Abstract

Aim:

To classify the association between the maternal lipidome and DNA methylation in cord blood leukocytes.

Materials & methods:

Untargeted lipidomics was performed on first trimester maternal plasma (M1) and delivery maternal plasma (M3) in 100 mothers from the Michigan Mother-Infant Pairs cohort. Cord blood leukocyte DNA methylation was profiled using the Infinium EPIC bead array and empirical Bayes modeling identified differential DNA methylation related to maternal lipid groups.

Results:

M3-saturated lysophosphatidylcholine was associated with 45 differentially methylated loci and M3-saturated lysophosphatidylethanolamine was associated with 18 differentially methylated loci. Biological pathways enriched among differentially methylated loci by M3 saturated lysophosphatidylcholines were related to cell proliferation and growth.

Conclusion:

The maternal lipidome may be influential in establishing the infant epigenome.

Keywords: : developmental epigenetics, DNA methylation, epigenome-wide association studies, lipidomics, lysophospholipids, pregnancy, umbilical cord blood

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) theory postulates that insults during early life can permanently program the fetus/offspring, influencing long-term health outcomes [1]. Changes in the maternal metabolome across gestation occur to support the developing needs of the fetus [2] and are influenced by maternal characteristics such as obesity [3–5] and dietary intake [6]. Fluctuations in the maternal metabolome have the potential to influence development through altering DNA methylation levels in the fetus, shifting the developmental trajectory of the offspring via epigenetic programming and culminating in structural changes in fetal organs and tissues to adapt to the intrauterine environment and prepare for the external environment [7]. Profiling the maternal metabolome and lipidome, the low-molecular weight lipid intermediates in metabolism, and relating to offspring epigenome provides an objective view of maternal nutrient availability during pregnancy and its relationship with the infant epigenome.

Our previous studies relating the maternal lipidome with the infant lipidome [8] documented selective transport of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and lysophospholipids (LysoPL) across the placenta into the umbilical cord blood (CB) to support fetal development. Additionally, infant lipid groups containing PUFAs and LysoPLs were associated with birth weight, a common outcome in DOHaD studies due to its association with cardiometabolic disease in adulthood [9,10]. We identified that maternal PUFAs in early gestation were vital for the establishment of umbilical CB lipids associated with birth weight, and here we further investigate their association with infant DNA methylation.

Epigenetics is defined as mitotically heritable changes in gene expression that occur without altering the DNA sequence, and there is growing evidence that epigenetic mechanisms are an important contributor to developmental programming [11]. The most extensively studied epigenetic modification is DNA methylation at CpG sites, sequences of cytosine and guanine connected by a phosphate group. Across a variety of human cell types, 70% of CpG sites are consistently methylated [12]. Regions in the genome with high CpG site frequency are called CpG islands and are often located at gene promoters. Previous studies found umbilical CB DNA methylation to be associated with maternal dietary intake [13], maternal pre pregnancy BMI [14], and infant birth weight [15].

Previous work from our group [16] provided some of the first evidence for a relationship between specific metabolites in the maternal plasma with DNA methylation in umbilical CB leukocytes. DNA methylation at genes associated with lipid metabolism and growth, including ESR1, PPARα, IGF2 and H19, was correlated with maternal essential fatty acids (FA) and acylcarnitines measured during first trimester and at term. A recent study [17] assessing how the maternal lipidome at approximately 26 weeks gestation influences DNA methylation in umbilical CB cells using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 (450K) assay found that maternal phospholipids and LysoPLs were associated with offspring DNA methylation, suggesting the importance of that lipid fraction in establishing methylation patterns. The objective of the present study is to gain a deeper understanding of how the maternal lipidome at early gestation and delivery is related to altered DNA methylation patterns in umbilical CB leukocytes by assessing associations between 573 maternal plasma lipids profiled with high-throughput shotgun lipidomics and genome-wide infant CB DNA methylation profiles.

Materials & methods

Study population

All study procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Medical School (MI, USA) Institutional Review Board (HUM00017941). All adult participants provided written informed consent, and all clinical and biological samples were deidentified prior to analysis.

Biological samples were obtained from women and their offspring enrolled in the Michigan Mother Infant Pairs (MMIP) cohort (2010–present), an ongoing birth cohort study at the University of Michigan. Recruitment of women took place during their initial prenatal appointment, between 8 and 14 weeks of gestation. Eligibility criteria include women ages 18–42 years, a spontaneously conceived singleton pregnancy, and intention to deliver at the UM Hospital. Inclusion criteria for the current study include completed demographic, survey and health information at the initial study visit and availability of all biospecimen for metabolomics and epigenomics analyses (n = 100).

During the initial study visit, participants provided a blood sample (M1). Anthropometry information (weight and height) was obtained from medical records to calculate an estimated baseline BMI at M1. Maternal venous blood samples (M3) were collected upon admittance at UM Hospital for delivery, and CB samples were collected via venipuncture from the umbilical cord. Women were not required to be fasted for the blood sampling. All mother-infant dyads met additional inclusion criteria for this study, including infant birth weight greater than 2500 g and maternal BMI greater than 18.5 kg/m2. Previous work in the MMIP cohort assessed the relationship between targeted metabolites in maternal plasma and DNA methylation in genes associated with lipid metabolism and growth [16] and the impact of prenatal toxicant exposure, such as bisphenol A, on maternal and neonatal inflammasome [18], oxidative stress markers [19] and fetal growth [20]. All participants were included in previously published work in the MMIP cohort assessing the relationship between the maternal and infant CB lipidome [8].

Lipidomics profiling

Untargeted shotgun lipidomics was performed as previously detailed [21], using reconstituted lipid extract from M1, M3 and CB plasma samples. Samples were ionized in positive and negative ionization model using a Triple TOF 5600 (AB Sciex, Ontario Canada). Chromatographic peaks that represent features are detected using a modified version of existing commercial software (Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis, CA, USA). Pooled human plasma samples and pooled experimental samples were included for quality control and batch normalization [22]. Detected features were excluded with a relative standard deviation greater than 40% in the pooled samples and/or less than 70% presence in the samples. Missing data were imputed using the K-nearest neighbor method.

Lipids were classified using LIPIDBLAST, a computer generated tandem mass spectral library containing 119,200 compounds from 26 lipid classes [23]. After processing, 573 lipids from multiple lipid classes were identified (Table 1). All lipids will be presented with the nomenclature as X:Y, where X is the length of the carbon chain and Y, the number of double bonds.

