001 |

Aggregated data from the 2015–2019 US National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) among respondents ages ≥12 (n=282,768). Prescription opioids, stimulants, and tranquilizers refer to misuse. CI = confidence interval.

With respect to other drug use, those reporting past-year use of tobacco or alcohol were more likely to report cannabis use later in the year (Ps<0.001) and individuals who used LSD in particular had a 4.9% absolute increase in cannabis use (from 77.6% in Quarter 1 to 82.5% in Quarter 4, P=0.026). Those deemed to be dependent on nicotine were also more likely to report cannabis use later in the year with an absolute increase of 3.0% (from 22.5% to 25.5%; P=0.001). With respect to frequency of past-month use and past-month blunt use among those reporting past-month cannabis use (Table 3), those using on 1–2 days per month reported a lower prevalence later in the year (a 1.8% absolute decrease; P=0.046).

Table 3.

Quarterly Trends in Frequency of Past-Month Cannabis Use and Blunt Use Among Those Reporting Past-Month Cannabis Use, 2015–2019

| Weighted % (95% CI) | % Change from Quarter 1 to Quarter 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Quarter 1 (January-March) | Quarter 2 (April-June) | Quarter 3 (July-September) | Quarter 4 (October-December) | Absolute Change | Relative Change | Linear Trend P Value |

| Number of Days Used Cannabis in Past Month | |||||||

| 1–2 | 22.3 (20.9–23.9) | 22.3 (21.0–23.6) | 22.3 (21.0–23.7) | 20.5 (19.3–21.7) | −1.8 | −8.1 | 0.046 |

| 3–5 | 15.1 (13.9–16.5) | 15.7 (14.7–16.9) | 15.3 (14.2–16.6) | 15.8 (14.6–17.1) | 0.7 | 4.6 | 0.569 |

| 6–19 | 20.7 (19.2–22.3) | 20.3 (19.1–21.7) | 20.5 (19.3–21.7) | 20.3 (19.1–21.6) | −0.4 | −1.9 | 0.695 |

| 20–30 | 41.8 (40.1–43.5) | 41.6 (40.2–43.0) | 41.9 (39.9–43.9) | 43.5 (41.6–45.4) | 1.7 | 4.1 | 0.176 |

| Past-Month Blunt Use | |||||||

| No | 63.7 (62.4.65.0) | 63.5 (62.1–65.0) | 64.7 (63.3–66.1) | 64.1 (62.6–65.6) | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.435 |

| Yes | 36.3 (35.0–37.6) | 36.5 (35.0–37.9) | 35.3 (33.9–36.7) | 35.9 (34.4–37.4) | −0.4 | −1.1 | 0.435 |

Aggregated data from the 2015–2019 US National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) among respondents ages ≥12 reporting past-month cannabis use (n=34,370).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the seasonal nature of cannabis use among a nationally representative sample. We found that prevalence of cannabis use is consistently higher among those surveyed later in the year, peaking during the fourth quarter before dropping in the first quarter that follows, and that these quarterly increases are independent of increasing prevalence of use across years. This adds to a body of existing literature that has largely reported on higher rates of drug use during the summer months—a common time for outdoor social gatherings and breaks from work or school. Indeed, while our prevalence estimates in most years do demonstrate an upward spike around Quarter 2 through Quarter 3 (corresponding to summer months), the peaks in cannabis use that occur later on in the year and the consistent dips in Quarter 1 are novel findings.

At least to some extent, the increased usage rates heading into the summer months may be related to use of other drugs as well. For example, we found that the largest absolute increase in cannabis use was observed among those reporting past-year LSD use, which itself is known to be more prevalent in summer months (Palamar et al., 2019). Use of psychedelics such as LSD are especially common among young people during summer months due to, at least in part, the increasing popularity of large dance festivals, so increases in cannabis use during these months may indicate higher prevalence of use in party or recreational settings. However, our findings also show that use increased among those reporting alcohol and/or nicotine use, and particularly among those who were nicotine dependent. Akin to the patterns of LSD use, alcohol use follows a pattern whereby use, frequent use, and heavy use are lowest earlier in the calendar year and highest in summer months (Knudsen and Skogen, 2015). In addition to previous findings, however, we reiterate that our study detected a continued increase in prevalence of cannabis use after the summer months before dipping into the next year. With respect to potential supply-sided factors, the consistent dip in cannabis use during winter months may be attributable to lower yields of cannabis harvest (Headset Cannabis Market Reports, 2019), while colder weather conditions may also diminish demand for cannabis, which is presumably commonly consumed outdoors. Additional factors may be fewer days in February and quitting related to New Year’s resolutions.

