Abstract

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common primary malignant tumor of bone. It is a common phenomenon that osteosarcoma cells have a hypoxic microenvironment. Hypoxia can dedifferentiate cells of several malignant tumor types into stem cell-like phenotypes. However, the role of hypoxia in stemness induction and the expression of cancer stem cell (CSC) markers in human osteosarcoma cells has not been reported. The present study examined the effects of hypoxia on stem-like cells in the human osteosarcoma MNNG/HOS cells. Under the incubation with 1% oxygen, the expression of CSCs markers (Oct-4, Nanog and CD133) in MNNG/HOS cells were increased. Moreover, MNNG/HOS cells cultured under hypoxic conditions were more likely to proliferate into spheres and resulted in larger xenograft tumor. Hypoxia also increased the mRNA and protein levels of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α. Then rapamycin was used, which has been shown to lower HIF-1α protein level, to inhibit the hypoxic response. Rapamycin suppressed the expression of HIF-1α protein and CSCs markers (Oct4, Nanog and CD133) in MNNG/HOS cells. In addition, pretreatment with rapamycin reduced the efficiency of MNNG/HOS cells in forming spheres and xenograft tumors. The results demonstrated that hypoxia (1% oxygen) can dedifferentiate some of the MNNG/HOS cells into stem cell-like phenotypes, and that the mTOR signaling pathway participates in this process via regulating the expression of HIF-1α protein.

Keywords: osteosarcoma cells, mTOR, hypoxia, cancer stem cells

Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common primary malignant tumor of bone and is frequently diagnosed in children and young adults (1). Osteosarcoma is also the most frequent cause of bone cancer-associated death in children and adolescents (2). Osteosarcoma mainly arises from the metaphysis of long bones, with a predilection for the distal end of the femur and the proximal end of the humerus (3). Common causes of death for patients with osteosarcoma include tumor recurrence and metastasis (4). Therefore, it is of clinical importance to resolve the molecular mechanisms underlying the occurrence and development of osteosarcoma to improve treatment strategies.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are defined as a distinct subpopulation of tumor cells that possess stem cell characteristics, including unlimited self-renewal, tumor-initiating potential and pluripotent differentiation abilities (5). Several studies haves shown that CSCs are responsible for cancer recurrence (6,7). CSCs are similar to normal stem cells, and their differentiation is influenced by numerous factors, such as genetics and the environment (8). Researchers have shown that an increase in the stemness of cancer cells is associated with hypoxia (9). A previous study showed that poorly differentiated cancer cells or CSC-like tumor cells are located in the hypoxic region of neuroblastoma (10). In addition, poorly differentiated pancreatic cancer cells have a significantly increased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α protein in the nucleus (11). Higher levels of HIF-1α protein are observed in the stem cell-like tumor cells in gliomas (12). Studies have also suggested that hypoxia can affect the differentiation of tumor cells and increase the expression of stem cell markers in tumor cells (9–13). It has been demonstrated that hypoxia can activate the mTOR pathway, and the increased expression of HIF-1α may also be related to the activation of the mTOR pathway (14). Hypoxia increases the expression of stem cell markers in brain tumor cells (9). However, it remains unclear whether the fate of human osteosarcoma cells is regulated by hypoxia. Does hypoxia enhance the expression of stem cell markers in human osteosarcoma cells? Is this associated with the mTOR signaling pathway?

The present study was divided into two parts: In vitro and in vivo. Firstly, in vitro, human osteosarcoma cells were cultured under hypoxic conditions, and then changes in the expression of CSCs markers were investigated. Secondly, in vivo, human osteosarcoma cells were cultured under hypoxic and normoxic conditions and subcutaneously injected into nude mice to compare their tumorigenic ability. Finally, rapamycin was used to block the effects of hypoxia in osteosarcoma cells to explore the involvement of the mTOR signaling pathway in the gain of the CSCs phenotype. The aim of the present study was to determined if hypoxia enhanced the expression of stem cell markers in human osteosarcoma cells, and to investigate if this was related to the mTOR signaling pathway.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

The human osteosarcoma cell line MNNG/HOS was purchased from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences. The cells were cultured in essential medium MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (both HyClone; Cyvita) and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin in vitro. The cells were cultured at 37°C under normoxic conditions (5% CO2, 95% air).

