Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Animal and observational studies indicate that smoking is a risk factor for aneurysm formation and rupture, leading to non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). However, a definitive causal relationship between smoking and the risk of SAH has not been established. Using Mendelian Randomization analyses, we tested the hypothesis that smoking is causally linked to the risk of SAH.

Methods:

We conducted a one-sample Mendelian Randomization (MR) study using data from the UK Biobank, a large cohort study that enrolled over 500,000 Britons aged 40-69 from 2006 to 2010. Participants of European descent were included. SAH cases were ascertained using a combination of self-reported, electronic medical record, and death registry data. As the instrument, we built a polygenic risk score (PRS) using independent genetic variants known to associate (p<5x10−8) with smoking behavior. This PRS represents the genetic susceptibility to smoking initiation. The primary MR analysis utilized the ratio method. Secondary MR analyses included the inverse variance weighted (IVW) and weighed median (WM) methods.

Results:

A total of 408,609 study participants were evaluated (mean age 57 [SD 8], female sex 220,937 [54%]). Among these, 132,566 (32%) ever smoked regularly and 904 (0.22%) had a SAH. Each additional standard deviation of the smoking PRS was associated with 21% increased risk of smoking (OR 1.21, 95%CI 1.20-1.21; p<0.001) and a 10% increased risk of SAH (OR 1.10, 95%CI 1.03-1.17; p=0.006). In the primary MR analysis, genetic susceptibility to smoking was associated with a 63% increase in the risk of SAH (OR 1.63, 95%CI 1.15-2.31; p=0.006). Secondary analyses using the IVW method (OR 1.57, 95%CI 1.13-2.17; p=0.007) and the WM method (OR 1.74, 95%CI 1.06-2.86; p=0.03) yielded similar results. There was no significant pleiotropy (MR-Egger intercept p=0.39; MR-PRESSO global test p=0.69).

Conclusions:

These findings provide evidence for a causal link between smoking and the risk of SAH.

Keywords: Hemorrhagic Stroke, Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, Intracranial Aneurysm, Mendelian Randomization, Genetic Variation, Genetics, Cerebral Aneurysm, Intracranial Hemorrhage

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is an uncommon subtype of stroke that carries high morbidity and mortality. SAH affects mainly middle-aged individuals, leading to substantial morbidity in persons with long survival1. Smoking is a well-known risk factor for multiple cardiovascular conditions. Several observational studies have shown that smoking is associated with an increased risk of SAH2–4, with stronger associations observed for women5. However, a definitive causal relationship between smoking and SAH risk is difficult to establish as it would be unethical to perform clinical trials utilizing a harmful intervention such as smoking.

Population genetics offers powerful tools to evaluate causality for non-genetic exposures6. Genetic variants known to be strongly associated with smoking behavior can be used as instruments in Mendelian Randomization analyses to evaluate the causal relationship between smoking and risk of SAH. These genetic variants are randomly distributed during meiosis and are therefore relatively immune to confounding by environmental factors. A previous study has shown a causal relationship between smoking and ischemic stroke using this approach7 but, to date, similar studies have not been pursued for SAH. We therefore conducted a Mendelian Randomization (MR) study to test the hypothesis that smoking is causally linked to an increased risk of SAH.

METHODS

Data availability

Data from the UK Biobank is publicly available upon request.

Study design

The UK Biobank is a large cohort study that enrolled over 500,000 persons aged 40-69 years from across the UK. It ascertained numerous population characteristics and collected biological samples and genetic information8. This large prospective study received approval by the appropriate institutional review board. All participants provided informed consent. For this study, we included participants from genetically-confirmed European ancestry only.

Outcome data

First-ever SAH cases were ascertained using the algorithmically-defined outcomes available at the UK Biobank. This ascertainment process combines data from (1) the baseline interview conducted when study participants were enrolled in the study, (2) nation-wide monitoring systems (Hospital Episode Statistics [England], Scottish Morbidity Records [Scotland], and Patient Episode Database [Wales]) that capture data from all admissions, before and after enrollment in the study; and (3) and death register data. The last two data sources use International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes to capture information on specific conditions. For SAH, the ICD-9 code 430.X and the ICD-10 160.X were used. To avoid misclassification that could lead to bias, we only used SAH events with an associated hospital admission.

