Abstract

Therapeutic alliance may influence treatment outcomes for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The present study examined the trajectory of alliance, observationally-measured at four timepoints during a 16-week mindfulness-based treatment targeting emotion regulation problems in adolescents and young adults with ASD (n = 37, mean age = 15.28, 78.40% male). Variability in alliance as a function of client characteristics and the degree to which alliance predicted emotion regulation outcomes were assessed using parent-report forms. Results demonstrate that alliance fluctuates throughout treatment. Moreover, stronger alliance predicts decreased dysphoria at posttreatment. Results also suggest that increased ASD symptom severity and depression predict weaker alliance early and throughout treatment. Findings highlight a need for clinicians to consider the importance of developing strong alliance for clients with ASD.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Therapeutic alliance, Adolescents, Adults, Emotion regulation, Treatment outcomes

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that occurs in about 1 in 54 children (Maenner et al. 2020). It is characterized by impairments in social communication and restricted and repetitive interests (APA 2013). Individuals with ASD often experience difficulties with emotion regulation (ER; Mazefsky et al. 2014; Patel et al. 2017; Samson et al. 2012, 2015), which can exacerbate impairments in social functioning and contribute to secondary psychiatric problems (Mazefsky and White 2014). Impairment in ER is associated with a host of emotional and behavioral problems for individuals with ASD, including anxiety, depression, and aggression (Conner et al. 2020; Mazefsky et al. 2014; Patel et al. 2017; Pouw et al. 2013; Schäfer et al. 2017), such that poor ER has been implicated as a potential pathway for co-occurring psychiatric disorders (Conner et al. 2020). Thus, targeting ER as a transdiagnostic factor may be ideal for intervention efforts (Weiss 2014). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are two promising treatments for targeting ER difficulties for individuals with ASD (Cachia et al. 2016; Conner et al. 2019; Conner and White 2018; Gu et al. 2015; Holzel et al. 2011; Kiep et al. 2015; Thomson et al. 2015; Weiss et al. 2018). While these specific treatment approaches have shown promising results in improving ER for individuals with ASD, little research has identified factors in the therapeutic process that lead to successful outcomes.

The therapeutic alliance, or the collaborative relationship between the client and therapist, has been identified as predictive of better treatment outcomes for youth and adults without ASD in a variety of behavioral and nonbehavioral treatments (Flückiger et al. 2018; Karver et al. 2018; Shirk and Karver 2003, 2011). Alliance is considered particularly crucial for adolescents since they are often brought to therapy by their parents’ choosing and may be neither aware of their problems nor motivated to receive help (Shirk and Karver 2003). Therapeutic alliance is comprised of three elements: task (the client’s willingness to talk with the therapist and participate in therapy activities), bond (the affective relationship between the client and therapist), and goal (the agreement in treatment goals; Bordin 1979). The combination of these three elements determine the strength and quality of the alliance (Bordin 1979). However, client characteristics, such as cognitive ability (Kazdin and Durbin 2012) and symptom profile (e.g., anxiety, depression, oppositional behavior, or ADHD; Zorzella et al. 2015) can also impact the strength of therapeutic alliance.

Much of the literature on alliance has relied on self- or therapist-rated alliance, which is often reported on at the end of treatment. Although therapy is undoubtedly a subjective experience that is important, there are factors that bias how therapists and clients rate alliance, such as a desire to be well-liked (Accurso and Garland 2015; Shirk and Karver 2003; Shirk and Saiz 1992). Furthermore, youth clients can have limited variability in their self-reports on alliance, possibly because of limited insight into the therapeutic process or wanting to be liked by the therapist (Shirk and Saiz 1992). This is a particular problem for youth with ASD who tend to have difficulties with insight into their own experiences and symptoms (Mazefsky et al. 2011; Pearl et al. 2017; White et al. 2012). Observational techniques, which require rigorous coding using in-session evidence and examples of alliance, offer a more objective methodological approach to characterizing alliance for clients with ASD. Therapeutic alliance is dynamic and, as such, can fluctuate within an individual session and throughout the course of treatment (Chu et al. 2014). Observational coding at multiple timepoints can be used to capture subtle temporal changes over the course of treatment, which post hoc client or therapist ratings cannot. Additionally, observational assessments consider the session holistically, and are likely less prone to memory and recency effects (e.g., how the session ended).

The extant research on alliance in therapy with clients with ASD is sparse. One study identified that children with ASD had significantly weaker alliance with their therapists per child- and therapist-report than their typically developing peers in treatment (Klebanoff et al. 2019). To the authors’ knowledge, three studies that examine the therapeutic alliance in relation to treatment outcomes in ASD have been published. These studies mainly used self-report measures from individuals involved with the therapeutic process and focused solely on children under the age of 16 (Kerns et al. 2018; Klebanoff et al. 2019). Across studies, therapist-reported alliance was negatively associated with anxiety treatment outcomes, such that stronger alliance was related to decreased anxiety at posttreatment for children with ASD (Kerns et al. 2018; Klebanoff et al. 2019); child-reported or parent-reported alliance was not associated with treatment outcomes. These findings reflect non-ASD literature suggesting that therapist-rated alliance is more related to posttreatment outcomes (Shirk and Karver 2003).

Although research suggests that alliance can be reliably measured for clients with ASD using observational coding (Burnham Riosa et al. 2019), only one study has examined the alliance—outcome relationship using an observational measure of alliance (Albaum et al. 2020). Rather than examining alliance as a whole construct, they examined task collaboration and client—therapist bond (the task and bond facets of alliance, respectively) at early and late treatment stages in relation to ER improvement for their child clients with ASD. They found that higher task collaboration measured late in treatment predicted better ER at posttreatment after controlling for baseline ER and days in treatment (Albaum et al. 2020). Although this study provides valuable information on specific components of alliance, it may be that alliance measurement later in treatment is influenced by symptom improvement (Shirk and Karver 2011). Likewise, research suggests that alliance is an unidimensional construct (Fjermestad et al. 2012); thus, studies analyzing alliance as a whole, rather than specific components, are needed.

