Abstract

Objectives:

The diagnosis of an advanced cancer in young adulthood can bring one’s life to an abrupt halt, calling attention to the present moment and creating anguish about an uncertain future. There is seldom time or physical stamina to focus on forward thinking, social roles, relationships, or dreams. As a result, young adults (YAs) with advanced cancer frequently encounter existential distress, despair, and question the purpose of their life. We sought to investigate the meaning and function of hope throughout YAs’ disease trajectory; to discern the psychosocial processes YAs employ to engage hope; and to develop a substantive theory of hope of YAs diagnosed with advanced cancer.

Methods:

Thirteen YAs (ages 23–38) diagnosed with a stage III or IV cancer were recruited throughout the eastern and southeastern United States. Participants completed one semi-structured interview in-person, by phone or Skype, that incorporated an original timeline instrument assessing fluctuations in hope and an online sociodemographic survey. Glaser’s grounded theory methodology informed constant comparative methods of data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Results:

Findings from this study informed the development of the novel contingent hope theoretical framework, which describes the pattern of psychosocial behaviors YAs with advanced cancer employ to reconcile identities and strive for a life of meaning. The ability to cultivate the necessary agency and pathways to reconcile identities became contingent on the YAs’ participation in each of the psychosocial processes of the contingent hope theoretical framework: navigating uncertainty, feeling broken, disorienting grief, finding bearings, and identity reconciliation.

Significance of Results:

Study findings portray the influential role of hope in motivating YAs with advanced cancer through disorienting grief towards an integrated sense of self that marries cherished aspects of multiple identities. The contingent hope theoretical framework details psychosocial behaviors to inform assessments and interventions fostering hope and identity reconciliation.

Keywords: Hope, young adult, advanced cancer, identity reconciliation, grounded theory

Introduction

The diagnosis of an advanced cancer endangers deep-seeded cognitive schema, frequently driving individuals into an existential quest to discover the meaning of their illness, their life’s purpose, and mechanisms for sustaining hope (Lee, 2008). This diagnosis in young adulthood (ages 18–39) disrupts schema of enjoying long, healthy, fulfilling lives (Jones et al., 2011; Rosenberg & Wolfe, 2013). Life prior to cancer likely included excellent health and active engagement in social, vocational, and educational goals (Linebarger et al., 2014; Rosenberg & Wolfe, 2013). Treatment side-effects halt young adults’ (YAs) participation in developmental milestones and attention shifts to the possibility of death, management of side-effects, and the multitude of future unknowns (Lam, 2015; Lee, 2008; Linebarger et al., 2014; Pritchard et al., 2011). Core facets of their identity perish along with social and vocational roles, functional abilities, and autonomy (Jones et al., 2011; Linebarger et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2018; Rosenberg & Wolfe, 2013; Zebrack, 2011). These compounding stressors place YAs at risk for existential distress, hopelessness, despair, and desire for hastened death (Breitbart et al., 2000; Cassel, 1982; Chochinov et al., 1998; Mystakidou et al., 2008; Sachs et al., 2013).

Even though cancer ranks among the leading causes of death for YAs (American Cancer Society, 2018) we have minimal knowledge of factors that foster existential quality of life in this population. Research points to the role of hope in motivating behaviors among cancer survivors (Eliott & Olver, 2009; Nierop-van Baalen et al., 2016; Ngwenya et al., 2016). However, studies fail to address the developmentally unique perspectives of hope among YAs with advanced cancer such as starting careers, intimate relationships, fertility, and raising minor children (Arnett, 2000; Erikson, 1968; Levinson, 1978, 1996; Linebarger et al., 2014; Rosenberg & Wolfe, 2013). Given the high mortality rates and profound impact of hope in motivating behaviors, it becomes imperative to investigate the role hope plays in motivating YAs’ behaviors in and outside of treatment.

The purpose of this research is to discover how YAs with advanced cancer engage hope to cope with their life-limiting illness. Grounded theory methods inform this analysis and provide insight into psychosocial patterns of behavior involved in this understudied substantive area. Findings from this study will inform both clinical and scholarly understanding of hope as a contributor to existential quality of life among YAs with advanced cancer. Specifically, this study will establish a novel theoretical framework of psychosocial processes YAs with advanced cancer employ to preserve hope; thus, offering specific targets for assessing and cultivating hope among YAs with advanced cancer. This study’s specific aims are to (1) investigate the meaning and function of hope for YAs throughout their disease trajectory; (2) discern the psychosocial processes YAs employ to engage hope; and (3) develop a substantive theory of hope of YAs with advanced cancer.

Methods

This study incorporated Barney Glaser’s (1967, 1978, 1998) grounded theory methods. This methodology commonly appears in research examining psychosocial processes for engaging hope within the substantive areas of health, palliative care, grief, and loss (Bally et al., 2014; Duggleby, 2000; Duggleby & Wright, 2009; Holtslander & Duggleby, 2009; Penz & Duggleby, 2011). Grounded theory enables researchers to analyze the multivariate data gathered from participants’ stories of their day-to-day activities to formulate a theory that explains the core psychosocial processes and how YAs organize behaviors to cope with their problems (Glaser, 1998).

Research Sample and Data Sources

The study’s inclusion criteria were females and males ages 18–39, diagnosed with stage III, IV, metastatic, recurrent, or blood cancer. Participant recruitment followed theoretical sampling methods (Glaser, 1978). As data emerged within the theoretical framework, recruitment expanded to gather further perspectives from those newly diagnosed, male, and receiving multiple years of treatment. Interview nine marked theoretical saturation where further incidents no longer elaborated properties within categories of the theoretical framework. Four additional interviews were performed to confirm theoretical saturation, and to determine whether the theory met Glaser’s standards for theoretical legitimacy: fit, workability, relevance, and modifiability.

Participants learned about the study from healthcare providers, cancer support organizations, YA online communities, and other study participants. When participants initiated contact by email or phone, the investigator shared the purpose and requirements of the study. None of the participants had an established relationship with the investigator. After participants signed the informed consent form, they arranged a time and location for their interview. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the lead institution prior to participant recruitment. Participants received a $10 Walmart gift card for their participation.

