Abstract

Background: There is an increasing interest in acupuncture for promoting post-operative rehabilitation, but the effectiveness of acupuncture for rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) remains controversial.

Objective: This study aims to investigate the effect of acupuncture on rehabilitation after TKA.

Methods: Database searches of PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) were conducted to obtain articles published until August 2020. All identified articles were screened, and data from each included study were extracted independently by two investigators. Meta-analysis was performed to examine the effects of acupuncture on pain, range of knee motion, function, and nausea/vomiting after TKA.

Results: A total of nine randomized clinical trials were included according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria in this review. Compared with routine treatment, acupuncture combined with routine treatment showed a significantly greater pain reduction at 8, 12, 24, and 48 h post-operatively after TKA. Meanwhile, we found that the acupuncture groups showed a significant function improvement and a lower percentage of nausea/vomiting in comparison with the control groups after operation. However, acupuncture groups demonstrated no statistically significant improvement in post-operative pain at 4 h, 7 days, 14 days, and more than 21 days, and no significant difference in range of knee motion was observed between the acupuncture groups and control groups after surgery.

Conclusions: Acupuncture, as a supplementary treatment after TKA, could improve function and reduce nausea/vomiting. However, the effect of acupuncture on pain relief may be mainly achieved within post-operative 48 h, and it had no efficacy in improving range of knee motion. More large-scale and high-quality studies are warranted.

Keywords: acupuncture, total knee arthroplasty, pain, function, systematic review

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) has become a major factor in disability for the elderly, which heavily compromises the quality of people's life (1). With the development of KOA, the destruction of articular cartilage will be deteriorated (2). For advanced KOA patients, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is one of the common surgeries (3), which leads to a high degree of patient satisfaction because of considerable medium- and long-term benefits, including improvement in quality of life, pain relief, and function recovery (4). Nevertheless, TKA is followed by some complications, such as post-operative pain, limited joint function, and analgesia-related adverse effects, which exert a great impact on post-operative rehabilitation (5). Therefore, it is very important to take measures to manage the complications after TKA surgery, especially to explore a method to reduce post-operative pain (6). Historically, pharmacological methods, including anesthetics, opioids, and acetaminophen, serve as the first-line therapies to treat post-operative pain (7). However, drug-related adverse effects limit their application in daily clinical practice. Thus, many non-pharmacological approaches have developed, including preoperative exercise (8), cryotherapy (9), electrotherapy (10), and acupuncture (11), in order to obtain a better pain management and reduce the use of prescription medications.

Acupuncture, a traditional Chinese therapeutic technique with more than 3,000-year history, has been widely used to treat pain of many origins (12). Regarding the analgesic mechanism of acupuncture, it was suggested that needle stimulation to small-diameter nerve fibers could activate central nervous system at spinal level and higher brain center, and subsequently endogenous opioids and neurotransmitters would be generated and released (13). A previous meta-analysis indicated that certain modes of acupuncture could improve post-operative pain on the first day after surgery and reduced opioid use, and acupuncture should be considered an adjuvant therapy in treating post-operative pain (14). As was reported in another meta-analysis (15) including four randomized controlled trials (RCT), acupuncture was associated with reduced and delayed opioid consumption after TKA. In recent years, increasing number of RCTs investigated the efficacy of acupuncture in post-surgical recovery for patients receiving TKA. Some evidence (16–23) demonstrated that acupuncture could provide positive effects on pain management, reduction of swelling around the knee, early recovery range of motion (ROM), and hiccups for patients after TKA. On the contrary, two studies (24, 25) found that there was no significant effect on rehabilitation for patients with TKA. Consequently, clinical data examining the effectiveness of acupuncture for pain reduction and function improvement after TKA were inconsistent. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture for rehabilitation after TKA.

Methods

Ethical approval was not required in this review because all the analyses were based on data published in previous studies. This meta-analysis was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (26).

Selection Criteria

In this study, the patients, interventions, comparators, and outcomes (PICO) question was taken into consideration at our primary search. All the included literatures should meet the following criteria: ① Study design: clinical randomized controlled study; ② Patients: patients undergoing primary TKA; ③ Intervention: acupuncture, including traditional acupuncture, needle, and dry needle; or acupuncture + other treatments; ④ Comparators: acupuncture vs. other treatments, acupuncture + other treatments vs. other treatments, acupuncture vs. placebo or sham acupuncture; ⑤ Outcomes: post-operative rehabilitation, at least one efficacy index; and ⑥ Languages: Chinese and English. Studies would be excluded if it met any of the following criteria: ① Conference abstracts, unpublished literatures, or full-text unavailable articles; ② Repeated publications, unicompartment knee arthroplasty, revision TKA, animal experimental studies, or reviews.

