Abstract

Background

In severe bronchiolitis, it is unclear if delayed clearance or sequential infection of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or rhinovirus (RV) is associated with recurrent wheezing.

Methods

In a 17-center severe bronchiolitis cohort, we tested nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPA) upon hospitalization and 3 weeks later (clearance swab) for respiratory viruses using PCR. The same RSV subtype or RV genotype in NPA and clearance swab defined delayed clearance (DC); a new RSV subtype or RV genotype at clearance defined sequential infection (SI). Recurrent wheezing by age 3 years was defined per national asthma guidelines.

Results

Among 673 infants, RSV DC and RV DC were not associated with recurrent wheezing, and RSV SI was rare. The 128 infants with RV SI (19%) had nonsignificantly higher risk of recurrent wheezing (hazard ratio [HR], 1.31; 95% confidence interval [CI], .95–1.80; P = .10) versus infants without RV SI. Among infants with RV at hospitalization, those with RV SI had a higher risk of recurrent wheezing compared to children without RV SI (HR, 2.49; 95% CI, 1.22–5.06; P = .01).

Conclusions

Among infants with severe bronchiolitis, those with RV at hospitalization followed by a new RV infection had the highest risk of recurrent wheezing.

Keywords: delayed clearance, sequential infection, respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, recurrent wheezing

In a prospective, multicenter cohort of infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis, we found those with rhinovirus infection at hospitalization followed by a different rhinovirus genotype infection 3 weeks later had the highest risk of recurrent wheezing by age 3 years.

Bronchiolitis is a viral respiratory infection with substantial acute and chronic morbidity [1, 2]. Indeed, bronchiolitis is the leading cause of infant hospitalization in the United States [1] and up to 40% of infants with severe bronchiolitis (ie, bronchiolitis requiring hospitalization) will develop recurrent wheezing and childhood asthma [2–6]. Most severe bronchiolitis cohorts examining chronic morbidity outcomes have focused on the relation of the most common viral infections at the time of hospitalization (respiratory syncytial virus [RSV] and rhinovirus [RV]) to subsequent outcomes of recurrent wheezing and asthma [2–6].

However, no study has examined if—in the weeks after hospitalization—detection of the same virus (ie, delayed clearance [DC]) or a different virus (ie, sequential infection [SI]) is associated with these respiratory outcomes. In infants with severe bronchiolitis either DC or SI may be particularly important. The lungs of infants continue to develop for years after birth [7] and an ongoing host inflammatory response associated with either prolonged or sequential exposure to viral infection [8, 9] may ultimately damage the structure and impair the function of the lungs [10].

In a previous analysis, we found that among infants hospitalized with RSV bronchiolitis, 19% have RSV DC [11]. However, we did not examine whether these children were at higher risk of recurrent wheezing, nor did we address SI. To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a planned secondary analysis of our prospective, multicenter study of infants with severe bronchiolitis to examine the association between the detection of RSV and RV in the weeks following hospitalization and the risk of recurrent wheezing. We hypothesized that RSV DC and RV SI would be associated with increased risk of recurrent wheezing.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

As previously described, the 35th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-35) is a prospective, 17-center cohort study of infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis during the 2011–2014 winter seasons [12]. Briefly, teams at participating sites consecutively enrolled infants (age <1 year) hospitalized for bronchiolitis who met the American Academy of Pediatrics definition of bronchiolitis [13]. Exclusion criteria included known heart-lung disease and gestational age <32 weeks. All patients were treated at the discretion of the care team. The institutional review board at each of the participating hospitals approved the study.

Data Collection

Study staff conducted structured interviews with parents/guardians to obtain data on the participant’s medical and environmental history and bronchiolitis episode. Additionally, study staff obtained clinical data on the participant’s evaluation, treatment, and course from the medical record. Post hospitalization, parents completed biannual telephone follow-up interviews.

Nasopharyngeal Aspirate and Nasal Swab Collection

As previously published, site researchers collected nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) within 24 hours of hospitalization and trained parents to collect nasal swabs [11]. Parents collected nasal swabs 3 weeks after the date of hospitalization (ie, clearance swab) because up to 25% of children with bronchiolitis will continue to be symptomatic 3 weeks after presentation [14]. At the time of clearance swab collection, parents completed a form to report symptoms in the child including cough, runny nose, fever, hoarseness, tachypnea, wheezing, and retractions. The analysis was limited to participants with clearance swabs.

Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assays were conducted at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, for 17 viruses, including RSV types A and B and RV [15].

RSV Sequencing and RV Molecular Typing

At Baylor College of Medicine, the Sanger method was used to sequence the second hypervariable region of the G gene for RSV-positive NPA and clearance swabs [11]. Infants with sequenced NPA and clearance swabs had identical sequences or 1 amino acid difference [11].

At University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, RVs were partially sequenced (5′ untranslated region and VP2-VP4 fragment, if needed) to identify the species and genotypes of RV-positive NPA and clearance swabs [16].

Exposures and Outcome Measures

RSV DC was defined as presence of the same RSV subtype in the hospitalization NPA and the clearance swab [11] (Supplementary Figure 1). RV DC was defined as presence of the same RV genotype in the hospitalization NPA and the clearance swab. RSV SI was defined as presence of a new RSV subtype in the clearance swab not present in the hospitalization NPA. We did not evaluate RSV SI further due to the small sample size (n = 3). RV SI was defined as presence of a new RV genotype in the clearance swab not present in the hospitalization NPA. This category included infants without RV at hospitalization, as well as infants who had RV at hospitalization and a different RV genotype at clearance.