Tumor sphere culture

MNNG/HOS cells were plated at a density of 1×105 cells/well in ultra-low-attachment 6-well plates (Corning Life Sciences) in MEM cell medium, supplemented with EGF (20 ng/ml), basic fibroblast growth factor (20 ng/ml), Noggin (10 ng/ml) and leukemia inhibitory factor (1,000 U/ml). The cells were divided into three groups: Hypoxia, rapamycin and control. Cells in the control group were cultivated in an incubator at 37°C under normoxic conditions (5% CO2, 95% air). Cells in the hypoxia and rapamycin groups were cultivated in an incubator at 37°C under hypoxia (1% O2, 5% CO2 and 94% nitrogen). Cells in rapamycin group were pretreated with rapamycin (100 nmol/l) for 30 min before hypoxia culture, with the remaining culture conditions the same as those of hypoxia group. After 3 days of culture, spheres were observed and images were captured using an inverted phase contrast microscope (Eclipse TS100/100-F; Nikon Corporation), and those with a diameter >100 µm were counted. The experiments were repeated at least three times.

Flow cytometry

To measure the proportion of CD133+ cells in single cell suspension of MNNG/HOS cells from the three groups cultured under different conditions, cells were digested with trypsin (Sigma-Alrdich; Merck KGaA), centrifuged at room temperature for 5 min at 200 × g, collected and washed twice with PBS. Cells were then incubated with CD133-FITC (1:100; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.) at 4°C for 60 min in the dark, followed by washing twice with combining buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Finally, the labeled cells were analyzed NAVIOS flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA of MNNG/HOS cells from the three groups was extracted using TRIzol® reagent and treated with DNase I (both Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The purity of the extracted RNA was determined by the absorbance ratio at 260/280 on the Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Then, RNA was reverse transcribed using the 5X All-In-One RT MasterMix (G492, Applied Biological Materials Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT-qPCR was performed on a Light Cycler 480 system (Roche Diagnostics) using the SYBER GreenERTM qPCR SuperMix (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the following parameters: Pre-incubation at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles amplification at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The relative expression level of the genes was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (15). The primers used were: Oct-4, Forward: 5′-CTGAGGTGCCTGCCCTTCTA-3′ and reverse: 5′-CCAACCAGTTGCCCCAAAC-3′; Nanog, forward: 5′-ACCTATGCCTGTGATTTGTGGG-3′ and reverse: 5′-AGAAGTGGGTTGTTTGCCTTTG-3′; GAPDH, forward: 5′-ATGACATCAAGAAGGTGGTG-3′ and reverse: 5′-CATACCAGGAAATGAGCTTG-3′. Gene (mRNA) expression levels of Oct-4 and Nanog were normalized to that of GAPDH transcript. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

In vivo xenograft experiments

In total, 15 5–6-week old (body weight 20±2 g) male BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Company. The mice were kept in laminar-flow cabinets under specific pathogen-free conditions and inspected every day. The light dark cycle was 10 h/14 h. The mice drink water freely. The mice were given free access to laboratory chow. The nude mice were randomized into three groups (n=5 for each group). MNNG/HOS cells were cultured under different conditions of hypoxia, rapamycin and control groups as aforementioned, and then subcutaneously (right shoulder blade) injected into nude mice (1×106 cells per mouse). The size of the xenograft tumors was monitored once a week after tumor inoculation. The tumor volume (V) was calculated using the following formula: V (mm3) = 0.5 ab2. The largest (a) and the smallest (b) superficial diameters of the tumor were measured with a vernier caliper. The mice were sacrificed 49 days after injection of tumor cells, and the tumors were excised and weighed. All experiments were approved by The Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University (Fuzhou, China). None of the mice died during the experimental process.