Search Strategy

We searched electronic databases to obtain relevant studies, including PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CINAHL), and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database, up to 29 August 2020. A search string such as “acupuncture,” “needle,” “total knee arthroplasty,” “total knee replacement,” “TKA,” “randomized controlled trial,” “controlled clinical trial,” “randomized,” “placebo,” “randomly,” and “trial,” etc. was used to search without restrictions. The search strategy is described in detail in Supplementary Figure 1. Two researchers (ZH Chen and JT Wu) performed preliminarily screening after careful reading of the title and abstracts. Subsequently, the remaining studies were screened strictly after reading the full text, and the eligible studies were included according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, the data and materials in the included literatures were extracted without controversy. During the period of screening and data extraction, if discrepancies could not be resolved through discussion, the primary reviewer would be consulted.

Data Extraction

The two investigators who screened the literatures independently extracted the main information from the included articles, including authors' names, publication year, age and gender of patients, study design, intervention type, acupuncture points, needle retaining time, intervention dose, main outcomes, and sample size.

Quality Assessment

According to version 5.1.0 (27) of the Cochrane manual, the quality of the included literatures was qualitatively assessed with the risk of bias table by two reviewers (ZH Chen and WJ Chen). The literature was evaluated from seven aspects: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blind of participants and personnel, blind of outcome, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. The risk of each item is divided into three levels: high, unclear, and low.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted the meta-system analysis of the observation indicators in the included literatures by using the review manager 5.3 software, and the results were illustrated by the forest map intuitively. The continuous variables were pooled by standard mean differences (SMDs) or mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), whereas the odds ratios (OR) were utilized to assess the enumeration data. Heterogeneity was assessed by the Cochran Q test and I2 index (28). An I2 statistic >50% was considered to be substantially heterogeneous. Based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (29), when the number of studies was <5 or studies are shown to be substantially heterogeneous, a random-effects model should be applied. Publication bias was assessed by the Begg's and Egger's tests. The difference was statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Study Selection

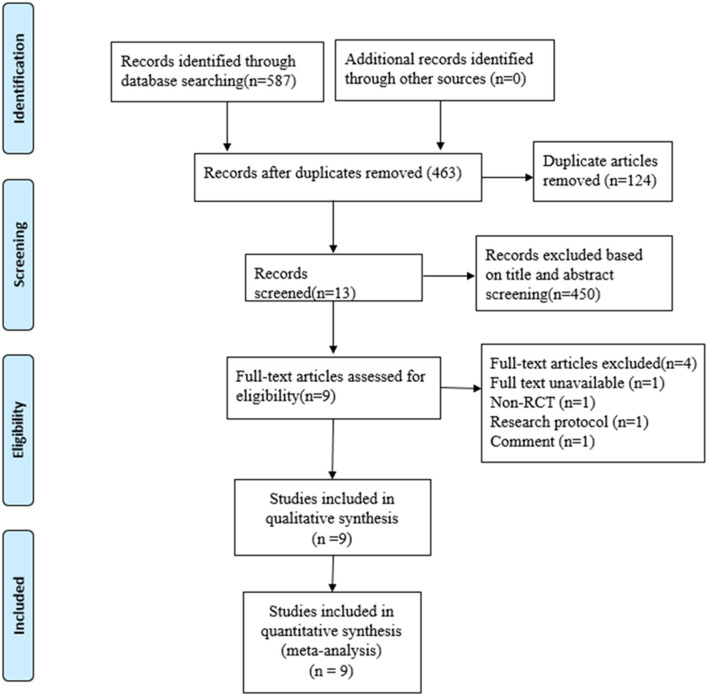

A total of 587 studies were yielded by searching Chinese and English databases. After removing 124 duplicates and eliminating 454 articles through the preliminary screening, reading summary, and full text, 9 RCTs (18–22, 24, 25) were selected and 671 TKA patients were included. Four studies were excluded: one conference abstract, one comment, one without full text, and one observational study (Supplementary Table 1). The flowchart for the selection process is shown in Figure 1, and the basic information of each included literature is shown in Table 1. In this review, two (20, 25) of the included studies reported sham acupuncture applied in the control group (CG), and no acupuncture was used in the CG among the remaining studies. In the study reported by Tsang et al. (20), sham acupuncture was conducted as the needles were inserted <5 mm superficially and about 2 cm away from the same acupoints selected as in the acupuncture group (AG). Chen et al. (25) reported that auricular acupuncture needles for sham auricular acupuncture were specially treated, which could not be inserted into skin.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included randomized clinical trials.