Table 1. . Lipid species class, abbreviation and number of lipids annotated from lipidomics analysis.

| Lipid class | Abbreviation | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Acylcarnitine | AC | 6 |

| Ceramide | CER | 51 |

| Cholesteryl ester | CE | 13 |

| Diacylglycerol | DG | 30 |

| Free fatty acid | FFA | 16 |

| Glucosylceramidase | GlcCer | 9 |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine | LysoPC | 29 |

| Lysophosphatidylethanolamine | LysoPE | 9 |

| Phosphatidic acid | PA | 4 |

| Phosphatidylcholine | PC | 96 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | PE | 44 |

| Plasmenyl-phosphatidylcholine | PL-PC | 54 |

| Plasmenyl-phosphatidylethanolamine | PL-PE | 36 |

| Phosphatidylglycerol | PG | 8 |

| Phosphatidylinositol | PI | 12 |

| Phosphatidylserine | PS | 2 |

| Sphingomyelin | SM | 65 |

| Triacylglycerol | TG | 97 |

DNA extraction

At the time of birth, infant umbilical CB was collected into PaxGene Blood DNA tubes (PreAnalytix, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland). Samples were stored at -80°C until extraction. DNA was extracted from infant CB leukocytes using the PaxGene Blood DNA kit, following standard protocols. At the University of Michigan Advanced Genomics Core, DNA concentration and integrity were quantified using a Qubit Fluorometer and extracts with a concentration greater than 15 ng/μl were selected for further analysis. Prior to DNA methylation analysis, approximately 500 ng of input DNA per sample underwent bisulfite conversion using the EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA).

Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis

DNA methylation analyses were performed by the University of Michigan Advanced Genomics Core. The Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC (EPIC) bead array was used to quantify DNA methylation at approximately 850,000 CpG sites (Illumina Inc, CA, USA), following standard protocols. The EPIC bead array quantifies at single-nucleotide resolution and contains probes that hybridize to loci throughout the genome located within CpG islands, genes, transcription binding sites, open chromatin regions and more. Umbilical CB samples were run in three experimental batches, which are considered in the statistical models [24].

DNA methylation data processing

Raw intensity probe data were processed using the Bioconductor minfi package 1.32.0 [25]. Probe data were converted into β values (between 0 and 1), representing the proportion methylated and calculated as β = [methylated/(methylated+unmethylated)]. Quality of samples and probes was determined by evaluating infant estimated sex (via methylation values on the X and Y chromosomes) versus known sex (as recorded in medical record) and detection and intensity of probe signals. Samples that failed quality check were removed from analysis (n = 1). Cross-reactive probes, probes with polymorphisms in the query site, poorly detected probes and probes located on X and Y chromosomes were excluded from this analysis [26]. After quality control, 804,108 probes were available for analysis. Normalization steps included dye bias correction, background correction and functional normalization [27]. β-values were converted logarithmically into M-values for statistical analysis. Although β-values are more intuitive for a biological interpretation, M-values are more valid for certain types of statistical models [28]. To estimate CB proportions of white blood cell types and nucleated red blood cells (nRBCs), we utilized an algorithm for Infinium data based on a CB reference dataset [24].

Statistical analysis

Creating lipid group scores

The lipidome is highly correlated due to lipids being metabolized by enzymes in a class-specific manner. For this analysis, the lipidome was grouped based on lipid class and the number of double bonds, yielding 41 groups (Supplementary Table 1). Lipid groups were scored for each mother-infant dyad using unsupervised Principal Component Analysis. The first principal component was retained, accounting for the largest portion of variance (PROC FACTOR, SAS 9.4, NC, USA). Within the principal component, each lipid received a factor loading, which is the correlation coefficient between the lipid and the component. Participant scores were created by multiplying the lipid factor loading by the lipid standardized peak intensity and adding together these values for all lipids within a lipid group (PROC SCORE, SAS 9.4, NC, USA). Lipid scores were considered outliers and removed if exceeding ±3 standard deviations from the mean score. While these values may be biologically relevant, including outliers into the analysis increases risk of false discovery, detecting CpG sites associated with participant variation, rather than the lipid group [29].

Identification of differentially methylated CpG sites & regions

This analysis sought to identify differential methylation in infant CB leukocytes associated with the maternal (M1 and M3) lipidome. Differentially methylated sites were classified fitting linear models using empirical Bayes methodology from the Bioconductor package limma, version 3.42.0 [30]. Covariates were selected for the final models that have evidence for confounding (i.e., associated with lipid groups and/or DNA methylation data). Singular value decomposition (SVD) analysis was used to identify covariates for the linear models that are associated with principal components of methylation [31] (Supplementary Figure 1). Variables considered were gestational weight gain, gestational age, maternal age, infant sex, cell type proportions and experimental factors (sample preparation plate, slide and array from the EPIC run). While all cell type proportions were associated with at least one principal component of DNA methylation (Supplementary Figure 1), the relationship between lipid groups and cell type proportions included very few significant correlations, even using an unadjusted p-value < 0.05 (data not shown). nRBCs and B-cells were included in the final statistical model as representative cell types since they were correlated with other cell types and associated with four components and the first component, respectively, of DNA methylation. In the SVD analysis, the experimental factor sample plate was associated with more variation in the DNA methylation principal components, compared with slide and array. Therefore, models were adjusted for sex, EPIC bead array sample plate and estimated proportions of nRBC and B-cells. Gestational age was not included in the model as there were no associations with DNA methylation principal components (Supplementary Figure 1), potentially due to the limited range of gestational age within our cohort (36 weeks and 6 days up to 41 weeks and 5 days). Results were adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing (number of CpG sites tested) using the Benjamini-Hochberg method with an FDR threshold for significance of 0.05 [32]. Differentially methylated regions (DMR) were identified by the R Bioconductor package DMRcate, version 2.0.0. All DMRs contained at least two CpG sites and were considered significant with an adjusted p-value threshold of 0.05 using the Stouffer’s method.

Path analysis

Biological pathways associated with differentially methylated genes were classified. To avoid bias when performing gene ontology with methylation data [33], we used the gometh function in the R package missMethyl, version 1.20.0 [34], to classify enriched KEGG [35] pathways. Pathway analysis was conducted separately for the following lipids groups with multiple significant CpG sites; M3 LysoPC-sat and LysoPE-sat. Differentially methylated CpG sites with an FDR <0.1 were selected to classify enriched biological pathways. Biological pathways were considered enriched with an FDR <0.05.

All analyses were performed using R software, version 3.5.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) unless otherwise noted. Figures were created using GraphPad Prism version 7.4 (CA, USA).

Results

Subject demographics

Maternal and infant population characteristics are reported in Table 2 (n = 100). Most women were between 30 and 34 years with an average baseline BMI of 25.9 ± kg/m2. Most newborns were delivered vaginally (72%). There was a similar distribution of birth weight in male and female newborns (n = 53 male, 47 female) with an average birth weight of approximately 3500 g. CB cell percentages estimated for CD4+T, CD8+T, B cells, granulocytes, monocytes, natural killer cells and nRBCs are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. . Characteristics of Michigan Mother Infant Pairs participants with lipidomics and neonatal DNA methylation data (n = 100 mother-infant pairs).

| Categorical variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age (years): | |

| 25–29 | 25 (25%) |

| 30–34 | 54 (54%) |

| 35–45 | 21 (21%) |

| Newborn sex: | |

| Males | 53 (53%) |

| Females | 47 (47%) |

| Delivery route: | |

| Vaginal | 72 (72%) |

| Caesarean | 28 (28%) |

| Continuous variables | Mean ± SD (n) |

| Maternal | |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 ± 6.1 (97) |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | 13.2 ± 5.3 |

| Newborn | |

| Gestational age (days) | 278 ± 7 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3504 ± 428 |

| Cord blood cell types (%): | |

| CD4+T | 15.3. ± 6.0 |

| CD8+T | 12.5 ± 3.8 |

| B cells | 8.6 ± 3.2 |

| Granulocytes | 47.9 ± 8.8 |

| Monocytes | 8.8 ± 2.5 |

| NK cells | 1.4 ± 3.0 |

| nRBC | 8.2 ± 4.9 |

CB cell type proportions were estimated using an algorithm for Infinium data based on a CB reference dataset [24].

