Abstract

Objective

To analyse how non-adherence to prescribed treatments might be prevented, screened, assessed and managed in people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs).

Methods

An overview of systematic reviews (SR) was performed in four bibliographic databases. Research questions focused on: (1) effective interventions or strategies, (2) associated factors, (3) impact of shared decision making and effective communication, (4) practical things to prevent non-adherence, (5) effect of non-adherence on outcome, (6) screening and assessment tools and (7) responsible healthcare providers. The methodological quality of the reviews was assessed using AMSTAR-2. The qualitative synthesis focused on results and on the level of evidence attained from the studies included in the reviews.

Results

After reviewing 9908 titles, the overview included 38 SR on medication, 29 on non-pharmacological interventions and 28 on assessment. Content and quality of the included SR was very heterogeneous. The number of factors that may influence adherence exceed 700. Among 53 intervention studies, 54.7% showed a small statistically significant effect on adherence, and all three multicomponent interventions, including different modes of patient education and delivered by a variety of healthcare providers, showed a positive result in adherence to medication. No single assessment provided a comprehensive measure of adherence to either medication or exercise.

Conclusions

The results underscore the complexity of non-adherence, its changing pattern and dependence on multi-level factors, the need to involve all stakeholders in all steps, the absence of a gold standard for screening and the requirement of multi-component interventions to manage it.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Patient Care Team, Health services research

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Non-adherent behaviour is common among people with chronic diseases; for example, 30–80% of people with rheumatoid arthritis do not adhere to treatment at some point of their disease, potentially leading to more disease activity, unnecessary treatment adaptations, loss of quality of life and increased healthcare costs.

What does this study add?

Non-adherence is triggered by multiple determinants, many of which are not modifiable, and none of which stands as a sole predictor of possible non-adherent behaviour.

Non-adherence can be assessed by multiple instruments; however, no gold standard exists.

Social factors, healthcare-related factors, disease characteristics, as well as therapy-related factors play a potentially important role in adherence; consequently, multicomponent interventions have proven to be the most effective response to non-adherent behaviours.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

This systematic review has formed the basis of 2020 EULAR points to consider how to facilitate adherence in people with RMDs.

INTRODUCTION

Thirty per cent to eighty per cent of people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) do not follow the prescribed treatment plan. This non-adherent behaviour has a negative impact on pharmacological and/or non-pharmacological interventions and keeping appointments of follow-up visits.1–5 Moreover, being non-adherent is associated with worse clinical outcomes, such as increased risk of cardiovascular disease, decreased functioning and loss of health-related quality of life.2–7 Strategies to prevent and/or manage non-adherence are thus essential to achieve an optimal disease outcome.4 6 7 Many EULAR recommendations for the management of specific RMDs highlight the importance of adherence to achieve the desired effect of interventions.8–11 However, these recommendations do not orient healthcare providers on how to work collaboratively with the patients to support them to adhere to their treatment plans.

A EULAR taskforce was formed to focus on non-adherence across RMDs. Non-adherence affects most types of RMDs and interventions; moreover, it is a complex behaviour that concerns all healthcare providers in rheumatology. An example of the complexity is the influence of a social context. Therefore, successful interventions depend not only on the capability and motivation of the individual patient, but also on contextual factors such as the capability and motivation of, for instance, a spouse or a caregiver.12 To facilitate a multidisciplinary, multifaceted approach to support adherent behaviour in people with RMDs, taking all these factors into account, the taskforce set out to identify and critically appraise evidence for preventing, screening, assessing and managing non-adherence.

METHODS

We performed a systematic review of systematic reviews (SR) following the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration,13 and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.14 According to the EULAR Standard Operating Procedures,15 an international expert task force was formed, including people with RMDs and representatives from relevant healthcare-provider groups: nurses, occupational therapists, psychologists, physiotherapists, pharmacists and rheumatologists. The task force developed and formulated the following clinical questions with the aim of covering the entire therapeutic process: (1) What strategies are efficacious in facilitating adherent behaviour? (2) What are the factors (barriers, facilitators and so on) that need to be considered to minimise or reduce non-adherence? (3) What is the impact of shared decision making (SDM) and of effective communication on non-adherence? (4) What are the practical things we can do in order to prevent non-adherence? (5) What are the effects of non-adherence on outcome? (6) How is non-adherence screened/detected? (7) Which healthcare providers are responsible for facilitating adherent behaviour? All these questions were translated into their corresponding PICO (Population; Intervention/factor; Comparator; Outcome; in addition, the type of study) formulae (table 1).

Table 1.

The clinical questions/PICOs addressed in this review. Questions #1 to #5 and #7 were answered on the basis of the articles identified in the first literature search. An additional literature search was performed to answer question #6 (online supplemental A)

| # | Clinical question | P | I | C | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | What strategies are efficacious in facilitating adherent behaviour? | Adults with any RMD | Any intervention or strategy managing non-adherence | SoC or other strategy | Adherence |

| 2 | What are the factors (barriers, facilitators) that need to be considered to minimise or reduce non-adherence? | – | – | Barriers and facilitators of adherence | |

| 3 | What is the impact of SDM and of effective communication on non-adherence? | SDM and effective communication | – | Adherence | |

| 4 | What are the practical things we can do in order to prevent non-adherence? | Effective interventions or strategies for enhancing adherence | – | Components of intervention | |

| 5 | What are the effects of non-adherence on outcome? | (Non-)Adherence | – | Outcome: Treatment effect, Function Disability Structural damage Fracture |

|

| 6 | How is non-adherence screened/detected? | Measurement or screening instruments | – | Screening performance Metric properties |

|

| 7 | Which healthcare providers are responsible for managing non-adherence? | Effective interventions or strategies for enhancing adherence | – | Health-care provider performing intervention |

PICO, Population; Intervention/factor; Comparator; Outcome; RMD, rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease; SoC, standard of care; SDM, shared decision making.

rmdopen-2020-001432supp001.pdf (190.4KB, pdf)