Western blotting

Whole-cell extracts were obtained using pre-chilled RIPA [10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1.0% Triton X-100, 1.0% Na deoxycholate and 5 mM EDTA] containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Then, the protein concentration of the supernatants was determined. Determination of protein concentration was performed with the Easy II Protein Quantitative kit (BCA; Beijing Transgen Biotech Co., Ltd.) in accordance to the manufacturer's protocol. The total proteins were loaded and electrophoresed in 10% SDS-PAGE gel and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane (EMD Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST buffer [10 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mmol/l NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20], and then were incubated overnight with primary antibodies diluted in TBST at 4°C and subsequently with horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (1:1,000; cat. no. A0208; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies included: Oct-4 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab181557; Abcam), Nanog (1:1,000; cat. no. ab109250; Abcam), β-actin (1:1,000; cat. no. ab8227; Abcam), phosphorylated (p-)mTOR (1:1,000; cat. no. ab84400; Abcam), mTOR (1:1,000; cat. no. ab32028; Abcam), p-P70S6K (1:1,000; cat. no. AF5899; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), P70S6K (1:1,000; cat. no. AF0258; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and HIF-1α (1:1,000; cat. no. AF7087; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and images were captured using a Kodak X-OMAT 2000A film processor. The protein was analyzed by Image J software (version 1.52, National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp) and GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software). The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test was used to determine the statistical significance. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

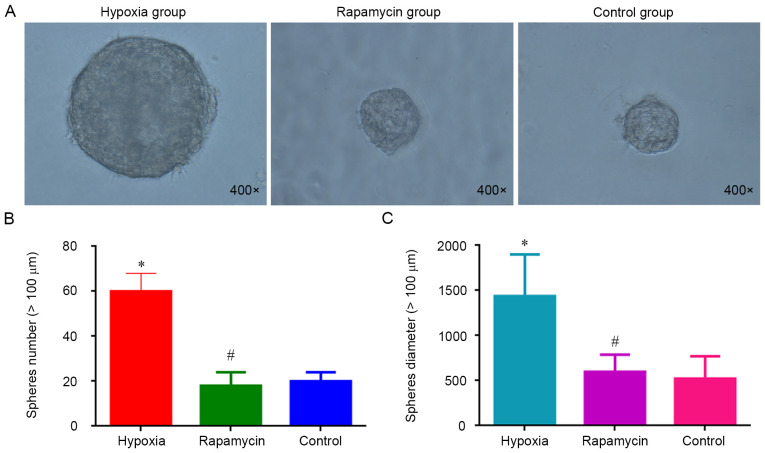

Hypoxia increases the sphere formation of MNNG/HOS cells

Sphere formation is considered a hallmark of CSCs (16). To evaluate the effect of hypoxia on the sphere formation, MNNG/HOS cells were cultured in ultra-low-attachment plates with stem cell-specific medium under hypoxia. It was observed that the cells cultured in hypoxia group were significantly more efficient in forming spheres compared with the control group (P<0.05). However, there was no difference regarding the sphere formation ability between the rapamycin and control groups (Fig. 1). Hypoxia increases the sphere formation of MNNG/HOS cells and rapamycin can inhibit this process.

Figure 1.

Sphere clusters formed by MNNG/HOS cells. (A) Sphere clusters formed by MNNG/HOS cells after 3-day culture in ultra-low-attachment 6-well plates under different conditions (magnification, ×400). (B) Number of spheres (diameter >100 µm) after 3-day culture. (C) Diameter of the spheres (>100 µm) after 3-day culture. *P<0.05 and #P>0.05 vs. control group.