CB: Cord blood; MMIP: Michigan Mother Infant Pairs; nRBC: Nucleated red blood cells.

Subject characteristics & DNA methylation

The relationship between population characteristics, CB cell type proportions and experimental factors (e.g., batch) with principal components of DNA methylation was explored using SVD analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). Our results indicate the lack of association between methylation components and maternal characteristics, including gestational weight gain, gestational age and maternal age. Infant sex was associated with component 2 (p < 1E-10) and component 3 (p < 0.01). Associations were observed between cell types and principal components, as the first component was associated with B cells (p < 0.01) and additional associations being observed with each other cell type. Technical covariates (slide, array and sample preparation plate) were associated with principal components, with consistent associations between sample plate and seven of the nine components. Results from SVD analysis informed covariate selection for the linear models.

Lipidomics analysis

Variations in the lipidomics profile between M1, M3 and CB are detailed in a previous manuscript [8]. Partial correlation networks were estimated between lipid groups at each time point. Multiple positive correlations were observed between lipid groups containing triacylglycerol, diacylglycerols and phospholipids; ceramides and sphingomyelins; plasmenyl-phosphatidylcholine and plasmenyl-phosphatidylethanolamine; and lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC) and lysophosphotidylethanolamine (LysoPE). Most positive correlations occurred between lipid groups containing lipids with similar number of double bonds.

Relationship between maternal lipid groups with DNA methylation in infant CB leukocytes

Table 3 lists the number of CpG sites significantly associated with maternal lipid groups (FDR <0.05), adjusting for infant sex, sample plate, nRBC (%) and B cells (%). Significant sites are shown stratified by ‘increased’ methylation and ‘decreased’ methylation with increasing lipids. The majority of differentially methylated CpG sites were associated with maternal delivery lipid groups. Genes annotated to these differentially methylated sites are reported in Table 4.

Table 3. . Number of significant differentially methylated CpG sites in umbilical cord blood leukocytes associated with maternal lipid groups.

| Lipid cluster | Maternal first trimester (M1) | Maternal term (M3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased | Increased | Decreased | Increased | |

| AcylCN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CE-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CER-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CER-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CER-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DG-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DG-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DG-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FFA-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FFA-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FFA-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GlcCer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LysoPC-sat | 0 | 1† | 2‡ | 43† |

| LysoPC-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LysoPC-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1† |

| LysoPE-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18† |

| LysoPE-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PC-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PC-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PC-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PE-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PE-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PE-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PG-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PG-mono | 0 | 3† | 0 | 0 |

| PI-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PI-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PI-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PLPC-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PLPC-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PLPC-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PLPE-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PLPE-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PLPE-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SM-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SM-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SM-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TG-sat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TG-mono | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TG-poly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Differentially methylated sites were classified fitting linear models using empirical Bayes methodology. Models were adjusted for sex, EPIC bead array sample plate, nRBC, and B cells. Results were adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method with an FDR threshold for significance of 0.05. Results reported as the number of CpG sites with significant differential methylation with M1 and M3 lipid groups. Significant site counts are stratified by “Increased” methylation (in red) and “Decreased” methylation (in green).

Red.

Green.

AC: Acylcarnitine; CE: Cholesterol ester; CER: Ceramide; DG: Diacylglycerol; FDR: False discovery rate; FFA: Free fatty acid; GluCer: Glucosylceramidase; LysoPC: Lysophosphatidylcholine; LysoPE: Lysophosphatidylethanolamine; nRBC: Nucleated red blood cells; mono: Monounsaturated; PC: Phosphatidylcholine; PE: Phosphatidylethanolamine; PG: Phosphatidylglycerol; PI: Phosphatidylinositol; PLPC: Plasmenyl-phosphatidylcholine; PLPE: Plasmenyl-phosphatidylethanolamine; poly: Polyunsaturated; sat: Saturated; SM: Sphingomyelin; TG: Triacylglycerol.

Table 4. . Genetic details of significant differentially methylated CpG sites in umbilical cord blood leukocytes associated with maternal lipid groups.

| Time point | Lipid group | CpG site | Chromosome | Gene | Relation to CpG Island | logFC | FDR p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | LysoPC sat M1 | cg07218192 | chr14 | MPP5 | N-Shore | 0.1196 | 0.0127 |

| M1 | PG mono M1 | cg24968215 | chr5 | PPARGC1B | Open Sea | 0.1717 | 0.0415 |

| M1 | PG mono M1 | cg14930059 | chr3 | TTC14 | Island | 0.1526 | 0.0415 |

| M1 | PG mono M1 | ch.19.23069863R | chr19 | Open Sea | 0.3117 | 0.0415 | |

| M3 | LysoPC poly M3 | cg01779447 | chr6 | IFITM4P | N-Shore | 0.1682 | 0.0122 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg15749322 | chr11 | ANKRD42 | Island | 0.3409 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg14103143 | chr17 | ATP5G1 | Island | 0.2758 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg21598517 | chr19 | B9D2 | Island | 0.1423 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg00598747 | chr19 | B9D2 | Island | 0.1547 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg19575351 | chr6 | C6orf141 | Island | 0.1247 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg01382153 | chr2 | CCDC108 | Island | 0.1795 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg11075121 | chr12 | COQ5 | S-Shore | 0.1683 | 0.0484 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg04410024 | chr8 | CRISPLD1 | Island | 0.1721 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg02325290 | chr2 | DBI | Island | 0.1483 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg01813748 | chr18 | DLGAP1-AS2 | Open Sea | 0.1760 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg12709907 | chr17 | EFTUD2 | Island | 0.1664 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg18071809 | chr19 | EID2B | Island | 0.1773 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg22045228 | chr2 | ELMOD3 | Island | 0.1951 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg01974100 | chr14 | FAM179B | N-Shore | 0.1529 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg11509404 | chr9 | GABBR2 | Island | 0.2466 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg07070542 | chr7 | GARS | Island | 0.1816 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg15485323 | chr6 | HIST1H1D | Open Sea | 0.1722 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg19060382 | chr12 | LOC253724 | S-Shore | 0.2293 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg17434483 | chr19 | LOC729991-MEF2B | S-Shore | 0.1403 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg25172519 | chr6 | MOXD1 | Island | 0.1668 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg17775912 | chr14 | MTHFD1 | Island | 0.1542 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg10326891 | chr4 | NUDT9 | Island | 0.2125 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg21001214 | chr12 | PA2G4 | Island | 0.2869 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg26431298 | chr1 | PRCC | Island | 0.2911 | 0.0496 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg17537899 | chr3 | RPL22L1 | S-Shore | 0.1982 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg22842064 | chr3 | RPL22L1 | Island | 0.1667 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg16696730 | chr21 | RSPH1 | Island | 0.2097 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg19049809 | chr17 | SFRS1 | S-Shore | 0.1779 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg22398523 | chr1 | SH3BP5L | Island | 0.1501 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg04696559 | chr5 | SKP2 | Island | 0.2191 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg23013931 | chr22 | SLC25A17 | N-Shore | 0.1928 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg23010414 | chr17 | SLFN5 | Island | 0.1801 | 0.0496 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg21151651 | chr11 | SPTY2D1 | Island | 0.2286 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg25781123 | chr3 | THUMPD3 | N-Shore | 0.3710 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg14210275 | chr17 | TMEM107 | Island | 0.1611 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg14345069 | chr4 | UFSP2 | Island | 0.1598 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg06356912 | chr3 | VILL | N-Shore | 0.2237 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg21665057 | chr3 | WDR53 | Island | 0.1210 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg22720041 | chr19 | ZNF229 | Island | 0.1516 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg13468174 | chr19 | ZNF584 | Island | 0.1577 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg17618194 | chr7 | ZNHIT1 | S-Shore | 0.2626 | 0.0471 |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | ch.16.79494380F | chr16 | Open Sea | 0.2426 | 0.0471 | |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg14205309 | chr11 | Open Sea | -0.1555 | 0.0471 | |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | ch.4.74730522R | chr4 | Open Sea | 0.1787 | 0.0471 | |