Search strategy

We conducted an electronic search of the following databases: Medline (via PubMed), Embase, CINAHL and Cochrane databases, from inception until 12 June 2018. Due to the broad spectrum of the topic, the task force decided to limit the search to the most important/frequent topics, being ‘drug therapy’, ‘exercise’, ‘nutrition’ and ‘visits’. We used comprehensive free text and MeSH synonyms for ‘adherence to drug therapy’, ‘adherence to exercise’, ‘adherence to diet’ and ‘adherence to visits’, plus synonyms of RMDs, with a filter for SR. ‘Exercise’ in this context refers to any physical activity, exercise or training; ‘visits’ mean regular medical check-ups with a healthcare provider. Additionally, a search strategy was developed to capture studies of instruments to assess adherence in RMDs. The electronic search strategies are available as a supplemental file (online supplemental A). We limited the search to reviews in adults and articles published in English during the last 10 years. It was decided by the task force to exclude children and adolescents (below the age of 18) from the literature search, as their non-adherent behaviour differs from that of adults, mainly on its great reliance on social support of caregivers.12

Study selection

The selection criteria of the studies were different for each of the questions and based on their specific PICO (table 1). Two authors (JBN, AdT) independently assessed the electronic search results for each of the questions. They first screened studies by title and then by abstract. When an article title seemed relevant, the abstract was reviewed for eligibility. If there was any doubt, the full text of the article was retrieved and appraised for possible inclusion. Any differences among the two authors were discussed, and if necessary, a third author (LC) was referred to for arbitration. A reason for exclusion was recorded in all cases if the article was not eligible or excluded (online supplementals B–H).

rmdopen-2020-001432supp008.pdf (111.9KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001432supp002.pdf (206.9KB, pdf)

Risk of bias assessment

Cochrane SR were included without further critical appraisal, as it is mandatory for them to follow rigorous methods.13 Any other SR underwent a critical appraisal by one author (VR), supervised by the methodologist (AdT), using the AMSTAR 2 tool.16 The quality and risk of bias of the original studies were obtained directly from the published SR.

Data extraction and synthesis

Three authors (VR, LC and JBN) extracted the data, supervised by the methodologist (AdT). Data included design, population, intervention or factors studied, comparator (if applicable), outcome(s) measured and results.

The results were synthesised qualitatively for each clinical question. No meta-analysis was intended, as the heterogeneity across studies in terms of population, interventions and outcomes measured precluded such quantitative approach.

RESULTS

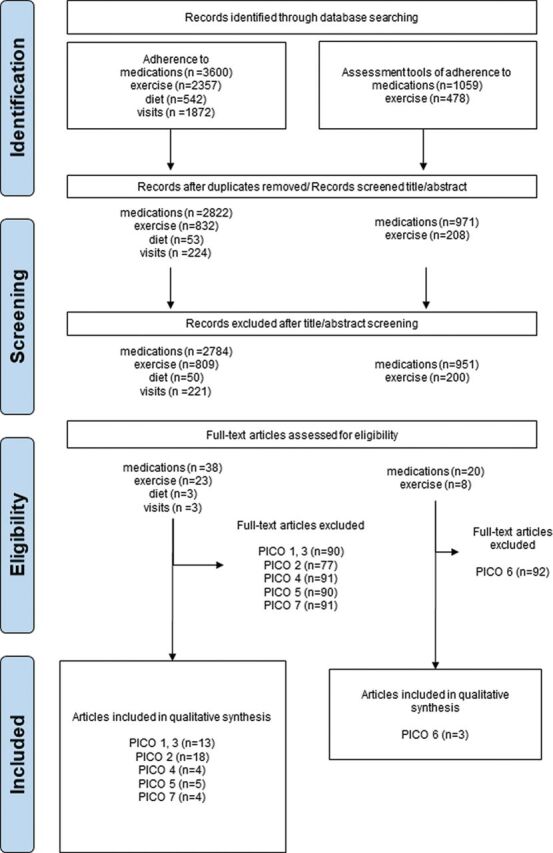

The search strategies yielded 9908 records, of which 3600 were related to adherence to medication, 2357 to exercise, 542 to diet, 1872 to visits and 1537 to the screening or assessment of adherence in RMD. After exclusion of duplicates and title/abstract screening, 95 studies were analysed in full text. According to the different inclusion and exclusion criteria, a different number of papers was included for each PICO. The PRISMA flowchart of the study selection is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. This flow chart shows the study selection for the search strategies and PICOs. As the PICOs had different exclusion and inclusion criteria, the number of excluded and included articles varies. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PICO, Population; Intervention/factor; Comparator; Outcome.

Risk of bias of the included SR

The quality of the SR was in general low. The quality of the included individual studies is described for each clinical question (online supplementals B–H).

Population of the included studies

There are more than 200 RMDs;17 however, the studies found in the reviews dealing with non-adherence and RMDs contained only eight different RMDs: rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoporosis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), osteoarthritis (OA), gout, spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis and low back pain.

Clinical question 1: what strategies are efficacious in facilitating adherent behaviour?

We included studies examining interventions aiming at improving non-adherent behaviour in comparison to standard care or other interventions. We searched for articles regarding medication/exercise adherence, adherence to diet/visits (See full report in online supplemental_B_PICO_1).

The screening by title and abstract yielded 38 studies to be appraised in full-text, of which four were SR on interventions to improve adherence to medication,15 18–20 eight SR on adherence to exercise21–28 and one on adherence to scheduled visits.29 We did not find any reviews regarding adherence to diet specifically in RMDs. In total, these reviews included 17 original studies on adherence to medication,30–46 33 on exercise or physical activity33 47–79 and three on visits.80–82

Due to the variety of interventions, we classified them into six categories: (1) educational (enhance patient knowledge), (2) behavioural (providing incentives for medication taking), (3) cognitive behavioural (altering thinking patterns) and (4) multicomponent intervention (multiple strategies used).18 83 For exercise, two categories were added: (5) motivational (increasing motivation) and (6) supervised/class-based exercises. Interventions that did not fit into these categories were classified as ‘others’, such as computer-assisted video instructions (to conventional education)77 or cost-free programmes compared to fee-based-programmes.76