Genetic data

UK Biobank participants were genotyped using UK Biobank Axiom Array. Standard quality control procedures were performed centrally by the UK Biobank research team, as previously reported. Imputation was also performed centrally, using a reference panel composed by the UK10K haplotype9 and 1000 Genomes Phase 310 reference panels11, and the same algorithm implemented by the IMPUTE2 program12. We implemented post-imputation quality control filters, including minor allele frequency <1% and information score <0.7 and used principal component analysis to account for population structure.

Instrumental variable

MR analysis constitutes a special case of instrumental variable analysis. For this study, the instrument was a polygenic risk score (PRS) that represents the genetic propensity to smoke. A recent genome-wide association meta-analysis of 1.2 million persons identified several independent single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with smoking initiation (defined as an individual ever smoking regularly)13. We used summary statistics from this study to build a smoking-related PRS using independent (r2 < 0.1) SNPs known to be associated with smoking initiation at genome-wide levels (p<5x10−8). All selected SNPs were aligned to the GRCh37 assembly of the human genome. To assure common directionality of effects, for each SNP the allele associated with an increase in propensity to smoke was identified and utilized as the tested allele in down-stream analyses. The PRS for each individual is the sum of the product of the risk allele counts for each locus multiplied by the allele’s reported effect on the propensity to smoke.

Statistical analysis

We present discrete variables as counts (percentage [%]) and continuous variables as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]), as appropriate.

Non-genetic observational analysis.

We fitted bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models to assess the relationship between smoking initiation (i.e. ever smoking regularly) and risk of SAH. We also conducted bivariate and multivariable regression analysis modeling the exposure as an ordinal variable defined by pack/years of smoking (0, 0.05-20, 20-40 and >40). Multivariable models included age, sex, and hypertension as covariates.

Polygenic risk score analysis.

Using individual level genetic data, we fitted multivariable logistic regression models to assess the relationship between the smoking-related PRS and both smoking initiation and SAH risk, adjusting for age, sex, and the first four genetic principal components. These association tests determine the risk of smoking initiation and the risk of SAH, respectively, associated with an increase of one standard deviation in the PRS.

Primary MR analysis.

We used the betas of the association tests between the smoking-related PRS and risk of smoking initiation and SAH to perform the MR ratio method.

Secondary MR analyses.

Using summary statistics for each SNP included in the instrument, we implemented the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) and weighted median (WM) MR methods. These summary statistics were obtained by testing for associations between each SNP and both smoking initiation and SAH risk within the UK Biobank, adjusting for age, sex and the first four genetic principal components.

Pleiotropy.

Given the possibility that genetic variants influence the risk of SAH through pathways other than the exposure of interest (horizontal pleiotropy), we conducted pleiotropy analysis to identify and account for this potential bias. Using the same summary statistics, we implemented the MR-Egger14 and Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO)15 approaches to evaluate the presence of horizontal pleiotropy.

Stratified analyses.

Because sex and hypertension2–5 are well-known risk factors for SAH, we implemented stratified analyses by these variables and tested for interaction between these risk factors and the smoking-related PRS by adding product terms to the regression models.

Software.

We used PLINK16 to conduct quality control procedures, PRS analysis and single-SNP association testing, and the MendelianRandomization and MR-PRESSO packages in R 3.6 to complete MR analyses. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for the single test utilized to evaluate the primary hypothesis that genetic propensity to smoke increases the risk of SAH.