The current study used a well-established and validated observational measure (Mcleod et al. 2017; Shelef and Diamond 2008) to characterize therapeutic alliance at multiple points in treatment and examine the relationship between alliance and treatment outcome for adolescents and young adults with ASD. Our first aim was to determine if alliance strength changed over the course of treatment. Second, we sought to determine if alliance strength was predictive of ER treatment outcomes. Our third aim was to determine if specific client characteristics predicted alliance strength. Since this is the first study to statistically examine the trajectory of therapeutic alliance across more than two timepoints for clients with ASD, no a priori hypotheses about course of alliance were made. For Aim 2, we hypothesized that strong alliance would predict better posttreatment ER outcomes. For Aim 3, it was hypothesized that age and IQ would positively predict alliance, whereas ASD severity and severity of co-occurring symptomology (e.g., depression, anxiety, and ADHD symptoms) would negatively predict alliance.

Method

Participants

Participants were 37 treatment-seeking adolescents and young adults aged 12 to 21 years old (mean age = 15.27 years, 78.40% male) and their primary caregivers. All participants lived at home with the primary caregiver who referred the participant to the study and reported on the participant’s ER difficulties and co-occurring symptomology. Participants were recruited as part of a completed open trial and ongoing larger randomized controlled trial examining the effectiveness of an intervention to improve ER skills for adolescents and young adults with ASD (Conner et al. 2019). Inclusion criteria included having (1) a diagnosis of ASD, verified by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (Lord et al. 2012) and (2) average or higher verbal intellectual ability. Exclusion criteria included (1) having a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, (2) demonstrating an immediate concern of suicidality, or (3) receiving concurrent treatment for ER problems that was determined to be redundant with the treatment used in the intervention study. All participants’ parents and participants aged 18 years or older provided written consent to participate in the study; participants aged 14–17 provided assent. Recruitment sources include referrals from ASD clinics, flyers at medical offices and schools, and a registry of people who previously participated in studies with the researchers. See Table 1 for participants’ demographic information.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n = 37)

| n (%) | |

| Sex (male) | 29 (78.40) |

| Race | |

| White | 29 (78.40) |

| Black/African American | 3 (8.10) |

| Asian | 2 (5.40) |

| Multiple races | 3 (8.10) |

| Annual household income | |

| Less than $35,999 | 3 (8.30) |

| $36,000 to $65,999 | 14 (38.90) |

| $66,000 to 100,999 | 8 (22.20) |

| More than $101,000 | 11 (30.50) |

| Site location | |

| University of Pittsburgh | 23 (62.20) |

| Virginia Tech | 7 (18.90) |

| University of Alabama | 7 (18.90) |

| Therapist sex (male) | 4 (10.80) |

| Therapist educationa | |

| Pre-masters clinician | 2 (5.40) |

| Masters level clinician | 26 (70.30) |

| PhD level clinician | 9 (24.30) |

| M (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 15.28 (2.21) |

| Full-scale IQ | 103.31 (17.13) |

| Pre-Tx dysphoria T-score | 55.41 (7.80) |

| Pre-Tx reactivity T-score | 52.01 (7.54) |

| SRS-2 total T-score | 77.14 (8.66) |

| ASEBA Parent-Report | |

| Anxiety T-scores | 69.47 (11.19) |

| Depression T-scores | 68.69 (9.13) |

| ADHD T-scores | 67.00 (9.18) |

Pre-Tx pre-treatment, ASEBA Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment, ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Information on clinicians’ education level was based on percentage of cases with a clinician with the specific education level, not the percentage of clinicians of that education level regardless of the number of cases they worked with

Treatment

The emotion awareness and skills enhancement (EASE) program (Conner et al. 2019; Mazefsky et al. 2020) is a 16-week, individual psychotherapeutic intervention to treat ER difficulties in adolescents and adults with ASD. It follows a MBI theoretical framework that incorporates mindfulness strategies (e.g., emotional awareness and acceptance, mindfulness practices), as well as cognitive strategies from CBT (e.g., cognitive reappraisal, distraction). The EASE program was developed as a transdiagnostic approach to improving ER in adolescents and young adults with ASD. EASE targets improved awareness and management of various manifestations of ER difficulties, regardless of psychiatric profile (e.g., symptoms of anxiety, depression, or irritability). After identifying clients’ individual goals related to ER, sessions proceed within four sequential modules: emotional awareness, breathing, changing how individuals relate to their thoughts, and distraction. The manual also outlines each weekly session by providing specific session objectives, mindfulness practices, and discussion topics. The program’s 16 sessions are each 45 to 60 min long. For complete information on EASE, see (Conner et al. 2019; Mazefsky et al. 2020).

A participant worked with one therapist for the entire intervention, and all therapists were supervised by an on-site licensed clinical psychologist. Therapists (n = 15; 86.67% female) included 3 clinical psychologists, 1 post-doctoral fellow, 2 master’s level clinicians, and 9 clinical psychology graduate students. Therapists rated their weekly sessions for fidelity with the manual, and the psychologists supervising them reviewed these ratings to ensure that therapists were adhering to the manual similarly across participants and sites.

