Highlights

-

•

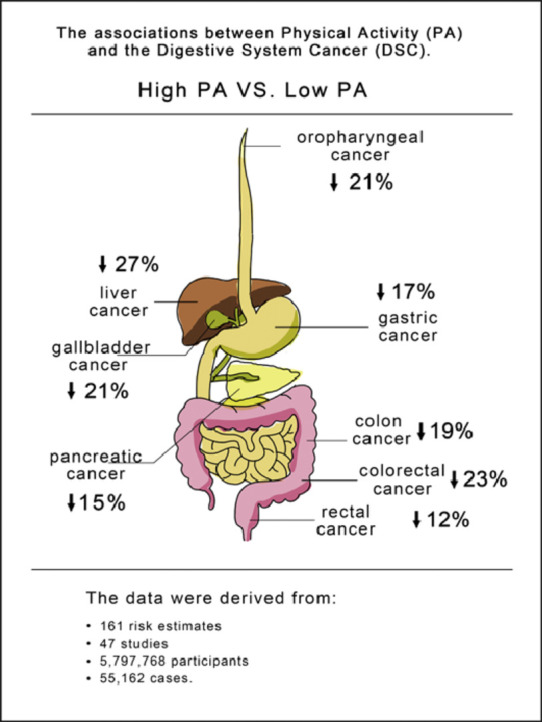

The current systematic review analyzed the data from 161 risk estimates in 47 studies involving 5,797,768 participants and 55,162 cases.

-

•

Updated evidence suggests that a moderate to high physical activity level is a common protective factor that can significantly lower the overall risk of digestive-system cancer.

-

•

Limited evidence suggests that meeting the international physical activity guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of digestive-system cancer.

Keywords: Digestive-system cancer, Meta-analysis, Physical activity

Abstract

Background

Physical activity (PA) may have an impact on digestive-system cancer (DSC) by improving insulin sensitivity and anticancer immune function and by reducing the exposure of the digestive tract to carcinogens by stimulating gastrointestinal motility, thus reducing transit time. The current study aimed to determine the effect of PA on different types of DSC via a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, we searched for relevant studies in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure. Using a random effects model, the relationship between PA and different types of DSC was analyzed.

Results

The data used for meta-analysis were derived from 161 risk estimates in 47 studies involving 5,797,768 participants and 55,162 cases. We assessed the pooled associations between high vs. low PA levels and the risk of DSC (risk ratio (RR) = 0.82, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 0.79–0.85), colon cancer (RR = 0.81, 95%CI: 0.76–0.87), rectal cancer (RR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.80–0.98), colorectal cancer (RR = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.69–0.85), gallbladder cancer (RR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.64–0.98), gastric cancer (RR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.76–0.91), liver cancer (RR = 0.73, 0.60–0.89), oropharyngeal cancer (RR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.72–0.87), and pancreatic cancer (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.78–0.93). The findings were comparable between case-control studies (RR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.68–0.78) and prospective cohort studies (RR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.80–0.91). The meta-analysis of 9 studies reporting low, moderate, and high PA levels, with 17 risk estimates, showed that compared to low PA, moderate PA may also reduce the risk of DSC (RR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.80–1.00), while compared to moderate PA, high PA seemed to slightly increase the risk of DSC, although the results were not statistically significant (RR = 1.11, 95%CI: 0.94–1.32). In addition, limited evidence from 5 studies suggested that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC (RR = 0.96, 95%CI: 0.91–1.02).

Conclusion

Compared to previous research, this systematic review has provided more comprehensive information about the inverse relationship between PA and DSC risk. The updated evidence from the current meta-analysis indicates that a moderate-to-high PA level is a common protective factor that can significantly lower the overall risk of DSC. However, the reduction rate for specific cancers may vary. In addition, limited evidence suggests that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC. Thus, future studies must be conducted to determine the optimal dosage, frequency, intensity, and duration of PA required to reduce DSC risk effectively.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Digestive-system cancer (DSC) includes cancers of the digestive tract (mouth, throat, oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colorectum) and the digestive accessory organs (pancreas, gallbladder, and liver).1,2 DSC, which is considered a worldwide health problem, is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.3 In 2018, approximately 319,160 new cases and 160,820 DSC-related deaths were recorded in the United States.4 In the past 20 years, colon, rectal, stomach, and liver cancers were among the top 10 leading cancers worldwide, and colorectal, liver, and stomach cancers accounted for 920,000, 577,000, and 535,000 deaths, respectively.5 In addition, the 5-year survival rate of patients with DSC is less than 20%.6 The high prevalence and risk of death and poor prognosis underscore the need to identify possible measures in primary care that can prevent DSC.7

Research data have shown that healthy lifestyle habits,7 such as proper diet,8,9 smoking cessation,10,11 decrease in body mass index,12,13 alcohol avoidance,14 prevention of obesity,15,16 and increased physical activity (PA), may reduce the risk of DSC. A significant body of evidence has revealed that PA plays a crucial role in maintaining and enhancing health status, particularly because the global epidemic of sedentary lifestyle is increasing. Moreover, good lifestyle habits have been found to be an extremely effective and affordable method for preventing and treating several noncommunicable chronic diseases.17 In addition, 5 years ago, World Health Organization reports showed a 7% decrease in overall cancer risk, with DSC having the highest rate of reduction.18 The protective effect of PA against cancer may be mediated by decreasing systemic inflammation, thereby leading to favorable immunomodulation.19

