Abstract

Purpose

Ifosfamide can lead to a syndrome of central nervous system (CNS) toxicity. Here we investigate the clinical and electroencephalographic (EEG) characteristics of patients with ifosfamide-related encephalopathy.

Methods

Retrospective data were collected on patients from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, who developed encephalopathy associated with ifosfamide between 2007 and 2017. Patients who had an EEG performed were included. Clinical and laboratory data were retrospectively collected. Each EEG recording was reviewed and compared with the originally documented EEG report.

Results

Sixteen (16) patients with ifosfamide-related encephalopathy were included, with primary tumors consisting of lymphoma (N=9), sarcoma (N=4), poorly differentiated ovarian cancer (N=1), neuroblastoma (N=1), and papillary serous adenocarcinoma (N=1). Laboratory results ruled out other etiologies of encephalopathy. Generalized periodic discharges (GPDs) with or without triphasic morphology were seen most commonly (N=9), with a distinct pattern of interspersed intermittent background attenuation seen in 5 patients. Background slowing and intermittent rhythmic delta activity (N=4), bursts of bilateral synchronized delta activity (N=2), and frontal predominant intermittent delta activity (N=1) were also seen. One patient demonstrated a pattern consistent with nonconvulsive status epilepticus. While most patients experienced resolution of symptoms, those who died demonstrated a variety of EEG abnormalities. Abnormal movements were common, with six patients demonstrating characteristic orofacial myoclonus.

Conclusions

Ifosfamide related encephalopathy commonly results in a distinct pattern of GPDs admixed with intermittent background attenuation on EEG. Abnormal movements, in particular orofacial myoclonus, are also common. Recognizing these clinical and EEG features might lead to early detection of ifosfamide-related encephalopathy.

Keywords: Ifosfamide, encephalopathy, electroencephalography, generalized periodic discharge

INTRODUCTION

Ifosfamide, an alkylating chemotherapeutic agent, is used alone or in combination with other agents to treat various solid tumors such as ovarian, testicular, head and neck, and sarcomas as well as lymphoma (2,10). In addition to complications such as myelosuppression, hemorrhagic cystitis, nausea, and vomiting, a syndrome of ifosfamide-related central nervous system (CNS) toxicity has been described (14). Treatment with high-dose ifosfamide can result in an encephalopathy which commonly occurs from 12 hours to 6 days after treatment initiation (10,14). The CNS symptoms are along a spectrum of severity. The CNS symptoms typically improve within 48–72 hours after discontinuation (10,14), however encephalopathy can in some cases lead to coma and death (17). Predisposing factors for ifosfamide-related encephalopathy include higher doses, poor functional status at treatment initiation, concomitant cisplatin treatment, renal failure, hepatic insufficiency, and low serum albumin levels (2,14).

The toxic metabolite chloroacetaldehyde may cause encephalopathy due to the depletion of cerebral glutathione (10,18). Ifosfamide’s parent compound, cyclophosphamide, does not undergo dechloroethylation, which liberates chloroacetaldehyde, and likely accounts for its lack of CNS toxicity (14). The metabolite chloroethylamine may also contribute by inhibiting flavoprotein dependent mitochondrial respiration, resulting in accumulation of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), preventing the dehydrogenation of chloroacetaldehyde and promoting its accumulation (17). To date there is no effective treatment for the reversal of ifosfomide toxicity however methylene blue and thiamine have been used with varying efficacy (10,21).

Ifosfamide-related encephalopathy often prompts evaluation with electroencephalography (EEG). Several patterns of EEG changes in ifosfamide-related encephalopathy have been described, however all have been limited to small case reports. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) can occur in ifosfamide-related encephalopathy, although it seems to occur in a minority of affected patients (5,9). It has been suggested that EEG changes may correlate with the severity of ifosfamide-related toxicity with generalized slowing or generalized period discharged (GPDs) with triphasic morphology in minimally affected patients, epileptiform discharges in those moderately affected, and NCSE in the most severely affected (5).