| M3 | LysoPC sat M3 | cg26809926 | chr7 | Open Sea | -0.1877 | 0.0471 | |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg08265188 | chr12 | ALG10 | Island | 0.5586 | 0.0338 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg22664986 | chr11 | ANKRD42 | Island | 0.2278 | 0.0364 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg12013332 | chr12 | BBS10 | Island | 0.2183 | 0.0338 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg12792102 | chr5 | BNIP1 | Open Sea | 0.2675 | 0.0364 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg19889500 | chr14 | DAD1 | N-Shore | 0.2409 | 0.0364 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg02325290 | chr2 | DBI | Island | 0.1488 | 0.0364 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg15485323 | chr6 | HIST1H1D | Open Sea | 0.1728 | 0.0364 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg16666115 | chr6 | MRPS18A | S-Shore | 0.1484 | 0.0338 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg16875280 | chr19 | OPA3 | N-Shore | 0.2928 | 0.0338 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg09367970 | chr12 | RAD51AP1 | Island | 0.1812 | 0.0338 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg04895581 | chr8 | RBM12B | Island | 0.2021 | 0.0372 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg05250654 | chr2 | RPS7 | Island | 0.2713 | 0.0364 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg16990505 | chr14 | SDCCAG1 | S-Shore | 0.1843 | 0.0364 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg23010414 | chr17 | SLFN5 | Island | 0.1969 | 0.0338 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg13045611 | chr17 | SUPT6H | S-Shore | 0.1908 | 0.0033 |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg23093590 | chr15 | Island | 0.2768 | 0.0338 | |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | cg07602492 | chr1 | S-Shore | 0.1654 | 0.0364 | |

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | ch.17.51385210R | chr17 | Open Sea | 0.1546 | 0.0364 |

FC: Fold change; FDR: False discovery rate; LysoPC: Lysophosphatidylcholine; LysoPE: Lysophosphatidylethanolamine; M1: Maternal first trimester; M3: Maternal term; mono: Monounsaturated; N-Shore: North shore; PG: Phosphatidylglycerol; poly: Polyunsaturated; sat: Saturated; S-Shore: South shore.

In M1, only a few lipid groups were associated with single-CpG site DNA methylation in CB leukocytes. Statistically significant associations were observed between M1 LysoPC-sat and a CpG site in MPP5 (log fold change = 0.12, probe ID cg07218192) (Table 4). Early gestation M1 PG-mono is positively associated with a CpG site in PPARGC1B (logFC = 0.17, probe ID cg24968215) and a CpG site in a CpG island of TTC14 (logFC = 0.15, probe ID cg14930059).

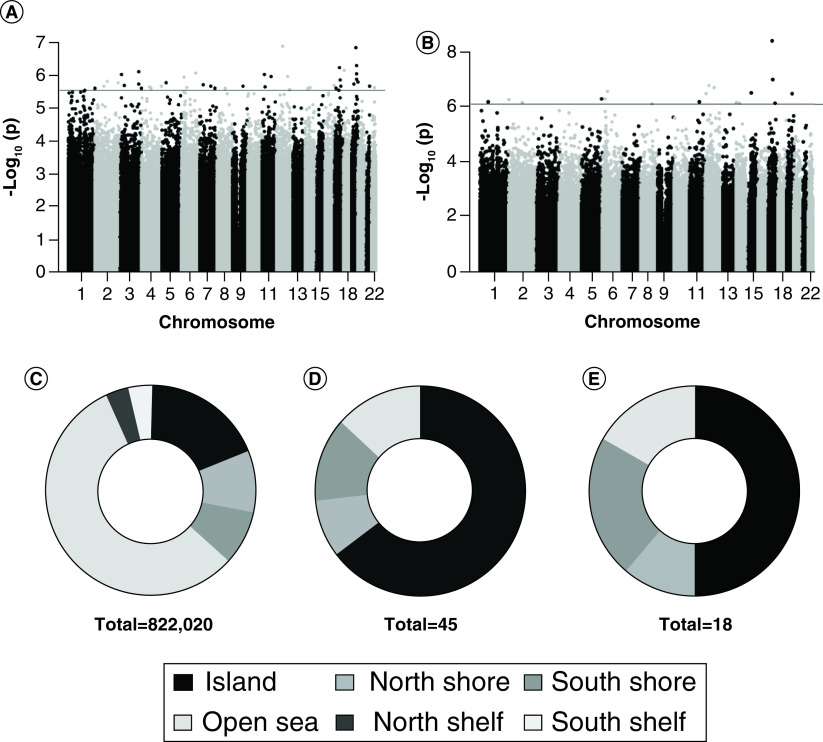

In M3, the LysoPC-sat was associated with 45 differentially methylated CpG sites (Figure 1A) and LysoPE-sat was associated with 18 differentially methylated CpG sites (Figure 1B). In comparison with the distribution of CpG sites in the EPIC bead array (Figure 1C), more of the CpG sites associated with LysoPC-sat (Figure 1D) and LysoPE-sat (Figure 1E) were located within CpG islands and shores and had increased DNA methylation. There was overlap in the CpG sites associated with M3 LysoPC-sat and LysoPE-sat including increased methylation at CpG sites annotated to SLFN5 (probe ID cg23010414), HIST1H1D (probe ID cg15485323) and DBI (probe ID cg02325290) (Table 4). Increased methylation was observed in the CpG island of DBI (Supplementary Figure 2); a highly conserved gene that binds medium- and long-chain acyl-Coenzyme A esters and plays a role in lipid metabolism [36].

Figure 1. . Maternal term saturated lysophospholipids are associated with differential DNA methylation in promoter regions of infant cord blood leukocyte genes.

Differentially methylated CpG sites were classified fitting linear models using empirical Bayes methodology. Models were adjusted for sex, EPIC bead array sample plate, nRBC and B cells. Represented by Manhattan plot, (A) 45 CpG sites were significantly related to maternal term (M3) lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPE)-saturated (sat) (false discovery rate [FDR] <0.05) and (B) 18 CpG probes were significantly related to M3 LysoPE-sat (FDR <0.05). Line signifies the -log(p-value) corresponding to the FDR <0.05. Differentially methylated CpG sites were classified by genomic location. (C) Percentage of CpG sites within a CpG island, shore, shelf and open sea in the EPIC bead array. Percentage of statistically significant CpG sites within a CpG island, shore, shelf and open sea reported for association with (D) M3 LysoPC-sat and (E) M3 LysoPE-sat.