Data Collection

Participants completed one semi-structured interview, a novel timeline tool assessing fluctuations in hope, The Hope Timeline, and an online survey capturing sociodemographic and cancer treatment variables. Interviews lasted 60–90 minutes and took place in person (n=8), by telephone (n=4) or Skype (n=1). The lead investigator performed all of the interviews and has over two decades experience performing clinical and research-based interviews in oncology.

Interviews began by asking participants to share their thoughts, feelings, and actions at diagnosis. Next, the investigator asked participants to share about their lives with cancer utilizing probes such as: “What does hope mean to you?”; “What do you hope for?”; and “What helps you to maintain hope?” Appendix A displays the Interview Guide. As participants narrated their story, they were invited to complete The Hope Timeline (see Figure 1) with the following prompt: “This Hope Timeline allows you to draw your experiences with hope throughout your illness. Please include times that you saw as positive or high hopes and times that you saw as curveballs or challenges to your hopes.” Participants received cues to share details about pivotal Timeline moments such as: what was happening physically, who was involved, and what they were thinking and feeling. Participants utilized one to fourteen pages of the Timeline to document present and future hopes and revised their Timelines as the interview progressed, providing additional details and adjusting dates. Those participating in the interview remotely received guidance to verbally describe pivotal times in their disease trajectory when hope fluctuated so that the interviewer could graph these participants’ Hope Timeline trajectories.

Figure 1.

Hope Timeline

Data Analysis

The initial stage of this multivariate analysis, open coding, involved constant comparison of incidents with contemplation of similarities, differences, underlying patterns in the data, and initial properties of each category; subsequently introducing the main concern of participants. Coding of the Timelines occurred immediately after the coding of transcripts and enabled the researcher an additional data source in which to explore patterns in the individual, interpersonal, and structural factors that influenced the maintenance of hope. The researcher was able to incorporate constant comparison between participants’ Timelines to inform interview questions and the development of a theoretical framework which demonstrates how YAs engage hope to cope with their life-limiting illness.

Selective coding entailed the delimiting of data to the core category which serves as the nucleus and driving force of the emerging theory, and other interrelated subcategories. The final coding step, theoretical coding, explored how relationships between concepts minimized, maximized, or changed the core category. Glaser (1998) believed that the multivariate hypothesis testing involved with sorting of theoretical memos, and relationships between categories and properties results in an integrated parsimonious theory that details the psychosocial processes individuals engage to relieve distress caused by their main life concern. To maintain theoretical sensitivity, the lead investigator waited until the solidification of the theoretical framework (post interview nine) before seeking suggestions on theoretical legitimacy from four YAs living several years with advanced cancer and a panel of YA oncology practitioners and researchers. Computer software programs supported the analysis of qualitative (MAXQDA) (VERBI, 2018) and descriptive data (SPSS, v23.0, IBM, 2013).

Strategies to Enhance Rigor

The research team incorporated three standards to enhance validity and reliability: Tong, Sainsbury and Craig’s (2007) consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ); Glaser’s (1998) test of legitimacy; and Hutchinson’s (2015) criteria for verifying rigor, trustworthiness, and theoretical applicability. Quality checks included development of an interview guide; recording and transcribing interviews and field notes; and maintaining an audit trail. The lead researcher transcribed all interviews verbatim and compared the accuracy of data between recordings and transcriptions until achieving 100% congruence. Analytic and theoretical memos captured theoretical sampling methods, nonparticipation, code definitions, category development, changes to the Interview Guide, and decisions made while delineating the substantive theory.

Results

The final study sample included thirteen YAs diagnosed with advanced cancer. Table 1 presents the study sample’s descriptive characteristics. Participants were between ages 23–38, predominantly female (76.9%), and identified as non-Hispanic White (76.9%), Hispanic or Latino (15.4%) and Asian (7.7%). Five participants (38.5%) received a cancer diagnosis of stage III and eight (61.5%) were diagnosed with stage IV. Their cancer types included blood, breast, colorectal, genitourinary, gynecological, and head and neck. Two participants were diagnosed with two primary cancers. Nine (69.2%) participants were on active treatment.

Table 1.

Sample Sociodemographic and Cancer Treatment Characteristics

| Category | N (%) | M(SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at initial diagnosis | 26.69 (6.49) | 17–38 | |

| Current age | 30.53 (6.05) | 23–38 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3 (23.1) | ||

| Female | 10 (76.9) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 10 (76.9) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Asian | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Black | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Education | |||

| Some high school | 1 (7.7) | ||

| High school graduate | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Some college | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 5 (38.5) | ||

| Graduate degree | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Full time work | 5 (38.5) | ||

| Part time work | 4 (30.8) | ||

| On medical leave | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 7 (53.8) | ||

| Partnered | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Single | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Divorced | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Widowed | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Living situation | |||

| Living with parents | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Living with own family | 5 (38.5) | ||

| Living with partner | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Living alone | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Minor children | |||

| Yes | 3 (23.1) | ||

| No | 10 (76.9) | ||

| Stage at initial diagnosis | |||

| I | 0 (0.0) | ||

| II | 0 (0.0) | ||

| III | 5 (38.5) | ||

| IV | 8 (61.5) | ||

| Type of cancer * | |||

| Blood | 5 (33.3) | ||

| Breast | 2(13.3) | ||

| Colorectal | 2 (13.3) | ||

| Genitourinary | 1 (6.7) | ||

| Gynecological | 4 (26.7) | ||

| Head and neck | 1 (6.7) | ||

| Cancer recurrence | |||

| Yes | 4 (30.8) | ||

| No | 9 (69.2) | ||

| Unsure | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Cancer metastasis | |||

| Yes | 6 (46.2) | ||

| No | 6 (46.2) | ||

| Unsure | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Currently on treatment | |||

| Yes | 9 (69.2) | ||

| No | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Types of treatment received** | |||

| Surgery | 9 (69.2) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 9 (69.2) | ||

| Radiation therapy | 5 (38.5) | ||

| Biological therapy | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Palliative care | 3 (23.1) | ||

| Hormone suppression | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Hospice | 0 (0.0) |