In the past decade, a series of epidemiological studies20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 has investigated the relationship between PA and the risk of DSC, including colon cancer,23,24,26,28, 29, 30,37,41,43,47,52,54,56, 57, 58,63 rectal cancer,21,23, 24, 25, 26,31,32,34,43,46,52,61 colorectal cancer,22,23,34,36,37,39,46,49,52,53,59,63,64,67 oesophageal cancer,21,24,35,42,45,50,59,65 gallbladder cancer,27,65 gastric cancer,21,38,44,45,47,50,59,60,65 oropharyngeal cancer,24,31,51,55,65 liver cancer,24,27,47,65 and pancreatic cancer.24, 25, 26,32,33,40,47, 48, 49,55,59,64, 65, 66

Some studies have shown that PA may reduce the risk of certain types of digestive cancer, such as oesophagea,1 gastric,21 colorectal,22 and liver cancer.23 However, systematic reviews of DSC cancer were conducted 5 years ago,24, 25, 26 and in that review, data on some DSCs, such as gallbladder, oral cavity, and pharyngeal cancers were missing. Since that time, a comprehensive study that provides more complete information of the effect of PA on the risk of DSC has not been undertaken. Therefore, we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis of multiple studies27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72 in order to provide and quantify updated data on the relationship between PA and DSC risk.

2. Materials and methods

The protocol for our review is available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018104367.

2.1. Literature search

A meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.73 To quantify the association between PA and the risk of DSC, 2 authors (FX and JH) independently searched for studies published between January 2008 and November 2018 that were cited in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure. In case of disagreement between the 2 authors, a final consensus was reached via team discussion.

Studies were retrieved using medical subject headings combined with entry terms. We used the following terms for PA: “PA”, “Exercises”, “Activities, Physical”, “Activity, Physical”, “Physical Activities”, “Exercise, Physical”, “Exercises, Physical”, “Physical Exercise”, “Physical Exercises”, “Acute Exercise”, “Acute Exercises”, “Exercise, Acute”, “Exercises, Acute”, “Exercise, Isometric”, “Exercises, Isometric”, “Isometric Exercises”, “Isometric Exercise”, “Exercise, Aerobic”, “Aerobic Exercise”, “Aerobic Exercises”, “Exercises, Aerobic”, “Exercise Training”, “Exercise Trainings”, “Training, Exercise”, and “Trainings, Exercise”. Subsequently, we used the AND operator to combine these terms with the following terms for DSC outcomes: “DSC”, “Digestive System Neoplasm”, “Digestive System Neoplasms”, “Neoplasm, Digestive System”, “Neoplasms, Digestive System”, “Cancer of Digestive System”, “DSCs”, “Cancer, Digestive System”, and “Cancers, Digestive System”. Similarly, we used the AND operator to combine the PA terms with mouth cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, gallbladder cancer, liver cancer, oesophageal cancer, small intestine cancer, and colorectal cancer (Supplementary File 1). The search strategy used was based on research articles involving human subjects. An article was considered eligible if the reported relative risk estimate was equivalent to the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI) or data. Studies on DSC cancer survivors classified as reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, letters, practice guides, and news were excluded.

We defined PA based on the duration, domain, quality, frequency, and category of activities. The duration of activity was used to evaluate the time spent per week in PA. The assessment of energy expenditure was expressed in weekly metabolic equivalent tasks (METs). The quality of PA was based on the following categories: low PA (<600 METs), moderate PA (600–3000 METs), and high PA (>3000 METs).

2.2. Data extraction

To assess the possible differences in the relationship between PA and DSC, we extracted the risk estimates from each included study for each of the DSC subtypes, which allowed all DSC cases to be considered. Specifically, for each study, we obtained the last name of the first author, year of publication, study location, sample size, case numbers, cancer site, domains of PA, gender, timing of PA, high vs. low, high vs. moderate, and moderate vs. low category of PA, risk estimates (95%CI), and adjusted factors in each study. Gender was considered an independent sample in this study. Thus, the risk estimates for men and women were extracted independently. If a study reported high, moderate, and low domains of PA, data about the estimates of all domains were collected.

Of the 47 studies that met the inclusion criteria, seven36,47,53,57,63,64,69 reported risk estimates with high PA levels, and they were considered the reference group. Compared with other studies, we converted the relative risk estimates (RRi) to their reciprocal values. The rest of the studies were extracted directly with reference to high PA levels.

2.3. Risk-of-bias assessment

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for the assessment of study quality, which was independently evaluated by 2 investigators (FX and JH). If there was a disagreement, the 3rd experienced investigator (FY) joined the discussion until a consensus was reached. The total NOS score was 9, which was suitable for evaluating case-control studies (selection, comparability, and exposure) and cohort studies (selection, comparability, and outcome). Studies with a quality score ≤4 were categorized as low-quality studies, and those with a score of ≥5 were categorized as high-quality studies.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The hazard ratios and odds ratios were presented as estimates of the RRi for the measurement of the association between PA and DSC risk. When RRi were available, we used the adjusted risk estimates reported in the original literature. Otherwise, the RRi and 95%CIs were calculated using Stata software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). The natural logarithms of the risk estimates log (RRi) were calculated on the basis of corresponding standard error (SE): si = (log(upper 95%CI bound of RR)–log(RR))/1.96. A random effects model was used to account for the log(RRi)s, which was weighted by wi = 1/(si2 + t2) (si = error of log (RRi), t2 = population variance).74 Q- and I2-statistics were used to assess heterogeneity.74 In addition, to examine any publication bias, we used funnel plots, the Begg rank test,75 and the Egger regression test.76 p was considered statistically significant at a 0.05 level. In addition, to ensure the authenticity of publication, we performed a sensitivity analysis using the trim-and-fill method, as presented by Duval and Tweedie,77 to evaluate any publication bias.