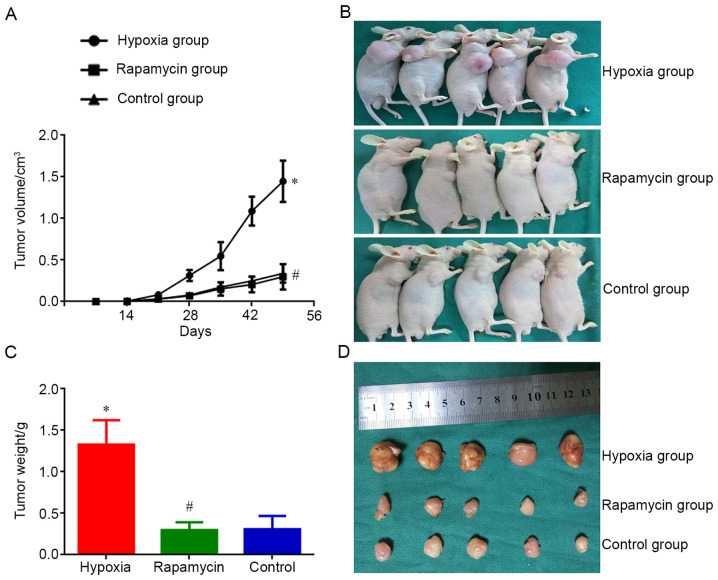

Hypoxia enhances the ability of MNNG/HOS cells to form xenograft tumors in vivo

MNNG/HOS cells cultured in each group were injected into nude mice. Tumors appeared 14 days after the injection. On day 14 after injection, the size of MNNG/HOS xenograft tumors in the hypoxia group was significantly bigger compared with that in the control group (P<0.05). However, the tumor size of mice in the rapamycin group was not different compared with that in the control group. On day 49 after injection, the size difference of xenograft tumors was significant between the hypoxia and control groups (P<0.05). There was also a significant difference in tumor weight between the two groups (P<0.05). Nevertheless, the difference regarding average volume and weight of xenograft tumors between rapamycin and control groups was not different on day 49 after injection (Fig. 2). Hypoxia enhanceed the ability of MNNG/HOS cells to form xenograft tumors in vivo and rapamycin can inhibit this process.

Figure 2.

Tumor proliferation of MNNG/HOS cells in vivo. (A) Tumor growth curve of MNNG/HOS cells injected subcutaneously into nude mice in different groups. (B) Size of xenografted tumors in different groups. (C) Resected tumor weight after sacrifice in different groups. (D) Resected tumor volume after sacrifice in different groups. *P<0.05 and #P>0.05 vs. control group.

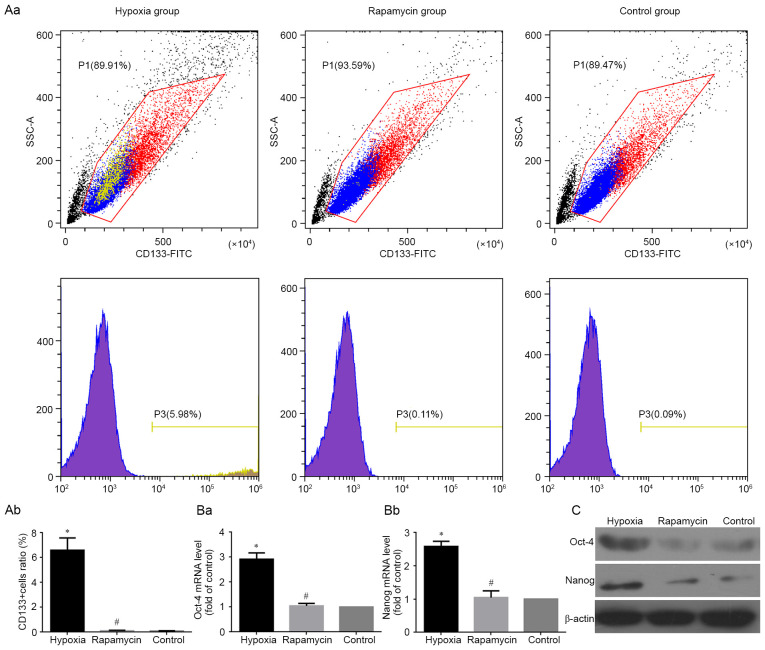

Hypoxia induces the expression of CSC markers

The stem genes Oct4, Nanog and CD133 have been identified as CSC markers in several types of tumors (17–19), including human osteosarcoma (19). Therefore, the present study detected mRNA and protein expression of Oct4 and Nanog using RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively, in MNNG/HOS cells under different conditions. The results clearly showed that the mRNA and protein levels of Oct4 and Nanog were significantly higher in hypoxic group compared with the control group (both P<0.05). However, there was no difference in the expression of Oct4 and Nanog between the rapamycin and control groups (Fig. 3Ba, Bb and C). At the same time, the percentage of CD133+ subgroup cells were detected using flow cytometry under different conditions. The results showed that the percentage of CD133+ subgroup cells was significantly increased in hypoxic group compared with the control group (P<0.05). However, the percentage difference of CD133+ cells between the rapamycin and control groups were not significant (Fig. 3Aa and Ab).

Figure 3.

Change of the expression of tumor stem cell markers. (A) CD133+ MNNG/HOS cells in different groups analyzed using flow cytometry analysis. (Aa) Representative images showing the expression ratio of CD133+ cells in different groups of MNNG/HOS cells. (Ab) Changes of the expression level of CD133+ cells in different groups of MNNG/HOS cells. (B) mRNA levels of (Ba) OCT4 and (Bb) Nanog in different groups analyzed using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis. Data are normalized to GAPDH and represented as relative expression (relative to control). (C) Expression of OCT4, Nanog and CD133 protein in MNNG/HOS cells cultured in different groups analyzed using western blotting. β-actin was used as an internal control. *P<0.05 and #P>0.05 vs. control group.