Two participants were diagnosed with two non-related cancers; thus, n does not equal 13

Several participants had more than one modality of treatment; thus, n does not equal 13

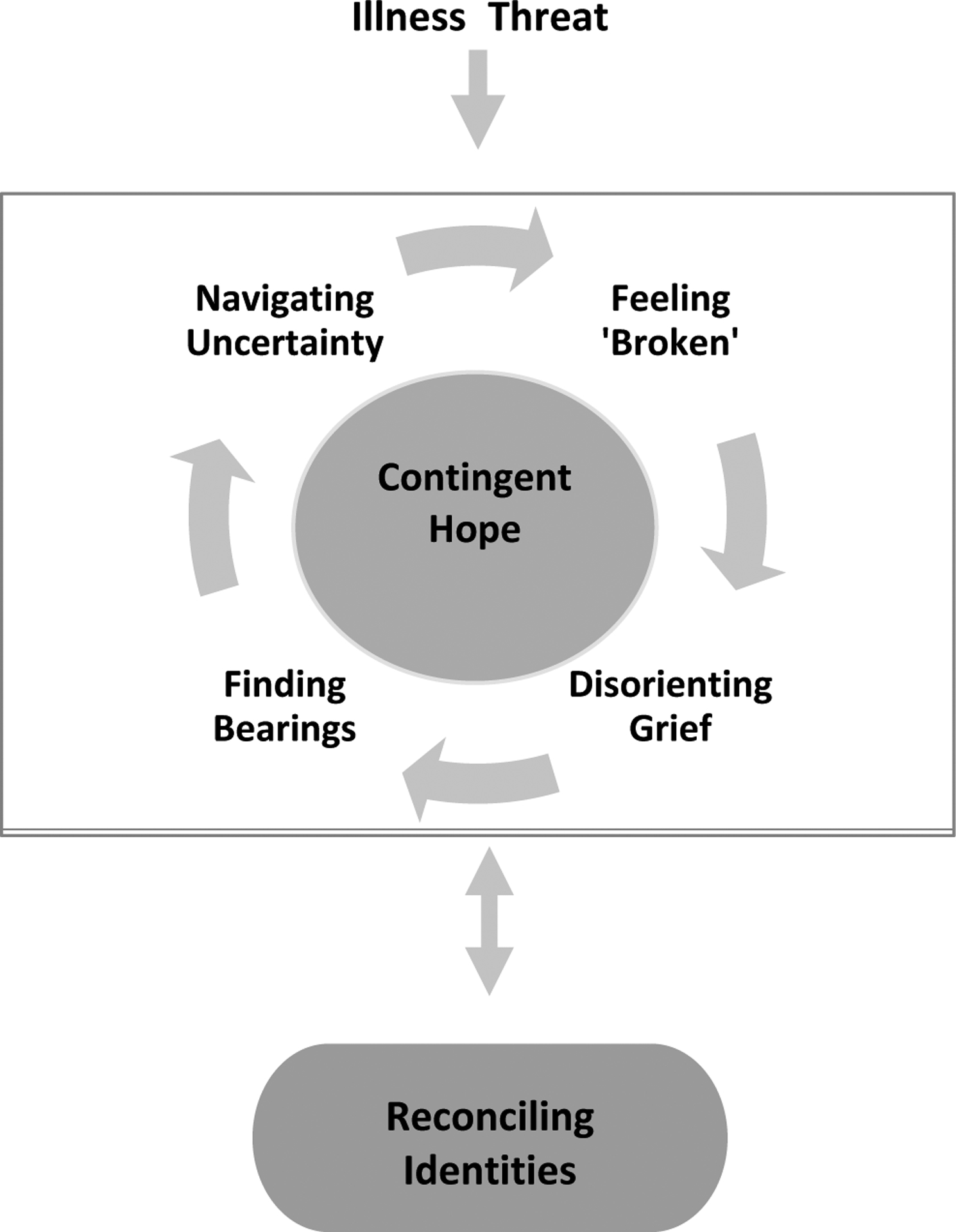

Through analysis, the research team identified contingent hope as the core category that emerged from the data. Contingent hope is defined as the motivating force that drives YAs to relieve tension resulting from their detached association with self and society. Thus, the resulting theory of contingent hope reveals the specific psychosocial processes YAs with advanced cancer engaged hope to address their detached association with self and society. The contingent hope theory includes one core category, contingent hope, and five inter-related subcategories: navigating uncertainty; feeling “broken”; disorienting grief; finding bearings; and identity reconciliation. Figure 2 conceptually presents the categories of the theory and the patterns of psychosocial processes. Hopes appeared throughout the YAs’ illness trajectories; however, the main focus of the YAs’ hopes varied based on emerging needs to relieve physical, existential, or psychosocial distress. Throughout their narratives, YAs expressed one paramount hope – identity reconciliation – the ability to reconcile cherished aspects of their pre-cancer identities with aspects of their present-day identities that bring joy and meaning. However, their ability to attain the objective of identity reconciliation depended heavily on the YAs’ addressing each of the four psychosocial processes of the contingent hope cycle, as seen in the center box in Figure 2. Contingent hope emerged as the core category as it appeared as the nucleus and main energy source for fueling each of the YAs’ ability to explore ways to regain a sense of self that felt authentic. A representation of the theory’s categories and properties appear in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Theory of Contingent Hope

Table 2.