| First author (y) | Country | Age(y) | Gender (female/male) | Sample size | Drop out | Study design | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG | CG | AG | CG | (AG/CG) | (AG/CG) | |||

| Liao et al. (16) | China | 70 ± 4.7 | 71.4 ± 3.2 | 11/19 | 13/17 | 30/30 | 0/0 | RCT |

| Wang (17) | China | 53.3 ± 4.5 | 54.1 ± 6.2 | 25/29 | 23/28 | 54/51 | 0/3 | RCT |

| Zhang et al. (18) | China | 67 ± 7 | 67 ± 9 | 14/16 | 13/17 | 30/30 | 0/0 | RCT |

| Petersen et al. (24) | Denmark | 56 ± 8 | 56 ± 6.8 | 49/38 | 52/33 | 87/85 | 3/2 | RCT |

| Mikashima et al. (19) | Japan | 72 ± 7 | 73 ± 5 | 10/30 | 12/28 | 40/40 | 0/0 | RCT |

| Chen et al. (20) | Taiwan, China | 68.9 ± 9.0 | 69.0 ± 8.6 | 3/27 | 8/22 | 31/31 | 1/1 | RCT |

| Tsang et al. (25) | Hongkong, China | 70.6 ± 5.8 | 66.1 ± 7.5 | 4/14 | 3/15 | 18/18 | 3/3 | RCT |

| Mayoral et al. (21) | Spain | 72.27 ± 6.95 | 9/11 | 2/18 | 20/20 | 3/6 | RCT | |

| Wang (22) | China | 50~74 | 17/39 | 30/26 | 0/0 | RCT | ||

| First author (y) | Intervention | Start time | Acupuncture points | Needle retaining time | Intervention Dose | ||

| AG | CG | AG | CG | ||||

| Liao et al. (16) | Analgesia drugs, routine rehabilitation, traditional manual acupuncture | Analgesia drugs, routine rehabilitation | From 2 d before surgery to post-operative 2 w | LI4 and LR3 in both sides | 30 min | Once/d, 2w | |

| Wang (17) | Analgesia pump, traditional manual acupuncture | Analgesia pump | 2 d after operation | BL36, LR3, BL37, SP10, SP9, GB34 | Not mentioned. | Once/d, 2w | |

| Zhang et al. (18) | Analgesia pump, routine rehabilitation, traditional manual acupuncture | Analgesia pump, routine rehabilitation | 1 d after operation | LR3, BL 60, KI3, BL 62, SP6 and SI3 in the operated side; LU5, LI11, and LI10 in both sides | 30 min | Once/d, 2w | |

| Petersen et al. (24) | Standard rehabilitation, western medical acupuncture | Standard rehabilitation | (2.2 ± 1.3) w after operation | (2.4 ± 1.6) w after operation | ST32, GB31, GB39, ST41, and LR3 in the operated side; SP10, ST34, LR8, SP9, and ST36 in the opposite side | 15 20 min | Twice/w, 6w |

| Mikashima et al. (19) | Basic rehabilitation program, traditional manual acupuncture | Basic rehabilitation program | 7 d after operation | ST31, 32, 38; SP6; BL-23, 25, 37, 57, 60; KI3; GB31,39, 40, 41, 42, and LR3 in the operated side | 20 30 min | 3 times/w, 2w | |

| Chen et al. (20) | Auricular acupuncture and electroacupuncture | Only sham auricular acupuncture | Anesthetized and right before surgery started. | Auricular acupoints: TF4, AH4, AH6a and AT4; acupuncture points: SP10, ST34, BL40, LR7, ST36, GV20, and GV24 | 20 min | 1session only | |

| Tsang et al. (25) | Standard physiotherapy program and traditional manual acupuncture | Standard physiotherapy program and sham acupuncture | 4 d after operation | ST32, ST33, GB31, GB35, GB34 and ST36 | 20 min | 10 sessions within 2w | |

| Mayoral et al. (21) | Dry needling | Sham dry needling | Anesthetized and right before surgery started. | Myofascial trigger points | Hong's fast-in, fast-out technique | 1 session only | |

| Wang (22) | Standard physiotherapy program and traditional manual acupuncture | Standard physiotherapy program. | 3 d after operation | ST34, 35, 36, 41; SP10, SP9, GB33,34; LI4, BL40, EX-LE5 | 30 min | Twice/w, 6w | |

| First author (y) | Time points for evaluation | Main outcome | Conclusion | Adverse events |

| Liao et al. (16) | 1, 2, 7, 14 d after operation | VAS, KSS | A significant improvement in pain and function in the AG | None |

| Wang (17) | 14d after operation | VAS, HSS, ROM of knee | A significant improvement in pain and function in the AG | |