RESULTS

Of the 502,536 study participants enrolled in the UK Biobank, we excluded those who were not from European ancestry (n=92,907), had low quality genetic information based on standard quality control parameters (n=2,012) or withdrew consent (n=48). Our final sample included a total of 408,609 persons (mean age at recruitment 57 years [SD 8], female sex 220,937 [54%]). Baseline features are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Overall (n=408,609) | Controls (n=407,705) | SAH (n=904) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 56.9 (8.0) | 56.9 (8.0) | 57.87 (7.29) | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 187,672 (45.9) | 187,336 (45.9) | 336 (37.2) | <0.001 |

| Ever smoked, n (%) | 132,566 (32.4) | 132,154 (32.4) | 412 (45.6) | <0.001 |

| Smoking p/y, mean (SD) | 7.2 (15.0) | 7.2 (15.0) | 12.12 (19.24) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 108,595 (26.6) | 108,265 (26.6) | 330 (36.5) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 50,469 (12.4) | 50,340 (12.3) | 129 (14.3) | 0.088 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 19,245 (4.7) | 19,208 (4.7) | 37 (4.1) | 0.425 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 3,174 (0.8) | 3,165 (0.8) | 9 (1.0) | 0.575 |

Abbreviations: SAH=Subarachnoid hemorrhage. SD=Standard deviation. p/y= Pack/years.

Smoking and non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage in the UK Biobank

In line with prior studies, we found a strong association between smoking and risk of SAH. Of the 408,609 study participants included in the analysis, 132,566 (32%) ever smoked regularly and 904 (0.22%) had SAH. In bivariate analysis, smoking initiation was associated with a 75% increased risk of SAH (OR 1.75, 95%CI 1.53-1.99; p<0.001). In multivariable analysis adjusting by sex, age and hypertension, smoking initiation was associated with a 78% increased risk of SAH (OR 1.78, 95%CI 1.56-2.03; p<0.001). The relationship between smoking and SAH risk appeared to be linear according to pack/years of smoking, ranging from a 27% increased risk in those 0.05-20 pack/years to 2.5-fold increased risk in those smoking >40 pack/years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Observational, non-genetic association between smoking and risk of SAH.

| Exposure | Risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P Value | OR (95%CI) | P Value | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoked | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Former smoker | 1.49 (1.28-1.72) | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.27-1.71) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 2.60 (2.17-3.11) | <0.001 | 2.80 (2.33-3.35) | <0.001 |

| Lifelong exposure | ||||

| 0 p/y | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| 0.05 – 20 p/y | 1.25 (1.03-1.49) | 0.02 | 1.27 (1.05-1.52) | 0.01 |

| 20 – 40 p/y | 2.02 (1.68-2.41) | <0.001 | 2.03 (1.69-2.44) | <0.001 |

| >40 p/y | 2.51 (1.99-3.13) | <0.001 | 2.58 (2.04-3.24) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: OR=Odds ratio. 95%C= 95% Confidence interval. p/y=Pack/years.

Genetic susceptibility to smoke

Genetic susceptibility to smoking was strongly associated with both smoking initiation and risk of SAH. The smoking-related PRS included 126 SNPs (Supplementary Table I). The mean minor allele frequency across all SNPs was 31% (SD 13%), including 5 (4%) low-frequency variants (i.e. those with a minor allele frequency <5%). Each additional standard deviation of this smoking PRS was associated with a 21% increased risk of smoking initiation in the UK Biobank population (OR 1.21, 95%CI 1.20-1.21; p<0.001). Similarly, each additional standard deviation of the smoking PRS was associated with a 10% increased risk of SAH (OR 1.10, 95%CI 1.03-1.17; p=0.006).