It may be prudent for public health officials and clinicians to be mindful of the increased prevalence of cannabis use throughout the year as well as the potential capacity for increasing co-use of other drugs. In Europe, there have been clear seasonal variations in drug-related emergency room visits with most occurring in June through August (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2016), and research has long established the potential dangers of polydrug use (McCabe et al., 2006; Palamar et al., 2019). Similarly, increased use of cannabis towards the end of the year, perhaps during holidays such as Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Hanukkah, may be an area for potential concern if usage rates of other drugs also peak during this period. Wastewater analyses conducted in Croatia, for example, have found that cocaine, amphetamine, and ecstasy increase in December around Christmas and New Year’s Eve (Krizman-Matasic et al., 2019), so additional research on the seasonality of other substances is certainly welcome.

While studies focusing on drug initiation report that first use usually occurs during summer months (CBHSQ, 2012), our findings further add that prevalence of past-month cannabis use continues to increase throughout the year. Moreover, our results suggest that increases in use may be more recreational in nature as opposed to medical or chronic use. One indication is that similar small increases occurred among both those residing inside and outside of states with legal medical cannabis. Similarly, increases occurred among those not prescribed cannabis in the past year and those not proxy-diagnosed with CAD. However, on the contrary, those who smoked blunts in the past year reported increased cannabis use later in the year (although we did not find that current blunt use shifts across quarters among past-month cannabis users). Blunt use is often associated with more chronic use as blunts typically contain more cannabis than joints with use leading to greater levels of intoxication and withdrawal, placing people at higher risk for CAD (Mariani et al., 2011; Ream et al., 2008; Timberlake, 2009).

Although past-month drug use is believed to be relatively stable across the year (SAMHSA, 2012), we determined that this is not the case with respect to cannabis. We believe this has implications not only for NSDUH but for other studies that estimate cannabis use. NSDUH, like other national surveys, reports estimates based on aggregated data collection throughout the year so potential differences likely balance out. However, when a study is conducted during a specific time of year (e.g., school-based surveys), estimates will likely be affected.

Ultimately, we hope that these findings can be utilized by epidemiologists and clinicians alike in order to efficiently allocate their efforts and resources. For example, as public health surveillance of cannabis use will inevitably continue, given the rise in popularity of cannabis, consideration must be given to the fact that surveys administered at the end of the year may yield significantly different prevalence estimates than at the beginning of the year. Similarly, accounting for the high prevalence of cannabis use during the summer months and later in the year, and peak usage rates of other substances such as LSD and alcohol, may be a prudent endeavor for drug prevention efforts. For clinicians and other healthcare workers who treat patients, the seasonal nature of cannabis use can allow them to anticipate and prepare for interactions with cannabis users accordingly.

4.1. Limitations

This study was limited by an inability to account for specific state-level marijuana laws. Additionally, participants were not specifically asked about vaping or dabbing of cannabis, so it is possible that some individuals who only vape or dab underreported use. Quarters represent when the interview was conducted and not necessarily when use occurred; therefore, use could have occurred near the end of the previous quarter. The majority of interviews are typically conducted within the first half of a quarter (SAMHSA, 2012) and this can positively skew the distribution of interviews with past-month use occurring near the cutoff between quarters. This means that use in late June, for example, could be coded as occurring in Quarter 3 (July through September). Data collection during Quarters 1 and 4 may also be shorter than in other quarters due to interviewer trainings and holidays, respectively (CBHSQ, 2019). To our knowledge, NSDUH did not adjust weights based on potential skewed distributions within quarters. Finally, given that NSDUH was redesigned with an edited survey administered beginning in 2015 (SAMHSA, 2015), trends for some variables of interest were broken and we could not thus include earlier years in our analyses.

4.2. Conclusions

We detected seasonal variation in cannabis use in the US and this variation was independent of increasing prevalence of use across years. Researchers should consider seasonal variation when examining trends in cannabis use. This knowledge can also aid clinicians in preparing measures for timely screening and counseling of patients on potential health risks and benefits.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Past-month cannabis use increases throughout the year independent of annual increases

Quarterly increases peak in the fourth quarter and drop in the following first quarter

Recreational use, rather than medical or chronic use, appear to drive these shifts

People who use other drugs in particular increase use—especially those who use LSD

Researchers estimating prevalence of cannabis use should consider seasonal effects

Acknowledgments

J. Palamar and B. Han are funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01DA044207, PI: Palamar, and K23DA043651, PI: Han)