Measures

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL)

The CBCL (for participants aged 6–18 years old; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001) and ABCL (for participants aged 18–21 years old; Achenbach and Rescorla 2003) are widely-used parent-report measures of emotional, behavioral, and social problems. Both measures have demonstrated good reliability and validity (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001, 2003). T-scores from the Anxiety Problems, Depressive Problems, and ADHD Problems subscales were utilized as measures of participants’ co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems.

Emotion Dysregulation Inventory (EDI)

The EDI (Mazefsky et al. 2018) is a 30-item questionnaire that parents completed about the frequency and intensity of their children’s ER difficulties. The EDI provides T-scores for two measures of ER: level of dysphoria, characterized by low positive affect/motivation and a sad or nervous presentation, and level of reactivity, characterized by rapidly escalating and poorly regulated negative emotional reactions. Higher scores reflected higher severity of ER impairment (and thus, more dysregulation). T-score conversions were completed based on norms generated from a sample of 1755 youth with ASD (e.g., “autism norms”). Parents completed the EDI at pretreatment (i.e., within 2 weeks of starting EASE) and posttreatment (i.e., within 2 weeks of ending EASE), which was used to measure treatment outcome. Parent-report, as opposed to self-report, was used given previous literature highlighting that adolescents with ASD tend to under-report their emotional and behavioral problems (Mazefsky et al. 2011; White et al. 2012). The EDI has shown good construct validity and sensitivity to change (Mazefsky et al. 2018). In the current study, internal consistency was good for both dysphoria (pretreatment α = 0.83; posttreatment α = 0.90) and reactivity scales (pretreatment α = 0.95; posttreatment α = 0.95).

Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2)

The SRS-2 (Constantino and Gruber 2012) is a 65-item parent-report that measures facets of individuals’ social abilities, including social awareness, cognition, communication and motivation, as well as individuals’ restricted and repetitive behaviors. The Total T-score was used as a measure of ASD severity.

Vanderbilt Therapeutic Alliance Scales Revised, Short Form (VTAS-R-SF)

The VTAS-R-SF (Shelef and Diamond 2008) is an observational measure of therapeutic alliance. It is comprised of five items rated using a 6-point Likert-type scale that measure perceived support and trust, level of participation, and agreement on the client’s presenting problems and session goals and tasks between the client and therapist. Higher total scores reflect stronger alliance. The VTAS-R-SF has high internal consistency (α = 0.90) and predictive validity using a sample of adolescents with substance abuse problems (Shelef and Diamond 2008). It also demonstrates good convergent validity with other alliance measures (Mcleod et al. 2017). Additionally, as an observational measure, it should be free of response bias and developmental limitations that have been associated with self-report (Berthoz et al. 2005; Shirk and Karver 2003).

Alliance was rated using videotapes of participants’ therapy sessions. Participants’ 16 sessions were divided into four stages that approximately correspond to the program’s 4 modules: Time 1 (sessions 1–4: Awareness), Time 2 (sessions 5–8: Breathing), Time 3 (sessions 9–12: Change), and Time 4 (sessions 13–16: Distraction). A videotape from each of the timepoints was randomly selected and coded for alliance, excluding the first and last sessions. Thus, each participant had four videotapes coded. Total alliance strength at the four timepoints and an overall mean alliance score (average of the four timepoints) were used.

The coding team consisted of a master coder and three undergraduate research assistants. Reliability with the master coder was achieved after three consecutive videos with ≥ 80% agreement (exact agreement on 4 out of 5 items; Cicchetti and Sparrow 1981). After becoming reliable, the coders independently coded remaining sessions (n = 148), and the master coder co-coded a random sample of 20% of sessions (n = 30) to maintain reliability. Coders were not blind to the session number they were coding, although precautions were taken to avoid coder bias. Specifically, coders watched and reviewed tapes in random order; also, they did not code the same participant or the same section of treatment twice in a row. In order to protect participants’ confidentiality, coders watched and rated sessions using a password-protected online platform in a private location and did not have access to clients’ personal information or other study data. To avoid coder drift, the coding team met twice per month to discuss the sessions double-coded for reliability. If disagreements in ratings occurred, then the coding team discussed applicable item criteria until they agreed on a consensus code.

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition (WASI-II)

The WASI-II (Wechsler 2011) is a measure of cognitive abilities in individuals aged 6 to 89 years. The Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ-4) is a composite of cognitive abilities derived from the four WASI-II subtests and was used as a measure of overall cognitive abilities in the current study.

Data Analytic Plan

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24 (IBM Corp. 2017). Prior to analyses, data were checked for all assumptions. Missing data was minimal and participants with missing data were excluded from analyses using that specific data. Alliance scores were also checked to ensure that there were no differences in alliance strength based on the videotaped session selected, coder of the session, or any therapist characteristics. No statistical differences were found. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics and Table 2 for correlations between main study variables.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations between demographic and main study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Age | – | ||||||||||||

| (2) Gender | .14 | – | |||||||||||

| (3) FSIQ-4 | −.05 | .27 | – | ||||||||||

| (4) Mean alliance | .05 | .18 | .13 | ||||||||||

| (5) Time 1 alliance | −.11 | .16 | .13 | .73** | |||||||||

| (6) Time 2 alliance | .14 | .04 | .01 | .72** | .30 | ||||||||

| (7) Time 3 alliance | −.03 | .11 | .18 | .85* | .55** | .53** | |||||||

| (8) Time 4 alliance | .13 | .25 | .08 | .70** | .41* | .25 | .48* | ||||||

| (9) Post dysphoria | .01 | −.11 | −.23 | −.43* | −.53** | −.04 | −.60** | −.18 | |||||

| (10) Post reactivity | −.15 | −.24 | −.27 | −.21 | −.36* | .06 | −.31 | −.07 | .73** | ||||

| (11) Anxiety | −.24 | −.02 | −.04 | −.09 | −.07 | −.24 | −.13 | .22 | .21 | .23 | |||

| (12) Depression | .03 | .11 | .01 | −.34* | −.30 | −.27 | −.30 | .01 | .40* | .18 | .53** | ||

| (13) ADHD | .02 | .04 | −.07 | .01 | .05 | −.16 | −.09 | .24 | .01 | −.02 | .43* | .23 | |

| (14) ASD severity | −.11 | .13 | −.21 | −.31 | −.29 | −.16 | −.28 | −.06 | .17 | .08 | .31 | .22 | .33* |