A sub-analysis was conducted to investigate whether the summary risk estimate was affected by cancer site (colon, rectum, colorectum, gallbladder, stomach, liver, pancreas, or oral cavity and pharynx), PA level (high, moderate, or low), international PA guidelines (above or below 150 min/week or 600 METs-min/week or 10 METs-h/week), study design (prospective, case control), gender (men, women), region of the study (North America, Europe, Australia, Asia, or Middle East), PA domain (recreational, occupational), timing for PA (recent, past, or consistent PA), adjustment for smoking (yes, no), body mass index (BMI) (yes, no), and alcohol intake (yes, no). To investigate the impact of prespecified potentially influential methodological factors on summary risk estimates, a random effects meta-analysis regression was used to analyze all 161 risk estimates.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software (Version 11.0; Stata). The RRs were reported along with 95%CI. The statistical significance was set at a 0.05 level.

3. Results

Our initial search identified 8322 articles, of which 2752 duplicates were excluded, and 5488 articles were further excluded after browsing the titles and abstracts. The 82 remaining studies were assessed in depth. A total of 47 studies were included in our final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of identification and selection of eligible studies.

Supplementary Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the 161 risk factors in 28 prospective studies27,28,31,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45,47,49, 50, 51, 52,55, 56, 57,59,61,63,66,68,70 and 19 case-control studies29,30,32, 33, 34,48,51,53, 54, 55,58,60,62,64,65,67,69,71,72 that described the association between PA and DSC risk. The studies evaluated 9 cancer sites, including the colon,29,30,32,34, 35, 36,43,47,49,53,57,59,62, 63, 64,69 rectum,27,29, 30, 31, 32,37,38,40,49,52,57,67 colorectum,28,29,40,42,43,45,52,55,57,58,63,67,68,71 oesophagus,30,41,48,51,55,65,71, gallbladder,33,71 stomach,27,44,50,51,53,55,65,66,71 oropharynx,30,37,56,61,71 liver,30,33,53,71 and pancreas.30, 31, 32,38,39,46,53, 54, 55,60,65,70, 71, 72 This meta-analysis included a total of 5,797,768 participants and 55,162 cases, and 23 studies examined more than 1 DSC endpoint. Moreover, 13 studies investigated more than 1 PA domain; 11 studies presented results stratified according to gender. A total of 24 studies assessed recent PA, 10 studies collected information about past PA, and 18 studies evaluated consistent PA over time. Smoking status and BMI were adjusted in 33 and 30 studies, respectively.

We summarized 161 risk estimates using the random effects model in 47 studies, and an 18% reduction was observed in DSC risk for those with high PA levels compared to those with low PA levels (RR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.79–0.85), with moderate between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 57%, p < 0.001 for heterogeneity across all studies), for colon cancer (RR = 0.81, 95%CI: 0.76–0.87), rectal cancer (RR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.80–0.98), colorectal cancer (RR = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.69–0.85), gallbladder cancer (RR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.64–0.98), gastric cancer (RR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.76–0.91), liver cancer (RR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.60–0.89), oropharyngeal cancer (RR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.72–0.87), and pancreatic cancer (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.78–0.93). No statistically significant association was observed between PA levels and oesophageal cancer (RR = 0.84, 95%CI: 0.66–1.07) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Publication bias was considered using the funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. 2A), the Begg rank test (p = 0.216) (Supplementary Fig. 2B), the Egger regression test (p = 0.024) (Supplementary Fig. 2C), and the trim-and-fill method (p < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 2D).

We independently analyzed prospective and case-control studies. A statistically significant inverse relationship was found between PA level and DSC in prospective studies (RR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.80–0.91; I2 = 42.5%) and case-control studies (RR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.68–0.78; I2 = 49.2%). All differences had a p < 0.001 (Supplementary Fig. 3). In terms of gender difference, the summary risk estimate of women (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.78–0.93, p < 0.001) was more likely to be similar to that of men (RR = 0.84, 95%CI: 0.80–0.88, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

In terms of the effects of differing levels of PA on the risk of DSC, the meta-analysis of 9 studies27,31,32,40,48,59, 60, 61,66 reporting low, moderate, and high PA levels, with 17 risk estimates, showed that compared to low PA, moderate PA may also reduce the risk of DSC (RR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.80–1.00) (Supplementary Fig. 5) and that compared to moderate PA, high PA seemed to slightly increase the DSC risk, although the results were not statistically significant (RR = 1.11, 95%CI: 0.94–1.32) (Supplementary Fig. 6). In addition, limited evidence from 5 studies30,40,49,58,64 suggested that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC (RR = 0.96, 95%CI: 0.91–1.02), with high between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 99.7%) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

The study quality is shown in Table 1. The average quality score was 5.60 (SD = 0.83, median = 5.00). The included studies had multiple potential confounders, such as smoking (39/47), alcohol drinking (37/47), BMI (30/47), and family histories of DSC (19/47). Most of the studies corrected for the symptoms of DSC. Moreover, 18 studies included clear diagnoses and definitions of DSC, and the overall evaluation score was more than 6, which indicated high quality, according to the questionnaire survey. However, whether the case group was a continuous case and whether it was representative were not discussed.

Table 1.

Quality of studies according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

| Study | Selection (max score 4) | Comparability (max score 2) | Exposure (case-control) or outcome (cohort) (max score 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective studies | |||

| Nunez et al. (2018)64 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Wu et al. (2018)70 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Kunzmann et al. (2018)27 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Eaglehouse et al. (2017)40 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Nomura et al. (2016)63 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Mok et al. (2016)57 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Keum et al. (2016)2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Aleksandrova et al. (2014)29 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Morikawa et al. (2013)58 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Arem et al. (2014)30 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Behrens et al. (2013)33 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Nakamura et al. (2011)60 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Morrison et al. (2011)59 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Heinen et al. (2011)46 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Huerta et al. (2017)50 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Wolin et al. (2010)69 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Batty et al. (2010)32 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Jiao et al. (2009)54 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Leitzmann et al. (2009)55 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Hermann et al. (2009)47 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Batty et al. (2009)31 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Sjödahl et al. (2008)66 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Calton et al. (2008)39 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Howard et al. (2008)49 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Inoue et al. (2008)53 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Leitzmann et al. (2008)56 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Yun et al. (2008)71 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Nilsen et al. (2008)62 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Case-control studies | |||