Theoretical Framework’s Categories and Properties

| Category | Properties |

|---|---|

| Navigating uncertainty | Shattered visions of health and healthcare system |

| Advocating for care | |

| Exploring coping mechanisms | |

| Feeling broken | Body betrayal |

| Despair | |

| Internalized stigma | |

| Disorienting grief | Disorientation to all aspects of former life |

| Lost identity | |

| Isolation | |

| Finding bearings | Prioritizing health over social roles |

| Reframing goals | |

| Seeking control and autonomy | |

| Contingent hope (core) | Developing self-efficacy |

| Discovering one’s confidence | |

| Reconciling identity | Regaining trust in one’s body |

| Nurturing mutually beneficial relationships | |

| Exploring meaning & purpose |

The YAs entered the exploration of hope during illness threats at initial symptom appearance and throughout a myriad of illness challenges. Navigating the uncertainty of their illness required the development of crisis management and self-advocacy strategies. Dramatic changes in physical and psychosocial functioning rendered the YAs feeling “broken” and fearful that they might never return to their pre-cancer persona. These losses culminated in the YAs reaching a point of disorienting grief, in which virtually all familiar aspects of their pre-cancer identity vanished. The YAs began to find their bearings through taking control of their lives in and outside of treatment. The self-efficacy and confidence gained through their exploration of the four processes of the contingent hope cycle enabled the YAs to summon hope to regain an identity that felt whole, authentic, and purposeful. Feeling bolstered, the YAs tackled their preeminent hope — identity reconciliation— by integrating cherished aspects of their pre-cancer identities with their present-day values, needs, and abilities. We will describe in more detail the experience of illness threats among YAs with advanced cancer and the five inter-related subcategories of the contingent hope theory: navigating uncertainty; feeling “broken”; disorienting grief; finding bearings; and identity reconciliation

Illness Threats

Cancer presented innumerous threats throughout the YAs’ illness. Initial symptoms included unusual pains, trouble breathing, palpable masses, and months of irregular bleeding. The cancers typically took aggressive courses and for some, brought their first visions of mortality: “… they had told me I was very lucky because I came in with 98% of cancer cells, and if I would have waited it would have been fatal” (P11). Threats appeared without set patterns during initial and second-line treatments, and sometimes, as late-effects after treatment. After experiencing recurrences, fears intensified while waiting for the next treatment plan: “They said we’ll see you like in three or four weeks. And so, like the summer before, I just get the scary news and you just have to sit with it and hold it” (P02). Regardless of time on/off treatment, new symptoms triggered fears that death may be imminent. As formidable health crises arose, so too did all-encompassing uncertainty.

Navigating Uncertainty

During moments of uncertainty, regardless of treatment phase, initial hopes centered around finding the cause of suffering and formulating a plan to reduce threats to health and identity. The intrusion of advanced cancer in the prime of their lives shattered YAs’ perceptions of invincibility. Individuals blamed symptoms on excessive workouts, long hours studying or working, carrying heavy backpacks, or limited sleep. This rationalizing created a momentary safe space to cope with health uncertainty. Inevitably, each YA encountered times of feeling overwhelmed and bewildered. This jarring adjustment was described as being “Such a shock to the system to go from being a normal person to suddenly like you’re dying and everything is killing you” (P01). Coping mechanisms frequently centered on engaging distractions; clinging to “normalcy”; or suppressing difficult emotions. Avoidance, humor, movies, friendships, and nature served as healing distractions. An example of use of avoidance appeared when one YA described their hopes for the future: “I have no idea. That’s why I live such a great life. I don’t think about things [laughing]” (P07). Continued involvement with familiar activities and responsibilities evoked purpose, belonging, and hope for normalcy in an ever-changing world.

Distrust of healthcare providers and systems resonated throughout diagnoses narratives. As YAs sought care at university health centers, community clinics, and emergency rooms, they encountered barriers to access such as lack of insurance and providers who dismissed cancer symptoms due to young age. All but two received incorrect diagnoses with some waiting almost two years for cancer diagnoses. An example of frustration with providers appeared as follows: “So that was the most frustrating thing because for essentially a year and a half my cancer was just allowed to grow and grow and grow and grow” (P05). Consequently, many harbored distrust that shaded judgement during future provider interactions. Untimely diagnoses of advanced cancer left YAs feeling immense frustration, provider distrust, anxiety, and unattended suffering.

Each of the YAs explored ways to advocate for their own healthcare needs; however, since many of the YAs had limited experience with health crises, their evolution into self-advocates necessitated partnerships and practice. Initially, family members and friends assumed supporting roles in researching treatments. As self-efficacy increased, the YAs became skillful in asking questions, finding insurance, and health resources. Distressing interactions with medical providers led many YAs to become fierce self-advocates as demonstrated in this reflection: “I got to a point where if I didn’t like you I was going to go to someone else” (P03). They advocated for treatments that limited risks for second cancers, infertility, and loss of function. Mastery of healthcare systems increased hopeful mindsets for palatable treatments, sustained function, and potential to reclaim aspects of their former selves.

Feeling “Broken”

Alterations in functional abilities created feelings of body betrayal, despair, and “brokenness”. Disturbing symptoms included loss of ability to walk and speak, debilitating pain, emotional dysregulation, cognitive impairments, infertility, and incontinence. Most female participants portrayed the devastating psychosocial impacts of treatment-induced infertility like the following account: “I know I saw myself as broken because I couldn’t give him a child. That broke me the most. I felt so sad” (P12). Many described feeling betrayed by their bodies and waking each day trapped within an older person’s body. YAs internalized societal messages about differences and impairments; thus, intensifying their despair. While attending a party after starting cancer treatment, one YA quickly noticed social and physical disparities:

I felt like a glass doll. Is that what you would call it? I was breakable but also I felt like everybody else was like in the dollhouse and I was outside just looking in and observing them but not like part of their world at all

(P13).

Signs and symptoms of despair appeared as depression, panic attacks, reclusiveness, and restriction of food intake due to pain, nausea, or treatment-related taste changes. Anxiety appeared during intrusive medical procedures, scans, physical exams, or when approaching treatment centers. Four YAs (30%) encountered panic attacks that persisted up to three years post-treatment. A couple years post treatment, a YA experienced a panic attack in the following way:

I was sitting in the middle of class and suddenly had the sharp stabbing pain in my chest. I couldn’t focus. I had to run out of the room and go cry in the bathroom. I was thinking how, gosh, this is going to be my life now

(P04).

Most debilitating among the emotional sequalae of treatment were depressive symptoms often induced by physical dependence, adaptive functioning, and loss of mobility and purpose. Glaring differences between pre-cancer and present-day functioning culminated in participants feeling “broken” and fearful that they may never absolve cancer’s hold on their identity.