The results were very heterogeneous in terms of diagnosis, interventions, outcome measures (see clinical question 6) and in regard of effectiveness. More than half of all interventions (n=29, 54.7%) included an educational or behavioural approach. Among the 53 studies included in the SR, 29 (54.7%) documented a small statistically significant effect on adherence. Among the remaining studies, six documented an unclear effect, and in 18 studies, no statistical significance was reached. All three multicomponent interventions showed a positive result in adherence to medication. Studies using cognitive behavioural or motivational approaches showed positive results; however, only three such studies were included in the SR (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the included studies, PICO 1

| Dx | Edu | Beh | CBT | Mot | Sup | MCo | Oth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication | RA | 3+/3− | 1+/1− | 1+ | 2+ | 1~ | ||

| SLE | 1+ | 1− | ||||||

| Psoriasis | 1+ | |||||||

| OP | 1~/1− | |||||||

| Total | 4+/3− | 1+/2− | 1+ | 3+ | 2~/1− | |||

| Exercise | OA | 2+/4− | 3− | 1+ | 2+/1− | 3+/2− | ||

| RA | 2+ | 3+/2− | 3~ | |||||

| Mixed | 1+ | 1+ | ||||||

| CBP | 1~ | 1+ | 1+ | |||||

| Total | 5+/4− | 4+/1~/5− | 2+ | 2+/1− | 1+/3~ | 3+/2− | ||

| Visits | RA | 3+ | ||||||

| SLE | ||||||||

| Total | 3+ |

Beh, behavioural interventions; CBP, chronic back pain; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; Dx, diagnosis; Edu, educational interventions; MCo, multicomponent interventions; Mot, motivational interventions; OA, osteoarthritis; OP, osteoporosis; Oth, other interventions; PICO, Population; Intervention/factor; Comparator; Outcome; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; Sup, supervised exercise; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

The numbers indicate the count of the studies. Numbers followed with a ‘+’ indicate significant increase in adherent behaviour, ‘−’ means no increase in adherent behaviour and ‘~’ means unclear results.

Clinical question 2: what are the factors (barriers, facilitators) that need to be considered to minimise or reduce non-adherence?

We included SR, specifically aiming at describing barriers or facilitators of adherence to medication or to exercise or physical activity (See full report in online supplemental_C_PICO_2). After excluding narrative reviews, expert opinions and reviews on interventions, 15 SR on factors affecting medication non-adherence84–98 and four on exercise99–102 were included.

rmdopen-2020-001432supp003.pdf (373.4KB, pdf)

Determinants for medication non-adherence are multi-faceted.84–98 Some factors may change over time and can act both as a cause and as a consequence of non-adherence. For example, clinical improvement seems to increase non-adherence behaviour. This may lead to worsening of symptoms which may urge patients to become more adherent.90

Some factors are not modifiable, for example, age and gender, and none is considered an isolated predictor of non-adherence.84 87 88 In their SR, Kardas & Lewek identified 771 individual factors related to medication non-adherence, covering 19 different diseases.90 They grouped their results into 40 clusters, mapped into the five WHO categories: socio-economic factors, healthcare team and system-related factors, condition-related factors, therapy-related factors, patient-related factors.103

Only four reviews addressed factors related to adherence to exercise.99–102 Similar to adherence to medication, adherence to exercise or physical activity is affected by multiple determinants. A SR, including low risk of bias studies, demonstrated that knowledge, skills, social or professional identity, beliefs about capabilities, optimism, beliefs about consequences and reinforcement influence adherence behaviour to exercise among patients with hip or knee OA.99 The Cochrane mixed methods review by Hurley & Dickson concluded that (1) better information and advice about the safety and value of exercise, (2) exercise tailored to individuals’ preferences, abilities and needs and (3) verbalisation of inappropriate health beliefs and better support, reduced non-adherent behaviour to exercise.100

Clinical question 3: what is the impact of shared decision making (SDM) and of effective communication on non-adherence?

To answer clinical question 3, all interventions included in the SR for PICO 1 were reviewed in detail, specifically seeking components of effective communication or SDM. Although no evidence was found specifically on the impact of SDM or effective communication on non-adherence in RMDs (See full report in online supplemental_D_PICO_3), the results to the next clinical question were very much related.

rmdopen-2020-001432supp004.pdf (155.9KB, pdf)

Clinical question 4: what are the practical things we can do in order to prevent non-adherence?

To better guide HCP in clinical routine, to better support patients in their adherence, we searched studies for useful and effective ‘everyday’ ideas and suggestions. All interventions proven effective in the SR of PICO 1 were reviewed in detail. The individual components of the effective interventions were collected and summarised (See full report in online supplement_E_PICO_4).

rmdopen-2020-001432supp005.pdf (123.8KB, pdf)

One important practical aspect was patient education (PE), defined, according to the EULAR recommendations, as a ‘planned interactive learning process designed to support and enable people to manage their life with inflammatory arthritis and optimise their health and well-being’.10 Five SR including 51 studies explored the association between (different) modes of PE and adherence in people with RMDs. Fifteen studies had a positive impact on non-adherence, nine of which were studies on medication,30 31 36 37 39–42 104 and six on exercise.50 52 66 70 79 105 Nine studies showed a positive, but not statistically significant effect; five studies on medication,32 43 45 105 106 and four on exercise.53 55 61 75 The PE modes to enhance adherence to medication varied greatly: daily text messages to provide reminders and education,41 information and written materials,31 42 chart visualisation of disease progression,37 discussion of patient-reported outcome measures (=PROMs),42 counselling and advice,45 motivational interview.43 106 The PE interventions for adherence to exercise also were varied: consultations,52 55 75 105 motivational approaches,70 physical activity advice50 and verbal (recorded tapes) and visualised (videos) cues to prompt correct performance of exercise.53 Regarding the content of the PE to improve medication adherence, this included information about drugs,31 36 disease process,31 36 physical exercise,31 joint protection,31 42 pain control,31 42 coping strategies31 and lifestyle changes.36 42 The studies which focused on PE to improve adherence to exercise include additional information about physical exercise, endurance activities (walking, swimming, bicycling), advice on energy conservation and joint protection.105 The mode of delivering PE was diverse: verbally, either by face to face,31 or by telephone,30 written, as in leaflets,31 or in text messages,39 41 and visualised, as in charts.37

In addition to PE, other practical things to prevent non-adherence were mentioned in the studies. Patients should be given the ability to express questions and doubts.36 Physicians and health professionals in rheumatology (HPRs) should review the plans and strategies and provide feedback and solve any doubts.104 Adherence behaviour is supported by interventions that are individualised or tailored according to predefined goals and preferences of the patient.40 50 66 Effective interventions included the encouragement of patients to set realistic goals in planning their treatment regimens, and the training of patients in proper execution of physical exercises.105 They also included photos displaying exercises and explanatory written information,79 and discussed issues of non-adherence, possible alternatives and solutions with the patient105 (table 3). Following the perceptions of healthcare providers, organisational aspects, such as limited consultation time, were the main obstacles to effective communication.52 Social support58 60 62 63 67 68 was used to support adherence to physical activity and exercises. Reminders did not increase the use of hydroxychloroquine but to follow up visits.39

Table 3.

