Abstract

Background

Pulmonary vascular disease is associated with poor outcomes in individuals affected by interstitial lung disease. The pulmonary vessels can be quantified with noninvasive imaging, but whether radiographic indicators of vasculopathy are associated with early interstitial changes is not known.

Research Question

Are pulmonary vascular volumes, quantified from CT scans, associated with interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA) in a community-based sample with a low burden of lung disease?

Study Design and Methods

In 2,386 participants of the Framingham Heart Study, we used CT imaging to calculate pulmonary vascular volumes, including the small vessel fraction (a surrogate of vascular pruning). We constructed multivariable logistic regression models to investigate associations of vascular volumes with ILA, progression of ILA, and restrictive pattern on spirometry. In secondary analyses, we additionally adjusted for diffusing capacity and emphysema, and performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to participants with normal FVC and diffusing capacity.

Results

In adjusted models, we found that lower pulmonary vascular volumes on CT were associated with greater odds of ILA, antecedent ILA progression, and restrictive pattern on spirometry. For example, each SD lower small vessel fraction was associated with 1.81-fold greater odds of ILA (95% CI, 1.41-2.31; P < .0001), and 1.63-fold greater odds of restriction on spirometry (95% CI, 1.18-2.24; P = .003). Similar patterns were seen after adjustment for diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide, emphysema, and among participants with normal lung function.

Interpretation

In this cohort of community-dwelling adults not selected on the basis of lung disease, more severe vascular pruning on CT was associated with greater odds of ILA, ILA progression, and restrictive pattern on spirometry. Pruning on CT may be an indicator of early pulmonary vasculopathy associated with interstitial lung disease.

Key Words: epidemiology (pulmonary), imaging, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary circulation

Abbreviations: BV5, blood vessel volume of pulmonary vessels with cross-sectional area <5 mm2; Dlco, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; ILA, interstitial lung abnormality; ILD, interstitial lung disease; TBV, total blood vessel volume of all pulmonary vessels

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 473

Pulmonary hypertension commonly occurs in the setting of interstitial lung disease (ILD), and it is a strong predictor of morbidity and mortality in individuals affected by ILD of different causes.1, 2, 3, 4 Although earlier detection of pulmonary vasculopathy associated with ILD may improve prognostication and alter the approach to treatment,5 invasive approaches such as right heart catheterization are not practical for detecting pulmonary hypertension in its early, clinically silent phase.6 Quantitative imaging tools may allow for noninvasive assessment of the pulmonary vasculature.7

Histologic evaluation of lungs with ILD have shown narrowing, occlusion, and loss of the small pulmonary vessels,8, 9, 10 a process that eventually results in “pruning” of the vascular tree. Analysis of CT imaging can quantify pulmonary blood vessel volume, and a relative reduction in the volume of the smaller vessels on CT has been described as radiographic pruning.11 CT pruning has been linked to microscopic small vessel loss on histology12 and also with poorer lung function, more severe pulmonary hypertension, and greater mortality in individuals with more severe airways disease, including COPD and asthma.11,13, 14, 15, 16 We recently found that CT pruning was associated with lower lung function and airflow obstruction among participants of the Framingham Heart Study,17 indicating that this may be a sensitive and clinically relevant marker of pulmonary vasculopathy in airways disease. However, whether CT-based vascular pruning is associated with ILD, particularly in healthier populations with early or pre-clinical interstitial disease, is unknown.

To address this knowledge gap, we investigated associations of CT pulmonary vascular volumes and interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA) in the Framingham Heart Study, a representative community-based sample not selected on the basis of ILD. Based on prior histologic evidence of pruning in ILD, we hypothesized that CT pruning would be associated with greater odds of ILA on imaging and restrictive pattern on spirometry, even in a population with a low overall burden of lung disease.

Methods

Study Population

The study population consists of participants of the Framingham Heart Study Offspring and Third Generation cohorts who underwent volumetric thoracic CT between 2008 and 2011 as part of the multi-detector CT 2 sub-study.17,18 Of 2,764 participants who underwent thoracic CT, 2,470 had adequate data for pulmonary vascular assessment. We excluded those missing demographic data or information on smoking history (n = 82). We also excluded participants who did not have either ILA assessment on CT or evaluation of spirometry. This resulted in an overall total of 2,386 participants who were included in either the ILA or spirometric analyses (n = 2,291 and n = 2,255, respectively). To investigate ILA progression, our analysis included a subgroup of 1,635 participants with assessment of ILA on a prior cardiac CT from the Multi-Detector CT 1 sub-study (2002-2005). This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (protocol 2009P000224) approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Radiographic Pulmonary Vascular Assessment

Inspiratory, noncontrast CT examinations covering the entire thorax were performed in the supine position using a 64-detector-row scanner (Discovery, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). Acquisition parameters were 120 kVp, 300 to 350 mA (based on body weight), 350 ms rotation time, and 0.625-mm section thickness, and uniform reconstruction protocols were used. Using software based on the Chest Imaging Platform (www.chestimagingplatform.org), vascular image analysis was performed in the Applied Chest Imaging Laboratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital as previously described.11 Three-dimensional reconstructions of the pulmonary vasculature were generated by automated algorithm, from which the volume of vessels of varying cross-sectional area were calculated (Fig 1), including the total volume of all intraparenchymal vessels (TBV) and of the small vessels (defined by cross-sectional area <5 mm2, BV5). These measures include both arterial and venous volumes. The small vessel fraction (BV5/TBV), indicating the relative distribution of blood vessel volume in the smallest, most peripheral blood vessels detectable by CT, was calculated to represent radiographic vascular pruning.11,13,17,18

Figure 1.