In this study, we sought to evaluate the EEG changes in a cohort of patients with ifosfamide-related encephalopathy in association with their clinical presentations in order to uncover clinical and electroencephalographic features unique to ifosfamide-related encephalopathy.

METHODS

Patient data was retrospectively analyzed from a single tertiary care center, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). Search results included all patients who developed ifosfamide-related encephalopathy during hospitalization and yielded 41 patients. Between the years of 2007 and 2017, 16 of those patients had long-term video EEG records available for review. Clinical and laboratory data were retrospectively abstracted for each patient through the electronic medical record. Each EEG was reviewed and interpreted by a board-certified neurophysiologist (XC). Continuous video EEG recordings were performed with Natus 32-channel computerized EEG system with standard 10–20 electrode montages. Standard American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (ACNS) terminology (7) was used for interpretation. Study subjects had full blood cell counts, comprehensive chemistry panels, ammonia, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and vitamin B12 levels to exclude common causes of encephalopathy. The MSKCC institutional review board approved this study.

RESULTS

We included 16 patients with ifosfamide-related encephalopathy and continuous EEG monitoring. Demographic data and clinical information are shown in Table 1. Age range was from 14 to 70 years, with a median of 55 years. There were 11 female and 5 male patients. Malignancies being treated included lymphoma (N=9), sarcoma (N=4), poorly differentiated ovarian tumor (N=1), neuroblastoma (N=1), and papillary serous adenocarcinoma (N=1). Time from ifosfamide infusion to symptoms ranged from 1–2 hours to 60 hours (median 24 hours). Patients had been treated with 1500 mg/m2 to 5000 mg/m2 ifosfamide (median 2500 mg/m2). Treatments included methylene blue (N=13), thiamine (N=10), urine alkalinization (N=1), and decreased infusion rate (N=1). The majority experienced resolution of their symptoms (N=11). Symptoms did not resolve and eventually led to death in 5 patients.

Table 1:

Demographics and clinical data

| # | Age | Gender | Primary Cancer | Dose mg/m2 | Time to Symptom Onset (h) | EEG Features | Abnormal Movements | Initial Symptoms | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | F | Sarcoma | 2500 | 24 | Triphasics, Frontal predominant intermittent delta | Yawning | Hallucinations | Resolved |

| 2 | 17 | M | Lymphoma | 5000 | 48 | R frontal seizure, NCSE, bursts of bilateral synchronized delta | None | Disoriented, inattentive | Deceased |

| 3 | 45 | F | Lymphoma | 2500 | 24 | Intermittent delta activity | None | Disoriented, inattentive | Deceased |

| 4 | 51 | M | Lymphoma | 1500 | 36 | Diffuse mild background slowing | Orofacial myoclonus | Disoriented, inattentive | Improved |

| 5 | 64 | F | Lymphoma | 5000 | 24 | Triphasic waves with various attenuation | Arm myoclonus, orofacial myoclonus | Disoriented, inattentive | Improved |

| 6 | 68 | F | Lymphoma | 2500 | 24 | Triphasics, attenuation | None | WFD, inattentive | Resolved |

| 7 | 70 | F | Lymphoma | 2500 | 24 | Background slowing | None | Disoriented | Resolved |

| 8 | 58 | M | Lymphoma | 5000 | 36 | Slowing, intermittent delta | Tremulous, multifocal myoclonus | Inattentive, paucity of speech | Resolved |

| 9 | 46 | F | Sarcoma | 2500 | 24 | Triphasics, attenuation | Tremor, orofacial myoclonus, yawning |