Summary of practical things we can do in order to prevent non-adherence

| Medication adherence | |

|---|---|

| Practical thing we can do | Examples/descriptions |

| Education/information should include information about |

|

| Education/information can be delivered |

|

| Cueing | For example: pairing medication taking with an established behaviour such as brushing teeth |

| Monitoring | For example: using a calendar to track medication taking |

| Positive reinforcement | For example: praising and rewarding with tokens that are exchanged for special privileges |

| Possibility to express questions and doubts | Patients should have the possibility to express questions and doubts |

| Review of plans/strategies | Physician and other health professionals should review the plans/strategies and give feedback/answers |

| Individualised/tailored treatment | Individualised/tailored treatment according to patient preferences and goals |

| Exercise adherence | |

| Practical thing we can do | Examples/descriptions |

| More consults/time | Overcome the constraint of consultation time |

| Use psychosocial factors relevant for the motivational approach as proxy efficacy | Proxy efficacy refers to patients’ confidence in their therapists’ ability to function effectively on their behalf |

| Education/information should include information about |

|

| Discuss problems | Discuss problems regarding exercise adherence and offer solutions |

| Encourage patients to take responsibility | For example: to plan their treatment regimens, discuss intentions and help recasting unrealistic plans |

| Individualised/tailored treatment | Individualised physical activity advice and tailored graded exercise programme according to the preferences and goals of the patient. |

| Train in proper execution of physical exercises | Photos displaying these exercises and explanatory written information |

Clinical question 5: what are the effects of non-adherence on outcome?

To answer clinical question 5, all individual studies included in the first SR were reviewed. Studies were included if, besides adherence, other clinical outcomes, such as disease activity or patient’s perspective, were measured and the association with adherence analysed (See full report in online supplemental_F_PICO_5).

rmdopen-2020-001432supp006.pdf (148.6KB, pdf)

None of the included studies specifically focused or analysed the impact of non-adherent behaviour on health outcomes. However, in some studies, differences in clinical outcomes were seen between groups of patients with high adherence scores compared with less adherent patients. The association was evident in terms of improvement in disease severity,37 39 41 42 pain,37 41 42 79 functional status,37 40–42 70 79 fatigue,40 depression40, quality of life37 41 42 70 and physical activity levels.50 52 66 105

Clinical question 6: how is non-adherence screened/detected?

For this question, the type of studies targeted were validation studies of questions, questionnaires, tailored assessments and other kinds of measures to assess and/or screen non-adherence in people with RMDs (See full report in online supplemental_G_PICO_6). While conducting our review, a SR of tools to assess adherence to medication, which passed our AMSTAR2 quality check, was presented at the Eular Congress.107 It included 242 validation studies, and identified four questionnaires (patient-reported outcome measures) that have been used to measure non-adherence to medication in inflammatory arthritis: the Compliance Questionnaire in Rheumatology (CQR),108 the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS),109 the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS)110 111 and the Medication Adherence Self-report Inventory (MASRI).112 The most commonly used measurement is the MMAS, although it is subject to a fee and not fully validated in rheumatology. The CQR and MASRI questionnaires are the most widely validated in rheumatology; however, the CQR is an 18-item questionnaire, and hence, most suitable for research purposes. Within rheumatology, the MASRI has only been used in SLE.113 The authors of the SR concluded that up to date, a simple, reliable and valid questionnaire to assess medication adherence in daily clinical practice is not available.

rmdopen-2020-001432supp007.pdf (196KB, pdf)

We then focused our SR on measurements of adherence to exercise. Three SR covering 162 individual studies and describing 76 ways of measuring non-adherence to prescribed exercise interventions were identified.114–116 Currently, there is no gold standard measurement of adherence to exercise. The existing ones can be categorised as (1) (self-developed) questionnaires, scales, interviews or surveys (eg, asking for exercise-frequencies)117; (2) diaries or logbooks (eg, counting frequencies)118 and (3) other type of assessments (eg, different types of monitors and devices, such as StepWatch Activity Monitor (SAM)).115 The majority of tools do not have a proper description or testing of their metric properties available, except for the Heart Failure Compliance Questionnaire,119 the Adherence to Exercise Scale for Older Patients (AESOP)120 and The Problematic Experiences of Therapy Scale121; however, none of these scales are specifically developed or tested among people with inflammatory arthritis.

Clinical question 7: which healthcare providers are responsible for managing non-adherence?

To answer clinical question 7, all interventions in the included SR that showed a positive effect were reviewed in detail (See full report in online supplemental_H_PICO_7). The healthcare providers delivering these effective interventions were ranked by frequency, rheumatologists or other physicians,37 42 52 79 105 nurses,31 104 pharmacists,30 36 physiotherapists,66 70 therapists,40 exercise physiologist50 and patient educators.43

DISCUSSION

This overview of SR allowed us to answer clinical questions regarding adherence in RMDs. Despite the lack of assessment standards and evidence for interventions, non-adherence is a behaviour that is assumed to lead to a worse outcome and should therefore be addressed.

The findings of these reviews informed a EULAR task force developing the 2020 EULAR points to consider for the prevention, screening, assessment and management of non-adherence in people with RMDs. The intention to use this type of review compared to others was to examine only the highest level of evidence. A strength of this type of review is that it provides an overall picture of findings. Therefore, a SR of SR is an ideal means to provide rapid evidence synthesis for clinical decision-makers with the evidence they need.122 123 A challenge in doing such overview is the risk of including data from individual studies more than once. This could happen if studies are included in two or more reviews. This would result in a misleading estimate.122 123 To overcome this obstacle, once we selected the reviews we analysed the results of the individual studies, including them only once.

