Abstract

In the kynurenine pathway for tryptophan degradation, an unstable metabolic intermediate, α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde (ACMS), can nonenzymatically cyclize to form quinolinic acid, the precursor for de novo biosynthesis of NAD+. In a competing reaction, ACMS is decarboxylated by ACMS decarboxylase (ACMSD) for further metabolism and energy production. Therefore, the inhibition of ACMSD increases NAD+ levels. In this study, an FDA-approved drug, diflunisal, was found to competitively inhibit ACMSD. The complex structure of ACMSD with diflunisal revealed a previously unknown ligand-binding mode and was consistent with results of inhibition assays, as well as a structure-activity relationship (SAR) study. Moreover, two synthesized diflunisal derivatives showed IC50 values one order of magnitude better than diflunisal at 1.32 ± 0.07 μM (22) and 3.10 ± 0.11 μM (20), respectively. The results suggest that diflunisal derivatives have the potential to modulate NAD+ levels. The ligand-binding mode revealed here provides a new direction for developing inhibitors of ACMSD.

Keywords: FDA-approved drugs, NAD+, neuropsychiatric disorders, structure-activity relationship (SAR), decarboxylase

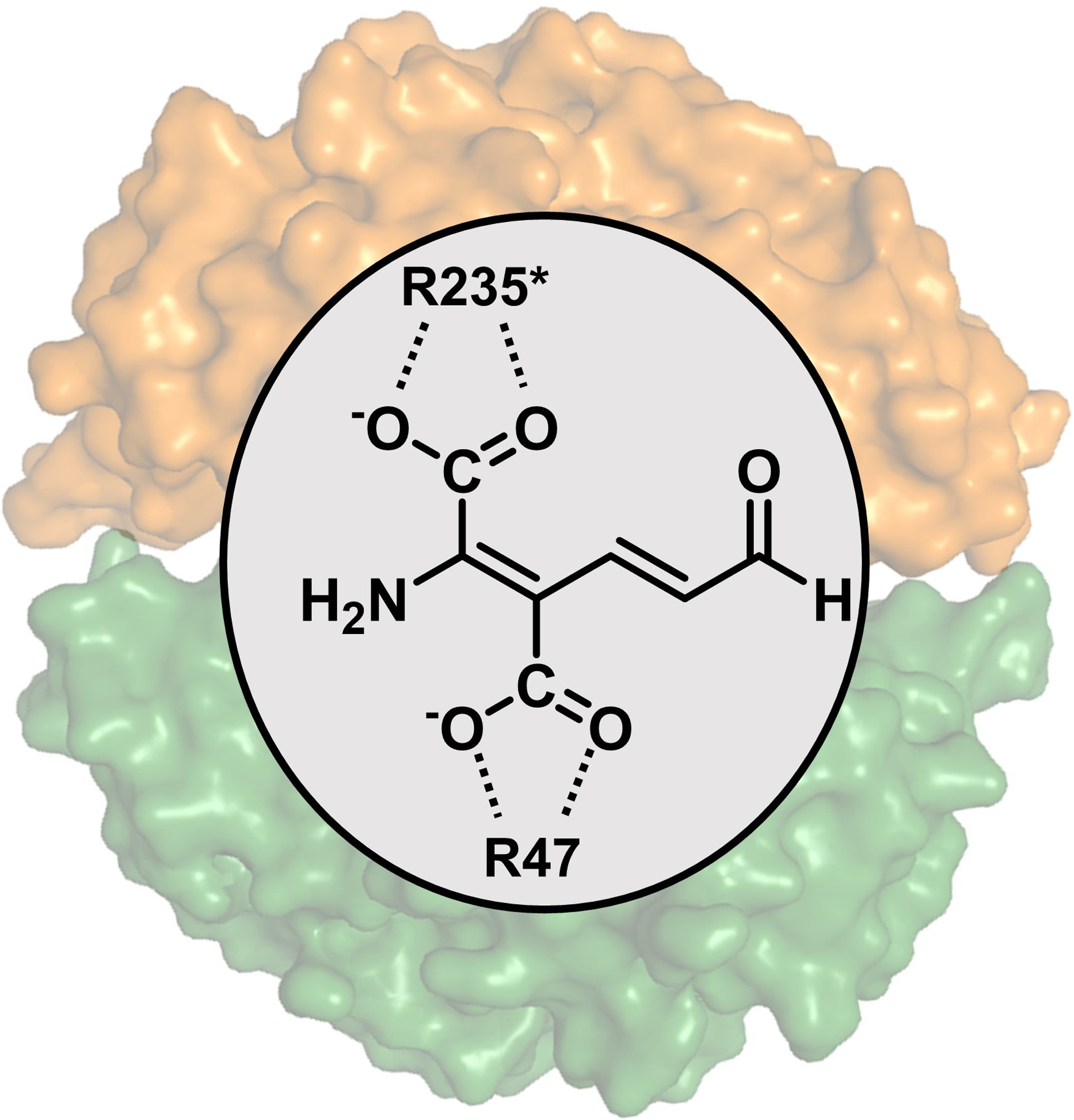

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, NAD(P)+, is an essential redox cofactor across all kingdoms of life. The de novo synthesis of NAD+ in mammals and some bacteria starts from the tryptophan-kynurenine degrading pathway (Figure 1). A transient metabolite of the pathway, α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde (ACMS), in its enol tautomer form, is a metabolic intermediate at the crossroad between NAD+ biosynthesis and energy production.1 ACMS is unstable and can nonenzymatically cyclize to form quinolinic acid (QUIN), a precursor for NAD+ synthesis. In a competing pathway, the β-carboxylic group of ACMS can be enzymatically removed by a Zn-dependent decarboxylase (ACMSD) to form α-aminomuconate semialdehyde (2-AMS) for further enzyme-mediated catabolism. Therefore, the QUIN levels are directly regulated by ACMSD and could become elevated by inhibiting ACMSD. The regulation of NAD+ levels through modulating ACMSD activity has been experimentally demonstrated in mice, as high-expression of ACMSD led to a niacin dependent phenotype.2, 3 QUIN is also an endogenous agonist of NMDA receptors.4 Misregulated QUIN production is linked to a wide range of neuropsychiatric disorders.5–8 In bacteria, such as Pseudomonas fluorescence, biodegradation of 2-nitrobenzoic acid can enter the kynurenine pathway, though this substrate avoids the first two steps.9

Figure 1.

Inhibition of ACMSD increases NAD+ biosynthesis.

ACMSD occupies a central position in both metabolic pathways. The discovery of the bacterial protein has facilitated biochemical and structural studies. ACMSD belongs to the amidohydrolase superfamily,10 and it is a prototypic member for a large subgroup of decarboxylases and hydratases.10, 11 This enzyme performs a metal-mediated, O2-independent, nonoxidative decarboxylation reaction,12 which proceeds through a metal-bound hydroxide.13 The crystal structures of ACMSD from both human and P. fluorescence have been previously determined.11, 14 ACMSD is catalytically inactive in the monomer form and active in the homodimer form, because the neighboring subunit contributes one of the two substrate-binding arginine residues.15 The enzyme shows a protein concentration-dependent activity, as its quaternary structure is in a dynamic equilibrium among monomer, dimer, and higher-order oligomeric states.16 Pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic (PDC) acid is a biochemically established inhibitor (Scheme 1A).14 In the crystal structure of human ACMSD in complex with PDC,14 or another inhibitor 1,3-dihydroxy-acetonephosphate (DHAP),17 the inhibitors are located near the zinc center and are recognized by a substrate-binding residue, Arg47. A phthalate ester, mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate, also reportedly reversibly inhibited ACMSD activity and increased QUIN levels as detected in the urinary excretion of rats.18

Scheme 1.

A) The chemical structures of reported inhibitors of ACMSD. B) Virtual screening delivered computational hits that bound the catalytically active Zn center using a carboxylate group (PDB entry: 4IH3). C) The computationally predicted docking pose for diflunisal predicts that the salicylate head interacts near catalytically active the Zn2+, while the difluorinated aryl ring projects through a hydrophobic tunnel.

In 2018, an effective, nanomolar inhibitor of ACMSD, TES-1025, was developed based on published structural information in complex with PDC and DHAP.17, 19 In cellular systems, inhibiting ACMSD activity increased NAD+ concentration and enhanced QUIN formation. Using in vivo knockout systems and pharmacological intervention with TES-1025, further comprehensive investigations demonstrated that inhibition of ACMSD activity similarly increased NAD+ concentration and sirtuin activity and improved mitochondrial function in Caenorhabditis elegans, mouse, and human tissues, such as liver and kidney in which ACMSD highly expressed.3 How TES-1025 binds ACMSD and its mechanism of inhibition have not been determined.

Compared with developing an entirely new drug, expanding new uses of FDA-approved drugs can be much less costly and can deepen the understanding of the drugs in the human body. Here, we screened FDA-approved drugs to develop inhibitors of ACMSD. Diflunisal was identified to inhibit ACMSD, and the mechanism of inhibition was characterized. Diflunisal derivatives were synthesized to elucidate the functional groups and improve overall inhibition. Co-crystal structures of ACMSD with the new inhibitors revealed a previously unknown inhibitor-binding mode in the active site of ACMSD, which involved residues distant from the zinc center. These findings provide a new direction for developing ACMSD inhibitors.