The outcome was recurrent wheezing by age 3 years, defined as having ≥2 corticosteroid-requiring exacerbations in 6 months or ≥4 wheezing episodes in 1 year that last at least 1 day and affect sleep, per the 2007 National Institutes of Health asthma guidelines [17]. Outcomes were obtained via biannual parent interview.

Statistical Methods

We compared the characteristics of the analytic cohort (infants who provided a nasal swab) vs the nonanalytic cohort (infants who did not provide a nasal swab) using χ2 tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate. We compared the survivor functions for development of recurrent wheezing in the analytic vs nonanalytic cohort using a log-rank test for equality of survivor functions.

Delayed Clearance

RSV DC analyses were restricted to infants with RSV infection at the index hospitalization. Previously, we compared the characteristics of participants with vs without RSV DC using χ2, Fisher exact, and Kruskal-Wallis tests [11]. We assessed the unadjusted associations of RSV DC and baseline characteristics to recurrent wheezing using Cox proportional hazards models and Kaplan-Meier plots. We selected model covariates based on unadjusted associations with recurrent wheezing and known risk factors for recurrent wheezing. For each variable, we tested the proportional hazards assumption required by the Cox model using the Schoenfeld residuals. As previously described [18], hazards were not proportional by age at enrollment. Therefore, we stratified the adjusted Cox models by age at enrollment, dichotomized as <2 months vs ≥2 months based on the Kaplan-Meier plots. We built a parsimonious model which excluded several variables that were not associated with recurrent wheezing (eg, postnatal smoke exposure, breastfeeding history, and paternal history of asthma). The final Cox model for RSV DC was adjusted for age at enrollment, sex, maternal history of asthma, parental history of eczema, prenatal smoke exposure, infant history of eczema, history of daycare attendance, and intensive care at baseline. Age and intensive care were obtained from medical record abstraction; other covariates were parent reported.

We assessed the possibility of effect modification by the viral etiology of bronchiolitis at hospitalization. We fit a Cox proportional hazards model with an interaction term for virus at hospitalization (RSV infection with vs without RV coinfection) and RSV DC, and main effects for both variables. Interaction models were stratified by age at enrollment but did not adjust for other variables due to small counts in some categories.

RV DC analyses were restricted to infants with RV infection at the index hospitalization. Due to the smaller sample size in this analysis, we fit a parsimonious model adjusted for age at enrollment, parental history of eczema, and intensive care at baseline.

Sequential Infection

RSV SI was not analyzed as an exposure variable due to small sample size (n = 3). All infants with clearance swab data were included in the RV SI analysis because all infants, regardless of their viral infection upon hospitalization, were eligible for this outcome. We analyzed RV SI using the same statistical methods used for RSV DC.

Similar to RSV DC, we assessed the possibility of effect modification by viral etiology of bronchiolitis at baseline. We fit a Cox proportional hazards model with interaction terms for virus at hospitalization and RV SI, and main effects for all variables. Virus at hospitalization was categorized as RSV (without RV coinfection); RV (without RSV coinfection); RSV-RV coinfection; or non-RSV, non-RV viral etiology. Postestimation Wald tests were used for pairwise comparisons of interest.

To assess the potential for sparse data bias [19], we reclassified 1 participant from the highest-risk exposure category to the referent category and fit the model again. This process was repeated for each participant in the smallest exposure category (RV [without RSV coinfection] at hospitalization and RV SI) who developed recurrent wheezing.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 14.1 (StataCorp). Models accounted for potential clustering by site using a clustered sandwich estimator. A 2-sided α level of .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Overall, 921 infants were followed longitudinally. Clearance swabs from 673 infants were collected approximately 3 weeks after the hospitalization NPA (median 21 days; interquartile range [IQR], 20–24). The analytic cohort (n = 673 infants with a clearance nasal swab) was similar to the nonanalytic cohort (n = 248 infants without a clearance nasal swab) in age, sex, parental history of atopic conditions, and preterm birth (Supplementary Table 1). The analytic cohort had a higher proportion of non-Hispanic white infants (50% vs 25%) and infants with private health insurance (48% vs 22%). Infants in the analytic cohort were less likely to have a history of eczema (13% vs 19%) or prenatal smoke exposure (12% vs 18%). In the analytic cohort, the median age at baseline was 3 months (IQR, 2–6), 59% were male, 18% were non-Hispanic black, and 27% were Hispanic. The survivor functions for development of recurrent wheezing did not differ significantly between the analytic and nonanalytic cohort (P = .27).

Delayed Clearance

Respiratory Syncytial Virus Delayed Clearance

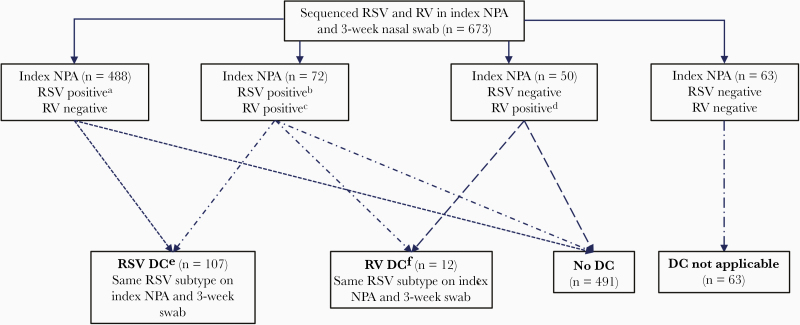

Among 560 infants with RSV at hospitalization, 107 (19%) had RSV DC, which consisted of RSV-A DC (n = 81) and RSV-B DC (n = 26) (Figure 1). As reported previously [11], younger participants and those with parental history of eczema were more likely to have RSV DC. The prevalence of symptoms at the time of clearance swab collection did not differ significantly by RSV DC status (57% among children without RSV DC vs 50% among children with RSV DC; P = .18).