Lethargy, GTC seizure | Resolved |

| 10 | 69 | M | Lymphoma | 5000 | 24 | Triphasics, attenuation | Myoclonic jerking, orofacial myoclonus | Inattentive | Deceased |

| 11 | 20 | F | Sarcoma | 2800 | 1 | Normal | None | Disoriented, inattentive | Resolved |

| 12 | 57 | F | Lymphoma | 5000 | 48 | Delta, triphasics, attenuation | None | Unsteady gait, disoriented | Resolved |

| 13 | 57 | F | Sarcoma | 2500 | 24 | Triphasics | Orofacial myoclonus | WFD, unsteady gait | Resolved |

| 14 | 31 | F | Poorly Differentiated Ovarian Tumor | 1500 | 48 | Slowing, triphasics | Orofacial myoclonus | Lethargy, Inattention | Resolved |

| 15 | 14 | M | Neuroblastoma | 1500 | 60 | Bilateral synchronized delta | None | Lethargy | Resolved |

| 16 | 66 | F | Papillary Serous Adenocarcinoma | 2000 | 24 | Triphasics, intermittent delta | Myoclonic jerks | Aphasia | Resolved |

The presentation of each patient included disorientation, delirium, or inattentiveness (N=16), and the majority had somnolence or lethargy (N=13). Aphasia or mutism was present in 4 patients, while only one presented with a generalized tonic clonic seizure, and one with hallucinations. Two patients had an unsteady gait on presentation (Table 2). The most common EEG feature was GPDs with triphasic morphology (Figure 1A, N=9) followed by a special pattern of GPDs interspersed with periods of background attenuation (2–4 seconds) between discharges, which was seen in 5 patients (Figure 1B,C). Background slowing (N=4) and intermittent rhythmic delta activity were also seen (N=4). Less common was occasional frontally predominant generalized rhythmic delta activity (GRDA, N=1) or bursts of bilateral synchronized rhythmic delta activity (N=2). EEG was consistent with NCSE in only one patient. Of those who died during the hospitalization, EEG was characterized by NCSE and bursts of bilateral synchronized rhythmic delta activity (N=2), diffuse background slowing (N=1), or GPDs with triphasic morphology with interspersed background attenuation (N=2). Myoclonus was observed in 4 patients, characterized by multifocal myoclonus (N=3), or arm myoclonus (N=1). Six patients also exhibited what we hereafter will refer to as orofacial myoclonus including grimacing, grunting, eye opening and closing, smacking and chewing movements. We did not observe any choreiform or dystonic movements. None of them demonstrated epileptiform activities such as eyelid fluttering, gaze deviation or unilateral facial muscle twitching. These patients demonstrated characteristic facial movements, which we were also able to capture and revealed no clear EEG correlation except muscle artifacts. The movements did not seem to be EEG state dependent.

Table 2:

Presentation of Patients with Ifosfamide toxicity

| Clinical Presentation | N= | EEG Characteristics | N= |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disorientation/Delirium/Inattentive | 16 | Generalized periodic discharges with triphasic morphology | 9 |

| Aphasia/Dysphasia | 8 | Frontal predominant generalized rhythmic delta activity | 1 |

| Somnolence/Lethargy | 13 | NCSE | 1 |

| Seizures | 2 | Bursts of bilateral synchronized delta | 2 |

| Diffuse Tremor/Myoclonus | 5 | Intermittent delta activity | 4 |

| Facial Myoclonus | 9 | Background slowing | 4 |

| Hallucinations | 1 | Attenuation | 5 |

| Unsteady Gait | 2 | ||

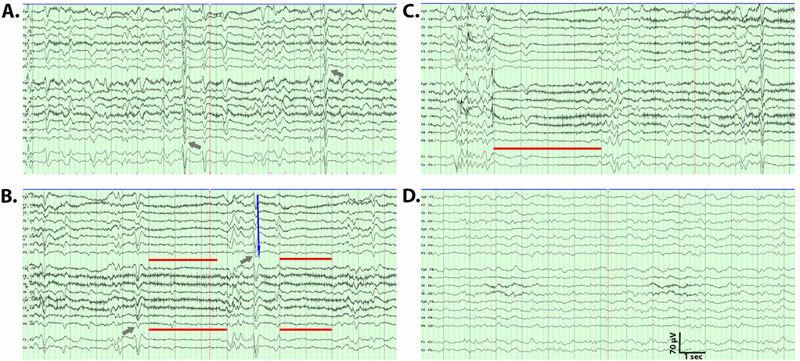

Figure 1:

Representative electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns. Conventional bipolar EEG montage is shown for a patient with a pattern of generalized period discharges (GPDs) with triphasic morphology (A) with each triphasic wave indicated by a blue arrow. A characteristic example of GPDs with triphasic morphology waves (gray arrows) followed by periods of attenuation of 2–3 seconds noted with gray lines (B). Example of an EEG (C) demonstrating longer periods of attenuation (4 seconds, red line). EEG during sleep demonstrating a poorly organized background without GPD (D).

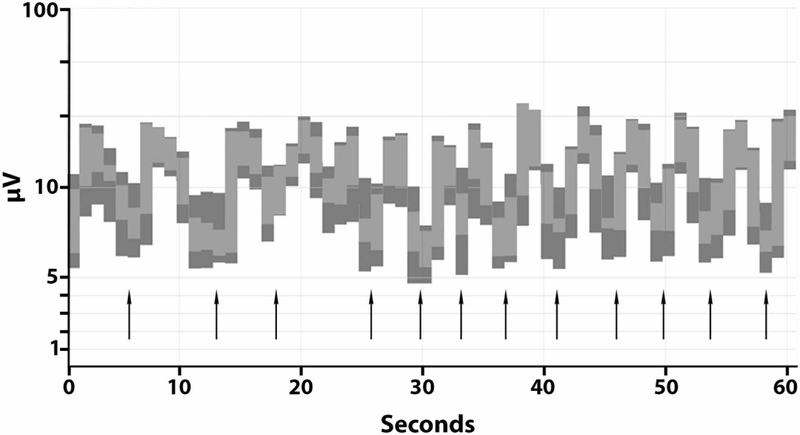

The pattern of GPDs with triphasic morphology admixed with attenuation was further investigated with amplitude-integrated EEG. As shown in Figure 2, over a period of 1 minute of recording, 12 episodes of attenuation were recorded (indicated with arrows), lasting up to four seconds. The periods of attenuation were characterized by voltages as low as 5 μV (Figure 2). Further examination of the GPDs with triphasic morphology revealed a maximum positive amplitude from 16 to 42 μV. There was a slight anterior to posterior lag (Figure 1B, blue arrow). This pattern did not persist during sleep (Figure 1D).

Figure 2.

Amplitude-integrated EEG demonstrating 12 episodes of brief attenuation of background amplitude within a period of one minute. Each black arrow indicates one period of attenuation.

Neuroimaging was obtained in 13 of the patients, with no intracranial abnormalities detected in 11 patients. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed on patient number 8 demonstrated small foci of restricted diffusion in the posterior left frontal lobe and right occipital lobe consistent with acute infarct. MRI brain performed on patient number 13 revealed minimal periventricular and subcortical chronic white matter microvascular ischemic changes.

Routine laboratory studies were obtained for each patient. Albumin was commonly low (median 3.10, interquartile range (IQR) 2.58–3.18). Significant renal impairment was not present (median creatinine 1.1, IQR 0.7–1.4; median estimate glomerular filtration rate 60, IQR 47–60). Other causes of encephalopathy were not found with no patients demonstrating elevated ammonia, low vitamin B12, or abnormal TSH. Most had normal liver function (median ALT 19.0, IQR 11.5–46.5; median AST 25.0, IQR 13.8–41.5).

DISCUSSION

Ifosfamide treatment is known to result in serious encephalopathy with high mortality rates as confirmed in our study; however, no unique clinical or EEG features have hitherto been reported. Herein, we report clinical and EEG features of ifosfamide-related encephalopathy in the largest cohort of patients to date. We show that ifosfamide-related encephalopathy, in addition to causing background slowing, rhythmic delta activity and GPDs with or without triphasic morphology, commonly produces interspersed periods of background attenuation lasting 2 to 4 admixed with GPDs with triphasic morphology. We also report a characteristic pattern of orofacial myoclonus during the period of encephalopathy.

