Abstract

An increased use of disinfectants during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may increase the number of adverse health effects among people who apply them or among those who are in the area being disinfected. For the 3-month period from January 1 to March 30, 2020, the number of calls about exposure to cleaners and disinfectants made to US poison centers in all states increased 20.4%, and the number of calls about exposure to disinfectants increased 16.4%. We examined calls about cleaners and disinfectants to the Michigan Poison Center (MiPC) since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. We compared all calls related to exposure to cleaners or disinfectants, calls with symptoms, and calls in which a health care provider was seen during the first quarters of 2019 and 2020 and in relationship to key COVID-19 dates. From 2019 to 2020, the number of all disinfectant calls increased by 42.8%, the number of calls with symptoms increased by 57.3%, the average number of calls per day doubled after the first Michigan COVID-19 case, from 4.8 to 9.0, and the proportion of calls about disinfectants among all exposure calls to the MiPC increased from 3.5% to 5.0% (P < .001). Calls for exposure to cleaners did not increase significantly. Exposure occurred at home for 94.8%97.1% of calls, and ingestion was the exposure route for 59.7% of calls. Information about the adverse health effects of disinfectants and ways to minimize exposure should be included in COVID-19 pandemic educational materials.

Keywords: COVID-19, cleaning agents, disinfectants, poison center calls

Part of the response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been the recommendation that “frequent disinfection of surfaces and objects touched by multiple people is important.”1 An increased use of disinfectants may increase the number of adverse health effects among people who apply them or among those who are in the area being disinfected. For the 3-month period from January 1 to March 30, 2020, the number of calls about exposure to cleaners and disinfectants made to US poison centers increased 20.4%, and the number of calls about exposure to disinfectants increased 16.4%.2

Studies on the adverse health effects resulting from exposure to disinfectants and cleaning products, including asthma, allergic rhinitis, and other respiratory symptoms, predate the recommended increased use of disinfectants during the COVID-19 pandemic. The literature includes cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, case reports, and exposure analyses3-7; studies on respiratory allergens identified in cleaning products8-10; and studies identifying an increased risk of developing asthma with both the frequency of use and the method of application (eg, spraying vs wiping) of cleaning agents.11

We report data on calls made about exposures to cleaners and disinfectants to the Michigan Poison Center (MiPC). Data available at the state level allowed us to expand on national data. We also examined subcategories in the call data, including calls involving symptoms and calls in which the caller saw a health care provider.

Methods

We examined data on calls to the MiPC located at Wayne State University School of Medicine, which covers the entire state of Michigan. We accessed data from the MiPC ToxSentry system from January 1 to April 30, 2019, and from January 1 to April 30, 2020. Using the ToxSentry Query Builder, we selected data on all calls for exposure to cleaners or disinfectants. For each call, we extracted data on the call date, exposure type, exposure location, routes of exposure, age, sex, symptoms, and whether the caller sought medical care with a health care provider. If calls indicated multiple routes of exposure, we used the first route listed in the analyses.

Because bleach is regulated by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as a disinfectant,12 in our analyses we grouped bleach with other disinfectants rather than with cleaners.

We used negative binomial regression to predict the number of calls around 4 dates: January 19, 2020 (the date on which the first case of COVID-19 was reported in the United States in Washington State); March 10, 2020 (the date the first case of COVID-19 was reported in Michigan); March 22, 2020 (the date the governor of Michigan issued the first executive order on social distancing); and April 23, 2020 (the date of President Trump’s statement about ingesting/injecting disinfectants). We used the Supremum Wald χ2 test to determine whether and when a structural break occurred in the number of daily calls.13,14 We used the χ2 trend test to compare exposure routes during 2019 and 2020.15 We conducted all analyses using Stata version 14 (StataCorp).

Results

From January 1–April 30, 2019, to January 1–April 30, 2020, the number of calls to the MiPC about cleaners increased by 4.5% (from 897 to 937) and the number of calls about disinfectants increased by 42.8% (from 608 to 868; Table). We found a nonsignificant increase in the proportion of calls about cleaners among all calls received, from 5.1% during January 1–April 30, 2019 (n = 17 550) to 5.4% during January 1–April 30, 2020 (n = 17 247; P = .18), but a significant increase in the proportion of calls about disinfectants among all calls, from 3.5% to 5.0% (P < .001).

Table.