Figure 1.

Identification of infants with delayed clearance of respiratory syncytial virus or rhinovirus after bronchiolitis hospitalization. Abbreviations: DC, delayed clearance; NPA, nasopharyngeal aspirate; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus. aRSV-A (n = 361), RSV-B (n = 125), RSV-A and RSV-B (n = 2). bRSV-A (n = 50), RSV-B (n = 21), RSV-A and RSV-B (n = 1). cRV-A (n = 37), RV-B (n = 6), RV-C (n = 26), RV-A and RV-B (n = 1), RV-A and RV-C (n = 1), RV-B and RV-C (n = 1). dRV-A (n = 22), RV-B (n = 1), RV-C (n = 25), RV-A and RV-C (n = 1), RV-B and RV-C (n = 1). eRSV-A (n = 81) and RSV-B (n = 26). fRV-A (n = 7), RV-B (n = 2), RV-C (n = 2), RV-A and RV-C (n = 1).

RSV DC was not associated with recurrent wheezing in the unadjusted or adjusted model (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.02; 95% confidence interval [CI], .74–1.41; P = .91; Table 1). Results were unchanged after further adjustment for preterm birth (32–37 vs >37 weeks) (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, .73–1.41; P = .93). The cumulative incidence curves for recurrent wheezing were similar in infants with vs without RSV DC (Supplementary Figure 2). The association between RSV DC and recurrent wheezing did not differ by virus at hospitalization (RSV infection with vs without RV coinfection) (Pinteraction = .58; Supplementary Figure 3).

Table 1.

Associations of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Delayed Clearance and Rhinovirus Delayed Clearance With Recurrent Wheezing From Cox Proportional Hazards Models

| Unadjusted Model Results | Adjusted Model Results, Exposure: RSV DC | Adjusted Model Results, Exposure: RV DC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSV at Hospitalization (n = 560) | RSV at Hospitalization (n = 560) | RV at Hospitalization (n = 122) | |||||||

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

| Exposures | |||||||||

| RSV DC | 0.89 | .64–1.23 | .47 | 1.02 | .74–1.41 | .91 | … | … | … |

| RV DCa | 1.01 | .42–2.44 | .99 | … | … | … | 1.08 | .44–2.62 | .87 |

| Characteristics at enrollment | |||||||||

| Age, mo | 2.17 | 1.43–3.31 | <.001 | Adjusted via stratificationb | Adjusted via stratificationb | ||||

| Male sex | 0.91 | .69–1.19 | .49 | 1.00 | .75–1.34 | .98 | … | … | … |

| Maternal history of asthma | 1.60 | 1.06–2.42 | .03 | 1.29 | .81–2.05 | .28 | … | … | … |

| Parental history of eczema | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.76 | 1.31–2.36 | <.001 | 1.67 | 1.18–2.35 | .004 | 2.14 | 1.07–4.29 | .03 |

| No | 1.00 | Ref | 1.00 | Ref | 1.00 | Ref | |||

| Unknown | 1.49 | .87–2.54 | .15 | 1.45 | .79–2.65 | .23 | 1.89 | .71–5.02 | .20 |

| Prenatal smoke exposure | 1.63 | 1.07–2.48 | .02 | 1.55 | .98–2.44 | .06 | … | … | … |

| History of eczema | 1.60 | 1.12–2.28 | .01 | 1.16 | .79–1.69 | .45 | … | … | … |

| Ever attended daycare | 1.39 | 1.15–1.69 | .001 | 1.10 | .83–1.45 | .50 | … | … | … |

| Course during hospitalization for bronchiolitis | |||||||||

| Intensive care usec | 1.14 | .79–1.63 | .49 | 1.47 | .98–2.19 | .06 | 0.94 | .52–1.72 | .85 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DC, delayed clearance; HR, hazard ratio; Ref, reference; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus.

aModel was limited to participants with RV at hospitalization (n = 122) irrespective of RSV at hospitalization.

bAdjusted for age at enrollment (<2 mo vs ≥2 mo) via stratification.

cDefined as admission to intensive care unit and/or use of mechanical ventilation (continuous positive airway pressure and/or intubation during inpatient stay, regardless of location) at any time during the hospitalization.

Rhinovirus Delayed Clearance

Among 122 participants with RV at hospitalization, 12/122 (10%) had RV DC, which consisted of RV-A DC (n = 8), RV-B DC (n = 2), and RV-C DC (n = 2). RV DC was not associated with recurrent wheezing in the unadjusted or adjusted model (Table 1).

Sequential Infection

Respiratory Syncytial Virus Sequential Infection

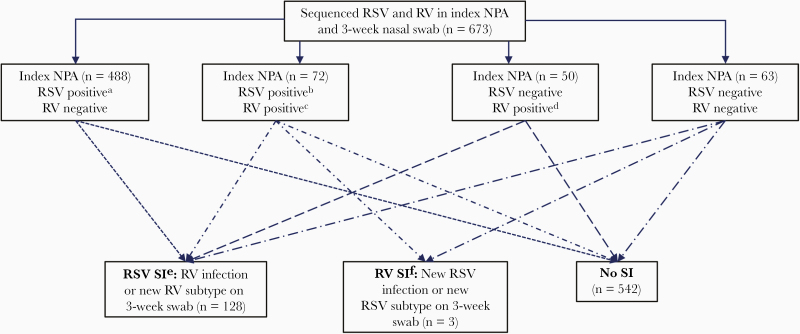

RSV SI was rare (3/673, 0.4%); we did not further analyze this exposure due to the small number.