| Zhang et al. (18) | 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 h, 7, 14 d after operation | VAS, HSS, ROM of knee, Analgesic consumption, Analgesia-Related Adverse Effects | A significant improvement in pain and ROM in the AG | None |

| Petersen et al. (24) | 3 months of follow-up | KOOS pain, KOOS symptoms, KOOS-activities of daily living, KOOS quality of life, AROM-Ext, walking distance, No. with use of analgesics | No significant difference | None |

| Mikashima et al. (19) | 7, 10, 13, 15, 17, 19, and 21 d after operation. | VAS, ratio of swelling around knee, Time to achieve preoperative range of motion | A significantly reduced pain and swelling around the knees and earlier recovery of ROM in the AG than those in the CG | None |

| Chen et al. (20) | At 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after operation. | VAS, Analgesia-Related Adverse Effects, Analgesic consumption | A significant lower incidence of analgesia-related adverse effects of nausea and vomiting, and better pain control in the AG | None |

| Tsang et al. (25) | 4–8 d and 11–15 d after operation | Numeric pain rating scale, Analgesics consumption, ROM of knee, Time up to go test | Acupuncture is not superior to sham acupuncture in pain relief and improvements of ranges of knee motion in patients undergoing bilateral total knee arthroplasty | 2 patients refused to continue because of pain during acupuncture and 1 patient refused to continue because of pain during sham acupunctur |

| Mayoral et al. (21) | At 1, 3, 6 months after operation | VAS, WOMAC, ROM of knee, strength FLEX, and Strength EXT | A significant pain reduction in the first month after knee arthroplasty in the AG | None |

| Wang (22) | 18 d after operation. | HSS | A significant improvement in function of knee in the AG | None |

AG, acupuncture group; CG, control group; VAS: AG: visual analog scale; ROM, range of motion; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis and Outcome Score; HSS, Hospital for Special Surgery Knee Score; AROM-Ext, Active range of movement in knee extension (extension deficit); KSS, knee society score; TUG, time up to go test; RCT, randomized controlled trials.

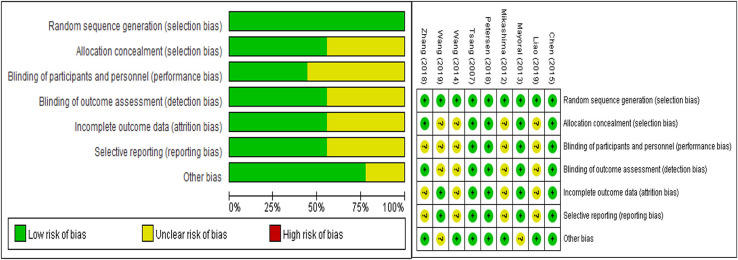

Risk of Bias

All the included studies were described as random generation, and five articles (18, 20–22, 24, 25) documented the methods of randomization in detail, in which a computer-generated random list was selected. Five of the 9 included studies recorded blind methods detailedly (20–22, 24, 25), and the dropout rate was reported in five articles (18, 20–22, 24, 25). The detailed results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph.