Mendelian Randomization analysis of smoking and the risk of SAH

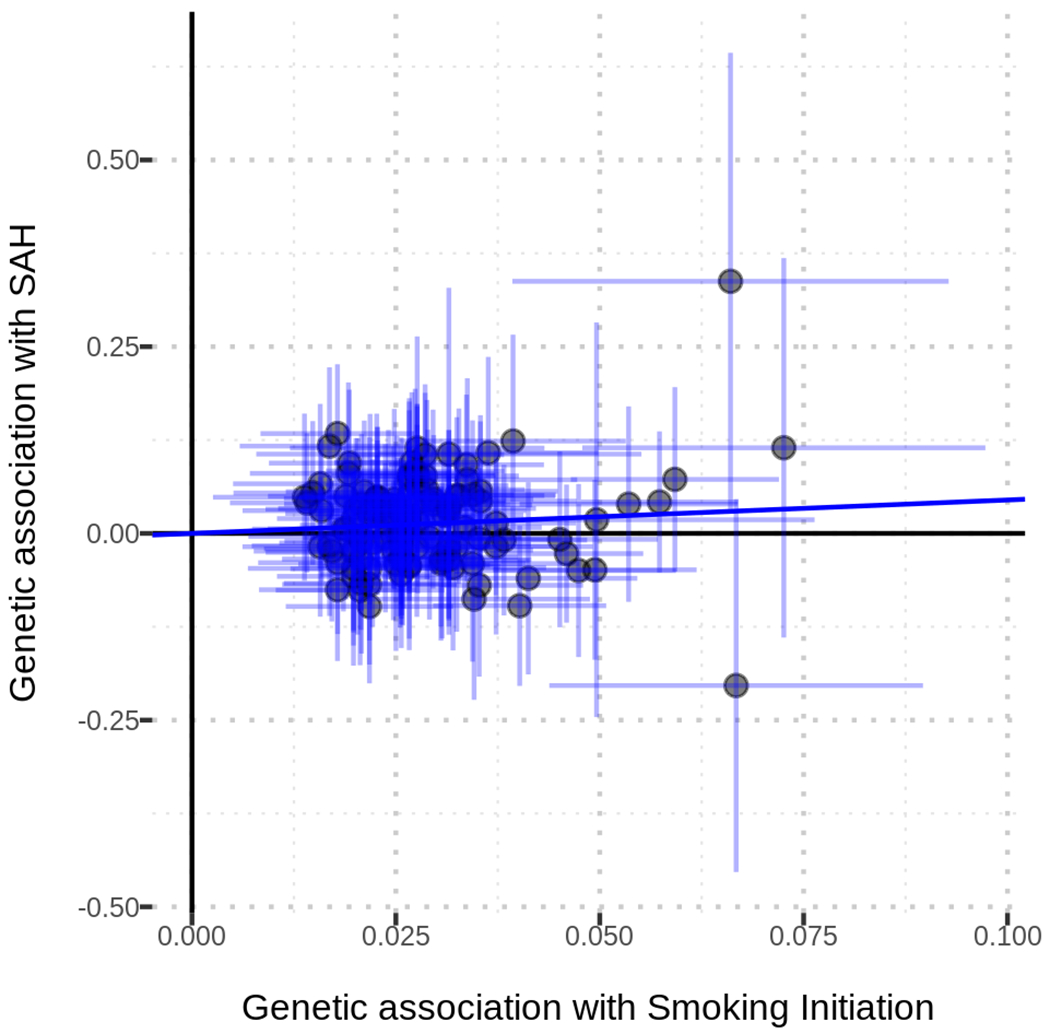

In the primary analysis utilizing the ratio method, genetic susceptibility to smoking was associated with a 63% increase in risk of SAH (OR 1.63, 95%CI 1.15-2.31; p=0.006). Secondary analyses using the IVW method (OR 1.57, 95%CI 1.13-2.17; p=0.007) and the WM method (OR 1.74, 95%CI 1.06-2.86; p=0.03) yielded comparable results. There was no significant horizontal pleiotropy (Table 3), as evaluated by both the MR-Egger intercept (p=0.39) and the MR-PRESSO global test (p=0.69) (Figure 1). MR analyses stratified by pack/years confirmed the association between genetic susceptibility to smoking and SAH risk across all evaluated strata but did not yield the linear relationship observed in the epidemiologic part of our analysis. Compared to never smokers, the MR results were similar for those who smoked 0.05-20 pack/years (OR 1.63, 95%CI 1.01-2.62; p=0.04), 20-40 pack/years (OR 1.65, 95%CI 1.13-2.41; p=0.009) and >40 pack/years (OR 1.56, 95%CI 1.08-2.25; p=0.02).

Table 3.