A, Axial CT sections from a Framingham Heart Study participant with normal pulmonary parenchyma (left) and interstitial lung abnormalities (right). B, Three-dimensional volumetric reconstructions of the pulmonary vascular tree, generated from the CTs in A, demonstrating relative loss of the smallest pulmonary vessels (ie, vascular pruning) in the participant with interstitial lung abnormality on CT. Vessels are color-coded by size.

Assessment of Interstitial Lung Abnormalities

Thoracic CTs were reviewed for interstitial lung abnormalities via a modified sequential reading method.19,20 ILA was defined as present if visual inspection showed nondependent changes (traction bronchiectasis, honeycombing, ground-glass/reticular abnormalities, diffuse centrilobular nodularity, or cysts) affecting mor than 5% of any lung zone. Only changes in nondependent lung regions were considered to differentiate from atelectasis. Patchy, focal, or unilateral abnormalities were considered to be “indeterminate,” because these findings are commonly observed and are likely to represent a more isolated insult (eg, pneumonia) rather than a diffuse interstitial process.21 ILA assessment was performed on the same thoracic CT scans used to generate the pulmonary vascular volumes, and was available for 2,291 (96.0%) participants. In addition, 1,635 participants within our sample also had a prior (round 1) cardiac CT, which provided a limited view of the lung parenchyma from roughly the level of the carina to the diaphragm.22 Paired images from the prior cardiac CT and the subsequent (whole-lung) thoracic CTs were compared to evaluate for change. Consistent with prior work, participants with ILA on initial cardiac CT who had probable/definite progression on subsequent thoracic CT were categorized as “ILA with progression,” whereas those with unchanged ILA or regression were categorized as “ILA without progression.” “No ILA” was absence of ILA on both CTs, and all remaining scans were categorized as “indeterminate.”22 This method of defining ILA has high agreement when compared with a consensus-based method23; it compares favorably to quantitative assessment based on densitometric thresholds,19 and it is linked to poorer outcomes, including mortality.24

Lung function testing was performed at the time of each study examination as previously described.17 Measures of pulmonary function included FEV1, FVC, and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (Dlco). Plethysmographic lung volume measurement was not performed, so we used a restrictive pattern on spirometry (ie, percent-predicted FVC < 80% and FEV1/FVC ratio ≥ 0.70) as a surrogate for restriction by lung volumes; this definition is sensitive, although less specific.25 Two thousand two hundred fifty-five (94.5%) participants had available spirometry data.

Statistical Methods

Multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine associations of CT vascular measures (TBV, BV5, and BV5/TBV) with a binary outcome (ie, restrictive pattern on spirometry). For analyses involving categorical outcome variables with multiple levels (eg, ILA present/absent/indeterminate), we used multinomial logistic regression models with “no ILA” chosen as the reference group. These models assume a multinomial probability distribution for the outcome, and thus they allow for a direct comparison of the odds of each outcome category relative to the reference group in the setting of multiple possible outcomes.26 All models included covariates selected a priori based on known or suspected associations with interstitial/restrictive lung disease, thoracic size, or abnormalities of pulmonary vessels. These included age (at time of thoracic CT), sex, height, weight, smoking status (current/former/never), total pack-years of cigarette use, personal educational attainment,27 occupation,28 median household income of neighborhood census tract,28 and study cohort. We did not adjust for race or ethnicity because nearly all participants were of European ancestry.29

In secondary analyses, we examined models additionally adjusted for Dlco to determine whether the association between CT-based measures of macrovascular structure and ILA was explained by differences in microvascular function as assessed by Dlco. We also performed additional adjustment for radiographic emphysema, to account for the known association of COPD and histologic pruning30 and the previously described impact of emphysema on lung volumes in ILA.31 To investigate the association of pulmonary vascular volumes on CT with ILA in those with very early interstitial changes, we performed sensitivity analyses restricted to participants with normal lung function (FVC and Dlco >80% predicted). Finally, given that smoking is known to be associated with both ILA22,32 and pulmonary vascular remodeling,30 we added interaction terms to our primary models to test for evidence of differential associations based on ever-smoking status.