Rhinovirus Sequential Infection

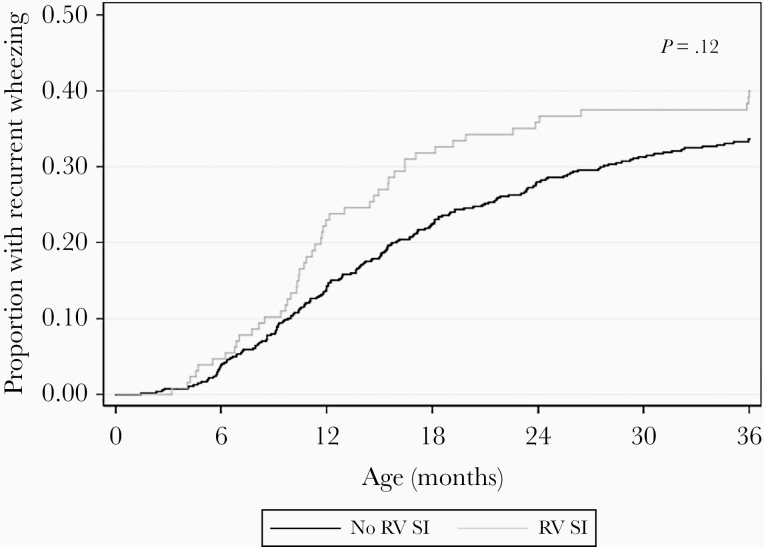

The prevalence of RV SI was 128/673 (19%) (Figure 2). Among the 128 infants with RV SI, most had no RV at hospitalization (n = 105) and then had RV-A (n = 59) or RV-C (n = 48) on the clearance swab. Factors associated with RV SI included older age, male sex, and history of daycare attendance (Table 2). At the time of clearance swab collection, children with RV SI were more likely to have symptoms compared to those without RV SI (73% vs 53%, P < .001). In particular, cough and runny nose were more prevalent among children with RV SI (both P < .001). The unadjusted association of RV SI with recurrent wheezing was HR 1.29 (95% CI, .96–1.72; P = .09; Table 3). In the adjusted model, RV SI was nonsignificantly associated with recurrent wheezing (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, .95–1.80; P = .10). Results were unchanged after further adjustment for preterm birth (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, .95–1.82; P = .10). The cumulative incidence curves for recurrent wheezing diverged around age 10 months (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Identification of infants with sequential infection with respiratory syncytial virus or rhinovirus after bronchiolitis hospitalization. Abbreviations: NPA, nasopharyngeal aspirate; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus; SI, sequential infection. aRSV-A (n = 361), RSV-B (n = 125), RSV-A and RSV-B (n = 2). bRSV-A (n = 50), RSV-B (n = 21), RSV-A and RSV-B (n = 1). cRV-A (n = 37), RV-B (n = 6), RV-C (n = 26), RV-A and RV-B (n = 1), RV-A and RV-C (n = 1), RV-B and RV-C (n = 1). dRV-A (n = 22), RV-B (n = 1), RV-C (n = 25), RV-A and RV-C (n = 1), RV-B and RV-C (n = 1). eRV-A (n = 72), RV-B (n = 2), RV-C (n = 49), RV-A and RV-C (n = 4), RV-B and RV-C (n = 1). fRSV-A (n = 3).

Table 2.

Factors Associated With Rhinovirus Sequential Infection Among Infants Hospitalized for Bronchiolitis

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 673), n (%) | No SI (n = 545), n (%) | SI (n = 128), n (%) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics at enrollment | ||||

| Age, mo, median (IQR) | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) | 4 (2–7) | .004 |

| Male sex | 397 (59) | 310 (57) | 87 (68) | .02 |

| Race/ethnicity | .73 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 339 (50) | 278 (51) | 61 (48) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 123 (18) | 98 (18) | 25 (20) | |

| Hispanic | 182 (27) | 144 (26) | 38 (27) | |

| Other | 29 (4) | 25 (5) | 4 (3) | |

| Insurance | .06 | |||

| Nonprivate or none | 345 (52) | 269 (50) | 76 (59) | |

| Private | 318 (48) | 266 (50) | 52 (41) | |

| Maternal history of asthma | 136 (20) | 113 (21) | 23 (18) | .50 |

| Parental history of eczema | .38 | |||

| Yes | 122 (18) | 104 (19) | 18 (14) | |

| No | 516 (77) | 414 (76) | 102 (80) | |

| Unknown | 35 (5) | 27 (5) | 8 (6) | |

| Estimated median annual household income by ZIP codeb | .49 | |||

| <$40 000 | 208 (31) | 163 (30) | 45 (35) | |

| $40 000–$79 999 | 375 (56) | 307 (56) | 68 (53) | |

| ≥$80 000 | 90 (13) | 75 (14) | 15 (12) | |

| Prenatal smoke exposure | 82 (12) | 65 (12) | 17 (13) | .71 |

| Postnatal smoke exposure | 92 (14) | 76 (14) | 16 (13) | .67 |

| Cesarean delivery | 237 (36) | 194 (36) | 43 (34) | .66 |

| Preterm birth 32–37 wk | 120 (18) | 102 (19) | 18 (14) | .22 |

| History of eczema | 90 (13) | 72 (13) | 18 (14) | .77 |

| Ever attended daycare | 145 (22) | 105 (19) | 42 (33) | <.001 |

| Household sibling | 527 (78) | 427 (78) | 100 (78) | .96 |

| Primarily breastfed during age 0–3 mo | 341 (52) | 276 (52) | 65 (52) | .92 |

| Course during hospitalization for bronchiolitis | ||||

| Symptom onset within 24 h of presentation | 127 (19) | 107 (20) | 20 (16) | .30 |