Role of funding source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01DA044207 and K23DA043651. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Borsari B, Short EE, Mastroleo NR, Hustad JT, Tevyaw TO, Barnett NP, Kahler CW, Monti PM, 2014. Phone-delivered brief motivational interventions for mandated college students delivered during the summer months. J Subst Abuse Treat. 46, 592–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Kotz D, Michie S, Stapleton J, Walmsley M, West R, 2014. How effective and cost-effective was the national mass media smoking cessation campaign ‘Stoptober’? Drug Alcohol Depend. 135, 52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2012. The NSDUH Report: Monthly Variation in Substance Use Initiation among Adolescents. (Accessed 23 November 2020) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; (Accessed 23 November 2020) https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/nsduh-report-monthly-variation-substance-use-initiation-among-adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2019. Section 2: Sample Design Report In 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Methodological Resource Book. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; (Accessed 23 November 2020) https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsqreports/NSDUHmrbSampleDesign2018/NSDUHmrbSampleDesign2018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cerda M, Mauro C, Hamilton A, Levy NS, Santaella-Tenorio J, Hasin D, et al. , 2019. Association between recreational marijuana legalization in the United States and changes in marijuana use and cannabis use disorder from 2008 to 2016. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 165–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin D, 2012. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 120, 22–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Gitchell JG, Shiffman S, 2011. Seasonality in sales of nicotine replacement therapies: patterns and implications for tobacco control. Nicotine Tob. Res. 13, 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2016. Hospital emergency presentations and acute drug toxicity in Europe: update from the Euro-DEN Plus research group and the EMCDDA. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; (Accessed 23 November 2020) https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/2973/TD0216713ENN-1_Final%20pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Gmel G, Estévez N, Bähler C, Mohler-Kuo M, 2015. Temporal patterns of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related road accidents in young Swiss men: seasonal, weekday and public holiday effects, 2015. Alcohol Alcohol. 50, 565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BH, Palamar JJ, 2020. Trends in cannabis use among older adults in the United States, 2015–2018. JAMA Intern. Med. 180, 609–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Stohl M, Galea S, et al. , 2017. US adult illicit cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and medical marijuana laws: 1991–1992 to 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 579–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headset Cannabis Market Reports, 2019. Understanding Seasonality in Cannabis Sales. (Accessed 23 November 2020) https://www.headset.io/industry-reports/understanding-seasonality-in-cannabis-sales.

- Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA, 2010. Applied Survey Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen AK, Skogen JC, 2015. Monthly variations in self-report of time-specified and typical alcohol use: the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT3). BMC Public Health 15, 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizman-Matasic I, Senta I, Kostanjevecki P, Ahel M, Terzic S, 2019. Long-term monitoring of drug consumption patterns in a large-sized European city using wastewater-based epidemiology: comparison of two sampling schemes for the assessment of multiannual trends. Sci. Total Environ. 647, 474–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN, 2015. Monthly variation in substance use initiation among full-time college students In The CBHSQ Report (pp. 1–14). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; (Accessed 23 November 2020) https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2049/ShortReport-2049.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani JJ, Brooks D, Haney M, Levin FR, 2011. Quantification and comparison of marijuana smoking practices: blunts, joints, and pipes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 113, 249–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Morales M, Young A, 2006. Simultaneous and concurrent polydrug use of alcohol and prescription drugs: prevalence, correlates, and consequences. J. Stud. Alcohol 67, 529–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, 2020. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research; (Accessed 23 November 23, 2020) http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol1_2019.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Merrill JE, Yurasek AM, Mastroleo NR, Borsari B, 2016. Summer versus school-year alcohol use among mandated college students, 2016. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 77, 51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momperousse D, Delnevo CD, Lewis MJ, 2007. Exploring the seasonality of cigarette-smoking behaviour. Tobacco Control 16, 69–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Acosta P, Le A, Cleland CM, Nelson LS, 2019. Adverse drug-related effects among electronic dance music party attendees. Int. J. Drug Policy 73, 81–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Rutherford C, Keyes KM, 2019. Summer as a risk factor for drug initiation. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 947–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philbin MM, Mauro PM, Greene ER, Martins SS, 2019. State-level marijuana policies and marijuana use and marijuana use disorder among a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States, 2015–2017: sexual identity and gender matter. Drug Alcohol Depend. 204, 107506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream GL, Benoit E, Johnson BD, Dunlap E, 2008. Smoking tobacco along with marijuana increases symptoms of cannabis dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 95, 199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp, 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015. National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2014 and 2015 Redesign Changes. Rockville, MD: (Accessed 23 November 2020) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519778/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: (Accessed 23 November 2020) https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012. CBHSQ Methodology Report In National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Sample Redesign Issues and Methodological Studies. Rockville, MD: (Accessed 23 November 2020) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531540/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauras JA, Chaloupka FJ, Emery S, 2005. The impact of advertising on nicotine replacement therapy demand. Soc Sci Med. 60, 2351–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake DS, 2009. A comparison of drug use and dependence between blunt smokers and other cannabis users. Subst. Use Misuse 44, 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuizen S, Zawertailo L, Ivanova A, Hussain S, Selby P, 2020. Seasonal variation in demand for smoking cessation treatment and clinical outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.