Mendelian Randomization results.

| Mendelian Randomization Method | Data type | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association tests | |||

| Ratio Method | Individual level data | 1.63 (1.15 - 2.31) | 0.006 |

| Inverse variance weighted | Summary statistics | 1.57 (1.13 - 2.17) | 0.007 |

| Weighted Median | Summary statistics | 1.74 (1.06 - 2.86) | 0.028 |

| MR-PRESSO | Summary statistics | 1.56 (1.14 - 2.15) | 0.006 |

| Pleiotropy tests | |||

| MR-Egger intercept | Summary statistics | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | 0.39 |

| MR-PRESSO Global Test | Summary statistics | - | 0.69 |

Abbreviations: MR=Mendelian Randomization. OR= Odds ratio. PRS=Polygenic risk score. IVW=Inverse variance weighted. MR-Egger=Mendelian Randomization using Egger regression. MR-PRESSO= Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier.

Figure 1. Mendelian Randomization plot.

The plot presents the effect estimates of association tests between the SNPs included in the instrument and smoking initiation (X axis) and risk of SAH (Y axis).

Stratification by sex and hypertension

In stratified analyses (Table 4), the point estimate for the association between the smoking PRS and SAH risk was higher and significant in women (OR 1.14, 95%CI 1.05-1.24) compared to men (OR 1.02; 95%CI 0.92-1.14). Similarly, the point estimate for the association between smoking PRS and SAH risk was higher and significant for hypertensives (OR 1.12, 95%CI 1.01-1.25) compared to normotensives (OR 1.07, 95%CI 0.99-1.17). We obtained similar results when conducting stratified MR analyses (Table 4). Despite these results, neither the formal test for interaction for sex (interaction p=0.22) nor the one for hypertension (interaction p=0.49) was statistically significant.

Table 4.

Stratified analyses by sex and hypertension.

| Stratification variable | Polygenic Risk Score Analysis | Mendelian Randomization Analysis | Interaction p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.14 (1.04-1.24) | 1.99 (1.29-3.08) | 0.22 |

| Male | 1.02 (0.92-1.14) | 1.14 (0.64-2.02) | |

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes | 1.12 (1.01-1.25) | 2.04 (1.06-3.95) | 0.49 |

| No | 1.07 (0.99-1.17) | 1.45 (0.95-2.21) |

Abbreviations: OR= Odds ratio. 95%CI= 95% Confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

We found that a stronger genetic predisposition to smoking is significantly associated with an increased risk of SAH and that this association might be stronger in women and persons with hypertension. These findings provide important evidence to support a causal relationship between smoking and SAH.

Observational evidence has consistently shown a robust and dose-dependent relationship between smoking and the risk of SAH2,3,5,17–19. Smoking cessation, on the other hand, appears to decrease the risk of SAH, but some degree of the attributable risk may be irreversible, especially in former heavy smokers20,21. Moreover, laboratory and experimental studies in animal propose oxidative stress and inflammation as the mediating mechanisms behind this link22,23. In line with these studies, epidemiological work has found that the incidence in SAH is currently decreasing in parallel with decreases in the smoking rate24–26. In our study, we found a robust association between smoking and risk of SAH with a clear dose-response relationship that ranged from 27% increase in SAH risk in those smoking less than <20 p/y to almost a three-fold increase in those smoking more than 40 p/y. This recapitulation of known smoking-SAH associations in our study population constituted a necessary condition to conduct genetic analysis aimed at evaluating the casual association between genetically-determined smoking and risk of SAH.

However, deriving causality from the observational evidence outlined above is problematic due to the possibility of bias introduced by confounding factors. Addressing this question through experimental studies in humans (i.e. randomized clinical trials) would be unethical given the known harms produced by smoking. Population genetics provides powerful tools to overcome these limitations in causal inference. Genetic variants known to associate with smoking can be used as instruments in Mendelian Randomization analyses aimed to evaluate this causal relationship, as these variants are randomly distributed during meiosis and ought to be exempt from confounding by environmental exposures. Using this approach, we found that genetic susceptibility to smoking initiation was associated with a 60% increase in the risk of SAH. Importantly, sensitivity analyses using more conservative methods aimed to decrease the possibility of horizontal pleiotropy yielded similar results. While the interaction analyses between the genetic susceptibility to smoking initiation and sex and hypertension, two other important determinants of SAH, were not statistically significant, the higher point estimates for these associations in women and hypertensives point to an important future direction of research.