M3 LysoPC-sat was associated with differential methylation in a variety of other genes related to metabolism and development (Table 4) including in a CpG island of ATP5G1 (logFC = 0.28, probe ID cg14103143), which encodes a subunit of mitochondrial ATP synthase; the south shore of COQ5 (logFC = 0.17, probe ID cg11075121), a mitochondrial gene that catalyzes the methylation in the COQ10 synthetic pathways [37]; a CpG island of GABBR2 (logFC = 0.25, probe ID cg11509404), which plays a role in coupling to G-proteins [38] and stimulates phospholipase A2, an enzyme that hydrolyzes phospholipids releasing the sn-2 FA; and a CpG island of PA2G4 (logFC = 0.29, probe ID cg21001214), a gene encoding an RNA binding protein involved in growth regulation.

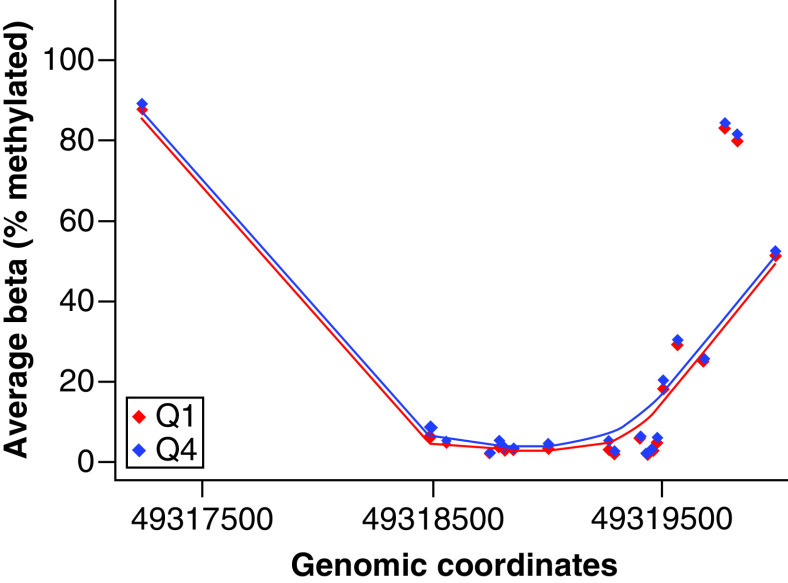

DMRs including multiple CpG sites are reported in Table 5. In the DMR analysis, M3 LysoPE-sat was associated with increased methylation across 13 CpG sites within a CpG island of FKBP11 (mean β fold change = 0.0064, Stouffer p = 0.00047) (Table 5). Percent methylation differences between quartile 1 (Q1) and quartile 4 (Q4) M3 LysoPE-sat exposure are represented in Figure 2. No additional statistically significant DMRs by maternal lipid groups were observed.

Table 5. . Classification of differentially methylated regions in umbilical cord blood leukocytes associated with maternal lipid groups.

| Time point | Lipid group | Chromosome coordinates | Number of CpGs | βmean FC | βmax FC | Stouffer p-value | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3 | LysoPE sat M3 | chr12:49318740-49319500 | 13 | 0.0064 | 0.0174 | 0.0005 | FKBP11 |

Directionality indicated by βmax and βmean FC. Significance denoted by a Stouffer p-value < 0.05. Chromosome coordinates, number of CpG sites in the region, and annotated gene are reported.

FC: Fold change; LysoPE: Lysophosphatidylethanolamine; M3: Maternal term; sat: Saturated.

Figure 2. . Percent methylation within CpG sites in FKBP11 associated with maternal term saturated lysophosphatidylethanolamine.

The average β-value for each CpG site in FKBP11 across subjects in Q1 and Q4 of maternal term lysophosphatidylethanolamine-saturated.

Pathway analysis of differentially methylated genes

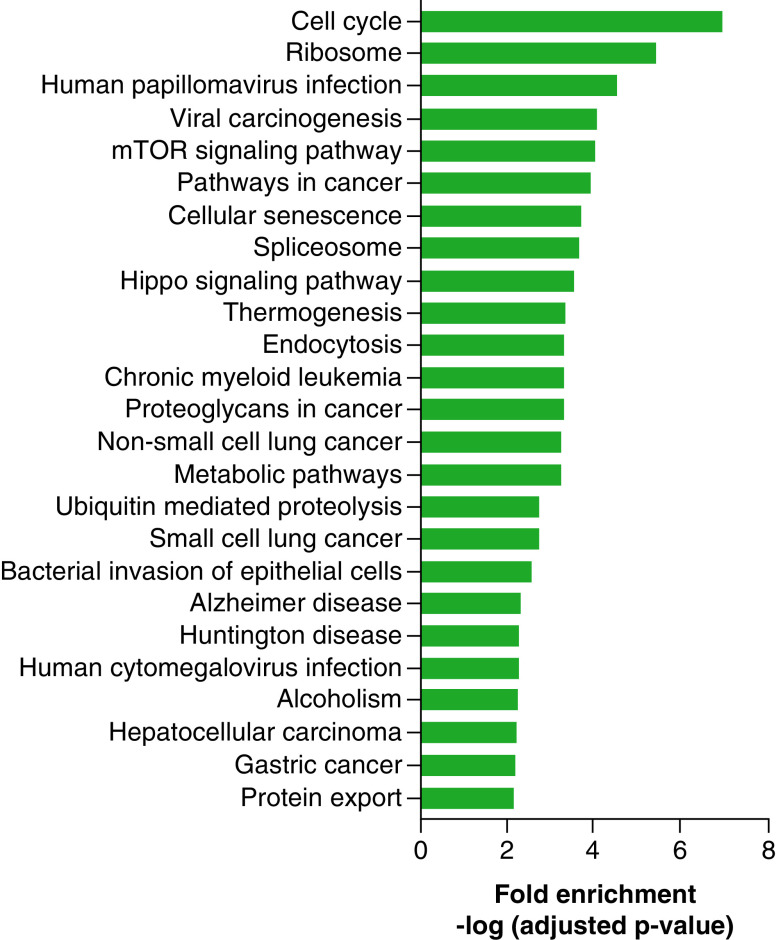

To further investigate the biological relevance of the results, pathway analysis was used to classify enrichment of KEGG biological pathways in genes with differential methylation. Lipid groups selected for pathway analysis included M3 LysoPC-sat and M3 LysoPE-sat. The only lipid group with significantly enriched KEGG pathways was M3 LysoPC-sat (Supplementary Table 2). Figure 3 reports the top 25 significantly enriched biological pathways associated with M3 LysoPC-sat. Multiple enriched KEGG pathways are related to cell proliferation including cell cycle, ribosome, human papillomavirus infection, viral carcinogenesis, mTOR signaling pathway and pathways in cancer.

Figure 3. . Top 25 significantly enriched KEGG biological pathways associated with maternal term (M3) LysoPC-sat.