| Zhang et al. (2009)72 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Parent et al. (2011)65 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Nicolotti et al. (2011)61 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Boyle et al. (2011)35 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Boyle et al. (2011)36 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Etemadi et al. (2012)41 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Boyle et al. (2012)34 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Tayyem et al. (2013)67 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Brenner et al. (2014)38 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Hang et al. (2015)45 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Hilal et al. (2016)48 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Golshiri et al. (2016)42 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Aithal et al. (2017)28 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Bravi et al. (2017)37 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Huerta et al. (2017)50 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Ibáñez-Sanz et al. (2017)52 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Turati et al. (2017)68 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Gunathilake et al. (2018)43 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Gunathilake et al. (2018)44 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the included studies that assessed the relationship between DSC risk and differing levels of PA (high vs. low PA level, moderate vs. low PA level, and high vs. moderate PA level). There were 12 studies in Asia,28,40,42, 43, 44, 45,53,57,60,67,70,71 three in Australia,34,36,64 sixteen in Europe,27,29,31,32,37,38,46,47,50, 51, 52,59,61,62,66,68 one in the Middle East,41 and thirteen in North America;30,33,39,48,49,54, 55, 56,58,63,65,69,72 these yielded a total of 52, 12, 48, 2, and 47 risk estimates, respectively. In the sub-analysis of DSC, previous PA (RR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.78–0.95; I2 = 40%), consistent PA over time (RR = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.72–0.82; I 2 = 48%), and recent PA (RR = 0.84, 95%CI: 0.80–0.88; I2 = 60%) significantly reduced DSC risk. Similarly, the inverse relationship between cancer and activity types in the PA domain was also statistically significant, with variables including total activity (RR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.75–0.86), recreational activity (RR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.79–0.86), and occupational activity (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.76–0.94). We pooled the findings from these studies and found a significant difference in terms of the gender, geographic region of the study, BMI, smoking status, and alcohol consumption after adjustment (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Summary risk estimates of high vs. low physical activity (PA), stratified by selected characteristics.

| Stratification variable | Number of risk estimates included | Relative risk (95% confidence interval) for high vs. low PA | I² (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total digestive-system cancer | 161 | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | 57 | <0.001 |

| Cancer site | ||||

| Colon cancer | 33 | 0.81 (0.76–0.81) | 41 | <0.001 |

| Rectal cancer | 24 | 0.88 (0.80–0.98) | 47 | |

| Colorectal cancer | 23 | 0.77 (0.69–0.85) | 82 | |

| Gallbladder cancer | 2 | 0.79 (0.64–0.98) | 0 | |

| Gastric cancer | 17 | 0.83 (0.76–0.91) | 33 | |

| Liver cancer | 5 | 0.73 (0.60–0.89) | 56 | |

| Oral cavity and pharynx cancer | 11 | 0.79 (0.72–0.87) | 32 | |

| Pancreas cancer | 33 | 0.85 (0.78–0.93) | 45 | |

| Esophagus cancer | 13 | 0.84 (0.66–1.07) | 62 | |

| Study design | ||||

| Prospective studies | 98 | 0.88 (0.85–0.91) | 43 | <0.001 |

| Case-control studies | 63 | 0.73 (0.68–0.78) | 49 | |

| Gendera | ||||

| Men | 63 | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | 41 | <0.001 |

| Women | 38 | 0.85 (0.78–0.93) | 51 | |

| Study geographic region | ||||

| Asia | 52 | 0.75 (0.69–0.81) | 67 | <0.001 |

| Europe | 48 | 0.85 (0.81–0.90) | 54 | |

| Australia | 12 | 0.77 (0.69–0.87) | 0 | |

| Middle East | 2 | 0.20 (0.01–3.07) | 80 | |

| North America | 47 | 0.86 (0.81–0.93) | 43 | |

| PA domain | ||||

| Total activity | 34 | 0.80 (0.75–0.86) | 41 | <0.001 |

| Recreational activity | 107 | 0.82 (0.79–0.86) | 65 | |

| Occupational activity | 20 | 0.85 (0.76–0.94) | 0 | |

| Timing in life of PA | ||||

| Recent | 76 | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | 60 | <0.001 |

| Consistent over time | 59 | 0.77 (0.72–0.82) | 48 | |

| Past | 26 | 0.86 (0.78–0.95) | 40 | |

| Adjustment for body mass index | ||||

| Adjusted | 120 | 0.82 (0.79–0.86) | 59 | <0.001 |

| Not adjusted | 41 | 0.80 (0.74–0.87) | 49 | |

| Adjustment for smoking | ||||

| Adjusted | 139 | 0.83 (0.80–0.86) | 49 | <0.001 |

| Not adjusted | 22 | 0.77 (0.69–0.87) | 76 | |

| Adjustment for alcohol | ||||

| Adjusted | 115 | 0.84 (0.81–0.87) | 50 | <0.001 |

| Not adjusted | 46 | 0.77 (0.71–0.84) | 63 |

Note: The p value for difference across strata of selected characteristics was estimated from random effects meta-regression comparing a model that included the stratification variable with the null model that did not include the stratification variable.