The most important strengths of our study are its large sample size and the availability of individual-level genetic data from all study participants. In terms of limitations, the utilization of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes to ascertain SAH cases in the UK Biobank may have introduced some misclassification of the outcome. However, while certainly limited in its ability to fully capture the diagnostic nuances of SAH cases, the ICD system does have appropriate codes to differentiate traumatic and non-traumatic SAH (we used the latter). In addition, even if present, the aforementioned misclassification is likely randomly distributed across levels of the exposure, thus introducing bias towards the null. A second important limitation is the absence of an independent dataset to replicate the presented results. The relatively low incidence of SAH in Western populations limits the amount of cases with available genetic data. Nevertheless, because this study was not intended at risk loci discovery, it could be argued that independent replication for this specific analysis is not strictly needed. Another important limitation is that our study was limited to genetically-determined Caucasians. As a result, our results cannot be immediately extrapolated to other racial/ethnic populations. Because of the disproportion of available genetic data in whites versus other race/ethnic groups is becoming a serious barrier to conduct genetic studies in non-whites persons, this particular limitation should be addressed soon by follow-up studies.

SAH is an uncommon disease with a limited number of studies with available genetic information. As a result, international collaborations will be fundamental to replicate, externally validate and extend the results of our study. In addition, these large data resources would provide the ideal framework to evaluate whether our results can be used to develop precision medicine approaches aimed at detecting persons at high risk of intracranial aneurysms. This is an appealing research avenue, as genetic information could identify persons that may benefit from early screening with vessel imaging studies, like computed tomography or magnetic resonance angiography.

Conclusion

We used Mendelian Randomization analyses to evaluate whether genetic predisposition to smoking initiation is causally related to the risk of SAH in a large population of British persons. We found that a stronger genetic predisposition to smoking is significantly associated with an increased risk of SAH. These findings provide important evidence to support a causal relationship between smoking and the risk of SAH.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SOURCES OF FUNDING

GJF is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K76AG59992), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R03NS112859), the American Heart Association (18IDDG34280056), a Yale Pepper Scholar Award (P30AG021342), and the Neurocritical Care Society Research Fellowship. TMG is supported by the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG21342) and an Academic Leadership Award (K07AG043587) from the National Institute on Aging. KNS is supported by the NIH (U24NS107136, U24NS107215, R01NR018335, R01NS107215, U01NS106513, R03NS112859) and the American Heart Association (18TPA34170180, 17CSA33550004).

DISCLOSURES

KNS reports grants from Hyperfine, grants from Bard, grants from Biogen, grants from Novartis, consultant pay from Ceribell, personal fees from Zoll and equity from Alva outside the submitted work. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- SAH