FSIQ-4 Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient-Four Subtest, ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ASD autism spectrum disorder

p < .05

p < .001

For Aim 1, a series of one-way repeated measures analysis of variances (ANOVAs) were conducted to determine whether there were differences in alliance strength across four timepoints in treatment. For Aim 2, a series of hierarchical multiple regressions were utilized to test the hypothesis that stronger alliance would predict better treatment outcomes. The first two models focused on whether clients’ mean alliance, averaged across all four timepoints, predicted posttreatment EDI outcomes (one model for dysphoria and one model for reactivity as a treatment outcome). The second two regression models (one for dysphoria and one for reactivity) used alliance scores at the specific timepoints to predict outcomes. Given high collinearity between Time 3 and all other timepoints, Time 2 and Time 3 were averaged together to create a new variable reflecting midpoint alliance for these regressions. Scores at Time 1 and Time 4 were retained as measures of alliance early and late in treatment. For Aim 3, bivariate correlations were run to test the hypothesis that certain within-person variables at pretreatment (i.e., age, IQ, ASD severity, and co-occurring anxiety, depression, and ADHD symptoms) would be associated with alliance strength.

Results

Reliability

Approximately 20% (n = 30) of the total number of sessions coded were randomly selected to calculate interrater reliability using one-way random effects intraclass correlation coefficient (Shrout and Fleiss 1979). Interrater reliability was considered “excellent” (Cicchetti and Sparrow 1981) for the items (intraclass correlation coefficients ranged 0.81–0.97). Overall internal consistency of the VTAS-R-SF was also strong (α = 0.84). It was noted that correlations between item 5 (i.e., agreement between therapist and client on agenda) and other items were consistently weaker than correlations between the other 4 items. Given that the treatment program sessions had pre-defined treatment objectives and tasks that therapists must complete for each session, the amount that the client can contribute to creating an in-session agenda is limited. Thus, item 5, which measures how much the client independently brings up ideas for the agenda, does not seem to fit conceptually within the framework of this manualized treatment. Given the low intercorrelations with other items (range: r = 0.22–0.48) and limited ability to conceptually measure this aspect of alliance within the constraints of the program, item 5 was removed from the alliance variables for analyses. Removal of item 5 increased the overall internal consistency of the measure (α = 0.87).

Trajectory of Alliance Development Across Treatment

A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA showed that alliance significantly changed across treatment [F(3, 108) = 3.14, p = 0.028]. Pairwise comparisons indicated that alliance at Time 1 (M = 12.35, SE = 0.42) and Time 2 (M = 11.78, SE = 0.53) were significantly lower than alliance at Time 4 (M = 13.32, SE = 0.46). There were no significant differences between alliance at Time 3 (M = 12.54, SE = 0.47) and Time 4 or between Time 1, 2 and 3 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Total alliance strength across treatment

Although alliance is considered a unidimensional construct (Fjermestad et al. 2012), a series of one-way repeated-measures ANOVAs examining the trajectory of individual VTAS-R-SF items were conducted to gain a more detailed understanding of change in alliance across treatment. There was not a significant difference across treatment in the amount of support the client felt [item 1; F(3, 108) = 2.44, p = 0.068] or the client’s level of mistrust and defensiveness [item 3 reverse-coded; F(3, 108) = 1.52, p = 0.213]. However, there was a significant difference in the client’s level of participation in therapy tasks (item 2) across time [F(3, 108) = 4.16, p = 0.008]. Pairwise comparisons showed that clients’ participation at Time 1 (M = 2.73, SE = 0.13), Time 2 (M = 2.76, SE = 0.15), and Time 3 (marginally; M = 2.92, SE = 0.15) were significantly lower than their participation at Time 4 (M = 3.24, SE = 0.16). There was also a significant difference in the level of agreement on the client’s presenting problems (item 4) across treatment [F(3, 108) = 4.36, p = 0.006]. Level of agreement at Time 1 (M = 2.14, SE = 0.14) and Time 2 (M = 2.24, SE = 0.16) were both significantly lower than at Time 4 (M = 2.70, SE = 0.14).

Association Between Alliance Strength and Treatment Outcome

In the first regression model, posttreatment dysphoria was entered as the dependent variable and pretreatment dysphoria was entered as a predictor in step 1. Mean alliance was entered in step 2, resulting in a significant increase in R2, ΔF(1, 33) = 5.24, p = 0.029, ΔR2 = 0.11. The overall model accounted for 30% of the variance, F(2, 35) = 7.09, p = 0.003, R2 = 0.30. After controlling for baseline dysphoria, stronger mean alliance predicted decreased posttreatment dysphoria (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Association between mean alliance and posttreatment dysphoria