Enriched biological pathways were classified by selected differentially methylated sites (false discovery rate <0.1) associated with maternal term lysophosphatidylcholine-saturated for pathway analysis. Biological pathways were identified from the KEGG database. Fold enrichment values were computed using the -log adjusted p-value.

Q1: Quartile 1; Q4: Quartile 4.

Discussion

In this study using 100 mother-infant dyads from the MMIP cohort, we classified the relationship between the maternal lipidome at early gestation and delivery with DNA methylation profiles in CB leukocytes. Measurement of the maternal lipidome twice during gestation allowed us to assess how lipid exposure may influence the infant epigenome based on the stage of fetal development. Our results indicate that specific lipid groups at the end of pregnancy (M3) are associated with differential umbilical CB DNA methylation. In particular, M3 LysoPLs with saturated FA tails are associated with increased CB DNA methylation, especially within CpG islands and shores.

Within the 41 lipid groups, M3 LysoPC-sat and LysoPE-sat were the main maternal lipid groups related to differential methylation in CB leukocytes. Most differentially methylated CpG sites associated with this lipid fraction were within CpG islands and shores, increasing the potential relevance to programming infant gene expression [39]. Both LysoPC-sat and LysoPE-sat were associated with changes in methylation of genes related to lipid metabolism, including increased methylation within a CpG island of DBI, the medium- and long-chain acyl-CoA ester binding protein [36]. Long-chain fatty acyl-CoAs are highly expressed in tissues with active lipid metabolism, such as the liver and adipose tissue [40]. DBI plays a role in a variety of cellular functions [41] and in the esterification of long-chain FA into triglycerides and phospholipids [42] as well as FA oxidation [43].

Our results indicate that M3 LysoPLs with saturated FA tails are associated with multiple markers of umbilical CB cell growth. In the DMR analysis, higher M3 LysoPE-sat was associated with increased DNA methylation across 13 CpG sites within a CpG island of FKBP11, a gene belonging to a family of FK506 binding proteins. It has been suggested that FK506 binding proteins play a role in the regulation of mTOR, a master regulator of cell growth [44]. The FKBPs-rapamycin complex binds to mTOR and prevents the binding of mTOR substrates [44]. A recent study has demonstrated that the FKBP11 encoded protein, FK506-binding protein 11, mediates the stimulatory effect of XBP1 on the mTOR, leading to cell growth [45]. In the biological pathway analysis, cell proliferation, ribosomal metabolism/translation pathways and mTOR signaling pathways were enriched among differentially methylated genes by M3 LysoPC-sat (Figure 3).

In line with enrichment of differentially methylated loci for pathways and functions related to cell proliferation and/or growth, our previous study identified that LysoPC and LysoPE are selectively depleted in maternal plasma at M3 and elevated in infant CB; CB LysoPLs are also positively associated with birth weight [8]. Our results are confirmed by other studies demonstrating CB LysoPCs with varying chain length and saturation are positively associated with newborn birth weight [46–48], as well as with weight at age 6 months [46].

It has been suggested that maternal LysoPLs may influence the infant epigenome via the transport of choline to tissues [17]. Choline is shuttled into a variety of pathways including acetylcholine synthesis, the production of phosphatidylcholine and the production of betaine. Betaine is a source of methyl groups for the synthesis of methionine, the precursor to the principal methyl-group donor, S-adenosylmethioine, needed for de novo and maintenance DNA methylation. During pregnancy, the dynamics of choline metabolism shifts to increase production of phosphatidylcholine via the Kennedy pathway and the phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase pathway [49]. Therefore, alterations in the levels of maternal LysoPLs may alter the input of choline into the one carbon metabolism pathway, potentially influencing DNA methylation establishment and maintenance in rapidly dividing cells of the offspring. While LysoPLs, in particular LysoPC, may contribute to methyl group donation for one-carbon metabolism, it is unknown why and how differential methylation is occurring in specific genes associated with cell proliferation. It is possible that changes occurred throughout the genome, but these studies were not statistically powered to identify all changes. Thus, the impact of mid- and late-gestation LysoPLs on epigenetic programming in larger birth cohorts and multiple tissue types merits further investigation.

The majority of differentially methylated CpG sites were associated with the M3 lipidome, however a few M1 lipid groups were associated with CpG site methylation. Early gestation M1 PG-mono was positively associated with a CpG site in the open sea of PPARGC1B. PPAR and PGC1 gene families have been previously associated with type 2 diabetes risk [50]. In addition, the methylation of the PPARGC1B locus in peripheral blood cells in adults (ages 55–80 years) was found to be inversely associated to adherence to a Mediterranean diet [51], which in turn is associated with higher monounsaturated and lower polyunsaturated phospholipid levels [52–54]. M1 LysoPC-sat was associated with increased methylation in a CpG site located in a CpG shore of MPP5. MPP5 is a palmitoylated protein coding gene, which is a scaffolding protein in the outer membrane of retinal glial cells [55]. MPP5 was found to be up-regulated in placenta villus cells of women with intrauterine growth retardation and severe preeclampsia [56].

A recently published study using the CHAMACOS cohort measured 92 lipids at approximately 26 weeks gestation and assessed the relationship between the maternal metabolome and DNA methylation in infant CB using the Infinium 450K Bead Chip [17]. Their targeted metabolomics platform consisted of diglyceride, phosphatidic acid, LysoPL, monoglyceride, phospholipid, sphingolipid and triglyceride lipid classes mainly composed of FA tails that are 16:0, 18:0, 18:1 or 20:4. They observed multiple lipids in maternal plasma were associated with infant DNA methylation including four phospholipids and four LysoPLs. There is no overlap between the statistically significant CpG sites or related genes identified between our two analyses, potentially due to differences in the maternal metabolome measurement time, the DNA methylation array, and limited statistical power to detect all true associations. In biological pathway analysis, the CHAMACOS cohort found significant differentially methylated genes were involved in biological pathways such as Huntington's disease, pyruvate metabolism, and Parkinson's disease. Both Huntington's disease and Parkinson's disease were significantly enriched pathways associated with M3 LysoPC-sat in our analysis (Figure 3 & Supplementary Table 2). In the MMIP cohort, M3 LysoPC-sat is associated with increased methylation in a CpG island of the gene ATP5G1, which is a gene related to the pathogenesis of Huntington's disease and Parkinson's disease. Together, results from MMIP and CHAMACOS emphasize the importance of the maternal LysoPL fraction in establishing the infant epigenome during mid-gestation to late gestation.

Previous analyses using a subset of the MMIP study [16] employed a targeted approach to identify metabolite-DNA methylation associations in genes related to lipid metabolism and growth. The targeted metabolomics assay used profiled amino acids, free FAs, and acylcarnitines. Out of 76 metabolites measured in first trimester and at term, maternal very long-chain FAs and acylcarnitines were the most consistently associated with offspring DNA methylation. Use of different metabolite extraction techniques and an epigenome-wide approach may have contributed to the lack of overlap between our two studies. Future directions for the MMIP cohort include profiling the untargeted metabolome, including amino acids, free FAs, acylcarnitines and one carbon metabolism metabolites to determine its association with infant CB epigenome-wide DNA methylation. Combining the previous targeted approach and current ‘omics’ approach in the MMIP cohort provides evidence for the influence of maternal lipids and related metabolites in early and late gestation on CB DNA methylation. Finally, to test the hypotheses generated from this study, interventions, such as maternal dietary change or pre conception weight loss, could be used to change the metabolome in a consistent way followed by evaluation of DNA methylation of specific sites. In addition, with larger numbers of subjects, we should be able to determine whether there is a sex-specific relationship between the maternal metabolome and DNA methylation.