Results

1. Molecular modeling of the FDA-approved drugs in the active site of ACMSD

A library of roughly 5000 FDA-approved drugs was screened for binding at the active site of human ACMSD14 by rigid-receptor docking using Glide20–23 at successively increasing precision levels. The highest scoring 62 unique compounds were chosen for refinement using Prime MM-GBSA,23–25 and the refined ligand-bound structures, along with the chemical structures, fell into several clusters of compounds that potentially bind human ACMSD: bisphosphonates, citrates, ibuprofen-derived nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS, cyclooxygenase inhibitors),26, 27 salicylate-derived NSAIDS, and other miscellaneous compounds (Table S1). The docking models suggested that most of these compounds might bind ACMSD in the active site through a carboxylate that interacts with the zinc ion (Scheme 1B). A linear lipophilic stem that sticks through the active pocket might also help engage the enzyme. From each cluster, structurally diverse compounds were acquired. Depending on the group, 1 to 6 compounds were selected as representative of possible structural diversity, and a total of 14 representative compounds was chosen from each cluster to test the inhibition of ACMSD activity (Scheme S1, Table 1).

Table 1.

Initial assessment of FDA-approved drugs recommended by the computational docking study

| Compounds (1 mM) | PA (%) | QUIN (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control (ACMSD) | 83.6 ± 3.1 | 16.4 ± 2.9 |

| Risedronate | 82.7 ± 7.1 | 17.4 ± 5.2 |

| Alendronic Acid | 99.6 ± 1.9 | 0.43 ± 0.24 |

| Ibandronate | 98.7 ± 2.2 | 1.29 ± 0.18 |

| Citric Acid | 78.6 ± 7.8 | 21.4 ± 2.9 |

| Ibuprofen | 75.4 ± 1.4 | 24.6 ± 1.7 |

| Fenoprofen | 75.9 ± 3.0 | 24.1 ± 4.5 |

| Ketoprofen | 76.0 ± 1.2 | 24.0 ± 1.7 |

| Fenbufen | 78.2 ± 2.4 | 21.8 ± 1.3 |

| Mitiglinide | 98.7 ± 6.4 | 1.26 ± 0.55 |

| Naproxen | 88.9 ± 3.3 | 11.1 ± 1.7 |

| Tolmetin | 85.1 ± 2.9 | 14.9 ± 1.5 |

| Aminohippuric acid | 95.0 ± 3.4 | 5.03 ± 0.77 |

| Pregabalin | 97.0 ± 3.5 | 2.98 ± 0.69 |

| Diflunisal (1) | 6.9 ± 0.3 | 93.1 ± 3.2 |

2. Discovery of diflunisal inhibition over human ACMSD

To rapidly screen compounds prior to conducting more comprehensive inhibition studies, we developed an enzymatic method to assess the inhibition of human ACMSD by quantitation of the relevant kynurenine products by HPLC. Both the substrate (ACMS, t1/2 = 46 min at pH 7.0 and 20 °C) and the immediate product (2-AMS, t1/2 = 35 s at pH 7.0 and 20 °C) of the ACMSD reaction are unstable,28 and spontaneously decay to QUIN and picolinic acid (PA), respectively. Thus, in this enzymatic assay, the production of PA serves as a direct reporter of ACMSD activity, as the decarboxylation product 2-AMS undergoes cyclization to form PA (Table 1). Alternatively, inhibition of ACMSD would facilitate formation of QUIN. In practice, the reaction mixtures contained 1 mM of test compound and were run overnight to ensure complete formation of the decay products. Then, QUIN and PA were separated and quantitated from the reaction mixtures by HPLC.

As shown in Table 1, compared with the control sample (no inhibitor), 13 of the 14 candidates showed no significant differences in the distribution of PA vs. QUIN, indicating they had no apparent inhibition of ACMSD activity, and thus, these computational hits were not pursued further. The presence of the pain reliever, diflunisal (1), however, generated significant quantities of ACMS-derived QUIN (93%), and only a small amount of the decarboxylation product-derived product PA (7%), indicating that ACMSD was nearly completely inhibited by diflunisal under the assay conditions. At this point, reinspection of the docked pose predicted that the phenol presented toward the catalytic Zn2+, while the carboxylate engaged the N–H of Trp191. Further, the difluorinated ring was predicted to protrude through a narrow hydrophobic tunnel comprised of Phe46, Val78, Met178, Met180, and Trp191 (Scheme 1C).

3. Determination of structure-activity relationships for inhibition of ACMSD by diflunisal derivatives

To further probe the structural determinants required for inhibition of ACMSD, a structure-activity relationship (SAR) study was pursued using a molecular simplification approach. Diflunisal contains two phenyl rings in which one ring (A) has a hydroxyl group and a carboxylate substituent, and the other ring (B) has two fluoro substituents (Table 2). Like the previously reported inhibitors,14, 15, 17, 19 diflunisal shares the common feature of a carboxylate group. The SAR assay for diflunisal inhibiting ACMSD activity was performed by systematically altering each of the substituents of diflunisal and measuring the inhibition of each derivative (Table 2). For ring A, the carboxylate and hydroxyl groups were either removed separately (2 & 3) or substituted with CH2OH (4), COOCH3 (5), and CONH2 (6). For ring B, the fluorine atoms were substituted with hydrogen (7, 8, 10) or shifted to the meta position (9). Additionally, analogs 11–13 explored the significance of the B ring.

Table 2.

Metabolic flux ratio of PA and QUIN

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Ring A | Ring B | PA (%) | QUIN (%) |

| Control (no inhibitor) | 83.6 ± 3.1 | 16.4 ± 2.9 | ||

| Diflunisal (1) | 1 = COOH; 2 = OH | 2’ = F; 4’ = F | 6.9 ± 0.3 | 93.1 ± 3.2 |

| 2 | 1 = COOH; 2 = H | 2’ = F; 4’ = F | 77.0 ± 1.3 | 23.0 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 1 = H; 2 = OH | 2’ = F; 4’ = F | 73.3 ± 0.6 | 26.7 ± 2.0 |

| 4 | 1 = CH2OH; 2 = OH | 2’ = F; 4’ = F | 82.3 ± 0.2 | 17.7 ± 0.3 |

| 5 | 1 = COOCH3; 2 = OH | 2’ = F; 4’ = F | 83.4 ± 0.2 | 16.6 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 1 = CONH2; 2 = OH | 2’ = F; 4’ = F | 82.1 ± 0.6 | 17.9 ± 0.6 |

| 7 | 1 = COOH; 2 = OH | 2’ = H; 4’ = F | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 94.0 ± 5.5 |

| 8 | 1 = COOH; 2 = OH | 2’ = F; 4’ = H | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 94.7 ± 0.6 |

| 9 | 1 = COOH; 2 = OH | 2’ = H; 3’ = F; 4’ = H | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 97.1 ± 3.1 |

| 10 | 1 = COOH; 2 = OH | 2’ = H; 4’ = H | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 94.9 ± 0.4 |

| 11 | 1 = COOH; 2 = OH | 3-thiophene | 0.82 ± 0.38 | 99.2 ± 3.1 |

| 12 | 1 = COOH; 2 = OH | None | 100 ± 2.1 | ND |

| 13 | 1 = COOH; 2 = OH | 4 = Ph | 27.2 ± 2.3 | 73 ± 11 |

The preparation of compounds 4–6, bearing distinct functional groups on the A ring, were accessed from diflunisal, itself, via reduction, esterification, and amidation reactions (Scheme 2A). The synthetic route for accessing diflunisal derivatives (7–11) generally involved Suzuki coupling of 5-bromo salicylic acid (14) or the corresponding ester (15) with properly substituted arylboronic acids under aqueous conditions (Scheme 2B).29

Scheme 2.

Preparation of compounds 4–11.

As shown in Table 2, the reaction mixtures containing 2–6 produced similar amounts of PA compared with the control, suggesting no inhibition of ACMSD activity. As such, both the carboxylate and hydroxyl groups are essential for inhibiting ACMSD. Diflunisal derivatives with a modified B ring (7–11) inhibited ACMSD similarly as diflunisal. Therefore, the positioning of the fluoro groups on the B ring did not significantly contribute to the inhibition of ACMSD. Because the A ring of diflunisal bears the salicylic acid (2-hydroxybenozic acid) moiety, the active component of aspirin, salicylic acid (12) itself was included in this set of experiments as a simplified analog. Interestingly, even with both the carboxylate and hydroxyl groups of the A ring, no inhibition was observed (Table 2), though a more sensitive assay did detect weak inhibition with an IC50 above 500 μM (data not shown). These findings suggest that the B ring moiety was also essential for effectively inhibiting ACMSD activity. Derivative 13, in which the B ring was switched from meta- to para- position demonstrated poor inhibition, with less than one-third of PA in the mixture relative to diflunisal.

It has been previously shown that the active site structures of human ACMSD and Pseudomonas fluorescens ACMSD (pfACMSD) are superimposable and nearly indistinguishable.14 The two proteins also share 56% sequence identity. However, the bacterial enzyme is more robust and produces better quality crystals. Thus, pfACMSD was used to pursue inhibitor-bound complex structures that would facilitate studying the inhibitory mechanism. Crystals of ACMSD were soaked with mother liquor containing diflunisal to obtain an inhibitor-bound complex structure. The ACMSD-diflunisal complex structure (Figure 2A) was obtained and refined to the resolution of 2.17 Å (Table 3). The overall structure of the ACMSD-diflunisal complex was similar to the ligand-free ACMSD structure,10 as indicated by a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) value of 0.272 Å for all Cα carbons.

Figure 2.

The crystal structure of pfACMSD in complex with diflunisal (PDB entry: 7K12). A) The enlarged figure shows the residues (green sticks) that interact with diflunisal (yellow sticks). The 2Fo - Fc (gray) and omit Fo - Fc (marine) maps for diflunisal (1) are contoured at 1 and 2.5 σ, respectively. The aligned residues from hACMSD are labeled in blue for comparison. B) Superimposed the ACMSD-diflunisal complex structure (green) with the ligand-free ACMSD structure (grey, PDB entry: 2HBV). The substrate is set with 50% transparency for better presentation. C) Two loop regions move toward diflunisal (1). D) Competitive inhibition of human ACMSD measured at 1.3, 5, 10, 16, and 22.5 μM of diflunisal (1) (black, red, blue, pink, and green traces, respectively).