In the second regression model, posttreatment reactivity was entered as a dependent variable and pretreatment reactivity was entered as a predictor in step 1. Clients’ mean alliance was entered as a predictor in step 2, which did not result in a significant increase in R2, ΔF(1, 33) = 2.40, p = 0.131, ΔR2 = 0.05. The overall model remained significant, F(2, 35) = 8.72, p = 0.001, R2 = 0.35. After controlling for pretreatment reactivity, mean alliance strength was not a unique predictor of posttreatment reactivity. See Table 3 for full information on models 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Regression analyses examining mean alliance strength and treatment outcomes

| Step 1 |

Step 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | T | b | SE | β | t | |

| DV: post dysphoria | R2 = .19 | R2 = .26, ΔR2 = .11 | ||||||

| Pre dysphoria | .44 | .16 | .44 | 2.82 | .38 | .15 | .38 | 2.56* |

| Alliance | – | – | – | – | −1.25 | .55 | −.34 | −2.29* |

| DV: post reactivity | R2 = .30 | R2 = .35, ΔR2 = .05 | ||||||

| Pre reactivity | .52 | .14 | .55 | 3.80** | .53 | .14 | .55 | 3.91* |

| Alliance | – | – | – | – | −.74 | .48 | −.22 | −1.55 |

p < .05

p < .001

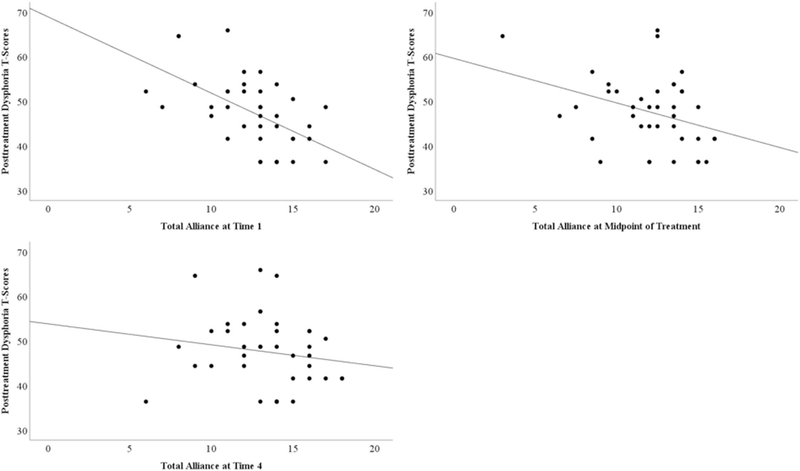

In the third regression model predicting posttreatment dysphoria T-scores, pretreatment dysphoria T-scores were entered in step 1 and alliance at Time 1, midpoint, and Time 4 were entered in step 2. This resulted in a significant increase in R2, ΔF(3, 31) = 3.06, p = 0.043, ΔR2 = 0.19. The full model accounted for 37% of the variance, F(4, 35) = 4.64, p = 0.005, R2 = 0.37. After controlling for pretreatment dysphoria, alliance at Time 1 uniquely predicted posttreatment dysphoria; specifically, stronger alliance at Time 1 was associated with less dysphoria at posttreatment. See Fig. 3 for an illustration of individual predictors.

Fig. 3.

Association between alliance across treatment and posttreatment dysphoria

In the fourth regression model predicting posttreatment reactivity T-scores, pretreatment reactivity T-scores were entered in step 1 and alliance at Time 1, midpoint, and Time 4 were entered as individual predictors in step 2. This did not result in a significant increase in R2, ΔF(3, 31) = 1.41, p = 0.259, ΔR2 = 0.08. The full model remained significant, F(4, 35) = 4.79, p = 0.004, R2 = 0.38, although there were no other significant predictors of posttreatment reactivity after controlling for pretreatment reactivity. See Table 4 for full information on models 3 and 4.

Table 4.

Regression analyses examining alliance across treatment and treatment outcomes

| Step 1 |

Step 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | t | b | SE | β | t | |

| DV: post dysphoria | R2 = .19 | R2 = .37, ΔR2 = .19 | ||||||

| Pre dysphoria | .44 | .16 | .44 | 2.82* | .33 | .15 | .33 | 2.27* |

| Time 1 alliance | – | – | – | – | −1.23 | .53 | −.40 | −2.33* |

| Midpoint alliance | – | – | – | – | −.39 | .50 | −.13 | −.79 |

| Time 4 alliance | – | – | – | – | .23 | .45 | .08 | .51 |

| DV: post reactivity | R2 = .30 | R2 = .38, ΔR2 = .08 | ||||||

| Pre reactivity | .52 | .14 | .55 | 3.80* | .49 | .14 | .52 | 3.50* |

| Time 1 alliance | – | – | – | – | −.79 | .48 | −.28 | −1.64 |

| Midpoint alliance | – | – | – | – | .05 | .45 | .02 | .11 |

| Time 4 alliance | – | – | – | – | −.12 | .42 | −.05 | −.29 |

p < .05

Predictors of Alliance Strength

There was a moderate negative correlation between mean alliance strength and depression symptoms, r(36) = −0.34, p = 0.039. Although not statistically significant at the p = 0.05 level, the association between mean alliance strength and ASD symptoms was of a similar magnitude and approaching statistical significance, r(37) = −0.31, p = 0.055. Clients with more co-occurring depression symptoms or higher ASD severity were more likely to have weaker overall mean alliance with their therapists. There was not a statistically significant relationship between alliance strength and any other variables (see Table 2).

Exploratory analyses were conducted to see if any of these within-person variables were associated with alliance strength formed early in treatment (Time 1) given that early alliance is associated with positive ER treatment outcomes. Alliance at Time 1 was not significantly related to any within-person characteristics, although there was a moderate negative association between alliance at Time 1 and depression symptoms that was approaching statistical significance, r(36) = −0.30, p = 0.064.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the role of therapeutic alliance formation in treatment of adolescents and young adults with ASD using an observational measure of alliance. Previous research has largely relied on self-report ratings, sometimes retrospectively (Kerns et al. 2018;Klebanoff et al. 2019). This is a reasonable approach that provides valuable information on client and therapist perspectives of treatment; however, given concerns about self-report and the level of insight for individuals with ASD (Pearl et al. 2017; White et al. 2012), observational coding offers an unbiased and direct evidence-driven approach to measuring alliance, as well as quantification of alliance at multiple points during treatment.