Calls to the Michigan Poison Control Center about exposure to cleaners or disinfectants, January 1–April 30, 2019, and January 1–April 30, 2020a

| Variable | Total | Cleaners | Disinfectants | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calls for cleaners and disinfectants | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | ||||||||||

| 2019 | 2020 | All calls | Calls with ≥1 symptom | Saw health care provider | All calls | Calls with ≥1 symptom | Saw health care provider | All calls | Calls with ≥1 symptom | Saw health care provider | All calls | Calls with ≥1 symptom | Saw health care provider | |

| Total no. | 1505 | 1805 | 897 | 302 | 159 | 937 | 342 | 107 | 608 | 234 | 120 | 868 | 368 | 93 |

| Age group, yb | ||||||||||||||

| 0-5 | 851 (60.2) | 852 (48.2) | 585 (68.3) | 155 (53.4) | 67 (43.2) | 552 (59.9) | 142 (42.3) | 39 (36.4) | 266 (47.8) | 54 (24.9) | 27 (22.9) | 300 (35.5) | 69 (19.2) | 17 (18.3) |

| 6-15 | 79 (5.6) | 84 (4.8) | 42 (4.9) | 17 (5.9) | 8 (5.2) | 41 (4.5) | 16 (4.8) | 4 (3.7) | 37 (6.7) | 22 (10.1) | 18 (15.3) | 43 (5.1) | 23 (6.4) | 9 (9.7) |

| ≥16 | 483 (34.2) | 831 (47.0) | 230 (26.8) | 118 (40.7) | 80 (51.6) | 328 (35.6) | 178 (53.0) | 64 (59.8) | 253 (45.5) | 141 (65.0) | 73 (61.9) | 503 (59.5) | 268 (74.4) | 67 (72.0) |

| Exposure routec | ||||||||||||||

| Ingestion | 1090 (72.6) | 1064 (59.7) | 707 (79.1) | 196 (65.3) | 105 (66.9) | 642 (69.3) | 170 (50.0) | 58 (54.7) | 383 (63.0) | 100 (42.7) | 79 (65.8) | 422 (49.4) | 121 (33.0) | 57 (61.3) |

| Inhalation | 116 (7.7) | 231 (13.0) | 34 (3.8) | 19 (6.3) | 10 (6.4) | 54 (5.8) | 33 (9.7) | 5 (4.7) | 82 (13.5) | 48 (20.5) | 11 (9.2) | 177 (20.7) | 103 (28.1) | 10 (10.8) |

| Dermal | 169 (11.3) | 340 (19.1) | 93 (10.4) | 41 (13.7) | 24 (15.3) | 160 (17.3) | 73 (21.5) | 19 (17.9) | 76 (12.5) | 30 (12.8) | 13 (10.8) | 180 (21.1) | 81 (22.1) | 13 (14.0) |

| Ocular | 127 (8.5) | 147 (8.2) | 60 (6.7) | 44 (14.7) | 18 (11.5) | 71 (7.7) | 64 (18.8) | 24 (22.6) | 67 (11.0) | 56 (23.9) | 17 (14.2) | 76 (8.9) | 62 (16.9) | 13 (14.0) |

| Exposure locationd | ||||||||||||||

| Workplace | 55 (3.8) | 69 (4.0) | 30 (3.4) | 21 (7.1) | 20 (13.0) | 26 (2.9) | 19 (5.8) | 10 (10.1) | 25 (4.3) | 21 (9.3) | 13 (11.6) | 44 (5.2) | 36 (10.0) | 15 (17.4) |

| Home | 1411 (96.2) | 1676 (96.0) | 850 (96.6) | 274 (92.9) | 134 (87.0) | 878 (97.1) | 308 (94.2) | 89 (89.9) | 561 (95.7) | 206 (90.7) | 99 (88.4) | 797 (94.8) | 323 (90.0) | 71 (82.6) |

aAll data are no. (%) unless otherwise specified.

bData on age were unknown for 92 calls in 2019 and 38 calls in 2020.

cData on exposure route were other or unknown for 3 calls in 2019 and 23 calls in 2020.

dData on exposure location were other or unknown for 39 calls in 2019 and 60 calls in 2020.

The number of calls about cleaners in which the caller had ≥1 symptom increased by 13.2% (from 302 to 342) from January 1–April 30, 2019, to January 1–April 30, 2020, but the number of calls about cleaners in which the caller saw a health care provider decreased by 32.7% (from 159 to 107; Table). For disinfectants, the number of calls in which the caller had ≥1 symptom increased by 57.3% (from 234 to 368), but the number of calls in which the caller saw a health care provider decreased by 22.5% (from 120 to 93).

Most calls to the MiPC about cleaners or disinfectants were related to exposure at home (range, 94.8%-97.1%). Ingestion was the most common exposure route in all age groups: 73.8% among children aged ≤5 years, 64.6% among children and adolescents aged 6-15 years, and 45.8% among people aged ≥16 years (P < .001). From 2019 to 2020 in all age groups combined, calls for ingestion as the exposure route decreased from 72.6% to 59.7% (P < .001), calls increased for inhalation (from 7.7% to 13.0%; P < .001) and dermal exposures (from 11.3% to 19.1%; P < .001), and calls for ocular exposures were unchanged (from 8.5% to 8.2%; P = .76; Table). These changes in exposure routes occurred among children and adolescents aged 6-15 years and people aged ≥16 years. Among children aged ≤5 years, calls for ingestion as the exposure route increased from 73.6% to 84.6% (P < .001).