The PICOs/clinical questions formulated in the first task-force meeting aimed to cover the entire therapeutic process. The questions focused on prevention, screening, assessment and management of non-adherent behaviour. We only included adults who are independent of caregivers. We believe that the inclusion of caregivers requires a comprehensive extension of the scope and search. Children and older people or people with cognitive limitation who are dependent on a guardian/carer need special attention in terms of non-adherence.12 For this group of people, non-adherence behaviour differs from that of adults, mainly due to the great reliance on social support of caregivers.12

Our main message from this review is that adherence is very complex in nature, and thus that there is no single explanation for non-adherence. This means, there is no single factor for being non-adherent, but multiple factors influencing each other. Nevertheless, most studies have not considered the individual factors leading to non-adherence, and consequently used one and the same approach for all patients. This might be one of the reasons why especially tailored multi-component strategies are more efficacious compared to single interventions. However, to be evaluated, these tailored multi-component strategies require complex methods, very large sample sizes to avoid noise and solid outcome measures, which do not seem to be available.

We did not find any review that examined the impact of SDM or effective communication on (non-)adherence. Furthermore, we did not find a clear definition of ‘effective communication’ in healthcare. Instead of ‘effective communication’ we found ‘patient education/information’ to be similar to the term ‘effective communication’ (as it was understood from the task force) and an important tool to support patients in their adherent behaviour. With regard to SDM, we found that patient-tailored approaches are more effective than non-tailored approaches. However, since the results did not answer question 3, we moved these findings to question 4.

In accordance to the very complex nature of non-adherence, there is no gold-standard for screening or assessing it. Moreover, when adherence is discussed directly by a healthcare provider, there will be a risk of socially desirable answers. Healthcare providers have to take this into account, when they are evaluating (non-)adherence to a treatment regimen.

We acknowledge that our review has certain limitations. Most of the SR and studies included focused only on osteoarthritis, gout, osteoporosis and RA. Other types of inflammatory arthritis are under-represented and this may have introduced a bias of the results. Most of the SR and studies had adherence to medication or exercise as outcome. Adherence to diet and clinical visits was under-represented in this review. Further, the data extraction was performed by only one researcher. A disadvantage of using a review of reviews is that there may be studies in recent years, which were not included in any review, and therefore are not included in this overview as well. In addition, SR of SR should not only summarise the evidence, but should also include a resynthesis of the data.122 123 Due to the high heterogeneity, we were not able to perform a meta-analysis across the different reviews. We have focused solely on the effectiveness of interventions to support adherent behaviour in people with RMDs. Feasibility, cost-effectiveness and other factors were not further considered. Healthcare providers have to take in mind that the results of this review are based on study context, which can be different to daily practice. Finally, all studies suffered from some methodological limitations that impacted the level of evidence.

In conclusion, the results underscore the complexity of non-adherence, its changing pattern and dependence on multi-level factors. As agreement is part of the definition of adherence in the sense, that people with RMDs have to agree to the treatment plan, the need to involve all stakeholders, meaning healthcare providers and people with RMDs in all phases of treatment (prevention, screening, assessment and management), became obvious. The absence of a gold standard for screening and assessing non-adherence, and the requirement of multi-component interventions to manage it, sets an agenda for future research.

Footnotes

Twitter: Fernando Estévez-López @FerEstevezLope1 and José B Negrón @negronjb.

Contributors: VR wrote the manuscript draft, directly supervised by TS, AdT and LC. CS performed the search strategies, JBN, AdT and LC selected the studies, VR assessed risk of bias of all SR, VR, LC and JBN extracted the data, and synthesised the results. LC and AdT reviewed processes and excluded articles, and tailored the synthesis reports. All other authors suggested and agreed upon the research questions, read the report prior to the manuscript, discussed results and made contributions to the text. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This Project was funded by EULAR (project number HPR037).