ORs are reported with 95% CIs and expressed per SD difference in the vascular parameter. For interaction terms, a two-sided P < .10 for the Wald test was used as the threshold for statistically significant heterogeneity of the association. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Study Participant Characteristics

Details of the study cohort, with stratification by ILA status, are provided in Table 1. For the entire sample, half (51.1%) were female, half (49.0%) were never smokers, and the mean age was 59.0 ± 11.7 years. Average lung function in this cohort (percent-predicted FEV1, FVC, and Dlco) was normal. One hundred thirty participants (5.7%) had ILA on CT, whereas 907 (39.6%) were indeterminate. Among the 1,635 participants with a previous cardiac CT suitable for paired ILA assessment, over a mean interval of 6.1 ± 0.8 years, 85 participants (5.2%) had ILA with progression, 32 (2.0%) had ILA without progression, 904 (55.3%) were indeterminate, and the remainder had no ILA on either CT. Sixty-nine individuals (3.1%) had a restrictive pattern on spirometry.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants (N = 2,386), With Stratification by ILA Statusa

| Characteristic | Entire Sample (N = 2,386) | No ILA (n = 1,254) | ILA (n = 130) | Indeterminate (n = 907) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 59.0 ± 11.7 | 56.0 ± 10.6 | 69.6 ± 11.7 | 61.3 ± 11.7 |

| Female, No. (%) | 1,219 (51.1) | 626 (49.9) | 67 (51.5) | 474 (52.3) |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 28.4 ± 5.4 | 28.7 ± 5.6 | 28.5 ± 5.6 | 28.1 ± 5.1 |

| Occupation category, No. (%) | ||||

| Laborer | 191 (8.0) | 105 (8.4) | 13 (10) | 60 (6.6) |

| Sales/clerical | 609 (25.5) | 327 (26.1) | 24 (18.5) | 239 (26.4) |

| Professional/executive/supervisory/technical | 987 (41.4) | 577 (46) | 32 (24.6) | 348 (38.4) |

| Other | 599 (25.1) | 245 (19.5) | 61 (46.9) | 260 (28.7) |

| Educational attainment, No. (%) | ||||

| High school or less | 504 (21.1) | 231 (18.4) | 44 (33.9) | 200 (22.1) |

| Some college | 758 (31.8) | 399 (31.8) | 45 (34.6) | 283 (31.2) |

| College/grad school | 1,124 (47.1) | 624 (49.8) | 41 (31.5) | 424 (46.8) |

| Median household income, $, median (IQR) | 83,065 (36,801) | 82,597 (36,155) | 82,087 (39,750) | 83,532 (42,265) |

| Offspring cohort, No. (%) | 1,091 (45.7) | 460 (36.7) | 99 (76.2) | 463 (51.1) |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | ||||

| Never | 1,168 (49.0) | 646 (51.5) | 53 (40.8) | 421 (46.4) |

| Former | 1,042 (43.7) | 530 (42.3) | 59 (45.4) | 414 (45.6) |

| Current | 176 (7.4) | 78 (6.2) | 18 (13.9) | 72 (7.9) |

| Pack-years of smoking, mean ± SD | ||||

| Entire sample | 9.8 ± 15.7 | 8.3 ± 13.9 | 15.5 ± 18.8 | 11.1 ± 17.3 |

| Former smokers | 16.9 ± 16.7 | 15.4 ± 15.0 | 22.1 ± 17.9 | 18.2 ± 18.3 |

| Current smokers | 32.6 ± 15.3 | 28.8 ± 14.9 | 39.2 ± 9.2 | 34.7 ± 15.9 |

| Percent-predicted FEV1, mean ± SD | 97.9 ± 15.2 | 97.8 ± 14.7 | 96.9 ± 17.4 | 98.4 ± 15.2 |

| Percent-predicted FVC, mean ± SD | 101.8 ± 13.3 | 101.2 ± 13.0 | 100.6 ± 15.0 | 102.9 ± 13.4 |

| Percent-predicted Dlco, mean ± SD | 96.6 ± 15.7 | 98.1 ± 15.4 | 85.8 ± 15.1 | 96.4 ± 15.6 |

| Restrictive pattern on spirometry, FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FVC < 80%; No. (%) | 69 (3.1) | 40 (3.4) | 4 (3.4) | 20 (2.4) |

| CT pulmonary vascular volume measures | ||||

| TBV, mL, mean ± SD | 143.1 ± 30.8 | 146.7 ± 31.4 | 137.5 ± 32.6 | 138.8 ± 28.7 |

| BV5, mL, mean ± SD | 55.9 ± 11.5 | 57.7 ± 11.7 | 52.0 ± 12.3 | 53.8 ± 10.6 |

| BV5/TBV, %, mean ± SD | 39.3 ± 4.1 | 39.6 ± 3.9 | 38.1 ± 4.3 | 39.0 ± 4.1 |

BV5 = blood vessel volume of pulmonary vessels with cross-sectional area < 5 mm2; Dlco = diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; IQR = interquartile range; TBV = total blood vessel volume of all pulmonary vessels.

n = 2,291; 95 participants did not have ILA data.