Table 3.

Crystallization data collection and refinement statistics.

| ACMSD in complex with diflunisal | ACMSD in complex with 11 | |

|---|---|---|

| PDB code | 7K12 | 7K13 |

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P6122 | C2221 |

| Cell dimensions a, b, c (Å) |

93.6, 93.6, 445.7 | 105.0, 150.6, 153.7 |

| σ, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution | 50 – 2.17 (2.21 – 2.17)a |

50 – 1.83 (1.86 – 1.83) |

| No. of observed reflections | 532757 (62641) | 521742 (106608) |

| Redundancy | 8.5 (8.4) | 4.9 (4.8) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (99.7) | 99.7 (98.8) |

| I/sigma(I) | 15.3 (1.3) | 16.9 (1.2) |

| Rmerge (%)b | 13.2 (95.7) | 11.2 (93.1) |

| CC1/2c | 0.99 (0.82) | 0.99 (0.74) |

| Refinementd | ||

| Rwork (%) | 20.1 | 19.1 |

| Rfree (%) | 23.1 | 21.9 |

| RMSD bond length (Å)e |

0.007 | 0.007 |

| RMSD bond angles (°) |

0.938 | 0.829 |

| Ramachandran statisticsf | ||

| Preferred (%) | 96.4 | 98.2 |

| Allowed (%) | 3.0 | 1.7 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | ||

| Protein/atoms | 46.8/5191 | 33.0/7796 |

| Zn/atoms | 68.6/1 | 28.3/3 |

| Ligands/atoms | 57.59/44 | 46.5/15 |

| Solvent/atoms | 49.5/422 | 38.0/812 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

Rmerge =ΣhklΣi |Ii(hkl)-〈I(hkl)〉|/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl), in which the sum is over all the i measured reflections with equivalent miller indices hkl; 〈I(hkl)〉 is the averaged intensity of these i reflections, and the grand sum is over all measured reflections in the data set.

According to Karplus and Diederichs.30

All positive reflections were used in the refinement.

According to Engh and Huber.31

Calculated by using MolProbity.32

The essential residues involved in the ACMSD-catalyzed reaction are Arg51 and Arg239* (* denotes a residue from a neighboring subunit), with each Arg binding a carboxylic group of the substrate,15 and His228, which functions as an active site acid/base catalyst.13 Comparing the ligand-free and ligand-bound structures, the three Zn-binding histidine residues, as well as His228 and Arg239* in the diflunisal-bound structure show no conformation change. Thus, the inhibitory mechanism may involve the competitive binding of diflunisal to the substrate (ACMS) binding site. However, the diflunisal-bound structure reveals significantly distinct protein-ligand interactions than previously observed ligand-bound structures,14, 17 or than those predicted in our virtual screen (Scheme 1C, Figure SI–2). As shown in Figure 2B, Arg51, and Arg247* rotate from the active site pocket toward the outside and form salt bridges with the carboxylate group of diflunisal. Moreover, upon diflunisal binding, the side- chain of Trp194 flips over, while Phe297 and Leu299 also move closer to the ligand, indicating a dynamic nature of these residues upon the ligand binding. The backbone of Leu299 forms an H-bond with the hydroxyl group of diflunisal at 3.2 Å, and Phe297 engages in a π-π stacking interaction with the fluorinated phenyl (B) ring of diflunisal (Figure 2A). These experimentally determined protein-ligand interactions rationalize why changing the orientation of B ring (13) weakened the inhibitory activity. Specifically, binding of diflunisal induced two loop regions consisting of residues of 47–53 (loop β3*)11 and 295–300 to move towards the active site (Figure 2C). The salt bridge formed between the carboxylate group with Arg51 and Arg247*, as well as the H-bond between the hydroxyl group of the A ring and the backbone of Leu299, agree well with the SAR data, which found that both groups are essential for inhibiting hACMSD (Table 2). Moreover, our kinetic analysis indicated that diflunisal is a competitive inhibitor of hACMSD, with a Ki value of 2.56 ± 0.56 μM (Figure 2D). The competitive inhibition mode is consistent with the structural findings.

The diflunisal-bound ACMSD structure represents a new inhibitor binding-mode for ACMSD, but aligns with well our predicted substrate-binding mode described in previous studies (Scheme 3).15 Specifically, the ligand does not engage the active site zinc center. This mode is characterized by two active site arginines interacting with the carboxylate groups of the ligand, preventing it from directly ligating the zinc ion, and by doing so, retaining the zinc-bound hydroxide to activate the substrate. As described above, the ligand-binding process also invokes loop movement in the active site. The ligand-interacting residues, Arg47, Arg243*, Phe294, and Leu296, are the conserved residues in human ACMSD (Figure S1).

Scheme 3.

The proposed binding mode of ACMS in active site of ACMSD (PDB entry: 4IH3).

Moreover, the structure of ACMSD in complex with isosteric analog 11 was obtained by soaking the inhibitor to the protein crystals. The structure was refined to 1.83 Å resolution. In principle, compound 11 and diflunisal bind to ACMSD similarly, though some noticeable differences were observed. The density map in Figure 3A shows how 11 binds to ACMSD in the active site. Upon binding of 11, the conformations of Arg51, Arg247*, and Trp194 adopt similar orientations as those were observed in the diflunisal-bound ACMSD structure. However, the orientation of A ring was rotated approximately 45° and was further away from the active site pocket compared to the diflunisal-bound ACMSD complex (Figure 3B). Although Arg247* engaged 11 at 3.0 Å, the distance of Arg51 to 11 was circa 5 Å, indicating a weaker interaction with this residue.

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of ACMSD in complex with synthetic compound 11 (PDB entry: 7K13). A) The electron density maps of 2Fo - Fc (gray) and omit Fo - Fc (marine) of 11 are contoured at 1.0 and 2.5 σ, respectively. B) A superimposed structural illustration showing the binding modes of diflunisal (yellow sticks) and 14 (cyan sticks).

4. Improvement of the inhibition of diflunisal derivatives

Based on the initial round of the SAR data, inhibitory assays, and structural information, a second generation of inhibitors was designed with a conserved salicylate A ring, but with further modifications of the B ring to improve the inhibitory effect (Table 4, compounds 16–23, 26–27). These diflunisal derivatives were generally designed to probe nearby hydrophobic contacts and the H-bond network in the ligand-binding pocket to engage the side-chain amide interactions. We synthesized 16–17 via Suzuki cross-coupling reactions of salicylate 14 with cycloalkenylboronic acids (Scheme 4A), and reduction of the cycloalkenes using Pd/C/H2 afforded the corresponding cycloalkanes (18–19). Tricyclic compounds 20–23 and intermediates 24–25 were also generated from Suzuki cross-coupling reactions (Scheme 4B–C). From intermediates 24 and 25, reductive cleavage of the benzyl ether and reduction of the aldehyde afforded alcohol-containing derivatives 26 and 27, respectively.

Table 4.

Inhibition of the synthetic diflunisal derivatives

|

The IC50 value of TES-102519 was determined under the same condition as other compounds in this study (See Material and Methods).

Scheme 4.

Preparation of compounds 16–23 and 26–27.

As described earlier, an HPLC-based assay was devised to quickly determine whether the new diflunisal derivatives would inhibit ACMSD activity (Table S2). Among 16 to 27, all of these synthetic diflunisal derivatives showed significant inhibition with the exception of 26 showing a modest inhibition. We then measured the IC50 values of these compounds and summarized in Table 4. The results show several trends. Compared to diflunisal (1), derivatives 7 and 8 that lacked the para- or ortho-fluorine atoms displayed ~3-fold lower IC50 values, indicating that the para fluorine atom disfavors inhibition and the ortho fluorine atom minimally influences inhibition. Bicyclic derivatives 16–19 showed comparable or higher IC50 values that diflunisal, resulting from a similar binding mode of 11 and diflunisal (1) in ACMSD (Figures 2–3). Taking 10, 17, and 19 together, the IC50 values increase with the degree of saturation of B ring. This observation indicates that the aromaticity and planarity of the B ring is beneficial for the inhibition, potentially though π-π or π-charge interactions with Phe297 (as shown in Figure 2B). The comparison of 16 and 18 also supports this understanding. The bulkier tricyclic derivatives, 20–23, displayed lower IC50 values than diflunisal. Among them, naphthyl derivative 22 displayed the lowest IC50 value of 1.32 ± 0.07 μM, though at a higher concentration (IC50 = 31 μM), this compound also inhibited the anti-apoptotic MLC-1 protein.33 In this case, the bulkier group may improve hydrophobic interactions that, in turn, increase inhibitory activity. In an attempt to engage a backbone amide, the 3-position of the B ring was substituted with a methanol group (27). The compound inhibited the enzyme with comparable IC50 value to diflunisal. Further elongation of the methylene chain (26) weakened the inhibitory activity.

Discussion

Elucidation of the mechanism of inhibition

Inhibition of ACMSD has been recently studied as a means of elevating the NAD+ levels and further improving mitochondrial function as well as alleviating some diseases such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, steatohepatitis, acute kidney injury, and chronic kidney diseases.3 TES-1025 inhibits ACMSD through multiple functional groups in the SAR study, however, the details regarding the mechanism of interaction remain speculative.19 Prior to this work, the structurally determined inhibitor binding mode involved a direct interaction between the metal and ligand.14, 17 Typically, direct binding between a ligand and a metal center could inactivate other metalloproteins, resulting in undesirable in vivo effects. Therefore, the finding of a group of inhibitors that bind the active site of ACMSD without coordinating the catalytic zinc ion is a significant advance.