Meta-Analysis

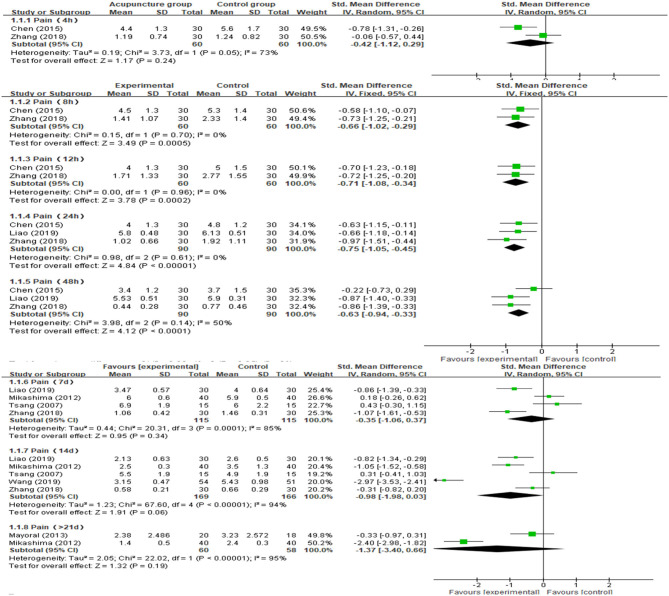

Post-operative Pain

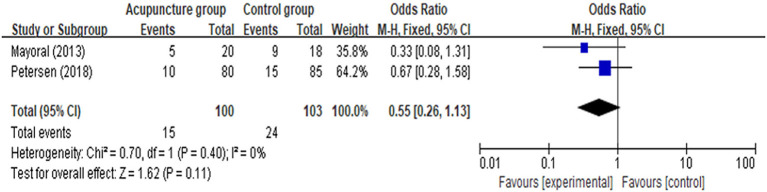

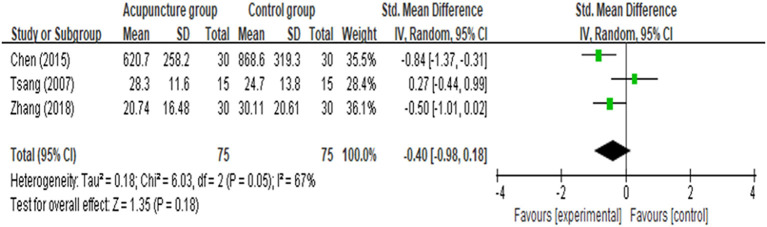

We preformed the meta-analyses to estimate the effects of acupuncture on pain at 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 h, 7, 14 days, and more than 21 days after TKA operation. From fixed-effects model, AG showed a significantly greater pain reduction compared with the CG at post-operative hour 8 [MD = −0.66 (95% CI: −1.02, −0.29), p = 0.0005, I2 = 0%], 12 [MD = −0.71 (95% CI: −1.08, −0.34), p = 0.0002, I2 = 0%], 24 [MD = −0.75 (95% CI: −1.05, −0.45), p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%], and 48 [MD = −0.63 (95% CI: −0.94, −0.33), p < 0.0001, I2 = 50%]. Analyses for the effect at the other time points in the post-operative period, including 4, 48 h, 7, 14 days, and more than 21 days, presented with substantial heterogeneity between the two groups (I2 = 73, 65, 87, 81, and 95%, respectively). Compared with CG, the results indicated AG had no statistically significant improvement in post-operative pain at 4 h [MD = −0.42 (95% CI: −1.12, 0.29), p = 0.24, I2 = 75%], 7 days [MD = −0.35 (95% CI: −1.06, 0.37), p = 0.34, I2 = 85%], 14 days [MD = −0.98 (95% CI: −1.98, 0.03), p = 0.06, I2 = 94%], and more than 21 days [MD = −1.37 (95% CI: −0.34, 0.66), p = 0.19, I2 = 95%] according to the random-effects model. Meta-analysis and forest plots are shown in Figure 3. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of patients with a score of more than 4 assessed by using VAS scale between the AG and the CG [OR = 0.55 (95% CI: 0.26, 1.13), p = 0.11, I2 = 0%; Figure 4]. In addition, no significant deference in post-operative analgesics consumption was observed between the both groups [MD = −0.14 (95% CI: −0.98, 0.18), p = 0.18, I2 = 67%; Figure 5].

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis and forest plot and for postoperative pain at different periods.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis and forest plot for number of patients with VAS score of more than 4.

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis and forest plot for analgesics consumption.

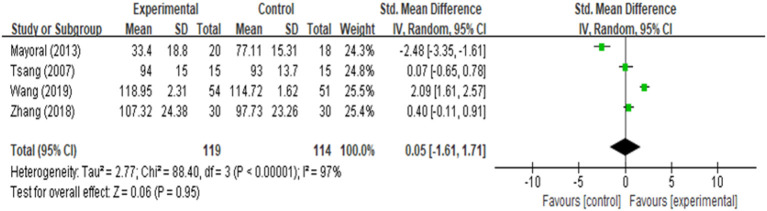

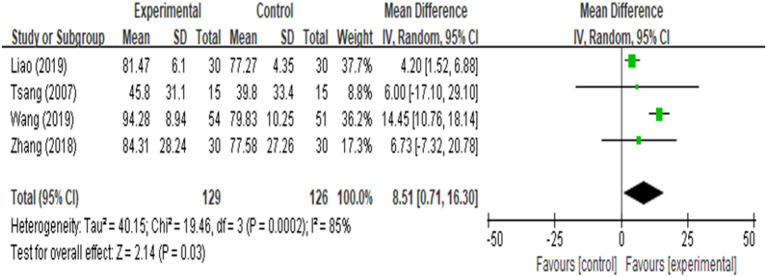

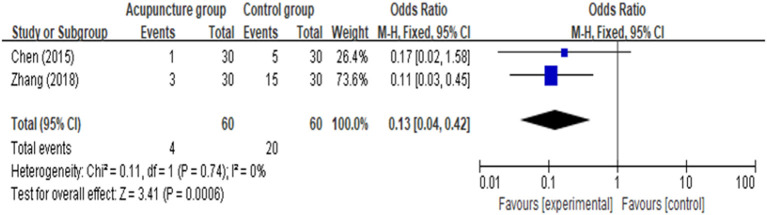

ROM, Function, and Nausea/Vomiting (An Analgesia-Related Adverse Effect)