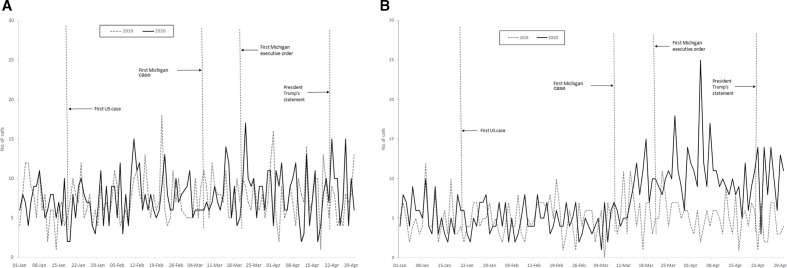

The number of daily calls doubled for disinfectants on March 13, 2 days after the first COVID-19 case in Michigan, from 4.8 (95% CI, 4.2-5.4) per day to 9.0 (95% CI, 7.2-10.8) per day (Figure A and B). The number of daily calls did not increase significantly for cleaners, from 8.0 (95% CI, 6.2-9.8) per day to 7.6 (95% CI, 6.8-8.4) per day. The number of calls for exposure to cleaners or disinfectants related to January 19, March 22, or April 23 did not increase significantly. We found a significant structural break of an increase in daily calls for exposure to disinfectants on March 13, two days after the first COVID-19 case was reported in Michigan (P < .001). We found no significant structural break of an increase in daily calls for exposure to cleaners (P = .65).

Figure.

Number of calls per day to the Michigan Poison Center from January 1 to April 30, 2019, and January 1 to April 30, 2020, for exposure to cleaners (A) and disinfectants (B). Cases refer to cases of coronavirus disease 2019.

Discussion

From the first 4 months of 2019 to the first 4 months of 2020, the overall number of calls about disinfectants and the number of calls with symptoms from disinfectants increased by about 50%. This increase in calls about disinfectants is consistent with public health guidance recommending more use of disinfectants and the known hazards of disinfectants. This increase equaled to a doubling in the number of calls per day about exposures to disinfectants from approximately 5 to 10 that began 2 days after the first reports of COVID-19 cases in Michigan on March 11, 2020. The use of disinfectants in Michigan appeared to have increased when the public viewed COVID-19 as a local public health hazard; the number of calls in Michigan did not increase in relation to the first reported COVID-19 case in the state of Washington. Also, there was no further change after Michigan’s stay-at-home order or in response to misinformation reported by the president.

In contrast with the calls about disinfectants, calls about exposure to cleaners did not increase significantly. National data from January to March 30, 2020, showed a larger increase in calls related to exposure to cleaners than to exposure to disinfectants (20.4% vs 16.2%).2 This difference in national data compared with data in Michigan is likely because the national analysis included bleach as a cleaner, whereas in Michigan, we included bleach as a disinfectant, as bleach is approved and recommended as a disinfectant for COVID-19.12 Bleach accounted for 62.1% of the increase in cleaner-related calls in the national data reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2

Despite the increase in exposure calls for disinfectants in which the caller had ≥1 symptom, we found a decrease in the number of visits to a health care provider, which likely reflects the general decrease in non–COVID-19 health care visits during this time.16

The increase in calls and symptoms underscores the importance of proper use of disinfectants and avoiding overuse of these chemicals to maximize their benefits and minimize their adverse effects. Improper mixing of bleach products with either an acid or an ammonia product can generate chlorine or chloramine fumes that can cause chemical pneumonitis and/or pulmonary edema. Not following the direction on dilution and overconcentrating or preparing the compounds for use in a poorly ventilated utility closet or bathroom increases exposure. Although ingestion as the route of exposure decreased in 2020 compared with 2019 among people aged 6-15 years and ≥16 years, it increased among children aged ≤5 years and remained the major exposure route for both adults and children. CDC reported the same results in national data.2 With more disinfecting being performed, a greater number of cleaning product containers will presumably be present in homes and workplaces. Containers need to be properly labeled so they are not mistakenly ingested and not left or stored where young children can access them. Use of gloves and eye protection and application with a rag rather than by spraying are all important ways to reduce potential dermal, ocular, and respiratory exposure.