Conclusion

Our findings provide support that the maternal metabolic environment during gestation, in particular LysoPLs, influences the umbilical CB epigenome, potentially regulating gene expression. A novelty of this analysis was the incorporation of two ‘omics' platforms; an untargeted lipidomics platform with measurements across gestation and the EPIC Bead Array. Multiple maternal measures across gestation determine how maternal lipids influence fetal programming during different periods of gestation. We acknowledge that maternal delivery plasma may not be a true reflection of late gestation lipids due to the stress of parturition. Maternal samples in this analysis were not fasted, presenting challenges in interpreting these results. At last, we acknowledge that CB leukocyte methylation may not be the only contributor for risk of cardiometabolic disease and additional epigenetic processes such as histone modifications may also be relevant.

Future perspective

Profiling the metabolome and lipidome provides a deeper classification of the maternal metabolic environment to which the developing fetus is exposed. Utilizing these techniques in the clinical setting may potentially classify differences in the maternal metabolome that can be modulated prior to pregnancy to optimize gestational health. Epigenetic marks in easily accessible cells and tissues, such as umbilical CB leukocytes, may help clinicians classify health risk in offspring. Understanding these risks can allow for monitoring of the offspring’s growth trajectory and potential interventions to prevent adult cardiometabolic disease.

Summary points.

The maternal metabolic environment may influence DNA methylation levels in the developing fetus, with potential long-term health consequences in the offspring via epigenetic programming.

The maternal plasma lipidome was profiled across gestation during the first trimester and at delivery, including a variety of lipid classes.

DNA methylation was quantified using the Infinium MethylationEPIC bead array at approximately 850,000 CpG sites, containing probes that hybridize to loci throughout the genome located within CpG islands, genes, transcription binding sites, open chromatin regions and more.

Lipid groups in maternal plasma at delivery were associated with differential DNA methylation, potentially suggesting the importance of maternal lipid levels during late gestation.

Maternal delivery saturated lysophospholipids, including lysophosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylethanolamine, were associated with increased DNA methylation at over 60 CpG sites.

Many of the differentially methylated CpG sites associated with maternal delivery saturated lysophospholipids were localized in CpG islands.

Biological pathways pertaining to differentially methylated CpG sites associated with maternal delivery saturated lysophosphatidylcholine were involved in cell proliferation and growth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the members of the Michigan Regional Comprehensive Metabolomics Resource Core, T Soni and TM Rajendiran, for their assistance in the processing of the lipidomics data. We would like to acknowledge M Puttabyatappa, S Milewski and S Rogers for help with recruitment and processing of samples.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.futuremedicine.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/epi-2020-0234

Financial & competing interests disclosure

University of Michigan NIEHS/EPA Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Center P01 ES022844/RD 83543601 (V Padmanabhan, DC Dolinoy, PXK Song and JM Goodrich), the Michigan Regional Comprehensive Metabolomics Resource Core (MRC2) U24 DK097153 (CF Burant); NIH Children’s Health Exposure Analysis Resource (CHEAR), 1U2C ES026553 (DC Dolinoy, JM Goodrich and CF Burant), Michigan Lifestage Environmental Exposures and Disease (M-LEEaD) NIEHS Core Center P30 ES017885 (V Padmanabhan, DC Dolinoy, JM Goodrich, PXK Song and CF Burant), NIH/NIEHS UG3 OD023285 (V Padmanabhan and DC Dolinoy), Molecular Phenotyping Core, Michigan Nutrition and Obesity Center P30 DK089503 (CF Burant and DC Dolinoy) and Michigan Regional Metabolomics Resource Core R24 DK097153 (CF Burant), and The A. Alfred Taubman Research Institute (CF Burant). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Data sharing statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request. Metabolomics data is available at the National Metabolomics Data Repository (metabolomicsworkbench.org/data/index.php).

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Barker DJP The origins of the developmental origins theory. J. Intern. Med. 261(5), 412–417 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindsay KL, Hellmuth C, Uhl O et al. Longitudinal metabolomic profiling of amino acids and lipids across healthy pregnancy. PLoS ONE 10(12), e0145794 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellmuth C, Lindsay KL, Uhl O et al. Association of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI with metabolomic profile across gestation. Int. J. Obes. 41(1), 159–169 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandler V, Reisetter AC, Bain JR et al. Associations of maternal BMI and insulin resistance with the maternal metabolome and newborn outcomes. Diabetologia 60, 518–530 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desert R, Canlet C, Costet N, Cordier S, Bonvallot N Impact of maternal obesity on the metabolic profiles of pregnant women and their offspring at birth. Metabolomics 11(6), 1896–1907 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maitre L, Villanueva CM, Lewis MR et al. Maternal urinary metabolic signatures of fetal growth and associated clinical and environmental factors in the INMA study. BMC Med. 14(177), 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenseke B, Prater MR, Bahamonde J, Gutierrez JC Current thoughts on maternal nutrition and fetal programming of the metabolic syndrome. J. Pregnancy 2013(368461), 1–13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaBarre JL, Puttabyatappa M, Song PX et al. Maternal lipid levels across pregnancy impact the umbilical cord blood lipidome and infant birth weight. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 14209 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Analysis describes the changes in the lipidome across gestation and the association between lipid groups and birth weight in MMIP participants that were included in this current study.

- 9.Pettitt DJ, Jovanovic L Birth weight as a predictor of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the U-shaped curve. Curr. Diab. Rep. 1, 78–81 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barker DJP, Eriksson JG, Forsén T, Osmond C Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 31(6), 1235–1239 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gluckman P, Hanson M, Cooper C, Thornburg KL Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 359(1), 61–73 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu J, Stevens M, Xing X et al. Mapping of variable DNA methylation across multiple cell types defines a dynamic regulatory landscape of the human genome. G3 6(4), 973–986 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James P, Sajjadi S, Tomar AS et al. Candidate genes linking maternal nutrient exposure to offspring health via DNA methylation: a review of existing evidence in humans with specific focus on one-carbon metabolism. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47(6), 1910–1937 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharp GC, Lawlor DA, Richmond RC et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain, offspring DNA methylation and later offspring adiposity: findings from the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44(4), 1288–1304 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engel SM, Joubert BR, Wu MC et al. Neonatal genome-wide methylation patterns in relation to birth weight in the Norwegian mother and child cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 179(7), 834–842 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchlewicz EH, Dolinoy DC, Tang L et al. Lipid metabolism is associated with developmental epigenetic programming. Sci. Rep. 6(34857), 1–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Relationship between the targeted metabolome, in particular amino acids, fatty acids and acylcarnitines, and DNA methylation in genes associated with growth from a subset of MMIP participants.