Non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage

- MR

Mendelian Randomization

- PRS

Polygenic Risk Score

- SNP

Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism

- IVW

Inverse Variance Weighted

- WM

Weighted Median

- MR-PRESSO

Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier

- P/Y

Smoking pack/years

Footnotes

Twitter handles: @GuidoFalconeMD, @jn_acosta, @NeurologyYale, @YaleNeuroICU

REFERENCES

- 1.Macdonald RL, Schweizer TA. Spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet [Internet] 2017;389:655–666. Available from: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30668-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonita R Cigarette smoking, hypertension and the risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage: A population-based case-control study. Stroke. 1986;17:831–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juvela S, Hillbom M, Numminen H, Koskinen P. Cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption as risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1993;24:639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller TB, Vik A, Romundstad PR, Sandvei MS. Risk factors for unruptured intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid hemorrhage in a prospective population-based study. Stroke. 2019;50:2952–2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindbohm JV, Kaprio J, Jousilahti P, Salomaa V, Korja M. Sex, Smoking, and Risk for Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2016;47:1975–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grover S, Del Greco FM, Stein CM, Ziegler A. Mendelian randomization. Methods Mol. Biol 2017;1666:581–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsson SC, Burgess S, Michaëlsson K. Smoking and stroke: A mendelian randomization study. Ann. Neurol 2019;86:468–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, Motyer A, Vukcevic D, Delaneau O, O’Connell J, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562:203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang J, Howie B, McCarthy S, Memari Y, Walter K, Min JL, Danecek P, Malerba G, Trabetti E, Zheng HF, et al. Improved imputation of low-frequency and rare variants using the UK10K haplotype reference panel. Nat. Commun 2015;6:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altshuler DL, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, Chakravarti A, Clark AG, Collins FS, De La Vega FM, Donnelly P, Egholm M, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou WC, Zheng HF, Cheng CH, Yan H, Wang L, Han F, Richards JB, Karasik D, Kiel DP, Hsu YH. A combined reference panel from the 1000 Genomes and UK10K projects improved rare variant imputation in European and Chinese samples. Sci. Rep 2016;6:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Leeuwen EM, Kanterakis A, Deelen P, Kattenberg MV, Slagboom PE, De Bakker PIW, Wijmenga C, Swertz MA, Boomsma DI, Van Duijn CM, et al. Population-specific genotype imputations using minimac or IMPUTE2. Nat. Protoc 2015;10:1285–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, Li Y, Brazel DM, Chen F, Datta G, Davila-Velderrain J, McGuire D, Tian C, et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat. Genet 2019;51:237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur. J. Epidemiol 2017;32:377–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet [Internet] 2018;50:693–698. Available from: 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LCAM, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: Rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreasen TH, Bartek J, Andresen M, Springborg JB, Romner B. Modifiable risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2013;44:3607–3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng X, Qian Z, Zhang B, Guo E, Wang L, Liu P, Wen X, Xu W, Jiang C, Li Y, et al. Number of cigarettes smoked per day, smoking index, and intracranial aneurysm rupture: A case-control study. Front. Neurol 2018;9:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korja M, Lehto H, Juvela S. Lifelong rupture risk of intracranial aneurysms depends on risk factors: A prospective Finnish cohort study. Stroke. 2014;45:1958–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Can A, Castro VM, Ozdemir YH, Dagen S, Yu S, Dligach D, Finan S, Gainer V, Shadick NA, Murphy S, et al. Association of intracranial aneurysm rupture with smoking duration, intensity, and cessation. Neurology [Internet] 2017. [cited 2020 Feb 11];89:1408–1415. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28855408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim CK, Kim BJ, Ryu WS, Lee SH, Yoon BW. Impact of smoking cessation on the risk of subarachnoid haemorrhage: A nationwide multicentre case control study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2012;83:1100–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starke RM, Thompson JW, Ali MS, Pascale CL, Lege AM, Ding D, Chalouhi N, Hasan DM, Jabbour P, Owens GK, et al. Cigarette smoke initiates oxidative stress-induced cellular phenotypic modulation leading to cerebral aneurysm pathogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 2018;38:610–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalouhi N, Ali MS, Starke RM, Jabbour PM, Tjoumakaris SI, Gonzalez LF, Rosenwasser RH, Koch WJ, Dumont AS. Cigarette smoke and inflammation: Role in cerebral aneurysm formation and rupture. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korja M, Lehto H, Juvela S, Kaprio J. Incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage is decreasing together with decreasing smoking rates. Neurology. 2016;87:1118–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicholson P, Ohare A, Power S, Looby S, Javadpour M, Thornton J, Brennan P. Decreasing incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurointerv. Surg 2019;11:320–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etminan N, Chang HS, Hackenberg K, De Rooij NK, Vergouwen MDI, Rinkel GJE, Algra A. Worldwide Incidence of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage According to Region, Time Period, Blood Pressure, and Smoking Prevalence in the Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:588–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from the UK Biobank is publicly available upon request.