Studies that include both men and women were not considered for subgroup analysis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Association between PA and DSC risk

Because more people want exercise to be included in clinical cancer care,78,79 the 2010 American College of Sports Medicine International Multidisciplinary Roundtable recommendations followed the 2008 Guidelines for Physical Activities of Adults with Chronic Illnesses, with a goal of at least 150 min/week of aerobic activity. This exercise recommendation is believed to be safe during and after cancer treatment and can improve some health outcomes.80,81 In 2018, the American College of Sports Medicine International Multidisciplinary Roundtable on Physical Activity and Cancer Prevention and Control was tasked with updating the recommendations based on available evidence. One of the key reviews focused on evidence from the exercise method, including aerobic exercise, resistance exercise, and aerobic plus resistance training, as it related to health outcomes.82 Thus, our meta-analysis selected exercise patterns based on differing levels of PA (high vs. low PA, moderate vs. low PA, and high vs. moderate PA, as well as on meeting vs. not meeting the international PA guidelines). We examined cancer risk according to cancer site, geographic region, PA intensity, timing of PA, and type of PA assessment. A random effects meta-analysis of the association between PA and DSC was conducted, and our results showed that PA is a protective factor in DSC and that a high PA level was associated with a decrease in DSC risk by 18%, which is consistent with a previous prospective study showing that PA can reduce the risk of DSC by at least 17%.12 Specifically, our results regarding the significant effects of PA on reducing the risk of DSC are consistent with those from previous studies that have investigated the relationship between PA and risk of a single type of DSC, such as colon,83 rectal,84 colorectal,85 gastric,86 pancreatic,24 and liver cancer.23 However, our results showed that the effect of PA on colorectal,85 liver,23 and pancreatic cancer24 yielded a more pronounced risk reduction, whereas there was less risk reduction with increased PA for the other DSCs, such as colon,83 gastric,86 and oesophageal cancer.26 More important, our study is the first to report that PA has an effect on the risk of gallbladder cancer and oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer, with a risk reduction of 21%.

In addition to the finding that a high PA level was associated with a decrease in DSC risk, our study also assessed the association between different levels of PA and DSC risk. Our results indicated that compared to low PA, moderate PA may also effectively reduce the risk of DSC. However, compared to moderate PA, high PA seemed to slightly increase the DSC risk, although the results were not statistically significant. Some evidence has suggested that high-intensity PA may have a negative effect on the human immune system.87 Therefore, intensified PA may suppress the immune system's ability to detect and destroy DSC-related malignant cells. Furthermore, our findings, based on a limited number of studies, suggested that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC. Our finding is inconsistent with other research, where meeting or exceeding PA guidelines was found to be associated with lowered cancer risk.88 This may be because the sample size of our included studies was small and between-study heterogeneity was high (I2 = 99.7%). Therefore, future studies should determine the optimal level of PA required to reduce DSC risk effectively.

In our review, there was strong evidence showing that the association between PA and DSC risk varied according to the study's design, the gender of the participants, the geographic region in which the study was conducted, the PA intensity, the timing of PA, the type of PA assessment, and the adjustment factors (such as smoking, BMI, and alcohol). The influence of these factors was examined in a previous meta-analysis of PA and prostate,89 gastric,86 and gastroesophageal cancer.20 The findings in those studies were similar to ours in that a statistically significant association was found between study design89 and gender86 as well as PA domain.20 In addition, we examined whether smoking, BMI, and alcohol mediated the inverse relationship between PA and risk of DSC by comparing risk estimates that accounted for these factors to those without those factors. Notably, the inverse association between PA and DSC was not attenuated when the meta-analysis was restricted only to datasets adjusted for smoking, BMI, and alcohol consumption, which is in accordance with a previous meta-analysis of PA and pancreatic cancer.24 Our results indicate that the biological mechanisms by which PA decreases the risk of DSC are not strictly regulated by smoking, BMI, or alcohol control.

In our review, the inverse association between PA and DSC was slightly more evident in men than in women, and the treatment of DSC significantly differed in terms of gender. One possible explanation for this finding is that men had higher family communication scores than women, and men were more likely not to talk about their negative symptoms, such as side effects or relapses, during the quantitative phase.90 This condition may indicate a relationship between gender and role because negative symptoms can significantly affect the physical status and survival rates of patients.91

4.2. Biological mechanisms

The molecular pathophysiology of DSC implies an inflammatory mechanism, which involves the interaction among various inflammatory cells, immune cells, proinflammatory mediators, cytokines, and chemokines, and this may lead to signaling toward tumor cell proliferation and growth.91 The findings in the present study can be explained by some biological mechanisms, such as increased estrogen and testosterone levels,92 enhanced anti-oxidant defences, decreased circulating insulin levels,93 reduced exposure of the digestive tract to carcinogens,93 and increased plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels.94 In addition, PA may have an impact on DSC via the pro-inflammatory pathway, which is mediated by reducing the cyclooxygenase-2 inflammatory response.95, 96, 97 The exact mechanisms underlying the association between high PA level and reduced DSC risk still have not been fully elucidated. However, PA is believed to improve the number or the function of natural killer cells.97

The consistency of risk reduction in all types of DSC observed in our study indicates that PA is a common protective factor for these cancers. DSCs have common risk factors, even though they have distinct etiologies, and this result is supported by studies showing that some factors, such as smoking 1–10 cigarettes per day over a lifetime,98 alcohol intake,99, 100, 101 excessive food intake,102, 103, 104 and the use of aspirin/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs105, 106, 107 are correlated with an increased risk of developing DSC by up to 2.34 times. Thus, all these factors are positively correlated with DSC and its subtypes.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

One novel aspect of our study is that we used the known varieties of DSCs in our meta-analysis of the association between differing levels of PA and DSC risk. Another strength is that a large sample size was used. Thus, an extensive information sub-analysis was performed. Moreover, stratification according to the subtypes of DSC, study design, PA domain, gender, and geographic region, as well as adjustment for BMI, smoking, and alcohol intake, was performed. Thus, the results of our study may be more informative and robust than those of a small-scale study based on a specific DSC.