In the current study, interrater reliability and internal consistency of the VTAS-R-SF were high, indicating that the alliance construct can be reliably coded by trained raters. However, the 5-item measure poses an interesting question about the applicability of the VTAS-R-SF for studies utilizing manualized treatments. Specifically, the theoretical basis of item 5 (i.e., client and therapist’s agreement on the session tasks) did not seem to fit with a manualized treatment given that session tasks were outlined at the outset of treatment. The number of manualized treatments for treating co-occurring problems in ASD is growing (Kerns et al. 2016; Storch et al. 2015; White et al. 2013); thus, the reliability of the VTAS-R-SF to characterize alliance in a manualized treatment seems promising for therapy process research in ASD.

The findings also suggest that alliance fluctuates throughout treatment for clients with ASD. The dip in alliance at Time 2 could reflect a natural adjustment to therapy; it may be that when clients with ASD enter therapy, they are generally very compliant towards their therapist, and as they get more accustomed to this new situation, clients are less willing to follow along with their therapist’s expectations. In fact, research suggests that alliance fluctuates throughout treatment (Chu et al. 2014). Importantly, some of these clients were brought to therapy by their parents, rather than seeking help themselves, and may be less willing to comply once they have attended several sessions. This dip may also be attributable to elements specific to sessions captured in Time 2. This portion of the treatment, in this program, is spent engaging in emotionally arousing situations to practice skills or mindfulness exercises to build clients’ emotional self-awareness; it could be that clients may have felt less support given that their therapists are the ones encouraging them to engage in distressing situations. Similar decreases in clients’ level of support and level of trust/lack of defensiveness at Time 2 seem to support this idea. However, previous literature examining alliance during exposure tasks, which are similar to the practices in EASE, suggest that alliance is not ruptured during exposures (Chu et al. 2014; Kendall et al. 2009). Additional research measuring the trajectory of alliance formation in different treatments for ASD is needed to better understand whether these results reflect something specific to the treatment or therapeutic process generally.

The trajectories for the level of the client’s participation (item 2) and agreement on the client’s presenting problem (item 4) present a promising picture. Over the course of treatment, there is a significant increase in both of these facets of alliance. This suggests that therapists are able to establish a good working relationship with their clients with ASD in which clients feel buy-in to what they are working on in therapy and have built awareness of their underlying difficulties with ER, which are vital to make improvements.

The strength of overall alliance appears important to treatment outcomes for individuals with ASD, which mirrors non-ASD literature (Flückiger et al. 2018; McLeod and Weisz 2005; Shirk and Karver 2003). Specifically, strong alliance is associated with improvement in dysphoria. The EDI’s dysphoria scale is designed to capture clients’ diminished positive affect (e.g., happiness or joy); as such, these results suggest that solid relationship building in therapy leads to general improvement in one’s ability to upregulate positive affect, as well as reduction of one’s amotivation or sadness about life. An instrumental part of therapy is developing a warm and collaborative bond with one’s therapist and, if done successfully, it likely that this relationship could be a source of comfort and support for clients. Furthermore, individuals with ASD characteristically struggle with developing interpersonal relationships and many experience increased loneliness and depression because of this difficulty (Cooper et al. 2017; Hedley et al. 2018). Thus, having a good bond with one’s therapist may offer unique benefit for clients with ASD that decreases dysphoria. Alliance at Time 1 was also a unique predictor of dysphoria outcomes. This finding suggests that alliance can be developed quickly and have an important impact on treatment outcomes. Spending additional time to build strong alliance in the initial sessions of therapy could be beneficial for clients with ASD, particularly for those who are slow to warm or less motivated. Given this relationship, it is also important to consider how to build alliance in other treatment modalities, such as group-based interventions, that may not find as much change in dysphoria (Shaffer et al. 2020).

In contrast, alliance strength, both overall and at separate timepoints, was not associated with improvement in clients’ levels of reactivity. This finding is inconsistent with previous, non-ASD literature suggesting that strong alliance is particularly critical for outcomes for clients with externalizing disorders as presenting problems (i.e., conduct disorder, ADHD, etc.; Karver et al. 2018;Shirk and Karver 2003). Reactivity has been linked to many externalizing disorders and proposed as a possible transdiagnostic mechanism (Brotman et al. 2017;Graziano and Garcia 2016). Although reactivity is associated with externalizing disorders, it may not be influenced by a strong alliance in the same way that alliance influences change in externalizing symptoms.

Given the relationship between alliance and treatment outcomes, this study began to identify specific client characteristics that are associated with forming strong alliance. Clients’ ASD symptom severity and co-occurring depression symptoms were the only two variables that were associated with alliance formation, both overall alliance and alliance early in treatment (for depression symptoms, only). A core symptom of ASD is difficulty in developing relationships, so it may be that clients who are more severely affected lack the motivation or skill to appropriately and effectively develop a strong alliance. Additionally, certain depression symptoms (e.g., social withdrawal, hopelessness, lethargy) may inhibit easy formation of strong alliances in therapy. The lack of association between age and alliance, particularly at Time 1, is surprising since younger clients are often brought to therapy by their parents, rather than choosing to pursue therapy themselves. If the VTAS-R-SF measure accurately captured alliance for clients in the current study, regardless of their age, then the finding may be a promising sign that therapists are able to establish alliance with both their adolescent and adult clients with ASD. Additional research on within-person client characteristics is necessary to continue identifying which clients with ASD may be at risk of forming weak alliances. Given limited evidence suggesting that therapists’ personality traits or abilities can also influence alliance formation for non-ASD clients (Nienhuis et al. 2018), future research should determine if therapist characteristics are important for developing strong alliances with clients with ASD.