Disorienting Grief

Periods of feeling broken accumulated until a point when YAs lost orientation to almost every facet of their identity. Many lost fertility, faith, and stability in school, careers, relationships, and finances. YAs also lost orientation to their bodies that had previously carried them through life without fail. The injustice of cancer at this developmental time left many questioning their beliefs: “So I grew up going to church and I came to my own personal understanding of faith in high school. Then, you know, in college this happened and for a long time I really struggled with what do I actually believe. Like do I believe that God is good? If so, why did he let this bad thing happen to me? Can I trust him?” (P01). Each portrayed a disorienting state of existence where they felt out of sync, left behind, living in an altered reality, or having landed on another planet without a guidebook. YAs frequently incorporated metaphors to capture this disorienting state of loss:

Like have you ever tried to untangle Christmas lights or a giant ball of yarn with different colors? And one color is your relationships with women or men and the other one is your family, your job, your own happiness. They are all just tangled together and dropped down in front of you. The first thing you do is look at it and go what am I going to do with this?

(P06).

This disorienting state intensified feelings of difference and brokenness.

Considering the rarity of their situation, few people truly understood the magnitude of their grief. Many YAs felt abandoned by their pre-cancer peers who carried on with their lives. They also experienced isolation in treatment facilities since most patients were older or YAs receiving curative treatment. This dire sense of alienation appeared in almost every segment of YAs’ lives:

I just constantly felt like I didn’t fit in with my friends because they didn’t understand what I was going through. And then I didn’t fit in with people who did understand what I was going through because they really didn’t because they were so much older than me. And I was just stuck in this weird spot of not really knowing like which crowd to relate to or who are like my people, so to say

(P05).

Initial searches for peers with advanced cancer were exhaustive, yet futile; thus, exacerbating isolation and driving many of the YAs to further detach from society. Family members served as touch stones to the YAs’ past identities but lacked understanding of the YAs’ true suffering. Everywhere they turned for understanding, the YAs found themselves alone in grief. Few had energy, resources, or referrals for counseling; therefore, most grieved alone.

Finding Bearings

After resolving illness threats, YAs endeavored to find their bearings in uncharted territories. YAs simplified schedules by prioritizing healthcare needs above beloved social outlets. Attention to physical needs augmented hope through alleviating suffering and potentially extending life. Their new vocation entailed researching treatments, providers, YA specialized treatment centers, and strategies for managing side-effects. YAs harnessed their online research skills and connections to find specialists:

This isn’t healing, there is still something growing. That’s when I found this company, I found Driver. They are about to go public. They had a soft opening… They helped me connect with a [specialist] because we don’t have one here

(P08).

YAs travelled across the country and became experts at finding novel treatments and doctors with experience in treating their rare cancers.

YAS learned to live more simply and focused energy on activities that rendered maximum benefit with minimal energy:

Before I had cancer, I was a big saver, saving up money, saving up to do this, to do that, or you now, making sure I paid my tuition. Now I am more, I spoil myself. If I want to get ice cream that costs $15, then I will get it

(P10).

Through reframing mindsets and daily priorities, the YAs balanced lost opportunities for participation in developmental milestones with hopes for physical recovery and meaningful futures.

Controlling personal and interpersonal impacts of their illness became paramount and offered hope for reducing the traumatic impacts of cancer. As much of what they held dear slipped away, the YAs yearned for autonomy and control. Most YAs closely regulated nutritional intake, disclosure of health information, and relationship dynamics. They protected loved ones from exposure to negative prognostic information, especially those who had children. One parent feared the long-lasting impacts their death could have on their children: “I was so afraid this would shape their understanding of what God was in a way that I couldn’t control. I wouldn’t be there to walk them through that process” (P09). Parents carefully crafted legacies by planning dialogues and activities with family that nurtured positive memories, familial values, and love. YAs worked beyond physical limits to protect family members from medical debt. Through the process of finding bearings, the YAs began to regain control, autonomy, and reduced trauma for themselves and loved ones.

Core Category: Contingent Hope

YAs portrayed detached association with self and society as their main challenge in maintaining hope. They longed to feel whole and hold a valuable place in society; yet, their illness and grief overwhelmed their coping mechanisms and left many YAs feeling socially isolated, depressed, and anxious. Few of the YAs had experienced personal crises before their diagnosis; thus leaving them with limited opportunities to develop the self-efficacy instrumental in addressing their physical, psychosocial, and existential crises. Thus, as their illness quickly removed most salient aspects of their former identities, YAs began to assess their illness threats and entered into the four psychosocial processes associated with the contingent hope cycle. Their confrontation with each facet of the contingent hope cycle enabled the YAs to gather the skills and motivational energy to address their objective of identity reconciliation.

From the onset of troubling symptoms, the YAs questioned potential health ramifications and their ability to enjoy young adulthood. They quickly faced decisions about managing their life as a cancer patient while also fighting fiercely to maintain their selfhood. The disorienting nature of their losses resulted in a dwindling sense of normalcy, identity disengagement, and feeling physically, psychosocially, and spiritually broken. As each new illness threat arose, YAs entered back into the cycle of contingent hope and reflected on how each symptom or treatment might interfere with their ability to regain their authentic self. Each threat brought forth confrontation with uncertainty, brokenness, grief, and finding bearings; however, time within the cycle varied based on the perceived enormity of the threat. Through time and mastery of new threats, YAs began to acknowledge their strength, courage, and ability to reframe most challenges they encountered:

Because I started and one level and you know, you get all these obstacles and I went through all of this and you kind of see the light at the end of the tunnel. As you get closer, you get more hopeful like this is going to be over. Yes, I can overcome things. After talking about my story so many times, I realize that I am a stronger person than I thought I was. Through this incremental cultivation of courage and self-efficacy, YAs nurtured hope that they could craft a fulfilling future by moving forward with their identity reconciliation.