In this study, an FDA-approved drug, diflunisal, inhibits ACMSD activity by triggering two loop regions to move toward diflunisal where Arg51, Phe297, and Leu299 are located (Figure 2). Arg51 and Arg239* have been previously demonstrated to interact with the carboxylate group of the substrate during decarboxylation (Scheme 3).15 Therefore, it is proposed that diflunisal inhibits ACMSD activity through competitive inhibition, which is supported by the inhibition assay (Figure 2D). Interestingly, Arg247*, not Arg239*, from the adjacent subunit moves to the active site and forms a salt-bridge with the carboxylate group of diflunisal. This arginine residue, Arg247*, is not involved in ACMS binding and does not play a direct role in catalysis. Thus, its involvement in the inhibitor binding through structural determination deepens the molecular understanding of the ACMSD-ligand interaction mechanism. The ability of diflunisal to recruit Arg247* is unexpected. Predictably, the binding of diflunisal to the active site depends on the oligomeric status of ACMSD, like previously found for ACMS.14–16 In the new binding mode, the molecule of diflunisal is more than 7 Å from the Zn ion (Figure 2). Since diflunisal specifically recognizes conserved residues in the active site without directly chelating the Zn ion and may have potential for further optimizations and drug development. Additionally, diflunisal has already been FDA-approved, which reduces the likelihood for diflunisal and its derivatives to induce concerning levels of toxicity.

Insight of the improved inhibition of the derivatives

Of note, diflunisal (1) and its derivative, 11 (Figures 2 & 3) bind ACMSD in a similar binding mode in which the salicylic acid moiety interacts with Arg51 and Arg 247*. In contrast, the B ring shows relative flexibility due to the weaker hydrophobic interaction. In the ACMSD structure in complex with diflunisal (Figure 2), we notice that the B ring of diflunisal orients toward a hydrophobic cavity (Figure 4) formed by Phe13, Ile43, Met45, Phe50, Val53, Leu57, Thr80, and Val82 in bacterial ACMSD (numbering Leu10, Leu39, Leu40, Phe46, Val49, Cys53, Val76, and Val78 in human ACMSD, respectively). To exploit this hydrophobic cleft, analogs bearing bulkier aromatic ring systems (20–23) displayed improved IC50 values. Specifically, enlarging the B ring from phenyl to naphthalene (22) reduced the IC50 value by one order of magnitude, from 13.5 μM to 1.32 μM, which could result from filling the hydrophobic cavity with the naphthalene ring. In contrast, the higher IC50 value of 23 (8.83 μM) could result from the different orientation of the naphthalene moiety of 23 not fitting as neatly in the hydrophobic pocket. Taken together with another derivative (13), the results indicate the active site cavity has its specific shape to embed in future inhibitor candidates.

Figure 4.

The B ring of diflunisal points to a hydrophobic pocket (PDB entry: 7K12). The hydrophobic residues containing Phe13, Ile43, Met45, Phe50, Val53, Leu57, Thr80, and Val82 are show in cyan. Diflunisal is shown as yellow, red, and cyan sticks for carbon, oxygen, and fluorine, respectively.

Comparing inhibition with the published inhibitors

Diflunisal and PDC both inhibit ACMSD in a competitive manner However, diflunisal has a 6-fold lower Ki value (2.56 ± 0.56 μM) compared with PDC (15.2 ± 0.5 μM), suggesting an improved competitive inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 2, the carboxylate and hydroxyl groups interact with two Arg residues of ACMSD, of which Arg51 is involved in the catalytic reaction. Therefore, diflunisal and ACMS competitively interact with the side-chain of Arg51, which agrees well with the inhibition model indicated in Fig. 2D. Pellicciari et al. developed a new cluster of inhibitors based on multiple rounds of optimization of published crystal structures of ACMSD in complex with DHAP and PDC.19 TES-1025 (Scheme 1) exhibits an IC50 value of 13 nM at the 3-HAA concentration of 10 μM in a coupled assay. In this study, the substrate of ACMSD, ACMS was prepared in a millimolar concentration by an enzymatic method.12, 34 Therefore, ACMS is directly used in the inhibition assay instead of a coupled assay. When ACMS is set at the same concentration of 10 μM as described in Pellicciari et al,19 IC50 value for TES-1025 was measured as 0.078 ± 0.002 μM (Table 4), which is higher in our used method. Nonetheless, this value provides a better comparison with our diflunisal derivatives with our best hits displaying IC50 of 1.32 μM (22) and 3.10 μM (20), although they are 17-fold and 40-fold weaker than TES-1025, respectively. The best hits with lower IC50 values, 20 and 22 were not successfully soaked into ACMSD crystals, even after extensive attempts. However, two complex structures are still informative to reveal the new binding mode, which can be exploited in the design of future analogs.

Expanding the understanding of diflunisal in regulating NAD+ homeostasis

Diflunisal is a derivative of salicylic acid, which is known as a non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug. Very recently, diflunisal is reported to competitively inhibit dihydrofolate reductase.35 It is also a selective inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-226 reported to be responsible for regulating inflammation and pain.36 The elevated cyclooxygenase-2 in some cancer types suggested it is a potential target for cancer therapy. Diflunisal derivatives with 1,2,4-triazoles on the A ring show anti-cancer activity towards the breast cancer cells27 and anti-inflammatory activities.37 The iodo-diflunisal (on A ring) is also a potent amyloid inhibitor.38 Here, we illustrated that diflunisal derivatives with modifications on B ring possess an additional role in the kynurenine pathway for tryptophan degradation as an inhibitor of ACMSD. Since ACMSD inhibitors have been demonstrated to modulate NAD+ homeostasis,3 the results presented in this study suggest that diflunisal and its derivatives may be considered as regulators of NAD+ biosynthesis in the tryptophan-kynurenine degradation pathway. This inhibitory effect of diflunisal and derivatives vs. ACMSD should be further explored in translational repurposing studies, along with other ongoing studies evaluating diflunisal’s potential for other indications.3, 19, 26, 35

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Picolinic acid, quinolinic acid, acetonitrile and trifluoroacetic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The selected FDA-approved drugs were purchased from commercial sources (See SI for specific sources and purity data). PdCl2(NH2CH2COOH)2 was prepared according to the literature.29 2’,4’-difluoro-4-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (diflunisal, 1), 2’,4’-difluoro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (2), 2’,4’-difluoro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-ol (3) were acquired from commercial sources and used without further purification. Their identity was confirmed using 1H NMR. Unless otherwise noted, reagents were purchased from various commercial sources and used as received. All tested compounds, whether synthesized or purchased, were >95% pure as deemed by UPLC analysis. H2O, used for synthetic reactions, was distilled under an atmosphere of N2 prior to use.

Protein preparation

The human ACMSD was expressed in Escherichia coli with a co-expression chaperone GroEL-GroES in the M9 growth medium.14 The isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside and L-arabinose were used to induce ACMSD and chaperone, respectively. The 50 μM ZnCl2 was added into the medium after induction to maintain the high metal-occupancy in enzymes. The protein was purified by a nickel affinity chromatographic column from the cell lysate, and further purified on a Superdex 200 column with a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.0 and 5% glycerol. The proteins were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for the inhibition assay.

Methods to screen FDA-approved drugs

FDA-approved drugs were downloaded from Drugbank39 and prepared using Ligprep by Schrodinger23 to generate ionization states around neutral pH, as well as to generate tautomers and stereoisomers (when chirality was not specified). The structure of ACMSD (PDB entry: 4IH3)14 was downloaded and prepared using the protein preparation wizard by Schrodinger23 to add hydrogens, identify metal binding sites, identify ionization states, optimize hydrogen binding, and then minimize the structure into the Schrodinger’s energy function. Because the asymmetric unit had 6 chains, that is 3 dimers with 6 separate active sites, the minimized structure was separated into three dimers and for each dimer, a receptor docking grid was created for each of the two active sites.

The library was screened against each of the receptors using Glide20–23 at HTVS, SP, and XP precisions, advancing the top 20% scoring compounds of the compounds that were able to be successfully docked at HTVS precision and the top 50% of those docket at SP precision. Poses with a score better than –10 kcal/mol at XP precision were further refined using Prime MMGBSA,23–25 allowing flexibility of any residue within 8 Å of the ligand. The hits from the virtual screen were filtered for PAINS (PMID 20131845) using Canvas by Schrodinger.23, 40, 41

General Synthetic Considerations

Air- and moisture-sensitive reactions were carried out in oven-dried one-dram vials sealed with PTFE-lined septa or glassware sealed with rubber septa under an atmosphere of dry nitrogen. PTFE syringes equipped with stainless-steel needles were used to transfer air- and moisture-sensitive liquid reagents. Reactions were stirred using teflon-coated magnetic stir bars, and elevated temperatures were maintained using thermostat-controlled heating mantles. Organic solvents were removed using a rotary evaporator with a diaphragm vacuum pump. Thin-layer analytical chromatography was performed on silica gel UNIPLATE Silica Gel HLF UV254 plates, and spots were visualized by quenching of ultraviolet light (λ = 254 nm). Purification of products was accomplished by automated flash column chromatography on silica gel (VWR Common Silica Gel 60 Å, 40–60 μm).

NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX 500 MHz (1H at 500 MHz, and 19F at 471 MHz,) or a Bruker AVIIIHD 400 MHz (13C at 126 MHz) nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer. 1H NMR spectra were calibrated against the peak of the residual CHCl3 (7.26 ppm), DMSO (2.50 ppm), acetonitrile (1.94 ppm), or methanol in the solvent (4.78 and 3.31 ppm). 13C NMR spectra were calibrated against the peak of the residual CHCl3 (77.2 ppm) or DMSO (40.0 ppm), acetonitrile (118.7 and 1.3 ppm), or methanol in the solvent (49.0 ppm). NMR data are represented as follows: chemical shift (ppm), multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, p = pentet, m = multiplet), coupling constant in Hertz (Hz), integration. High-resolution mass determinations were obtained by electrospray ionization (ESI) on a Waters LCT Premier™ or an Agilent 6550 iFunnel Q-ToF mass spectrometer. Infrared spectra were measured on a Perkin Elmer Spectrum Two Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer by drying samples on a diamond ATR sample base plate. Uncorrected melting points were measured on a Thomas Hoover Uni-melt Capillary Melting Point apparatus. Retention times for liquid chromatography were recorded with a Waters H Class Plus Acquity UPLC equipped with a PDA eλ detector or Agilent 1260 Infinity II equipped with a DAD WR detector. Chromatography was conducted using a 0.7 mL/min flow rate at 40 °C and Acquity UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm) column fitted with a C18 guard cartridge. Two mobile phase solutions were used: solution A 0.1% formic acid in water and solution B was acetonitrile. Method A: The elution program consisted of a linear gradient starting at 98% A 0.5 min following injection to 2% A over 2.7 min. Method B: The elution program consisted of a linear gradient starting at 98% A 0.5 min following injection to 2% A over 6.5 min.

General Procedure A (Suzuki Miyaura coupling):29

A 100 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a stirring bar was charged with 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (1.1 g, 5.0 mmol), boronic acid (6.0 mmol), PdCl2(NH2CH2COOH)2 (16 mg, 50 μmol), K2CO3 (2.1 g, 15 mmol) and H2O (20 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for ~24 h. The product precipitated upon acidification of the reaction mixture (pH ~2–3, caution exothermic!), and the precipitate was collected by filtration. The solid collected was suspended in water (~30 mL), and the pH was adjusted to 8–10 by adding 6M NaOH dropwise (caution exothermic!). This basic mixture was heated to ~95 °C to re-dissolve the solids (more water added, as needed), and the resulting solution was filtered while hot using a fritted glass funnel. The filtrate was acidified with 1N HCl (pH ~3–4, caution exothermic!) to precipitate the desired product. The product was dissolved in EtOAc, and dried with Na2SO4. After filtration, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, 1H NMR and UPLC analysis confirmed the identity and purity of the products. All products were dried in high-vacuum for >6 h before testing.

2’,4’-Difluoro-3-(hydroxymethyl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-ol (4)

This compound was prepared according to previous literature precedent:42 An oven-dried two-neck round-bottom flask equipped with a stirring bar under nitrogen was charged with LiAlH4 (0.30 g, 8.0 mmol). The reaction flask was cooled to 0 °C, and dry THF (10 mL) was added via a syringe. Next, a solution of diflunisal (0.50 g, 2.0 mmol) in dry THF (~5 mL) was added dropwise, and then the reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. Next, the reaction mixture was refluxed for several hours until the starting material disappeared (TLC). After cooling the reaction to room temperature, the reaction was cooled to 0 °C and quenched by slow addition of 1M HCl (5 mL). After gas evolution ceased, the product was transferred to a separation funnel, and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 25 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with NaCl(sat) (1 × 25 mL) dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated to afford the title compound as a colorless oil (0.45 g, 95%). Spectroscopic data agreed with the previous report.42 HPLC purity 96.18%; Rt = 4.619 min (Method B).

Methyl 2’,4’-difluoro-4-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylate (5)

An oven-dried two-neck flask equipped with a stirring bar, a gas outlet attached to the Schlenk line and a rubber septum under nitrogen was charged with diflunisal (0.50 g, 2.0 mmol) and CH2Cl2 (10 mL). The resulting suspension was cooled using an ice-water bath, and oxalyl chloride (0.19 mL, 2.2 mmol) was added. Next, DMF (10 μL) was added dropwise (caution: rapid evolution of noxious gases). After stirring at low temperature for 10 min, the solution was stirred at room temperature until the evolution of gas ceased (mixture turned into a clear solution). Next, the reaction mixture was cooled using an ice-water bath, and NH3 in MeOH solution (2M, 2.0 mL, 4.0 mmol of NH3) was added dropwise. After 10 min stirring at low temperature and 6h at room temperature, the reaction was quenched with 1M HCl(aq) (10 mL) and transferred to a separation funnel. The phases were separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 25 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with NaCl(sat) (1 × 25 mL), dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. Purification by flash column chromatography (20% of EtOAc in hexanes) afforded the title compound as a colorless oil (0.40 g, 75%). Spectroscopic data agreed with the previous report.42 HPLC purity 99.99%; Rt = 6.141 min (Method B).

2’,4’-Difluoro-4-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxamide (6)

A 100 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a stirring bar was charged with 5 (0.19 g, 0.72 mmol), and MeOH (10 mL). Next, a NH4OH (7 mL, ~30% NH3 in H2O) was added, and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for ~24 h. Next, the volatiles were evaporated under reduced pressure, and the aqueous residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 25 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with NaCl(sat) (1 × 25 mL), dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. Purification by flash column chromatography (20% to 40% of EtOAc in hexanes) afforded the title compound as a colorless oil (0.15 g, 80%). Spectroscopic data agreed with the previous report.42 HPLC purity 99.99%; Rt = 4.904 min (Method B).

4’-Fluoro-4-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (7)

General procedure A was followed using 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (1.1 g, 5.0 mmol), (4-fluorophenyl)boronic acid (0.84 g, 6.0 mmol), PdCl2(NH2CH2COOH)2 (16 mg, 50 μmol), K2CO3 (2.1 g, 15 mmol) and H2O (20 mL). Workup and re-precipitation afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (0.79 g, 68%). Spectroscopic data agreed with the previous report.29 HPLC purity 99.99%; Rt = 4.958 min (Method B).

2’-Fluoro-4-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (8)

General procedure A was followed using 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (1.1 g, 5.0 mmol), (2-fluorophenyl)boronic acid (0.84 g, 6.0 mmol), PdCl2(NH2CH2COOH)2 (16 mg, 50 μmol), K2CO3 (2.1 g, 15 mmol) and H2O (20 mL). Workup and re-precipitation afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (0.78 g, 67%). Spectroscopic data agreed with the previous report.43 HPLC purity 99.99%; Rt = 4.901 min (Method B).

3’-Fluoro-4-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (9)

General procedure A was followed using 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (1.1 g, 5.0 mmol), (3-fluorophenyl)boronic acid (0.84 g, 6.0 mmol), PdCl2(NH2CH2COOH)2 (16 mg, 50 μmol), K2CO3 (2.1 g, 15 mmol) and H2O (20 mL). Workup and re-precipitation afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (0.59 g, 51%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.08 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.47 – 7.34 (m, 2H), 7.28 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H), 7.06 – 6.99 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 173.3, 165.7 (d, J = 244.4 Hz), 163.8, 163.1, 143.7, 143.6, 135.1, 132.1 (d, J = 2.6 Hz), 131.7 (d, J = 8.2 Hz), 129.6, 123.4 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 118.9, 114.6 (d, J = 21.1 Hz), 114.1 (d, J = 22.0 Hz). 19F NMR (470 MHz, MeOH) δ −116.46 – −116.63 (m). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]− calcd for C13H8FO3 231.0463; found 231.0464 (0.6 ppm). HPLC purity 99.99%; Rt = 4.928 min (Method B).

4-Hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (10)

General procedure A was followed using 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (1.1 g, 5.0 mmol), phenylboronic acid (0.72 g, 6.0 mmol), PdCl2(NH2CH2COOH)2 (16 mg, 50 μmol), K2CO3 (2.1 g, 15 mmol) and H2O (20 mL). Workup and re-precipitation afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (0.61 g, 57%). Spectroscopic data agreed with the previous report.43 HPLC purity 99.99%; Rt = 4.861 min (Method B).

2-hydroxy-5-(thiophen-3-yl)benzoic acid (11)

Ethyl 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzoate was prepared according to previous literature precedent. Ethyl 5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzoate (245 mg, 1.0 mmol), 3-thiopheneboronic acid (128 mg, 1.0 mmol), NaHCO3 (210 mg, 2.5 mmol), and Pd(PPh3)3 (29 mg, 25 μmol) were added to a 25 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed under Ar atmosphere. Diglyme (5.2 mL) and H2O (2.6 mL) were injected, and the reaction mixture was heated to 105 °C and stirred for 24 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL), neutralized with 1 N HCl (2.5 mL), and filtered through a pad of celite. The mixture was washed with H2O (10 mL) and brine (10 mL), and the organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (42 mg, 13%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.06 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.62 (s, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 2.51 – 2.48 (m, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.3, 160.7, 140.8, 133.8, 127.7, 127.6, 127.1, 126.4, 120.4, 118.1, 113.9. IR (film) 3681, 2982, 2866, 2844, 1667, 1033 cm−1. Melting Point 214.1 – 215.0 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C11H7O3S 219.0116; found 219.0102 (6.4 ppm). HPLC purity 99.57%; Rt = 2.169 min (Method A).

3-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid (13)

4-Bromosalicylic acid (217 mg, 1.0 mmol), phenylboronic acid (146 mg, 1.2 mmol), K2CO3 (415mg, 3.0 mmol), and PdCl2(Gly)2 (6.6 mg, 20 μmol) were added to a 25 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed under an Ar atmosphere. H2O (5.0 mL) was injected, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 35 °C for 1.5 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL), neutralized with 1 N HCl (3.0 mL), and filtered through a pad of celite. The mixture was washed with H2O (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), and the organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (150 mg, 70%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.86 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.42 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.25 – 7.23 (m, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.2, 161.9, 147.6, 139.2, 131.3, 129.5, 129.1, 127.4, 118.2, 115.2, 112.4. IR (film) 3052, 2847, 2557, 1777, 1650, 759, 699 cm−1. Melting Point 203.8 – 204.7 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C13H9O3 213.0552; found 213.0566 (6.6 ppm). HPLC purity 99.99%; Rt = 2.336 min (Method A).