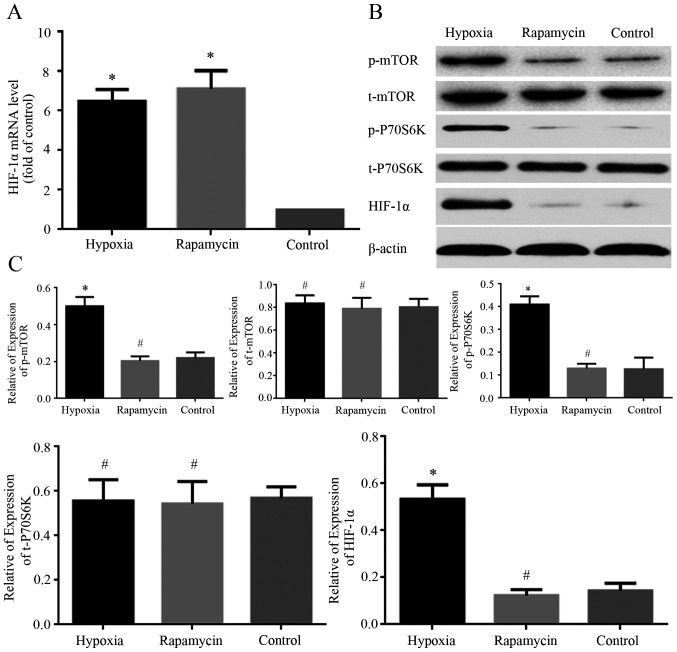

HIF-1α is involved in the effects of hypoxia on MNNG/HOS cells

The expression levels of HIF-1α mRNA and protein in MNNG/HOS cells cultured under different conditions were examined using RT-qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. The mRNA level of HIF-1α was markedly increased in hypoxia and rapamycin groups compared with control group (Fig. 4A). The protein expression of HIF-1α was markedly increased in hypoxia group compared with control group (Fig. 4B and C). However, there was no significant difference in the protein expression of HIF-1α between the rapamycin and control groups (Fig. 4B and C). Hypoxia increased the level of HIF-1α protein expressed by MNNG/HOS cells, and rapamycin inhibited this process.

Figure 4.

Change of the expression of HIF-1α, p-P70S6K, t-P70S6K, p-mTOR, t-mTOR. (A) mRNA level of HIF-1α analyzed using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. All data are normalized to GAPDH and represented as relative expression (relative to control). (B) Representative images showing the expression of HIF-1α, p-mTOR, t-mTOR, p-P70S6K and t-P70S6K in MNNG/HOS cells in different groups. (C) Quantification of expression levels of HIF-1α, p-mTOR, t-mTOR, p-P70S6k and t-P70S6k in MNNG/HOS cells in different groups. β-actin was used as a loading control. *P<0.05 and #P>0.05 vs. control group. HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; p-, phosphorylated; t-, total.

To explore the mechanism of HIF-1α involvement in hypoxia-induced effects on MNNG/HOS cells, the expression levels of mTOR signaling proteins under different conditions were examined using western blotting. The phosphorylated levels of mTOR and P70S6K were markedly increased in the hypoxia group compared with control group. However, there was no significant difference in the phosphorylated expression of the two proteins between the rapamycin and control groups (Fig. 4B and C). Meanwhile, there was no difference in total protein expression of mTOR and P70S6K among the three groups (Fig. 4B and C). The phosphorylated levels of mTOR and P70S6K were markedly increased under hypoxia condition and rapamycin can inhibit this process.

Discussion

CSCs are a small group of cancer cells that have stem cell properties of self-renewal and differentiation (20). CSCs also play a crucial role in tumor initiation, progression and invasion of cancer (21). CSCs have been identified in several solid tumors, such as brain cancer (22), ovarian cancer (23) and leiomyosarcoma (24). Numerous types of malignant tumor cells dedifferentiate into stem-like cell phenotypes under hypoxia (25–27). However, it remains unclear whether the human osteosarcoma cells can dedifferentiate into stem-like cells under hypoxia. The present data reported that hypoxia induced the stemness transformation of human osteosarcoma cells as demonstrated by increased expression of stem cell markers, promoting the formation of spheres and xenograft tumorigenesis. The mTOR signaling pathway was also involved in the transformation process via regulating activation of the HIF-1α protein.