| Intensive care usec | 102 (15) | 89 (16) | 13 (10) | .08 |

| Hospital length of stay, d, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | .41 |

| Laboratory testing | ||||

| Virology | .02 | |||

| RSV (no RV coinfection) | 488 (73) | 404 (74) | 84 (66) | |

| RV (no RSV coinfection) | 50 (7) | 42 (8) | 8 (6) | |

| RSV-RV coinfection | 72 (11) | 57 (10) | 15 (12) | |

| Non-RSV, non-RV | 63 (9) | 42 (8) | 21 (16) | |

| Blood eosinophilia (≥4%) | .65 | |||

| Yes | 59 (9) | 50 (9) | 9 (7) | |

| No | 530 (79) | 429 (79) | 101 (79) | |

| Missing | 84 (12) | 66 (12) | 18 (14) | |

| 3 weeks post hospitalization | ||||

| RSV delayed clearance | 107 (19) | 103 (22) | 4 (4) | <.001 |

| Presence of symptomsd | 371 (57) | 279 (53) | 92 (73) | <.001 |

| Cough | 245 (38) | 180 (34) | 65 (52) | <.001 |

| Runny nose | 242 (37) | 170 (32) | 72 (58) | <.001 |

| Fever | 15 (2) | 11 (2) | 4 (3) | .51 |

| Hoarse | 63 (10) | 48 (9) | 15 (12) | .35 |

| Tachypnea | 58 (9) | 41 (8) | 17 (13) | .04 |

| Wheezing | 88 (14) | 65 (12) | 23 (18) | .08 |

| Retractions | 44 (7) | 35 (7) | 9 (7) | .85 |

| Cyanosis | 2 (0) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Apnea | 3 (0) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

Results are number (percent) of infants unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus; SI, sequential infection.

a P values are from χ2 tests, Fisher exact tests, or Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate.

bMedian household income by ZIP code was estimated by linking parent-reported home ZIP codes at enrollment to median household income estimates from Esri Business Analyst Desktop.

cDefined as admission to intensive care unit and/or use of mechanical ventilation (continuous positive airway pressure and/or intubation during inpatient stay, regardless of location) at any time during the hospitalization.

dSymptoms were assessed by parents at the time of nasal swab collection. Data were available for n = 652.

Table 3.

Associations of Rhinovirus Sequential Infection With Recurrent Wheezing From Unadjusted and Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Models (n = 673)

| Unadjusted Model Results | Adjusted Model Results, Exposure: RV SI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

| Exposure | ||||||

| RV SI | 1.29 | .96–1.72 | .09 | 1.31 | .95–1.80 | .10 |

| Characteristics at enrollment | ||||||

| Age, mo | 1.75 | 1.25–2.45 | .001 | Adjusted via stratificationa | ||

| Male sex | 0.96 | .74–1.24 | .74 | 1.03 | .79–1.33 | .84 |

| Maternal history of asthma | 1.69 | 1.23–2.32 | .001 | 1.38 | .93–2.05 | .11 |

| Parental history of eczema | ||||||

| Yes | 1.95 | 1.49–2.56 | <.001 | 1.83 | 1.41–2.38 | <.001 |

| No | 1.00 | Ref | 1.00 | Ref | ||

| Unknown | 1.39 | .81–2.37 | .23 | 1.32 | .72–2.41 | .37 |

| Prenatal smoke exposure | 1.48 | 1.00–2.18 | .049 | 1.45 | .98–2.12 | .06 |

| History of eczema | 1.65 | 1.21–2.24 | .001 | 1.21 | .85–1.72 | .29 |

| Ever attended daycare | 1.38 | 1.15–1.66 | <.001 | 1.12 | .90–1.39 | .31 |

| Course during hospitalization for bronchiolitis | ||||||

| Intensive care useb | 1.12 | .91–1.38 | .28 | 1.37 | 1.09–1.72 | .008 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; Ref, reference; RV, rhinovirus; SI, sequential infection.

aAdjusted for age at enrollment (<2 mo vs ≥2 mo) via stratification.

bDefined as admission to intensive care unit and/or use of mechanical ventilation (continuous positive airway pressure and/or intubation during inpatient stay, regardless of location) at any time during the hospitalization.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence curves for development of recurrent wheezing by age 3 years, according to rhinovirus sequential infection (n = 673). P value is from log-rank test for equality of survivor functions. Abbreviations: RV, rhinovirus; SI, sequential infection.