Concern about the adverse effects of disinfectants preceded the COVID-19 pandemic,3-11 and brochures and guidelines for the use of bleach and other disinfectants, cleaning in general, and cleaning in schools and childcare centers have been developed and can provide guidance for COVID-19 educational material. As an example, cleaning products certified by EcoLogo or Green Seal prohibit asthma-causing agents.17,18 It is also important to ensure that the disinfectant selected is effective against COVID-19. The EPA has a list of products that meet the criteria for effectiveness against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).12 The EPA-approved list includes compounds that are known and not known to cause asthma or allergic rhinitis.19 Because the compounds not known to cause an allergic reaction are still irritants, these compounds might exacerbate symptoms in people who already had asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or rhinitis. Potential irritants on the EPA-approved list are citric acid, ethanol, glycolic acid, isopropanol, lactic acid, phenolic, hydrogen peroxide, and hypochlorous acid. Substances on the EPA-approved list that are both irritants and respiratory allergens are bleach (sodium hypochlorite) and quaternary ammonium compounds.

Limitation

The poison center data had 1 limitation. Data for 2019 and 2020 were self-reported and were not validated with a review of medical records, measurement of levels of exposure, or collection of the actual products used.

Conclusion

The increase in calls to the poison center about exposures to disinfectants in the first few months of their presumed increased use during the COVID-19 pandemic speaks to the inclusion of information about the proper use, protections, and potential adverse health effects of disinfectants in the educational material about the use of disinfectants in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As more schools and businesses open during the pandemic, the inclusion of this guidance is more critical than ever to protect children, teachers, staff members, and other employees who will likely have increased exposure to these chemicals.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by cooperative agreement U60-OH008466 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

ORCID iD

Kenneth D. Rosenman, MD https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2053-4849

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Reopening guidance for cleaning and disinfecting public spaces, workplaces, businesses, schools, and homes. Updated May 7, 2020. Accessed May 11, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/reopen-guidance.html

- 2.Chang A., Schnall AH., Law Ret al. Cleaning and disinfectant chemical exposures and temporal associations with COVID-19—National Poison Data System, United States, January 1, 2020–March 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(16):496-498. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6916e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folletti I., Zock J-P., Moscato G., Siracusa A. Asthma and rhinitis in cleaning workers: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. J Asthma. 2014;51(1):18-28. 10.3109/02770903.2013.833217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siracusa A., De Blay F., Folletti Iet al. Asthma and exposure to cleaning products—a European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology task force consensus statement. Allergy. 2013;68(12):1532-1545. 10.1111/all.12279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore VC., Burge PS., Robertson AS., Walters GI. What causes occupational asthma in cleaners? Thorax. 2017;72(6):581-583. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinmann T., Gerlich J., Heinrich Set al. Association of household cleaning agents and disinfectants with asthma in young German adults. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74(9):684-690. 10.1136/oemed-2016-104086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svanes Ø., Bertelsen RJ., Lygre SHLet al. Cleaning at home and at work in relation to lung function decline and airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(9):1157-1163. 10.1164/rccm.201706-1311OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee HS., Chan CC., Tan KT., Cheong TH., Chee CB., Wang YT. Burnisher’s asthma—a case due to ammonia from silverware polishing. Singapore Med J. 1993;34(6):565-566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purohit A., Kopferschmitt-Kubler MC., Moreau C., Popin E., Blaumeiser M., Pauli G. Quaternary ammonium compounds and occupational asthma. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2000;73(6):423-427. 10.1007/s004200000162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cristofari-Marquand E., Kacel M., Milhe F., Magnan A., Lehucher-Michel M-P. Asthma caused by peracetic acid-hydrogen peroxide mixture. J Occup Health. 2007;49(2):155-158. 10.1539/joh.49.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zock J-P., Plana E., Jarvis Det al. The use of household cleaning sprays and adult asthma: an international longitudinal study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(8):735-741. 10.1164/rccm.200612-1793OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Environmental Protection Agency Pesticide registration: list N: disinfectants for use against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Accessed May 11, 2020 https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2

- 13.Andrews DWK. Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point. Econometrica. 1993;61(4):821-856. 10.2307/2951764 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrews DWK. Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point: a corrigendum. Econometrica. 2003;71(1):395-397. 10.1111/1468-0262.00405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armitage P. Tests for linear trends in proportions and frequencies. Biometrics. 1955;11(3):375-386. 10.2307/3001775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartnett KP., Kite-Powell A., DeVies Jet al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(23):699-704. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UL ECOLOGO certification program. Accessed July 20, 2020 https://www.ul.com/resources/ecologo-certification-program

- 18.Green Seal https://greenseal.org Accessed July 20, 2020.

- 19.Rosenman KD., Beckett WS. Web based listing of agents associated with new onset work-related asthma. Respir Med. 2015;109(5):625-631. 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]