Studies have shown that hypoxia can increase the expression of stem cell markers in several malignant cell types, such as glioblastoma (28), breast cancer (29) and neuroblastoma (25). Hypoxia, a common feature of several solid tumors, including osteosarcoma, is associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis (30–32). In the present study, hypoxia led to increased expression of stem cell markers, including Oct4, Nanog and CD133, in MNNG/HOS cells. Moreover, hypoxia promoted the formation of spheres and xenograft tumorigenesis of MNNG/HOS cells. These results suggested that hypoxia can dedifferentiate MNNG/HOS cells into stem cell-like phenotypes, which may explain the contributing role of hypoxia to these malignant properties.

Transcriptional response to hypoxia is commonly regulated by HIFs (33). HIFs are composed of two subunits, HIF-α and HIF-β (34). HIF-1α is the regulatory subunit of HIF-1, a crucial mediator of the cellular response to hypoxia (35). Therefore, HIF-1α is a key regulator for hypoxia tolerance of osteosarcoma (36). The present study observed an increased level of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions in MNNG/HOS cells. Rapamycin can reduce HIF-1α protein expression through promoting HIF-1α protein degradation (37). The present research also showed that hypoxia-induced dedifferentiation of MNNG/HOS cells into stem cell phenotypes could be inhibited rapamycin. This suggested that HIF-1α plays an important role in the dedifferentiation of human osteosarcoma cells into stem cell-like cells.

P70S6K1 is one of the most important effectors downstream of the mTOR pathway. mTOR can phosphorylate P70S6K to phosphorylate 40S ribosomal protein s6 in cells, thereby regulating the transcription and translation of mRNA and protein synthesis (38). Studies have shown that hypoxia can activate the mTOR pathway, and the increased expression of HIF-1 may also be related to the activation of the mTOR pathway (14). In the present experiment, under hypoxic conditions, the increased expression of p-mTOR and p-P70S6K was expected. The present study showed that the activation of mTOR pathway under hypoxic conditions was associated with the expression levels of CSCs markers in osteosarcoma cells and the formation of spheres and xenograft tumors.

Rapamycin can inhibit the activation effect of mTOR signaling pathway caused by hypoxia, and reduce the expression levels of mTOR pathway-related proteins (39). Rapamycin was one of the first mTOR inhibitors used to inhibit the entire pathway (40). Rapamycin was used in the present study to further verify the activation effect of mTOR signaling pathway in osteosarcoma cells under hypoxia and its role in the expression levels of CSCs markers and the formation of spheroid and xenograft tumors. Under the action of rapamycin, the expression of p-mTOR and p-P70S6K in osteosarcoma cells of the rapamycin group were significantly reduced, and the mTOR signaling pathway was inhibited, indicating that the effect of rapamycin was as expected. Compared with the hypoxia group, osteosarcoma cells treated with rapamycin had lower expression levels of CSCs markers, and inhibited spheroid formation and xenograft tumor formation. These results indicated that inhibition or deactivation of the mTOR signaling pathway can affect osteosarcoma cell differentiation into a stem cell-like phenotype.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that hypoxia induced stemness transformation of human osteosarcoma cells, promoting the formation of spheres and xenograft tumor. HIF-1α activated by mTOR signaling was involved in this process and could be a therapeutic target to inhibit the malignant transformation of osteosarcoma cells.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Guangxian Zhong (Orthopaedic Research Institute, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China) for providing technical assistance and useful discussions.

Funding

The present study was supported by The Scientific Research Project for Fujian Provincial Health and Youth Health Research Project (grant no. 2019-1-45), The Startup Fund for Scientific Research, Fujian Medical University (grant no. 2018QH1055) and The Nature Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (grant no. 2017J01278).