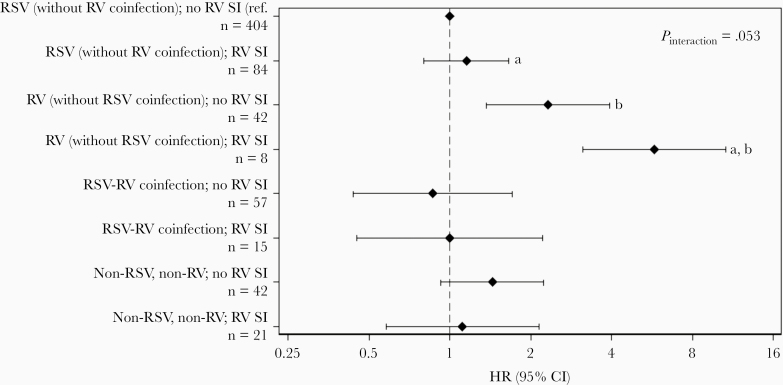

However, higher risk of recurrent wheezing was observed among the 8 children who had RV (without RSV coinfection) at hospitalization and RV SI (overall Pinteraction = .053; Figure 4). Postestimation Wald tests revealed that children with RV infection (without RSV coinfection) at hospitalization and RV SI had significantly higher risk of recurrent wheezing compared to children with RV (without RSV coinfection) at hospitalization and no RV SI (HR, 2.49; 95% CI, 1.22–5.06; P = .01), as well as children with RSV (without RV coinfection) at hospitalization and RV SI (HR, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.03–12.32; P < .001). Among children with RSV (without RV coinfection) at hospitalization, RV SI was not associated with increased risk of recurrent wheezing (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, .80–1.66; P = .44). The sensitivity analysis did not indicate sparse data bias, as hazard ratios in the highest-risk group of participants with recurrent wheezing remained in the range of 5.0–6.4 (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 4.

Hazard ratios for recurrent wheezing, by virus at hospitalization and rhinovirus sequential infection categories. Results were obtained using a Cox proportional hazards model with interaction terms for virus at hospitalization (categorized as RSV [without RV coinfection]; RV [without RSV coinfection]; RSV-RV coinfection; or non-RSV, non-RV viral etiology) and RV SI, as well as main effects for all variables. The marker and error bars represent the HR and 95% CI within each category; the referent category was RSV (without RV coinfection) at hospitalization and no RV SI. The model was stratified by age at enrollment (<2 mo vs ≥2 mo) but was not adjusted for other covariates. The interaction P value was calculated using a Wald test of the null hypothesis that the interaction coefficients all equal zero. Separate pairwise comparisons (a,b) were tested using postestimation Wald tests. aP < .001; bP = .01. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ref., reference; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus.

Discussion

In this planned secondary data analysis of the MARC-35 multicenter cohort of infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis, RSV DC and RV DC were not associated with recurrent wheezing by age 3 years. There were insufficient infants with RSV SI for analysis. RV SI was nonsignificantly associated with higher risk of recurrent wheezing. However, the association of RV SI with risk of recurrent wheezing differed by the viral etiology of bronchiolitis at hospitalization, with the highest risk observed among infants with RV (without RSV coinfection) at hospitalization followed by RV SI. These results confirm the important relation of RV severe bronchiolitis to recurrent wheezing, and extend this finding by demonstrating that infants with RV SI may be at particularly high risk of posthospitalization respiratory morbidity (ie, recurrent wheezing).

RSV is the most common viral infection associated with severe bronchiolitis [15]. Despite severe RSV bronchiolitis having a weaker association with recurrent wheezing than severe RV bronchiolitis [20], the high yearly population incidence of RSV bronchiolitis [1] makes RSV an important risk factor for recurrent wheezing and asthma [21]. Given the high population burden, there is a need to identify the subgroup of infants with severe RSV bronchiolitis at higher risk of recurrent wheezing and childhood asthma in order to target preventive strategies. In the present analysis, we found that the 19% of infants with RSV DC had no higher risk of recurrent wheezing than infants who cleared RSV within 3 weeks of hospitalization. It is also possible that the infant’s nasal microbiota may play a role in the development of recurrent wheezing [22], and recent evidence highlights that RSV-associated neutrophil responses modulate bacterial growth and influence the local nasopharyngeal ecology [23]. Thus, it remains important to continue examining the relation of RSV infection, microbiota, and host response to recurrent wheezing and asthma in order to identify the subgroup of infants with severe RSV bronchiolitis at higher risk of developing these chronic morbidities.

RV is the second most common viral infection associated with severe bronchiolitis [15] and has a stronger association with recurrent wheezing and childhood asthma than RSV [20]. Among the 122 infants with RV infection at hospitalization, 12 (10%) had RV DC (ie, the same genotype of RV weeks after hospitalization). These MARC-35 results build upon a study by Jartti and colleagues reporting delayed RV clearance in 1 of 8 infants (12%) with moderate to severe wheezing illnesses lasting ≥2 weeks [24]. Although the current study had limited statistical power, we found that—similar to RSV DC—the 12 infants with RV DC were not at higher risk of recurrent wheezing.

In contrast to the small number of infants with RV DC, there were 128 (19%) infants who had RV SI (ie, a new RV genotype 3 weeks after the first day of hospitalization). The present results mirror previous findings that RV detection in the weeks after hospitalization is more likely to be a new RV infection (ie, SI) [25] rather than RV DC [8, 26]. The relation of RV SI to wheezing was examined by Turunen and colleagues who found that children with a first wheezing episode due to RV-A or RV-C had a new RV-associated wheezing episode sooner than children who had their first wheezing episode due to a virus other than RV [27]. We have extended these findings, by showing that the relation of RV SI (mostly RV-A and RV-C) in infancy to recurrent wheezing by age 3 years differed by the virus at hospitalization. In other words, infants with RV (without RSV coinfection) at hospitalization followed by a different RV genotype weeks later had a significantly higher risk of recurrent wheezing than infants with RSV (without RV coinfection) at hospitalization followed by RV, and also infants with RV (without RSV coinfection) at hospitalization and no RV SI. Although the interpretation of these results must be tempered by the small number of infants with sequential RV infections and causality cannot be established, this finding suggests that recurrent wheezing may be related to an increased exposure to, frequency of, and/or susceptibility to RV infections (eg, allergic sensitization and polymorphism in CDHR3) [28–30].