ROM of knee was reported in four studies (17, 18, 21, 25), and the analysis result (Figure 6) revealed that it was closely similar in rehabilitation of knee ROM between AG and CG [MD = 0.05 (95% CI: −1.61, 1.71), p = 0.95, I2 = 97%]. Four of the 9 included studies documented function (16, 17, 22, 25), one of the three studies did not provide sufficient data, we attempted to contact authors but received no response. Four among the included studies reported function evaluated by using Hospital for Special Surgery Knee Score (HSS), either knee society score (KSS) or time up to go test (TUG). We found that there was a significant improvement in function [MD = 8.51 (95% CI: 0.71, 16.30), p = 0.03, I2 = 85%] between the AG and CG (Figure 7). However, meta-analysis of two studies (18, 20) showed AG had a significantly lower percentage of nausea/vomiting than the CG [OR = 0.13 (95% CI: 0.04, 0.42), p = 0.006, I2 = 0%; Figure 8].

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis and forest plot for ROM of knee.

Figure 7.

Meta-analysis and forest plot for function.

Figure 8.

Meta-analysis and forest plot for nausea/vomiting.

Sensitivity Analysis

In this study, we conducted sensitivity analyses of knee ROM by excluding one study in each turn to detect the source of heterogeneity, while the overall heterogeneities and results were stable (Table 2). The analysis of function resulted in high heterogeneity due to the different assessment methods. Thus, the subgroup analysis was performed by the function evaluation, and we found that there was a significant improvement in the AG when compared with the CG [MD = 4.29 (95% CI: 1.66, 6.92), p = 0.001, I2 = 0%; Supplementary Figure 2].

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis for ROM of knee.

| Studies | Effect size | 95% CI | P | I2 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mayoral et al. (21) | 0.87 | −0.42, 2.15 | 0.18 | 94 |

| Tsang et al. (25) | 0.03 | −2.19, 2.25 | 0.98 | 98 |

| Wang (17) | −0.64 | −2.24, 0.95 | 0.43 | 94 |

| Zhang et al. (18) | −0.09 | −2.65, 2.48 | 0.95 | 98 |

ROM, range of motion; CI, confidence intervals.

Publication Bias

In this study, Begg's test and Egger's test were selected to examine publication bias, and no evidence for significant publication bias was found among the included studies. However, Egger's test for trials on post-operative pain at hours 4, 8, and 12 and >21 days, and nausea/vomiting were not available due to only two included trials for each test (Supplementary Table 2).

Adverse Events

One of the included studies reported two patients in AG and one patient in CG refused to continue receiving acupuncture or sham acupuncture because of the intolerable pain.

Discussion

Many previous studies (30–32) suggested that acupuncture was a potential method for pain relief, and it was widely used for the treatment and rehabilitation of acute or chronic pain. In order to achieve an adequate post-operative pain management, acupuncture was applied to relieve pain for patients undergoing TKA. Although one previous meta-analysis (12) including four RCTs had examined the efficacy of acupuncture in post-operative pain after TKA, pain at only two evaluation time points after operation, namely post-operative days 2 and 8, were analyzed. In the current study, we investigated the effects of acupuncture on pain after TKA at more evaluation time points, adding new evidence on acupuncture for pain reduction in patients receiving TKA. We found that patients treated with acupuncture and basic rehabilitation demonstrated a significant pain improvement when compared with patients receiving basic rehabilitation only at post-operative hours 8, 12, 24, and 48. However, acupuncture, as an adjunctive therapy, exhibited no significant superiority of improvement in post-operative pain at 4 h, 7, 14 days, and more than 21 days. In post-operative period, patients receiving continuous regional anesthesia showed a lower pain (33). For the pain assessment at post-operative hour 4, an undetectable difference in pain improvement between both groups might be found due to interferences of anesthesia resuscitation period. Overall, with regard to post-operative pain, these findings are in accordance with the results from the previous meta-analysis (12), indicating that pain relief benefits concentrate in the early post-operative phase but were ineffective in the long run. Moreover, the number of patients with moderate to severe pain (VAS score >4) in the two groups were balance, which revealed that acupuncture was no superior to decrease the ratio of patients with severe pain after TKA. In addition, no significant difference in analgesics consumption between AG and CG indirectly revealed the unobvious effect of acupuncture on pain reduction for TKA patients.