Identity Reconciliation

With increased exposure to health instability, participants became more agile in managing distress and exploring resources to reclaim their bodies, minds, faith, and relationships with loved ones. society. They became ready to venture into the exploration of identity reconciliation. The initial step in reconciling identities involved finding peace with body mistrust, disgust, hatred, and sometimes, dissociation:

Like your love for yourself sometimes goes up and down depending on how you are feeling; sometimes I hate myself, like why did this have to happen to me. But like with hope, you know it’s always that glimmer of you know, it can be better, and can get better

(P08).

Finding a place of comfort with their bodies took time, Herculean effort, personal reflection, interpersonal dialogues, and the poignant realization that to move forward, they must find ways to trust their bodies. Participation in YA retreats offered “… healing and felt really good just to like challenge [the] body like that and get back in touch with it, and be in nature, and be with other young adult survivors” (P01). Since most of their despair resulted from functional disruptions in carrying out roles, by reframing abilities, they experienced increased confidence in achieving goals, and hope for fulfilling futures.

Reclaiming one’s emotional well-being became essential. Frequently, YAs pushed through treatment and had limited energy to focus on mental health. Family and friends became sounding boards; however, the YAs typically held deep emotions close. The vast impacts of their illness created overwhelming grief, depression, and anxiety. Several YAs described symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, such as intrusive disturbing memories of physical and psychological treatment reactions; detachment from one’s former interests and others; and hypervigilance surrounding one’s eating habits and behaviors that may increase risks of cancer’s spread. Some postponed counseling until after completion of initial treatment because they feared opening Pandora’s box while symptoms peaked. Time in counseling resonated as one of the most hopeful steps towards reconciling identities. Therapists provided tools for survivors to reframe the challenges of their illness:

This is the point where I started really thinking more about meditation, about the idea of… like the things you do to fight the suffering make the suffering worse. And instead, like I just need to surrender myself to it and feel and that will be better

(P02).

Counselors offered validation, safe spaces to share secret fears, and guidance on creative outlets to address grief and rekindle their authentic self. A few described venturing into a healing spiritual journey and discovered ways in which prayer, organized religion, faith in higher beings, nature, and pets fostered comfort and peace.

Cultivating relationships inside and out of the cancer community nurtured connection, love, and personal/societal value. Discovering YA cancer peers offered a community of shared identity dissonance. Peers with advanced cancer reduced the burden of feeling like a case study; yet, increased exposure to death and survival guilt. Fruitful relationships developed through work, college, volunteer activities, and faith communities. Friendships outside of cancer provided opportunities to share one’s multifaceted identity beyond someone who has/had cancer.

Cancer tested many of the participants’ intimate relationships. Those who were married at the time of diagnosis maintained their relationships but often encountered challenges in physical intimacy due to fatigue, hormonal and steroid-induced changes, body image concerns, and compromised immune systems. Couples worked together to discover ways to overcome challenges and a few stated that cancer nourished bonds. Those dating during cancer encountered many challenges, such as when becoming acquainted with potential partners:

Half were like, I don’t want to put you through this I don’t want to break your heart because [you] had cancer. The other half were like I know, I understand what you are going through, I can support you if you ever need anything. But then also, the half that supported me kind of, I want to say that half of them kind of felt sorry

(P10).

A few of the YAs remained on an arduous journey to find loving and understanding partners.

Existential quests appeared commonly in narratives and provided meaning for undue suffering and hope for purposeful reintegration into society. All the YAs found cancer as an awakening and impetus to explore the meaning of their life and personal suffering. Several determined their purpose was to mentor others experiencing life challenges and changed their vocation or educational focus. This poignant epiphany appeared for one YA after meeting other YAs at a CancerCon conference:

I want to let other young adult cancer patients know that they are not alone that there are other people going through it. That they aren’t special… they are a special case, they aren’t special. Because you don’t want to feel special because being special means you don’t know what is going to happen. Being special means I don’t know how long you have; I don’t know how this is going to play out. If you aren’t alone then you think, I am going to be okay

(P10).

When not physically able to work, YAs found rewarding volunteer roles at cancer foundations, treatment centers, schools, and children’s welfare organizations. They created cancer awareness walks, Facebook pages, and mentored other YA survivors. One YA shared their passion to help others: “I was like, let’s start a group where it doesn’t have to be so formal and we can just talk to each other and meet and share. I started a group called [xxx]. It was just like 12 of us and now it’s 137 people” (P12). The YAs frequently integrated a positive lens to the suffering they endured and credited mentoring cancer peers as providing hope to fulfill their unexpected life missions.

YAs reconciled their cancer identities in ways that offered the most personal and/or societal meaning. Most embodied the role of cancer survivor, advocate, and mentor; although few purposefully crafted lives where cancer played a minimal role. Choosing the voice cancer played in their narrative offered YAs the opportunity to fulfill their ultimate hope of shaping an identity that felt whole again. They acknowledged and grieved their lives pre-cancer and explored ways in which their present identity provided meaning, joy, and fulfillment.

Discussion:

The theory of contingent hope provides novel insight into the psychosocial processes that YAs with advanced cancer employ to maintain hope during their life-limiting illness. Overwhelming symptom burdens frequently incited depression, anxiety, body betrayal, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress (Jones et al., 2011; Knox et al., 2017; Rosenberg & Wolfe, 2013). Cancer left the YAs feeling developmentally arrested (Knox et al., 2017) with identities that centered on being a cancer patient (Linebarger et al., 2014). They had to make numerous cognitive shifts to bear the untimely physical and psychosocial sequelae typically experienced by older adults at the end-of-life. The compounding losses experienced by the YAs resulted in disorienting grief in which the YAs become estranged from all aspects of their former lives (Malone et al., 2011). Research examining the lived experiences of adults with advanced lung cancer (Roulston et al. 2018), reveals similar feelings of betrayal and lost faith due to medical providers’ delays in diagnosing cancer. The narratives of this study’s participants also shared Frank’s (1995) narrative structures of restitution, chaos and quest. There is a “biographical disruption” (Bury, 1982) in which cancer disrupts plans and hopes for the future. In the chaos narratives, patients describe emotional struggles, symptom burden and the impacts of their advanced cancer on body image, social relationships and roles. In the quest narratives, patients reflect upon their illness journey and want to share their story with others, consistent with our finding of higher level existential processing to foster meaning making and identity reconciliation.