Associations With ILA, ILA Progression, and Restrictive Pattern on Spirometry

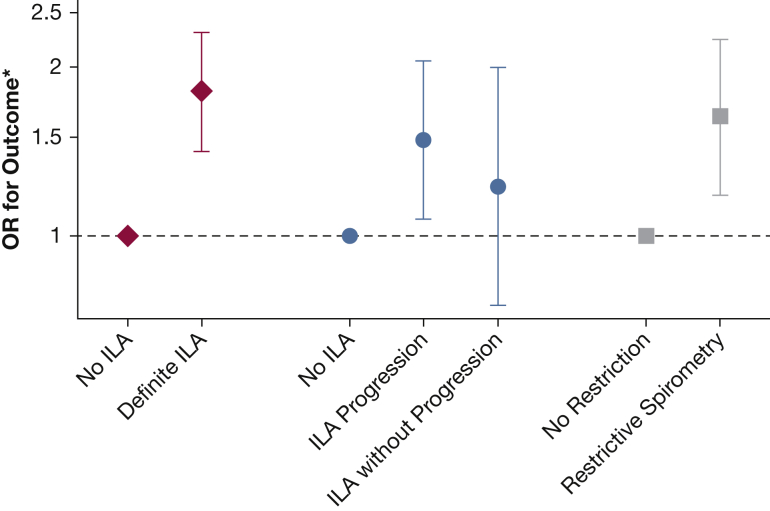

Associations of pulmonary blood vessel volumes with ILA, ILA progression, and restrictive pattern on spirometry are reported in Table 2. In adjusted models, we found that lower pulmonary vascular volumes were associated with greater odds of ILA on CT and restrictive pattern on spirometry. For example, each SD lower BV5/TBV (ie, more severe pruning) was associated with 1.81-fold greater odds of ILA (95% CI, 1.41-2.31; P < .0001), and 1.63-fold greater odds of restriction on spirometry (95% CI, 1.18-2.24; P = .003) (Fig 2). Similarly, lower vascular volumes on thoracic CT were associated with greater odds of ILA progression, but not with stable/improving ILA (Table 2, Fig 2). Results of associations with indeterminate ILA status are presented in e-Table 1 and e-Fig 1.

Table 2.

Associations of Pulmonary Vascular Volumes on CT and Odds of ILA, ILA Progression, and Restrictive Pattern on Spirometry (Expressed per SD Lower Vascular Parameter)

| ILA on CT (n = 2,291) | ||

|---|---|---|

| CT Vascular Volume Parameter | ILA vs No ILA |

|

| OR (95% CI)a | P | |

| TBV (per –SD) | 1.52 (1.12, 2.05) | .007 |

| BV5 (per –SD) | 1.77 (1.37, 2.30) | <.0001 |

| BV5/TBV (per –SD) | 1.81 (1.41, 2.31) | <.0001 |

| ILA Progression (n = 1,635) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT Vascular Volume Parameter | ILA With Progression vs No ILA |

ILA Without Progression vs No ILA |

||

| OR (95% CI)a | P | OR (95% CI)a | P | |

| TBV (per –SD) | 1.62 (1.09, 2.40) | .02 | 1.11 (0.64, 1.94) | .71 |

| BV5 (per –SD) | 1.70 (1.23, 2.34) | .001 | 1.22 (0.77, 1.92) | .39 |

| BV5/TBV (per –SD) | 1.48 (1.07, 2.05) | .02 | 1.22 (0.75, 1.99) | .42 |

| Restrictive Pattern on Spirometry (n = 2,255) | ||

|---|---|---|

| CT Vascular Volume Parameter | Restrictive Pattern vs Nonrestrictive Pattern |

|

| OR (95% CI)a | P | |

| TBV (per –SD) | 4.48 (2.91, 6.89) | <.0001 |

| BV5 (per –SD) | 3.44 (2.41, 4.89) | <.0001 |

| BV5/TBV (per –SD) | 1.63 (1.18, 2.24) | .003 |

ILA = interstitial lung abnormality. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Results expressed per –SD (SD lower) CT vascular volume parameter. Results of multivariable logistic and multinomial regression models with adjustment for age, sex, height, weight, smoking status, total pack-years of cigarette exposure, personal educational attainment, occupation category, median household income, and Framingham Heart Study cohort (offspring vs third generation).

Figure 2.

Associations of vascular pruning on CT (BV5/TBV) with odds of ILA, ILA progression, and restrictive pattern on spirometry (expressed per SD lower BV5/TBV). ∗Results expressed per –SD (SD lower) CT vascular volume parameter. Results of multivariable logistic and multinomial logistic regression models with adjustment for age, sex, height, weight, smoking status, total pack-years of cigarette exposure, personal educational attainment, occupation category, median household income, and Framingham. Heart Study cohort (offspring vs third generation). BV5 = blood vessel volume of pulmonary vessels with cross-sectional area < 5 mm2; ILA = interstitial lung abnormality; TBV = total blood vessel volume of all pulmonary vessels.