Competing interests: VR, PB, FEL, JBN, AI, MN, AM, EM, KV and AdT did not have competing interest to declare. TS has received grant/research support from AbbVie and Roche, has been consultant for AbbVie, Sanofi Genzyme, and has been paid speaker for AbbVie, Roche and Sanofi. DA has received grant/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Lilly, Medac, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi Genzyme and UCB, has been consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Lilly, Medac, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi Genzyme and UCB, and has been paid speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Lilly, Medac, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi Genzyme and UCB. JB has received grant/research support from Roche, and has been paid speaker for Roche and Lilly. RD has been paid speaker for MSD, AbbVie, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, Mylan and Sandoz. ED has received grant/research support from Independent Learning, Pfizer, combined funding for a research fellow from Celgene, Abbvie and Novartis, and has been paid instructor for Novartis to deliver training to nurses. LG has received grant/research support from Fresenius, Lilly, Pfizer and Sandoz, and has been consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi-Aventis and UCB Pharma. BvdB has been paid speaker for MSD, Abbvie and Biogen. MV has been paid speaker for Pfizer. LC has received grant/research support through her institute from Novartis, Pfizer, MSD, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, AbbVie and Gebro Pharma.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: No ethical approval is required for systematic reviews.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data including Endnote files are available upon reasonable request.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Den Bemt BJF, Zwikker HE, van den Ende CH, Van Den Ende CHM. Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2012;8:337–51. 10.1586/eci.12.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DiMatteo MR Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care 2004;42:200–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organisation Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Switzerland: World Health Organisation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Achaval S, Suarez-Almazor ME. Treatment adherence to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Clin Rheumtol 2010;5:313 10.2217/ijr.10.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Breukelen-van der Stoep DF, Zijlmans J, van Zeben D, et al. Adherence to cardiovascular prevention strategies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 2015;44:443–8. 10.3109/03009742.2015.1028997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nordgren B, Friden C, Demmelmaier I, et al. An outsourced health-enhancing physical activity programme for people with rheumatoid arthritis: exploration of adherence and response. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:1065–73. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:492–509. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1125–35. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zangi HA, Ndosi M, Adams J, et al. EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:954–62. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bech B, Primdahl J, Van Tubergen A, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the role of the nurse in the management of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:61–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allen KD, Warzak WJ. The problem of parental nonadherence in clinical behavior analysis: effective treatment is not enough. J Appl Behav Anal 2000;33:373–91. 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009;6:W–W. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galo JS, Mehat P, Rai SK, et al. What are the effects of medication adherence interventions in rheumatic diseases: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2015. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Der Heijde D, Daikh DI, Betteridge N, et al. Common language description of the term rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) for use in communication with the lay public, healthcare providers and other stakeholders endorsed by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:829–32. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Depont F, Berenbaum F, Filippi J, et al. Interventions to improve adherence in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disorders: a systematic review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0145076 10.1371/journal.pone.0145076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ganguli A, Clewell J, Shillington AC. The impact of patient support programs on adherence, clinical, humanistic, and economic patient outcomes: a targeted systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:711 10.2147/PPA.S101175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;11 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baillet A, Zeboulon N, Gossec L, et al. Efficacy of cardiorespiratory aerobic exercise in rheumatoid arthritis: meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:984–92. 10.1002/acr.20146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ezzat AM, MacPherson K, Leese J, et al. The effects of interventions to increase exercise adherence in people with arthritis: a systematic review. Musculoskeletal Care 2015;13:1 10.1002/msc.1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gay C, Chabaud A, Guilley E, et al. Educating patients about the benefits of physical activity and exercise for their hip and knee osteoarthritis. Systematic literature review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2016;59:174–83. 10.1016/j.rehab.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hammond A, Prior Y. The effectiveness of home hand exercise programmes in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Br Med Bull 2016;119:49–62. 10.1093/bmb/ldw024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jansons PS, Haines TP, O’Brien L. Interventions to achieve ongoing exercise adherence for adults with chronic health conditions who have completed a supervised exercise program: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2017;31:465–77. 10.1177/0269215516653995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Larkin L, Gallagher S, Cramp F, et al. Behaviour change interventions to promote physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 2015;35:1631–40. 10.1007/s00296-015-3292-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mazieres B, Thevenon A, Coudeyre E, et al. Adherence to, and results of, physical therapy programs in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Development of French clinical practice guidelines. Joint Bone Spine 2008;75:589–96. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nicolson PJ, Bennell KL, Dobson FL, et al. Interventions to increase adherence to therapeutic exercise in older adults with low back pain and/or hip/knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:791–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taneja A, Su’a B, Hill A. Efficacy of patient‐initiated follow‐up clinics in secondary care: a systematic review. Intern Med J 2014;44:1156–60. 10.1111/imj.12533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clifford S, Barber N, Elliott R, et al. Patient-centred advice is effective in improving adherence to medicines. Pharmacy World Sci 2006;28:165 10.1007/s11096-006-9026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hill J, Bird H, Johnson S. Effect of patient education on adherence to drug treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60:869–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Homer D, Nightingale P, Jobanputra P. Providing patients with information about disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs: individually or in groups? A pilot randomized controlled trial comparing adherence and satisfaction. Musculoskeletal Care 2009;7:78–92. 10.1002/msc.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brus HLM, van de Laar MAFJ, Taal E, et al. Effects of patient education on compliance with basic treatment regimens and health in recent onset active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57:146–51. 10.1136/ard.57.3.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Conn DL, Pan Y, Easley KA, et al. The effect of the arthritis self-management program on outcome in African Americans with rheumatoid arthritis served by a public hospital. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:49–59. 10.1007/s10067-012-2090-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ravindran V, Jadhav R. The effect of rheumatoid arthritis disease education on adherence to medications and followup in Kerala, India. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1460–1. 10.3899/jrheum.130350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ganachari M, Almas SA. Evaluation of clinical pharmacist mediated education and counselling of systemic lupus erythematosus patients in tertiary care hospital. Indian J Rheumatol 2012;7:7–12. 10.1016/S0973-3698(12)60003-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Palmer D. Assessment of the utility of visual feedback in the treatment of early rheumatoid arthritis patients: a pilot study. Rheumatol Int 2012;32:3061–8. 10.1007/s00296-011-2098-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van den Bemt BJF, den Broeder AA, van den Hoogen FHJ, et al. Making the rheumatologist aware of patients’ non-adherence does not improve medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 2011;40:192–6. 10.3109/03009742.2010.517214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ting TV, Kudalkar D, Nelson S, et al. Usefulness of cellular text messaging for improving adherence among adolescents and young adults with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2012;39:174–9. 10.3899/jrheum.110771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Evers AW, Kraaimaat FW, van Riel PL, et al. Tailored cognitive-behavioral therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis for patients at risk: a randomized controlled trial. Pain 2002;100:141–53. 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00274-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Balato N, Megna M, Di Costanzo L, et al. Educational and motivational support service: a pilot study for mobile‐phone‐based interventions in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2013;168:201–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, El Arousy N, et al. Arthritis education: the integration of patient-reported outcome measures and patient self-management. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30:899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McEvoy Devellis B, Blalock SJ, Hahn PM, et al. Evaluation of a problem-solving intervention for patients with arthritis. Patient Educ Couns 1988;11:29–42. 10.1016/0738-3991(88)90074-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lai PSM, Chua SS, Chan SP. Impact of pharmaceutical care on knowledge, quality of life and satisfaction of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:629–37. 10.1007/s11096-013-9784-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Solomon DH, Iversen MD, Avorn J, et al. Osteoporosis telephonic intervention to improve medication regimen adherence: a large, pragmatic, randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:477–83. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stockl KM, Shin JS, Lew HC, et al. Outcomes of a rheumatoid arthritis disease therapy management program focusing on medication adherence. J Manag Care Pharm 2010;16:593–604. 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.8.593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bossen D, Veenhof C, Van Beek KE, et al. Effectiveness of a web-based physical activity intervention in patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e257 10.2196/jmir.2662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Farr JN, Going SB, McKnight PE, et al. Progressive resistance training improves overall physical activity levels in patients with early osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2010;90:356–66. 10.2522/ptj.20090041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fries J, Carey C, McShane D. Patient education in arthritis: randomized controlled trial of a mail-delivered program. J Rheumatol 1997;24:1378–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Halbert J, Crotty M, Weller D, et al. Primary care: based physical activity programs: effectiveness in sedentary older patients with osteoarthritis symptoms. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2001;45:228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mayoux-Benhamou A, Giraudet-Le Quintrec J-S, Ravaud P, et al. Influence of patient education on exercise compliance in rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective 12-month randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2008;35:216–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ravaud P, Flipo R, Boutron I, et al. ARTIST (osteoarthritis intervention standardized) study of standardised consultation versus usual care for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee in primary care in France: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338:b421 10.1136/bmj.b421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schoo AMM, Morris M, Bui Q. The effects of mode of exercise instruction on compliance with a home exercise program in older adults with osteoarthritis. Physiotherapy 2005;91:79–86. 10.1016/j.physio.2004.09.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Williams NH, Amoakwa E, Belcher J, et al. Activity Increase Despite Arthritis (AIDA): phase II randomised controlled trial of an active management booklet for hip and knee osteoarthritis in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e452–58. 10.3399/bjgp11X588411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Basler HD, Bertalanffy H, Quint S, et al. TTM‐based counselling in physiotherapy does not contribute to an increase of adherence to activity recommendations in older adults with chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Pain 2007;11:31 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brosseau L, Wells GA, Kenny GP, et al. The implementation of a community-based aerobic walking program for mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis (OA): a knowledge translation (KT) randomized controlled trial (RCT): part I: the uptake of the Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). BMC Public Health 2012;12:871 10.1186/1471-2458-12-871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Frost KL Influence of a motivational exercise counseling intervention on rehabilitation outcomes in individuals with arthritis who received total hip replacement. University of Pittsburgh, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huffman KM, Sloane R, Peterson MJ, et al. The impact of self-reported arthritis and diabetes on response to a home-based physical activity counselling intervention. Scand J Rheumatol 2010;39:233–9. 10.3109/03009740903348973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. John H, Hale ED, Treharne GJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural patient education intervention vs a traditional information leaflet to address the cardiovascular aspects of rheumatoid disease. Rheumatology 2013;52:81–90. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Knittle K, De Gucht V, Hurkmans E, et al. Targeting motivation and self-regulation to increase physical activity among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol 2015;34:231–8. 10.1007/s10067-013-2425-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. O’Brien D, Bassett S, McNair P. The effect of action and coping plans on exercise adherence in people with lower limb osteoarthritis: a feasibility study. NZJ Physiother 2013;41:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Van den Berg M, Ronday H, Peeters A, et al. Using internet technology to deliver a home‐based physical activity intervention for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2006;55:935–45. 10.1002/art.22339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hurkmans EJ, Van den Berg MH, Ronday KH, et al. Maintenance of physical activity after Internet-based physical activity interventions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2010;49:167–72. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell RT, et al. Long-term impact of fit and strong! On older adults with osteoarthritis. Gerontologist 2006;46:801–14. 10.1093/geront/46.6.801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McCarthy C, Mills P, Pullen R, et al. Supplementation of a home-based exercise programme with a class-based programme for people with osteoarthritis of the knees: a randomised controlled trial and health economic analysis. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England) 2004;8:2015 10.3310/hta8460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pisters MF, Veenhof C, de Bakker DH, et al. Behavioural graded activity results in better exercise adherence and more physical activity than usual care in people with osteoarthritis: a cluster-randomised trial. J Physiother 2010;56:41–7. 10.1016/S1836-9553(10)70053-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Brodin N, Eurenius E, Jensen I, et al. Coaching patients with early rheumatoid arthritis to healthy physical activity: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2008;59:325–31. 10.1002/art.23327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sjöquist ES, Brodin N, Lampa J, et al. Physical activity coaching of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in everyday practice: a long‐term follow‐up. Musculoskeletal Care 2011;9:75–85. 10.1002/msc.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell RT, et al. Fit and strong: bolstering maintenance of physical activity among older adults with lower-extremity osteoarthritis. Am J Health Behav 2010;34:750–63. 10.5993/AJHB.34.6.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Vong SK, Cheing GL, Chan F, et al. Motivational enhancement therapy in addition to physical therapy improves motivational factors and treatment outcomes in people with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:176–83. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Friedrich M, Gittler G, Halberstadt Y, et al. Combined exercise and motivation program: effect on the compliance and level of disability of patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:475–87. 10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90059-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lamb SE, Williamson EM, Heine PJ, et al. Exercises to improve function of the rheumatoid hand (SARAH): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:421–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60998-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Manning VL, Hurley MV, Scott DL, et al. Education, self‐management, and upper extremity exercise training in people with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:217–27. 10.1002/acr.22102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. O’Brien A, Jones P, Mullis R, et al. Conservative hand therapy treatments in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology 2006;45:577–83. 10.1093/rheumatology/kei215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bennell KL, Kyriakides M, Hodges PW, et al. Effects of two physiotherapy booster sessions on outcomes with home exercise in people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1680–7. 10.1002/acr.22350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cochrane T, Davey R, Matthes SE. Randomised controlled trial of the cost-effectiveness of water-based therapy for lower limb osteoarthritis. Health Technol Assess 2007. 10.3310/hta9310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lysack C, Dama M, Neufeld S, et al. Compliance and satisfaction with home exercise: a comparison of computer-assisted video instruction and routine rehabilitation practice. J Allied Health 2005;34:76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Talbot LA, Gaines JM, Huynh TN, et al. A home‐based pedometer‐driven walking program to increase physical activity in older adults with osteoarthritis of the knee: a preliminary study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:387–92. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tüzün S, Cifcili S, Akman M, et al. How can we improve adherence to exercise programs in patients with osteoarthritis?: a randomized controlled trial. Turkish J Geriatrics 2012;15:3. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hewlett S, Mitchell K, Haynes J, et al. Patient‐initiated hospital follow‐up for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2000;39:990–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/39.9.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kirwan JR, Mitchell K, Hewlett S, et al. Clinical and psychological outcome from a randomized controlled trial of patient‐initiated direct‐access hospital follow‐up for rheumatoid arthritis extended to 4 years. Rheumatology 2003;42:422–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hewlett S, Kirwan J, Pollock J, et al. Patient initiated outpatient follow up in rheumatoid arthritis: six year randomised controlled trial. bmj 2005;330:171 10.1136/bmj.38265.493773.8F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Greenley RN, Kunz JH, Walter J, et al. Practical strategies for enhancing adherence to treatment regimen in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1534–45. 