Time to onset of symptoms (median 24 hours), fits with a previously reported range of 12 to 146 hours (11,14), however in patient number 11 symptoms occurred after only 1–2 hours (Table 1). This may be attributed to early detection of mild symptoms in this patient, with resolution of symptoms occurring after decreasing ifosfamide. Our results are consistent with higher doses of ifosfamide correlating with symptom severity. Median ifosfamide dose among those who died was 5000mg/m2. No other etiologies for encephalopathy were found. Significant renal impairment was not present and only mild transaminitis was found, with no patients demonstrating an elevated ammonia. However, our data support the previously reported association between low serum albumin and ifosfamide-related encephalopathy (2) with our patients having a median albumin of 3.1.

White matter has been implicated in the development of GPDs with triphasic morphology (8). Reverberating corticothalamic inputs may suppress the sequential activation of midline thalamic reticular nuclei, which are thought to play a role in the development of GPDs with triphasic morphology. Acquired white matter disease impairs corticothalamic input, allowing for the thalamic generation of GPDs with triphasic morphology (8,16). However, in the patients reported herein, neuroimaging revealed only mild white matter disease in one patient. Additional work will be needed to understand the mechanisms underlying the electrophysiological patterns seen in patients with ifosfamide toxicity. However, it is possible that, similar to ammonia, ifosfamide may affect cerebral gamma-aminobutyric acid tone and postsynaptic neuron inhibition (8,16).

Orofacial myoclonus has not been reported to our knowledge in associated with ifosfamide toxicity. One previous case report notes, as non-convulsive status epilepticus, eyelid fluttering and facial myoclonus correlating with 0.5 to 1 second periods of attenuation following GPDs with triphasic morphology (19). Here we observed stereotypical involuntary facial movements, which we have referred to as orofacial myoclonus in 6 patients and attenuation following GPDs with triphasic morphology in 5 patients (31%). Orofacial movements are commonly observed as a side effect of chronic use of dopamine D2 receptor antagonists, such as typical antipsychotic drugs or metoclopramide. The underlying mechanism is thought to be due to a compensative over-activity of dopaminergic neuronal activity or reduced GABAergic neuronal activity (1). These orofacial myoclonus resemble the movement disorders observed in other acute, diffuse brain dysfunction such as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, where epileptic and non-epileptic events are intermixed (3,6). Using the Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability assessment tool, ifosfamide is considered the probable culprit in our series with a score of 7 (13). Our findings suggest that orofacial myoclonus occur commonly and may be characteristic of severe ifosfamide-related encephalopathy, even in the absence of correlated epileptic discharges.

These movements have not been described in prior case reports or series. The series by Savica et al describes movement disorders as associated with ifosfamide neuro-toxicity and notes the presence of generalized myoclonus as being a sign of CNS toxicity. By contrast in our series, generalized myoclonus was observed only observed in 4 patients, with more orofacial myoclonus present in 6 patients (15). Our series also founds that orofacial myoclonus can occur independently of generalized myoclonus. Moreover, in comparison to Wernicke’s which can lead to a syndrome of encephalopathy with a movement disorder, most commonly choreoathetosis and dystonia (12,20), the myoclonus observed in our case series is distinct. The movements observed are intermittent, recurrent, spasmodic and would occur with no associated eyelid fluttering, ophthalmoparesis or gaze deviation. Further, there was no EEG correlate to suggest that these movements are epileptic in nature.

It has been suggested that a continuum of EEG findings exists, with slowing representing mild and NCSE representing severe ifosfamide-related encephalopathy (5). Among the patients who died in our study, only one had NCSE, while others had GPDs with triphasic morphology with attenuation or slowing. Therefore, our results do not support the notion that the most severe cases of ifosfamide-related encephalopathy are associated with NCSE. GPDs with triphasic morphology admixed with periodic attenuation and background slowing may also be associated with poor outcomes.