Secondary Analyses

In secondary analyses, we constructed models additionally adjusted for Dlco. Lower Dlco was independently associated with greater odds of ILA; for example, in models including BV5/TBV, each SD lower Dlco was associated with 2.99-fold greater odds of ILA (95% CI, 1.99-4.48; P < .0001), with similar patterns for TBV and BV5. However, adjustment for Dlco did not substantially alter the association of pulmonary vascular volumes (TBV, BV5, BV5/TBV) with ILA or with ILA progression. Similarly, we found no differences in the primary pattern of associations when additionally adjusting for radiographic emphysema, or in sensitivity analyses restricted to the 1,759 participants with normal FVC and Dlco.

We found that the associations of CT pruning (BV5/TBV) with odds of ILA, ILA progression, and restrictive pattern on spirometry were not different based on ever-smoking status (all Pinteraction > .10). However, for TBV and BV5, we found that the associations with ILA and ILA progression were stronger among never smokers compared with ever smokers. For example, per SD lower TBV, never smokers had 1.72-fold greater odds of ILA (95% CI, 1.16-2.56; P = .007), whereas in ever smokers the association did not achieve statistical significance (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.92-1.77; P = .15) (Pinteraction = .03).

Discussion

In this large cohort of community-dwelling adults not selected on the basis of ILD, we found that more severe vascular pruning on CT was consistently associated with greater odds of ILA, ILA progression, and restrictive pattern on spirometry. The associations with ILA and ILA progression were robust to additional adjustment for Dlco and emphysema, and when restricting the analyses to participants with normal lung function. Our findings indicate that radiographic pulmonary vascular pruning may be an indicator of vasculopathy associated with interstitial abnormalities, even in a population with a low prevalence of clinically recognized lung disease.

Pulmonary vascular pruning assessed by quantitative CT analysis has been used as a surrogate of the angiographic vascular pruning33, 34, 35 and histologic vascular narrowing and obliteration that is known to occur in smokers with COPD.30,36 Vascular pruning on CT has been linked to more severe airways disease in prior studies, including cohorts enriched for disease (such as COPDGene11,14,15 and the Severe Asthma Research Program13), and also in a community-based population (the Framingham Heart Study17).

In contrast, much of the literature regarding quantitative vascular analysis in ILD has focused on the total pulmonary vascular volume on CT (usually expressed as a percentage of radiographic lung volume), which has also been termed “vessel-related structures” to reflect the adjoining regions of fibrosis included by the algorithm in the calculated volume. In a landmark series of studies encompassing a spectrum of ILD (including IPF, ILD associated with connective tissue disease, unclassifiable ILD, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis), Jacob et al37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 found that higher pulmonary vascular volumes predicted worse outcomes, including greater extent of ILD and higher mortality, and contributed prognostic information beyond existing models of disease severity. Several of these studies examined subdivisions of the pulmonary vascular volume based on vessel size, and associations of higher small vessel volume (<5 or 5-10 mm2) with poor outcome were similar to the associations involving total pulmonary vascular volume. These findings suggest that higher vascular volumes (whether in the small or large vessels), and not differences in the proportion of peripheral vasculature, were associated with worse prognosis among those with ILD.

However, histologic studies of ILD lungs have found similar structural vascular changes to those found in COPD, including proliferation and fibrosis of the intima and media, reduced vascular density, and obliteration of the small pulmonary vessels.2,8, 9, 10,30,36 Although the histologic correlates of ILAs per se are not as well studied as cohorts of definite ILD, prior work has shown that ILAs on CT were associated with typical histologic features of pulmonary fibrosis,43 which suggests that loss of small vessels also may be a feature of ILA-related vasculopathy. This existing literature evaluating histologic features of ILD is consistent with our finding that relative reductions in the smallest vessel volume on CT are closely linked to ILA and antecedent ILA progression. This contrasts with the work by Jacob et al,40 which demonstrated that, when separately analyzing vessels of different sizes, an increase in the absolute (non-indexed) volume of the smallest pulmonary vessels was associated with loss of lung function in IPF. This discrepancy may be attributable to the substantially different populations in these studies. For example, in a cohort of 283 IPF patients,37 the mean percent-predicted FVC and Dlco were 68.8% ± 20.5% and 36.1% ± 12.9%, respectively, compared with 100.6% ± 15.0% and 85.8% ± 15.1% in the participants with ILA in our study. Possibly structural changes indicated by CT pruning are more clearly evident in early disease, whereas in advanced fibrotic disease other mechanisms may dominate, including regional changes in vascular capacitance and blood flow due to noncompliant, fibrotic areas of lung, and possible misclassification of perivascular fibrosis as part of the vascular volume.37,41 Our findings also match more closely with prior work by Kanski et al,44 in which total pulmonary blood volume on MRI (also indexed to lung volume) was lower in individuals with systemic sclerosis compared with healthy control subjects.44 Further work is needed to examine imaging metrics of pulmonary vasculopathy across the spectrum of ILD severity, including people with asymptomatic ILA, which has important implications for the identification of individuals who may be at high risk for ILA development and early disease progression.