Postoperative pain could limit knee ROM; our study showed no evidence to support that acupuncture had any benefit in improving knee ROM for patients undergoing TKA. TKA was associated with post-operative pain, and most of TKA patients experience moderate to severe pain after surgery, which was detrimental to restore joint ROM. As mentioned above, acupuncture had no significant benefit in reducing pain for patients receiving TKA; hence, it was not helpful to enhance effectiveness for knee ROM. However, function represented a comprehensive performance, which could be influenced by many factors including proprioception, coordination, muscle strength etc., in addition to pain. Therefore, a significantly greater function improvement was examined in the AG than that in the CG at post-intervention.

The results of analgesia-related adverse effects are particularly notable. Analgesia drugs can cause numerous adverse effects such as nausea/vomiting, respiratory depression, hypotension, and pruritus (34). All the analgesia-related side effects could not be neglected because of its high prevalence of morbidity and seriousness which would result in decreased life quality and even significant mortality after major surgery (35). Among them, nausea/vomiting is the most common. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture on nausea/vomiting for TKA. The finding from our analysis was that acupuncture could significantly reduce the ratio of nausea/vomiting for patients undergoing TKA. The present finding is comparable with that reported in Becker's study (36), indicating that acupuncture as a complementary method could reduce nausea and vomiting after surgery.

Some limitations of this review should be considered. Firstly, most of the included studies did not record random and blind methods in detail. Secondly, the acupoints selected for treatment and intervention dose in the 9 included studies are not consistent, which may have led to overestimations or underestimations of the reported effects. Thirdly, because of the different assessment methods, a small number of studies was pooled in the analysis for the outcomes, which could contribute to a publish bias. However, according to the Begg's test and Egger's test, no evidence for significant publication bias was detected. Nevertheless, further trials with robust methodology are required to make more firm conclusions.

Conclusion

In this work, we systematically reviewed and quantified the effects of acupuncture on post-operative rehabilitation for patients receiving TKA. Although acupuncture treatment exerted no positive effects on pain relief in the long stage and ROM of knee after TKA surgery, it achieved significant improvements in relieving the early post-operative pain and reducing the ratio of nausea/vomiting after TKA, which demonstrates that the use of acupuncture in the early post-operative period can be beneficial for the early post-operative rehabilitation. However, given the limitation in this study, additional high-quality and large-scale RCTs and systemic reviews are needed to confirm these findings.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