A limitation of our study is that the category of PA groups covered significant variations in PA volume. Specifically, several studies do not have a moderate PA classification, and most were classified as active PA or inactive PA, with or without PA, and possible and impossible PA. Such variations did not allow us to identify the specific types and intensity of PA that might affect its impact on DSC risk. Another limitation was that information about the stage of DSCs could not be extracted. Thus, it could not be determined what effects PA may have to prevent DSC from developing to the next stage.

5. Conclusion

Our systematic review has provided additional comprehensive information about the inverse relationship between PA and DSC risk. The updated evidence from our meta-analysis indicates that a moderate-to-high PA level is a common protective factor that can significantly lower the overall risk of DSC. However, the reduction rate for specific cancers may vary. In addition, limited evidence suggests that meeting the international PA guidelines might not significantly reduce the risk of DSC. Thus, future studies should be conducted in order to determine the optimal dosage, frequency, intensity, and duration of PA that can reduce the risk of DSC.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Xingang Lu for providing advice about the analysis. We also thank Ping Lu for guidance and Professor Roger Adams from the University of Canberra for proofreading the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81774443, 31870936) and the 3-year Development Plan Project for Traditional Chinese Medicine (ZY(2018-2020)-CCCX-2001-05).

Authors’ contributions

All the authors participated in conceiving and designing the project. FX, JH, CG, and ZC performed the search and meta-analysis; FY, MF, and JH contributed to data analysis and interpretation; YY drafted the manuscript, which was revised by all co-authors. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the presentation of the order of the author.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.09.009.

Contributor Information

Fei Yao, Email: doctoryaofei@126.com.