Our results demonstrate that EEG pattern of GPDs with interspersed background attenuations associated with characteristic orofacial myoclonus are associated with ifosfamide-related encephalopathy. While GPDs with triphasic morphology have been reported in a variety of metabolic encephalopathies (4), the periods or marked attenuation seen on conventional EEG montages and highlighted on amplitude-integrated EEG seem to be related to ifosfamide-related encephalopathy and may be associated with poor outcome. These patterns may help to identify patients whose encephalopathy is due to ifosfamide treatment and may provide insight into outcomes. We suggest that prolonged video EEG recording should be performed in patients with encephalopathy thought to be due to ifosfamide treatment to facilitate the detection of these EEG patterns and orofacial myoclonus.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Daniel Kelly for help with the identification of patients for inclusion in this study.

Author disclosures:

Aaron Gusdon – received support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81550110260)

Rachna Malani – Nothing to disclose

Xi Chen – Nothing to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Cornett EM, Novitch M, Kaye AD, Kata V, Kaye AM. Medication-Induced Tardive Dyskinesia: A Review and Update. Ochsner J. 2017;17(2):162–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David KA, Picus J. Evaluating risk factors for the development of ifosfamide encephalopathy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28(3):277–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duan B, Weng W, Lin K, et al. Variations of movement disorders in anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Med. 2016;0(July):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faigle R, Sutter R, Kaplan PW. The electroencephalography of encephalopathy in patients with endocrine and metabolic disorders. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30(5):1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feyissa AM, Tummala S. Ifosfamide related encephalopathy: The need for a timely EEG evaluation. J Neurol Sci. 2014;336(1–2):109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granata T, Matricardi S, Ragona F, et al. Original article Pediatric NMDAR encephalitis : A single center observation study with a closer look at movement disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018;22(2):301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsch LJ, Laroche SM, Gaspard N, et al. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society’s Standardized Critical Care EEG Terminology: 2012 version. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2013;30(1):1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan PW, Sutter R. Affair with Triphasic Waves - Their Striking Presence, Mysterious Significance, and Cryptic Origins: What are They? J Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;32(5):401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kilickap S, Cakar M, Onal IK, et al. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus due to ifosfamide. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(2):332–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee EQ, Arrillaga-Romany IC, Wen, Patrick Y. Neurologic complications of cancer drug therapies. Continuum (N Y). 2012;18(2):355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meanwell CA, Blake AE, Latief TN, et al. Encephalopathy Associated with Ifosphamide/Mesna Therapy. Lancet. 985;1(8425):406–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moodley R, Seebaran AR, Rajput MC. Dystonia and choreo-athetosis in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1989;75(11):543–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of averse drug reactions. 1981. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Nicolao P, Giometto B. Neurological toxicity of ifosfamide. Oncology. 2003;65(SUPPL. 2):11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savica R, Rabinstein AA, Josephs KA. Ifosfamide associated myoclonus-encephalopathy syndrome. J Neurol. 2011;258(9):1729–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shawcross D, Jalan R. The pathophysiologic basis of hepatic encephalopathy: Central role for ammonia and inflammation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(19–20):2295–2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin Y-J, Kim J-Y, Moon J-W, You R-M, Park J-Y, Nam J-H. Fatal Ifosfamide-Induced Metabolic Encephalopathy in Patients with Recurrent Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Report of Two Cases. Cancer Res Treat. 2011;43(4):260–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sood C, O’Brien PJ. 2-Chloroacetaldehyde-induced cerebral glutathione depletion and neurotoxicity. 1996. Epub. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Taupin D, Racela R, Friedman D. Ifosfamide Chemotherapy and Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus : Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2014;45(3):222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon JH, Yong SW, Yong SW, Lee PH. Dystoinc hand tremor in a patient with Wernicke encephalopathy. Park Relat Disord. 2009;15(6):479–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zulian GB, Tullen E, Maton B. Methylene blue for ifosfamide-associated encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(18):1239–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]