ZC and ZS designed the study. ZC and ZS did the literature searches and designed the data-extraction form. YX, TJ, and ZC selected studies. XS, WC, and ZS extracted the data. GC, WL, XY, JL, and ZS did statistical analyses. ZC, JW, and XX supervised the study. ZS did the language editing. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by Guangzhou Science and technology plan project (202002030204); Scientific research Project of Traditional Chinese medicine Bureau of Guangdong Province (No. 20194002); Soft Science Research Program of Guangdong Province (No. 2018B020207009); and Science and Technology Plan Project of Guangdong Province (2019A141401008).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2020.602564/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Chen Z, Shen Z, Ye X, Wu J, Wu H, Xu X. Association between foot posture asymmetry and static stability in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a case-control study. Biomed Res Int. (2020) 2020:1890917. 10.1155/2020/1890917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. (2019) 393:1745–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe WL, Dundon JM, Camus T. Alignment and balance methods in total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. (2018) 26:709–16. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canovas F, Dagneaux L. Quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. (2018) 104:S41–6. 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chughtai M, Elmallah RK, Cherian JJ, Mistry JB, Harwin SF, Mont MA. Rehabilitation and pain management modalities in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. (2016) 29:179 10.1055/s-0036-1580606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kehlet H. Postoperative pain, analgesia, and recovery-bedfellows that cannot be ignored. Pain. (2018) 159 (Suppl. 1):S11–6. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li JW, Ma YS, Xiao LK. Postoperative pain management in total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Surg. (2019) 11:755–61. 10.1111/os.12535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyer R, Ikert K, Long K, Marsh J. The Value of Preoperative Exercise and Education for Patients Undergoing Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JBJS Rev. (2017) 5:e2. 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan LJ, Zhang FR, Ma CS, Zheng Y, Chen JT, Li W. Arteriovenous graft for hemodialysis: effect of cryotherapy on postoperative pain and edema. Pain Manag Nurs. (2019) 20:170–3. 10.1016/j.pmn.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen D, Sheng D, Xu JL, Zhang YY, Lin TY, Zhang QW. Electroacupuncture intervention reduces post-surgical pain of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. (2018) 43:616–21. 10.13702/j.1000-0607.180404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arslan H, Ahmed HMA, Yildiz ED, Gündogdu EC, Seçkin F, Arslan S. Acupuncture reduces the postoperative pain in teeth with symptomatic apical periodontitis: a preliminary randomized placebo-controlled prospective clinical trial. Quintessence Int. (2019) 50:270–77. 10.3290/j.qi.a42153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen T, Zhang WW, Chu YX, Wang YQ. Acupuncture for pain management: molecular mechanisms of action. Am J Chin Med. (2020) 48:793–811. 10.1142/S0192415X20500408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vickers A, Zollman C. ABC of complementary medicine. Acupuncture. BMJ. (1999) 319:973–6. 10.1136/bmj.319.7215.973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu MS, Chen KH, Chen IF, Huang SK, Tzeng PC, Yeh ML, et al. The efficacy of acupuncture in post-operative pain management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0150367. 10.1371/journal.pone.0150367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tedesco D, Gori D, Desai KR, Asch S, Carroll IR, Curtin C, et al. Drug-free interventions to reduce pain or opioid consumption after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. (2017) 152:e172872 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao Z, Danchun L, Shichang H, Bingxuan Y. Effect of acupuncture at Siguan combined with celecoxib on perioperative preemptive analgesia in patients with total knee arthroplasty. Chin J Gerontol. (2019) 39:3688–90. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2019.15.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D. Effect of acupuncture combined with femoral nerve block on knee joint function in patients after knee arthroplasty. Zhe J Integr Trad Chin West Med. (2019) 29:923–24. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2019&filename=ZJZH201911018&v=pc9UrDPICdOpQpRGGq7Fss6VmUNoTIeJ2iHq12xRLcnSnlRxtVYoyorplnxfj4Ca [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Zhang L, Lu M. Acupuncture combined with femoral nerve block for postoperative analgesia after total knee arthroplasty and functional rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. (2018) 38:251–5. 10.13703/j.0255-2930.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikashima Y, Takagi T, Tomatsu T, Horikoshi M, Ikari K, Momohara S. Efficacy of acupuncture during post-acute phase of rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty. J Tradit Chin Med. (2012) 32:545–8. 10.1016/S0254-6272(13)60068-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen CC, Yang CC, Hu CC, Shih HN, Chang YH, Hsieh PH. Acupuncture for pain relief after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. (2015) 40:31–6. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayoral O, Salvat I, Martín MT, Martín S, Santiago J, Cotarelo J, et al. Efficacy of myofascial trigger point dry needling in the prevention of pain after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2013) 2013:694941. 10.1155/2013/694941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X. Effect of acupuncture and moxibustion on functional recovery after total knee arthroplasty. Lia J Tradit Chin Med. (2014) 41:1653–54. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J, Qu Y, Yue Y, Zhao H, Gao Y, Peng L, Zhang Q. Treatment of persistent hiccups after arthroplasty: effects of acupuncture at PC6, CV12 and ST36. Acupunct Med. (2019) 37:72–6. 10.1136/acupmed-2016-011304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen T, Hautopp H, Duus B, Juhl C. No Effect of acupuncture as adjunctive therapy for patients with total knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. (2018) 19:1280–9. 10.1093/pm/pnx317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsang RC, Tsang PL, Ko CY, Kong BC, Lee WY, Yip HT. Effects of acupuncture and sham acupuncture in addition to physiotherapy in patients undergoing bilateral total knee arthroplasty–a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2007) 21:719–28. 10.1177/0269215507077362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. (2015) 350:g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration' s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:889–93. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index?. Psychol Methods. (2006) 11:193–206. 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1. Cochrane. (2020). Available online at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 30.Yuan QL, Wang P, Liu L, Sun F, Cai YS, Wu WT, et al. Acupuncture for musculoskeletal pain: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of sham-controlled randomized clinical trials. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:30675. 10.1038/srep30675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vickers AJ, Linde K. Acupuncture for chronic pain. JAMA. (2014) 311:955–6. 10.1001/jama.2013.285478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly RB, Willis J. Acupuncture for pain. Am Fam Phys. (2019) 100:89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bugada D, Allegri M, Gemma M, Ambrosoli AL, Gazzerro G, Chiumiento F, et al. Effects of anaesthesia and analgesia on long-term outcome after total knee replacement: a prospective, observational, multicentre study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2017) 34:665–72. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vicari JJ. Sedation and analgesia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. (2002) 12:297-311, viii. 10.1016/S1052-5157(01)00011-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He BJ, Tong PJ, Li J, Jing HT, Yao XM. Auricular acupressure for analgesia in perioperative period of total knee arthroplasty. Pain Med. (2013) 14:1608–13. 10.1111/pme.12197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee A, Chan SK, Fan LT. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point PC6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 2015:CD003281. 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.