Jia Han, Email: Jia.Han@canberra.edu.au.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.O'Neill L, Moran J, Guinan EM, Reynolds JV, Hussey J. Physical decline and its implications in the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12:601–618. doi: 10.1007/s11764-018-0696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keum N, Bao Y, Smith-Warner SA. Association of physical activity by type and intensity with digestive-system cancer risk. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1146–1153. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang S, Liu T, Cheng Y, Bai Y, Liang G. Immune cell infiltration as a biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of digestive-system cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:3639–3649. doi: 10.1111/cas.14216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer Groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524–548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A, Ward EM, Johnson CJ. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2014, featuring survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djx030. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson A, Hayes J, Frampton C, Potter J. Modifiable lifestyle factors that could reduce the incidence of colorectal cancer in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2016;129:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grosso G, Bella F, Godos J. Possible role of diet in cancer: systematic review and multiple meta-analyses of dietary patterns, lifestyle factors, and cancer risk. Nutr Rev. 2017;75:405–419. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekmekcioglu C, Wallner P, Kundi M, Weisz U, Haas W, Hutter HP. Red meat, diseases, and healthy alternatives: a critical review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:247–261. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1158148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdel-Rahman O, Helbling D, Schöb O. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for the development of and mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma: an updated systematic review of 81 epidemiological studies. J Evid Based Med. 2017;10:245–254. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montazeri Z, Nyiraneza C, El-Katerji H, Little J. Waterpipe smoking and cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2017;26:92–97. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben Q, An W, Jiang Y. Body mass index increases risk for colorectal adenomas based on meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:762–772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robsahm TE, Aagnes B, Hjartåker A, Langseth H, Bray FI, Larsen IK. Body mass index, physical activity, and colorectal cancer by anatomical subsites: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2013;22:492–505. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328360f434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roerecke M, Shield KD, Higuchi S. Estimates of alcohol-related oesophageal cancer burden in Japan: systematic review and meta-analyses. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93 doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.142141. 329–38C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fock KM, Khoo J. Diet and exercise in management of obesity and overweight. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(Suppl. 4):S59–S63. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Key TJ, Schatzkin A, Willett WC, Allen NE, Spencer EA, Travis RC. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of cancer. Pub Health Nutr. 2004;7:187–200. doi: 10.1079/phn2003588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuka V, Daňková M, Riegel K, Matoulek M. Physical activity: the holy grail of modern medicine? Vnitr Lek. 2017;63:729–736. [in Czech] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu L, Shi Y, Li T. Leisure-time physical activity and cancer risk: evaluation of the WHO's recommendation based on 126 high-quality epidemiological studies. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:372–378. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubans D, Richards J, Hillman C. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: a systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics. 2016;138 doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam S, Hart AR. Does physical activity protect against the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma? A review of the literature with a meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1–10. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abioye AI, Odesanya MO, Abioye AI, Ibrahim NA. Physical activity and risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:224–229. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillis C, Buhler K, Bresee L. Effects of nutritional prehabilitation, with and without exercise, on outcomes of patients who undergo colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:391–410. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin ZZ, Xu YC, Liu CX, Lu XL, Wen FY. Physical activity and liver cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin J Sport Med. 2021;31:86–90. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Behrens G, Jochem C, Schmid D, Keimling M, Ricci C, Leitzmann MF. Physical activity and risk of pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:279–298. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farris MS, Mosli MH, McFadden AA, Friedenreich CM, Brenner DR. The association between leisure time physical activity and pancreatic cancer risk in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24:1462–1473. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh S, Devanna S, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, Murad MH, Iyer PG. Physical activity is associated with reduced risk of esophageal cancer, particularly esophageal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunzmann AT, Mallon KP, Hunter RF. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour and risk of oesophago-gastric cancer: a prospective cohort study within UK Biobank. Unit Euro Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:1144–1154. doi: 10.1177/2050640618783558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aithal RR, Shetty RS, Binu VS, Mallya SD, Rajgopal Shenoy K, Nair S. Colorectal cancer and its risk factors among patients attending a tertiary care hospital in Southern Karnataka, India. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aleksandrova K, Pischon T, Jenab M. Combined impact of healthy lifestyle factors on colorectal cancer: a large European cohort study. BMC Med. 2014;12:168. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0168-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arem H, Moore SC, Park Y. Physical activity and cancer-specific mortality in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study cohort. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:423–431. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batty GD, Kivimaki M, Morrison D. Risk factors for pancreatic cancer mortality: extended follow-up of the original Whitehall Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18:673–675. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Kivimaki M, Marmot M, Davey Smith G. Walking pace, leisure time physical activity, and resting heart rate in relation to disease-specific mortality in London: 40 years follow-up of the original Whitehall study. An update of our work with Professor Jerry N. Morris (1910–2009) Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behrens G, Matthews CE, Moore SC. The association between frequency of vigorous physical activity and hepatobiliary cancers in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9767-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyle T, Bull F, Fritschi L, Heyworth J. Resistance training and the risk of colon and rectal cancers. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1091–1097. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9978-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyle T, Fritschi L, Heyworth J, Bull F. Long-term sedentary work and the risk of subsite-specific colorectal cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1183–1191. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyle T, Heyworth J, Bull F, McKerracher S, Platell C, Fritschi L. Timing and intensity of recreational physical activity and the risk of subsite-specific colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:1647–1658. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9841-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bravi F, Polesel J, Garavello W. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research recommendations and head and neck cancers risk. Oral Oncol. 2017;64:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenner DR, Wozniak MB, Feyt C. Physical activity and risk of pancreatic cancer in a central European multicenter case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:669–681. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0370-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calton BA, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Moore SC. A prospective study of physical activity and the risk of pancreatic cancer among women (United States) BMC Cancer. 2008;8:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eaglehouse YL, Koh WP, Wang R, Aizhen J, Yuan JM, Butler LM. Physical activity, sedentary time, and risk of colorectal cancer: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2017;26:469–475. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Etemadi A, Golozar A, Kamangar F. Large body size and sedentary lifestyle during childhood and early adulthood and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a high-risk population. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1593–1600. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Golshiri P, Rasooli S, Emami M, Najimi A. Effects of physical activity on risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study. Int J Prev Med. 2016;7:32. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.175991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunathilake MN, Lee J, Cho YA. Interaction between physical activity, PITX1 rs647161 genetic polymorphism and colorectal cancer risk in a Korean population: a case-control study. Oncotarget. 2018;9:7590–7603. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunathilake MN, Lee J, Jang A, Choi IJ, Kim YI, Kim J. Physical activity and gastric cancer risk in patients with and without helicobacter pylori infection in a Korean population: a hospital-based case-control study. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10:e369. doi: 10.3390/cancers10100369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hang J, Cai B, Xue P. The joint effects of lifestyle factors and comorbidities on the risk of colorectal cancer: a large Chinese retrospective case-control study. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heinen MM, Verhage BAJ, Goldbohm RA, Lumey LH, van den Brandt PA. Physical activity, energy restriction, and the risk of pancreatic cancer: prospective study in the Netherlands. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1314–1323. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.007542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hermann S, Rohrmann S, Linseisen J. Lifestyle factors, obesity and the risk of colorectal adenomas in EPIC-Heidelberg. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1397–1408. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hilal J, El-Serag HB, Ramsey D, Ngyuen T, Kramer JR. Physical activity and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:248–254. doi: 10.1111/dote.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Howard RA, Freedman DM, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A, Leitzmann MF. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and the risk of colon and rectal cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:939–953. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9159-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huerta JM, Chirlaque MD, Molina AJ. Physical activity domains and risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in the MCC-Spain case-control study. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huerta JM, Navarro C, Chirlaque MD. Prospective study of physical activity and risk of primary adenocarcinomas of the oesophagus and stomach in the EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and nutrition) cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:657–669. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ibáñez-Sanz G, Díez-Villanueva A, Alonso MH. Risk model for colorectal cancer in Spanish population using environmental and genetic factors: results from the MCC-Spain study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43263. doi: 10.1038/srep43263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inoue M, Yamamoto S, Kurahashi N, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane S. Daily total physical activity level and total cancer risk in men and women: results from a large-scale population-based cohort study in Japan. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:391–403. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiao L, Mitrou PN, Reedy J. A combined healthy lifestyle score and risk of pancreatic cancer in a large cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:764–770. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leitzmann MF, Koebnick C, Freedman ND. Physical activity and esophageal and gastric carcinoma in a large prospective study. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leitzmann MF, Koebnick C, Freedman ND. Physical activity and head and neck cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:1391–1399. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mok Y, Jeon C, Lee GJ, Jee SH. Physical activity level and colorectal cancer mortality. Asia Pac J Pub Health. 2016;28:638–647. doi: 10.1177/1010539516661761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Lochhead P. Prospective analysis of body mass index, physical activity, and colorectal cancer risk associated with β-catenin (CTNNB1) status. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1600–1610. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morrison DS, Batty GD, Kivimaki M, Davey Smith G, Marmot M, Shipley M. Risk factors for colonic and rectal cancer mortality: evidence from 40 years' follow-up in the Whitehall I study. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2011;65:1053–1058. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.127555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakamura K, Nagata C, Wada K. Cigarette smoking and other lifestyle factors in relation to the risk of pancreatic cancer death: a prospective cohort study in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:225–231. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nicolotti N, Chuang SC, Cadoni G. Recreational physical activity and risk of head and neck cancer: a pooled analysis within the international head and neck cancer epidemiology (INHANCE) Consortium. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26:619–628. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nilsen TIL, Romundstad PR, Petersen H, Gunnell D, Vatten LJ. Recreational physical activity and cancer risk in subsites of the colon (the Nord-Trøndelag health study) Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:183–188. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nomura SJO, Dash C, Rosenberg L, Yu J, Palmer JR, Adams-Campbell LL. Is adherence to diet, physical activity, and body weight cancer prevention recommendations associated with colorectal cancer incidence in African American women? Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:869–879. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0760-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nunez C, Nair-Shalliker V, Egger S, Sitas F, Bauman A. Physical activity, obesity and sedentary behaviour and the risks of colon and rectal cancers in the 45 and up study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:325. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parent ME, Rousseau MC, El-Zein M, Latreille B, Désy M, Siemiatycki J. Occupational and recreational physical activity during adult life and the risk of cancer among men. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sjödahl K, Jia C, Vatten L, Nilsen T, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Body mass and physical activity and risk of gastric cancer in a population-based cohort study in Norway. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:135–140. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tayyem RF, Shehadeh IN, Abumweis SS. Physical inactivity, water intake and constipation as risk factors for colorectal cancer among adults in Jordan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5207–5212. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.9.5207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turati F, Bravi F, Di Maso M. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research recommendations and colorectal cancer risk. Eur J Cancer. 2017;85:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolin KY, Patel AV, Campbell PT. Change in physical activity and colon cancer incidence and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2010;19:3000–3004. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu L, Zheng W, Xiang YB. Physical activity and pancreatic cancer risk among urban Chinese: results from two prospective cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2018;27:479–487. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yun YH, Lim MK, Won YJ. Dietary preference, physical activity, and cancer risk in men: national health insurance corporation study. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:366. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang J, Dhakal IB, Gross MD. Physical activity, diet, and pancreatic cancer: a population-based, case-control study in Minnesota. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:457–465. doi: 10.1080/01635580902718941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Page MJ, Moher D. Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement and extensions: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:263. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0663-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Duval S, Tweedie R. A nonparametric “Trim and Fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Denlinger CS, Sanft T, Baker KS. Survivorship, version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1216–1247. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Newton RU, Taaffe DR, Galvao DA. Clinical Oncology Society of Australia position statement on exercise in cancer care. Med J Aust. 2019;210:54. doi: 10.5694/mja2.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Buchner DM. The development and content of the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. J Phys Educ Recreat Dance. 2014;85:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:2375–2390. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kyu HH, Bachman VF, Alexander LT. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. BMJ. 2016;354:i3857. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mahmood S, MacInnis RJ, English DR, Karahalios A, Lynch BM. Domain-specific physical activity and sedentary behaviour in relation to colon and rectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1797–1813. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shaw E, Farris MS, Stone CR. Effects of physical activity on colorectal cancer risk among family history and body mass index subgroups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:71. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3970-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Psaltopoulou T, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Tzanninis IG, Kantzanou M, Georgiadou D, Sergentanis TN. Physical activity and gastric cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Sport Med. 2016;26:445–464. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nieman DC, Wentz LM. The compelling link between physical activity and the body's defense system. J Sport Health Sci. 2019;8:201–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu S, Fisher-Hoch SP, Reninger B, McCormick JB. Meeting or exceeding physical activity guidelines is associated with reduced risk for cancer in Mexican-Americans. Am J Cancer Prev. 2016;4:1–7. doi: 10.12691/ajcp-4-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu Y, Hu F, Li DD. Does physical activity reduce the risk of prostate cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2011;60:1029–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lim JW, Paek MS, Shon EJ. Gender and role differences in couples'communication during cancer survivorship. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:E51–E60. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mandal P. Molecular signature of nitric oxide on major cancer hallmarks of colorectal carcinoma. Inflammopharmacology. 2018;26:331–336. doi: 10.1007/s10787-017-0435-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Campbell KL, McTiernan A. Exercise and biomarkers for cancer prevention studies. J Nutr. 2007;137(Suppl. 1):S161–S169. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.161S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Friedenreich CM, Orenstein MR. Physical activity and cancer prevention: etiologic evidence and biological mechanisms. J Nutr. 2002;132(Suppl. 11):S3456–S3464. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3456S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Rimm EB. Prospective sstudy of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:451–459. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dong J, Dai J, Zhang M, Hu Z, Shen H. Potentially functional COX-2-1195G>A polymorphism increases the risk of digestive-system cancers: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1042–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee YY, Yang YP, Huang PI. Exercise suppresses COX-2 pro-inflammatory pathway in vestibular migraine. Brain Res Bull. 2015;116:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhao F, Cao Y, Zhu H, Huang M, Yi C, Huang Y. The-765G>C polymorphism in the cyclooxygenase-2 gene and digestive-system cancer: a meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8301–8310. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.19.8301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Inoue-Choi M, Hartge P, Liao LM, Caporaso N, Freedman ND. Association between long-term low-intensity cigarette smoking and incidence of smoking-related cancer in the national institutes of health-AARP cohort. Int J Cancer. 2018;142:271–280. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Klarich DS, Brasser SM, Hong MY. Moderate alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer risk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:1280–1291. doi: 10.1111/acer.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang YT, Gou YW, Jin WW, Xiao M, Fang HY. Association between alcohol intake and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:212. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2241-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang XZ, He QJ, Cheng TT. Predictive value of LINC01133 for unfavorable prognosis was impacted by alcohol in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;48:251–262. doi: 10.1159/000491724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Song Y, Liu M, Yang FG, Cui LH, Lu XY, Chen C. Dietary fibre and the risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:3747–3752. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.9.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vahid F, Shivappa N, Faghfoori Z. Validation of a dietary inflammatory index (DII) and association with risk of gastric cancer: a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:1471–1477. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.6.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yan B, Zhang L, Shao Z. Consumption of processed and pickled food and esophageal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull Cancer. 2018;105:992–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.bulcan.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Khalaf N, Yuan C, Hamada T. Regular use of aspirin or non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is not associated with risk of incident pancreatic cancer in two large cohort studies. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1380–1390. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Larsson SC, Giovannucci E, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15:2561–2564. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tan XL, Reid Lombardo KM, Bamlet WR. Aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and pancreatic cancer risk: a clinic-based case-control study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1835–1841. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.