Lead Optimization: Synthesis of Diflunisal 16 – 29 Derivatives and Intermediates

5-(cyclopent-1-en-1-yl)-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (16)

5-Bromosalicylic acid (110 mg, 0.50 mmol), 1-cyclopenteneboronic acid (75 mg, 0.67 mmol), and Pd(PPh3)3 (58 mg, 50 μmol) were added to a 25 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed under Ar atmosphere. EtOH (2.1 mL), toluene (4.2 mL) and 2 M K2CO3 aq. (4.2 mmol, 2.1 mL) were injected, and the reaction mixture was heated to 80 °C and stirred for 24 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL), neutralized with 1 N HCl (4.2 mL), and filtered through a pad of celite. The mixture was washed with H2O (10 mL), and brine (10 mL). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (20 mg, 20%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.90 (s, 1H), 11.21 (s, 1H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.07 (s, 1H), 2.31 (s, 2H), 2.15 (s, 2H), 1.74 – 1.67 (m, 2H), 1.62 – 1.53 (m, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.4, 160.4, 135.0, 133.4, 132.5, 126.2, 123.7, 117.5, 113.0, 27.1, 25.7, 23.0, 22.1. IR (film) 3681, 2959, 2865, 2844, 2619, 1651, 1445, 1199, 691, 470 cm−1. Melting Point 196.3 – 197.1 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C12H11O3 203.0708; found 203.0713 (2.5 ppm). HPLC purity 99.71%; Rt = 2.428 min (Method A).

4-hydroxy-2’,3’,4’,5’-tetrahydro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (17)

5-Bromosalicylic acid (108 mg, 0.50 mmol), 1-cyclohexeneboronic acid (84 mg, 0.67 mmol), and Pd(PPh3)3 (58 mg, 50 μmol) were added to a 25 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed under Ar atmosphere. EtOH (2.1 mL), toluene (4.2 mL) and 2 M K2CO3 aq. (4.2 mmol, 2.1 mL) were injected, and the reaction mixture was heated to 80 °C and stirred for 24 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL), neutralized with 1 N HCl (4.2 mL), and filtered through a pad of celite. The mixture was washed with H2O (10 mL), and brine (10 mL). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (20 mg, 18%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.99 (s, 1H), 11.25 (s, 1H), 7.75 (s, 0H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.16 (s, 1H), 2.62 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.46 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 1.95 (p, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.3, 160.7, 141.0, 133.4, 128.1, 127.0, 125.0, 117.7, 113.1, 33.3, 33.2, 23.3. IR (film) 3681, 2935, 2863, 2829, 2616, 2527, 1647, 1205, 675 cm−1. Melting Point 186.1 – 187.6 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C13H13O3 217.0865; found 217.0857 (3.7 ppm). HPLC purity 99.91%; Rt = 2.524 min (Method A).

5-cyclopentyl-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (18)

5-(cyclopent-1-en-1-yl)-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (16) (580 mg, 2.8 mmol) and 5% Pd/C (30 mg, 0.28 mmol) were added to a 1-dram vial, which was sealed with a PTFE-lined septum. EtOH (3.1 mL) was injected, and the vial was placed under H2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 3 days, and the mixture was diluted with MeCN (5.0 mL) and filtered through a pad of celite. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (36 mg, 6%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.62 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 2.92 (tt, J = 9.9, 7.4 Hz, 1H), 1.98 (dddd, J = 16.8, 7.7, 4.2, 1.8 Hz, 2H), 1.80 – 1.69 (m, 2H), 1.68 – 1.56 (m, 2H), 1.46 (dddd, J = 18.3, 12.1, 6.9, 2.0 Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.4, 159.8, 136.7, 134.8, 128.4, 117.4, 113.2, 44.7, 34.6, 25.4. IR (film) 3681, 3231, 2943, 2871, 2610, 1934, 1661, 1446, 1219, 678 cm−1. Melting Point 146.5 – 147.1 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C12H13O3 205.0870; found 205.0862 (3.9 ppm). HPLC purity 96.99%; Rt = 2.463 min (Method A).

5-cyclohexyl-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (19)

4-hydroxy-2’,3’,4’,5’-tetrahydro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (17) (40 mg, 0.18 mmol) and 5% Pd/C (2.0 mg, 18 μmol) were added to a 1-dram vial, which was sealed with a PTFE-lined septum. EtOH (0.20 mL) was injected, and the vial was placed under H2 atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 3 days, and the mixture was diluted with MeCN (2.0 mL) and filtered through a pad of celite. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (20 mg, 50%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.60 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 2.44 (dtd, J = 11.4, 6.8, 6.1, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 1.80 – 1.72 (m, 4H), 1.71 – 1.65 (m, 1H), 1.40 – 1.28 (m, 4H), 1.22 (ddt, J = 12.6, 6.5, 3.3 Hz, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.4, 159.8, 138.6, 134.7, 128.0, 117.4, 113.1, 43.1, 34.5, 26.8, 26.0. IR (film) 3681, 3255, 2982, 2922, 2854, 2624, 2581, 1918, 1663 cm−1. Melting Point 148.7 – 149.6 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C13H15O3 219.1021; found 219.1010 (5 ppm). HPLC purity 97.41%; Rt = 2.600 min (Method A).

4-hydroxy-[1,1’:3’,1”-terphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (20)

5-Bromosalicylic acid (217 mg, 1.0 mmol), 3-biphenylboronic acid (238 mg, 1.2 mmol), K2CO3 (414 mg, 3.0 mmol), and PdCl2(Gly)2 (3.3 mg, 10 μmol) were added to a 10 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed under Ar atmosphere. H2O (5.0 mL) was injected, and the reaction mixture was heated to 35 °C and stirred for 1.5 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL), neutralized with 1 N HCl (1.5 mL), and filtered through a pad of celite. The mixture was washed with H2O (10 mL), and brine (10 mL). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (44 mg, 15%) which was heated in MeOH at 70 °C to remove excess boron-containing side products, after which the residual MeOH was removed in vacuo. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.10 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.57 – 7.53 (m, 2H), 7.49 (dd, J = 13.3, 7.6 Hz, 3H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.2, 163.2, 141.7, 141.3, 140.9, 130.7, 129.9, 129.4, 128.8, 128.6, 127.9, 127.3, 125.4, 125.0, 124.7, 120.6, 117.1. IR (film) 3681, 3032, 2982, 2867, 2844, 1668, 1436, 1201 cm−1. Melting Point 189.2 – 190.1 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C19H13O3 289.0865; found 289.0870 (1.7 ppm). HPLC purity 99.99%; Rt = 2.676 min (Method A).

1-benzyl-3-bromobenzene (28)

THF (2.0 mL) was added to a one-dram vial containing phenylmagnesium iodide (228 mg, 1.0 mmol) which was placed in a −20 °C ice bath. Allowed to cool to −20 °C, 3-bromobenzaldehyde (180 mg, 1.0 mmol) was injected dropwise, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 2 h. The mixture was neutralized with 1N HCl (1.0 mL) and diluted with EtOAc (2.0 mL). The mixture was washed with H2O (2.0 mL), and brine (1.0 mL). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Normal-phase chromatography (Hexanes : EtOAc, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (110 mg, 42%).

The intermediate alcohol (3-bromophenyl)(phenyl)methanol (263 mg, 1.0 mmol) and DCM (0.5 mL) were added to an oven-dried one-dram vial. InCl3 (11 mg, 50 μmol), Me2SiHCl (114 mg, 1.2 mmol), and DCM (1.0 mL) were added to a separate oven-dried one-dram vial. The (3-bromophenyl)(phenyl)methanol solution (0.50 mL) was injected dropwise over 5 min., and the reaction mixture stirred at rt for 2 h under N2 atmosphere. The mixture was washed with H2O (2.0 mL), diluted with Et2O (2.0 mL), and filtered through a pad of celite. The solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Normal-phase chromatography (Hexanes : EtOAc, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (122 mg, 49%). Spectroscopic data agreed with the previous report.44

(3-benzylphenyl)boronic acid (29)

1-Benzyl-3-bromobenzene (261 mg, 1.1 mmol) and THF (4.2 mL) were added to an oven-dried 25 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed in a −76 °C ice bath under N2 atmosphere. Allowed to cool to −76 °C, 2.5 M n-BuLi (0.51 mL, 1.2 mmol) was injected dropwise. The mixture was allowed to stir at −76 °C for 1 h. Triisopropyl borate (0.64 mL, 2.8 mmol) was injected dropwise, and the reaction mixture was stirred at −76 °C for 30 min. The mixture was allowed to warm to rt and then neutralized with 1 N HCl (1.2 mL). The mixture was diluted with Et2O (5.0 mL) and washed with H2O (5.0 mL) and brine (5.0 mL). The solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Normal-phase chromatography (Hexanes : EtOAc, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (135 mg, 60%). Spectroscopic data agreed with the previous report.45

3’-benzyl-4-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (21)

5-Bromosalicylic acid (115 mg, 0.53 mmol), (3-benzylphenyl)boronic acid (135 mg, 0.64 mmol), K2CO3 (220 mg, 1.6 mmol), and PdCl2(Gly)2 (17 mg, 53 μmol) were added to a 10 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed under Ar atmosphere. H2O (2.7 mL) was injected, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 1.5 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL), neutralized with 1 N HCl (1.5 mL), and then filtered through a pad of celite. The mixture was washed with H2O (10 mL), and brine (10 mL). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (20 mg, 12%).1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.99 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (dd, J = 12.3, 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (t, 1H), 7.35 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.31 – 7.26 (m, 5H), 7.19 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 0H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 4.02 (s, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.2, 164.0, 161.1, 159.1, 142.5, 141.8, 140.1, 139.7, 134.3, 133.5, 131.7, 131.5, 129.6, 129.5, 129.2, 129.2, 128.9, 128.4, 128.0, 127.7, 127.4, 127.0, 127.0, 126.4, 124.4, 124.3, 119.2, 118.3, 116.0, 41.6. IR (film) 3681, 2981, 2844, 1676, 1033 cm−1. Melting Point 219.1 – 220.2 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C20H15O3 303.1021; found 303.1018 (1 ppm). HPLC purity 98.81%; Rt = 2.711 min (Method A).