The exploration of the motivating forces of hope reached popularity in the 1980’s within the fields of philosophy, health psychology, and spirituality. Since that time, researchers have strived to bring more clarity to the “elusive, mysterious, and soft” (Farran, Herth, & Popovich, 1995, p. 5) nature of hope. Numerous definitions and frameworks exist each portraying unique conceptual structures of hope. Most hope theories incorporate aspects of goal attainment (Dufault & Martocchio, 1985; Farran, Herth, & Popovich, 1995; Snyder, 2002), while hope theories within palliative care settings embrace the additional focus of constructing meaning amidst overwhelming uncertainty (Herth & Cutcliffe, 2002; Nekoliachuk & Bruera, 1998). This study offers insight into the concrete functions of hope and extends Snyder’s (2002) work by describing how the confidence, self-efficacy, and courage garnered through navigating the psychosocial processes of the contingent hope cycle enhance one’s ability to reframe hopes and one’s physical and psychosocial-spiritual agency and pathways to attain goals. Additionally, this theoretical perspective of hope reveals a unique developmental context of hope by portraying the motivating forces of young adult identity development and the reconciliation of pre-cancer goals with present-day existential quests for finding purpose and meaning.

In the context of decision-making among AYAs with late-stage cancer (Figueroa Gray et al., 2018), there is concurrence that YAs balance their hopes against the risks of their continued treatment. The activation of the contingent hope cycle enabled YAs to attain self-efficacy in managing their physical and psychological needs such that they could engage a higher-level of existential processing that facilitated the exploration of meaning and reconciliation of identities. YAs’ self-identities evolved during their illness experience and they endorsed quests for meaning, purpose, and/or legacy (Barton et al., 2018). Their hard-earned grit provided motivation to integrate cherished aspects of their pre-cancer identities with their new set of world beliefs (Lethborg et al., 2006). Subsequently stimulating hope and motivation to construct a meaningful life and legacy.

Limitations

Although this study offers many strengths, a few limitations emerged. This study includes a sample with strong social support networks; ability to perform many activities of daily living; and with limited ethnic/cultural diversity. Extended exposure to an inclusive sample of YAs with advanced cancer at multiple times throughout their illness trajectory might provide further insight into potential changes in hope engagement. These findings may reflect selection bias by highlighting experiences of YAs who see benefit in cultivating hope. Additionally, due to the structured nature of the interviews, these findings may represent an altered dynamic of hope from how YAs naturally discuss hope.

Clinical Implications

Clinical implications from this study center on the implementation of interprofessional dialogues and psychosocial interventions that address the unique influential pull of young adulthood on the ability to maintain hope while living with advanced cancer. YAs want support facing mortality (Figuero Gray et al., 2018). Palliative care and oncology teams can partner with YAs to discuss and explore symptom burden, body betrayal, despair, grief, and barriers to goal attainment. Open communication eliciting patient values can help to enhance feelings of mutual respect between YAs and providers and promote discussion of existential quality of life and identity reconciliation. Since most YAs carried the emotional burden of their illness in isolation, peer support programs may foster social connection and help to reduce the devastating impacts of disorienting grief. Using the NIH Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development (Onken et al., 2014), this research describes the psychosocial processes that YAs with advanced cancer employ to cope with their life-limiting illness. Future stage I research can examine and test novel behavioral intervention strategies and clinical tools to holistically support YAs living with advanced cancer.

In conclusion, YAs living with advanced cancer hold fiercely to their budding sense of independence and developmental achievements. Their narratives highlight significant psychosocial and existential distress, which due to the disorienting nature of their losses, YAs typically endured alone. The contingent hope theoretical framework provides concrete psychosocial behavioral patterns that YAs engage to foster hopefulness. Through partnerships with their interprofessional care teams, YAs can gather the fundamental skills and resources to kindle hope for futures that fuel their purpose, passion, and connection to society.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the young adult participants for sharing their experiences of hope and for their unanimous passion to enhance the well-being of other YAs with advanced cancer. J.C-M. was supported by a Doctoral Training Grant in Oncology Social Work Renewal, DSWR-18-087-03, from the American Cancer Society and a PEO Scholar Award. C.W. is currently supported by an NIH/NCI 5T32 CA092408.

Appendix A: Interview Guide

Thank you for willingness to meet with me today. I appreciate you sharing your time to talk with me about your diagnosis and what life has been like since that first day. There may be times when you get tired or would like a pause. Please let me know and we can take a break.

OPENING QUESTION:

I would like to start our time together today talking about the time when you were diagnosed with cancer. Can you take me back to the time when you were diagnosed and what you experienced and were feeling and thinking?

First set of probes: Time of diagnosis

Events, experiences, actions

Feelings

Thoughts

Directions for constructing your hope trajectory:

On this piece of paper, I would like for you to share your own unique story of hope. You can draw hope however you would like. Please mark pivotal moments in your hope timeline where your hope changed, or memorable things happened to you along your cancer journey.

Second set of probes: Hope Timeline

DIRECTIONS:

Use the timeline to point specific time periods along the participant’s hope trajectory to facilitate recall.

Many young adults describe this motivating force as hope. Does this resonate with you? What does hope mean to you?

Story past:

How has hope changed for you since you found out about the cancer?

What were you hoping for at that time of diagnosis? (goals)

I see that your level of hope is (the same or different) from your time of diagnosis. Please you tell me about this?

During your illness, tell me about the times that you’ve felt most hopeful.

Now tell me about the times that made you feel least hopeful.

Story present:

What does hope mean to you now?

What helps you maintain hope? (Who, what, where?)

At this point are there specific things you are feeling hopeful about?

Story future:

Do you have specific plans or goals that you want to accomplish?