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JLL, XinwuW and XinwenW conducted the experiments and drafted the manuscript. SLW and RKS contributed to statistical analysis and manuscript writing. YBY and JYX participated in performing the cell experiments. JHL conceived the present study and helped revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Huang CY, Wei PL, Wang JW, Makondi PT, Huang MT, Chen HA, Chang YJ. Glucose-regulated protein 94 modulates the response of osteosarcoma to chemotherapy. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:4569718. doi: 10.1155/2019/4569718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urciuoli E, Giorda E, Scarsella M, Petrini S, Peruzzi B. Osteosarcoma-derived extracellular vesicles induce a tumor-like phenotype in normal recipient cells. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:6158–6172. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Zeng C, Tu M, Jiang W, Dai Z, Hu Y, Deng Z, Xiao W. MicroRNA-200b acts as a tumor suppressor in osteosarcoma via targeting ZEB1. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:3101–3111. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S96561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 4.Zhang Z, Luo G, Yu C, Yu G, Jiang R, Shi X. MicroRNA-493-5p inhibits proliferation and metastasis of osteosarcoma cells by targeting Kruppel-like factor 5. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:13525–13533. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrò C, Moch H. Biomarker discovery for renal cancer stem cells. J Pathol Clin Res. 2018;4:3–18. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wahab SMR, Islam F, Gopalan V, Lam AK. The identifications and clinical implications of cancer stem cells in colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi M, Li J, Chen S, Cai J, Ban Y, Peng Q, Zhou Y, Zeng Z, Peng S, Li X, Xiong W, Li G, Xiang B. Correction to: Emerging role of lipid metabolism alterations in Cancer stem cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:155. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0826-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang P, Zhang Y, Zhu C, Zhang W, Mao Z, Gao C. Fe3O4/BSA particles induce osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells under static magnetic field. Acta Biomater. 2016;46:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad P, Mittal SA, Chongtham J, Mohanty S, Srivastava T. Hypoxia-mediated epigenetic regulation of stemness in brain tumor cells. Stem Cells. 2017;35:1468–1478. doi: 10.1002/stem.2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Q, Yun Z. Impact of the hypoxic tumor microenvironment on the regulation of cancer stem cell characteristics. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:949–956. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.12.12347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couvelard A, O'Toole D, Turley H, Leek R, Sauvanet A, Degott C, Ruszniewski P, Belghiti J, Harris AL, Gatter K, Pezzella F. Microvascular density and hypoxia-inducible factor pathway in pancreatic endocrine tumours: negative correlation of microvascular density and VEGF expression with tumour progression. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:94–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Z, Bao S, Wu Q, Wang H, Eyler C, Sathornsumetee S, Shi Q, Cao Y, Lathia J, McLendon RE, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y, Lin Q, Glazer PM, Yun Z. Hypoxic tumor microenvironment and cancer cell differentiation. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:425–434. doi: 10.2174/156652409788167113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan G, Nanduri J, Khan S, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Induction of HIF-1alpha expression by intermittent hypoxia: Involvement of NADPH oxidase, Ca2+ signaling, prolyl hydroxylases, and mTOR. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:674–685. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin X, Sun B, Zhu D, Zhao X, Sun R, Zhang Y, Zhang D, Dong X, Gu Q, Li Y, et al. Notch4+ cancer stem-like cells promote the metastatic and invasive ability of melanoma. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:1079–1091. doi: 10.1111/cas.12978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan Z, Li M, Chen X, Wang J, Liang X, Wang H, Wang Z, Cheng B, Xia J. Prognostic value of cancer stem cell markers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43008. doi: 10.1038/srep43008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradshaw A, Wickremsekera A, Tan ST, Peng L, Davis PF, Itinteang T. Cancer stem cell hierarchy in glioblastoma multiforme. Front Surg. 2016;3:21. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Park P, Zhang H, La Marca F, Lin CY. Prospective identification of tumorigenic osteosarcoma cancer stem cells in OS99-1 cells based on high aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:294–303. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y, Zhao W, Lim YC, Liu T. Salinomycin-loaded gold nanoparticles for treating cancer stem cells by ferroptosis-induced cell death. Mol Pharm. 2019;16:2532–2539. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng L, Cen Y, Chen J. Long non-coding RNA MALAT-1 contributes to maintenance of stem cell-like phenotypes in breast cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:2117–2122. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.Mukherjee S, Baidoo JNE, Sampat S, Mancuso A, David L, Cohen LS, Zhou S, Banerjee P. Liposomal TriCurin, a synergistic combination of curcumin, epicatechin gallate and resveratrol, repolarizes tumor-associated microglia/macrophages, and eliminates glioblastoma (GBM) and GBM stem cells. Molecules. 2018;23:201. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnapriya S, Sidhanth C, Manasa P, Sneha S, Bindhya S, Nagare RP, Ramachandran B, Vishwanathan P, Murhekar K, Shirley S, et al. Cancer stem cells contribute to angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Angiogenesis. 2019;22:441–455. doi: 10.1007/s10456-019-09669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fourneaux B, Bourdon A, Dadone B, Lucchesi C, Daigle SR, Richard E, Laroche-Clary A, Le Loarer F, Italiano A. Identifying and targeting cancer stem cells in leiomyosarcoma: Prognostic impact and role to overcome secondary resistance to PI3K/mTOR inhibition. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:11. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0694-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohlin S, Wigerup C, Jögi A, Påhlman S. Hypoxia, pseudohypoxia and cellular differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2017;356:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang P, Lan C, Xiong S, Zhao X, Shan Y, Hu R, Wan W, Yu S, Liao B, Li G, et al. HIF1α regulates single differentiated glioma cell dedifferentiation to stem-like cell phenotypes with high tumorigenic potential under hypoxia. Oncotarget. 2017;8:28074–28092. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maeda K, Ding Q, Yoshimitsu M, Kuwahata T, Miyazaki Y, Tsukasa K, Hayashi T, Shinchi H, Natsugoe S, Takao S. CD133 modulate HIF-1α expression under hypoxia in EMT phenotype pancreatic cancer stem-like cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1025. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bar EE, Lin A, Mahairaki V, Matsui W, Eberhart CG. Hypoxia increases the expression of stem-cell markers and promotes clonogenicity in glioblastoma neurospheres. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1491–1502. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conley SJ, Gheordunescu E, Kakarala P, Newman B, Korkaya H, Heath AN, Clouthier SG, Wicha MS. Antiangiogenic agents increase breast cancer stem cells via the generation of tumor hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2784–2789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018866109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Q, Lan F, Yan X, Xiao Z, Wu Y, Zhang Q. Hypoxia exposure induced cisplatin resistance partially via activating p53 and hypoxia inducible factor-1α in non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:801–808. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang ZL, Tian W, Wang Q, Zhao Y, Zhang YL, Tian Y, Tang YX, Wang SJ, Liu Y, Ni QQ, et al. Oxygen-evolving mesoporous organosilica coated prussian blue nanoplatform for highly efficient photodynamic therapy of tumors. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2018;5:1700847. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao H, Wu Y, Chen Y, Liu H. Clinical significance of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and VEGF-A in osteosarcoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:1233–1243. doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0848-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manresa MC, Taylor CT. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) hydroxylases as regulators of intestinal epithelial barrier function. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorga A, Rindone G, Regueira M, Riera MF, Pellizzari EH, Cigorraga SB, Meroni SB, Galardo MN. HIF involvement in the regulation of rat Sertoli cell proliferation by FSH. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;502:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bao L, Chen Y, Lai HT, Wu SY, Wang JE, Hatanpaa KJ, Raisanen JM, Fontenot M, Lega B, Chiang CM, et al. Methylation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α by G9a/GLP inhibits HIF-1 transcriptional activity and cell migration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:6576–6591. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo M, Cai C, Zhao G, Qiu X, Zhao H, Ma Q, Tian L, Li X, Hu Y, Liao B, et al. Hypoxia promotes migration and induces CXCR4 expression via HIF-1α activation in human osteosarcoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dodd KM, Yang J, Shen MH, Sampson JR, Tee AR, KM D. mTORC1 drives HIF-1α and VEGF-A signalling via multiple mechanisms involving 4E-BP1, S6K1 and STAT3. Oncogene. 2015;34:2239–2250. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornu M, Albert V, Hall MN, M C. mTOR in aging, metabolism, and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verheul HM, Salumbides B, Van Erp K, Hammers H, Qian DZ, Sanni T, Atadja P, Pili R. Combination strategy targeting the hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha with mammalian target of rapamycin and histone deacetylase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3589–3597. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou H, Miao J, Cao R, Han M, Sun Y, Liu X, Guo L. Rapamycin ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing the mTOR-STAT3 pathway. Neurochem Res. 2017;42:2831–2840. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.