It is also possible that children with asthma who have a high frequency of RV detection during acute asthma exacerbations may provide insights into the underlying pathobiology of the present risk group (ie, sequential RV infections), especially given the strong association between severe RV bronchiolitis and the development of childhood asthma [28]. In people with asthma, there can be impaired interferon induction [31], specifically interferon types I and III, which play a critical role in the host response to viral infections [32]. One potential mechanism for this impairment may be deficient pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which detect viruses and initiate the innate immune response [33]. Indeed, Deschildre and colleagues found altered PRR function in the subgroup of children with asthma who had SI, which were mostly RV [34].

Although the aforementioned mechanisms are possible, the pathobiology of RV SI in children with asthma may neither translate to infants with RV SI bronchiolitis nor explain the present findings. Although the number of patients with RV SI was small and replication is needed, it is unclear why infants with severe RV bronchiolitis followed by a new RV infection have a higher risk of recurrent wheezing compared with infants who have severe RSV bronchiolitis followed by RV. Another mechanistic possibility may be the different underlying pathobiology of RSV and RV infections in infants with severe bronchiolitis. RSV and RV infections at hospitalization are associated with different nasopharyngeal and serum metabolites [35, 36], have distinct immune responses [37], and different associated nasopharyngeal microbiota [38]. These differences in pathobiology by infecting virus at hospitalization may explain the differences in chronic respiratory morbidity. In future work, our group will compare the host responses in children with and without DC or SI while accounting for age, atopy, and the microbiome. We will also repeat the present analyses when the children turn age 6 years and are formally evaluated for asthma. Furthermore, even though the present association between RV SI and recurrent wheezing is based on a small number of patients, we hope these results encourage further research and hypothesis generation on sequential RV infections in infants with severe bronchiolitis or other populations who may be susceptible to repeated RV infections.

This study has several potential limitations. First, RV can be detected in up to 40% of asymptomatic infants [24]. However, all infants in the MARC-35 cohort were symptomatic at hospitalization and transcriptional profiling has demonstrated that symptomatic RV infections induce a robust host response [39]. In addition, while asymptomatic infection was possible weeks after hospitalization, RV detection in the clearance swab was clinically relevant as demonstrated in the present analysis by the increased frequency of symptoms and risk of recurrent wheezing in infants with RV infection at 3 weeks. Second, the study population was hospitalized infants and the RV SI risk group may not be generalizable to infants with less severe bronchiolitis. Third, we collected samples at only 2 time points and, as such, may have missed different timing of SI that would also be of clinical relevance. Fourth, we collected NPAs at hospitalization and nasal swabs at clearance. However, these 2 collection methods have been shown to yield comparable results [40]. Fifth, our study may have been underpowered to detect a statistically significant association of RV SI with risk of recurrent wheezing at the P < .05 level. Finally, the present analysis did not account for potential genetic differences within our cohort, which may place children at higher risk of RV infections and/or recurrent wheezing [28]. We are currently pursuing this important research question.

In summary, we found in this large, prospective, multicenter study of infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis that RSV DC and RV DC were not associated with increased risk for recurrent wheezing. Additionally, we found that the relation of RV SI to recurrent wheezing differed by the viral infection at hospitalization. Specifically, infants with RV bronchiolitis at hospitalization followed by a different RV genotype infection weeks after discharge had a higher risk of recurrent wheezing than either infants with RV infection only at hospitalization or infants with RSV infection at hospitalization followed by RV. Although the SI findings require replication, these results support further investigation examining potential differences in underlying genetics and host immune responses in infants who may be more susceptible to repeated RV infections, and thus recurrent wheezing and later asthma exacerbations.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgment. We thank the MARC-35 study hospitals and research personnel for their ongoing dedication to bronchiolitis and asthma research.

Disclaimer. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (grant numbers U01 AI-087881, R01 AI-114552, R01 AI-108588, and R21 HL-129909).