References

- American Cancer Society (2018). What are the key statistics for cancers in young adults? Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-in-young-adults/key-statistics.html

- Bally JMG, Duggleby W, Holtslander, et al. (2014). Keeping hope possible: A grounded theory study of the hope experience of parental caregivers who have children in treatment for cancer. Cancer Nursing, 37(5), 363–372. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182a453aa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton KS, Tate T, Lau N, et al. (2018). ‘I’m not a spiritual person’: How hope might facilitate conversations about spirituality among teens and young adults with cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(6), 1599–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin, et al. (2000). Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284(22), 2907–2911. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M (1982). ‘Chronic illness as biographical disruption’. Sociology of Health and Illness, 4(2), pp. 167–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt CM (2011). Hope in adults with cancer: State of the science. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38(5), E341–E350. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E341-E350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov H, Wilson K, Enns, et al. (1998). Depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics, 39(4), 366–370. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(98)71325-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JK and Fasciano K (2015). Young adult palliative care: Challenges and opportunities. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 32(1), 101–111. doi: 10.1177/1049909113510394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufault K, & Martocchio B (1985). Hope: Its spheres and dimensions. Nursing Clinics of North America, 20(2), 379–391. Retrieved from https://europepmc.org/abstract/med/3846980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby W (2000). Enduring suffering: A grounded theory analysis of the pain experience of elderly hospice patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 27(5), 825–831. Retrieved from https://europepmc.org/abstract/med/10868393 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby W and Wright K (2009). Transforming hope: How elderly palliative patients live with hope. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 41(1), 204–217. Retrieved from http://cjnr.archive.mcgill.ca/article/viewFile/1944/1938 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1950). Childhood and Society. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Farran CJ, Herth KA, Popovich JM (1995). Hope and hopelessness: Critical clinical constructs. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa Gray M, Ludman EJ, Beatty T, et al. (2018). Balancing hope and risk among adolescent and young adult cancer patients with late-stage cancer: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 7(6), 673–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A (1995). The wounded storyteller: Body, illness, and ethics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG and Strauss AL (1967). The discovering of grounded theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG (1978). Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herth KA, & Cutcliffe JR (2002). The concept of hope in nursing 3: Hope and palliative care nursing. British Journal of Nursing, 11(14), 977–983. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2002.11.14.10470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtslander LF and Duggleby WD (2009). The hope experience of older bereaved women who cared for a spouse with terminal cancer. Qualitative Health Research, 19(3), 388–400. doi: 10.1177/1049732308329682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison ED (2015). Dimensions of human behavior: Person and environment (Fifth ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. (2013). SPSS statistics for windows. Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jones B, Parker-Raley J, Barczyk A (2011). Adolescent cancer survivors: Identity paradox and the need to belong. Qualitative Health Research. 21 (8) 1033–1040. doi: 10.1177/104973231140029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent EE, Parry C, Montoya, et al. (2012). “You’re too young for this”: Adolescent and young adults’ perspectives on cancer survivorship. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 30(2), 260–279. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.644396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox MK, Hales S, Nissim R, et al. (2017). Lost and stranded: The experience of younger adults with advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(2), 399–407. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3415-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam WW, Yeo W, Suen J, et al. (2016). Goal adjustment influence on psychological well-being following advanced breast cancer diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology, 25(1), 58–65. doi: 10.1002/pon.3871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V (2008). The existential plight of cancer: Meaning making as a concrete approach to the intangible search for meaning. Supportive Care in Cancer, 16, 779–785. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0396-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lethborg C, Aranda S, Bloch S, et al. (2006). The role of meaning in advanced cancer: Integrating the constructs of assumptive world, sense of coherence, and meaning-based coping. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 24(1), 27–42. doi: 10.1200/J077v24n01_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linebarger JS, Ajayi TA, Jones BL (2014). Adolescents and young adults with life-threatening illness: Special considerations, transitions in care, and the role of pediatric palliative care. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 61(4), 785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone P, Pomeroy E, Jones B (2011). Disoriented grief: A lens through which to view the experiences of Katrina evacuees. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care. 7:241–262. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2001.593159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S, Grinyer A, Limmer M (2018). Dual liminality: A framework for conceptualizing the experience of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 8(1), 26–31. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2018.0030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Tsilika E, et al. (2008). Preparatory grief, psychological distress and hopelessness in advanced cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer Care, 17(2), 145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365.2354.2007.00825.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekolaichuk CL, & Breuera E (1998). On the nature of hope in palliative care. Journal of Palliative Care, 14(1), 36–42. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/openview/da6b00e7f83bd2c1579eabc86699ba3d/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=31334 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissim R (2008). In the land of the living/dying: A longitudinal qualitative study on the experience of individuals with fatal cancer. (Doctoral Dissertation, York University). [Google Scholar]

- Onken L, Carroll K, Shoham V, et al. (2014). Reenvisioning clinical science: Unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penz K and Duggleby W (2011). Harmonizing hope: A grounded theory study of the experience of hope of registered nurses who provide palliative care in community settings. Palliative and Supportive Care, 9(3), 281–294. doi: 10.1017/S147895151100023X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard S, Cuvelier G, Harlos M, et al. (2011). Palliative care in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer, 117(S10), 2323–2328. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg A and Wolfe J (2013). Palliative care for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Clinical Oncology in Adolescents and Young Adults, 3, 41–48. doi: 10.2147/COAYA.S29757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulston A, Davidson G, Kernohan G, et al. (2018). Living with life-limiting illness: Exploring the narratives of patients with advanced lung cancer and identifying how social workers can address their psycho-social needs. British Journal of Social Work, 48(7), 2114–2131. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcx147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs E, Kolva E, Pessin H, et al. (2013). On sinking and swimming: The dialectic of hope, hopelessness, and acceptance in terminal cancer. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 30(2), 121–127. doi: 10.1177/1049909112445371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snöbohm C, Friedrichsen M, Heiwe S (2010). Experiencing one’s body after a diagnosis of cancer—a phenomenological study of young adults. Psycho-Oncology, 19(8), 863–869. doi: 10.1001/pon.1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevino KM, Abbott CH, Fisch MJ, et al. (2014). Patient oncologist alliance as protection against suicidal ideation in young adults with advanced cancer. Cancer, 120(15), 2272–2281. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERBI Software. (2018). MAXQDA analytics pro. Berlin: Germany: VERBI. [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack B (2011). Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer, 117(10 suppl), 2289–94. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]