Limitations

The limitations of the current study are important to note. Although the VTAS-R-SF has been used in a variety of clinical populations (Feder and Diamond 2016; Mcleod et al. 2017; Shelef and Diamond 2008), it has not been validated using an ASD sample. The VTAS-R-SF may not be sensitive to how alliance might manifest in therapy with clients who have ASD. However, no tools exist yet that have been modified to measure alliance for individuals with ASD and a primary aim of the study was to begin to characterize alliance in ASD; thus, the findings may help to create tools designed for this population. Another limitation is that coders were not completely blind to the session they were coding, although precautions were taken to limit the possibility of coder bias. Although the study utilizes multi-method data (e.g., observational and parent-report data), the lack of self-report measures is a limitation and could provide unique information about how alliance is related to clients’ perceptions of their ER difficulties. Likewise, the sample is small and relatively homogenous, which limits generalizability of findings, although the sample size is similar to other studies analyzing alliance in ASD (Kerns et al. 2018; Murphy et al. 2017). Lastly, data were collected from a clinical trial with specific inclusion/exclusion criteria, so it is possible that findings may differ in a less structured community-based setting or when looking at a different outcome.

Implications and Future Directions

The current study utilizes methodology that is novel for ASD research on alliance, specifically the unbiased, observational measure and capacity to characterize alliance formation at multiple points in treatment. We have surmised that alliance, an integral facet of the therapy process, does indeed predict treatment outcomes for clients with ASD. The findings also demonstrate that alliance fluctuates during crucial times in treatment, highlighting a need for increased alliance formation during these stages. Furthermore, specific client characteristics such as ASD symptom severity and co-occurring depressive symptoms impact alliance formation. Future research should explore the degree to which treatment approach moderates the importance of alliance to outcome. Overall, given emerging evidence that alliance can change and is associated with treatment outcomes for clients with ASD, purposefully targeting alliance formation early in treatment, particularly for clients who struggle to form strong alliances, may enhance treatment development and maximize successful outcomes for clients with ASD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Grant R01HD079512 (PI: Mazefsky), Edith L. Trees Charitable Trust, and Department of Defense, Grant W81XWH-18-1-0284 (PI: Mazefsky). We acknowledge these funding sources for their support and the many colleagues who assisted us with various aspects of the present research. We also acknowledge that this manuscript is prepared from a master’s thesis by the first author.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Statement Involving Human and Animal Rights All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board for human subject research.

Informed Consent Participants provided informed consent.

References

- Accurso EC, & Garland AF (2015). Child, caregiver, and therapist perspectives on therapeutic alliance in usual care child psychotherapy. Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 347–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, & Rescorla L (2003). Manual for the ASEBA adult forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Albaum C, Tablon P, Roudbarani F, & Weiss JA (2020). Predictors and outcomes associated with therapeutic alliance in cognitive behaviour therapy for children with autism. Autism, 24(1), 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz S, Hill E, & L., (2005). The validity of using self-reports to assess emotion regulation abilities in adults with autism spectrum disorder. European Psychiatry, 20(3), 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordin ES (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 16(3), 252–260. [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Kircanski K, Stringaris A, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2017). Irritability in Youths: A translational model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(6), 520–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham Riosa P, Khan M, & Weiss JA (2019). Measuring therapeutic alliance in children with autism during cognitive behavior therapy. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 26(6), 761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachia RL, Anderson A, & Moore DW (2016). Mindfulness in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and narrative analysis. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 3(2), 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, Skriner LC, & Zandberg LJ (2014). Trajectory and predictors of alliance in cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43(5), 721–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Sparrow S (1981). Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 86(2), 127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner CM, & White SW (2018). Brief report: Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of individual mindfulness therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner CM, White SW, Beck KB, Golt J, Smith IC, & Mazefsky CA (2019). Improving emotion regulation ability in autism: The Emotional Awareness and Skills Enhancement (EASE) program. Autism, 23(5), 1273–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner CM, White SW, Scahill L, & Mazefsky CA (2020). The role of emotion regulation and core autism symptoms in the experience of anxiety in autism. Autism, 24(4), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino J, & Gruber C (2012). Social responsiveness scale: SRS-2. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper K, Smith LGE, & Russell A (2017). Social identity, self-esteem, and mental health in autism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(7), 844–854. [Google Scholar]