Potential conflicts of interest. P. A. P. provided bronchiolitis-related consultation for Gilead, Novavax, and Regeneron. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Brown DF, Mansbach JM, CamargoCA, Jr. Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States, 2000–2009. Pediatrics 2013; 132:28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dumas O, Hasegawa K, Mansbach JM, Sullivan AF, Piedra PA, CamargoCA, Jr. Severe bronchiolitis profiles and risk of recurrent wheeze by age 3 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 143:1371–9.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomsen SF, van der Sluis S, Stensballe LG, et al. Exploring the association between severe respiratory syncytial virus infection and asthma: a registry-based twin study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 179:1091–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koponen P, Helminen M, Paassilta M, Luukkaala T, Korppi M. Preschool asthma after bronchiolitis in infancy. Eur Respir J 2012; 39:76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sigurs N, Gustafsson PM, Bjarnason R, et al. Severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy and asthma and allergy at age 13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171:137–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bacharier LB, Cohen R, Schweiger T, et al. Determinants of asthma after severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 130:91–100.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ad hoc Statement Committee, American Thoracic Society. Mechanisms and limits of induced postnatal lung growth. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170:319–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wood LG, Powell H, Grissell TV, et al. Persistence of rhinovirus RNA and IP-10 gene expression after acute asthma. Respirology 2011; 16:291–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilkinson TM, Donaldson GC, Johnston SL, Openshaw PJ, Wedzicha JA. Respiratory syncytial virus, airway inflammation, and FEV1 decline in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173:871–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gern JE, Rosenthal LA, Sorkness RL, LemanskeRF, Jr. Effects of viral respiratory infections on lung development and childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005; 115:668–74; quiz 675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mansbach JM, Hasegawa K, Piedra PA, et al. Haemophilus-dominant nasopharyngeal microbiota is associated with delayed clearance of respiratory syncytial virus in infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis 2019; 219:1804–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hasegawa K, Mansbach JM, Ajami NJ, et al. ; the MARC-35 Investigators Association of nasopharyngeal microbiota profiles with bronchiolitis severity in infants hospitalised for bronchiolitis. Eur Respir J 2016; 48:1329–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al. ; American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2014; 134:e1474–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mansbach JM, Clark S, Piedra PA, et al. ; MARC-30 Investigators Hospital course and discharge criteria for children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. J Hosp Med 2015; 10:205–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Teach SJ, et al. ; MARC-30 Investigators Prospective multicenter study of viral etiology and hospital length of stay in children with severe bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012; 166:700–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bochkov YA, Grindle K, Vang F, Evans MD, Gern JE. Improved molecular typing assay for rhinovirus species A, B, and C. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:2461–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120:S94–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mansbach JM, Hasegawa K, Geller RJ, Espinola JA, Sullivan AF, Camargo CA Jr; MARC-35 Investigators Bronchiolitis severity is related to recurrent wheezing by age 3 years in a prospective, multicenter cohort. Pediatr Res 2020; 87:428–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Greenland S, Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Sparse data bias: a problem hiding in plain sight. BMJ 2016; 352:i1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hasegawa K, Mansbach JM, Bochkov YA, et al. Association of rhinovirus C bronchiolitis and immunoglobulin E sensitization during infancy with development of recurrent wheeze. JAMA Pediatr 2019; 173:544–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hasegawa K, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA Jr. Infectious pathogens and bronchiolitis outcomes. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014; 12:817–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mansbach JM, Luna PN, Shaw CA, et al. Increased Moraxella and Streptococcus species abundance after severe bronchiolitis is associated with recurrent wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145:518–27.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sande CJ, Njunge JM, Mwongeli Ngoi J, et al. Airway response to respiratory syncytial virus has incidental antibacterial effects. Nat Commun 2019; 10:2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jartti T, Lee WM, Pappas T, Evans M, Lemanske RF Jr, Gern JE. Serial viral infections in infants with recurrent respiratory illnesses. Eur Respir J 2008; 32:314–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Engelmann I, Mordacq C, Gosset P, et al. Rhinovirus and asthma: reinfection, not persistence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188:1165–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kling S, Donninger H, Williams Z, et al. Persistence of rhinovirus RNA after asthma exacerbation in children. Clin Exp Allergy 2005; 35:672–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Turunen R, Vuorinen T, Bochkov Y, Gern J, Jartti T. Clinical and virus surveillance after the first wheezing episode: special reference to rhinovirus A and C species. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2017; 36:539–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jartti T, Gern JE. Role of viral infections in the development and exacerbation of asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140:895–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lamborn IT, Jing H, Zhang Y, et al. Recurrent rhinovirus infections in a child with inherited MDA5 deficiency. J Exp Med 2017; 214:1949–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Esquivel A, Busse WW, Calatroni A, et al. Effects of omalizumab on rhinovirus infections, illnesses, and exacerbations of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196:985–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Contoli M, Message SD, Laza-Stanca V, et al. Role of deficient type III interferon-lambda production in asthma exacerbations. Nat Med 2006; 12:1023–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yoo JK, Kim TS, Hufford MM, Braciale TJ. Viral infection of the lung: host response and sequelae. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132:1263–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 2006; 124:783–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Deschildre A, Pichavant M, Engelmann I, et al. Virus-triggered exacerbation in allergic asthmatic children: neutrophilic airway inflammation and alteration of virus sensors characterize a subgroup of patients. Respir Res 2017; 18:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stewart CJ, Hasegawa K, Wong MC, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus bronchiolitis are associated with distinct metabolic pathways. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:1160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stewart CJ, Mansbach JM, Piedra PA, Toivonen L, Camargo CA, Hasegawa K. Association of respiratory viruses with serum metabolome in infants with severe bronchiolitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2019; 30:848–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Heinonen S, Rodriguez-Fernandez R, Diaz A, Oliva Rodriguez-Pastor S, Ramilo O, Mejias A. Infant immune response to respiratory viral infections. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2019; 39:361–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mansbach JM, Hasegawa K, Henke DM, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus severe bronchiolitis are associated with distinct nasopharyngeal microbiota. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137:1909–13.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heinonen S, Jartti T, Garcia C, et al. Rhinovirus detection in symptomatic and asymptomatic children: value of host transcriptome analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193:772–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hansen KB, Westin J, Andersson LM, Lindh M, Widell A, Nilsson AC. Flocked nasal swab versus nasopharyngeal aspirate in adult emergency room patients: similar multiplex PCR respiratory pathogen results and patient discomfort. Infect Dis (Lond) 2016; 48:246–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.