- 17.Tindula G, Lee D, Huen K, Bradman A, Eskenazi B, Holland N Pregnancy lipidomic profiles and DNA methylation in newborns from the CHAMACOS cohort. Environ. Epigenetics 5(1), 1–11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• The first manuscript describes the relationship between the lipidome during mid-gestation and DNA methylation using a 450K array in the newborn.

- 18.Kelley AS, Banker M, Goodrich JM et al. Early pregnancy exposure to endocrine disrupting chemical mixtures are associated with inflammatory changes in maternal and neonatal circulation. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 1–14 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puttabyatappa M, Banker M, Zeng L et al. Maternal exposure to environmental disruptors and sexually dimorphic changes in maternal and neonatal oxidative stress. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105(2), 492–505 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veiga-Lopez A, Kannan K, Liao C, Ye W, Domino SE, Padmanabhan V Gender-specific effects on gestational length and birth weight by early pregnancy BPA exposure. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100(11), E1394–E1403 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afshinnia F, Rajendiran TM, Karnovsky A et al. Lipidomic signature of progression of chronic kidney disease in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort. Kidney Int. Rep. 1(4), 256–268 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Description of the untargeted shotgun lipidomics methodology.

- 22.Gika HG, Macpherson E, Theodoridis GA, Wilson ID Evaluation of the repeatability of ultra-performance liquid chromatography-TOF-MS for global metabolic profiling of human urine samples. J. Chromatogr. B 871, 299–305 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kind T, Liu K, Lee DY, Defelice B, Meissen JK, Fiehn O LipidBlast in silico tandem mass spectrometry database for lipid identification. Nat. Methods 10(8), 755–758 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakulski KM, Feinberg JI, Andrews SV et al. DNA methylation of cord blood cell types: applications for mixed cell birth studies. Epigenetics 11(5), 354–362 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics 30(10), 1363–1369 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feber A, Guilhamon P, Lechner M et al. Using high-density DNA methylation arrays to profile copy number alterations. Genome Biol. 15(2), 1–13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortin J, Labbe A, Lemire M et al. Functional normalization of 450k methylation array data improves replication in large cancer studies. Genome Biol. 15(503), 1–17 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du P, Zhang X, Huang C et al. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 11(587), 1–9 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh J, Mainigi M, Coutifaris C, Sapienza C Outlier DNA methylation levels as an indicator of environmental exposure and risk of undesirable birth outcome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25(1), 123–129 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43(7), e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teschendorff AE, Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A et al. An epigenetic signature in peripheral blood predicts active ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE 4(12), e8274 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57(1), 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geeleher P, Hartnett L, Egan LJ, Golden A, Raja Ali RA, Seoighe C Gene-set analysis is severely biased when applied to genome-wide methylation data. Bioinformatics 29(15), 1851–1857 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phipson B, Maksimovic J, Oshlack A missMethyl: an R package for analyzing data from Illumina's HumanMethylation450 platform. Bioinformatics 32(2), 286–288 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Data analysis pipeline including the method used to identify biological pathways enriched with significant CpG sites.

- 35.Kanehisa M, Goto S KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neess D, Bek S, Engelsby H, Gallego SF, Færgeman NJ Long-chain acyl-CoA esters in metabolism and signaling: role of acyl-CoA binding proteins. Prog. Lipid Res. 59, 1–25 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malicdan MCV, Vilboux T, Ben-Zeev B et al. A novel inborn error of the coenzyme Q10 biosynthesis pathway: cerebellar ataxia and static encephalomyopathy due to COQ5 C-methyltransferase deficiency. Hum. Mutat. 39(1), 69–79 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nomura R, Suzuki Y, Kakizuka A, Jingami H Direct detection of the interaction between recombinant soluble extracellular regions in the heterodimeric metabotropic gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 283(8), 4665–4673 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du X, Han L, Guo AY, Zhao Z Features of methylation and gene expression in the promoter-associated CpG islands using human methylome data. Comp. Funct. Genomics. 2012, 598987 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Færgeman NJ, Wadum M, Feddersen S, Burton M, Kragelund BB, Knudsen J Acyl-CoA binding proteins; structural and functional conservation over 2000 MYA. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 299, 55–65 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Færgeman NJ, Knudsen J Role of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA esters in the regulation of metabolism and in cell signalling. Biochem. J. 323, 1–12 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang H, Atshaves BP, Frolov A, Kier AB, Schroeder F Acyl-coenzyme A binding protein expression alters liver fatty acyl-coenzyme A metabolism. Biochemistry 44, 10282–10297 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris FT, Rahman SMJ, Hassanein M et al. Acyl-coenzyme A-binding protein regulates Beta-oxidation required for growth and survival of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 7(7), 748–758 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hausch F, Kozany C, Theodoropoulou M, Fabian A FKBPs and the Akt/mTOR pathway. Cell Cycle 12(15), 2366–2370 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Deng Y, Zhang G et al. Spliced X-box binding protein 1 stimulates adaptive growth through activation of mTOR. Circulation 140(7), 566–579 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel N, Hellmuth C, Uhl O et al. Cord metabolic profiles in obese pregnant women; insights into offspring growth and body composition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 103(1), 346–355 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hellmuth C, Uhl O, Standl M et al. Cord blood metabolome is highly associated with birth weight, but less predictive for later weight development. Eur. J. Obes. 10, 85–100 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu Y-P, Reichetzeder C, Prehn C et al. Cord blood lysophosphatidylcholine 16:1 is positively associated with birth weight. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 45(2), 614–624 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan J, Jiang X, West AA et al. Pregnancy alters choline dynamics: results of a randomized trial using stable isotope methodology in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98(6), 1459–1467 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villegas R, Williams SM, Gao YT et al. Genetic variation in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1 (PGC1) gene families and type 2 diabetes. Ann. Hum. Genet. 78(1), 23–32 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arpón A, Riezu-Boj J, Milagro F et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet is associated with methylation changes in inflammation-related genes in peripheral blood cells. J. Physiol. Biochem. 73, 445–455 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bondia-Pons I, Martinez JA, de la Iglesia R et al. Effects of short- and long-term Mediterranean-based dietary treatment on plasma LC-QTOF/MS metabolic profiling of subjects with metabolic syndrome features: The Metabolic Syndrome Reduction in Navarra (RESMENA) randomized controlled trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 59, 711–728 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toledo E, Wang DD, Ruiz-Canela M et al. Plasma lipidomic profiles and cardiovascular events in a randomized intervention trial with the Mediterranean diet. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 106(3), 973–983 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tong TYN, Koulman A, Griffin JL, Wareham NJ, Forouhi NG, Imamura F A combination of metabolites predicts adherence to the Mediterranean diet pattern and its associations with insulin sensitivity and lipid homeostasis in the general population: the Fenland Study, United Kingdom. J. Nutr. 150(3), 568–578 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Rossum AG, Aartsen WM, Meuleman J et al. Pals1/Mpp5 is required for correct localization of Crb1 at the subapical region in polarized Muller glia cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15(18), 2659–2672 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nevalainen J, Skarp S, Savolainen E-R, Ryynanen M, Jarvenpaa J Intrauterine growth restriction and placental gene expression in severe preeclampsia, comparing early-onset and late-onset forms. J. Perinat. Med. 45(7), 869–877 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.