- Feder MM, & Diamond GM (2016). Parent-therapist alliance and parent attachment-promoting behaviour in attachment-based family therapy for suicidal and depressed adolescents. Journal of Family Therapy, 38(1), 82–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fjermestad KW, McLeod BD, Heiervang ER, Havik OE, Öst LG, & Haugland BSM (2012). Factor structure and validity of the therapy process observational coding system for child psychotherapy-alliance scale. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41(2), 246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger C, Del AC, Wampold BE, & Horvath AO (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, & Garcia A (2016). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and children’s emotion dysregulation: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 46, 106–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, & Cavanagh K (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley D, Uljarević M, Wilmot M, Richdale A, & Dissanayake C (2018). Understanding depression and thoughts of self-harm in autism: A potential mechanism involving loneliness. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Holzel B, Carmody J, Vangel M, Congleton C, Yerramsetti S, Gard T, et al. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research, 191(1), 36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows: Version 24.0. New York: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Karver MS, De Nadai AS, Monahan M, & Shirk SR (2018). Meta-analysis of the prospective relation between alliance and outcome in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Durbin KA (2012). Predictors of child-therapist alliance in cognitive—behavioral treatment of children referred for oppositional and antisocial behavior. Psychotherapy, 49(2), 202–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Comer JS, Marker CD, Creed TA, Puliafico AC, Hughes AA, et al. (2009). In-session exposure tasks and therapeutic alliance across the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Collier A, Lewin AB, & Storch EA (2018). Therapeutic alliance in youth with autism spectrum disorder receiving cognitive—behavioral treatment for anxiety. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 22(5), 636–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Wood JJ, Kendall PC, Renno P, Crawford EA, Mercado RJ, et al. (2016). The treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorder (TAASD) study: Rationale, design and methods. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(6), 1889–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiep M, Spek AA, & Hoeben L (2015). Mindfulness-based therapy in adults with an autism spectrum disorder: Do treatment effects last? Mindfulness, 6(3), 637–644. [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff SM, Rosenau KA, & Wood JJ (2019). The therapeutic alliance in cognitive—behavioral therapy for school-aged children with autism and clinical anxiety. Autism, 23(8), 2031–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore P, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop SL, et al. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J, Washington A, Patrick M, DiRienzo M, et al. (2020). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 69(4), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Borue X, Day TN, & Minshew NJ (2014). Emotion regulation patterns in adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: Comparison to typically developing adolescents and association with psychiatric symptoms. Autism Research, 7(3), 344–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Day TN, Siegel M, White SW, Yu L, & Pilkonis PA (2018). Development of the emotion dysregulation inventory: A PROMIS®ing method for creating sensitive and unbiased questionnaires for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(11), 3736–3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Kao J, & Oswald DP (2011). Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 164–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, & White SW (2014). Emotion regulation. Concepts and practice in autism spectrum disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(1), 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, White SW, Beck KB, & Conner CM (2020). The Emotion Awareness and Skills Enhancement (EASE) program. In Volkmar FR (Ed.), Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders (Vol. 2). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mcleod BD, Southam-Gerow MA, & Kendall PC (2017). Observer, youth, and therapist perspectives on the alliance in cognitive behavioral treatment for youth anxiety. Psychological Assessment, 29(12), 1550–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, & Weisz JR (2005). The therapy process observational coding system-alliance scale: Measure characteristics and prediction of outcome in usual clinical practice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(2), 323–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, Chowdhury U, White SW, Reynolds L, Donald L, Gahan H, et al. (2017). Cognitive behaviour therapy versus a counselling intervention for anxiety in young people with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3446–3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nienhuis JB, Owen J, Valentine JC, Winkeljohn Black S, Halford TC, Parazak SE, et al. (2018). Therapeutic alliance, empathy, and genuineness in individual adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy Research, 28(4), 593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Day TN, Jones N, & Mazefsky CA (2017). Association between anger rumination and autism symptom severity, depression symptoms, aggression, and general dysregulation in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(2), 181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl AM, Edwards EM, & Murray MJ (2017). Comparison of self-and other-report of symptoms of autism and comorbid psychopathology in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Contemporary Behavioral Health Care, 2(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pouw LBC, Rieffe C, Stockmann L, & Gadow KD (2013). The link between emotion regulation, social functioning, and depression in boys with ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(4), 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Samson AC, Hardan AY, Podell RW, Phillips JM, & Gross JJ (2015). Emotion regulation in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 8(1), 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson AC, Huber O, & Gross JJ (2012). Emotion regulation in Asperger’s syndrome and high-functioning autism. Emotion, 12(4), 659–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer JÖ, Naumann E, Holmes EA, Tuschen-Caffier B, & Samson AC (2017). Emotion regulation strategies in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(2), 261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer RC, Schmitt LM, Adams R, Reisinger D, Ruberg J, Randall S, et al. (2020). Initial trial outcomes of Regulating Together: Emotion regulation treatment for children and teens with ASD in an intensive, group, parent-assisted program (Panel session). In INSAR Annual Meeting.

- Shelef K, & Diamond GM (2008). Short form of the revised Vanderbilt Therapeutic Alliance Scale: Development, reliability, and validity. Psychotherapy Research, 18(4), 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, & Karver M (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 452–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, & Karver MS (2011). Alliance in child and adolescent therapy. In Norcross JC (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, & Saiz C (1992). Clinical, empirical, and developmental perspectives on the therapeutic relationship in child psychotherapy. Development and Psychopathology, 4(4), 713–728. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Fleiss JL (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. 1. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Lewin AB, Collier AB, Arnold E, De Nadai AS, Dane BF, et al. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive—behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety. Depression and Anxiety, 32(3), 174–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson K, Burnham Riosa P, & Weiss JA (2015). Brief report of preliminary outcomes of an emotion regulation intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(11), 3487–3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2011). WASI-II: Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JA (2014). Transdiagnostic case conceptualization of emotional problems in youth with ASD: An emotion regulation approach. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(4), 331–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JA, Thomson K, Burnham Riosa P, Albaum C, Chan V, Maughan A, et al. (2018). A randomized waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy to improve emotion regulation in children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 59(11), 1180–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Ollendick T, Albano AM, Oswald D, Johnson C, Southam-Gerow MA, et al. (2013). Randomized controlled trial: Multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(2), 382–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Schry AR, & Maddox BB (2012). Brief report: The assessment of anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 1138–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzella KPM, Muller RT, & Cribbie RA (2015). The relationships between therapeutic alliance and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Child Abuse and Neglect, 50, 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]