2-hydroxy-5-(naphthalen-1-yl)benzoic acid (22)

5-Bromosalicylic acid (217 mg, 1.0 mmol), 1-napthalene boronic acid (206 mg, 1.2 mmol), K2CO3 (414 mg, 3.0 mmol), and PdCl2(Gly)2 (33 mg, 0.10 mmol) were added to a 25 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed under Ar atmosphere. H2O (5.0 mL) was injected, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 1.5 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL), neutralized with 1 N HCl (3.0 mL), and filtered through a pad of celite. The mixture was washed with H2O (20 mL), and brine (20 mL). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a purple solid (104 mg, 39%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.00 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.59 – 7.46 (m, 3H), 7.43 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.2, 161.0, 138.7, 137.3, 134.0, 131.5, 131.4, 131.2, 128.9, 128.1, 127.4, 127.0, 126.4, 126.1, 125.5, 117.8, 113.7. IR (film) 3240, 2851, 2602, 2555, 1935, 1738, 1659, 1208 cm−1. Melting Point 224.8 – 225.6 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C17H11O3 263.0708; found 263.0693 (5.7 ppm). HPLC purity 96.08%; Rt = 2.546 min (Method A).

2-hydroxy-5-(naphthalen-2-yl)benzoic acid (23)

5-Bromosalicylic acid (217 mg, 1.0 mmol), 2-napthalene boronic acid (206 mg, 1.2 mmol), K2CO3 (414 mg, 3.0 mmol), and PdCl2(Gly)2 (33 mg, 0.10 mmol) were added to a 25 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed under Ar atmosphere. H2O (5.0 mL) was injected, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 1.5 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL), neutralized with 1 N HCl (3.0 mL), and filtered through a pad of celite. The mixture was washed with H2O (20 mL), and brine (20 mL). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a purple solid (164 mg, 64%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.20 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (s, 1H), 7.98 (ddd, J = 10.9, 8.3, 4.1 Hz, 3H), 7.92 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59 – 7.45 (m, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.29, 161.32, 136.92, 134.31, 133.87, 132.44, 131.30, 129.00, 128.73, 128.56, 127.93, 126.87, 126.40, 125.17, 124.89, 118.31, 114.49. IR (film) 3681, 2982, 2922, 2865, 2845, 1668 cm−1. Melting Point 214.4 – 215.9 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C17H11O3 263.0708; found 263.0698 (3.8 ppm). HPLC purity 98.57%; Rt = 2.533 min (Method A).

4-hydroxy-3’-(2-hydroxyethyl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylate (26)

5-Bromosalicylic acid (89 mg, 0.41 mmol), (3-(2-(benzyloxy)ethyl)phenyl)boronic acid (128 mg, 0.50 mmol), NaHCO3 (105 mg, 1.3 mmol), and PdCl2(Gly)2 (1.3 mg, 4.0 μmol) were added to a 10 mL round bottom flask, which was sealed with a rubber septum, and placed under N2 atmosphere. H2O (5.0 mL) was injected, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 1.5 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10 mL), neutralized with 1 N HCl (3.0 mL), and filtered through a pad of celite. The mixture was washed with H2O (20 mL), and brine (20 mL). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a purple solid (41 mg, 29%).

The intermediate benzyl protected analog 3’-(2-(benzyloxy)ethyl)-4-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (24) (41 mg, 0.12 mmol) and 5% Pd/C (2.5 mg, 0.02 mmol) were added to a 1-dram vial, which was sealed with a PTFE-lined septum. THF (1.2 mL) and AcOH (10 μL) were injected and the vial was placed under an atmosphere of H2. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 3 days, and the mixture was diluted with MeCN (2.0 mL) and filtered through a pad of celite and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (29 mg, 96%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetonitrile-d3) δ 8.09 (s, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.83 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, Acetonitrile-d3) δ 172.6, 161.6, 140.9, 140.2, 134.8, 132.7, 129.5, 129.0, 128.4, 127.8, 124.8, 119.3, 113.7, 63.3, 39.4. IR (film) 3707 2681, 2952, 2892, 2864, 2844, 2521, 2203, 2025, 1651 cm−1. Melting Point > 250 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C15H14O4 257.0814; found 257.0800 (3.1 ppm). HPLC purity 96.37%; Rt = 1.932 min (Method A).

4-hydroxy-3’-(hydroxymethyl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (27)

3’-Formyl-4-hydroxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (25) (100 mg, 0.41 mmol) and NaBH4 (23 mg, 0.62 mmol) were added to a 1-dram vial, which was sealed with a PTFE-lined septum. Cold THF (1.9 mL, 0 °C) was injected into the reaction mixture, which was placed in a 0 °C ice bath. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C and stirred for 5 h. The mixture was quenched with 1N HCl (1.0 mL) and allowed to warm to rt. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (10.0 mL), and the solution was washed with H2O (5.0 mL) and brine (5.0 mL). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Reversed-phase chromatography (0.1% AcOH in H2O : MeCN, 1:0 → 0:1) afforded the title compound as a colorless solid (41 mg, 39%) which was heated in MeOH at 70 °C to remove excess boron-containing side products, after which the residual MeOH was removed in vacuo. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.73 (s, 4H), 8.04 (s, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (s, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 5.24 (s, 1H), 4.56 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.2, 161.1, 143.8, 139.3, 134.1, 131.7, 129.2, 128.3, 125.6, 124.9, 124.6, 118.2, 114.2, 63.3. IR (film) 3681, 3364, 2973, 2866, 2844, 2596, 1672 cm−1. Melting Point 147.4 – 148.9 °C. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M - H]- calcd for C14H11O4 243.0657; found 243.0645 (4.9 ppm). HPLC purity 97.33%; Rt = 1.818 min (Method A).

Quantitation of decay products by HPLC

ACMS was synthesized by enzymatic method described previously.34 The candidates of ACMSD inhibitors were solved in either water or DMSO as stock solutions. The reaction mixture contains 100 nM human ACMSD, 40 μM ACMS and 1 mM candidates and incubates under room temperature overnight to make sure the complete conversion to the counterpart decay products. The mixture solution was ultrafiltered to remove proteins and injected into an InertSustain C18 column (GL Science Inc.) on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC combined with a diode-array detector (Sunnyvale, CA). Then the compounds of PA and QUIN were separated and detected with a mobile solution containing 2.5% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The PA and QUIN were calibrated with gradient concentrations.

IC50 and inhibition constant measurement

The serial dilution of the diflunisal derivatives was pre-mixed in the buffer containing 50 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.0 and 10 mM NaCl. The human ACMSD activity was measured by monitoring the decreasing rate of the absorbance of substrate, ACMS on 360 nm (ε360 of 47,500 M−1 cm−1) with an Agilent 8453 diode-array spectrometer at room temperature.11 The concentration of substrate, ACMS is 10 μM to keep the same as the previous reported.12, 19 The IC50 values was obtained as the mid-point concentration c by fitting the Boltzmann function.

The Michaelis-Menten profile of ACMSD was measured with increasing diflunisal concentration of 1, 1.3, 5, 10, 16, and 22.5 μM. The data were globally fitted to determine the inhibition model and the inhibition constant.

Crystallization, data collection, processing, and refinement

ACMSD from Pseudomonas fluorescens was crystalized under a modified condition,11, 16 which contains 0.2 M ammonium citrate pH 6.4 and 15% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 3,350. The crystals were soaked with diflunisal derivatives for 10 to 30 minutes prior to flash-cool in liquid nitrogen. The diffraction data sets were collected at SSRL and SBC and further processed and scaled by HKL-3000.46 The complexed structures were solved by the method of molecular replacement by using ligand-free ACMSD (PDB entry 2HBV) as the template and refined by using Phenix 1.10.1–215547 and Coot 0.8.3.48 PyMOL was utilized in drawing structural figures.49

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in whole or part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants MH107985, GM108988 (to A.L.), and GM124661 (to R.A.A.), and the Lutcher Brown Distinguished Chair Endowment fund (to A.L.). Support for the NMR Instrumentation was provided by NIH Shared Instrumentation Grants S10OD016360 and S10RR024664, NSF Major Research Instrumentation Grants 9977422, 1625923, and NIH Center Grant P20GM103418. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- ACMS

α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde

- ACMSD

ACMS decarboxylase

- 2-AMS

α-aminomuconate semialdehyde

- BEH

ethylene bridged hybrid

- CC1/2

correlation coefficient ½

- DHAP

1,3-dihydroxy-acetonephosphate

- hACMSD

human ACMSD

- 3-HAA

3-hydroxyanthranilic acid

- HAO

3-hydroxyanthranilic acid dioxygenase

- H-bond

hydrogen bond

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- HTVS

high throughput virtual screening

- MMGBSA

molecular mechanics-generalized Born surface area

- PA

picolinic acid

- PAINS

pan-assay interference compounds

- PDB

protein data bank

- PDC

pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid

- pfACMSD

pseudomonas fluorescens ACMSD

- QUIN

quinolinic acid

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

- SP

standard precision

- XP

extra precision

Footnotes

Structures of compounds screened; Preliminary inhibition data for compounds 11, 16–23, and 26–27; Docking scores for the top 50 compounds from the virtual screen; Sequence alignment for human and P. fluorescens ACMSD; HPLC and 1H NMR data for all diflunisal analogs tested; certifications of purity for commercially acquired compounds.