Our findings suggest that CT pruning may be a sensitive indicator of early pulmonary vasculopathy that occurs in association with interstitial abnormalities. The associations of CT pruning with ILA and ILA progression were robust to additional adjustment for Dlco, which is considered to be a sensitive measure of pulmonary vascular damage and perhaps the best indicator of disease severity in ILD,2,37,45,46 and for emphysema, which is known to be associated with CT pruning.11 Furthermore, our results were unchanged when restricting the analysis to participants with normal FVC and Dlco, suggesting that vascular pruning on CT may be detectable before traditional physiologic criteria for interstitial disease are met. Intriguingly, more severe CT pruning was associated with antecedent ILA progression from prior CT but not with ILA that did not progress. Although this finding suggests that CT pruning is linked to ILA progression, it is worth noting that only the latter time point was available for vascular analysis. Our study cannot determine the temporality of these associations, nor whether pruning is a risk factor for (rather than a consequence of) ILA progression. Finally, although tobacco is a risk factor for ILA, our findings indicate that CT pruning is detectable in ILA regardless of whether the interstitial changes are related to cigarette smoke exposure.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate associations of pulmonary vascular pruning on CT with measures of ILD in a cohort representative of the general community—one not selected on the basis of smoking or lung disease. Strengths of our study include the large cohort size, control for multiple demographic and behavioral potential confounders in all of our models, examination of both absolute and relative pulmonary vascular volumes, and the use of a single scanner model (and uniform acquisition protocols) for all participants. This latter factor may reduce imprecision or bias introduced by differences in image acquisition and reconstruction algorithms, which is a potential limitation of CT biomarkers.47

Our study has several limitations. The cross-sectional study design limits conclusions regarding the causality of the associations. Residual or unmeasured confounding cannot be excluded in this observational study, although our models were adjusted for relevant potential confounders. Because of the original recruitment strategy of the Framingham Heart Study, our sample is entirely of European ancestry, and our findings may not be generalizable to the population at large. The thoracic CT scan image acquisition algorithm was designed to enable interpretation of the lung parenchyma and pulmonary vasculature, but gated to optimize the primary goal of assessing coronary artery calcification. All scans were performed in the supine position, which may limit the ability to discriminate between ILAs and atelectatic changes in the dependent areas of the lung. To account for this, our study defined ILAs as changes that are present only in nondependent areas of the lung, which reduces the misclassification of atelectasis as ILA and is consistent with the definition of ILA used in prior publications.48 Assessment of ILA progression was performed on partial CT images, because the initial cardiac CTs were protocoled to cover the thorax only from roughly carina to diaphragm. This limits the evaluation of ILA/ILA progression in nonvisualized areas in both the most apical and basal lung zones, but this is unlikely to introduce substantial bias, because the same regions were consistently excluded for all participants. Blood volumes likely vary with thoracic size, and some prior studies have indexed absolute volumes (eg, BV5, TBV) against thoracic volume. Our study adjusted for predictors of thoracic volume (including age, height, weight, and sex) in all models, and we found similar results when examining the small vessel fraction (small vessel volume indexed to total blood vessel volume), which is less impacted by differences in thoracic volume. Although microvascular histologic pruning occurs in ILD, further research is needed to demonstrate more conclusively the extent to which small vessel vasculopathy is present in the setting of less severe ILAs. Finally, CT pruning cannot directly represent histologic pruning of the microvessels, because this image analysis method has a resolution limit of approximately 1 mm2. However, lower BV5 on CT is correlated with loss of pulmonary microvessels histologically (diameter, <500 μM), suggesting that CT pruning is, at minimum, an indirect indicator of histologic pruning.12

Although the presence of pulmonary vascular disease conclusively predicts poor outcomes in individuals with ILD,1,3,4,8,49 there is no effective method of screening for early pulmonary vascular changes and no effective specific treatments for pulmonary vasculopathy in ILD. CT imaging is ubiquitous in the evaluation of individuals with ILD or suspected ILD, and our findings may support its use as an attractive and practical method of identifying specific high-risk subgroups that may benefit from early therapy of this morbid process. Promisingly, CT vascular volume assessment is reproducible11 and can detect responses to surgical and medical therapy.50,51 Future research may elucidate the temporality of vascular and interstitial changes and determine the long-term prognostic implications of pruning on CT in ILD.