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182813482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. De Vera MA, Marcotte G, Rai S, et al. Medication adherence in gout: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1551–9. 10.1002/acr.22336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Devine F, Edwards T, Feldman SR. Barriers to treatment: describing them from a different perspective. Patient Prefer Adherence 2018;12:129–33. 10.2147/PPA.S147420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Dockerty T, Latham SK, Smith TO. Why don’t patients take their analgesics? A meta-ethnography assessing the perceptions of medication adherence in patients with osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int 2016;36:731–9. 10.1007/s00296-016-3457-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Fautrel B, Balsa A, Van Riel P, et al. Influence of route of administration/drug formulation and other factors on adherence to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis (pain related) and dyslipidemia (non-pain related). Curr Med Res Opin 2017;33:1231–46. 10.1080/03007995.2017.1313209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Goh H, Kwan YH, Seah Y, et al. A systematic review of the barriers affecting medication adherence in patients with rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int 2017;37:1619–28. 10.1007/s00296-017-3763-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hope HF, Bluett J, Barton A, et al. Psychological factors predict adherence to methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis; findings from a systematic review of rates, predictors and associations with patient-reported and clinical outcomes. RMD Open 2016;2:e000171 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kardas P, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M. Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol 2013;4:91 10.3389/fphar.2013.00091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kelly A, Tymms K, Tunnicliffe DJ, et al. Patients’ attitudes and experiences of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis: a qualitative synthesis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2018;70:525–32. 10.1002/acr.23329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lopez-Gonzalez R, Leon L, Loza E, et al. Adherence to biologic therapies and associated factors in rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33:559–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mehat P, Atiquzzaman M, Esdaile JM, et al. Medication nonadherence in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:1706–13. 10.1002/acr.23191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pasma A, Van’t Spijker A, Hazes JMW, van’t Spijker A, Hazes JM, et al. Factors associated with adherence to pharmaceutical treatment for rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013;43:18–28. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Scheepers L, van Onna M, Stehouwer CDA, et al. Medication adherence among patients with gout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018;47:689–702. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Scheiman-Elazary A, Duan L, Shourt C, et al. The rate of adherence to antiarthritis medications and associated factors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 2016;43:512–23. 10.3899/jrheum.141371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. van Mierlo T, Fournier R, Ingham M. Targeting medication non-adherence behavior in selected autoimmune diseases: a systematic approach to digital health program development. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129364 10.1371/journal.pone.0129364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Vangeli E, Bakhshi S, Baker A, et al. A systematic review of factors associated with non-adherence to treatment for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Adv Ther 2015;32:983–1028. 10.1007/s12325-015-0256-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Dobson F, Bennell KL, French SD, et al. Barriers and facilitators to exercise participation in people with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis: synthesis of the literature using behavior change theory. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2016;95:372–89. 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Hurley M, Dickson K, Hallett R, et al. Exercise interventions and patient beliefs for people with hip, knee or hip and knee osteoarthritis: a mixed methods review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;4:CD010842 10.1002/14651858.CD010842.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kanavaki AM, Rushton A, Efstathiou N, et al. Barriers and facilitators of physical activity in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017042 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Larkin L, Kennedy N. Correlates of physical activity in adults with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Phys Act Health 2014;11:1248–61. 10.1123/jpah.2012-0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sabaté E Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Rapoff MA, Belmont J, Lindsley C, et al. Prevention of nonadherence to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications for newly diagnosed patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Health Psychol 2002;21:620 10.1037/0278-6133.21.6.620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Brus HL, Van De Laar MA, Taal E, et al. Effects of patient education on compliance with basic treatment regimens and health in recent onset active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57:146–51. 10.1136/ard.57.3.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Zwikker HE, van den Ende CH, van Lankveld WG, et al. Effectiveness of a group-based intervention to change medication beliefs and improve medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2014;94:356–61. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Puyraimond-Zemmour D, Romand X, Lavielle M, et al. SAT0629 there are 4 main questionnaires to assess adherence in inflammatory arthritis but none of them perform well: a systematic literature review. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 108. de Klerk E, Van der Heijde D, Van der Tempel H, et al. Development of a questionnaire to investigate patient compliance with antirheumatic drug therapy. J Rheumatol 1999;26:2635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew A. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res 2000;42:241–7. 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel‐Wood M, et al. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens 2008;10:348–54. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 111. Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 1986;24:67–74. 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS 2002;16:269–77. 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Shishov M, Koneru S, Graham T, et al. The medication adherence self-report inventory (MASRI) can accurately estimate adherence with medications in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Arthritis Rheumatism 2005;S188 Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ USA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Bollen JC, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, et al. A systematic review of measures of self-reported adherence to unsupervised home-based rehabilitation exercise programmes, and their psychometric properties. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005044 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Frost R, Levati S, McClurg D, et al. What adherence measures should be used in trials of home-based rehabilitation interventions? A systematic review of the validity, reliability, and acceptability of measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil e1245 2017;98:1241–56. 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.08.482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Levy T, Laver K, Killington M, et al. A systematic review of measures of adherence to physical exercise recommendations in people with stroke. Clin Rehabil 2019;33:535–45. 10.1177/0269215518811903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Bennell KL, Egerton T, Bills C, et al. Addition of telephone coaching to a physiotherapist-delivered physical activity program in people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:246 10.1186/1471-2474-13-246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Alexandre NMC, Nordin M, Hiebert R, et al. Predictors of compliance with short-term treatment among patients with back pain. Revista Panamericana De Salud Pública 2002;12:86–95. 10.1590/S1020-49892002000800003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Evangelista LS, Berg J, Dracup K. Relationship between psychosocial variables and compliance in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung 2001;30:294–301. 10.1067/mhl.2001.116011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Hardage J, Peel C, Morris D, et al. Adherence to Exercise Scale for Older Patients (AESOP): a measure for predicting exercise adherence in older adults after discharge from home health physical therapy. J Geriatric Phys Therapy 2007;30:69–78. 10.1519/00139143-200708000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Kirby S, Donovan-Hall M, Yardley L. Measuring barriers to adherence: validation of the problematic experiences of therapy scale. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:1924–9. 10.3109/09638288.2013.876106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Blackwood D Taking it to the next level: reviews of sytematic reviews. HLA News 2016;2016(Winter):13. [Google Scholar]

- 123. Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, et al. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:15 10.1186/1471-2288-11-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2020-001432supp001.pdf (190.4KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001432supp008.pdf (111.9KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001432supp002.pdf (206.9KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001432supp003.pdf (373.4KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001432supp004.pdf (155.9KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001432supp005.pdf (123.8KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001432supp006.pdf (148.6KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2020-001432supp007.pdf (196KB, pdf)