Accession Codes

The structural coordinates for the X-ray structure of ACMSD in complex with diflunisal (1; PDB code 7K12) and 11 (PDB code 7K13) have been deposited to the RCSB Protein Data Base (www.rcsb.org). Authors will release the atomic coordinates upon article publication.

References

- 1.Wang Y; Liu KF; Yang Y; Davis I; Liu A Observing 3-hydroxyanthranilate-3,4-dioxygenase in action through a crystalline lens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2020, 117, 19720–19730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palzer L; Bader JJ; Angel F; Witzel M; Blaser S; McNeil A; Wandersee MK; Leu NA; Lengner CJ; Cho CE; Welch KD; Kirkland JB; Meyer RG; Meyer-Ficca ML Alpha-amino-beta-carboxy-muconate-semialdehyde decarboxylase controls dietary niacin requirements for NAD(+) synthesis. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1359–1370.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katsyuba E; Mottis A; Zietak M; De Franco F; van der Velpen V; Gariani K; Ryu D; Cialabrini L; Matilainen O; Liscio P; Giacche N; Stokar-Regenscheit N; Legouis D; de Seigneux S; Ivanisevic J; Raffaelli N; Schoonjans K; Pellicciari R; Auwerx J De novo NAD+ synthesis enhances mitochondrial function and improves health. Nature 2018, 563, 354–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarcz R; Whetsell WO Jr.; Mangano RM Quinolinic acid: an endogenous metabolite that produces axon-sparing lesions in rat brain. Science 1983, 219, 316–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beal MF; Kowall NW; Ellison DW; Mazurek MF; Swartz KJ; Martin JB Replication of the neurochemical characteristics of Huntington’s disease by quinolinic acid. Nature 1986, 321, 168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone TW; Darlington LG Endogenous kynurenines as targets for drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2002, 1, 609–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarcz R The kynurenine pathway of tryptophan degradation as a drug target. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 2004, 4, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarcz R; Bruno JP; Muchowski PJ; Wu HQ Kynurenines in the mammalian brain: when physiology meets pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 2012, 13, 465–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muraki T; Taki M; Hasegawa Y; Iwaki H; Lau PCK Prokaryotic homologs of the eukaryotic 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase and 2-amino-3-carboxymuconate-6-semialdehyde decarboxylase in the 2-nitrobenzoate degradation pathway of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain KU-7. App. Environm. Microbiol 2003, 69, 1564–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li T; Iwaki H; Fu R; Hasegawa Y; Zhang H; Liu A α-Amino-β-carboxymuconic-ε-semialdehyde decarboxylase (ACMSD) is a new member of the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 6628–6634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martynowski D; Eyobo Y; Li T; Yang K; Liu A; Zhang H Crystal structure of α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde decarboxylase: Insight into the active site and catalytic mechanism of a novel decarboxylation reaction. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 10412–10421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li T; Walker AL; Iwaki H; Hasegawa Y; Liu A Kinetic and spectroscopic characterization of ACMSD from Pseudomonas fluorescens reveals a pentacoordinate mononuclear metallocofactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 12282–12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huo L; Fielding AJ; Chen Y; Li T; Iwaki H; Hosler JP; Chen L; Hasegawa Y; Que L; Liu A Evidence for a dual role of an active site histidine in α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde Decarboxylase. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 5811–5821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huo L; Liu F; Iwaki H; Li T; Hasegawa Y; Liu A Human α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde decarboxylase (ACMSD): A structural and mechanistic unveiling. Proteins 2015, 83, 178–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huo L; Davis I; Chen L; Liu A The power of two: arginine 51 and arginine 239* from a neighboring subunit are essential for catalysis in alpha-amino-beta-carboxymuconate-epsilon-semialdehyde decarboxylase. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 30862–30871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y; Davis I; Matsui T; Rubalcava I; Liu A Quaternary structure of α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ϵ-semialdehyde decarboxylase (ACMSD) controls its activity. J. Biol. Chem 2019, 294, 11609–11621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garavaglia S; Perozzi S; Galeazzi L; Raffaelli N; Rizzi M The crystal structure of human a-amino-b-carboxymuconic-e-semialdehyde decarboxylase in complex with 1,3-dihydroxyacetonephosphate suggests a regulatory link between NAD synthesis and glycolysis. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 6615–6623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuwatari T; Ohsaki S; Fukuoka S.-i.; Sasaki R; Shibata K Phthalate esters enhance quinolinate production by inhibiting α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde decarboxylase (ACMSD), a key enzyme of the tryptophan pathway. Toxicol. Sci 2004, 81, 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellicciari R; Liscio P; Giacchè N; De Franco F; Carotti A; Robertson J; Cialabrini L; Katsyuba E; Raffaelli N; Auwerx J α-Amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde decarboxylase (ACMSD) inhibitors as novel modulators of de novo nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) biosynthesis. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 745–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friesner RA; Banks JL; Murphy RB; Halgren TA; Klicic JJ; Mainz DT; Repasky MP; Knoll EH; Shelley M; Perry JK; Shaw DE; Francis P; Shenkin PS Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friesner RA; Murphy RB; Repasky MP; Frye LL; Greenwood JR; Halgren TA; Sanschagrin PC; Mainz DT Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halgren TA; Murphy RB; Friesner RA; Beard HS; Frye LL; Pollard WT; Banks JL Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2. Enrichment factors in database screening. J. Med. Chem 2004, 47, 1750–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrödinger Release 2017–3: Protein Preparation Wizard; Epik; Impact; Glide; Prime, Schrödinger LLC: New York, NY: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobson MP; Friesner RA; Xiang Z; Honig B On the role of the crystal environment in determining protein side-chain conformations. J. Mol. Biol 2002, 320, 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobson MP; Pincus DL; Rapp CS; Day TJF; Honig B; Shaw DE; Friesner RA A hierarchical approach to all-atom protein loop prediction. Proteins 2004, 55, 351–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu X; Xie W; Reed D; Bradshaw WS; Simmons DL Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs cause apoptosis and induce cyclooxygenases in chicken embryo fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1995, 92, 7961–7965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coşkun GP; Djikic T; Hayal TB; Türkel N; Yelekçi K; Şahin F; Küçükgüzel Ş G Synthesis, molecular docking and anticancer activity of diflunisal derivatives as cyclooxygenase enzyme inhibitors. Molecules 2018, 23, 1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li T; Ma J; Hosler JP; Davidson VL; Liu A Detection of transient intermediates in the metal-dependent non-oxidative decarboxylation catalyzed by a-amino-b-carboxymuconate-e-semialdehyde decarboxylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 9278–9279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu S; Lv M; Xiao D; Li X; Zhou X; Guo M A highly efficient catalyst of a nitrogen-based ligand for the Suzuki coupling reaction at room temperature under air in neat water. Org. Biomol. Chem 2014, 12, 4511–4516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karplus PA; Diederichs K Linking crystallographic model and data quality. Science 2012, 336, 1030–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engh RA; Huber R Accurate bond and angle parameters for X-ray protein structure refinement. Acta Crystallogr. Section A 1991, 47, 392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen VB; Arendall WB III; Headd JJ; Keedy DA; Immormino RM; Kapral GJ; Murray LW; Richardson JS; Richardson DC MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Section D. Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petros AM; Swann SL; Song D; Swinger K; Park C; Zhang H; Wendt MD; Kunzer AR; Souers AJ; Sun C Fragment-based discovery of potent inhibitors of the anti-apoptotic MCL-1 protein. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett 2014, 24, 1484–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y; Liu F; Liu A Adapting to oxygen: 3-Hydroxyanthrinilate 3, 4-dioxygenase employs loop dynamics to accommodate two substrates with disparate polarities. J. Biol. Chem 2018, 293, 10415–10424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duff MR Jr.; Gabel SA; Pedersen LC; DeRose EF; Krahn JM; Howell EE; London RE The structural basis for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug inhibition of human dihydrofolate Reductase. J. Med. Chem 2020, 63, 8314–8324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu HY; Wang PF; Li Z; Ma JT; Wang XM; Yang YH; Zhu HL Synthesis of dihydropyrazole sulphonamide derivatives that act as anti-cancer agents through COX-2 inhibition. Pharmacol. Res 2016, 104, 86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Küçükgüzel SG; Küçükgüzel I; Tatar E; Rollas S; Sahin F; Güllüce M; De Clercq E; Kabasakal L Synthesis of some novel heterocyclic compounds derived from diflunisal hydrazide as potential anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2007, 42, 893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gales L; Macedo-Ribeiro S; Arsequell G; Valencia G; Saraiva MJ; Damas AM Human transthyretin in complex with iododiflunisal: structural features associated with a potent amyloid inhibitor. Biochem. J 2005, 388, 615–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wishart DS; Feunang YD; Guo AC; Lo EJ; Marcu A; Grant JR; Sajed T; Johnson D; Li C; Sayeeda Z; Assempour N; Iynkkaran I; Liu Y; Maciejewski A; Gale N; Wilson A; Chin L; Cummings R; Le D; Pon A; Knox C; Wilson M DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1074–D1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]