Interpretation

In this study of community-dwelling adults, more severe vascular pruning and lower total pulmonary blood vessel volumes on CT were associated with greater odds of ILA, ILA progression, and a restrictive pattern on spirometry. This provides new insight into the appearance of the pulmonary vessels in early interstitial disease and suggests that CT pruning may be an indicator of subtle pulmonary vasculopathy associated with progressive interstitial abnormalities in the lung.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: A. J. S. is the guarantor of the content of the manuscript, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. A. J. S. contributed to the conception of the research project, conducted the data analysis and interpretation, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. M. B. R. provided supervision for the project, including data analysis, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. M. B. R., M. A. M., G. M. H., and G. R. W. planned the overall study design of the project. G. R. W. and G. T. O. developed the CT sub-study within the Framingham Heart Study, which generated the radiographic vascular measures, provided expertise with pulmonary data from the Framingham Heart Study, and informed the statistical analysis. G. R. W., R. S. J. E., and A. A. B. provided technical expertise with radiographic vascular outcomes. G. M. H, R. W. H., and C. A. K. provided expertise with interstitial and pulmonary vascular data. W. L. provided expertise with demographic data in the Framingham Heart Study and contributed to the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, performed critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: A. J. S. is supported by grants from the NIH [grant F32 HL143819] and the American Lung Association. G. M. H. reports personal fees from Genentech, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gerson Lehrman Group, and Mitsubishi Chemical, outside the submitted work. G. R. W. is supported by the NIH [grants R01 HL122464 and R01 HL116473], and reports grants and other support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, Quantitative Imaging Solutions, PulmonX, Regeneron, ModoSpira, BTG Interventional Medicine, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Toshiba, GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work. G. R. W.’s spouse works for Biogen, which is focused on developing therapies for fibrotic lung disease. R. S. J. E. is supported by the NIH [grants 1R01 HL116931 and R01 HL116473], and reports personal fees from Toshiba, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eolo Medical, and Leuko Labs, outside the submitted work. He is also a founder and co-owner of Quantitative Imaging Solutions, which is a company that provides image-based consulting and develops software to enable data sharing. G. T. O. reports personal fees from AstraZeneca and grants from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. A. A. B. reports personal fees from Spiration, Daiichi, CRICO, and Elsevier, outside the submitted work. M. A. M. reports grants from the NIH, US EPA, during the conduct of the study; grants from PCORI, Kellogg Foundation, and US National Institute of Justice, outside the submitted work. M. B. R. is supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [grant K23 ES026204], the American Thoracic Society Foundation, and the American Lung Association. None declared (W. L., C. A. K., R. W. H.).

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Figure and e-Table can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Framingham Heart Study contract numbers N01-HC-25195 and HHSN268201500001I]; and Dr Synn [grant F32 HL143819] and the American Lung Association Catalyst Award.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Lettieri C.J., Nathan S.D., Barnett S.D., Ahmad S., Shorr A.F. Prevalence and outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2006;129(3):746–752. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plantier L., Cazes A., Dinh-Xuan A.-T., Bancal C., Marchand-Adam S., Crestani B. Physiology of the lung in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(147):170062. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0062-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koschel D.S., Cardoso C., Wiedemann B., Höffken G., Halank M. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Lung. 2012;190(3):295–302. doi: 10.1007/s00408-011-9361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi K., Taniguchi H., Ando M. Mean pulmonary arterial pressure as a prognostic indicator in connective tissue disease associated with interstitial lung disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0207-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price L.C., Devaraj A., Wort S.J. Central pulmonary arteries in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: size really matters. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1318–1320. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00272-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau E.M.T., Humbert M., Celermajer D.S. Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(3):143–155. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu X., Kim G.H., Salisbury M.L. Computed tomographic biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the future of quantitative analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(1):12–21. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0444PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farkas L., Gauldie J., Voelkel N.F., Kolb M. Pulmonary hypertension and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a tale of angiogenesis, apoptosis, and growth factors. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45(1):1–15. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0365TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsangaris I., Tsaknis G., Anthi A., Orfanos S.E. Pulmonary hypertension in parenchymal lung disease. Pulm Med. 2012;2012:684781. doi: 10.1155/2012/684781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon J.J., Olson A.L., Fischer A., Bull T., Brown K.K., Raghu G. Scleroderma lung disease. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22(127):6–19. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00005512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estépar R.S.J., Kinney G.L., Black-Shinn J.L. Computed tomographic measures of pulmonary vascular morphology in smokers and their clinical implications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(2):231–239. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0162OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahaghi F.N., Argemí G., Nardelli P. Pulmonary vascular density: comparison of findings on computed tomography imaging with histology. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(2):1900370. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00370-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ash S.Y., Rahaghi F.N., Come C.E. Pruning of the pulmonary vasculature in asthma: the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(1):39–50. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2426OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells J.M., Iyer A.S., Rahaghi F.N. Pulmonary artery enlargement is associated with right ventricular dysfunction and loss of blood volume in small pulmonary vessels in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(4) doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Washko G.R., Nardelli P., Ash S.Y. Arterial vascular pruning, right ventricular size and clinical outcomes in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(4):454–461. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201811-2063OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuoka S., Washko G.R., Yamashiro T. Pulmonary hypertension and computed tomography measurement of small pulmonary vessels in severe emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(3):218–225. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200908-1189OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Synn A.J., Li W., San José Estépar R. Radiographic pulmonary vessel volume, lung function, and airways disease in the Framingham Heart Study. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(3):1900408. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00408-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Synn A.J., Zhang C., Washko G.R. Cigarette smoke exposure and radiographic pulmonary vascular morphology in the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(6):698–706. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201811-795OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kliment C.R., Araki T., Doyle T.J. A comparison of visual and quantitative methods to identify interstitial lung abnormalities. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunninghake G.M., Hatabu H., Okajima Y. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2192–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1216076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice M.B., Li W., Schwartz J. Ambient air pollution exposure and risk and progression of interstitial lung abnormalities: the Framingham Heart Study. Thorax. 2019;74(11):1063–1069. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Araki T., Putman R.K., Hatabu H. Development and progression of interstitial lung abnormalities in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(12):1517–1522. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2523OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Washko G.R., Lynch D.A., Matsuoka S. Identification of early interstitial lung disease in smokers from the COPDGene Study. Acad Radiol. 2010;17(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putman R.K., Hatabu H., Araki T. Association between interstitial lung abnormalities and all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2016;315(7):672–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aaron S.D., Dales R.E., Cardinal P. How accurate is spirometry at predicting restrictive pulmonary impairment? Chest. 1999;115(3):869–873. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allison P.D. 2nd ed. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 2012. Logistic Regression Using SAS: Theory and Application. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice M.B., Li W., Dorans K.S. Exposure to traffic emissions and fine particulate matter and computed tomography measures of the lung and airways. Epidemiology. 2018;29(3):333–341. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li W., Dorans K.S., Wilker E.H. Short-term exposure to ambient air pollution and biomarkers of systemic inflammation: the Framingham Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(9):1793–1800. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsao C.W., Vasan R.S. Cohort profile: the Framingham Heart Study (FHS): overview of milestones in cardiovascular epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(6):1800–1813. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santos S., Peinado V.I., Ramírez J. Characterization of pulmonary vascular remodelling in smokers and patients with mild COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(4):632–638. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00245902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Washko G.R., Hunninghake G.M., Fernandez I.E. Lung volumes and emphysema in smokers with interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(10):897–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lederer D.J., Enright P.L., Kawut S.M. Cigarette smoking is associated with subclinical parenchymal lung disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)-lung study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(5):407–414. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1966OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scarrow G.D. The pulmonary angiogram in chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Clin Radiol. 1966;17(1):54–67. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(66)80123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cordasco E.M., Beerel F.R., Vance J.W., Wende R.W., Toffolo R.R. Newer aspects of the pulmonary vasculature in chronic lung disease: a comparative study. Angiology. 1968;19(7):399–407. doi: 10.1177/000331976801900703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobson G., Turner A.F., Balchum O.J., Jung R. Vascular changes in pulmonary emphysema: the radiologic evaluation by selective and peripheral pulmonary wedge angiography. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1967;100(2):374–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakao S., Voelkel N.F., Tatsumi K. The vascular bed in COPD: pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular alterations. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(133):350–355. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacob J., Bartholmai B.J., Rajagopalan S. Mortality prediction in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evaluation of computer-based CT analysis with conventional severity measures. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(1):1601011. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01011-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacob J., Bartholmai B.J., Rajagopalan S. Automated quantitative computed tomography versus visual computed tomography scoring in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis validation against pulmonary function. J Thorac Imaging. 2016;31(5):304–311. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacob J., Bartholmai B.J., Rajagopalan S. Evaluation of computer-based computer tomography stratification against outcome models in connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease: a patient outcome study. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0739-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacob J., Bartholmai B.J., Rajagopalan S. Serial automated quantitative CT analysis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: functional correlations and comparison with changes in visual CT scores. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(3):1318–1327. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5053-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacob J., Pienn M., Payer C. Quantitative CT-derived vessel metrics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a structure–function study. Respirology. 2019;24(5):445–452. doi: 10.1111/resp.13485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacob J., Bartholmai B.J., Egashira R. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: identification of key prognostic determinants using automated CT analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0418-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller E.R., Putman R.K., Vivero M. Histopathology of interstitial lung abnormalities in the context of lung nodule resections. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(7):955–958. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1679LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanski M., Arheden H., Wuttge D.M., Bozovic G., Hesselstrand R., Ugander M. Pulmonary blood volume indexed to lung volume is reduced in newly diagnosed systemic sclerosis compared to normals: a prospective clinical cardiovascular magnetic resonance study addressing pulmonary vascular changes. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15(1):86. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lynch D.A., Godwin J.D., Safrin S. High-resolution computed tomography in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and prognosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(4):488–493. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1756OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose L., Prins K.W., Archer S.L. Survival in pulmonary hypertension due to chronic lung disease: influence of low diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2019;38(2):145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bodduluri S., Reinhardt J.M., Hoffman E.A., Newell J.D., Bhatt S.P. Recent advances in computed tomography imaging in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(3):281–289. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201705-377FR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatabu H., Hunninghake G.M., Lynch D.A. Interstitial lung abnormality: recognition and perspectives. Radiology. 2019;291(1):1–3. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018181684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collum S.D., Amione-Guerra J., Cruz-Solbes A.S. Pulmonary hypertension associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current and future perspectives. Can Respir J. 2017;2017:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2017/1430350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahaghi F., Come C., Ross J. Morphologic response of the pulmonary vasculature to endoscopic lung volume reduction. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2015;2(3):214–222. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.2.3.2014.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rahaghi F.N., Winkler T., Kohli P. Quantification of the pulmonary vascular response to inhaled nitric oxide using noncontrast computed tomography imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(1):8338. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.008338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.